Mandibular fractures in edentulous patients represent a difficult situation to solve. Atrophy is progressively caused by resorption of alveolar bone consequent to teeth loss [

1], and the use of dentures in these patients accelerates mandibular atrophy [

2,

3]. Fragment reduction and fracture consolidation are difficult, due to bone atrophy, diminished capacity of bone regeneration, and the lack of anatomic landmarks to guide the alignment of fragments. Therefore, poor union or asymmetry may be observed. As a matter of fact, the selection of the correct type of osteosynthesis is essential to achieve fracture stability. We present a case series of patients with edentulous mandibular fractures, treated with open reduction and rigid internal fixation (RIF) following AO principle of load-bearing osteosynthesis.

Material and Methods

A retrospective observational study was performed, including all the edentulous patients with mandibular fracture diagnosis who received surgical treatment at the Head and Neck Section of the General Surgery Department of Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, from November 1991 to July 2011. Preoperatively, after clinical evaluation, all the patients were studied with computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast, with axial and coronal projections, usually accompanied by panoramic radiography. Most recent cases were studied with multislice CT scan, thus providing tridimensional reconstruction.

The following information was collected from the patient’s medical records: age, gender, and etiology of the fracture. According to the location of the fracture in the mandible, they were classified as symphysis, body, angle, ascending ramus, and condyle. The existence of comminution, compound fracture, infection, and the period of time between injury and fixation were also searched. For each of the fractures, the type of surgical approach employed (intraoral or extraoral), type of osteosynthesis material used for fixation, use of bone grafts, drains, postoperative complications observed, and need of reoperation were registered. As well, the number of reoperations for osteosynthesis removal was sought.

The whole population of patients received broad-spectrum antibiotics during hospitalization. Postoperatively, fracture reduction was confirmed using panoramic radiographs and CT scan (in selected patients). Fracture reduction was considered as satisfactory when the fragments were correctly aligned on radiographs. All patients were followed up for at least 6 months.

Patients with edentulous mandible fractures who were treated with other method of fixation were not included in the present study. The obtained data from our charts were submitted to descriptive statistical analysis for the purpose of this article. Because of the retrospective nature of this study, it was granted an exemption in writing by the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires Institutional Review Board.

Results

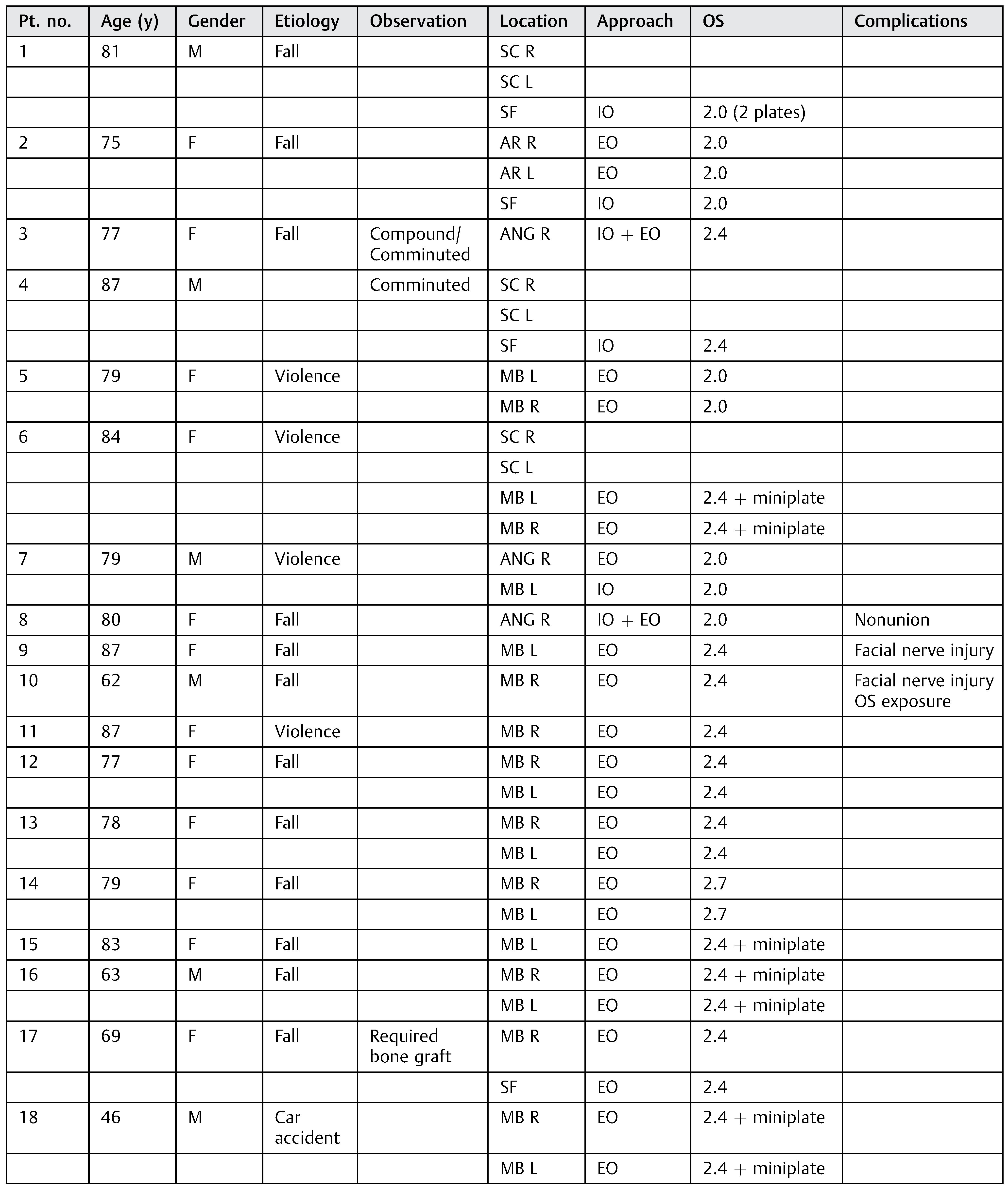

Eighteen edentulous patients with mandibular fracture diagnosis were surgically treated at the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires between November 1991 and July 2011. The mean age of the population was 76.2 years old (range, 46–87), and divided into 12 female (66.6%) and 6 male (33.3%) patients. The fractures were mainly caused by falls from their own height (13 patients, 72.2%). The rest of the traumatisms were caused by violence (4 patients, 22.2%) and motor vehicle accident (1 patient, 5.5%). The 18 patients showed 35 fracture lines in total. The most common site of fracture was the mandibular body (20; 57.1%), 7 of which were bilateral. Six fractures were located condylar or sub-condylar (17.1%), 4 were symphyseal or parasymphyseal (11.4%), 3 were angular (8.6%), and 2 were located in the ascending ramus (5.7%). The only fractures that were conservatively treated were those six located in the condyle. The rest of the fractures (29) were treated with open reduction and RIF. Only one compound fracture was observed in our series, presented in a patient with a mandibular body fracture caused by a fall from her own height (

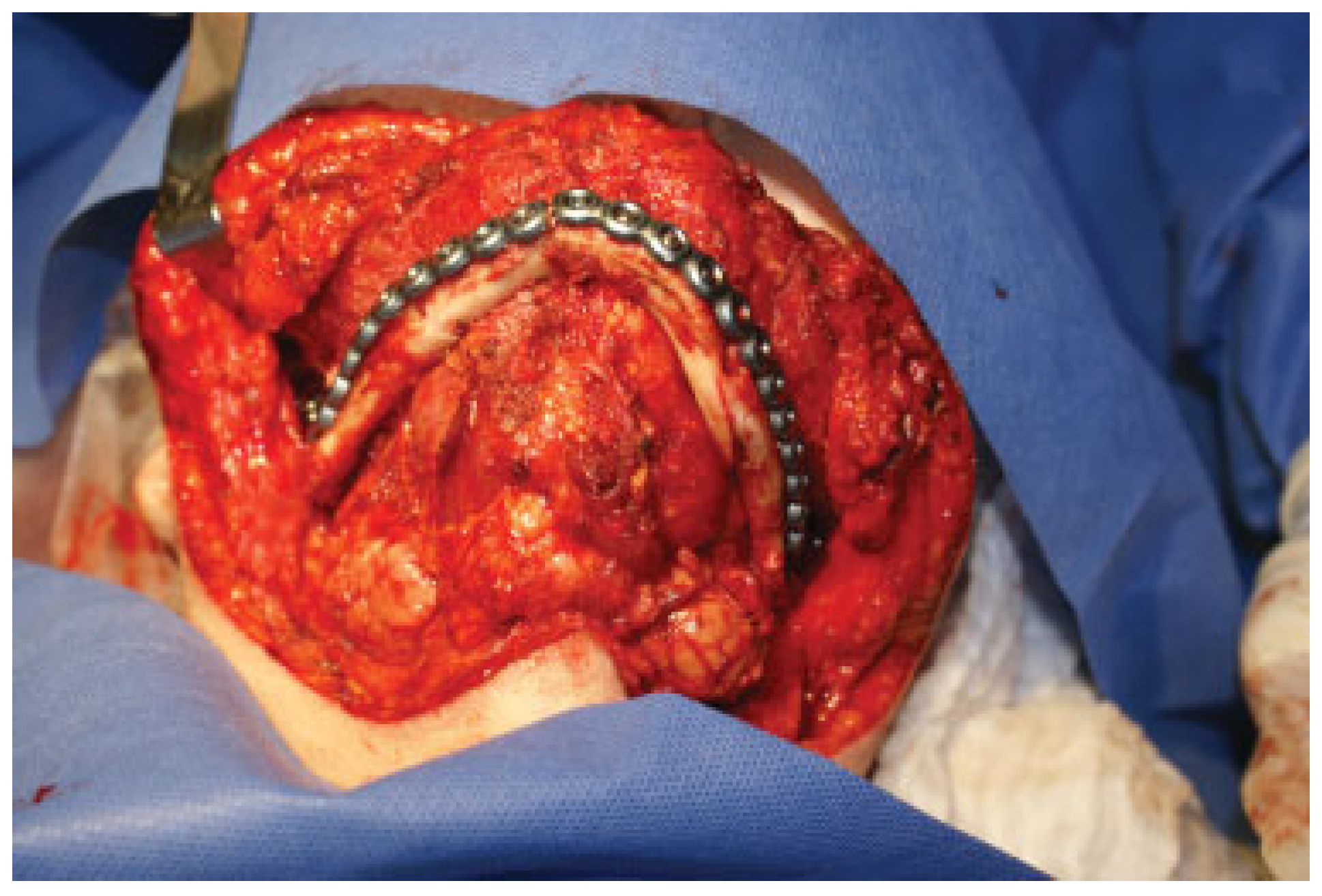

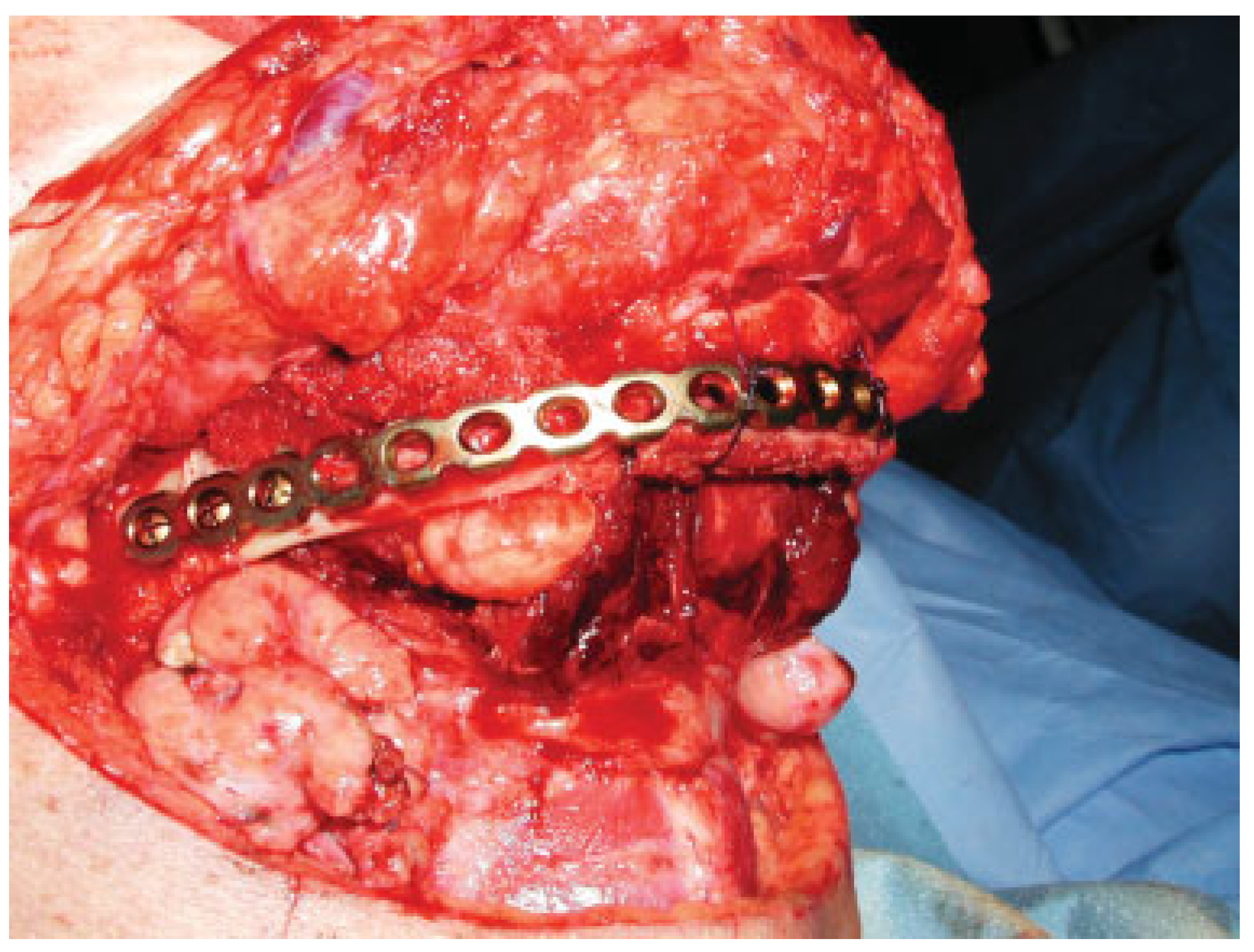

Table 1). The mean time registered between the traumatic event and fracture reduction was 67.8 hours. Most of the fractures were approached extraorally (23; 79.3%) (

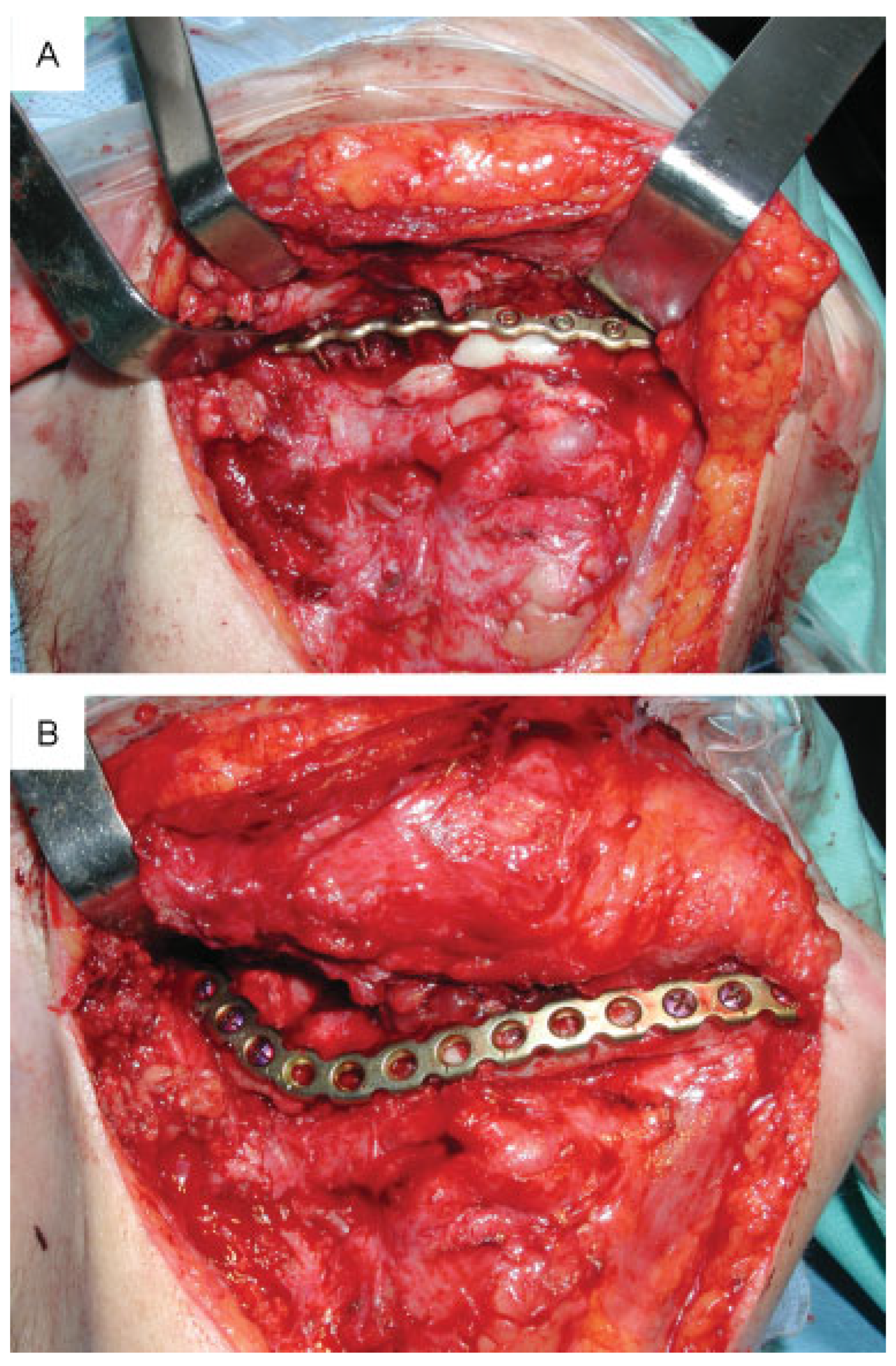

Figure 1), while three symphyseal fractures and one of the mandibular body fractures (13.8%) were solved by an exclusively intraoral approach. Two patients with angular fractures were reduced using a combined intraoral and extraoral approach; one of these is the patient with the compound fracture previously mentioned, on whom we took advantage of the skin wound for extraoral access. In all the patients, the osteosynthesis material selected for RIF was strong enough to carry out the AO principle of load-bearing osteosynthesis. The reduced fractures were mainly fixated with large 2.4-mm reconstruction plates with locking system, in 18 cases (62%); 7 of these were previously fixated with miniplates in the inferior mandibular border to maintain the reduction during the larger plate fixation. Nine fractures (39%) were fixated with 2.0-mm locking system plates, and finally two of the patients of our population were treated with 2.7-mm reconstruction plates. Suction drains were systematically used in extraoral wounds, and removed on the following day. On late followup, fracture reduction and stabilization was considered as satisfactory in 96.5%. There was one case of unstable fracture in a patient with an angular fracture treated with a 2.0-mm locking plate fixated with three screws per side. As a matter of fact, the patient required a reoperation, where the osteosynthesis plated was removed and replaced with a larger 2.4-mm reconstruction locking plate (

Figure 2). Another reoperation was required in a patient with a mandibular body fracture fixed with a reconstruction plate, on whom osteosynthesis material was exposed on its mental end, 15 months after the primary surgery.

This complication was considered to be due to insufficient plate bending on the plate’s medial end. Therefore, this end of the plate was sectioned and removed using the exposition site for surgical access. Temporal palsy of the marginal ramus of the facial nerve was found in two patients.

Summarizing, in an 18-patient population the complication rate was 22.2% and the reoperation rate was 11.1%. In addition, only one patient required a reoperation due to unstable fracture.

Discussion

Most of the articles in literature that investigate edentulous mandibular fractures present short series of patients due to its low incidence. The lack of randomized controlled trials explains the scarcity of reliable recommendation related to the treatment of this type of fracture [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Despite the fact that edentulism’s rate tends to decrease worldwide, the increase in life expectancy implies an older population who show accentuated mandibular atrophy [

8]. In Argentina, there is no register of edentulism rate; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States reports for the period between 2008 and 2010 a 7.8% edentulism rate in American population > 18 years, while in patients > 85 years, the rate increases to 33.1%. Moreover, the prevalence of edentulism in poor American citizens is 13.8% in individuals > 18 years and 52.5% in individuals > 85 years [

9]. Mandibular atrophy tends to be critical in the mandibular body; our series showed this localization as the most common site of fracture. Luhr et al. [

10] created the mandibular atrophy classification used nowadays, according to mandibular height: Class I, 16 to 20 mm; Class II, 11 to 15 mm; Class III, < 10 mm. It has been proven that complications related to fracture consolidation are higher in patients with greater decrease in mandibular height [

11]. One of the factors that supports this is the reduced cross section and smaller contact area of fractured ends in atrophic bone. Furthermore, bone quality is diminished, it may be sclerotic, and suffers blood flow decrease [

1].

Surgical treatment under general anesthesia is often conditioned by the poor general condition of an ancient patient. Consequently, it is mandatory to correctly decide the treatment from the beginning. At present, advances in trauma management and elder patient anesthesia have reduced the surgical risk for this population [

5]. Indeed, we have not observed complications related to anesthesia in our series. As most of the edentulous patient’s biological and biomechanical conditions cannot be modified, the most important issue that will affect the fracture’s prognosis is the type of osteosynthesis plate used for fixation.

Despite some authors recommend miniplates for edentulous mandibular fractures [

12,

13], nowadays most of maxillofacial surgeons prefer stronger plates for fixation [

14,

15]. Some studies report many complications related with the use of reconstruction plates, seldom requiring osteosynthesis material removal [

16]. Moreover, some authors describe a higher rate of wound dehiscence due to fixation with large plates [

17]. These two items have not been observed as a major concern in our series. One of the largest series of edentulous mandibular fractures found in literature, described by Bruce and Ellis, concluded that the optimal treatment for this kind of fractures is open reduction accompanied by stable fixation with large osteosynthesis plates [

6]. Periosteum removal in order to place the osteosynthesis material seems not to be a problem as far as the plate is strong enough to support mandibular biomechanical forces. However, when periosteum is detached, it is performed on the vestibular cortical bone only, without injuring the lingual periosteum. Interestingly, edentulous mandibles have the advantage that they do not require a strict anatomical alignment of the fractures fragments. Dentures can compensate irregularities on fragment alignment and mandibular surface [

6]. The fact that there is no need to preserve a dental occlusion in an edentulous patient probably explains why most of condylar fractures do not require surgical treatment, as observed in our series.

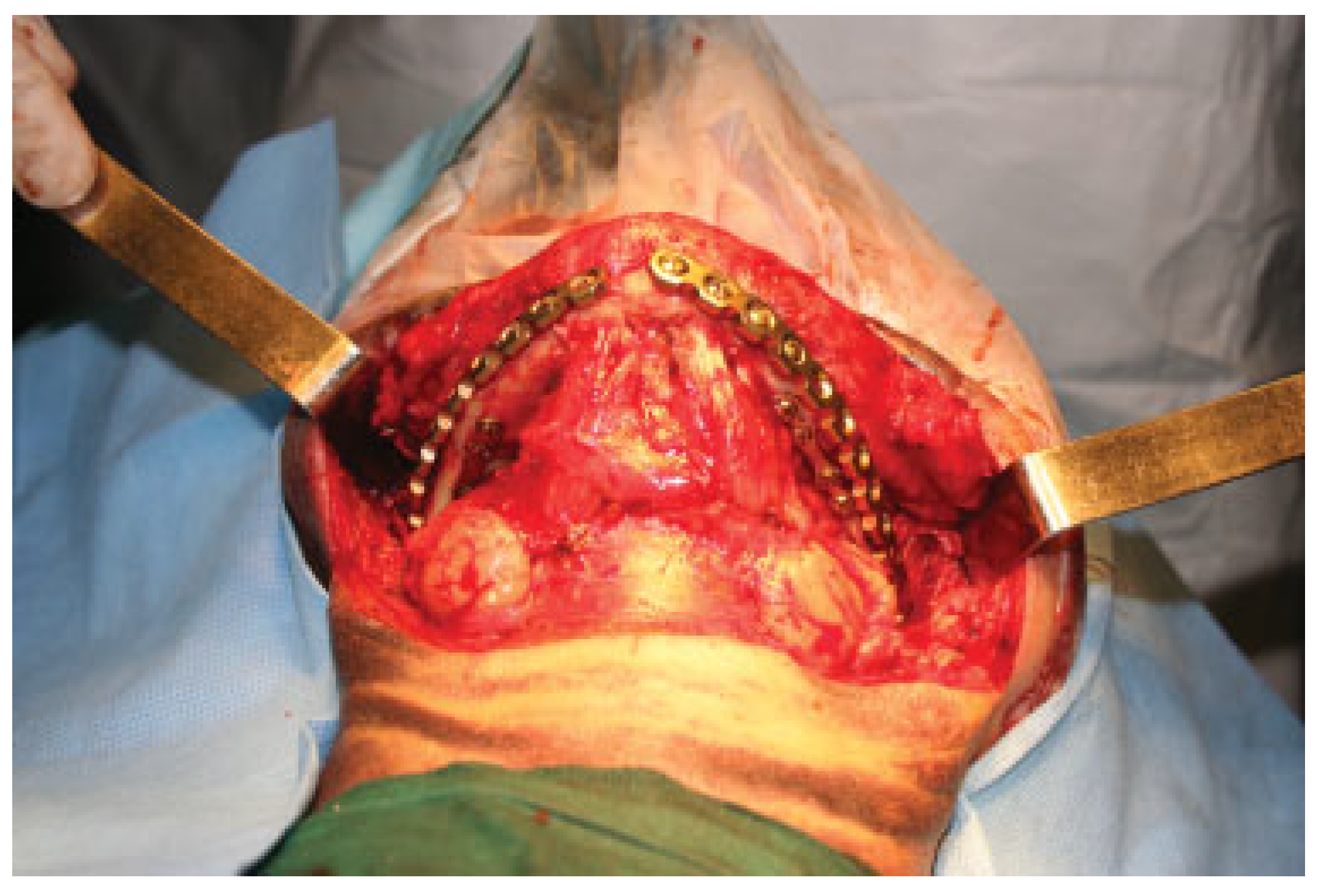

There are different types of techniques used to guide fragment’s reduction in edentulous mandibles. One of them, seldom used in our institution, is fixing the jaws in occlusion with the patient’s dentures held with screws to the bone (

Figure 3). It can also be very useful to temporarily maintain the mandibular alignment with miniplates fixated to the inferior border, before applying a larger plate to vestibular cortical bone. This technique was successfully employed in seven fractures of our series (

Figure 4). Furthermore, some authors use inferior border fixation with miniplates as the definitive treatment of the fracture [

7]. The latter technique presents the advantage that future denture adaptation is easier without the stronger osteosynthesis plate which is frequently larger than the mandible’s height. This author affirms that some of these patients are able to continue using the previous dentures [

7]. Madsen and Haug [

17] have studied reconstruction locking plate’s biomechanical behavior when fixated to mandibular replicas, divided into one group with osteosynthesis fixation to the buccal mandibular surface and a second group with fixation to the inferior border. This study could not demonstrate significant differences in mechanical behavior between the two specific experimental groups.

It has not been demonstrated that bicortical screws represent a higher risk for inferior alveolar nerve injury. Several times, the nerve is exposed due to mandibular atrophy and it can be separated from the mandible to prevent its laceration.

The relationship between the extent of mandibular atrophy and the incidence of fibrous unions or nonunions has been studied by many authors [

6,

18,

19].As we mentioned before, the greater the mandibular atrophy, the stronger the osteosynthesis plate recommended for fixation [

6,

18,

19]. The principle of load-bearing osteosynthesis provides an optimal stability.

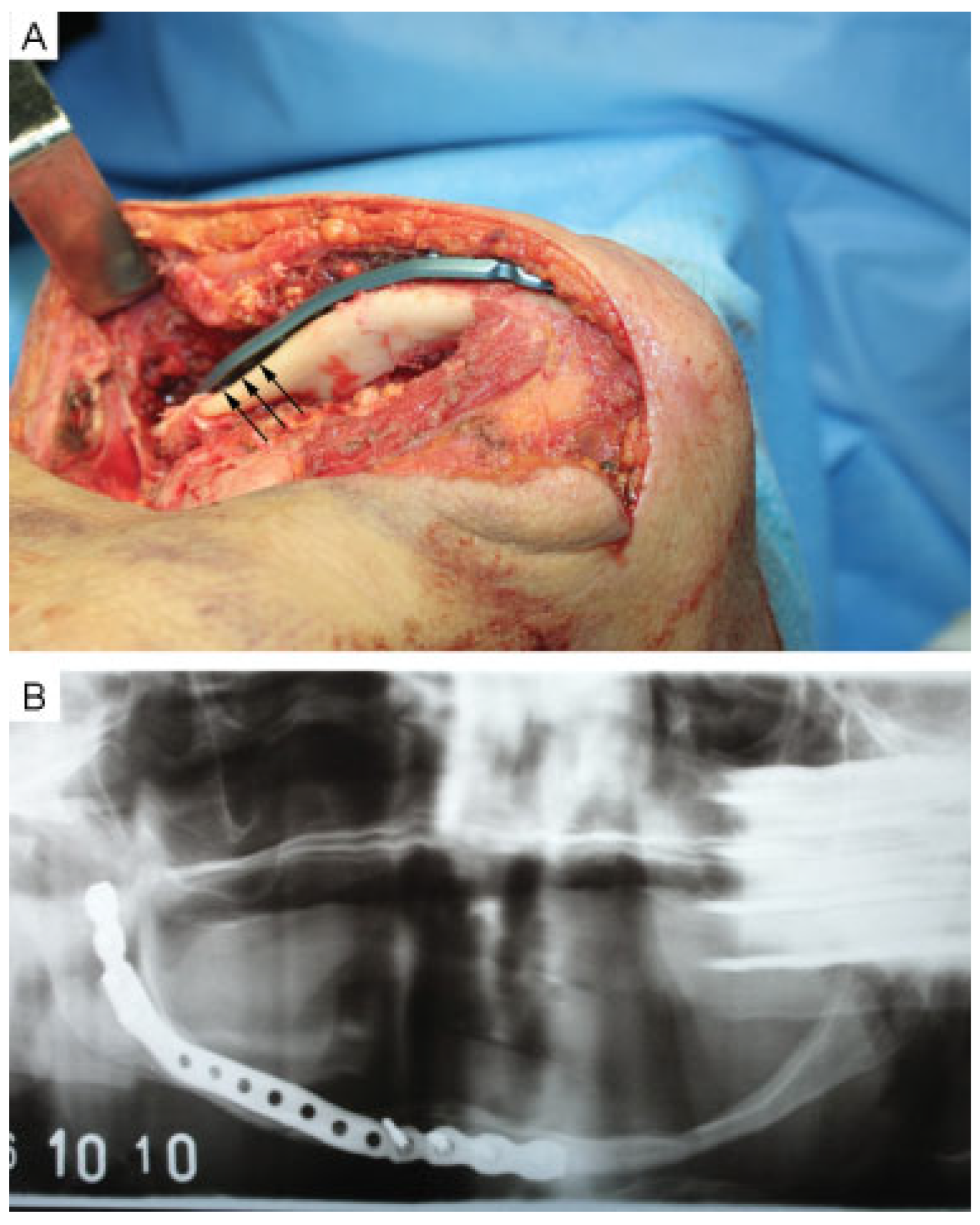

Atrophic bone cannot share loading forces of the mandible with the osteosynthesis material [

20]. Consequently, fixation with miniplates may derive in loose screws or plate breakage, leading to osteosynthesis failure [

21]. At present, locking systems are considered the gold standard of treatment [

22]; they present the advantage of admitting small bending defects (

Figure 5). In addition, if bone resorption occurs and a screw becomes loose, the latter will still be attached to the plate, and there is no need to remove the material. This system has also demonstrated the advantage of allowing a faster recovery of mastication [

14,

19]. Only one of our patients required bone grafting (

Figure 6). We agree with Melo et al. [

16] in recommending bone grafting in situations where there is great loss of bony tissue caused by comminution or debridement of infected tissue, or when treating nonconsolidated fractures [

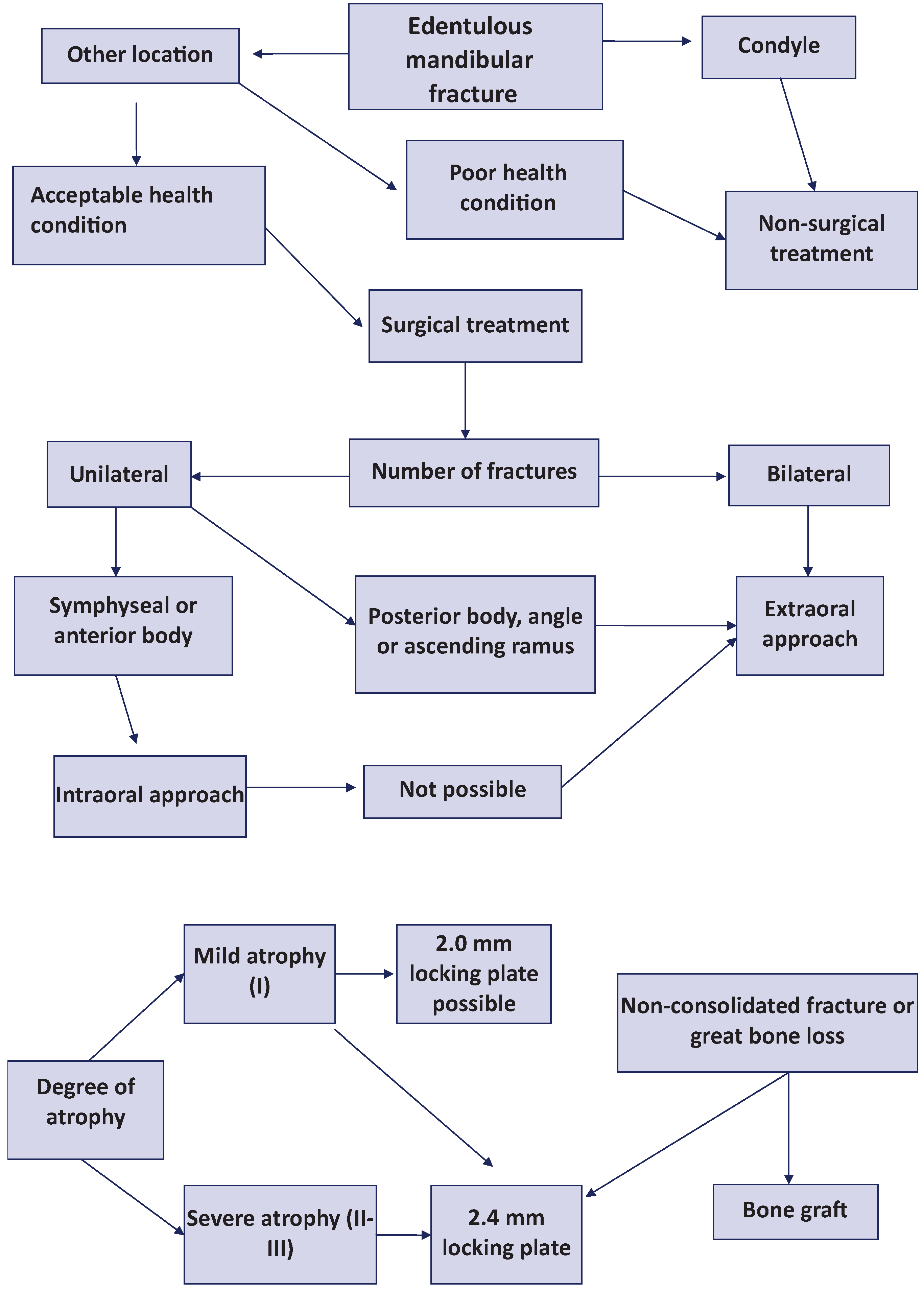

20]. On the basis of our review, we have developed an algorithm for treating edentulous mandibular fractures (

Figure 7).