Orthognathic surgery is commonly done in the United State with over 10,000 cases performed yearly [

1]. It is safe and has a relatively low rate of complications. Infections are one of the more frequent complications that can occur and may following operations of either the maxilla or mandible [

2]. The incidence of infection following a bilateral sagittal split may be as high as 10% [

3]. Fortunately, the majority of these are minor, usually secondary to local factors such as hematoma, seroma, or wound dehiscence [

3]. They usually present within the first 2–3 weeks after surgery and are routinely resolved with an intraoral incision and drainage and oral antibiotic therapy [

3,

4]. Secondary procedures may involve removal of plates placed at the osteotomy site [

3].

Rarely infections can progress to osteomyelitis [

5,

6]. One study found an incidence of 2 patients out of 1264 (.2%) of osteomyelitis in orthognathic patients [

5]. The initial presentation is similar to that found when local factors are an issue [

6]. Likewise the time line is similar to a local infection with vestibular fullness and purulence appearing 2 weeks after surgery [

6]. However, the infection fails to routine measures and progresses to osteomyelitis.

Even more uncommon is an infection caused by actinomycosis following orthognathic surgery. Actinomycosis is a component of the normal oral flora and may evolve into cervicofacial infection with disruption oral mucosa [

7]. Reports of actinomycosis infection following intraoral procedures have been reported including the removal of third molars [

8,

9]. While cervicofacial actinomycosis has been discussed in the literature there are only 3 studies with reported cases of actinomycosis following orthognathic surgery [

10,

11,

12]. The most recent of these reports was published in 2002 [

12]. Given the rarity and uncommon presentation of this entity, we plan to add an additional case and compare its course with those reported in literature. Emphasis will be placed on how this type of infection differs from the more routine types of infection that occur following orthognathic surgery.

Case Report

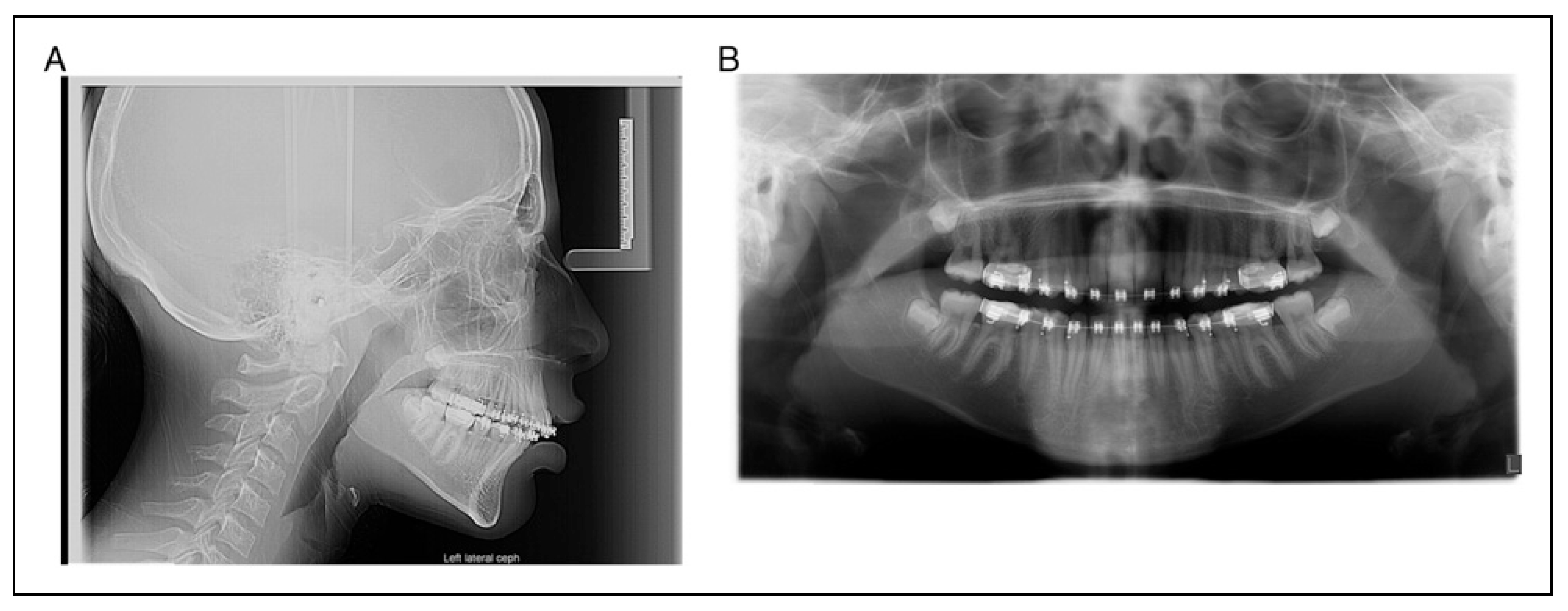

A 17-year-old woman presented for evaluation and treatment of mandibular hypoplasia (

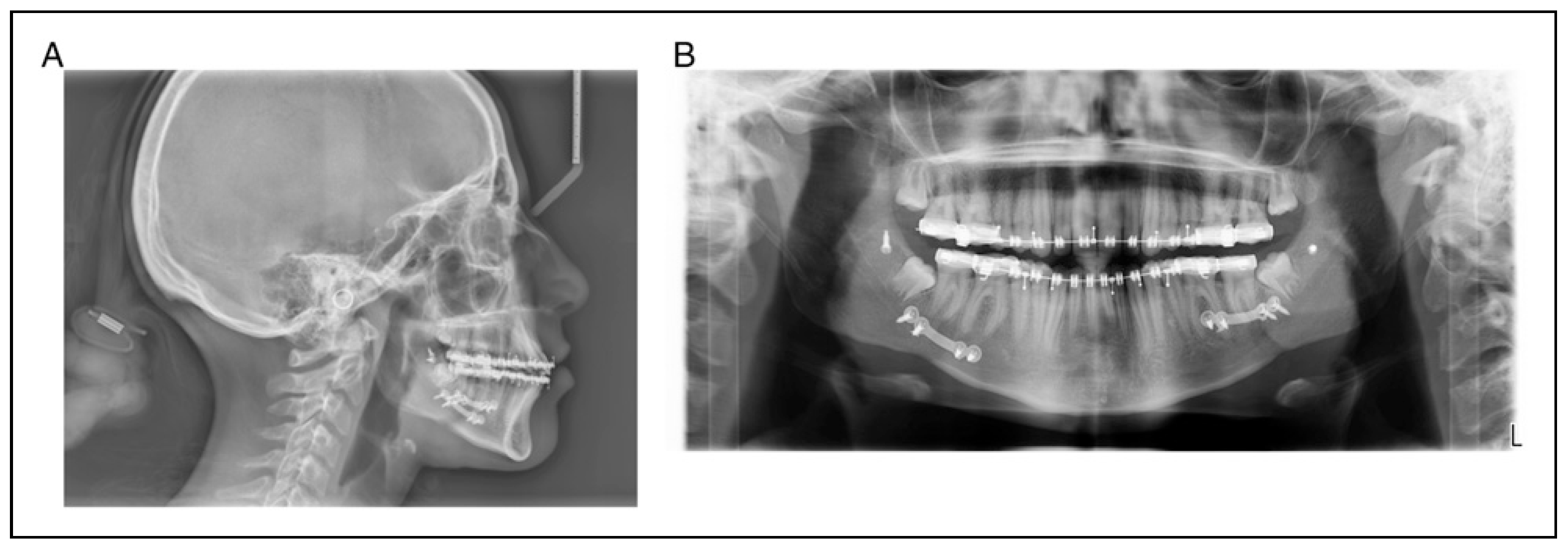

Figure 1A and 1B). Her medical history was significant for type I diabetes mellitus with an A1C of 8.1 one week prior to surgery. Her only prior surgery was tonsillectomy as a young child from which she recovered without issue. Her social history of negative for tobacco, alcohol, and drug use (smoking, vaping, use of tobacco of any kind). She received 1 g of cefazolin prior to incision. A bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (BSSO) was performed without intraoperative complication. Her lower third molars were not visualized during the surgery and were left in place. It was felt that removing them would lead to an unplanned fracture of the distal segment and that they would be removed at a later date. The mandible was fixed with a single 4-hole mono-cortical miniplate as well as 1 posterior bicortical screw bilaterally (

Figure 2A and 2B). Her postoperative course was benign. She was admitted for 23-h observation during which time she received 2 doses of 3 g of Unasyn. She tolerated a clear liquid diet; postoperative radiographs were obtained (

Figure 2A and 2B).

She was discharged on a 5-day course of Augmentin and seen at 1 and 2 weeks follow-ups without issue. She missed an appointment at 1 month following surgery but on a subsequent visit reported no issues at the time.

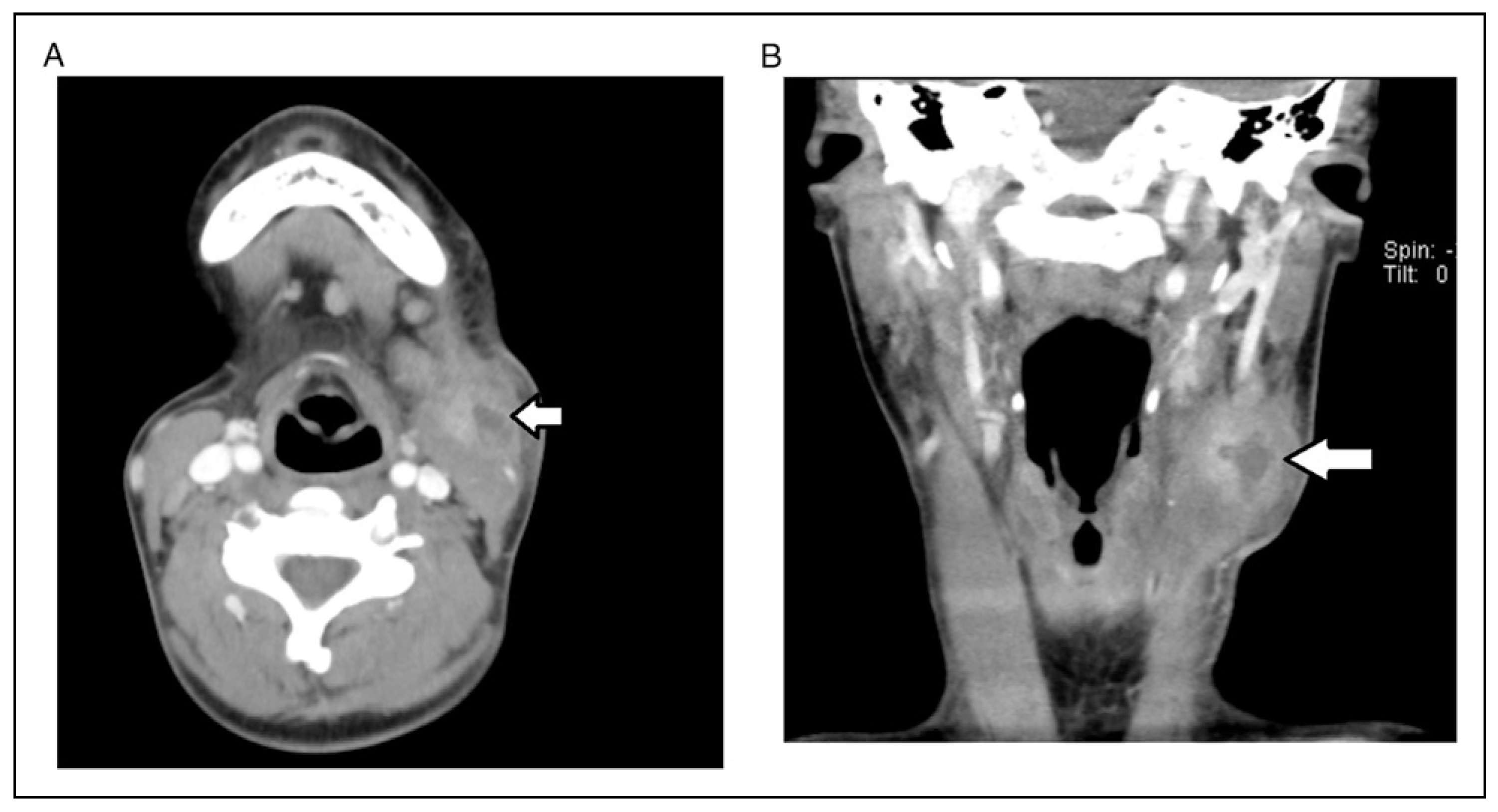

Four months after surgery, she presented with pain and fluctuance noted intraorally in the left mandibular vestibule. An incision and drainage was performed in the clinic under local anesthesia. Purulence expressed from the wound and was cultured. (Cultures were positive for normal oral flora. Actinomycosis was not seen.) The patient was given a 1-week course of Augmentin. The patient followed up a week later and was improving but her swelling and pain were not completely resolved. She was prescribed an additional week of Augmentin. She had resolution of symptoms when seen for follow up 3 weeks after her initial onset of symptoms. However, slightly over 1 month later (5 months after her BSSO) the patient re-presented with painful swelling on her left neck. Specifically, the swelling was along the anterior border of the SCM. In addition, she had a firm swelling along her left mandibular body. On examination, she was tender and warm over both sites, but these was no change in color to the skin. It was thought to be possible that she had a reactive or necrotic lymph node along her SCM. She was started on Bactrim as the previous intraoral culture taken grew Staphylococcus Aureus that was penicillin resistant but oxacillin sensitive. Three days later her symptoms and swelling had markedly increased prompting the need for hospitalization (

Figure 3).

On admission her WBC was 6.6 and her A1C was 7.9 She was started on Unasyn without resolution or worsening of symptoms. CT of the neck with contrast showed a multiloculated abscess superficial to the SCM muscle as well as an abscess superficial to the mylohyoid muscle in the left submandibular region. Interventional radiology was consulted to see if they could aspirate the lesion to get a culture. They performed an ultrasound guided aspiration of the lesion; however, no growth resulted from their aspirate. Clinically, there was minimal change in her findings.

She was then taken to the operating room for an extraoral incision and drainage 4 days after admission. The discharges from the abscess sites both in the neck and body of the mandible were noted to be thin and runny with small flecks of solid material in them. Aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal cultures were sent from both abscesses. Infectious Disease was consulted for assistance in management of the patient as the patient’s course of treatment varied from the usual presentation for an infection. The patient was continued on Unasyn; clindamycin was added to her treatment regimen. Following surgery, the patient clinically improved with reduction in pain and swelling. Her WBC decreased to 6.2 following surgery. During her hospitalization, her point of care glucose readings varied between 102 and 341. There was difficulty maintaining consistent glucose levels less than 180 due to dietary issues. She was discharged prior to final culture results on a regimen of oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875/125 BID and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim 800/160 for an anticipated course of 6 months due to concern of possible osteomyelitis and actinomycosis. Five days after the cultures were taken Actinomycosis Georgiae was identified using MALDI mass spectrometry. On day seven following the incision and drainage in the operating room, Prevatella Oris was isolated from the cultures. The patient was treated for a total of 6 months with this antibiotic regimen. Her surgical sites are healed without any signs of recurrence of infection. Her plates from her BSSO surgery are in place without sign of soft or hard tissue infection. At 9 months after surgery and off antibiotics for 3 months, she shows no signs of recurrent infection.

Literature Review

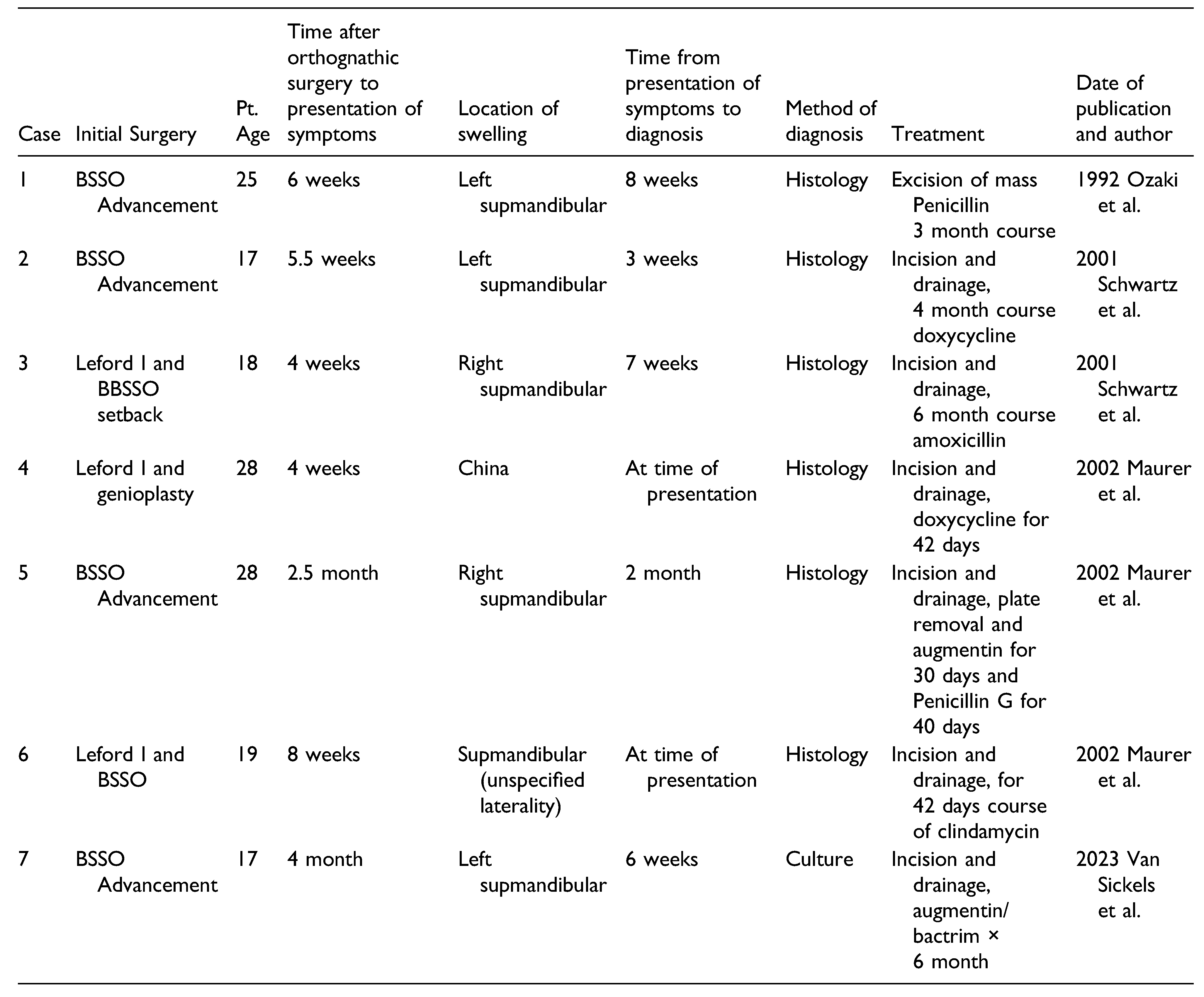

Our case is the 7th reported case of actinomycosis infection in an orthognathic surgery patient. The first published case was in 1992 by Ozaki et al. [

10] They identified Actinomycosis in a patient who underwent BSSO for mandibular deficiency [

10]. Like our patient, they describe an uneventful mandibular advancement in a 25-year-old patient. Six weeks after surgery, a left submandibular mass developed. The patient was admitted to the hospital and given IV penicillin G for 8 days with resolution of the mass. The patient was then discharged with 10 days of oral penicillin. 6 weeks after discharge the mass returned and began to increase in size. The mass was excised, and cultures and histology were obtained. Cultures were negative; however, histology with Brown and Brenn stain showed organisms consistent with actinomycosis. The patient completed a 3-month course of penicillin with complete resolution of symptoms.

In 2001, Schwartz et al. reported 2 cases [

11]. In 2002, Maurer et al. published a paper chronicling 3 cases that occurred at their institution. A summary of key facts from each case is presented (

Table 1). The presentation for most of the cases was swelling in the submandibular area 6 weeks to 2.5 months after surgery. All patients had a sagittal split or a two-jaw surgery with a sagittal split. Furthermore, there is often a delay in establishing a diagnosis. In each paper, at least 1 case was treated with PO antibiotics alone with minimal to no resolution. In some cases, it took up to 2 months after presentation of swelling to identify the culprit as actinomycosis [

12]. Histological analysis was used to identify actinomycosis in 6 out of 7 of the reported cases. In all cases, the patient was treated with incision and drainage/excision of the mass as well as antibiotic therapy. The duration of antibiotic therapy varied from 6 weeks to 6 months. In 3 of the 7 cases, the plates were removed. This may indicate one author’s preference for treatment as all 3 cases were from the same institution [

12]. Another commonality is that the first sign of infection occurred at earliest 4 weeks from the time of surgery with 4 months from the time of surgery being the longest amount of time until the first signs of infection.

Discussion

Actinomycosis infection and been referred to as “the great pretender” due to its difficulty in diagnosis as well as its vague initial presentation [

13]. In comparing our case to the previously reported cases in the literature some conclusions can be drawn. It has been shown that most simple infections occur 2–3 weeks after the initial time or surgery and are usually easily managed with simple incision and drainage and a short course of antibiotics [

2,

4]. Conversely, all reported cases of actinomycosis infection occurred at 4 weeks or greater from the time of the initial surgery [

10,

11,

12]. This aligns with what is generally reported regarding cervicofacial actinomycosis in that there is a strong predilection for infection in the mandible when compared to the maxilla [

7]. Our patient was presented at 4 months after a sagittal split with a seemingly benign postoperative course. Late occurring infection should raise red flags following orthognathic surgery. That Prevotella oris was also identified in our patient is not surprising in that both organisms are found in the oral cavity.

In all the reported cases where an initial incision and drainage was performed and culture sent, actinomycosis was not identified in the cultures. However, in 2 of the 7 reported cases, a tissue sample was sent for histology at the time of initial incision and drainage [

12]. In these cases, they were able to establish actinomycosis more quickly as the causative agent and appropriately treat the patient. In our case, we did not send tissue samples with either of our incisions and drainage procedures. In hindsight, given the presentation and the type of fluid that was drained during the procedure in the operating room, a tissue sample should have been sent.

Our case is unique in that Actinomycosis Georgiae was cultured from the surgical wound rather than identified via gross histology from a tissue sample. We propose that in a mandibular infection presenting 4 weeks or greater after orthognathic surgery; it would be prudent to send a tissue sample for pathology as well as abscess culture. This may decrease the latency time of diagnosis in this rare disease entity.

Following the initial incision and drainage in the office the culture did not grow actinomycosis. When she presented with recurrent swelling the preferred antibiotic suggested by the initial culture did not treat her infection. In fact, in 4 days her symptoms were exacerbated, prompting an admission. This reinforces out how difficult it is to identify this organism.

Cases of cervicofacial actinomycosis are treated for a minimum of 6 weeks with a penicillin-based antibiotic, but often treatment regimens are recommended to be up to 6 months [

10]. The rational for longer treatment is that with these longstanding infections it is difficult to rule out some degree of osteomyelitis. While initially suspected, no evidence of osteomyelitis has manifested itself to date in our patient.

In addition, with titanium plates in place from the surgery, it may be necessary to empirically treat with 6 months of antibiotics due to the risk of bacterial biofilms. Coinfection with other organisms is not uncommon as in our case. Amoxicillin with Clavulanic acid is often recommended to cover both the actinomycosis and other causative microbes [

14].

Our patient’s immune system may have been comprised by her lack of glycemic control. Our patient had antibiotics prescribed for 6 months. No other cases of actinomycosis infection in orthognathic patient cite diabetes mellitus as a comorbidity in their patients.

Conclusions

While rare, cervicofacial actinomycosis is a possible complication following orthognathic surgery. A high index of suspicion for the disease should be raised in patient’s developing mandibular swelling or masses 4 weeks or more after surgery. In patients with this presentation, tissue histology as well as tissue culture should be sent at the time of presentation to assist in diagnosing and treating this disease.