The integrity of the zygoma is critical in maintaining normal facial width and prominence of the cheek. Sicher and DeBrul were the first to depict facial anatomy and recognize the structural pillars or buttresses of the facial skeleton [

1]. Several buttresses abut the zygoma to three major bone units in the face—the temporal bone, the frontal skull, and the maxilla—giving the best architectural and stress-bearing functional struts, which can transmit force in different directions, protecting the eye and the brain. These buttresses also give the zygoma an intrinsic strength such that blows to the cheek usually result in fractures of the zygomatic complex at the suture lines and, less commonly, the body of the zygomatic bone. Studies on the incidence of zygoma fractures have shown that road traffic accidents (RTAs; 31%) and assaults are the commonest causes of zygomatic complex fractures. Tetrapod fractures (43.7%) were the more frequently reported compared with isolated zygomatic arch fractures (34.53%) [

2]. (

Tetrapod is term used to describe zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture.

Tetrapod means ‘‘four processes.’’) Fractures of the zygomatic complex either occur unilaterally in isolation or may be associated with other facial skeletal components, such as Lefort fractures, where zygoma fractures may be bilateral. Isolated bilateral zygomatic complex and arch fracture are extremely rare, and in the literature no such report of a case exists. We present one such rare case without any other associated facial bone fractures.

Case Report

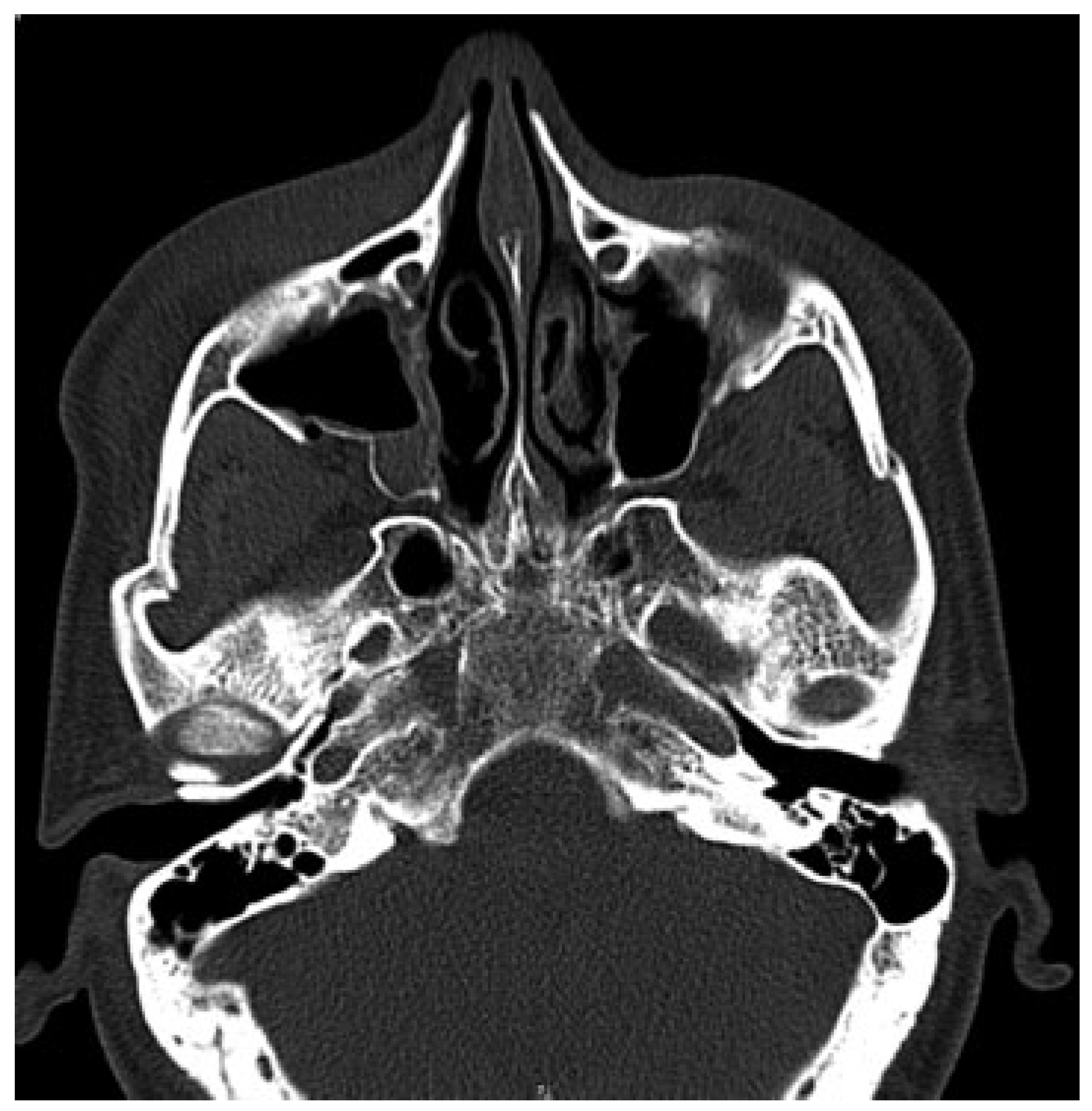

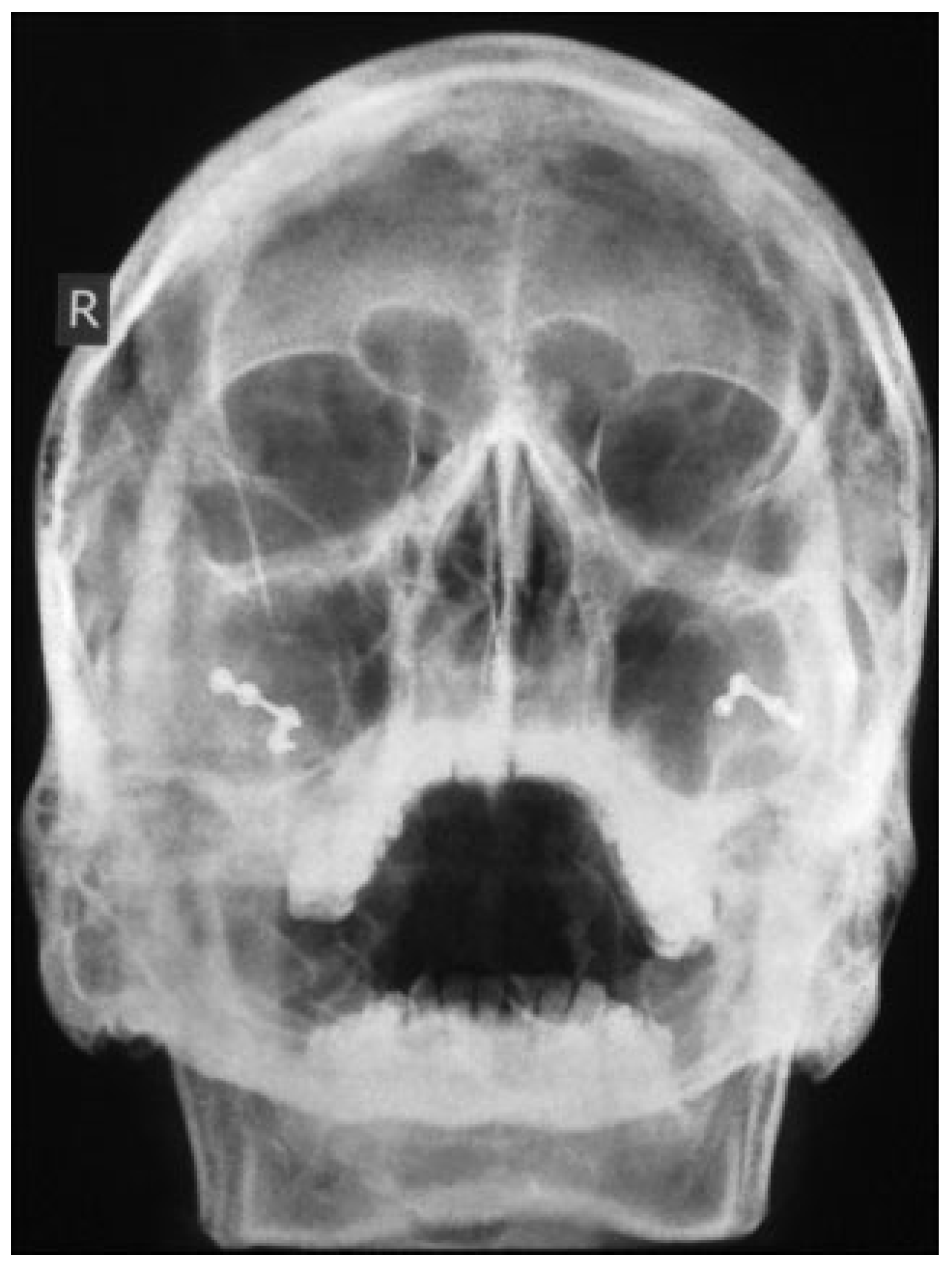

A 35-year-old male patient presented to Accident and Emergency Department with facial injuries associated with RTA. As per the patient, he collided with another motorbike and was not wearing a helmet at the time of accident. On examination, he had bruises on bilateral zygomatic areas and a 2-cm laceration on the right supratarsal fold close to zygomaticofrontal suture. The right and left zygoma were tender on palpation and associated with depression of zygomatic arch areas. Infraorbital paresthesia was present on the right side. Trismus was moderate, and a detailed clinical and computed tomography examination showed displaced bilateral isolated zygomatic complex (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) and arch fractures (

Figure 3) without any other associated facial bone fractures. He underwent open reduction and internal fixation of both zygomatic complexes including the closed reduction of the arch by Gillies approaches and fixation via an intraoral approach at the Lefort level I (

Figure 4). The postoperative recovery was uneventful with good mouth opening and with no cosmetic deficit.

Discussion

The zygoma is the second most common site of facial bone fracture. The vast majority of zygomatic fractures occur in men in their third decade of life. The incidence of isolated bilateral zygomatic fractures has not been reported secondary to RTA apart from one such report of a bilateral zygomatic arch fracture [

3]. In 1994, Covington et al. reviewed 259 patients with zygomatic fractures and found that zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures occurred in 78.8% of patients, isolated orbital rim fractures occurred in 10.8% of patients, and isolated arch fractures occurred in 10.4% of patients. Of the isolated arch fractures, 59.3% were displaced or comminuted [

4].

The exact mechanism of how bilateral zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures alone occur after RTA is difficult to explain but can be attributed to two separate impacts with two trajectories of forces occurring as the patient was thrown out of the vehicle. In our case, the right side was more displaced than the left, probably due to the fact that the first impact on the right was more forceful than the impact on the left. When bilateral fractures occur, it is more difficult to assess the symmetry of reduction, in contrast to unilateral fractures where an unaffected side may be used as a clinical guide for symmetry. It is always better, in our opinion, to reduce and fix the side that is less displaced and then fix the more displaced fragment for better orientation and symmetry. In this case, the occlusion was not disturbed, and there was no maxillary mobility of a Lefort maxillary fracture where of course bilateral zygoma fractures are seen. The factors to consider in reduction were to anatomically reduce the malar prominence and the zygomatic arch for symmetry, function, and the restoration of orbital volume.

This case report of a bilateral zygoma fracture is rare. The sites of impact force in the facial bones and the management pertaining to this fracture (complex bilateral zygomatic fractures not involving the occlusion) are illustrated.