Abstract

Study Design: The following retrospective cohort study was competed using data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample a database from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Objective: The objective of this retrospective cohort study is to compare the hospitalization outcomes of managing maxillofacial trauma attempted suicide among handguns, shotguns, and hunting rifles. Methods: The primary predictor variable was the type of firearm. The outcome variables were the hospital charges (U.S. dollars) and length of stay (days). We used SPSS version 25 for Mac (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to conduct all statistical analyses. Results: A final sample of 223 patients was statistically analyzed. Relative to patients within the Q2 median household income quartile, patients in the Q4 median household income quartile added +$ 172'609 (P < .05) in hospital charges. Relative to patients living in "central" counties of metro areas, patients in micropolitan counties added +13.18 days (P < .05) to the length of stay. Relative to patients in the Q2 median household income quartile, patients in Q3 added +9.54 days (P < .05) while patients in Q4 added +11.49 days (P < .05) to the length of stay. Conclusions: Being within the highest income quartile was associated with increased hospital charges. Patients living in micropolitan counties have prolonged hospitalization relative to patients in metropolitan counties. Relative to the second income quartile, length of stay was higher in the third income quartile and highest in the fourth income quartile. Increase income grants access to deadlier firearms.

Introduction

Self-harm is a major public health problem that refers to intentional self-poisoning or self-injury, regardless of the motive, suicidal or not [1]. Self-harm can manifest in separate, distinguishable acts of destructive behavior grounded by different psychological motives. Self-harm is especially dangerous when the instrument of harm has the potential for lethal injury. Firearms are one such instrument of concern and almost always result in a fatality when employed for self-harm purposes. A study was conducted on Ontario residents who were injured from firearm discharges regardless of the circumstances surrounding the injury, whether it was assault or self-harm. Gomez et al revealed that firearms are much deadlier in self-harm than in the context of assault. The case fatality rate of injuries secondary to assault was 31.7%. On the other hand, the case fatality rate of injuries secondary to self-harm was a shocking 91.7%, nearly 3 times that of assault [2].

Although firearms are an effective means of suicide completion, unsuccessful attempts can significantly disfigure the craniomaxillofacial region. Craniomaxillofacial gunshot wounds often overwhelm the hospital care team at hand since the extent of trauma may be severe to the extent that initiating any treatment may seem pointless [3]. Indeed, ballistic injuries to the craniomaxillofacial region often indicate many surgical subspecialties in addition to maxillofacial surgery for a successful functional and esthetic prognosis [4].

The characteristics of gunshot wounds largely depend on the type of gun. Handguns fire projectiles of a relatively low velocity and caliber and produce penetrating injuries without an exit wound. On the other hand, rifles fire projectiles at relatively high velocity and, consequently, cause avulsive injuries (substantial tissue loss) with an exit wound. Shotguns fire numerous pellets at relatively low velocity. Because shotguns discharge powdered gases alongside the pellets, the resultant gunshot wounds are increasingly severe, with substantial tissue avulsion when the target contacts the muzzle [4]. Several studies investigated the management and reconstruction of maxillofacial gunshot wounds [3,5,6]. and the risk of mortality from self-inflicted gunshot wounds [7,8,9]. Nevertheless, no study to date has analyzed the hospitalization outcomes of self-inflicted gunshot wounds.

The purpose of the present study is to compare the hospitalization outcomes of managing maxillofacial trauma from attempted suicide among different types of firearms, particularly handguns, shotguns, and hunting rifles. Although not the primary purpose, we also wanted to explore the hospitalization outcomes for other demographic and hospitalization variables. We hypothesized that shotguns would correspond with significantly higher hospitalization charges and length of stay relative to handguns and rifles. We specifically aim to compare the (1) charges and (2) length of stay within the primary and secondary variables at hand. In so doing, we will determine which type of firearm, if any, is significantly associated with significantly increased hospital charges and length of stay. We will also determine other potential risk factors associated with increased hospital charges and length of stay. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to quantify the financial toll of managing self-inflicted gunshots.

Materials and Methods

The following retrospective cohort study was competed using data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), a database from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). The NIS is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient care database in the U.S., including data on more than 7 million hospitalizations each year. The NIS approximates a 20-percent stratified sample of all hospital discharges in the U.S., excluding rehabilitation and long-term acute care hospitals [10].

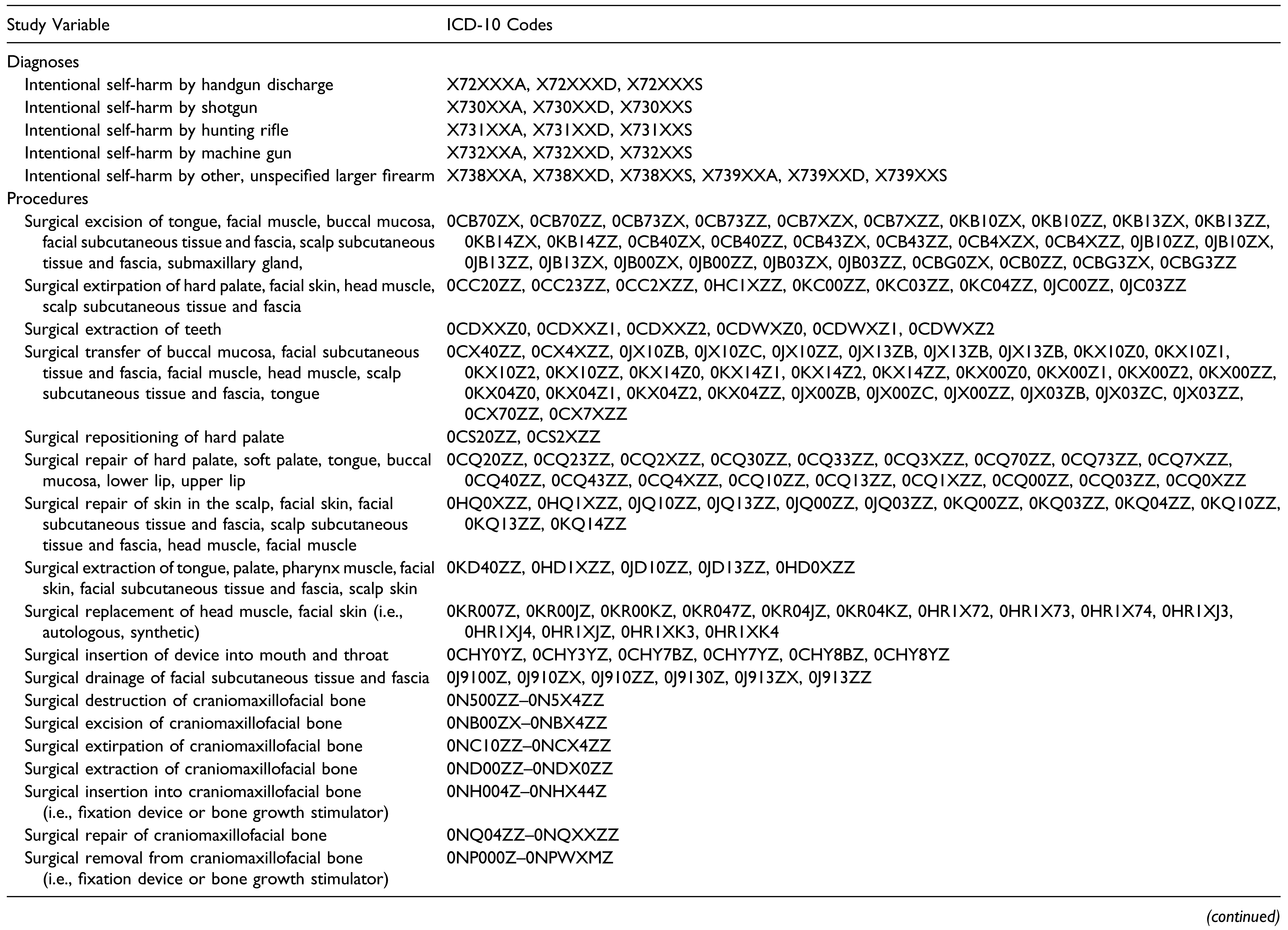

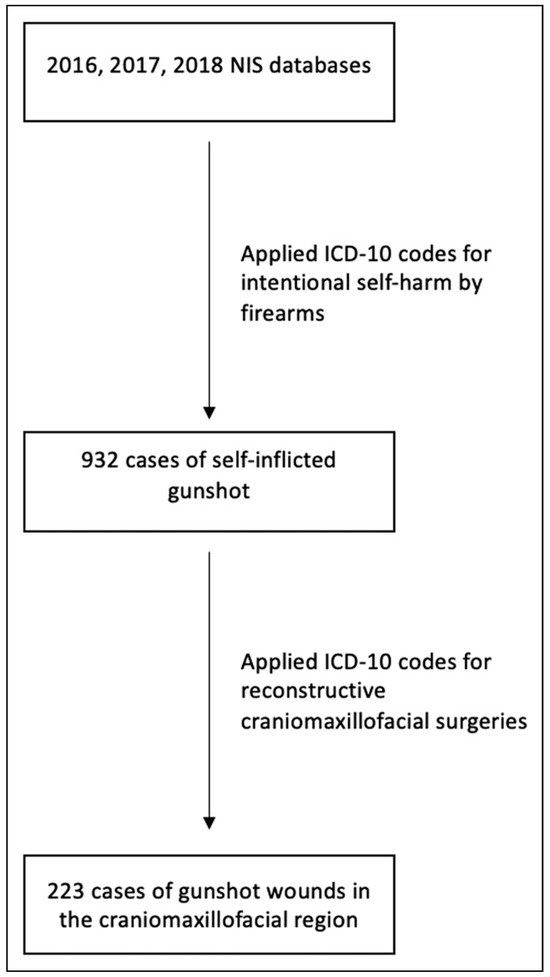

This lengthy screening process was completed by selecting all cases that entailed any form of craniomaxillofacial reconstructive surgery using the ICD-10 procedure codes. We used the ICD-10 diagnosis codes for intentional self-harm, specifically from handguns, shotguns, hunting rifles, and machine guns, to identify all patients who were hospitalized from firearm-assisted attempted suicide. Cases of intentional self-harm from air-guns and paintball guns were not included in the analysis. Amongst this filtered sample of patients, only injuries to the craniomaxillofacial region were selected for statistical analysis. Figure 1 illustrates a schematic diagram of the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Injuries to the neck were not included. Table 1 contains the ICD-10 codes that we utilized in the screening process.

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of subject selection from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS).

Table 1.

ICD-10 Codes Used to Identify Subjects and Define Variables.

Beginning with the year 2016, the NIS is a calendar year file that includes diagnoses and procedures coded using only International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification/Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-CM/PCS). Before October 1, 2015, the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis, procedure, and external cause of injury codes were used. To maintain the consistency of diagnostic and procedure codes, we used only data from the years 2016, 2017, and 2018. Because 2015 contained a mixture of ICD-9 and ICD-10, we did not include data from this calendar year file.

The primary predictor variable was the type of firearm (i.e., handguns, shotguns, hunting rifles, machine guns). The secondary predictor variables were patient age, sex, race, median household income, location, payer information, calendar year, form of admission (elective vs not elective), and hospital census region. The population from which the median household income was calculated consisted of all the residents within the confines of the patient’s zip code. Payer information indicated the primary payer of the hospitalization, which included either Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, self-pay, and other means. Private insurance entailed Blue Cross, commercial carriers, and private HMOs and PPOs. The ‘other’ category included worker’s Compensation, Title V, and other government programs. The hospital census region is defined by U.S. Census Bureau, grouping the states into either one of four main regions (i.e., Northeastern, Midwest, South, West). Patient location was stratified according to a six-category county classification scheme conceived by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The outcome variables were the hospital charges (U.S. dollars) and length of stay (days).

We used SPSS version 25 for Mac (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to conduct all statistical analyses. Because the NIS is a publicly available, anonymized database, the present study was exempt from institutional board review consistent with our medical center’s policy.

Results

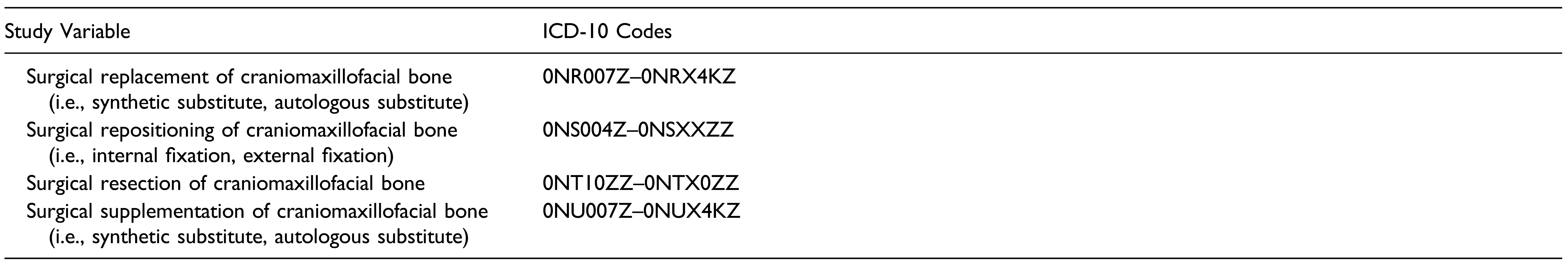

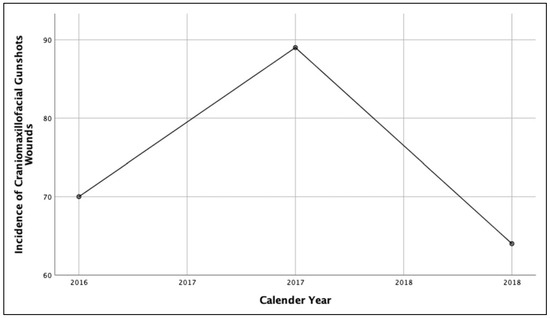

A sample of 932 patients was initially achieved after selecting for all cases that involved self-harm from firearms. After filtering for cases that entailed maxillofacial trauma, a final sample of 223 patients was statistically analyzed. The majority of patients were white (73.5%) men (85.2%) who were situated in the first (31.4%) and second (31.4%) income quartiles. The average age of the patients was 42.3 years. The most common primary payer was Medicare or Medicaid (47.5%). Not surprisingly, most patients were not admitted electively (92.8%). The mean length of stay (LOS) was 15.2 days post-admission. The average hospital charge was $ 234'958 per patient. The most frequent patient location was in a metro area county with a population ranging from 250,000 to 999,999. Insight into the type of firearm employed was available for 153 patients, from which the most frequently used firearm was the handgun (79.1%) while the least frequently used firearm was the hunting rifle (6.5%) (Table 2). Figure 2 illustrates the incidence of maxillofacial trauma secondary to attempted suicide across the calendar years included in this study. There was no significant trend with time.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients Who Suffered Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Secondary to Attempted Suicide Through the Use of Firearms.

Figure 2.

The incidence of maxillofacial trauma from attempted suicide with firearms across the 3 calendar years studied.

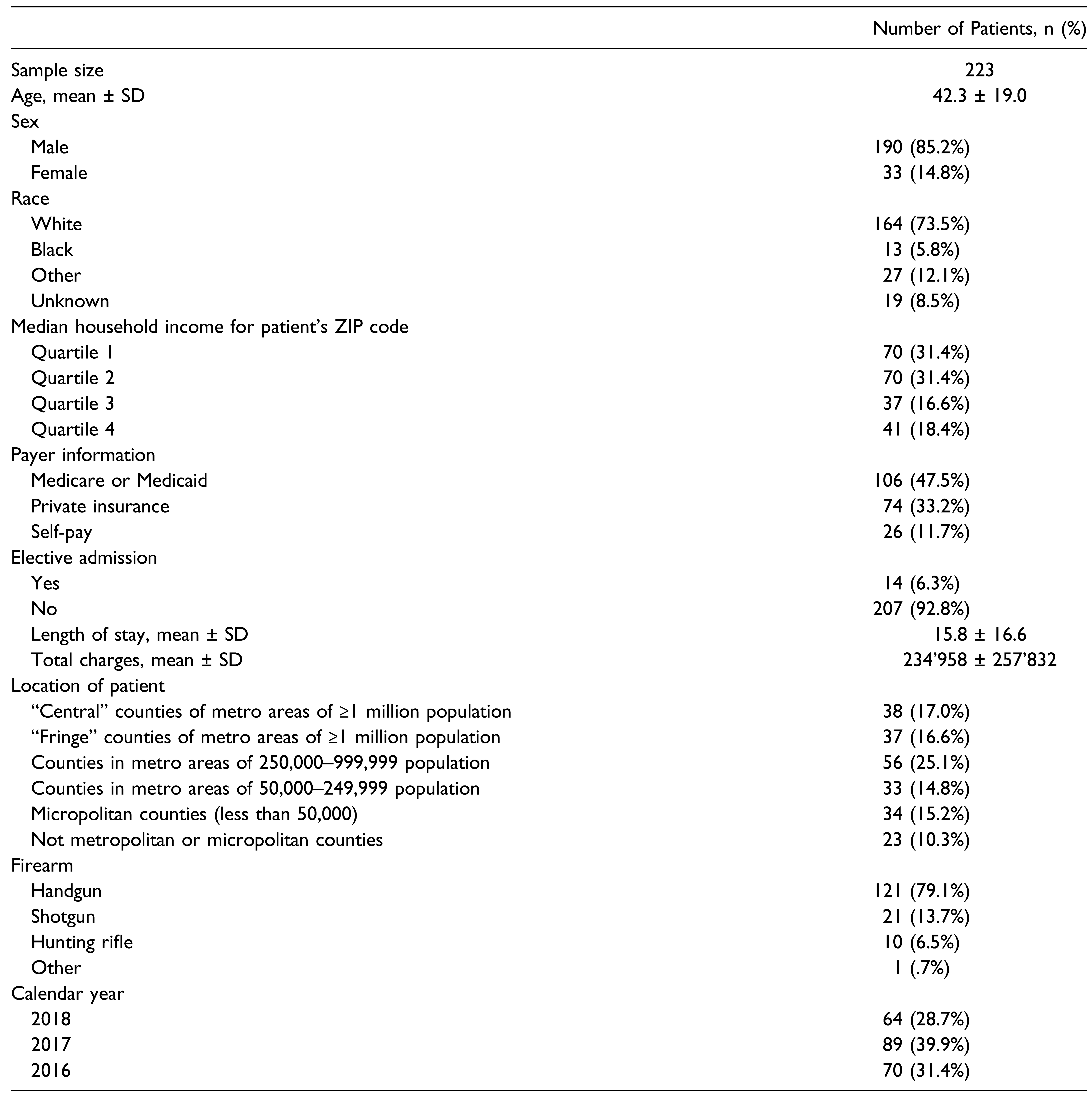

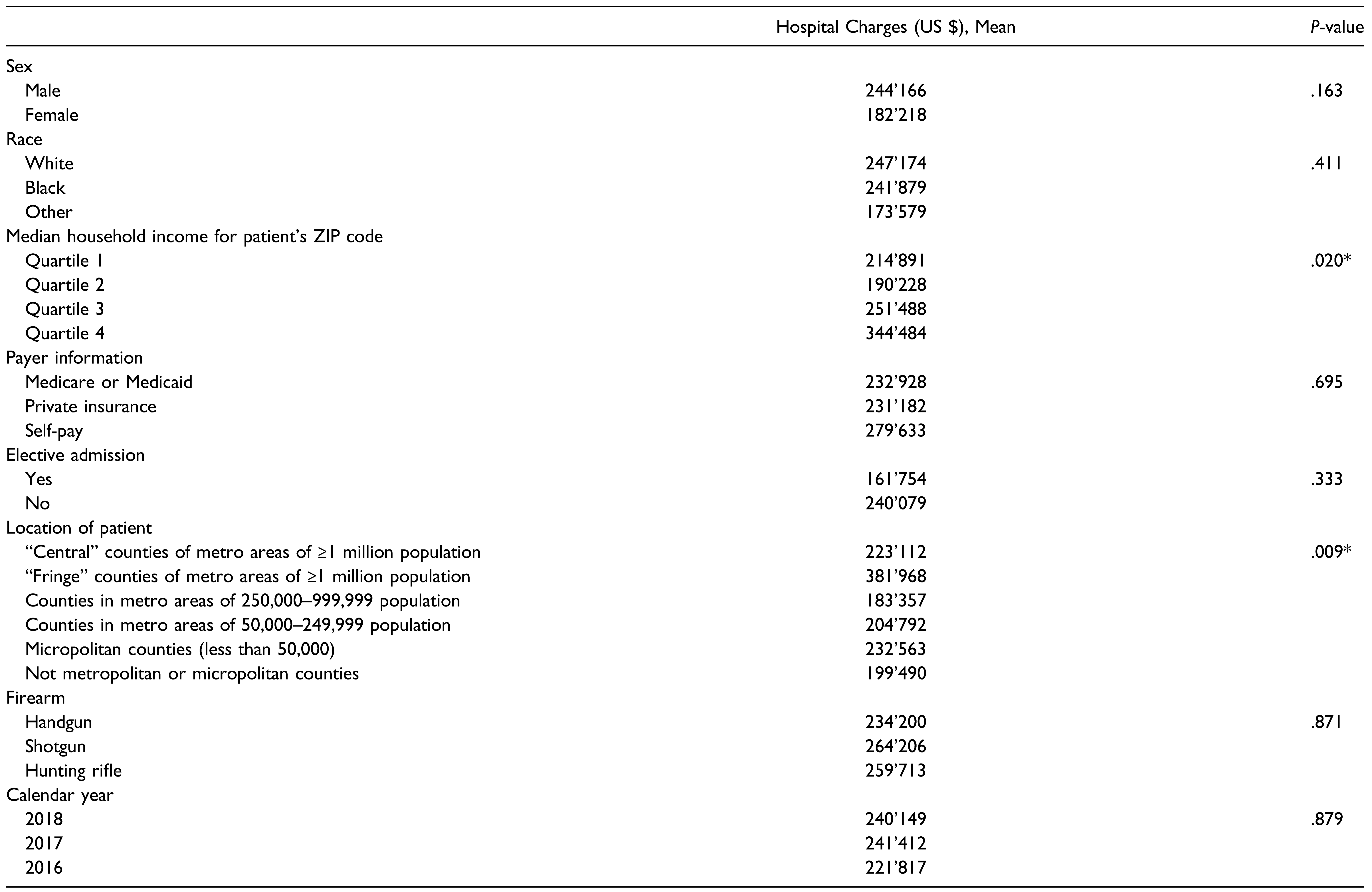

A bivariate comparison of the mean hospital charges for each variable was conducted (Table 3). Median household income and patient location were significant (P < .05) and were further analyzed via linear regression. However, biological variables, namely sex and race, and the key predictor variable, firearm, were included in the linear regression model despite not exhibiting significance in the univariate analysis. Variables with P < .2 were also included in the linear regression model.

Table 3.

Comparison of Hospital Charges for Each of the Predictor Variables.

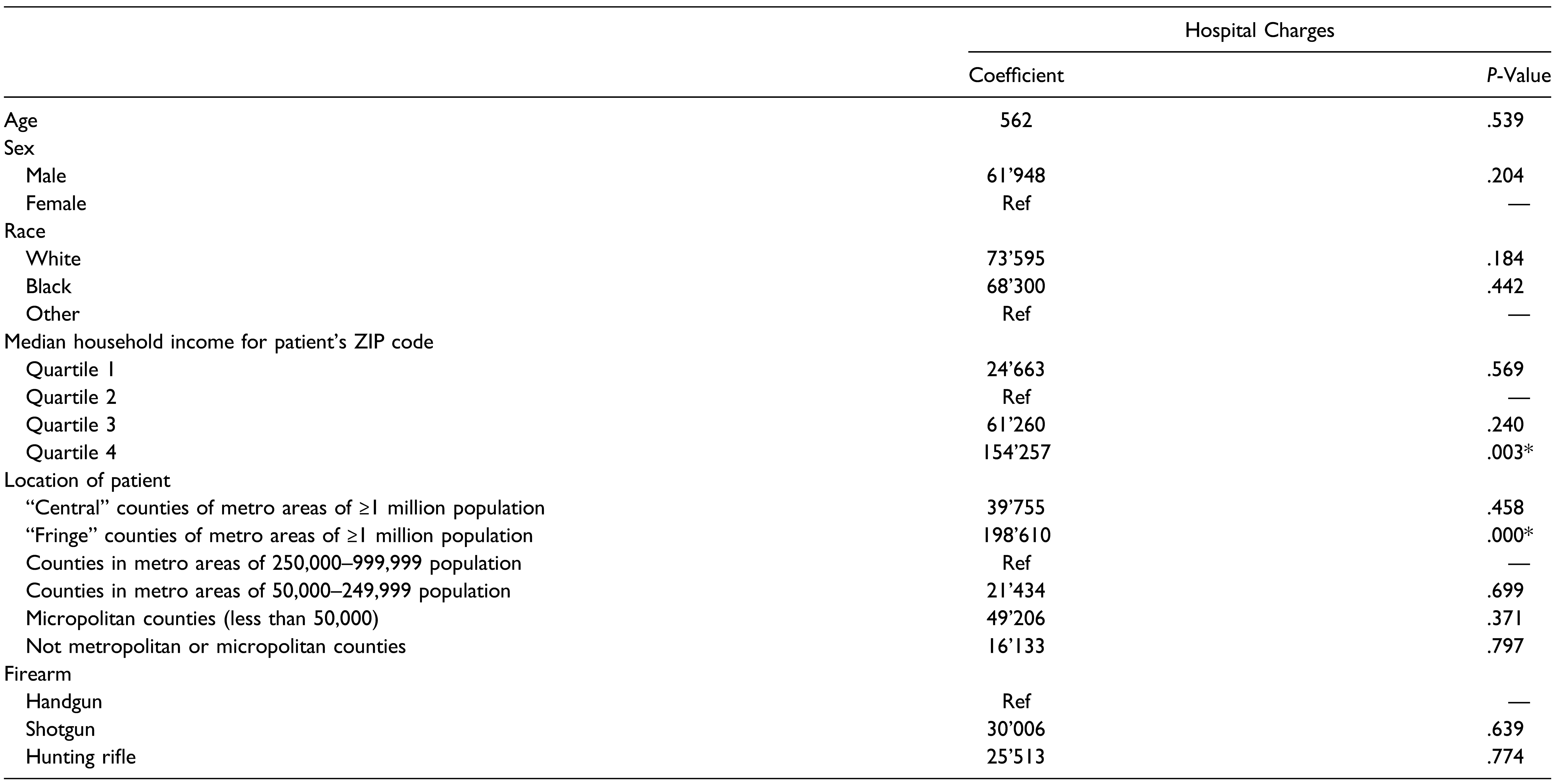

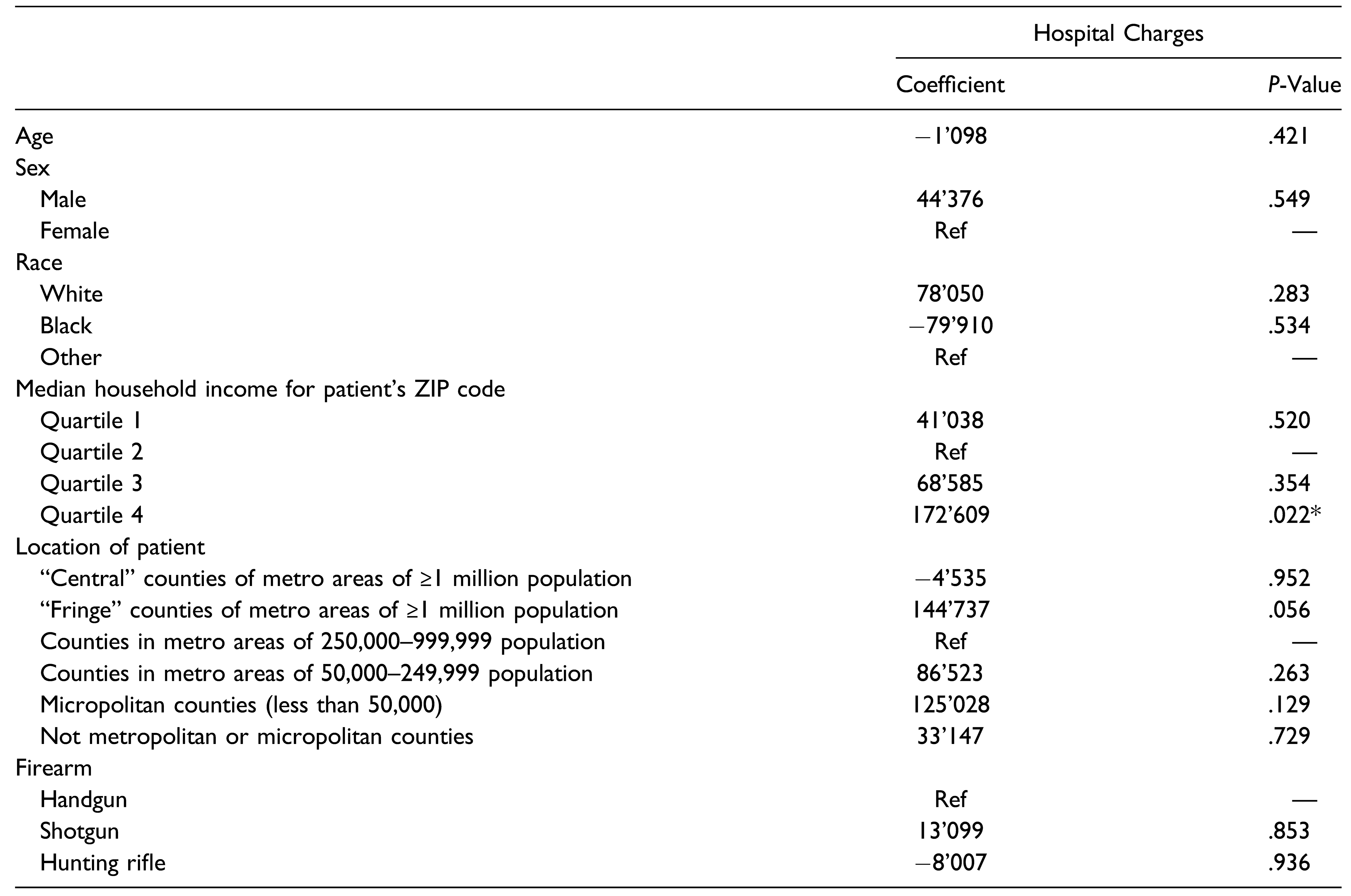

Univariate linear regression was conducted to determine if the mean hospital charge for each category was significantly higher than a designated reference category, which was typically that with the lowest hospital charge (Table 4). Increased hospital charge was associated with patients within the Q4 median household income quartile (P < .05) and patients living in “fringe” counties of metro areas of a population of a million or more (P < .05). After controlling for the covariates, the multiple linear regression model was conducted to determine if the predictor variables were independently associated with hospital charges (Table 5). Increased hospital charges remained to be significantly associated with patients within the Q4 median household income quartile (P < .05). Relative to patients within the Q2 median household income quartile, patients in the Q4 median household income quartile added +$ 172'609 (P < .05) in hospital charges.

Table 4.

Univariate Linear Regression Model for Hospital Charges.

Table 5.

Multiple Linear Regression Model for Hospital Charges.

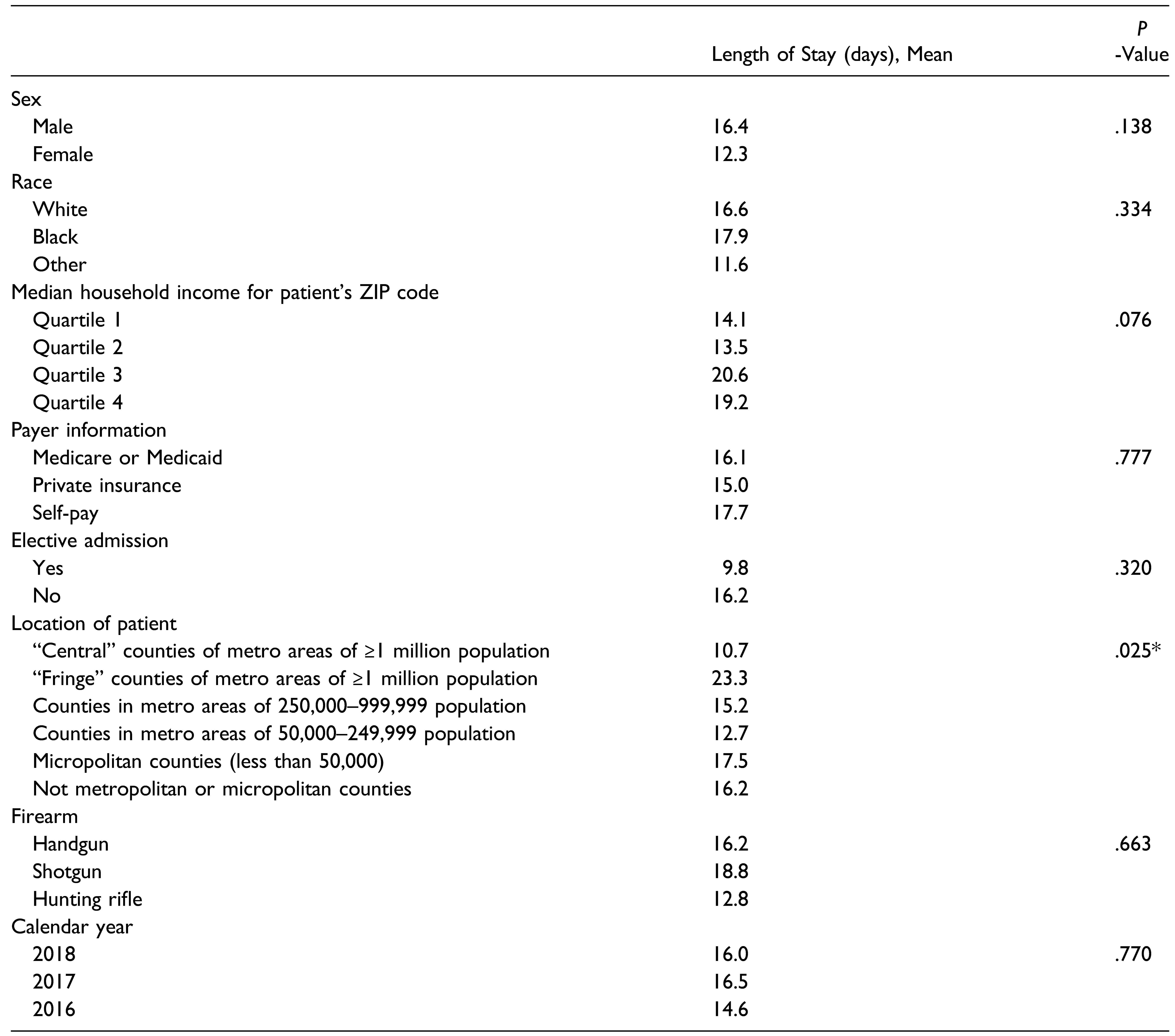

A bivariate comparison of the predictor variables with the length of stay was conducted (Table 6). The patient location (P < .05) proved to be a significant predictor and was further analyzed via linear regression. Similar to the previous bivariate comparison, biological variables, namely sex and race, and the key predictor variable, firearm, were included in the linear regression model despite not exhibiting significance in the univariate analysis. Variables with P < .2 were also included in the linear regression model.

Table 6.

Comparison of Length of Stay for Each of the Predictor Variables.

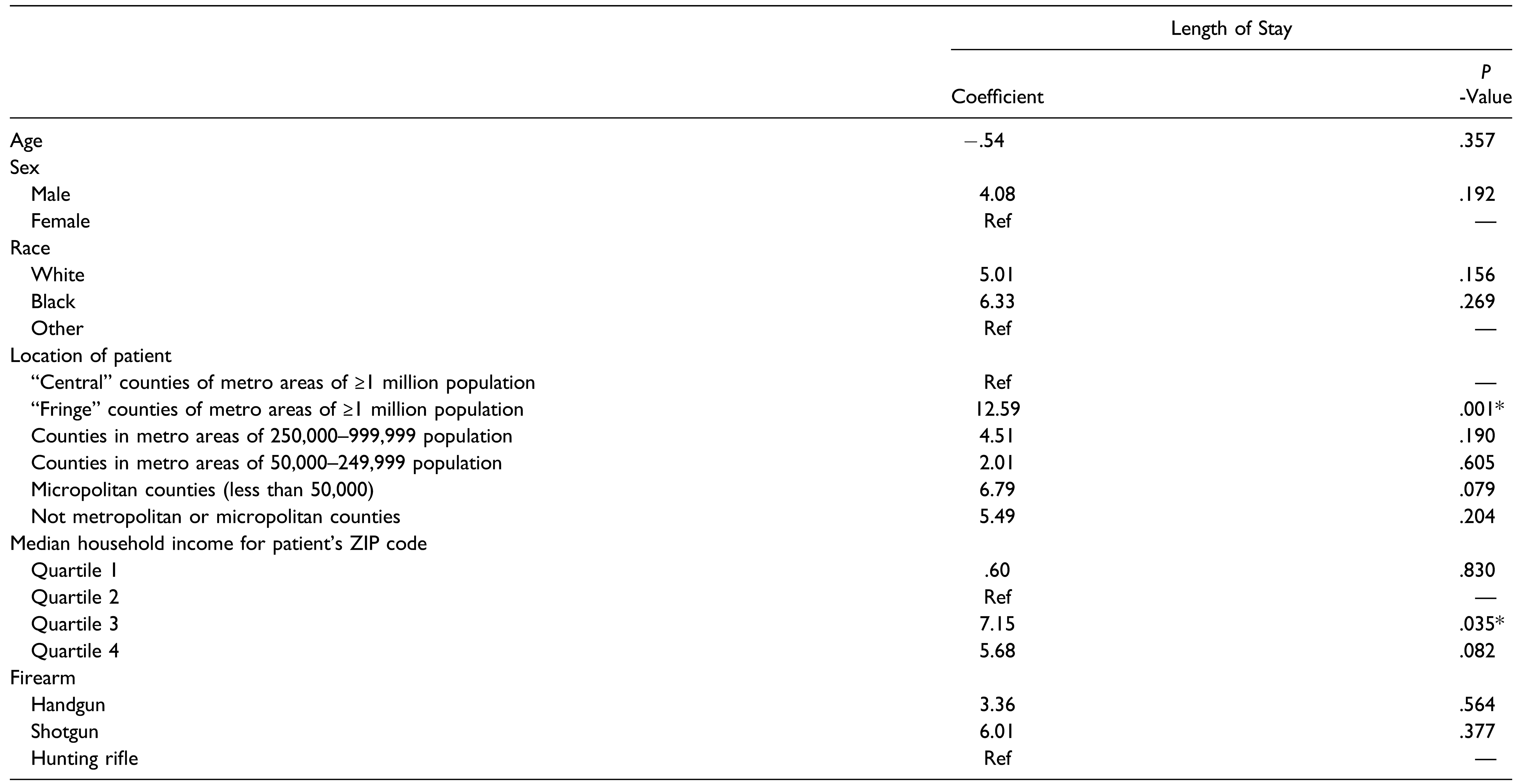

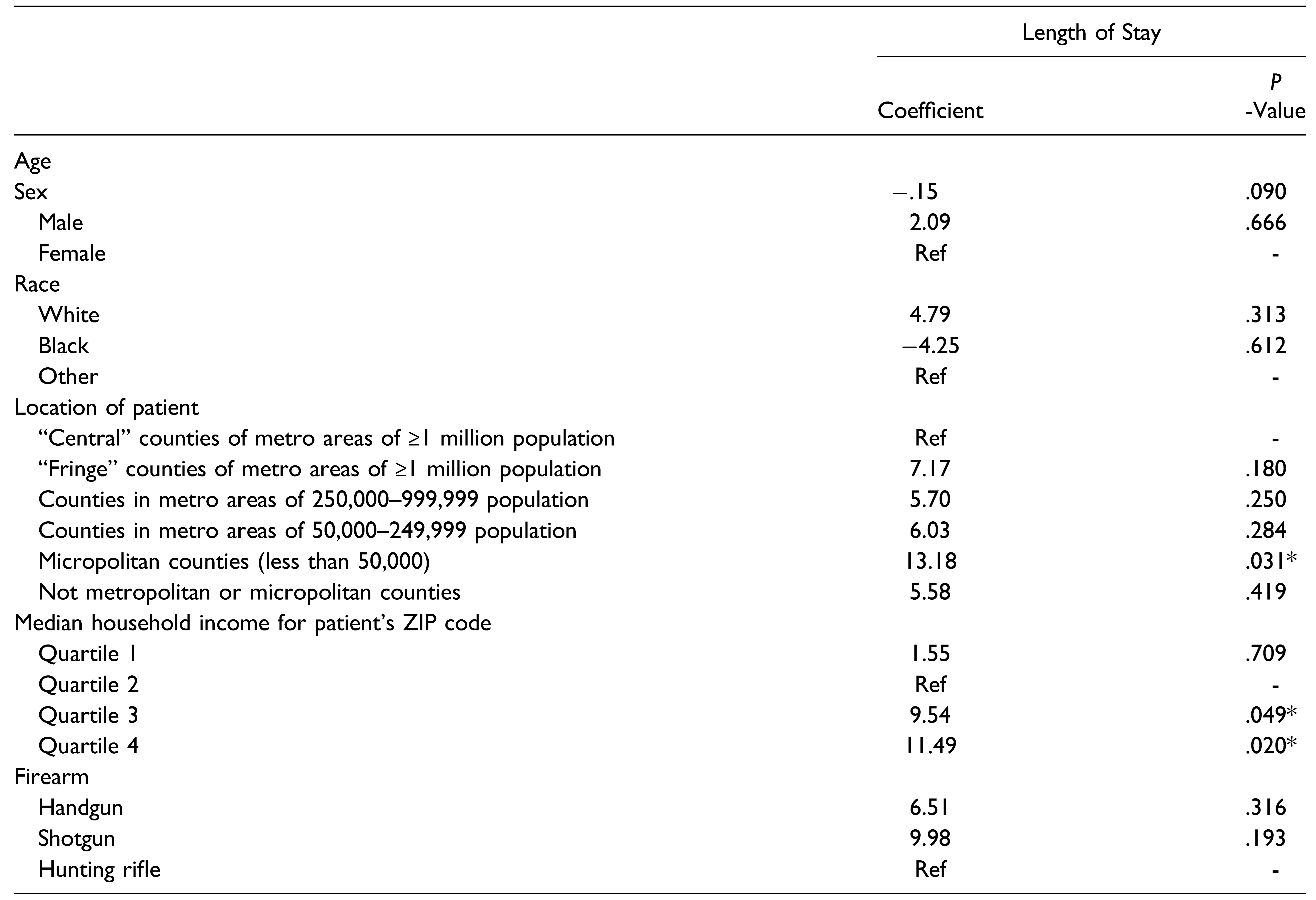

In the univariate linear regression model for length of stay (Table 7), patients living in “fringe” counties of metro areas of a population of a million or more (P < .05) and patients in the Q3 median household income quartile (P < .05) were independently associated with increased length of stay. After controlling for the covariates, the multiple linear regression model was conducted to determine if the predictor variables were independently associated with length of stay (Table 8). Relative to patients living in “central” counties of metro areas with a population greater than a million, patients in micropolitan counties added +13.18 days (P < .05) to the length of stay. Relative to patients in the Q2 median household income quartile, patients in Q3 added +9.54 days (P < .05) while patients in Q4 added +11.49 days (P < .05) to the length of stay.

Table 7.

Univariate Linear Regression Model for Length of Stay.

Table 8.

Multiple Linear Regression Model for Length of Stay.

Discussion

The purpose of this study is to gauge the hospitalization outcomes of self-inflicted gunshot wounds. We hypothesized that gunshot wounds from shotguns would be associated with increased hospital charges and length of stay. Our specific aims were to compare the hospitalization charges and length of stay within the primary variable (firearm type) and secondary variables at hand.

The typical patient in the study sample was a white male in his 40s who was in the lower (Q1 and Q2) income quartiles. The sex predilection of our study was highly consistent with several studies on self-inflicted gunshot wounds, as males comprise 87.1%,[7]. 85.5% [11], 86.6% [9], 87.0% [6], and 90.0% [12] of the respective study samples. The mean age in our study was also similar to that of other studies, which were 43.8 [7], 44.0 [11], and 44.9 [9] years, respectively. With regards to race, our study was consistent with two different studies [8,12]. An institutional study on self-inflicted gunshot wounds at the R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center of the University of Maryland Medical Center determined that 80% of patients were white [8,12]. It is important to discern this racial pattern when the gunshot wound is not self-inflicted and arose from other causes. A 10-year analysis of maxillofacial gunshot injuries from interpersonal violence determined that black patients comprised 47.2% of the sample, with white patients (36.3%) trailing behind. Hence, the issue of self-inflicted gunshot wounds plagues white men. Efforts need to be taken to safeguard this demographic from this permanently disfiguring injury.

Our study indicated that shotgun-induced gunshot wounds had the highest mean hospital charges. Relative to handguns, shotguns added more than $13,000 in mean hospital charges. This increase reflects the severity of shotgun GSWs relative to that of other firearms. While a shotgun’s capacity for damage is limited in range, the large mass of the pellets and gunpowder discharged at close range causes an exceptionally devastating wound. When it comes to rifles and handguns, the clinical difference in the weapon’s shooting range does not influence the severity of the wound regarding treatment [4]. Nevertheless, this difference in mean hospital charges for shotguns was not significant due to the sample size, and, hence, we did not reject the null hypothesis. The authors believe that it would otherwise have significantly increased mean hospital charges relative to handguns.

Being within the fourth income quartile ($71,000+annually), essentially the wealthiest population, added nearly 200,000 in hospital charges relative to the second income quartile ($43,000–59,000 annually). The authors believe that individuals in the highest income quartile tend to live in urban regions. Urban hospitals have higher mean hospital charges per discharge than rural hospitals in every state. This urban-rural charge difference varies with the state, being small in west Virginia and large in Nevada [13]. Another supposed rationale for this result is that the wealthiest population has access to deadlier firearms, which translates to more devastating gunshot wounds warranting prolonged hospitalizations.

Relative to patients living in “central” counties of metro areas with a population greater than a million, patients in micropolitan counties added +13.18 days (P < .05) to the length of stay. This trend is likely attributable to the differences between urban and rural hospitals. According to the 1997 annual survey of hospitals, rural hospitals (7.4 days) had a higher mean length of stay than urban hospitals (5.9) [13]. Urban hospitals likely possess a more diverse and experienced team of head and neck specialists who can manage many different gunshot wound presentations more effectively.

Relative to the second income quartile ($43,000–53,999 annually), the third quartile ($54,000–70,999 annually) added +9.54 days to the length of stay, while the fourth quartile ($71,000+ annually) added +11.49 days to the length of stay. After discussing this result, the authors believe the reason for this trend is that individuals in higher income quartiles have access to more dangerous firearms.

This study is not without limitations. First, the following study is a retrospective cohort study and, hence, we cannot determine definitive cause-and-effect relationships. Another limitation was the small sample size, which diluted many potentially significant results. The hospital charges from the NIS do not include outpatient care costs (i.e., lab work, revision surgeries, imaging). Therefore, this study likely underestimates the financial burden of self-inflicted gunshot wounds. Further, we had no insight into the intent of the self-inflicted gunshot wound. It is possible that some of these self-inflicted craniomaxillofacial gunshot wounds were purely accidental where the intent was not suicidal. With that said, this study stands out amongst the previous institutional studies on self-inflicted craniomaxillofacial gunshot wounds in that it is nationally representative instead of being confined to a particular institution within a city/state.

In conclusion, shotguns were associated with higher hospitalization charges and length of stay relative to the rest of the firearms. However, this difference was not significant due to the insufficient sample size. Regarding hospitalization charges, being within the highest income quartile was associated with increased hospital charges. This trend was likely due to the predominance of wealthy populations in urban regions, whose hospitals tend to have higher hospital charges than rural hospitals. Patients living in micropolitan counties have prolonged hospitalization relative to patients in metropolitan counties. Relative to the second income quartile, the length of stay was higher in the third income quartile and highest in the fourth income quartile. Increase income grants access to deadlier firearms.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Kendall, T.; Taylor, C.; Bhatti, H.; Chan, M.; Kapur, N. Guideline Development Group of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Longer term management of self harm: Summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2011, 343, d7073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, D.; Saunders, N.; Greene, B.; Santiago, R.; Ahmed, N.; Baxter, N.N. Firearm-related injuries and deaths in Ontario, Canada, 2002-2016: A population-based study. CMAJ 2020, 192, E1253–E1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuck, L.W.; Orgel, M.G.; Vogel, A.V. Self-inflicted gunshot wounds to the face: A review of 18 cases. J. Trauma. 1980, 20, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frost RJFHDBRVWMPPDE. Oral & Maxillofacial Trauma; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Firat, C.; Geyik, Y. Surgical modalities in gunshot wounds of the face. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2013, 24, 1322–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, O.; Mehra, P.; Salama, A. Maxillofacial gunshot injuries at an urban level I trauma center-10-year analysis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 73, 1532–1539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.; Markiewicz, M.R.; Bell, R.B.; Potter, B.E.; Dierks, E.J. Gun orientation in self-inflicted craniomaxillofacial gunshot wounds: Risk factors associated with fatality. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 41, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marschall, J.S.; Kushner, G.; Alpert, B. Are psychiatric history and substance use predictors of mortality in self-inflicted gunshot wounds to the face? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 78, e2041–e2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, J.A.; Lee, M.T.; Liu, X.; Warburton, G. Factors affecting survival following self-inflicted head and neck gunshot wounds: A single-centre retrospective review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 45, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quality AHIRa. Overview of the national (Nationwide) inpatient sample (NIS). 2021. Available online: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Murphy, J.A.; McWilliams, S.R.; Lee, M.; Warburton, G. Management of self-inflicted gunshot wounds to the face: Retrospective review from a single tertiary care trauma centre. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 56, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elegbede, A.; Wasicek, P.J.; Mermulla, S.; et al. Survival following self-inflicted gunshots to the Face. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 144, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hatten, J.M.; Connerton, R.E. Urban and rural hospitals: How do they differ? Health Care Financ. Rev. 1986, 8, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2022 by the authors. Multimed Inc.