Mandible and Zygomatic Fracture in a 2-Year-Old Patient Due to Dog Bite

Abstract

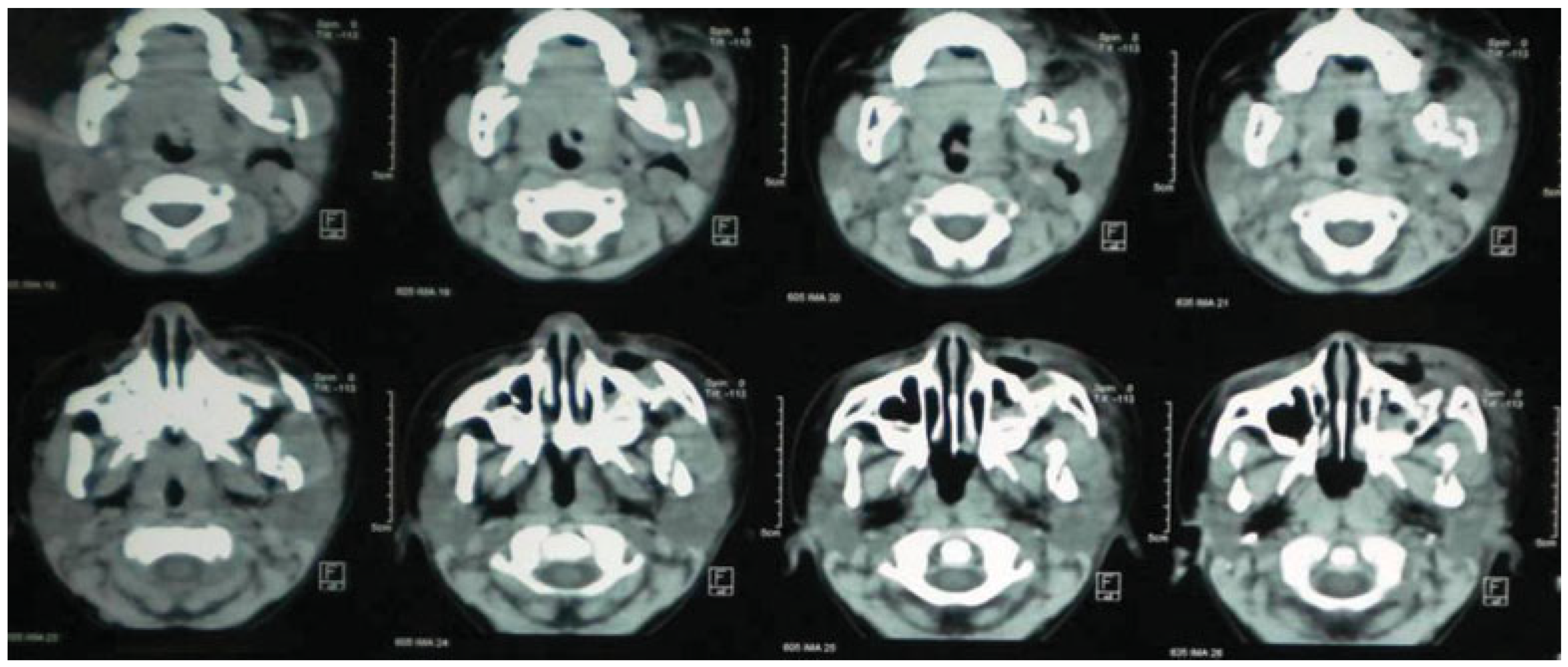

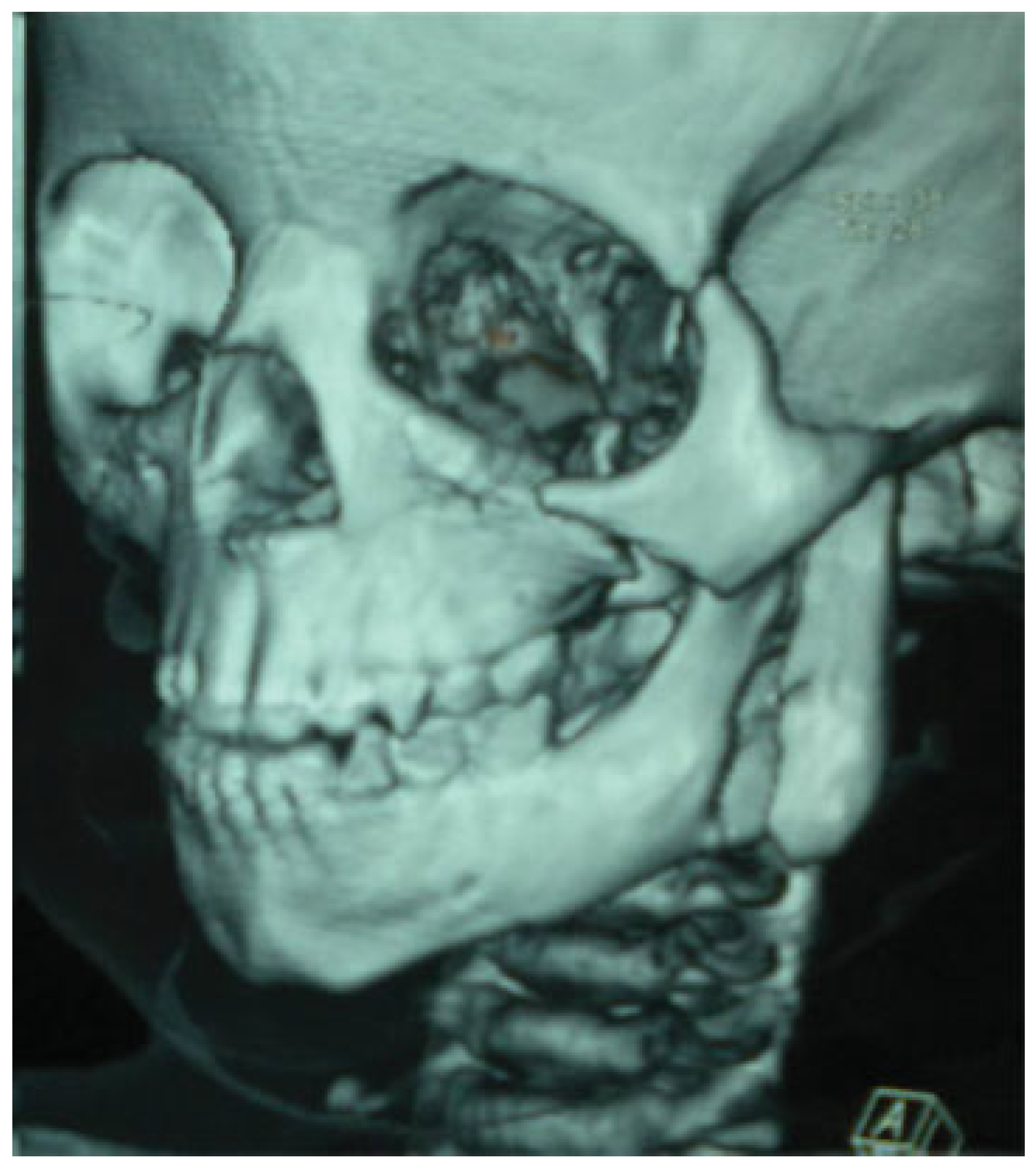

Case Report

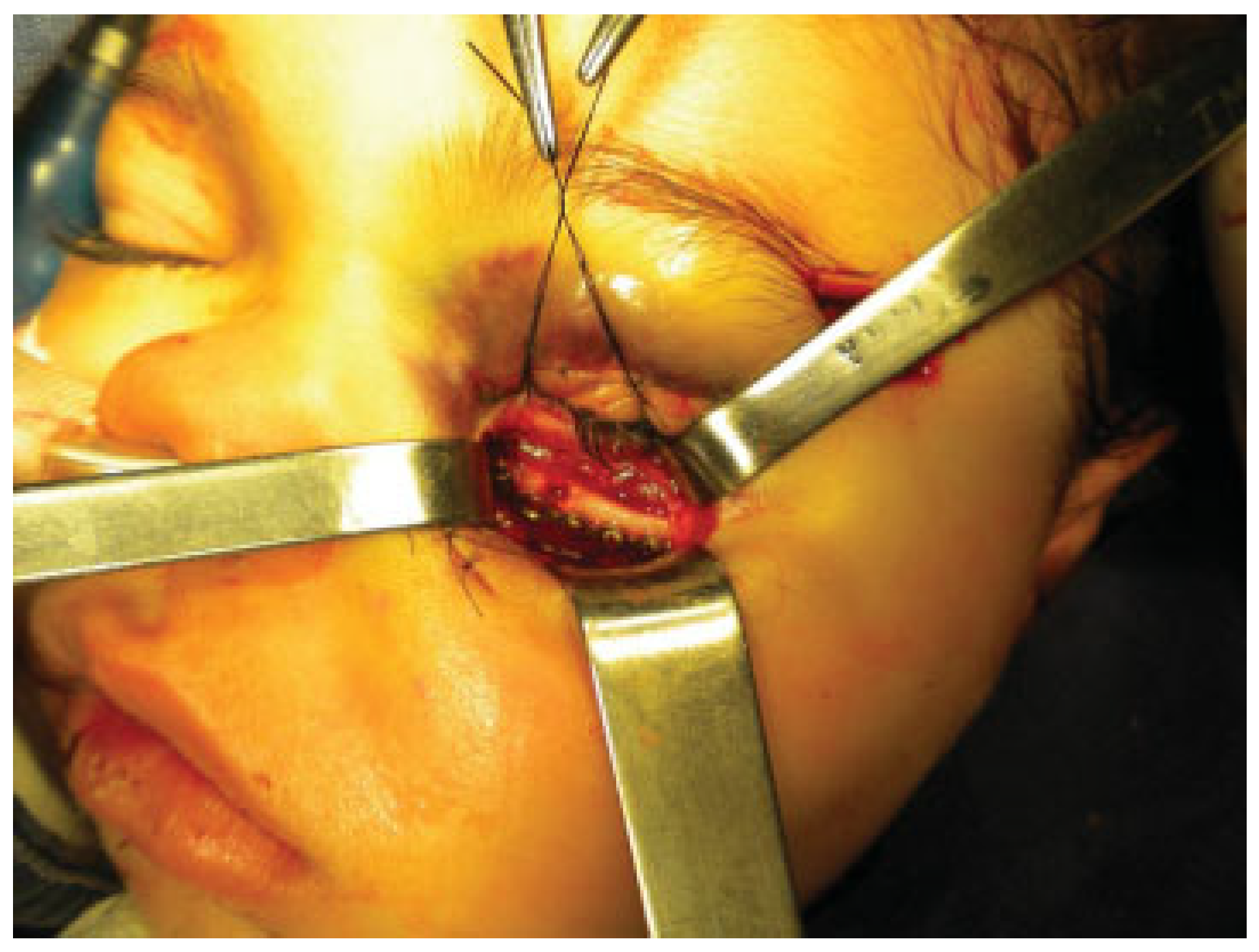

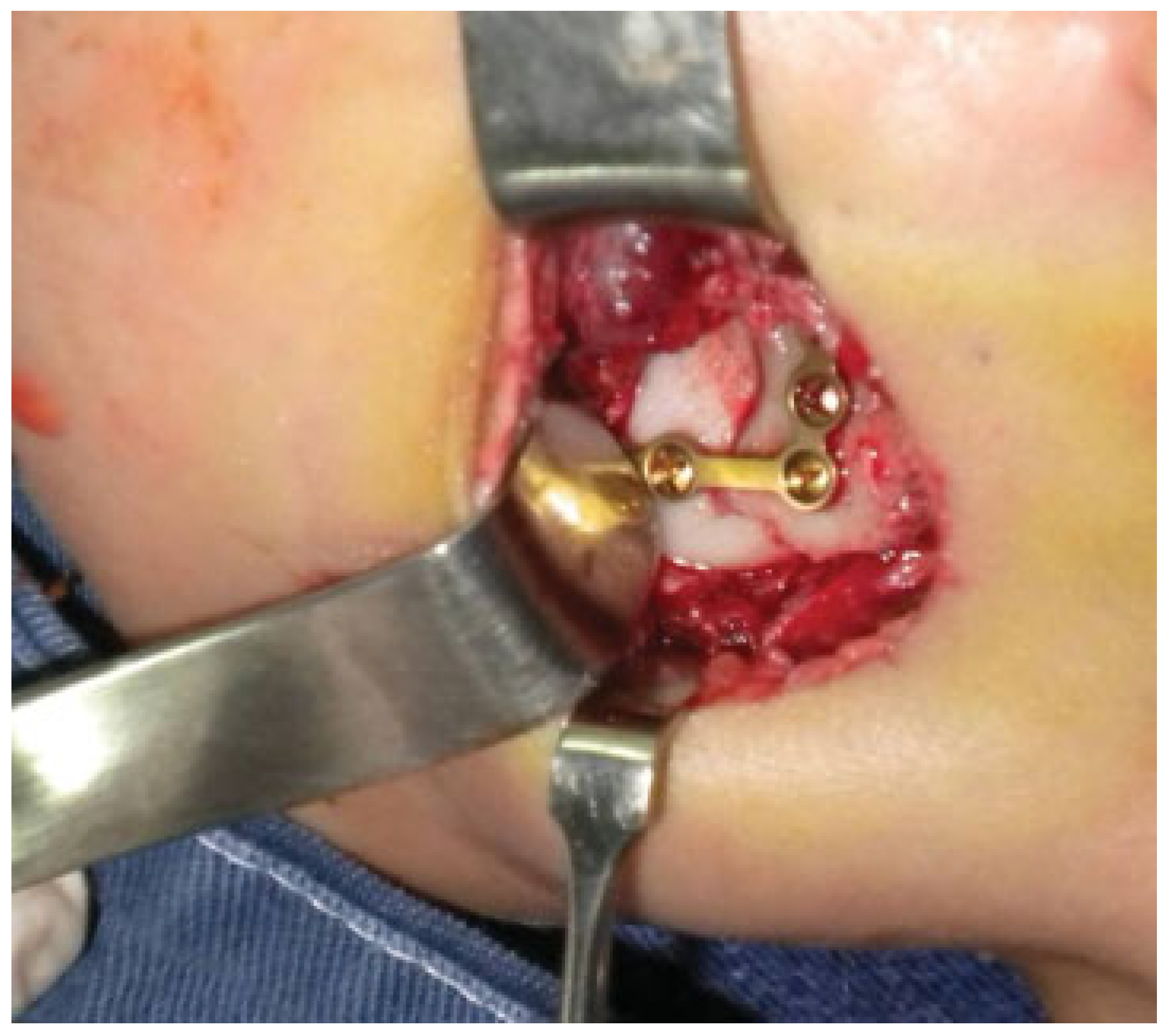

Procedure

Discussion

References

- Tu, A.H.; Girotto, J.A.; Singh, N.; et al. Facial fractures from dog bite injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002, 109, 1259–1265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hogg, N.J.; Stewart, T.C.; Armstrong, J.E.; Girotti, M.J. Epidemiology of maxillofacial injuries at trauma hospitals in Ontario, Canada, between 1992 and 1997. J Trauma 2000, 49, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, K.D. Management of animal bite injuries of the face: experience with 94 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998, 56, 838–843; discussion 843–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapuano, R.; Stratigos, G.T. Mandibular fracture resulting from dog bite: report of a case. J Oral Surg 1976, 34, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Case Report of Fractured Mandible in a Child Aged 1 Year. Available online: http://www.aofoundation.org/portal/wps/portal/!ut/p/_s.7_0_A/7_0_3K7?contentUrl=/aca/case_of_the/2006/08/ex_alumni_cases_0000024.jsp (accessed on 2 October 2012).

- Walker, T.; Modayil, P.; Cascarini, L.; Collyer, J. Dog bite-fracture of the mandible in a 9 month old infant: a case report. Cases Journal 2009, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottom, H.; Tuopar, D.; Ameerally, P. Mandibular fracture in a child resulting from a dog attack: a case report. Case Reports in Dentistry 2011, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Palmer, J.; Rees, M. Dog bites of the face: a 15 year review. Br J Plast Surg 1983, 36, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schalamon, J.; Ainoedhofer, H.; Singer, G.; et al. Analysis of dog bites in children who are younger than 17 years. Pediatrics 2006, 117, e374–e379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlson, T.A. The incidence of facial injuries from dog bites. JAMA 1984, 251, 3265–3267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lidner, D.; Marretta, H.; Pijanowski, G.; Johnson, A.; Smith, C. Measurament of bit force in dogs to pilot study. Veterinary Dentistry 1995, 12, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaremchuk, M.J. Revisional surgery of nasoethmoidal orbital fractures. In Operative Techniques in Plastic Surgery; Manson, P.N., Ed.; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Merville, L.; Vincent, J. Traumatismes de la face. Fractures du malaire. Fractures de la corniche zygomatique. Encycl Méd Chir 1992, 3, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Merville, L.; Vincent, J. Traumatismes de la face. Fractures mandibulaires. Encycl Méd Chir 1992, 3, 23–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dufresnese, C.; Manson, P. Cirugía Plástica McCarthy. Traumatismos faciales en niños. Ed. Med Panam 1991, 269–313. [Google Scholar]

- Maimaris, C.; Quinton, D.N. Dog-bite lacerations: a controlled trial of primary wound closure. Arch Emerg Med 1988, 5, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, L.K.; Chow, L.K.; Chiu, W.K. A randomized controlled trial of resorbable versus titanium fixation for orthognathic surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2004, 98, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Costa, F.; Robiony, M.; Zerman, N.; Zorzan, E.; Politi, M. Bone biological plate for stabilization of maxillary inferior repositioning. Minerva Stomatol 2005, 54, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fedorowicz, Z.; Nasser, M.; Newton, J.T.; Oliver, R.J. Resorbable versus titanium plates for orthognathic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007, 2, CD006204. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, J.A.; Ricci, J.L.; Di Cesare, P.E. Bioresorbable fracture fixation in orthopedics: a comprehensive review. Part I. Basic science and preclinical studies. Am J Orthop 1997, 26, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2013 by the author. The Author(s) 2013.

Share and Cite

Baldi, J.R.M.; Wolff de Freitas, D.A. Mandible and Zygomatic Fracture in a 2-Year-Old Patient Due to Dog Bite. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2013, 6, 137-141. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1333879

Baldi JRM, Wolff de Freitas DA. Mandible and Zygomatic Fracture in a 2-Year-Old Patient Due to Dog Bite. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2013; 6(2):137-141. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1333879

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaldi, Jesús R. Manzani, and Daniel A. Wolff de Freitas. 2013. "Mandible and Zygomatic Fracture in a 2-Year-Old Patient Due to Dog Bite" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 6, no. 2: 137-141. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1333879

APA StyleBaldi, J. R. M., & Wolff de Freitas, D. A. (2013). Mandible and Zygomatic Fracture in a 2-Year-Old Patient Due to Dog Bite. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 6(2), 137-141. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1333879