Abstract

Study Design: Retrospective cohort study. Objective: Frontal sinus fractures (FSFs) can lead to a range of clinical challenges, including facial deformity, impaired facial sensation, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage, sinus drainage impairment, chronic sinus pain and mucocele formation. The optimal management approach, whether surgical or conservative, remains a topic of ongoing discussion. The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the functional and esthetic outcomes of patients with surgically and conservatively treated FSFs. Methods: In this retrospective study, patients treated for FSFs at the Karolinska university hospital 2004 to 2020 were identified in hospital records and invited to participate in a long-term follow-up. Sequelae and satisfaction with the esthetic result were assessed trough questionnaires and physical examinations. Results: A total of 93 patients were included in the study, with 49 presenting isolated anterior wall fractures and 44 presenting combined anterior and posterior wall fractures. Surgical intervention was performed in 45 cases, while 48 were managed conservatively. Among patients with moderate anterior wall fractures (4–6 mm dislocation), 80% of surgically treated patients compared to 100% of conservatively treated patients expressed satisfactionwith their cosmetic outcomes at follow-up (p = 0.03). In conservatively treated patients with a forehead impression, the anterior wall fracture dislocation ranged from 5.3 to 6.0 mm (p < 0.0001). Approximately 50% of surgically treated patients vs. 15% of conservatively treated patients developed impaired forehead sensation at follow-up (p = 0.03). Thirty-six percent of surgically treated patients reported dissatisfaction with surgery-related scarring, particularly those who underwent surgery via laceration or bicoronal incision. Conclusions: This study suggests that anterior FSFs with a dislocation of 5 mm or less can be effectively managed conservatively with high patient satisfaction, low risk of long-term forehead sensation impairment and without potential development of forehead impression. Bicoronal incision or incision via a laceration may be associated with esthetic dissatisfaction and late sequelae such as alopecia.

Background

Frontal sinus fractures (FSFs) are relatively uncommon fractures that account for 5–15% of all craniofacial fractures [1,2,3,4,5]. In most cases, these fractures result from high-energy trauma such as physical violence, traffic accidents, or sporting events [3,4,6]. FSFs may cause facial deformity, CSF leakage, sinus drainage impairment, long-term sinus pain, sinonasal mucocele, impaired facial sensation, and impaired olfaction [1,3,4,7,8,9,10].

Approximately 33–50% of FSFs are isolated anterior wall fractures [3,4,8,9]. Combined anterior and posterior wall fractures are seen in 30–67% of cases and are generally related to high-energy trauma [4,5,11], while isolated posterior wall fractures are very uncommon [3,11]. In approximately 30% of cases, the frontal sinus outflow tract (FSOT) is involved, which may result in impaired sinus function if not treated appropriately [3,9,12,13,14].

The management of FSFs has evolved over the last decades. Traditionally, isolated anterior wall fractures have been treated with open reduction and internal fixation, fractures involving the FSOT with sinus obliteration, and fractures involving the posterior wall with cranialization [2,3,4,9,11,15,16]. A common approach for all these surgeries has been the use of the bicoronal incision. However, this approach is associated with risks and late sequelae such as visible scarring, alopecia, temporal hollowing, scalp necrosis, and facial nerve injury [4,5,7,17,18,19]. The drawbacks of the bicoronal incision, and a general trend toward minimal invasive surgery, have led to the development of new approaches to treating FSFs such as the supra brow approach, the sub-brow approach, the supra tarsal approach, the endoscopic brow approach, and percutaneous reduction techniques [5,6,12,17].

Few studies have investigated the correlation between the degree of dislocation of anterior wall fractures and the need for surgery. Kim et al. [8] and Dalla Torre et al. [12] have suggested that isolated anterior wall fractures with displacement <4 mm and <5 mm, respectively, may be treated conservatively without risk for cosmetic sequelae (forehead asymmetry), while other authors have recommended surgery if the fracture displacement is 2-5 mm or more [2,3,8,9,11,12].

‘Wait and see’ strategies have also evolved, with surgery performed as a delayed secondary camouflage procedure if needed due to unsatisfactory cosmetic results [12,20].

Given the different and sometimes conflicting recommendations, it is still challenging to decide whether an FSF requires surgery [8,11,12,21]. With a lack of robust evidencebased guidelines, the decision between surgery and conservative treatment is often based on the surgeon’s previous experience. A wider understanding of the long-term esthetic and functional outcome of surgically or conservatively treated FSFs may help the clinician in the decision-making process. The aim of this study was to evaluate the esthetic and functional outcome of either surgically or conservatively treated FSFs, with the aspect on the anterior wall, over a period of 16 years. Both the patient’s and the physician’s assessments of the outcome were evaluated.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

This was a retrospective cohort study on the outcome of patients with FSFs treated at Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm in Sweden from 2004 to 2020. Since FSFs do not have a unique ICD-10 code, eligible subjects were identified from the hospital records through a review based on the following ICD codes: S020, S027, S0270, S0271, S028, S0280, S0281, S029, S0290, and S0291, followed by a screening of individual medical records. To be included, subjects had to be 18 years or older at the date of the review of the medical records, had to be 15 years or older at the time of injury, and had to have received at least one year of follow-up time after the injury. Subjects with a history of cosmetic surgery in the forehead region after the primary injury or an FSF before 2004 were also excluded. Surgically treated patients without recorded postoperative CT scans were excluded. One patient who had been treated surgically and had a recorded postoperative infection leading to reoperation and medical treatment was excluded.

From checking approximately 3000 screened patient records, it was found that 284 patients had been treated for FSF, of which 258 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and were kept in the final data set.

Data Collection

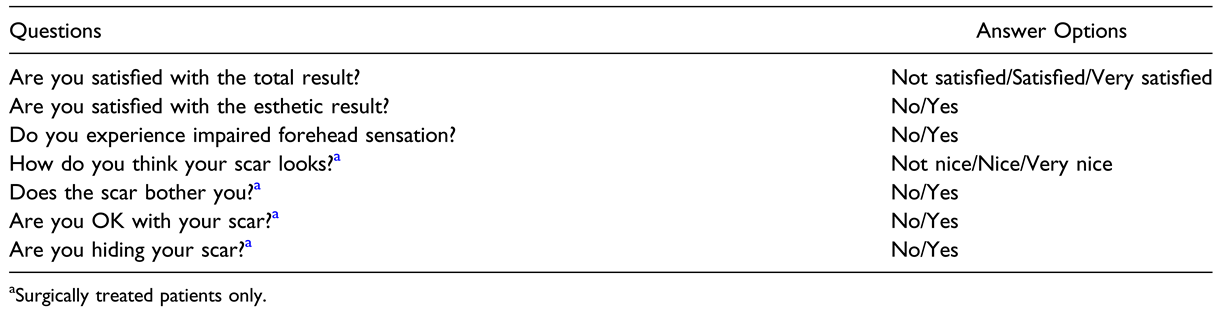

Eligible subjects were informed about the study by mail, and two weeks later were called on the phone (on at least three different occasions) for consent and to schedule an appointment for the follow-up data collection. Before the appointment and to avoid biased responses, the subjects answered a questionnaire regarding their current symptoms and whether they were satisfied with the overall and esthetic outcome of the treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Patient Questionnaire Used in the Study.

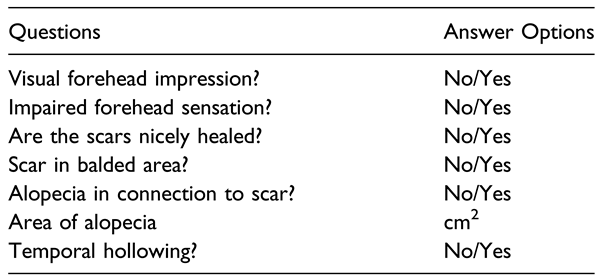

All subjects were physically examined according to a standardized protocol (Table 2) including inspection and palpation of the facial skeleton, assessment of facial sensation by digital touching, and examination of scars from surgery. The area of injury and scars related to surgery were photographed. Alopecia related to scars was noted, assessed, and photographed. The type of trauma, time from trauma to surgery, and follow-up time were noted.

Table 2.

The Physician Assessment Protocol.

Data on age, gender and type of fracture were collected from the medical records. CT scans from the time of injury, and for surgically treated patients also postoperative CT scans, were examined. The maximum fracture dislocation before surgery and residual dislocation after surgery (when applicable) were determined by a close examination of the fracture area on axial CT slices. The dislocation was measured from the point of maximum fracture depth (mm, one decimal) to an estimated pre-injury forehead line (the estimation was based on the contralateral and unaffected forehead line).

All participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden (2021-01410).

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]) or percentages as appropriate. Statistical significance was set at the level of p < 0.05. Comparisons between two groups were performed using the non-parametric Wilcoxon test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for nominal variables. Comparisons between three groups were performed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for nominal variables. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the predictors of the cause of injury. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Software Stata 17.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Out of the 258 patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 136 (53%) were contacted by phone. Of these, 34 declined participation and another nine did not attend the scheduled follow-up appointment. Thus, 93 of the 258 eligible patients (36%) attended the follow-up and were included in the study.

Main Characteristics of the Studied Population

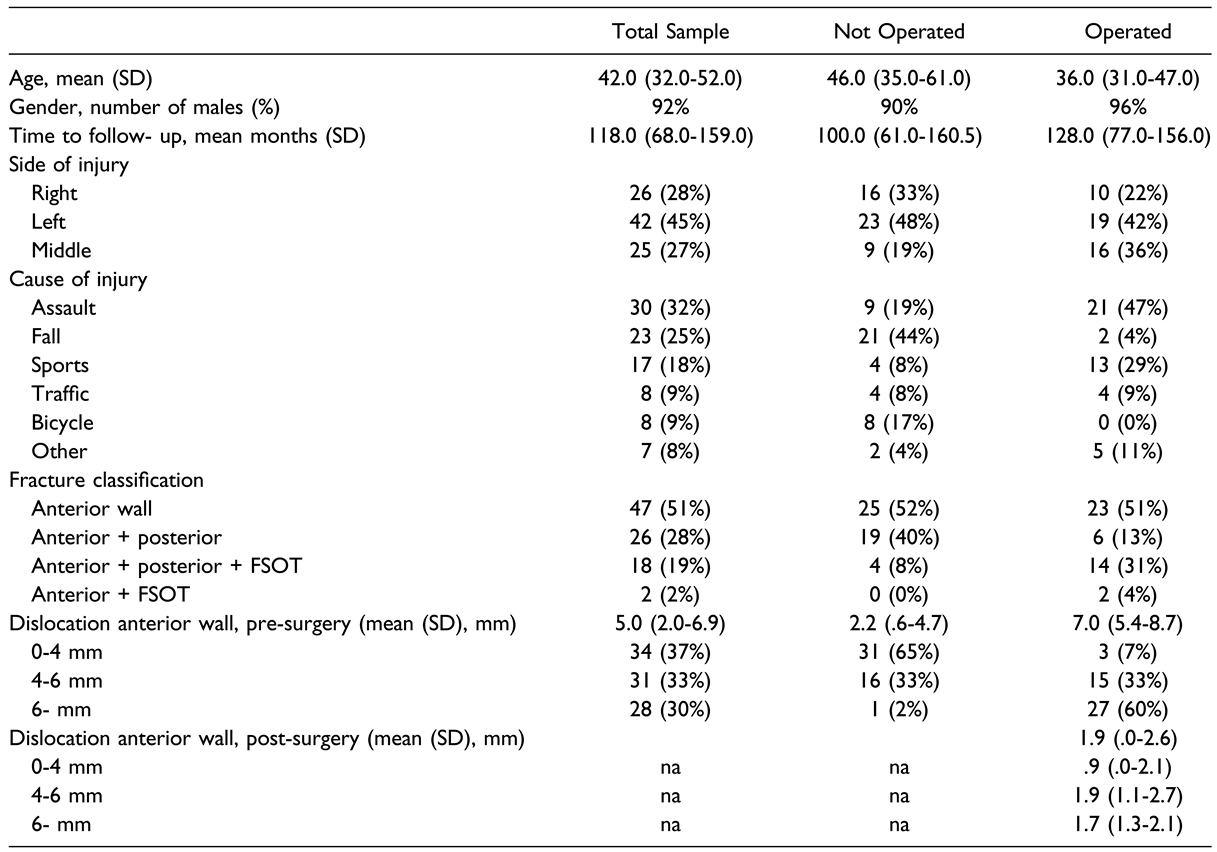

The median age in the operated group was 36 years and in the non-operated group 46 years. In total, seven patients were female, whereas 86 patients were male. The median follow-up time from injury to study inclusion was 118 (68–159 (SD)) months (approximately 10 years) (Table 3).

Table 3.

General Characteristics of the Studied Population and Type of Fractures.

Forty-nine of the patients (53%) had an isolated anterior wall fracture and 44 (47%) had a combined anterior and posterior wall fracture. Twenty patients (22%) had a fracture involving the FSOT, 18/20 with a combined fracture, and 2/20 with an isolated anterior wall fracture.

The most common cause of injury was physical violence (32%), fall (25%), sports activities (18%), and traffic and bicycle accidents (9%). Notably, physical violence was a more common cause of injury in the surgically treated group (21/45 patients; 47%), whereas a fall was more common in the conservatively treated group (21/48; 44%) (Table 3). Patients with physical violence or sporting events as the cause of injury were significantly younger than patients with a fall or bicycle accidents as the cause of injury (p < 0.05).

A total of 45 patients (48%) had been treated surgically, and 48 patients (52%) conservatively.

There were no clear guidelines regarding indication for surgery during the study period. Our interpretation of the information in the medical records is that the main criteria for surgical vs. conservative treatment was the degree of fracture dislocation of the anterior wall (ie, the risk for residual forehead asymmetry). All patients with a dislocation over six mm (except from one patient who declined surgery) underwent surgery.

Outcome

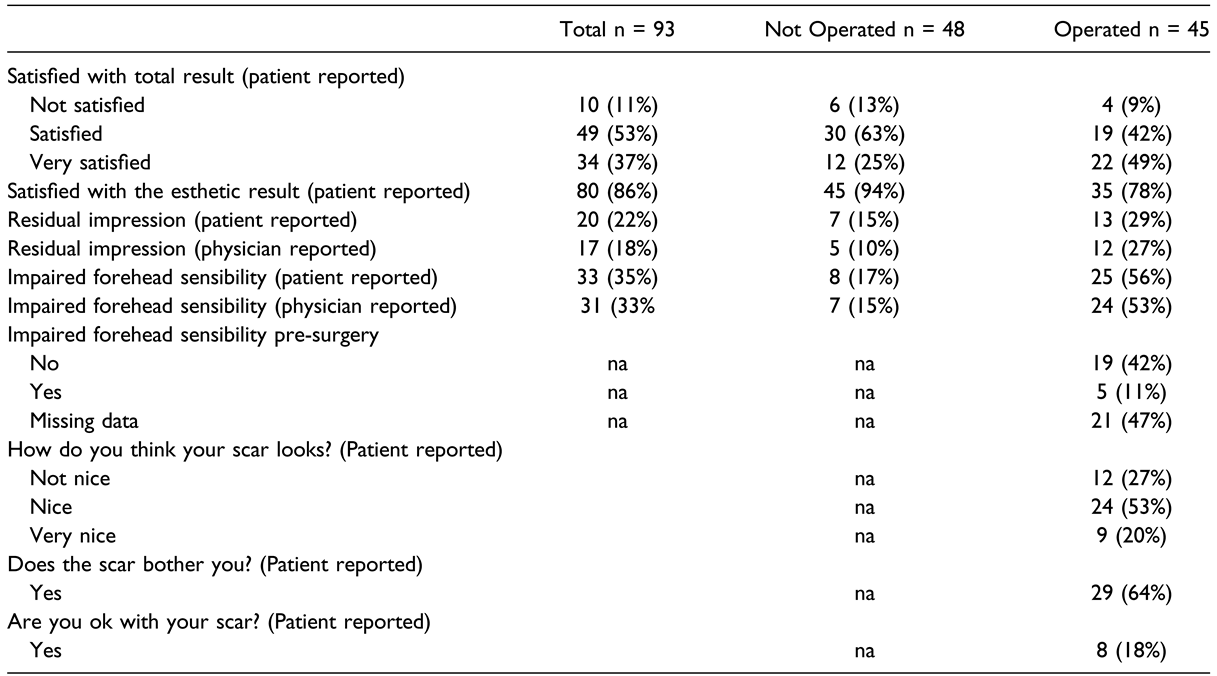

Most patients (89%) reported that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the overall outcome. However, 22% of patients in the surgically treated group and 6% of patients in the conservatively treated group were dissatisfied with the esthetic outcome of their treatment at follow-up.

Self-reported impaired forehead sensation was found among 56% of patients in the surgically treated group (n = 25) and 17% in the conservatively treated group (n = 8) while physician-reported impaired forehead sensation (supraorbital nerve area) was noted in 52% (n = 23) and 15% (n = 7) respectively (Table 4). Forehead sensation before surgery was assessed and found to be normal in 19 (42%), and impaired in 5 (11%), of the 45 operated patients. In the remaining 47% of cases in the surgically treated group, no information was found in the patient records to indicate whether the forehead sensation had been tested before surgery or not.

Table 4.

Outcome.

The median fracture dislocation of the anterior wall (before surgery) was 7.0 (5.4–8.7) mm in the surgically treated group, 2.2 (0.6–4.7) mm in the conservatively treated group, and 5.0 (2.0–6.9) mm overall. The fractures were divided into mild (0–4 mm), moderate (4–6 mm) or severe (>6 mm). Sixty percent of surgically treated fractures were severe and 65% of conservatively treated fractures were mild. Thirty-three percent of surgically treated and 33% of conservatively treated fractures were moderate. The mean residual dislocation of the anterior wall after surgery was 1.9 mm (0.0–2.6) (Table 3).

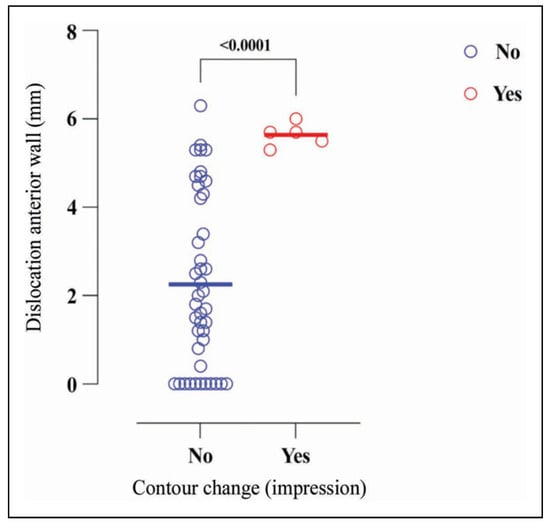

The physician-reported visible forehead impression was observed at follow-up for 27% of the surgically treated patients (12/45) and 10% of the conservatively treated patients (5/48).

Among these five conservatively treated patients with a visible forehead impression at follow-up, the dislocation of the anterior wall fracture (measured on CT) ranged from 5.3 to 6.0 mm (p < 0.0001; Figure 1). Furthermore, five patients in the conservatively treated group without a visible forehead impression at follow-up had a fracture with dislocation >5 mm (5.3 mm for three subjects, and 5.4 mm and 6.3 mm for two subjects respectively). The correlation between dislocation on CT and subjective physician-reported forehead impression was good with a significant cut-off value of 5.3 mm, under which no forehead impression could be seen in the conservatively treated group. One subject in the conservatively treated group had a fracture dislocation >6 mm but no visible forehead impression (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Residual forehead contour change at follow-up among conservatively treated patients.

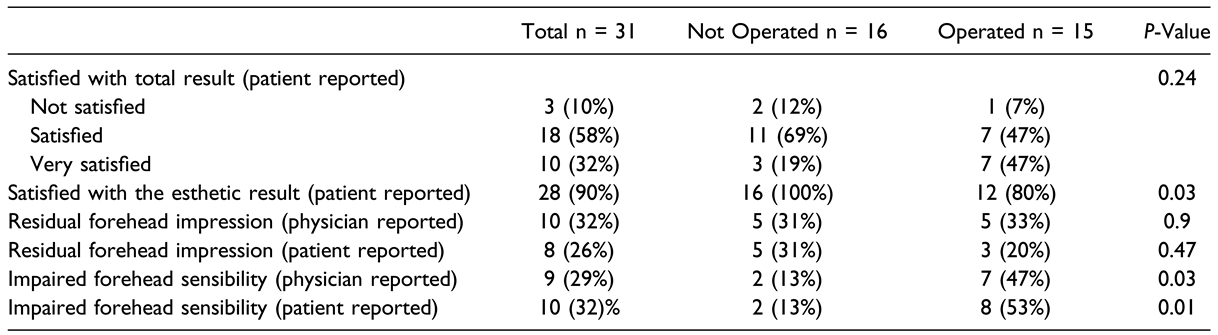

Sub-Analysis Among Anterior Wall Fractures with Moderate Dislocation

As mentioned, 31 patients (33%) presented with an anterior wall fracture (isolated or combined) with moderate dislocation (4-6 mm) (Table 5). As 15 (48%) of these had been treated surgically and 16 (52%) conservatively, a sub-analysis of these similar groups was made. Eighty percent of the surgically treated patients (12/15) vs. 100% (16) of the conservatively treated patients in this group reported that they were satisfied with the cosmetic results of the treatment (p = 0.03).

Table 5.

Sub Analysis Comparing Surgically and Conservatively Treated Patients With Moderate Dislocation of the Anterior Wall (4–6 mm).

Impaired forehead sensation (supraorbital nerve area) was significantly more common in the surgically treated group (47%) compared to the conservatively treated group (13%) (physician-reported) (p = 0.03). No difference concerning residual forehead impression after the injury could be seen comparing surgically or conservatively treated patients with moderate dislocation of the anterior wall (physician- and patient-reported, p = 0.9 and 0.47, respectively).

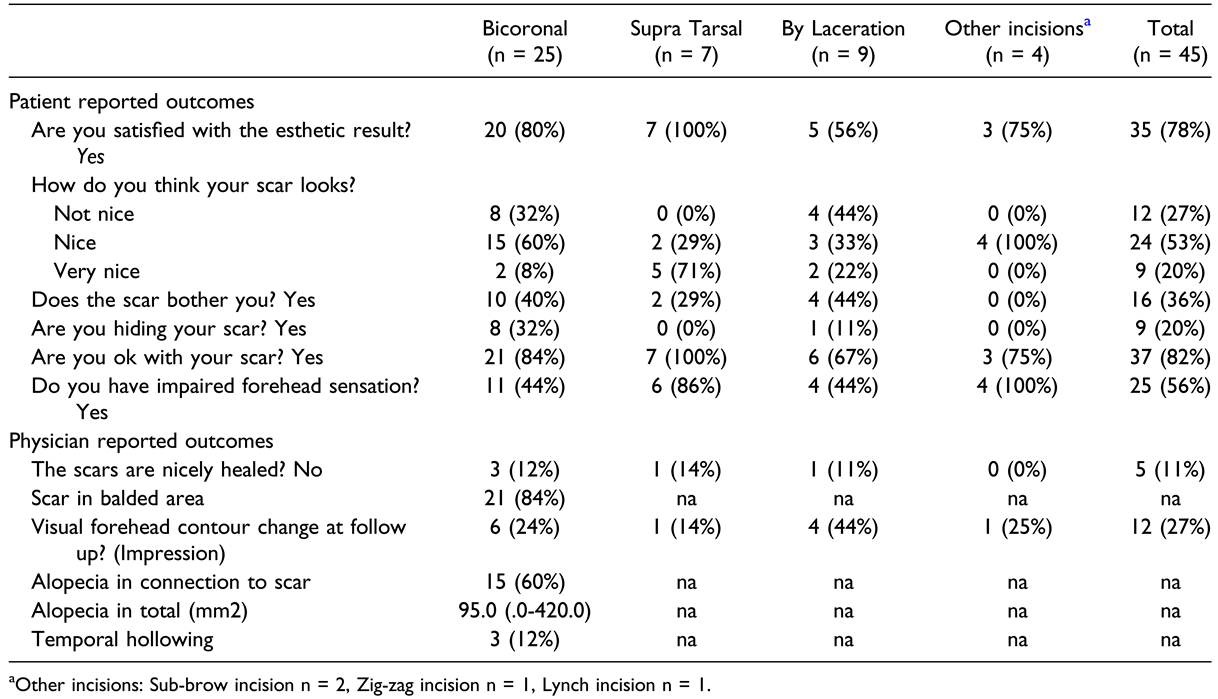

Results in the Surgically Treated Group

Among the 45 surgically treated patients the three most commonly used incisions were the bicoronal incision (n = 25), incision via an existing laceration (n = 9) and the supratarsal incision (n = 7) (Table 6). Twelve of the surgically treated patients (n = 45) showed a residual visible forehead impression (physician-reported) at follow-up; six of them had been operated with a bicoronal incision, four of them through an existing laceration, one of them through a supratarsal incision and another one through a sub-brow incision Table 6). The mean residual dislocation of the anterior wall among these 12 patients was 2.0 mm (0.0–2.7 mm). Notably, 11 of these 12 patients had a residual dislocation between 0.0–3.2 mm, whereas one patient (operated with a supratarsal incision) had a residual dislocation of 5.4 mm.

Table 6.

Outcome in Relation to Incision in Surgically Treated Patients.

Twenty-seven percent of surgically treated patients reported that their surgical scar did not look nice, and 36% that the scar bothered them. In addition, 44% (4/9) of patients operated via an existing laceration and 32% (8/25) operated with a bicoronal incision reported that their surgical scar did not look nice. This opinion was not reported by any of the patients operated with a supratarsal incision or other incisions (sub-brow incision [n = 2], Lynch incision (medial orbit incision) [n = 1], and zigzag incision [n = 1]; p = 0.007; Table 6).

In comparison, 89% of surgical scars (n = 40) were noted to be nicely healed when examined by the physician. Among the five patients with surgical scars that were not nicely healed (according to the physician) only one patient had self-reported dissatisfaction regarding the esthetic results of their surgical scar.

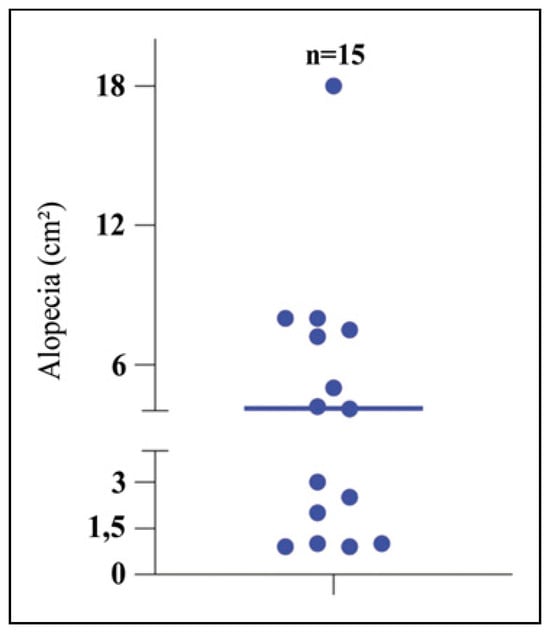

Among patients operated with a bicoronal incision, 60% had developed alopecia (n = 15), 12% exhibited temporal hollowing, and 56% experienced impaired sensation in connection with the surgical scar at follow-up (Table 6).

Among the 15 patients with alopecia, the area of alopecia ranged from 0.9 to 18 cm2, with a mean value of approximately 5 cm2 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Alopecia after bicoronal surgery.

Discussion

In this long-term follow-up study, we evaluated patient satisfaction and the esthetic and functional outcomes in individuals with FSFs treated either surgically or conservatively with the aspect on the anterior wall. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind to focus on patient satisfaction. We found that surgically treated patients, when comparing moderate fractures only but also when looking at all fractures, were more often dissatisfied with the esthetic outcome in comparison to conservatively treated patients, and that 36% of all surgically treated patients were bothered by their surgical scar. We noted that a bicoronal incision and an incision via an existing laceration were associated with more potential esthetic dissatisfaction compared to a supratarsal incision, which showed no such risk in the present study. We also observed that the development of alopecia and temporal hollowing after surgery using the bicoronal approach was slightly higher in the present study than in other studies [22,23]. This may be explained by the long follow-up time in this study (mean approx. 10 years), possibly making it more likely for soft tissue damage or alopecia to develop over time. However, it is hard to compare and draw conclusions about the incision types since the groups are small and also because different incisions may have to be used depending on the specific fracture from different trauma situations.

In the present study, surgically treated patients had a higher proportion of persistent impairment of forehead sensation than conservatively treated patients, both when comparing the similar moderate fracture group only and when looking at all fractures. No significant differences were observed between the different incision techniques. Most examined patients had normal forehead sensation before surgery, suggesting that surgery, irrespective of the kind of incision made, is associated with a risk of impaired forehead sensation.

Remarkably, a visible forehead impression at follow-up was more common in the surgically treated group compared to the conservatively treated group. This could not be seen when comparing surgically and conservatively treated patients in the moderately dislocated group. As mentioned in the results, the actual remaining fracture dislocation after surgery in the surgically treated group was markedly less than the cut-off value for dislocation of the anterior wall with no potential risk of forehead impression in the conservatively treated group (<5 mm). This indicates that factors other than residual fracture dislocation may lead to forehead asymmetry in the surgically treated group scar deformity or soft tissue defects, potentially as a result of surgical dissection, may explain the forehead asymmetry because residual forehead impression was more commonly observed among patients operated via an existing laceration or bicoronally.

Furthermore, 44% of patients operated via an existing laceration reported esthetic dissatisfaction with their scar. To reduce the rate of dissatisfaction, we suggest informing patients with open fractures thoroughly to help them achieve realistic esthetic expectations before surgery via an existing laceration. If the laceration is superficial it may be preferable to make an alternative more subtle incision and not to make incisions in deeper, intact soft tissues.

When analyzing only the moderate fracture group (4–6 mm), all of the conservatively treated patients were satisfied with the cosmetic results of their injury whereas 20% of the surgically treated patients were dissatisfied. In addition, the surgically treated patients in this group had a significantly higher risk for future impaired forehead sensation. We could not see any difference concerning forehead impression between surgically and conservatively treated patients with moderate dislocation of the anterior wall. Looking at all the conservatively treated patients in the study (n = 48), we could not see a forehead impression among any of the patients with a fracture dislocation of 5.2 mm or less. All together, and in line with other authors [5,8,12] we suggest a more conservative approach when treating anterior FSFs than has been described earlier [3].

In this study we noted a good correlation when comparing the patients’ and the physician’s answers concerning impaired forehead sensation and forehead contour change (impression) at follow-up. However, this correlation was much lower when comparing patients’ and physician’s answers concerning the esthetic results of their surgery scars. Only in one of the 12 cases when patients reported dissatisfaction with the surgery scar were the answers correlated to the physician’s assessment.

Consistent with the findings of Strong et al. and Adetokunbo et al., we observed a lower rate of traffic-related causes of trauma than that reported historically, most likely explained by the development of safer vehicles in general [3,4,11,18,19]. Furthermore, we noted that older patients were more often treated conservatively and were more likely to have falls or bicycle accidents as the trauma type, whereas younger patients were more often treated surgically and had a fracture resulting from physical violence or sporting events.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study has certain limitations. It was difficult to make contact with and include potential research subjects. Because of this dropout we could include only a relatively small group of 93 patients. The patients’ and physicians’ questionnaires used in this study were designed by our team (not validated). No definition of “nicely healed” was used when examining surgically treated patients’ scars and furthermore, we did not ask conservatively treated patients about their experience of any scarring after their treatment. Because this was a retrospective study, there was a significant selection bias regarding whether patients were treated surgically or conservatively.

The strengths of this study are the relatively long median follow-up time, and that all patients were examined by the same examiner.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that anterior frontal sinus wall fractures with a dislocation of 5 mm or less can be treated conservatively with great patient satisfaction and without the potential development of a forehead contour impression.

Surgical treatment of FSFs, irrespective of the kind of incision made, poses a considerable risk for persistent impairment of forehead sensation. The correlation between physician-reported and patient-reported answers seems to be good but not when it comes to the assessment of surgery scars.

We noted that bicoronal incisions or incisions via existing lacerations may be associated with esthetic dissatisfaction of patients and late sequelae such as alopecia, forehead asymmetry and temporal hollowing. If possible, surgeons might consider alternative incisions when treating FSFs surgically.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Firouzbakht, P.K.; Mohiuddin, I.S.; Varman, R.M.; Heinrich, M.P.; Saa, L.; Cordero, J. Analysis of frontal sinus fracture management and resource utilization. J Craniofac Surg. 2020, 31, 2240–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echo, A.; Troy, J.; Hollier, L. Frontal sinus fractures. Semin Plast Surg. 2010, 24, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strong, E.B. Frontal sinus fractures: Current concepts. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Reconstr. 2009, 2, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, A.; Donald, P.J. Frontal sinus fractures: A review of 72 cases. Laryngoscope. 1988, 98, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obayemi, A.; Losenegger, T.; Long, S.; et al. Frontal sinus fractures: 10-year contemporary experience at a level 1 urban trauma center. J Craniofac Surg. 2021, 32, 1376–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.S.; Rhee, J.S. Frontal sinus and naso-orbital-ethmoid fractures. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2014, 16, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, H.M.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, M.C.; Lee, I.J.; Kim, S.M.; Park, D.H. Reduction of closed frontal sinus fractures through suprabrow approach. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017, 18, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Yoon, E.S.; Lee, B.I.; Dhong, E.S.; Park, S.H. Fracture depth and delayed contour deformity in frontal sinus anterior wall fracture. J Craniofac Surg. 2012, 23, 991–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolino, P.; Vetrano, S.; Mundula, P.; di Lella, G.; Tedaldi, M.; Poladas, G. Frontal bone fractures: New technique of closed reduction. J Craniofac Surg. 2007, 18, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, E.E.; Glikson, E.; Shoshani, Y.; Dobriyan, A.; Yahalom, R.; Yakirevitch, A. Repair of frontal sinus fractures: Clinical and radiological long-term outcomes. J Laryngol Otol. 2021, 135, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshal, S.G.; Dedhia, R.D.; Strong, E.B. Frontal sinus fractures: A contemporary approach in the endoscopic era. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2022, 30, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Torre, D.; Burtscher, D.; Kloss-Brandstätter, A.; Rasse, M.; Kloss, F. Management of frontal sinus fractures treatment decision based on metric dislocation extent. J Cranio-Maxillo-Fac Surg. 2014, 42, 1515–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, E.M.; Jacobs, J.B.; Holliday, R.A. Evaluation of the frontonasal duct in frontal sinus fractures. Head Neck. 1989, 11, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, B.K. Approach to frontal sinus outflow tract injury. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2017, 18, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Morse, J.C.; Chandra, R.K. Is there still a role for cranialization in modern sinus surgery? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020, 29, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, E.D.; Stanwix, M.G.; Nam, A.J.; et al. Twenty-six-year experience treating frontal sinus fractures: A novel algorithm based on anatomical fracture pattern and failure of conventional techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008, 122, 1850–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinasab, B.; Fridman-Bengtsson, O.; Sunnergren, O.; Stjärne, P. The supratarsal approach for correction of anterior frontal bone fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2018, 29, 1906–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, T.; Salman, S. An aesthetic approach in the repair of anterior frontal sinus fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016, 45, 1104–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strong, E.B.; Pahlavan, N.; Saito, D. Frontal sinus fractures: A 28-year retrospective review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006, 135, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Rao, N.; Mohan, K; et al. Minimizing complications associated with coronal approach by application of various modifications in surgical technique for treating facial trauma: A prospective study. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2016, 7, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichova, H.; Chiu, A.G.; Villwock, J.A. Does the frontal sinus need to be obliterated following fracture with frontal sinus outflow tract injury? Laryngoscope. 2017, 127, 1967–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadakia, S.; Badhey, A.; Ashai, S.; Lee, T.S.; Ducic, Y. Alopecia following bicoronal incisions. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017, 19, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.H.; Kwon, H.; Kim, S.W. Cryptogenic temporal hollowing. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2016, 17, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2024 by the author. The Author(s) 2024.