Transfusion Requirements in Microsurgical Reconstruction in Maxillofacial Surgery: Ethical and Legal Problems of Patients Who Are Jehovah's Witnesses

Abstract

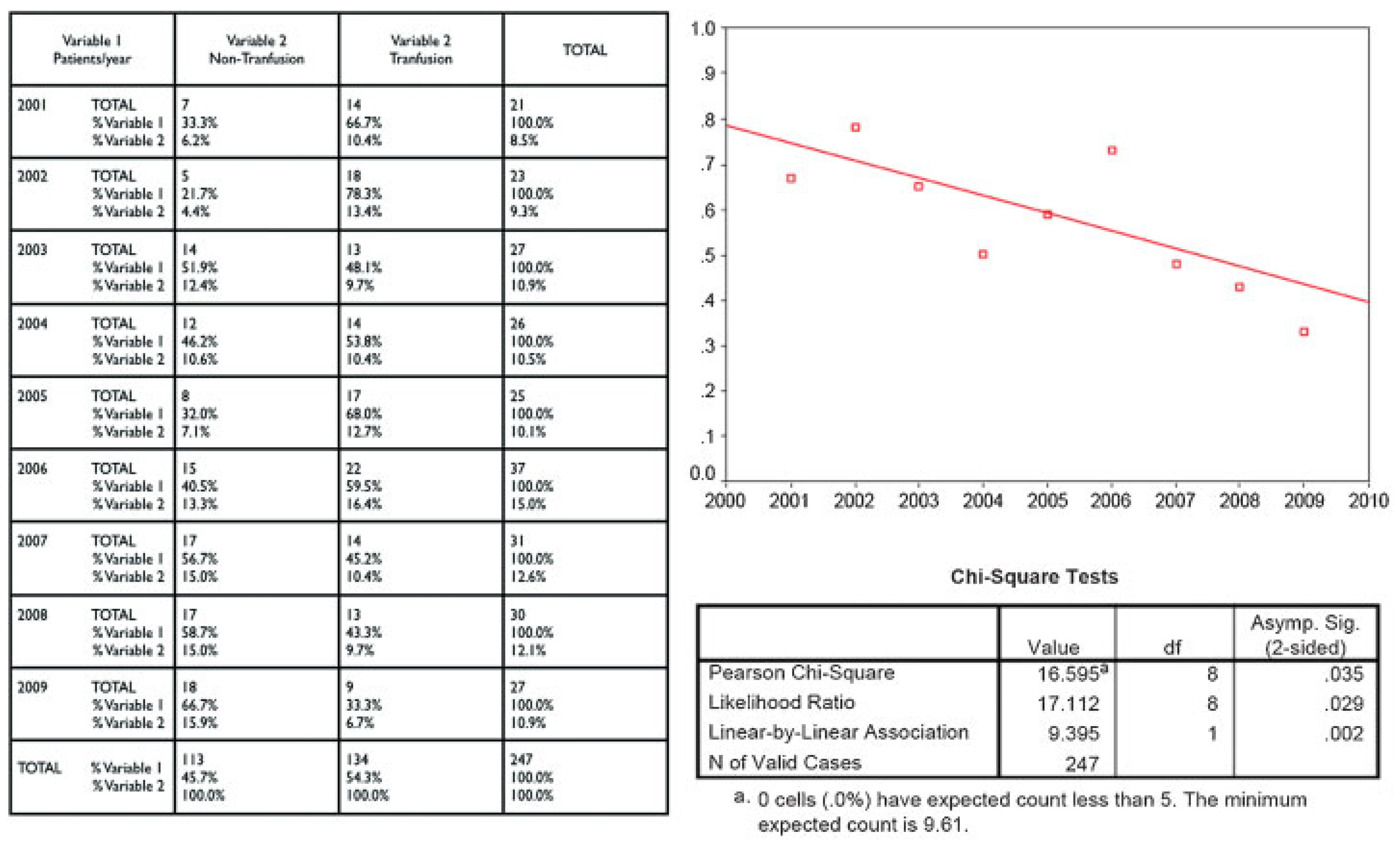

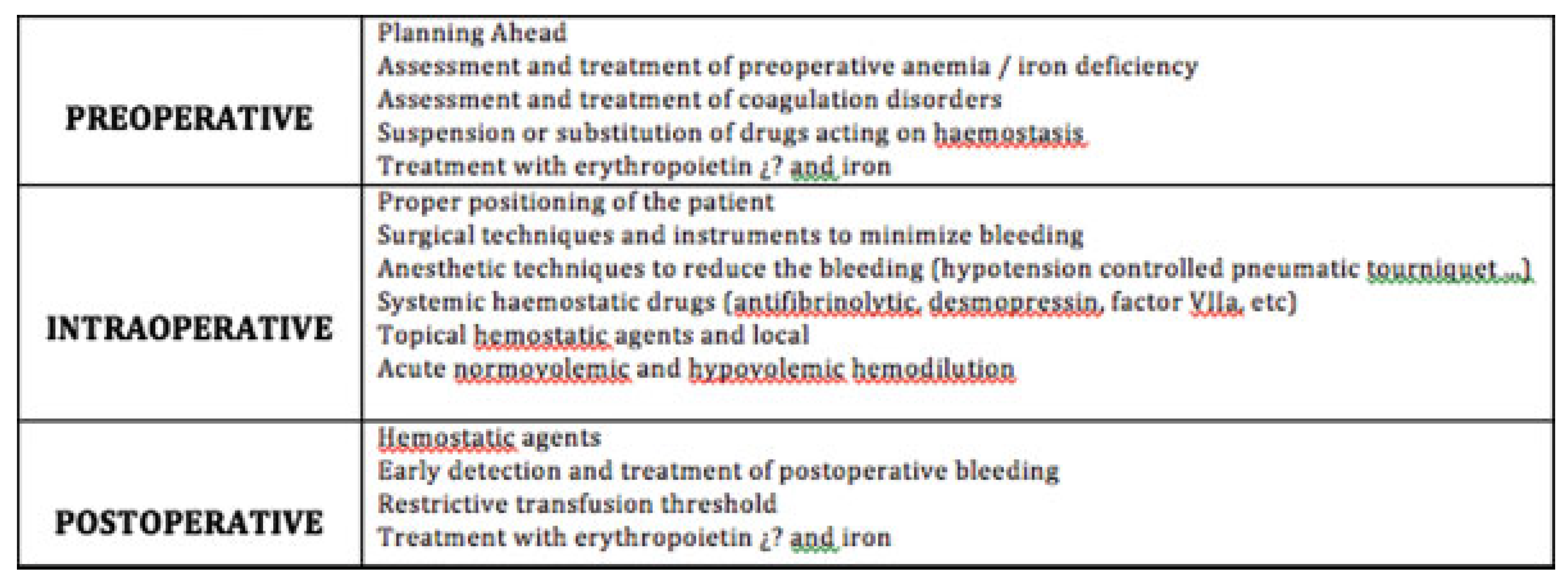

:Materials and Methods

Results

Discussion

Surgeon’s Performance Key to a Jehovah’s Witness Patient

- Interview the patient to ensure that his or her decision to reject blood is firm, without being influenced by family or friends. The surgeon should inform the patient of the available alternatives and the risks of not being transfused if a serious situation is presented, as well as the risks of alternative treatments such as tumor progression after the administration of rHuEPO.

- It can be helpful, patient permitting, to contact the Liaison Committee of the Hospitals of the Jehovah’s Witnesses (LCH). The LCH is composed of volunteer members of this doctrine whose mission is to promote physician–patient cooperation and serve as intermediaries providing support to these patients on ethical issues relating to health care. The LCH can provide medical documentation of blood-saving methods and alternatives to blood transfusion. Currently there are 40 LCH in Spain coordinated by the Hospital Information Service of the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

- The surgeon can make use of the right to conscientious objection, but his or her duty is to delegate and refer the case to be appropriately treated by another specialist.

- It is very important that anesthesia service and intensive postoperative care maximize savings measures.

Conclusion

References

- Harrison, B.G. Visions of Glory: A History and Memory of Jehovah’s Witnesses; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley, S.L.; Smith, D.R.K. ENT surgery, blood and Jehovah’s Witnesses. J Laryngol Otol 2007, 121, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pérez Ferrer, A.; Gredilla, E.; de Vicente, J.; García Fernández, J.; Reinoso Barbero, F. Is Jehovah’s Witnesses refusal of blood: Religious, legal and ethical aspects and considerations for anesthic management. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2006, 53, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bodnaruk, Z.M.; Wong, C.J.; Thomas, M.J. Meeting the clinical challenge of care for Jehovah’s Witnesses. Transfus Med Rev 2004, 18, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New Light on Blood. Bible and Tract Society of New York; 2010. Available at: www.ajwrb.org (accessed on 13 September 2006).

- Dulguerov, P.; Quinodoz, D.; Allal, A.S.; Tassonyi, E.; Beris, P. Blood transfusion requirements in otolaryngology—Head and neck surgery. Acta Otolaryngol 1998, 118, 744–747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Opelz, G.; Sengar, D.P.; Mickey, M.R.; Terasaki, P.I. Effect of blood transfusions on subsequent kidney transplants. Transplant Proc 1973, 5, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Woolley, A.L.; Hogikyan, N.D.; Gates, G.A.; Haughey, B.H.; Schechtman, K.B.; Goldenberg, J.L. Effect of blood transfusion on recurrence of head and neck carcinoma. Retrospective review and meta-analysis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1992, 101, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.T.; Taylor, F.H.; Thearle, P.B. Blood transfusion and outcome in stage III head and neck carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1987, 113, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jackson, R.M.; Rice, D.H. Blood transfusions and recurrence in head and neck cancer. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1989, 98, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Böck, M.; Grevers, G.; Koblitz, M.; Heim, M.U.; Mempel, W. Influence of blood transfusion on recurrence, survival and postoperative infections of laryngeal cancer. Acta Otolaryngol 1990, 110, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.R.; Weissler, M.C. Blood transfusion and other risk factors for recurrence of cancer of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1990, 116, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Doersten, P.; Cruz, R.M.; Selby, J.V.; Hilsinger, R.L., Jr. Transfusion, recurrence, and infection in head and neck cancer surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992, 106, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuller, D.E.; Scott, C.; Wilson, K.M.; et al. The effect of perioperative blood transfusion on survival in head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1994, 120, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gilcreast, D.M.; Avella, P.; Camarillo, E.; Mullane, G. Treating severe anemia in a trauma patient who is a Jehovah’s witness. Crit Care Nurse 2001, 21, 69–72, 75–78, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez Ferrer, A. Tratado de Medicina Transfusional; Editorial Panamericana: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rohling, R.G.; Zimmermann, A.P.; Breymann, C. Intravenous versus oral iron supplementation for preoperative stimulation of hemoglobin synthesis using recombinant human erythropoietin. J Hematother Stem Cell Res 2000, 9, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Constitución Española de 27 de diciembre de 1978 BOE 311/1978, de 29 diciembre 1978 ARTS. 11 y 149, 1 2°. Ref Boletín: 78/31229.

- Woolley, S. Jehovah’s Witnesses in the emergency department: What are their rights? Emerg Med J 2005, 22, 869–871. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2013 by the author. The Author(s) 2013.

Share and Cite

Martin, L.P.; Arias-Gallo, J.; Perez-Chrzanowska, H.; Seco, P.R.; Moro, J.G.M.; Burgueño-Garcia, M. Transfusion Requirements in Microsurgical Reconstruction in Maxillofacial Surgery: Ethical and Legal Problems of Patients Who Are Jehovah's Witnesses. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2013, 6, 31-36. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1333828

Martin LP, Arias-Gallo J, Perez-Chrzanowska H, Seco PR, Moro JGM, Burgueño-Garcia M. Transfusion Requirements in Microsurgical Reconstruction in Maxillofacial Surgery: Ethical and Legal Problems of Patients Who Are Jehovah's Witnesses. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2013; 6(1):31-36. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1333828

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartin, Lorena Pingarron, Javier Arias-Gallo, Hanna Perez-Chrzanowska, Pilar Ruiz Seco, Javier Gonzalez M. Moro, and Miguel Burgueño-Garcia. 2013. "Transfusion Requirements in Microsurgical Reconstruction in Maxillofacial Surgery: Ethical and Legal Problems of Patients Who Are Jehovah's Witnesses" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 6, no. 1: 31-36. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1333828

APA StyleMartin, L. P., Arias-Gallo, J., Perez-Chrzanowska, H., Seco, P. R., Moro, J. G. M., & Burgueño-Garcia, M. (2013). Transfusion Requirements in Microsurgical Reconstruction in Maxillofacial Surgery: Ethical and Legal Problems of Patients Who Are Jehovah's Witnesses. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 6(1), 31-36. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1333828