Abstract

Study Design: In the year 2020, we saw the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 causing COVID-19 into a full blown pandemic. This resulted in constraints on healthcare resources, and the attention was shifted to reduce cross contamination and prevent spreader events. Maxillofacial trauma care was also affected similarly, and most of the cases were managed by closed reduction whenever possible. A retrospective study was conducted to document our experience in treating maxillofacial trauma cases before and after nationwide lockdown due to COVID-19 pandemic in India. Objective: The objective of the study was to compare the effect of pandemic in reported pattern of mandibular trauma and the result of closed reduction procedures in the management of single or multiple fractures in mandible during this time period. Methods: The study was conducted in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Maulana Azad institute of Dental Sciences, Delhi, for a period of 20 months, that is, 10 months before and after nationwide lock down which was effective from 23rd March 2020 due to COVID-19 pandemic. The cases were grouped into Group A (those reporting from 1st June 2019 to 31st March 2020) and Group B (those reporting from 1st April 2020 to 31st January 2021). Primary objectives were assessed and compared according to etiology, gender, location of the mandibular fractures, and treatment provided. Quality of life (QoL) associated with the treatment outcome by closed reduction was assessed after 2 months as a secondary objective using General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) in Group B. Results: A total of 798 patients sought treatment for mandibular fractures and included 476 patients in Group A and 322 in Group, B. The groups showed similar age and male: female ratio. Cases showed a steep fall during first wave of pandemic, and most of the cases occurred as result of RTA followed by fall and assault. The fractures due to fall and assault showed an obvious rise during the lockdown period. There were 718 (89.97%) patients having exclusive mandibular fractures and 80 (10.03%) patients having involvement of both mandible and maxilla. Single fractures of mandible constituted 110 (23.11%) and 58 (18.01%) in Group A and B, respectively. 324 patients (68.07%) and 226 patients (70.19%) had multiple fractures involving mandible in respective groups. Parasymphysis of mandible was most commonly involved (24.31%) followed closely by unilateral condyle (23.48%) then Angle and Ramus of mandible (20.71%) with coronoid being the least fractured. During the initial 6 months after lockdown, all the cases were treated successfully using closed reduction. GOHAI QoL assessment conducted in cases having exclusive mandibular fracture (210 Multiple, 48 Single) showed favorable results with significant (P < .05) difference between the single and multiple fractures. Conclusions: After one and half years and recovering from the second wave of pandemic that hit the country, we have come to understand COVID-19 better and embraced better management protocol. The study reveals that IMF remains the gold standard for the management of most of the facial fractures in pandemic situations. It was evident from the QoL data that most of the patients were able to carry out their day-to-day functions adequately. As the country prepares for a third wave of pandemic, management of maxillofacial trauma by closed reduction will remain the norm for most unless indicated otherwise.

Introduction

The year 2020 has been a defining moment in the routine workings of humankind as we saw the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causing COVID-19 into a full blown pandemic. On 11th of March 2020, WHO made the assessment that COVID-19 can be characterized as a pandemic [1]. As a result, governments around the world swept into action and adopted different models to prevent the outbreak from spreading inside their territories. Similarly, government of India also issued a total nationwide lockdown on 23rd of March 2020.

Trauma care all over the world took a hit as pandemic led to constraints on resources like health infrastructure and healthcare workers. In order to deal with the pandemic, all non-urgent hospital services like outpatient visits, nonessential footfalls in the emergency department, and elective interventions were postponed [2]. Maxillofacial surgery and surgeons performing it were also affected by it similarly. Authors around the world have found that though there was a drop in road traffic accidents (RTA), maxillofacial injuries due to other causes like fall and physical assault increased in number [3,4,5].

Maulana Azad Institute of Dental Sciences (MAIDS) being a tertiary care hospital associated with Lok Nayak Jai Prakash Narayan (LNJP) Hospital, a dedicated COVID care center in New Delhi, our recourses also were devoted to treat and manage the same. According to WHO advisory, only emergency oral healthcare interventions that were vital for preserving oral function, management of pain, and securing patients' quality of life were taken into consideration [5,6,7]. In view of pandemic, our institute adopted a COVID-19 protocol to reduce cross-contamination and spread by restricting aerosol-generating procedures. Thus, all the trauma cases reported were managed conservatively, that is, using closed reduction with Arch bar and Inter-maxillary fixation (IMF) whenever possible.

This paper is an endeavor to document our experience in treating maxillofacial trauma cases before and after nationwide lockdown due to COVID-19 pandemic and to study the treatment outcome in last year and reflect on the quality of life (QoL) of the patients who underwent closed reduction and fixation as treatment for their mandibular fractures. The primary objective of this study was to assess and compare the demographic and etiologic data along with recording the frequency of anatomical fracture distribution within the mandible. As a secondary outcome, we also assessed the QoL associated with the treatment using General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI).

Materials and Methods

The total number of patients who reported to our outpatient department with history of trauma were assessed retrospectively for a period of 20 months, that is, divided equally into 10 months before and after nationwide lockdown effective from 23rd March 2020 due to COVID-19 pandemic. We made an audit of all the patients having maxillofacial hard tissue injury excluding isolated midface, dental, and soft tissue injuries. The focus of the study was to compare the effect of pandemic in reported pattern of mandibular trauma and the result of closed reduction procedures in the management of single or multiple fractures in mandible during this time period.

For comparing the effect of pandemic in reported trauma, the cases were grouped into Group A and Group B starting from April 2020. Group A consisted of patients with mandibular hard tissue trauma from 1st June 2019 to 31st March 2020 and Group B consisted of same from 1st April 2020 to 31st January 2021. They were assessed according to etiology, gender, location of the fracture, and treatment provided. We also used this data to determine the frequency of anatomical distribution of fracture within the mandible. QoL associated with the treatment outcome was assessed as a secondary objective. All the patients who sought treatment during the pandemic (Group B) was treated adhering to institution’s COVID-19 protocol and after obtaining a negative COVID RT-PCR [8] result.

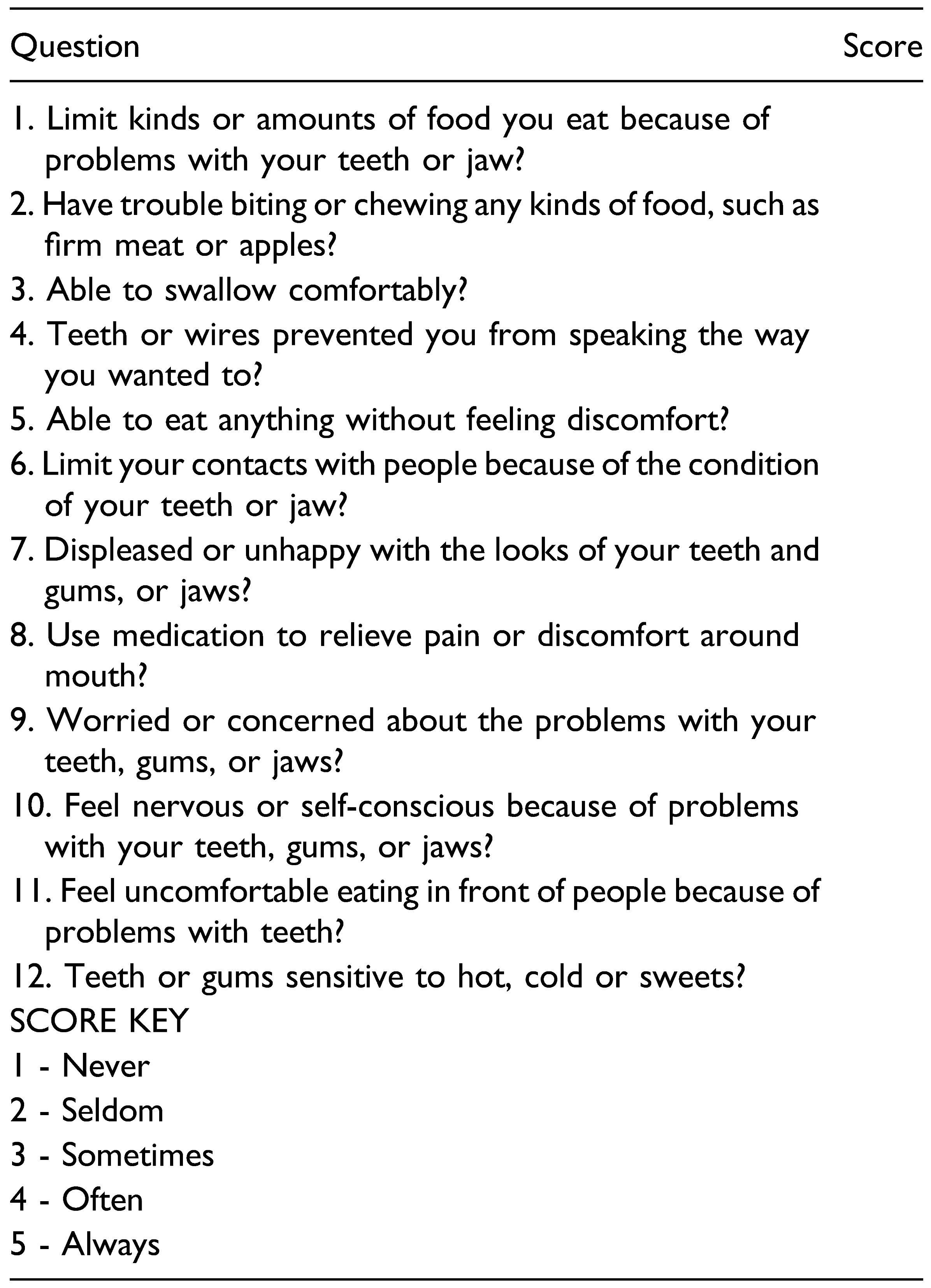

For evaluating the QoL associated with closed reduction and immobilization [using Erich Arch Bar and intermaxillary Fixation (IMF)] during the pandemic, General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI QoL), was done 2 months post procedure by asking the patients of Group B to answer self-report questionnaire either telephonically or by personal interview [9]. The GOHAI QoL questionnaire consists of 12 questions, reflecting 1 for the least score (never) and 5 for the maximum score (always) for each individual item except for question 3 and 5 which were asked in a positive sense and hence scores are reversed (Table 1). It comprises of 2 factors: a “physical worry” factor, comprising of items on one’s oral health, use of pain medication, problems with eating, and esthetics; and a “social” factor, comprising items regarding limitation of social contacts, problems with speaking, and discomfort in eating with others. Patient who underwent open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), patients not willing to answer the GOHAI questionnaire, and Patients unavailable for the Figure 2. study were excluded. As response by patients having single and multiple fracture could show obvious bias, assessment was done separately. Absolute numbers and simple percentages were used to describe categorical variables. Using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) software, paired t-test was done to statistically analyze the significance of result in case of single and multiple fractures, gender, and age group. Relationship of etiology was statistically analyzed using one way ANOVA. A P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 1.

GOHAI questionnaire and key scores of question 3 and 5 is reversed for assessment.

Figure 2.

a. Comparison of Total Cases - According to Etiology. b. Number of Cases per month in Group A - According to Etiology. c. Number of Cases per month in Group B - According to Etiology.

Results

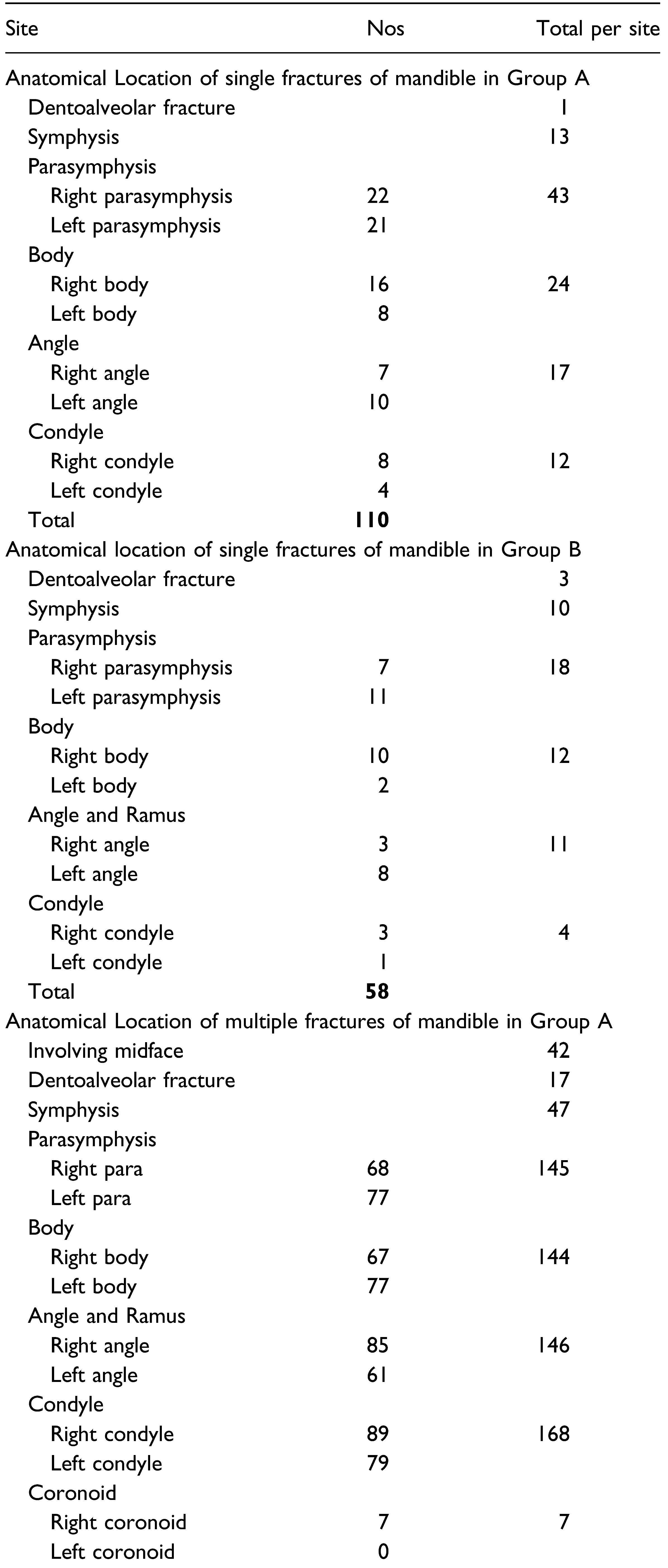

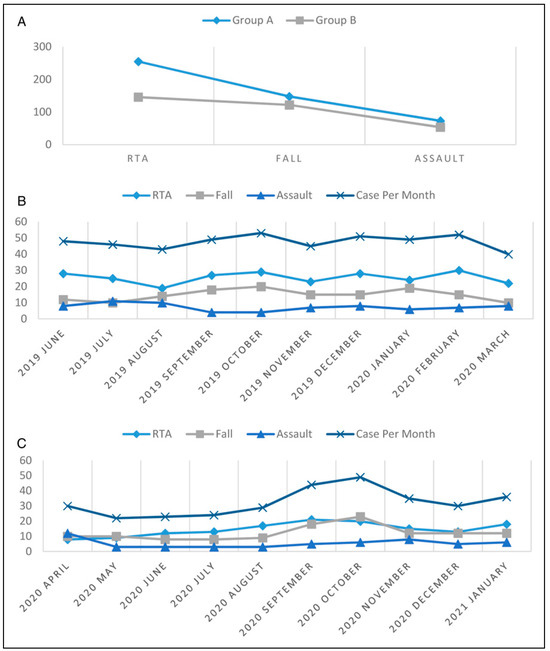

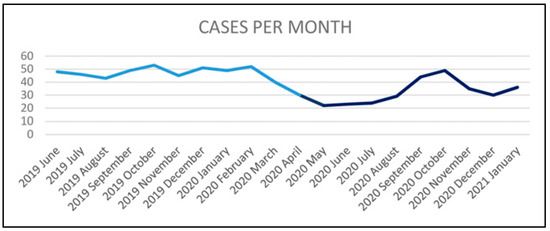

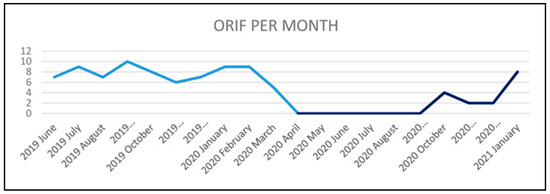

A total of 798 patients sought treatment in our outpatient department for maxillofacial hard tissue injury to mandible during the 20 month time period. This included 476 patients in Group A (1st June 2019 to 31st March 2020) and 322 in Group B (1st April 2020 to 31st January 2021). Both groups had similar mean age, that is, 27.67 ± 8.08 years and 26.25 ± 7.45 years, respectively. The data shows that there was obvious decrease in trauma related footfall after and during lock down due to pandemic (Figure 1). These cases showed a steep fall during first wave of pandemic, that is, initial months after lockdown and showed a gradual return to pre-pandemic times as of January 2021.

Figure 1.

Line diagram corresponding to month wise incidence of trauma in Group A (Light blue) & Group B (Dark blue).

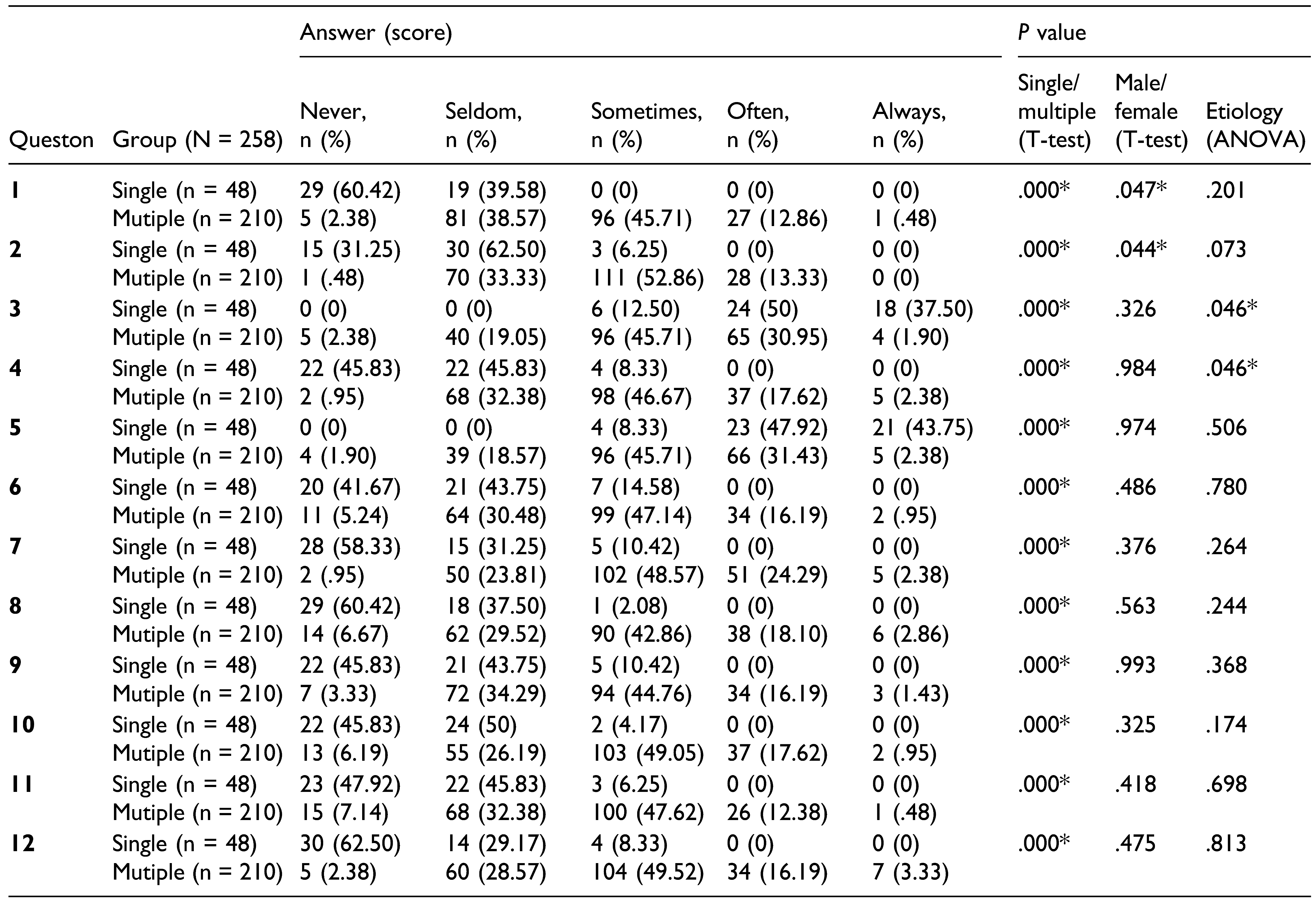

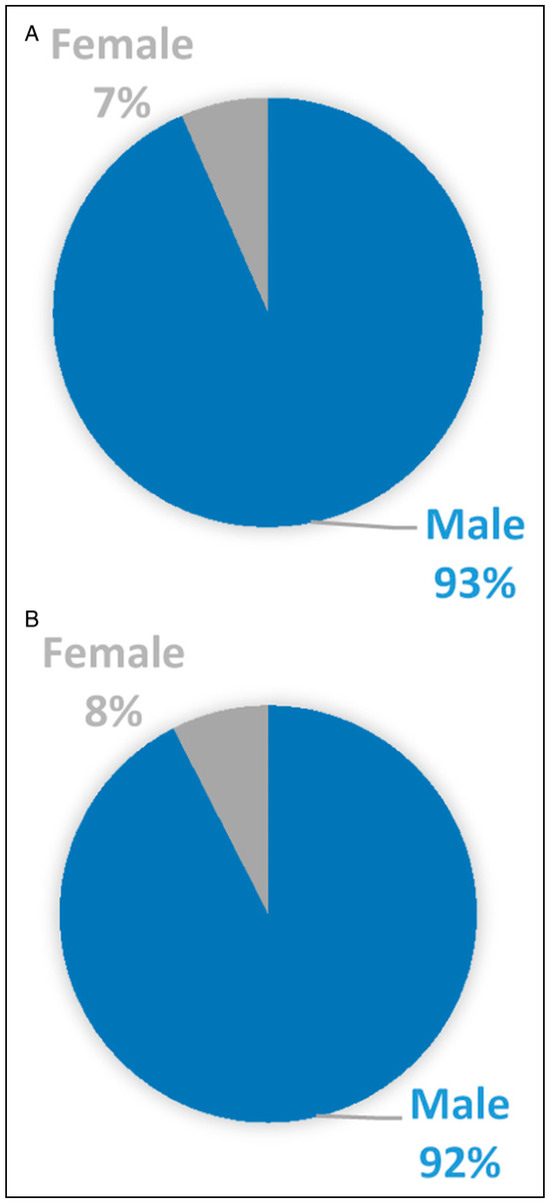

Regarding etiology, most of the cases occurred as result of RTA followed by fall and assault. The ratio of fall and assault related fractures showed an obvious rise during the lockdown period, that is, 221 out of 476 (46.42%) in Group A and 176 out of 322 (54.65%) in Group B (Figure 2a-c). When it came to gender, there were 445 males and 31 females in Group A, while there were 297 males and 25 females in Group B. The male: female ratio remained similar in both groups (Figure 3a and b).

Figure 3.

a. Comparison of number of Cases According to Gender in Group A. b. Comparison of number of Cases According to Gender in Group B.

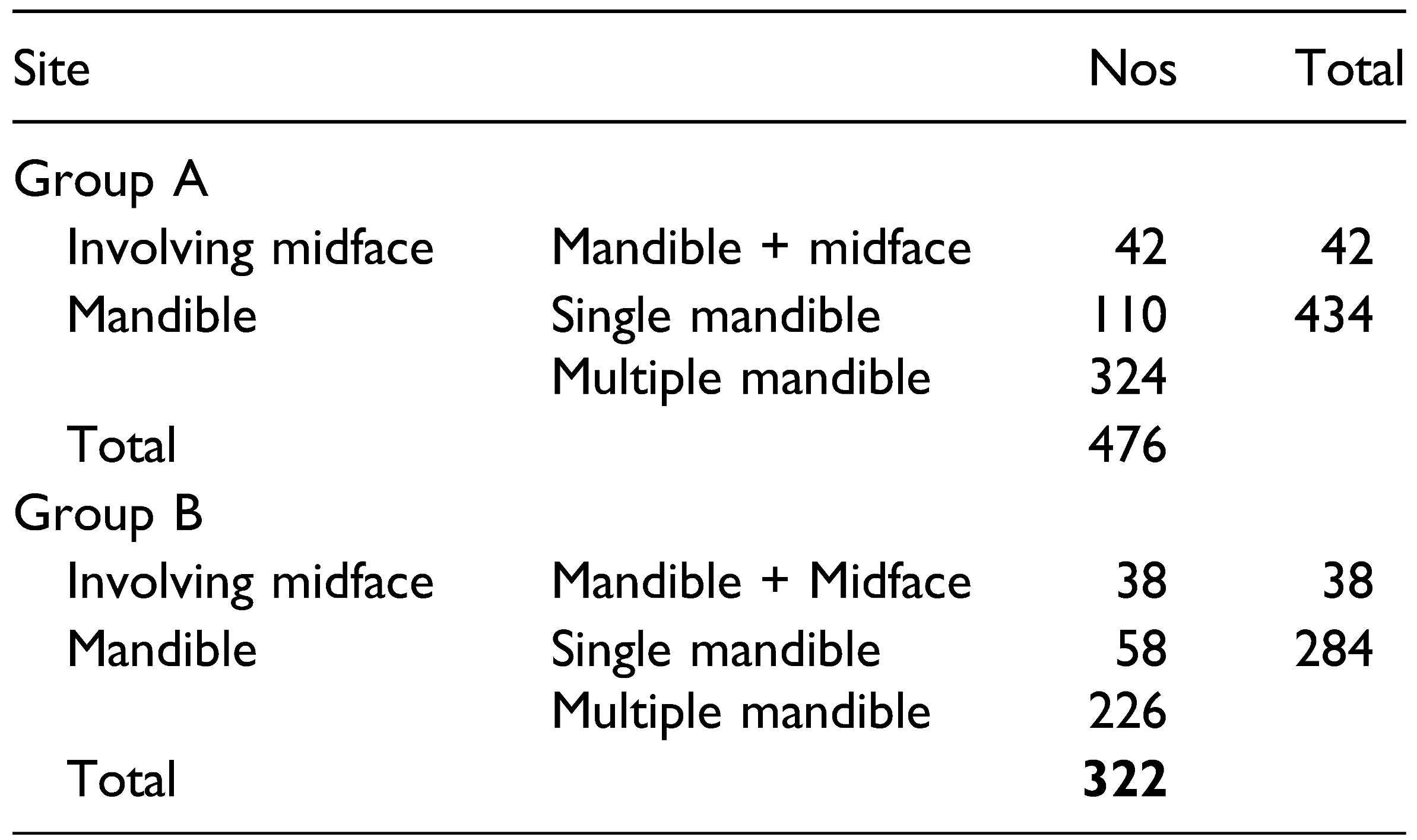

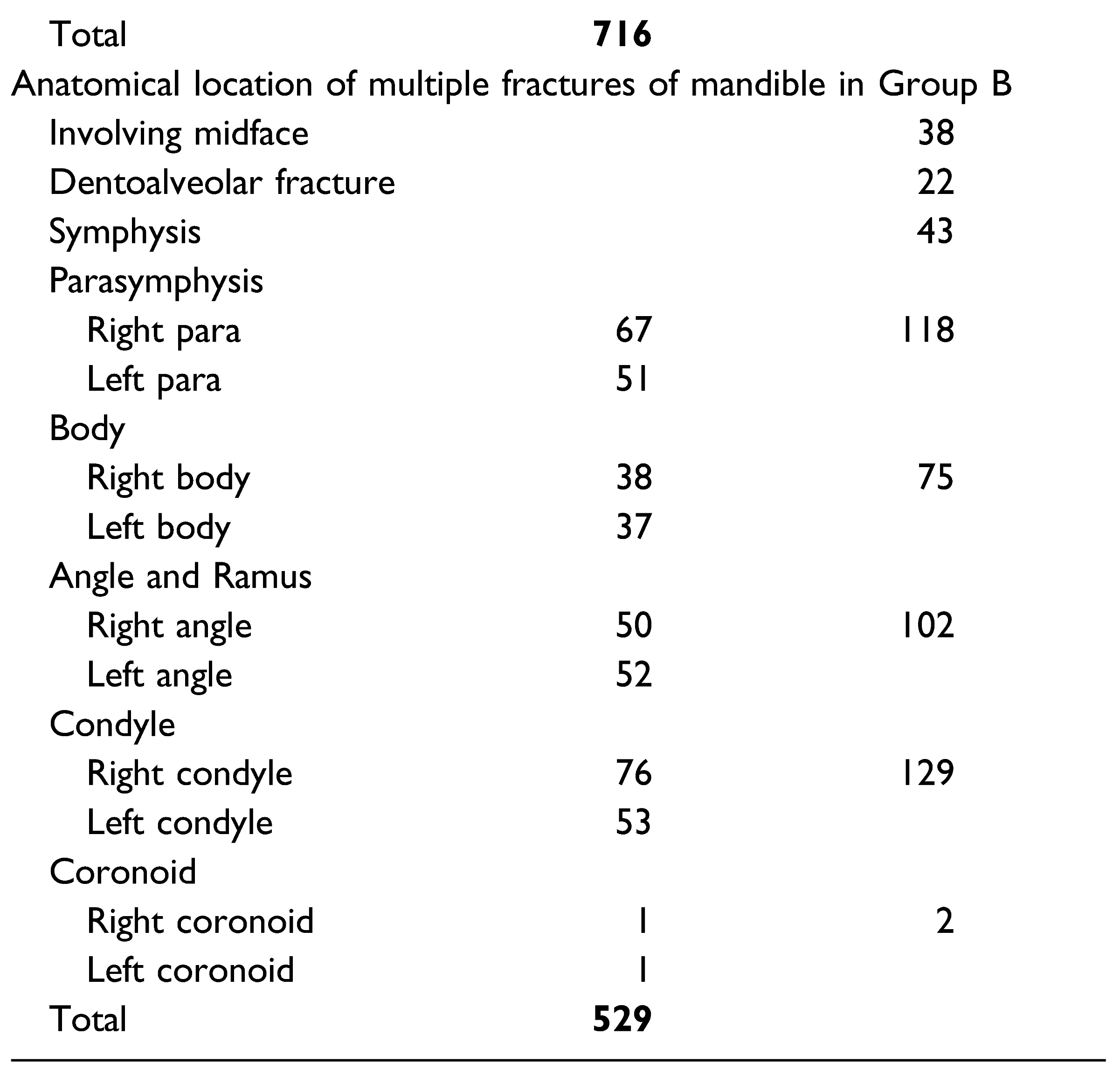

The data obtained from 798 patients showed there was 718 (89.97%) patients having exclusive mandibular fractures and 80 (10.03%) patients having involvement of both mandible and midface. The mandibular fractures were described according to classification by Dingman and Natvig [10]. The anatomical location of fractures within the mandible showed usual patterns. While the single fractures of mandible of both time period was dominated by fractures of parasymphysis, multiple fractures showed more of condylar involvement. The patients were grouped according to number of fracture sites, that is, single and multiple for ease of documentations and to compare severity. It also aided in reducing bias while assessing GOHAI QoL. Single fractures of mandible constituted to 110 (23.11%) and 58 (18.01%) in Group A and B, respectively. 324 patients (68.07%) and 226 patients (70.19%) had multiple fractures involving mandible in respective groups. (Table 2). The comparison of fractures according to anatomical location within mandible of Group A and B are given in Table 3.

Table 2.

a. Number of cases according to location of fractures in Group A. b. Number of cases according to location of fractures in Group B.

Table 3.

a. Anatomical Location of single fractures of mandible in Group A. b. Anatomical Location of single fractures of mandible in Group B. c. Anatomical Location of multiple fractures of mandible in Group A. d. Anatomical Location of multiple fractures of mandible in Group B.

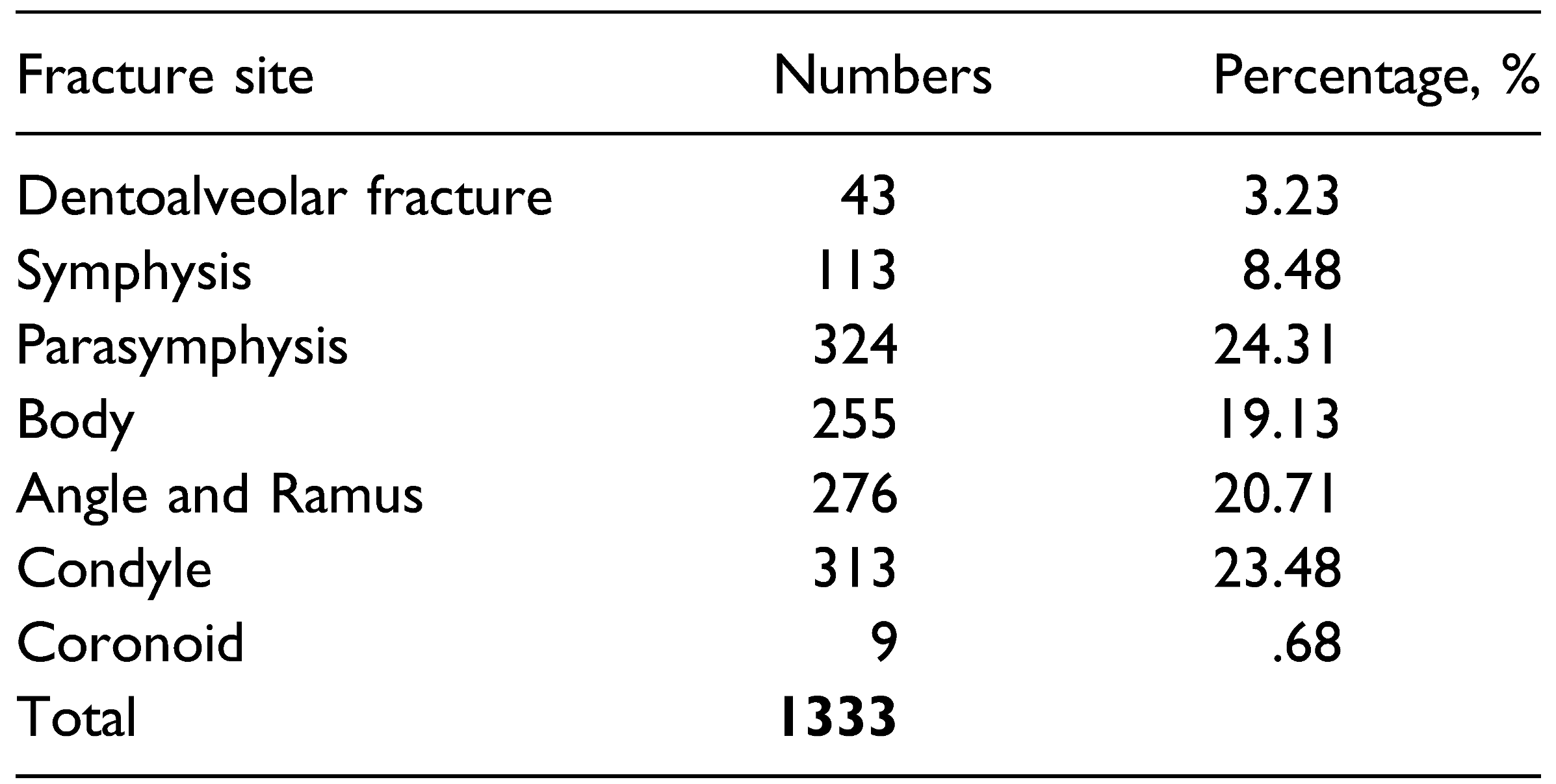

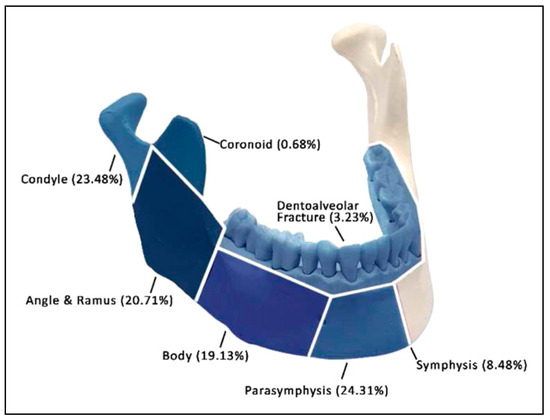

The data on pattern of fracture found that there were 1333 fracture sites within mandible among the 798 patients. With this data available, we took the opportunity to revisit the frequency of anatomical location of fractures within the mandible and found that parasymphysis of mandible was most to be involved (24.31%) followed closely by condyle (23.48%) then Angle and Ramus of mandible (20.71%) with coronoid being the least fractured (Table 4 and Figure 4).

Table 4.

Frequency of anatomical location of fractures within mandible of 798 patients during study period.

Figure 4.

Frequency of anatomical location of fracture within mandible of 798 patients (1333 fracture sites) during study period.

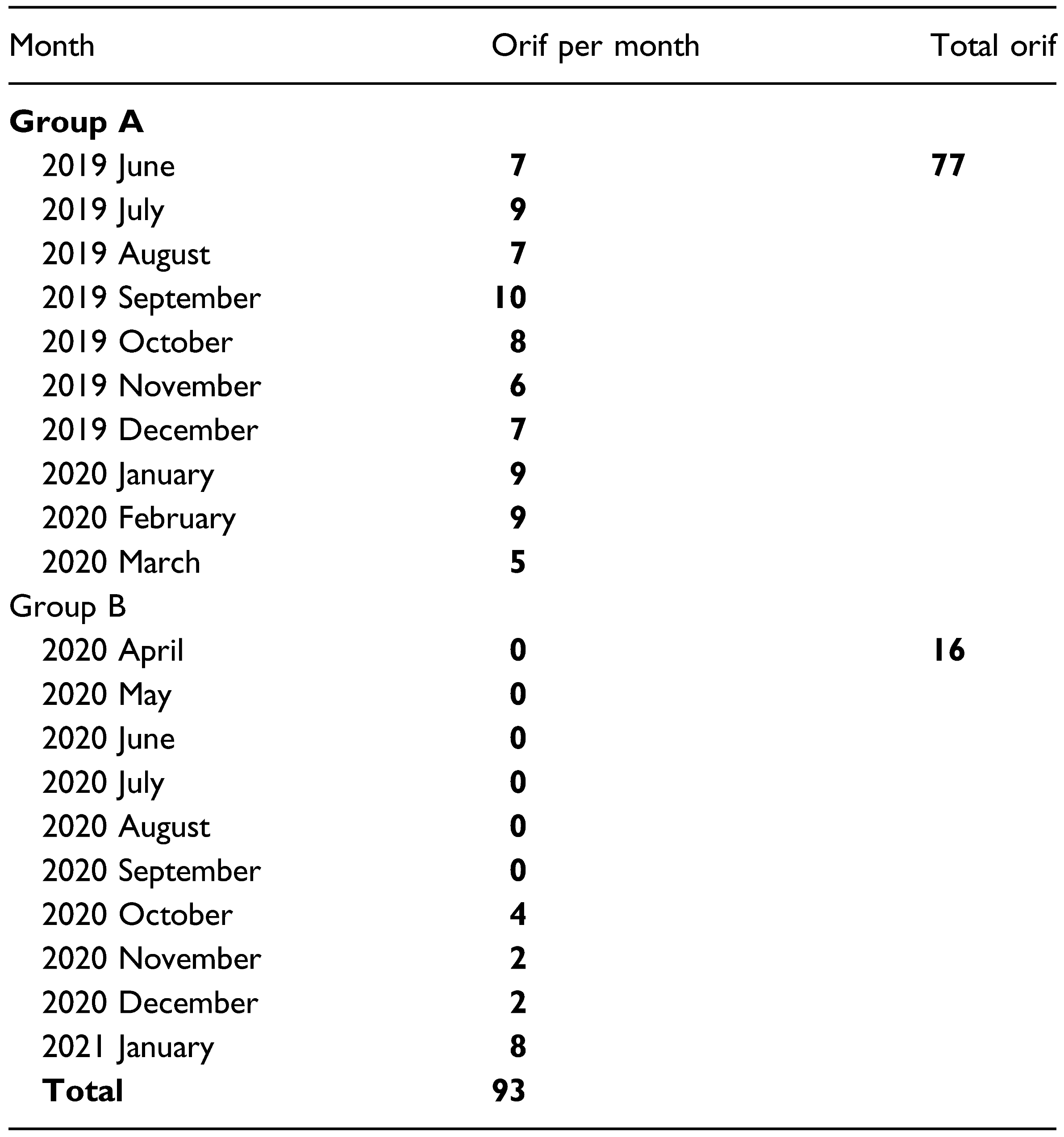

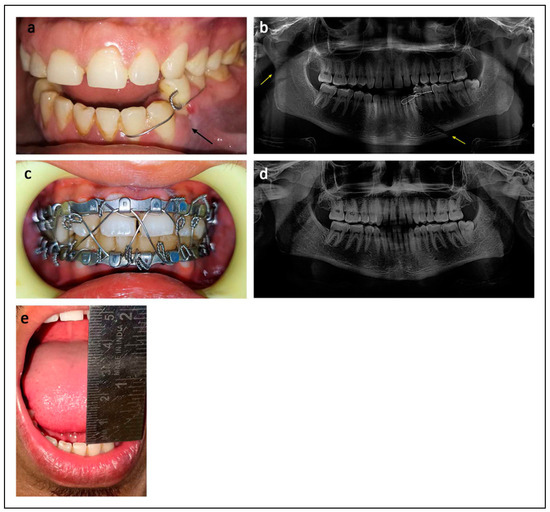

With respect to treatment provided, among the 476 (Group A) patients who reported with mandibular fractures during prelockdown period 77 (16.18%), patients were treated with ORIF while others were treated with closed reduction. All the patients with mandibular fractures except 16 (4.97%) in Group B were treated by closed reduction and IMF using Erich arch bar for 4 to 6 weeks depending on the number of fracture sites, age of the patient, and presence of teeth in the line of fracture (Figure 5). ORIF was only advised when displacement of fractures made prognosis of closed reduction unacceptable. Postoperative displacement or malunion of fractures was not observed in any of the patients clinically or radiographically. A comparison of 93 patients who underwent ORIF during the study period showed that during the initial 6 months after lockdown, that is, April 2020 to September 2020, no cases were treated using ORIF (Table 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Mandibular fracture treated by Closed Reduction. a. Intraoral photograph showing fracture of mandible between left canine and first premolar; b. Orthopantomogram (OPG) showing displaced left parasymphysis and right subcondylar fractures; c. Intraoral photograph showing closed reduction with IMF using Erich arch bar; d. Postoperative OPG showing healed mandible; e. Postoperative photograph showing adequate mouth opening.

Table 5.

Comparison of month wise number of patients who underwent ORIF as treatment of mandibular fractures.

Figure 6.

Line diagram corresponding to month wise number of patients who underwent ORIF as treatment of mandibular fractures in Group A (Light blue) and Group B (Dark blue).

GOHAI QoL Results

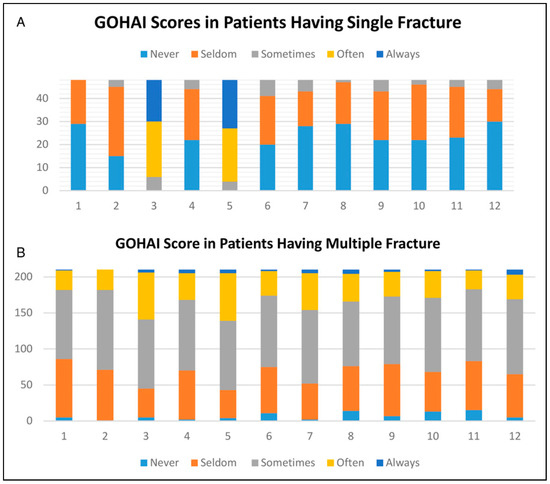

Three hundred and twenty-two patients reported to our department with trauma related fractures involving mandible during 10 months after lockdown from April 1st 2020 (Group B). Exclusive mandibular fractures occurred only in 284 patients with 226 having multiple and 58 having single mandibular fractures. Sixteen of these case who underwent ORIF as closed reduction was deemed impossible were excluded from the study. So the remaining eligible 268 cases (213 multiple and 55 single fracture cases) were contacted after 2 months of treatment to be part of the study assessing QoL using GOHAI questionnaire (Table 1). Two hundred and fifty eight patients, that is, 210 cases with multiple fracture and 48 with single fracture responded to the questionnaire.

The results of GOHAI QoL assessment showed that there was significant (P < .05) difference between the single and multiple fracture groups as expected, with patients having single fractures showing mostly favorable scores. When it came to patients with multiple fractures, score 3 (sometimes) were selected by most of the respondents followed by score 2, that is, seldom. There was general trend of favorable answers to questions pertaining about social factors indicating that the treatment had more of a physical impact. Association of fracture and gender showed significant result for questions 1 and 2 only (P < .05). Age groups did not show any significant relationship for any of the questions. When it came to etiology, only questions 3 and 4 showed significant relationship with post-hoc test showing mean difference (.034) between RTA and Assault. The details of GOHAI QoL assessment results are given in Table 6 and Figure 7a, b.

Table 6.

Distribution of frequency and percentage answers of the quality of life (GOHAI) of subjects with single (n = 48) & Mutiple (n = 210) mandible fractures. (*P < .05, Statistically Significant).

Figure 7.

a. Distribution of frequency and percentage answers of the quality of life (GOHAI) of subjects with single mandible fractures (n = 48). b. Distribution of frequency and percentage answers of the quality of life (GOHAI) of subjects with multiple mandible fractures (n = 210).

Discussion

After one and half years and recovering from the second wave of pandemic that hit the country, we have come to understand COVID-19 better and embraced better management protocol, thus reducing mortality significantly. Our understanding to treat trauma patient in times of pandemic has also been evolved. Though achieving the best functional and esthetic outcome for trauma patients were of paramount importance, the attention was also shifted to restrict aerosol generating procedures, so as to prevent any spreader events [11,12,13,14].

The present study evaluated the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on maxillofacial trauma and its treatment during 10 months nationwide lockdown in March of 2020 (Group B) which resulted in partial suspension of many planned surgical activities in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, MAIDS, New Delhi, India. Using retrospective data, we compared the demographics, etiology, and fracture pattern of these patients with those of patients reported 10 months before lockdown (Group A). The data thus obtained suggested that there was a significant drop in cases reported due to facial trauma in this time period. This was consistent with many studies done across the world during this time period [3,4,7].

Age group and gender ratio were almost similar in both groups, but etiology due to fall and assault in Group B showed a noticeable increase of 8.23% during lockdown period though RTA contributed to majority of the cases. Authors like Mazza et al. and Mittal et al. have found the impact of quarantine during pandemic on interpersonal and gender-based violence, but our study failed to find a strong association to such a trend [15,16]. This may be partially due to the exclusion of isolated midface fractures, dental, and soft tissue trauma in our study and/or due to the under reporting of such incidence in our society [17].

Canzi et al. and Ludwig et al. found that severity of trauma increased during pandemic times and the latter also noted that there was slight increase in trauma secondary to assault [4,5]. Similarly, our study also showed a slight increase in severity of fractures in Group B as we found approximately 17.81% increase in prevalence of multiple mandible fractures compared to Group A. With the data from 1333 fracture sites within mandible in 798 patients, we found that the most involved fracture site was parasymphysis (24.31%) with coronoid (.68%) being least involved. This pattern was consistent with similar studies within the country [18,19,20].

As the first wave of pandemic with subsequent lockdowns made profound impact on trauma management across the globe, the surgical community had no option but to completely or partially shut down most of the surgical procedures. As the world was trying to figure out the novel coronavirus, it became pertinent that a protocol for trauma management should be in place. Many authors have made their contribution for setting up such a protocol [2,7,21,22]. Similarly, in our institution, in spite of reduced resources and manpower, emergency department was functioning with the goal of continuing best practice and delivery of quality care. To reduce the amount of aerosol production and prevent spread, a protocol based on conservative or closed reduction was instituted for maxillofacial fracture cases unless deemed impossible. Though ORIF for fractures is considered the norm, closed reduction technique remains the age old, time tested method [23]. It is evident from our study that how much influence this pandemic had on our treatment protocol. During the initial 6 months after lockdown, no cases were treated with ORIF and only 16 patients underwent the same during the lockdown study period.

The assessment of the functional impact on QoL after 2 months of treatment in patients with mandibular fractures using GOHAI questionnaire showed that the patients with single mandibular fractures responded favorably while patients with multiple fractures had average response. While etiology of trauma and gender of patient had some significance on response to some questions of GOHAI QoL assessment, age of the patient was not a significant factor. The literature search on QoL with GOHAI assessment revealed that though research subjects responded favorably in the early days after using closed reduction, in the long follow-up, ORIF also provided similar results [9,24,25].

The study reveals that IMF remains as the gold standard for the management of most of the facial fractures in any pandemic situation. It was evident from the QoL data that most of the patients were able to carry out their day-to-day functions adequately which could be improved once pandemic is over by routine dental treatment. We were able to manage oral and maxillofacial trauma without cross-contamination by following the standard protocols set up during COVID-19 pandemic satisfactorily. The survey also showed that there was no significant change in demographic data and etiology except number of cases reported were reduced during lockdown. As the country prepares for a third wave of pandemic, management of maxillofacial trauma by closed reduction will remain the norm.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Clearance

This study is exempted from ethical clearance as it was a retrospective study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawhney, C.; Singh, Y.; Jain, K.; Sawhney, R.; Trikha, A. Trauma care and COVID-19 pandemic. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 36, S115–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishal, O.; Prakash, O.; Rohit, V.K.; Prajapati, V.K.; Shahi, A.K.; Khaitan, T. Incidence of maxillofacial trauma amid COVID-19: A comparative study. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, D.C.; Nelson, J.L.; Burke, A.B.; Lang, M.S.; Dillon, J.K. What is the effect of COVID-19-related social distancing on oral and maxillofacial trauma? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021, 79, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canzi, G.; De Ponti, E.; Corradi, F.; et al. Epidemiology of maxillofacial trauma during COVID-19 lockdown: Reports from the hub trauma center in Milan. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Reconstr. 2020, 14, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Health Organization Considerations for the Provision of Essential Oral Health Services in the Context of COVID-19: Interim Guidance, Geneva PP—Geneva: World Health Organization. 3 August 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/333625.

- Yeung, E.; Brandsma, D.S.; Karst, F.W.; Smith, C.; Fan, K.F. M. The influence of 2020 coronavirus lockdown on presentation of oral and maxillofacial trauma to a central London hospital. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 59, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, A. Molecular diagnostic technologies for COVID-19: Limitations and challenges. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 26, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchison, K.A.; Shetty, V.; Belin, T.R.; et al. Using patient self-report data to evaluate orofacial surgical outcomes. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2006, 34, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingman, R.O.; Navig, P. Surgery of Facial Fractures; Saunders, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Virdi, M.K.; Durman, K.; Deacon, S. The debate: What are aerosol-generating procedures in dentistry? A rapid review. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2021, 6, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, H.; Broom, A.; Broom, J. Aerosol-generating procedures and infective risk to healthcare workers from SARSCoV-2: The limits of the evidence. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 105, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, G.S. Aerosol-generating procedures in the COVID era. Respirology. 2021, 26, 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Z.-Y.; Yang, L.-M.; Xia, J.-J.; Fu, X.-H.; Zhang, Y.-Z. Possible aerosol transmission of COVID-19 and special precautions in dentistry. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2020, 21, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, M.; Marano, G.; Lai, C.; Janiri, L.; Sani, G. Danger in danger: Interpersonal violence during COVID-19 quarantine. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 289, 113046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Singh, T. Gender-based violence during COVID-19 pandemic: A mini-review. Front. Glob. Women’s Health. 2020, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadda, A.; Malik, J.S.; Rohilla, R.; Chahal, S.; Chayal, V.; Arora, V. Study of domestic violence among currently married females of Haryana, India. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2018, 40, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaurasia, A.; Katheriya, G. Prevalence of mandibular fracture in patients visiting a tertiary dental care hospital in North India. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 9, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhinav, R.; Selvarasu, K.; Maheswari, G.; Taltia, A. The patterns and etiology of maxillofacial trauma in South India. Ann. Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 9, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barde, D.; Madan, R.; Mudhol, A. Prevalence and pattern of mandibular fracture in Central India. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 5, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S.P.; Kasten, S.; Nelson, C.; Elner, V.; McKean, E. Maxillofacial trauma management during COVID-19: Multidisciplinary recommendations. Facial Plast. Surg. Assihelj Med. 2020, 22, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglia, F.A.; Hills, A.; Dawoud, B.; et al. Management of oral and maxillofacial trauma during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 59, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blitz, M.; Notarnicola, K. Closed reduction of the mandibular fracture. Atlas Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. 2009, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omeje, K.U.; Rana, M.; Adebola, A.R.; et al. Quality of life in treatment of mandibular fractures using closed reduction and maxillomandibular fixation in comparison with open reduction and internal fixation—A randomized prospective study. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2014, 42, 1821–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osunde, O.; Omeje, K.; Efunkoya, A.; Adebola, A. Oral health-related quality of life in non-surgical treatment of mandibular fractures: A pilot study. Niger. J. Exp. Clin. Biosci. 2015, 3, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2022 by the author. Multimed Inc.