Sliding Spine Relocation Surgery with Anterior Septal Reconstruction

Abstract

:Introduction

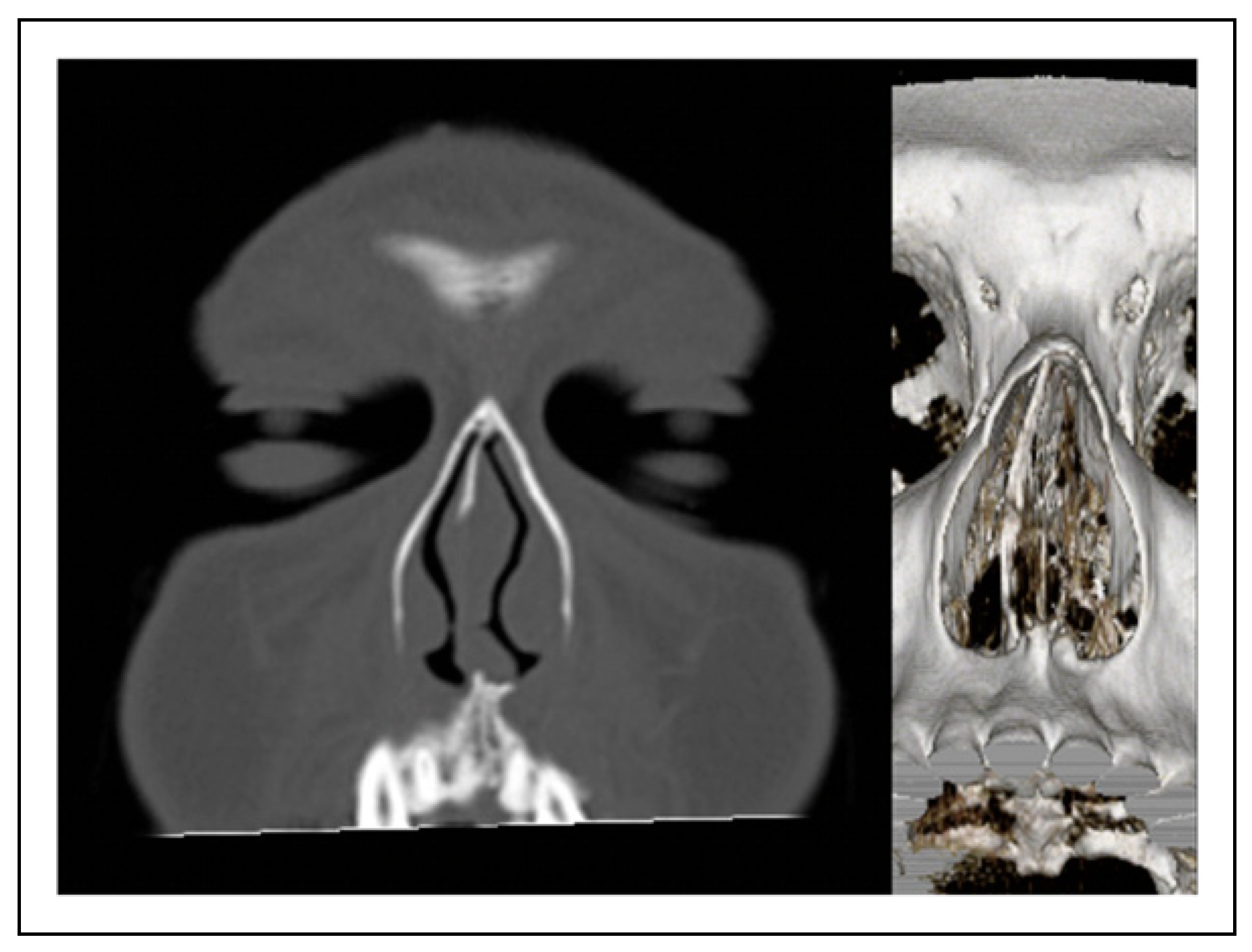

Case Report

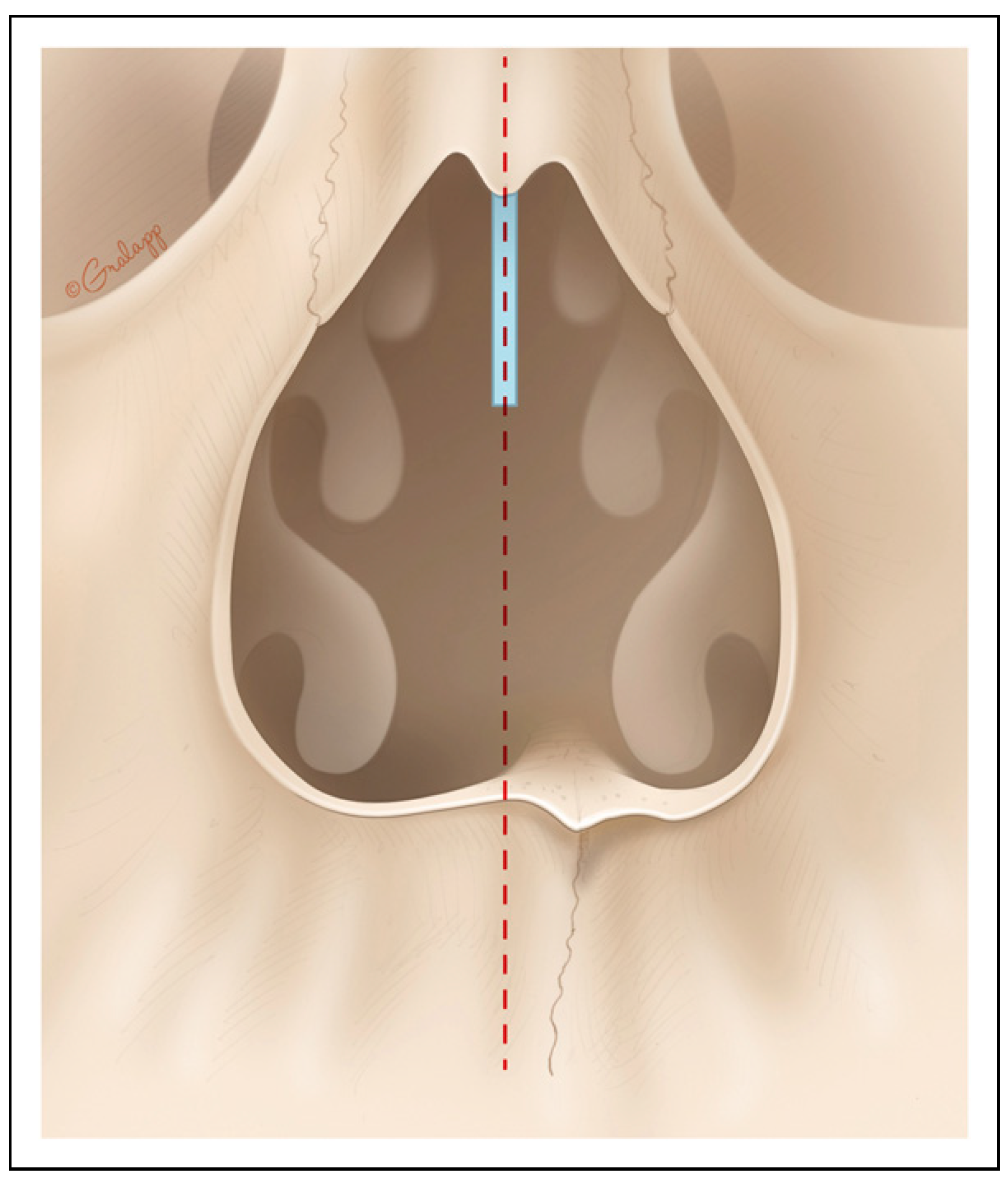

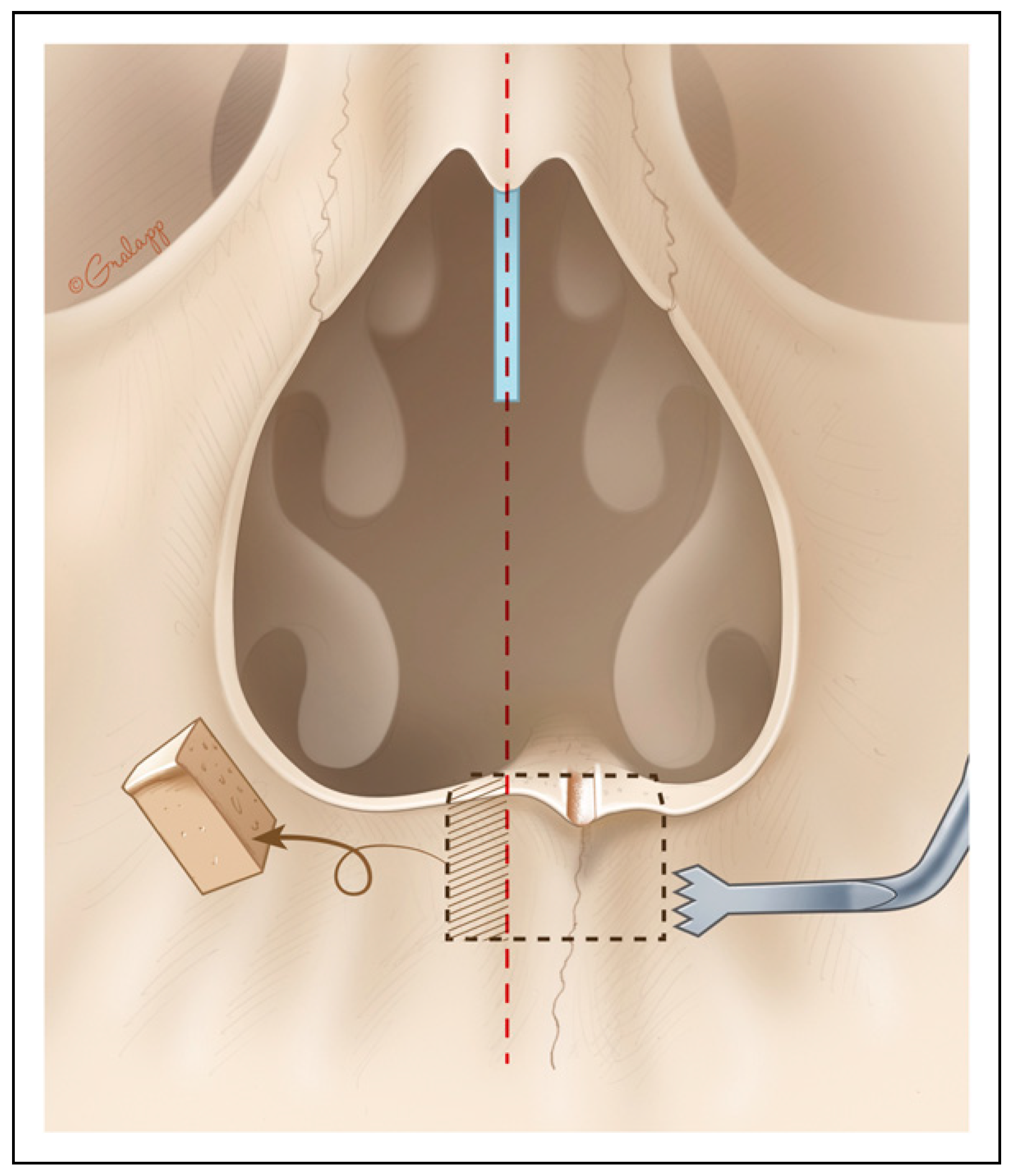

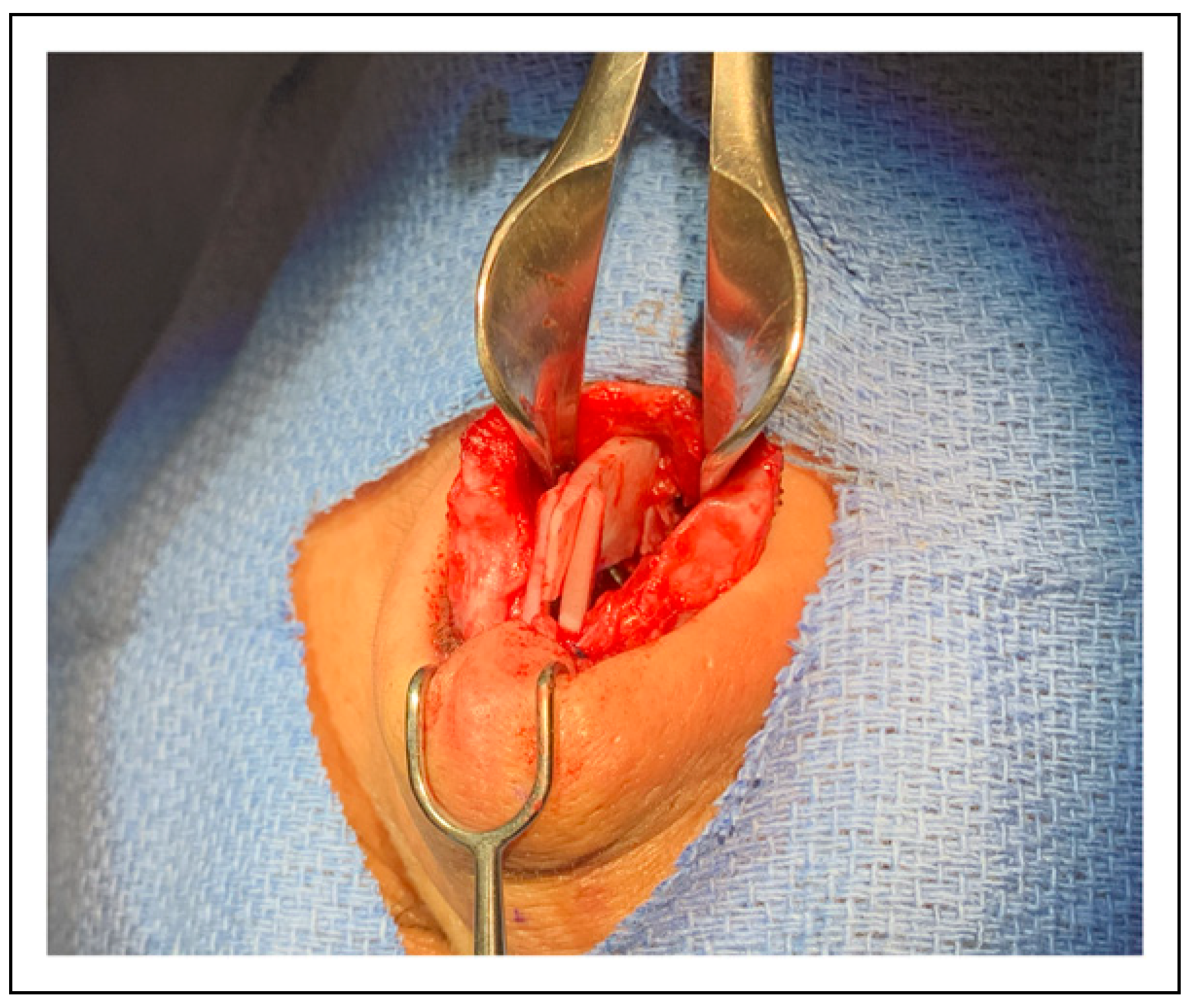

Surgical Technique

Discussion

Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rhee, J.S.; Weaver, E.M.; Park, S.S.; et al. Clinical consensus statement: Diagnosis and management of nasal valve com- promise. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010, 143, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spataro, E.; Most, S.P. Measuring nasal obstruction outcomes. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018, 51, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.; Friedman, O. Surgical treatment of nasal obstruction in rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2016, 43, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palesy, T.; Pratt, E.; Mrad, N.; Marcells, G.N.; Harvey, R.J. Airflow and patient-perceived improvement following rhinoplastic correction of external nasal valve dysfunction. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2015, 17, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.; Grunzweig, K.A.; Totonchi, A. Nasal obstruction and rhinoplasty: A focused literature review. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2020, 44, 1658–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Most, S.P. Trends in functional rhinoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2008, 10, 410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, Y.J.; Nam, S.H.; Choi, Y.W. Fracture of the anterior nasal spine. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012, 23, e160–e162. [Google Scholar]

- Marianetti, T.M.; Boccieri, A.; Pascali, M. Reshaping of the anterior nasal spine: An important step in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016, 4, e1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, M.; Liu, S.Y.; Certal, V.; Capasso, R.; Powell, N.B.; Riley, R.W. Large maxillomandibular advancements for obstructive sleep apnea: an operative technique evolved over 30 years. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015, 43, 1113–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, R.S.; Boyd, S.B. Facial soft tissue changes following maxillomandibular advancement for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007, 65, 1332–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.L.; Rival, R.; Solomon, P. Anterior nasal spine relocation for caudal septal deviation: A case series and discussion of common scenarios. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2020, 44, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guyuron, B.; Behmand, R.A. Caudal nasal deviation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003, 111, 2449–2457. [Google Scholar]

- Most, S.P. Anterior septal reconstruction: Outcomes after a modified extracorporeal septoplasty technique. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006, 8, 202–207. [Google Scholar]

- Surowitz, J.; Lee, M.K.; Most, S.P. Anterior septal reconstruction for treatment of severe caudal septal deviation: Clinical severity and outcomes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015, 153, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spataro, E.A.; Most, S.P. Tongue-in-groove technique for rhinoplasty: Technical refinements and considerations. Facial Plast Surg. 2018, 34, 529–538. [Google Scholar]

- Metzenbaum, M. Replacement of the lower end of the dis- located septal cartilage versus submucous resection of the dislocated end of the septal cartilage. Arch Otolaryngol. 1929, 9, 282–296. [Google Scholar]

- Peer, L.A. An operation to repair lateral displacement of the lower border of the septal cartilage. Arch Otolaryngol. 1937, 25, 475. [Google Scholar]

- Gubisch, W. The extracorporeal septum plasty: A technique to correct difficult nasal deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995, 95, 672–682. [Google Scholar]

- Gubisch, W. Extracorporeal septoplasty for the markedly deviated septum. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2005, 7, 218–226. [Google Scholar]

- Hafkamp, H.; Bruintjes, T.D.; Huizing, E. Functional anatomy of the premaxillary area. Rhinology. 1999, 37, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Constantine, F.C.; Ahmad, J.; Geissler, P.; Rohrich, R.J. Simplifying the management of caudal septal deviation in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014, 134, 379e–388e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gubisch, W. Invited discussion on: Anterior nasal Spine re- location for caudal septal deviation: A case series and discussion of common scenarios. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2020, 44, 508–510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.W.; Park, H.; Kwon, S.-M.; Koh, K.S. Anterior nasal spine relocation with cleft orthognathic surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2021, 32, 2812–2815. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2023 by the author. The Author(s) 2023.

Share and Cite

Fleury Curado, T.; El Abany, A.; Most, S.P. Sliding Spine Relocation Surgery with Anterior Septal Reconstruction. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2024, 17, 56-60. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875231152947

Fleury Curado T, El Abany A, Most SP. Sliding Spine Relocation Surgery with Anterior Septal Reconstruction. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2024; 17(1):56-60. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875231152947

Chicago/Turabian StyleFleury Curado, Thomaz, Ahmed El Abany, and Sam P. Most. 2024. "Sliding Spine Relocation Surgery with Anterior Septal Reconstruction" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 17, no. 1: 56-60. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875231152947

APA StyleFleury Curado, T., El Abany, A., & Most, S. P. (2024). Sliding Spine Relocation Surgery with Anterior Septal Reconstruction. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 17(1), 56-60. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875231152947