Introduction

Facial fracture is a traumatizing event for patients, the effects of which may be exacerbated by complications of operative repair. The mandible is among the most frequently fractured bones in patients with craniomaxillofacial trauma; some series have identified mandible fractures occurring in more than 60% of cases [

1]. Surgical treatment is often essential to improve these patients’ functional and aesthetic outcomes. However, operative repair is frequently marked by complication, with rates reported in the literature ranging from 7.8% to 27% or higher [

1,

2,

3]. These complications have significant consequences, and a multifactorial understanding of complication risk would serve patients, providers, and hospital systems.

It is important to recognize the human suffering that results from mandible fracture, operative repair, and any subsequent complications. Following the inciting trauma and initial injury, patients must endure surgery and often a subsequent period of maxillomandibular fixation. Complications following operative repair can lead to pain, disruption of work and daily activities, and possible long-term disfigurement [

4]. For providers and hospital systems, the ramifications of surgical complications are less direct but consequential nonetheless. In general, surgical management of craniomaxillofacial trauma is associated with increased opportunity costs for surgeons and lower hospital reimbursement rates [

5]. This economic burden threatens the sustainability and accessibility of this care, particularly when associated with poor outcomes [

6]. Previous literature has investigated the clinical factors that may contribute to surgical complications following operative mandible repair. However, given the continued high complication rate observed after these surgeries, a more granular characterization of both clinical and social risk factors is warranted.

To this end, we examined all mandible fractures treated between 2015 and 2020 at our Level I Trauma Center, situated in a federally designated

Medically Underserved Area [

6]. The objectives of this study were twofold. First, we sought to identify those factors that put patients at greatest risk for postoperative complications, with a particular focus on social determinants of health. Based on previous literature characterizing risk factors in similarly vulnerable populations, specific attention was paid to patient substance and tobacco use history, duration between injury and operative intervention, and antibiotic duration [

1,

7,

8]. Furthermore, the Area Deprivation Index (ADI) was used to capture neighborhood-level differences in social determinants of health. The ADI is a well-validated metric incorporating 17 variables extrapolated from US Census and American Community Survey data that approximates an individual’s socioeconomic surroundings. Higher ADI values reflect the increased burden of social determinants of health [

9]. The secondary purpose, and much of the motivation behind this work, was to suggest risk mitigation strategies that may improve future outcomes for the most vulnerable patients.

Methods

Study Design and Patient Cohort

Prior to data collection, approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board, IRB number 26604. A retrospective chart review was conducted to identify all patients treated for mandible fractures between January 2015 and December 2020. Patients were identified based on ICD-9/ICD-10 codes for mandible fractures and CPT codes for mandible fracture repair. Among the identified cases, operations were performed by surgeons from the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, the Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, and the Department of Otolaryngology. The study inclusion criteria selected for all adult patients over the age of 18 who were treated surgically for mandible fracture within the investigation time period. Pregnant patients and incarcerated patients were excluded. A total of 272 patients were included in the analysis.

The electronic medical record was reviewed for each subject, and data were collected regarding patients’ clinical courses. Data points included demographic information, medical comorbidities (history of coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, HIV infection, Hepatitis C infection, Hepatitis B infection), behavioral health disease diagnoses (anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia), substance use history, admission urine drug screen, mechanism of injury, characteristics of mandible fracture(s), additional injuries sustained, the interval from injury to presentation, the interval from injury to surgery, the interval from admission to surgery, duration and choice of preoperative antibiotics, and operative conduct. Data were also collected from chart review of follow-up visits. Variables of interest included the number of completed follow-up visits and total follow-up duration, description of oral hygiene, documented adherence to oral hygiene instructions, and adherence to dietary restrictions. Data reflecting social determinants of health were collected from social work documentation and included housing instability, history of domestic violence, and postoperative discharge destination. An Area Deprivation Index was determined for each patient using their home address as listed in the electronic medical record.

Postoperative Complications

Details regarding postoperative complications were extracted from the index hospitalization or descriptions of postoperative outpatient visits and subsequent hospitalizations. Complications included wound dehiscence, infection, malocclusion, nonunion, and hardware failure, and were documented with any respective management (e.g., bedside procedure, medical management, unplanned return to the operating room). Notably, hardware failure was defined as situations involving inadvertent screw loosening, plate fracture, hardware erosion and exposure, and bone resorption. Complications were stratified into major and minor complications in the manner described by Chen et al. [

1] Major complications were defined as those requiring a return to the operating room: wound dehiscence, abscess formation requiring operative debridement, hardware failure, and subsequent nonunion. Minor complications included any that were addressed without the need for further surgery, including wound dehiscence managed non-operatively, infection treated with antibiotics alone, abscess formation managed at the bedside, and malocclusion. Additionally, major and minor complications were assessed in binary fashion, in that patients either did or did not experience said complication.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized with mean, frequency, median, and interquartile range. All continuous variables were tested for normality with the Kolmogorov– Smirnov test. Continuous, normally distributed variables were compared with the Independent Student’s T-test. Continuous, non-normally distributed variables were assessed with the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared with Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Variables that contained incomplete datasets were treated as missing completely at random and were addressed with the missing indicator method [

10]. Variables significant on univariable analysis (

P-value < .05) were included in multivariable logistic regression. Multivariable logistic regression models were generated through best subset selection. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

Results

Demographics

From January 2015 to December 2020, 272 patients were identified, representing 576 distinct mandible fractures. Most patients were male (83%), and 55% were African American. The median age was 33 years (IQR 26–42). The overwhelming majority of mandibular trauma in our sample was secondary to interpersonal violence, primarily assault (69% of patients), with an additional six percent of patients sustaining mandible fractures from gunshot wounds. Additional mechanisms of injury included motor vehicle and motorcycle accidents, falls, pedestrians struck by motor vehicles, and bicycle accidents.

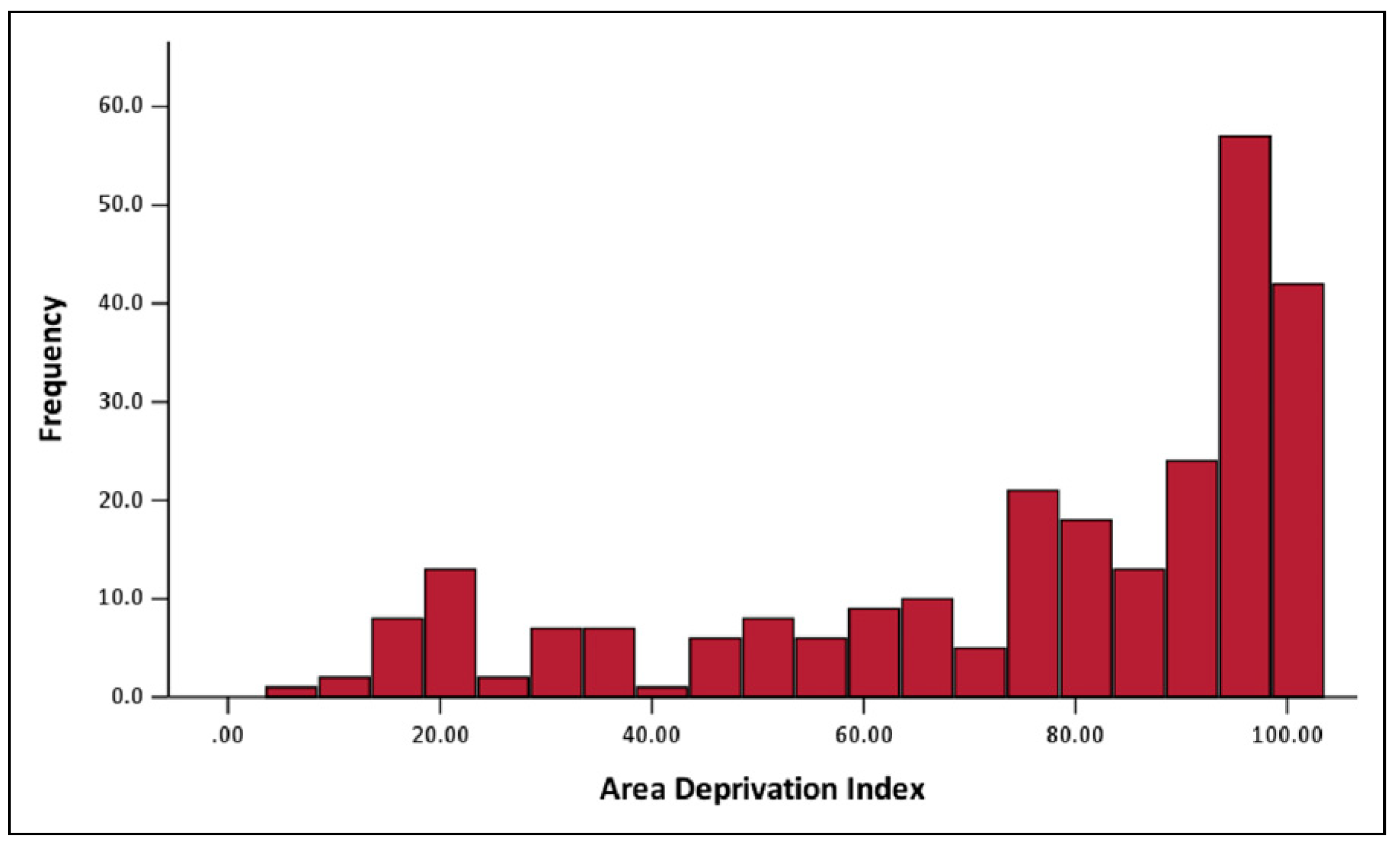

Based on ZIP Code, patients most commonly presented from the Kingessing and Hunting Park neighborhoods (13.2% and 12.5%, respectively) in Philadelphia, PA. Based on residential address, the median Area Deprivation Index for the cohort was 86 (IQR 59.25–96),

Figure 1.

Comorbidities, Substance Use, and Social History

Sixty-five patients (24%) presented with at least one medical comorbidity; diabetes was the most common condition, present in 21 patients (8%). Sixty patients (22%) carried a behavioral health disease diagnosis. Depression was the most common behavioral health disorder, present in 34 patients (13%).

Substance use was prevalent in this cohort; 156 patients (57%) had a history of substance use disorder based on chart review, and 81 patients (30%) had a positive urine drug screen on admission. The most commonly used substance was marijuana; 110 patients (40%) currently or formerly used marijuana. Likewise, tobacco use was common; 168 patients (62%) were either present or former tobacco users (including cigarette, e-cigarette, and dip/chew modalities). Other substances used included opioids (16%), cocaine (10%), benzodiazepines (8%), phencyclidine (7%), and amphetamines (4%).

Twenty-three patients (8.4%) were experiencing housing instability or homelessness at the time of presentation, and domestic violence was reported by 21 patients (7.7%).

Injury Type, Operative Repair, and Hospitalization

The mandibular angle was the most common fracture location (24%), followed by the parasymphysis (21%), body (20%), ramus (13%), subcondyle (7%), coronoid process (7%), condyle (4%), symphysis (4%), and alveolar ridge (1%),

Figure 2A. The median interval from admission to surgery was two days (IQR 1–3 days and the median interval from injury to surgery was three days (IQR 2–5 days). Operative technique was employed at the discretion of the attending surgeon; in 73% of cases, the fracture was repaired with open reduction and internal fixation with concomitant maxillomandibular fixation (MMF),

Figure 2B. Two hundred forty-seven patients (94%) underwent MMF; the most commonly chosen method for fixation was intermaxillary screws with stainless steel wire (48% of patients). Ninety-seven percent of patients received antibiotics preoperatively with a median duration of three days (IQR: 2–5 days).

The median overall length of stay was three days (IQR: 2–5 days), with a median postoperative length of stay of one day (IQR: 1–2 days). In terms of discharge disposition, 215 patients (79%) were discharged to home, while 10 (3.6%) were discharged to a skilled nursing facility or acute rehabilitation, and 10 (3.6%) were discharged to a shelter or the street.

Follow-Up Characteristics

Patients in this cohort had a median follow-up duration of 50 days (IQR 31–111 days2). Postoperative follow-up was arranged for all patients, and 48% attended at least one postoperative clinic appointment. Approximately 34% of patients attended four or more postoperative clinic visits. Of patients who presented for follow-up, documentation indicated that 39% adhered to the recommended dental soft diet prescribed postoperatively, and 29% used tobacco products postoperatively.

Major and Minor Complications

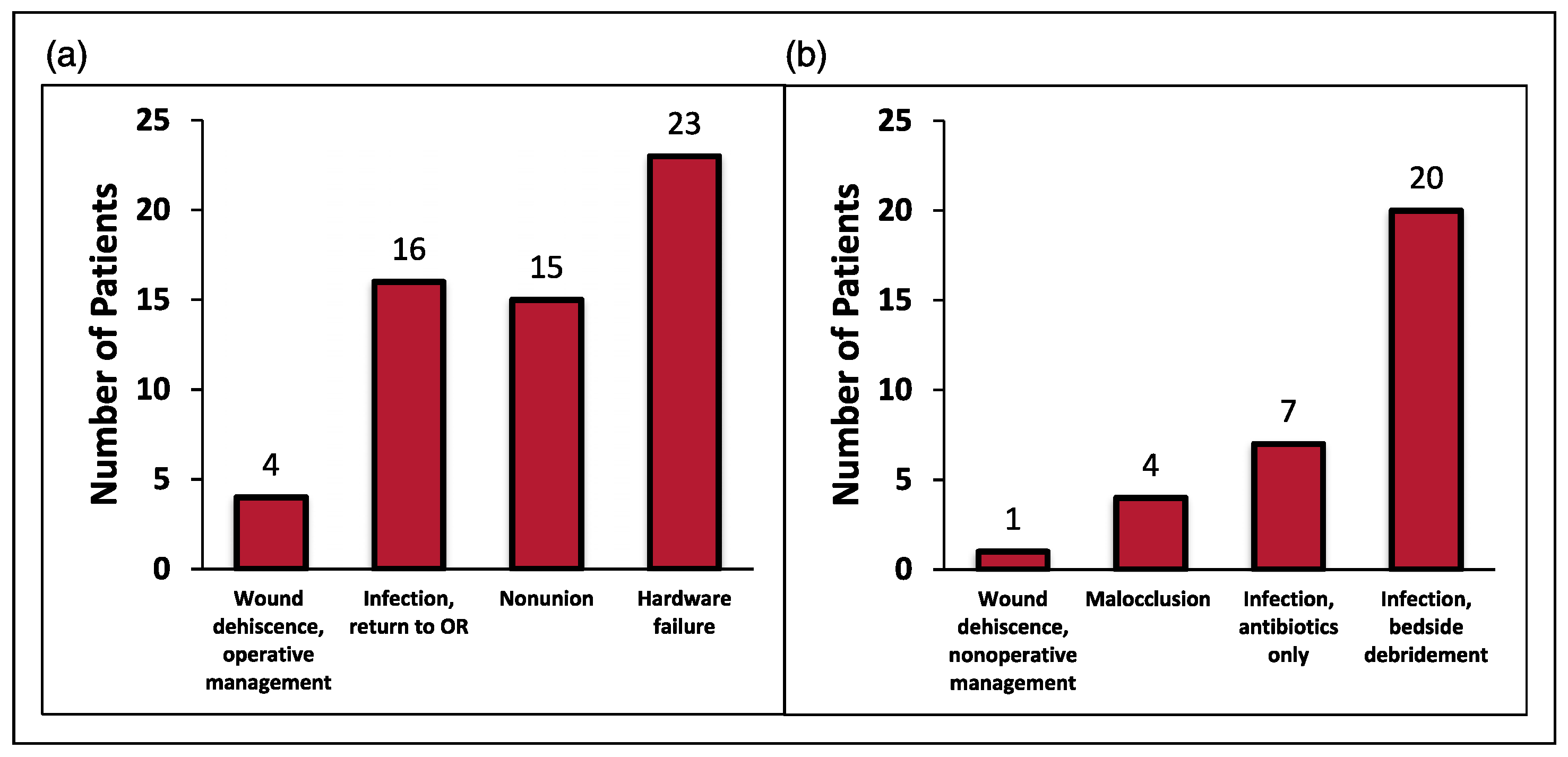

On follow-up, 58 patients experienced a postoperative complication after their index operation, a complication rate of 21.3%. These complications were stratified into major and minor complications. There were 58 instances of major complications and 39 instances of minor complications. Twelve patients experienced two or more complications, and three patients experienced three or more complications. The most common major complication was hardware failure (23 cases, 8.5%), while infection was the most common minor complication (27 cases, 9.9%). Major and minor complications are represented in

Figure 3a and

Figure 3b, respectively.

Missing Data

The following variables were noted to contain missing data: dietary nonadherence (107 patients missing data) and attendance of routine follow-up visits (141 patients missing data). Data missing from these categorical variables were coded as indicator variables.

Major Complications, Univariable Analysis

Preoperative Factors. On univariable analysis, the following factors were found to be significantly correlated with major complications: history of Hepatitis C (OR 6.88, 95% CI 2.10–22.60), history of behavioral health disease diagnosis (OR 2.99, 95% CI 1.46–6.12), history of cocaine use disorder (OR 3.54, 95% CI 1.69–7.40), history of opioid use disorder (OR 3.80, 95% CI 1.78–8.10), mandible body fracture location (OR 2.76, 95% CI 1.36–5.58), Area Deprivation Index (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.002–1.04), and tobacco use (OR 3.77, 95% CI 1.52–9.36).

Furthermore, several preoperative risk factors were not significantly correlated with major complications, including a history of diabetes mellitus, HIV infection, positive results on admission urine drug screen, housing instability, mechanism of injury, or history of recent domestic violence. Similarly, concomitant facial fractures (Le Fort I/II/III injuries), cervical spine fractures, and associated skull fractures were not significantly correlated with major complications.

Notably, the median duration of antibiotic therapy prior to operation did not differ significantly between those patients that experienced a major complication and those that did not (P = .45). Likewise, the median duration from injury to operative repair did not differ significantly between these two patient groups (P = .133).

Operative Factors. Specific operative techniques were not statistically correlated with major complications.

Postoperative Factors. The following postoperative factors were correlated with an increased risk of major complications: discharge to a drug or alcohol rehabilitation facility (OR 26.4, 95% CI 2.87–243.1) and documented dietary nonadherence on follow-up (OR 3.78, 95% CI 1.50–9.53). There was no difference in the median duration of postoperative antibiotic administration between patients that did and did not experience major complications (P = .922).

Major Complications, Multivariable Analysis

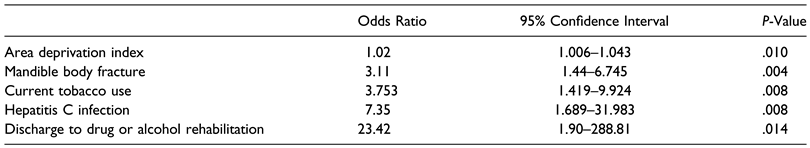

The statistically significant variables from univariable analysis were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. In this model, the following variables showed statistically significant associations with major complications: increasing Area Deprivation Index (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01– 1.04), mandible body fracture (OR 3.11, 95% CI 1.44–6.75), current tobacco use (OR 3.75, 95% CI 1.42–9.92), history of Hepatitis C infection (OR 7.35, 95% CI 1.69– 31.98), and discharge to drug or alcohol rehabilitation facility (OR 23.42, 95% CI 1.9–288.81). Multivariable logistic regression results are provided in

Table 1.

Minor Complications, Univariable Analysis

Preoperative Factors. The preoperative factors that were significantly associated with minor complications included a history of benzodiazepine use disorder (OR 10, 95% CI 2.35–42.55) and a diagnosis of schizophrenia (OR 2.92, 95% CI 1.032–8.26). Of note, eight patients had a history of benzodiazepine use disorder, and 18 patients carried a diagnosis of schizophrenia prior to hospital presentation.

There was no difference in the median preoperative antibiotic duration between those patients who did and did not experience minor complications (P = .63). Likewise, no difference in the time interval from injury to surgery was observed between these two groups (P = .61).

Operative Factors. Of the operative techniques implemented, the use of an upper tension band was associated with an increased rate of complication (OR 2.27, 95% CI 1.18–4.40), as was ORIF with MMF (OR 2.50, 95% CI 1.01–6.20). Conversely, matrix plating was protective (OR .28, 95% CI 0.106–.744), as was closed reduction with MMF (OR .332, .11–.97).

Perioperative and Postoperative Factors. On univariable analysis, postoperative factors associated with minor complications included discharge to the street (OR 17.03, 95% CI 1.73–167.8) and documentation of poor oral hygiene on follow-up visit (OR 11.59, 95% CI 2.10–65.44). Four patients were discharged to the street, and six patients had poor oral hygiene documented on follow-up.

There was no difference in the total antibiotic duration in patients who did and did not experience minor complications, respectively (P = .99).

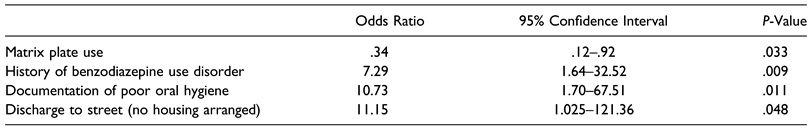

Minor Complications, Multivariable Analysis

A multivariable logistic regression model included factors found to be statistically significant on univariable analysis. The factors found on multivariable analysis to correlate with increased risk of minor complications included a history of benzodiazepine use disorder (OR 7.29, 95% CI 1.6–32.5), documented poor oral hygiene on follow-up (OR 10.73, 95% CI 1.7–67.5), and discharge to street (OR 11.15, 95% CI 1.03–121.4). Matrix plating was associated with reduced odds of minor complications, OR .298 (95% CI 0.11–.82). This multivariable analysis is provided in

Table 2.

Discussion

In this retrospective study of 272 patients with operatively managed mandible fractures, several trends in the sample speak to the challenges faced by this and similar communities. Substance use disorder and tobacco use were prevalent (57% and 62% of the cohort, respectively). These findings reflect existing data regarding the population served by this trauma center. Of those living in North Philadelphia, 25% carry a substance use disorder diagnosis, and 45% of patients live at incomes at or below 100% of the federal poverty line [

11].

Despite a relatively young median age of 33 years, our patients faced a disproportionately high medical and psychiatric comorbidity burden—46% of patients had at least one comorbidity. Assault was the predominant mechanism of injury, which reflects trends seen in prior studies of facial trauma patients in similar settings [

3,

4,

12,

13]. Additionally, 8.4% of our sample reported housing instability or homelessness, and 7.7% reported recent domestic violence. These demographics illustrate a significant psychosocial and medical risk burden within the study cohort.

The lessons learned from treating this distinct population provide valuable insight to trauma centers serving similar communities; however, a more expanded understanding of clinical and psychosocial risk factors can improve care for all patients treated for mandible fractures.

Due to the large range of complication severity seen in the sample, from small wound dehiscence to hardware failure, a complication was categorized as “major” if it required an unplanned return to the operating room and “minor” if not. This study reveals the critical risk factors associated with both major and minor complications and calls attention to risk factors that are often more prevalent and less well-resourced in socially vulnerable communities.

Variables associated with increased odds of major complications included Area Deprivation Index, current tobacco use, mandible body fracture, hepatitis C infection, and discharge to drug or alcohol rehabilitation center. Several notable factors were not significantly associated with an increased risk of major complications on univariable or multivariable analysis: there was no significant difference in the interval from injury to surgery, the median preoperative antibiotic duration, or operative technique between those patients that developed a major complication and those that did not.

These findings suggest that factors outside of the surgeon’s control, notably substance use and Area Deprivation Index (itself a surrogate marker for socioeconomic status), are more strongly associated with major complications than elements of clinical decision-making, such as operative technique and antibiotic use. As other authors have pointed out, a history of substance use disorder is frequently associated with postoperative infections related to inadequate follow-up, increased patient risk-taking behavior, and perhaps even changes in physiologic response to wound healing [

1,

8,

14].

Less modifiable than patients’ substance use is the home environment from which they present and to which they must return after discharge. This is the first study investigating mandible fracture complications in light of patients’ unique residential surroundings as represented by the Area Deprivation Index. The Area Deprivation Index provides a snapshot of the conditions in which patients convalesce after discharge from the hospital. It assesses, among other factors, the average income, education, and housing stability for a given neighborhood. Though it is an imperfect means of measuring socioeconomic status, it provides a valuable understanding of the hardships (financial and otherwise) many patients face in neighborhoods with higher ADI. Additionally, ADI has been utilized to highlight health disparities across various surgical and medical disciplines [

15,

16,

17]. In fact, a recent study of general surgery patients found that ADI scores independently predicted major postoperative complications. Each increasing ADI quartile was associated with an 11% increased risk of complications [

18].

It is worth noting that mandible body fracture location in this study was independently associated with an increased risk of major complications. On subgroup analysis, factors statistically associated with mandible body fractures included premorbid diabetes (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.05–7.0) and gunshot wounds as the mechanism of injury (OR 8.34, 95% CI 2.6–27.2). It is generally accepted that injuries sustained by gunshot wounds impart significant kinetic injury and often result in devastating injuries [

19]. It is possible that those patients who suffered these injuries were already predisposed to inadequate immune response and poor wound healing related to underlying diabetes. Nevertheless, mandible body fracture remained statistically correlated with major complications when comorbid medical conditions and mechanism of injury were controlled for in the multivariable analysis, suggesting that confounding alone does not explain this finding. There may be a unique interplay of the mandible body’s geometry, blood supply, and the violent forces required to disrupt it that may lead to higher rates of major complications. Additional investigation is needed to understand the connection between mandible body fracture and an increased risk of operative complications and to determine the replicability of this finding.

Minor complications, though requiring less intervention than major complications, add to the emotional and physical burden patients face after their initial injury and operative repair. This review of minor complications revealed several risk factors that could negatively affect patients’ postoperative course. Based on multivariable analysis, these risk factors included a history of benzodiazepine usage, documented poor oral hygiene on follow-up, poor oral hygiene on postoperative follow-up examination, and discharge to the street. The use of matrix plating (as opposed to miniplates, standard tension bands, and reconstruction bars) was associated with reduced odds of minor complications. The biological foundations underlying these findings are a matter of active research. However, it has been speculated that matrix miniplate fixation results in increased fracture stability, particularly in fractures of the mandible angle [

20]. These risk factors for minor complications (the majority of which were infectious) mirror those reported by other studies [

1,

2,

4,

8]. Inadequate discharge disposition in which unhoused patients were discharged back to the street and even poor hygiene at follow-up visits point to the unpredictable surroundings and poor access to resources that many patients experience following hospital discharge.

Recommended Approach for Postoperative Care

Considering the study findings and in keeping with our institutional mission, the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at our institution has sought solutions to improve the care patients receive after sustaining a mandible fracture. This approach utilizes a multidisciplinary team-based concept that emphasizes active patient engagement at each step.

First, this approach acknowledges the psychological effects of a traumatic injury, whether or not a patient has a pre-existing behavioral health disease diagnosis. All patients with mandible fractures are admitted to the Trauma Surgery service and are given the option to meet with dedicated trauma advocates. These peer specialists have experienced trauma and are trained to support others through the mental and emotional effects of traumatic injuries. Patients with premorbid behavioral health disease are referred to psychiatric services upon discharge, promoting continuity of care for their mental health needs. Patients with a history of substance use or tobacco use disorder, if amenable upon counseling, are referred to dedicated cessation programs. Finally, all patients meet with case management within 48 hours of admission, the goal of which is to address the financial, discharge disposition, and insurance-related problems patients may face to avoid future disruptions in care.

The most critical processes the team has introduced aim to facilitate frequent and adequate follow-up. Short-interval clinic appointments are scheduled for all patients prior to discharge. As has been discussed by Said et al., we have also leveraged the benefits of telehealth modalities; this convenient mode of follow-up reduces the logistic and financial burden of in-person visits and ensures that surgeons can monitor their patients’ progress on an ongoing, frequent basis [

21]. And finally, perhaps the smallest change with the biggest impact is saving the Plastic Surgery clinic information into patients’ cell phones before discharge. The benefit is multifactorial: first, patients can quickly contact the clinic if concerns arise between regularly scheduled visits. Additionally, when the clinic staff reaches out to patients, the phone number does not display as an unknown or blocked number on patients’ phones. It is our experience that patients are more likely to answer or return the phone call when they recognize the caller as part of their care team. These changes demonstrate to patients that the Plastic Surgery team is invested in their care and committed to seeing them through their recovery journey.