Complicated Facial Lacerations: Challenges in the Repair and Management of Complications by a Facial Trauma Team

Abstract

Introduction

Materials and Method

Definition

- Large size (>10 cm);

- involving more than 2 facial zones;

- extensive skin avulsion or skin loss;

- involving any specialized facial structure (eyelid, nose, lip, or ear);

- involving neurovascular structures of the face; and

- involving glands or ducts.

Exclusion Criteria

Results

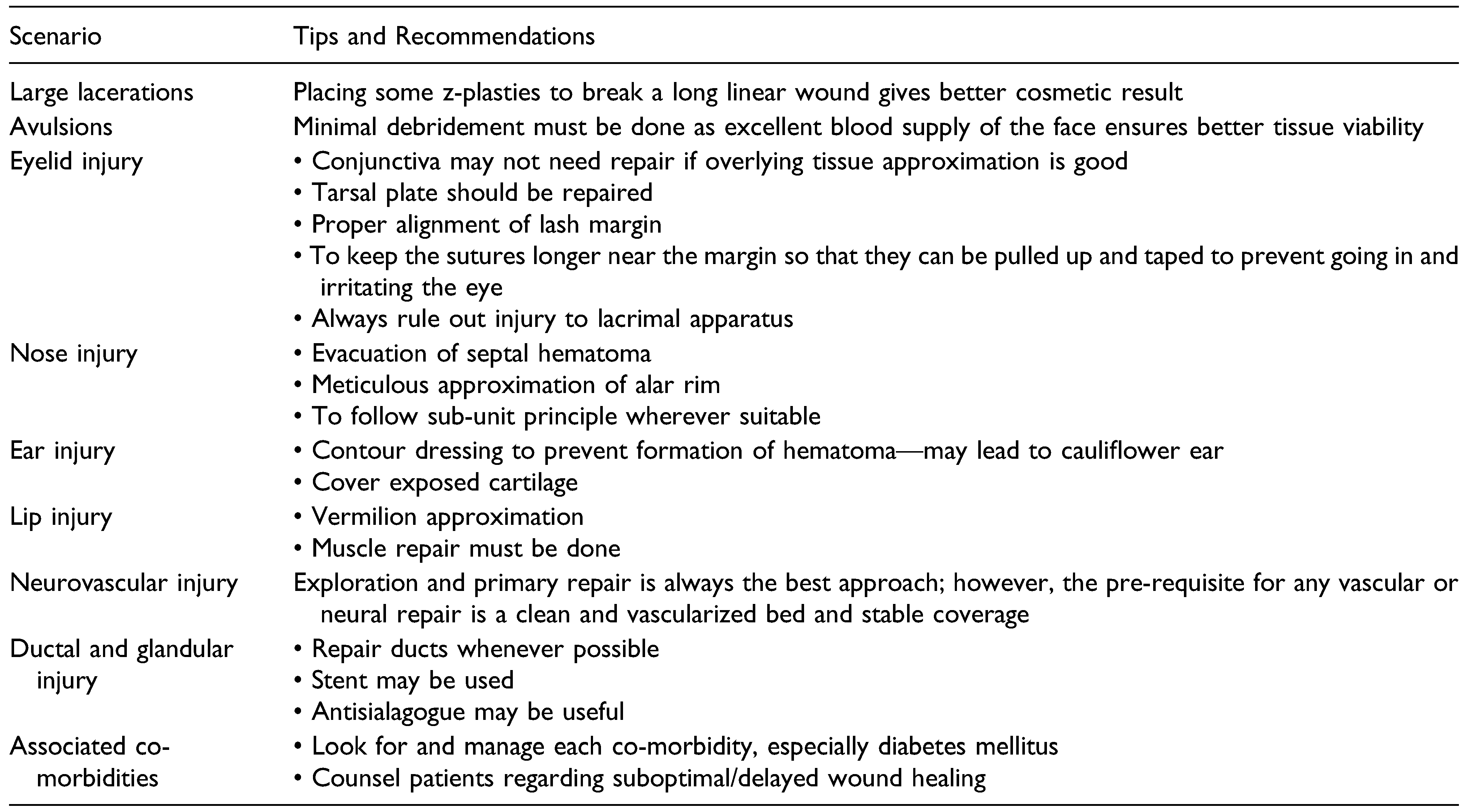

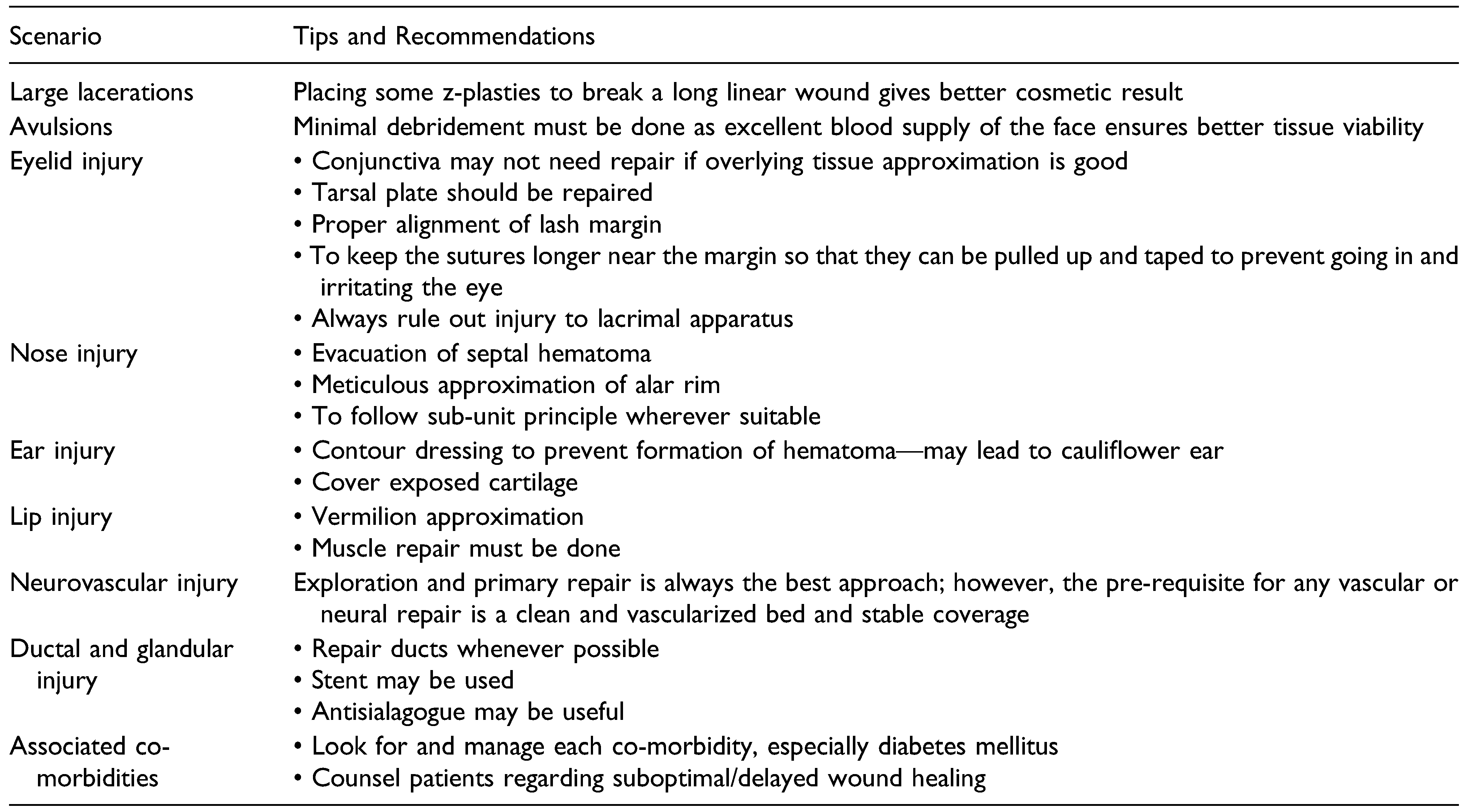

Scenario 1: Large Wound (>10 cm)

Challenges Faced and Steps Taken

- Involvement of multiple units: Involvement of the forehead, brow, eyelid, nose, and cheek entailed that each part was addressed according to the protocol prescribed for that unit. Knowledge of the subunits of face and reconstruction of each part was of paramount importance.

- 2.

- Underlying head injury: The fracture of the left frontal bone was managed conservatively by simple reduction alone. There was no underlying dural breach. However, the presence of head injury and altered sensorium precluded any thorough clinical examination of the facial nerve function.

- 3.

- Nasal bone fracture: Compound fracture of nasal bone was present but it was not amenable for any fixation. Therefore, it was managed conservatively by reduction of fragments, suturing of overlying skin, and splinting.

Scenario 2: Extensive Skin Avulsion or Skin Loss

Challenges Faced and Steps Taken

- Contamination: The injury being a road traffic incident, the wound was contaminated with dust and debris. Stone particles and tiny plastic fragments along with grass and soil were found embedded in the wound. The patient presented within 6 hours of injury. In the OR, thorough cleaning was done first with saline to wash away soil and debris. Then scrubbing was done with 4% chlorhexidine gluconate solution and copious saline wash was given. Finally, the wound was painted with a povidone iodine solution as per the institution OR protocol. The wound healed well in the post-operative period; however, the sutures were kept for 7 days instead of the standard 5 days in view of the grossly contaminated wound.

- Exposed frontal bone: A 1.5 × 2 cm area of the frontal bone was exposed with a small area of periosteal stripping. However, as the reposition of the avulsed flap was adequate to cover this exposed bone, no additional flap was required.

- Doubtful viability of avulsed skin: The avulsed skin flap had areas of friction burn and also the edges did not have healthy bleeding. However, owing to the excellent blood supply of the face, only minimal marginal debridement was done and tissues were preserved as much as possible. In the post-operative period, the entire skin survived without any necrosis.

Scenario 3.a. Involvement of Specialized Structures: Eyelid

Challenges Faced and Steps Taken

- Involvement of eyebrow: Proper alignment of the eyebrow was done matching the brow hairline to prevent notching of the eyebrow. An exact approximation was done with subcuticular sutures to prevent scar widening and possible future scar alopecia.

- Involvement of orbicularis oculi: Muscle was approximated with 4-0 vicryl horizontal mattress suture without any overlapping. Any overlapping or gap would cause animation deformity in this readily visible area.

- Comminuted skin laceration: The laceration was comminuted and had to be matched like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle to achieve exact approximation. Loupe magnification was used for meticulous repair (Figure 3B).

- Avulsed skin segments on narrow pedicle: Although skin segments were avulsed with very narrow attachments, no skin was debrided. Owing to the superior blood supply of this region, native tissue was preserved as much as possible.

Case #2

Challenges Faced and Steps Taken

- Full thickness eyelid defect with loss of support and exposed globe: The exposure of the globe was an emergency that needed intervention to prevent desiccation and corneal damage. The eyelid defect was meticulously repaired in layers from the deepest to the most superficial layer.

- Comminuted skin laceration with doubtful vascularity: The lid skin was repaired with 6-0 prolene under loupe magnification. Absolutely no tissue was debrided and discarded from the lid skin.

- Ruptured tarsal plate with loss of structural support of the lid: The ruptured tarsus was aligned meticulously with 5-0 prolene suture to reconstruct the support framework. Next the orbicularis muscle was approximated without any bunching or overlapping. The muscle closure effectively covered the tarsal plate and the sutures and provided additional support.

- Conjunctival laceration: The conjunctiva was repaired with 5-0 vicryl inverted sutures to not leave any exposed suture or knot over the corneal side.

- Involvement of other facial units: Other facial aesthetic units (cheek, nose, and lip) were repaired following the principles of reconstruction of that subunit (Figure 4B).

Scenario 3.b. Involvement of Specialized Structures: Auricle

Challenges Faced and Steps Taken

- Crush and avulsion of skin: The overlying lateral surface of the auricle was crushed and avulsed. However, the medial (posterior) surface skin was intact mostly. After minimal debridement, a meticulous approximation of the skin was done (Figure 5B).

- Exposure and fracture of cartilage: The crushed and damaged cartilage was debrided. All fragments that had an attachment to the posterior skin were left undisturbed. No suture was put through the cartilage. The skin approximation was adequate to cover all the cartilage.

- Contamination: The gross contamination present was a risk factor for chondritis. Thorough cleaning with chlorhexidine solution along with meticulous debridement was done to decrease the infection load. Systemic antibiotic as well as topical antibiotic cream were used as a prophylaxis.

Scenario 3.c. Involvement of Specialized Structures: Nose

Challenges Faced and Steps Undertaken

- Injury to the cartilage: Injury to the upper and lower lateral cartilages as well as the septal cartilage caused loss of structural support to the nose (Figure 6A). The septal cartilage was reduced back in position. No suture was passed through the cartilages. While the immediate outcome was good, this patient had a prolonged ICU stay in view of head injury. On follow-up, there was resorption of septal cartilage support with deformity of the nasal dorsum. The patient is scheduled for rhinoplasty at a later date.

- Injury to alar margin: Problem with alar margin approximation is due to the thick skin which is adherent to the underlying cartilage. It is difficult to mobilize the skin and therefore unyielding to any sort of tissue rearrangement. A proper approximation is required to prevent notching (Figure 6B).

- Injury to the nasal mucosa and nasal floor: Nasal mucosa and nasal floor were repaired using 5-0 vicryl sutures.

Scenario 3.d. Involvement of Specialized Structures: Lip

Challenges Faced and Steps Taken

- Mucosal breach: Mucosal injury was repaired in a watertight fashion using 4-0 vicryl.

- Muscle injury: Muscle alignment was very important as any gap present or even any overlapping will be readily visible on animation. As lips are one of the most mobile areas of the body, this becomes very evident during conversation. Muscles were approximated exactly using horizontal mattress sutures with 3-0 vicryl.

- Vermilion alignment: Vermilion is a specialized feature of the lip that cannot be mimicked by any other tissue. Even 1 mm notching of vermilion is apparent at conversational distance. Therefore, an exact approximation of the vermilion was done using the white roll as a guide. Tattooing of the points was done before infiltrating local anesthetic to prevent distortion (Figure 7B).

- Vascular issue: One-sided labial artery was found to be intact on exploration which ensured that the entire flap survived.

- Alveolar fracture with loss of teeth: No immediate intervention was done. The maxillofacial team put the patient under their follow-up for a dental implant at a later date.

Scenario 4: Involvement of Neurovascular Structures

Challenges Faced and Steps Taken

- Injury to the facial nerve: On clinical examination there was only mild weakness of the left buccinator. This could have been missed if thorough exploration was not done. As there is arborization between zygomatic and buccal branches of the facial nerve, any injury in either of these branches may not be easily identifiable.

- Parotid gland injury: Parotid gland injury poses a risk of parotid fistula and sialocele formation. It was managed by repairing the gland’s capsule and use of an antisialagogues in the postoperative period.

Scenario 5: Involvement of Glands and Ducts

Challenges Faced and Steps Taken

- Identification of parotid duct injury: Identifying a duct injury is often difficult. The typical location of the laceration raised suspicion. The distal end was easily identified by cannulating the parotid duct from its buccal opening using an intravenous cannula. The tip of the cannula was seen coming out through the wound. The proximal end was identified under magnification. Presence of droplets of clear parotid secretion helped in identification of proximal end (Figure 9B).

- Use of a proper stent: The tube part of an 18G IV cannula was found to be of adequate length and diameter in our case.

- Long linear laceration: The long straight laceration was broken by placing 2 small z-plasties to make the scar less conspicuous (Figure 9C).

Scenario 6: Laceration in a Patient With Comorbidities

Challenges Faced and Steps Taken

- Contaminated wound: Thorough lavage of the wound was done using copious saline, chlorhexidine solution and povidone iodine.

- Multiple co-morbidities:

- Morbid obesity: Mobilization of the patient in the post-operative period was extremely difficult. She was closely monitored by the dietician and physiotherapist.

- Diabetes mellitus (poorly controlled): The patient was a diagnosed diabetic on oral hypogylcemic agents for the last 6 years but her blood sugar was poorly controlled. During her admission, endocrinology consultation was taken and insulin injection was started in place of the oral medications. Fivepoint blood sugar monitoring was done and dose adjustment was done accordingly.

- Hypertension (uncontrolled): She was under irregular medication for hypertension previously. With opinion from internal medicine and cardiology, she was started on appropriate antihypertensive and antilipid medications.

- Hypothyroidism: She was previously diagnosed as a hypothyroid but was under irregular medication. Levothyroxine was started after endocrinology consultation

- Depression: Psychiatry consultation was done and she was put on an antidepressant and also followed up by the psychiatrist daily for behavioral therapy.

- Wound infection: She developed cellulitis and an abscess under the reposited flap on post-operative day 2 (Figure 10C, D). It was treated by re-exploration and abscess drainage with copious irrigation. Culture yielded polymicrobial infection. Antibiotics were started according to sensitivity report.

- Flap necrosis: The tip of the avulsed skin flap covering the lateral nasal wall was necrosed. The margin of the cheek flap was also necrosed. Debridement was done and the raw area was resurfaced with a full thickness skin graft (Figure 10D–G).

Discussion and Literature Review

Scenario 1

Scenario 2

- Contamination and a chance of infection.

- Doubtful vascularity of the avulsed skin segment.

Scenario 3.a. Involvement of Specialized Structures: Eyelid

Scenario 3.b. Involvement of Specialized Structures: Auricle

Scenario 3.c. Involvement of Specialized Structures: Nose

- extensive laceration;

- injury to the cartilage framework: ULC, LLC, and septal cartilage; and

- septal hematoma.

Scenario 3.d. Involvement of Specialized Structures: Lip

- To not obscure this very prominent part, especially in the upper lip.

- Suture through this part is shown to have a propensity for persisting inflammation.

- three-layer closure: mucosa, muscle, and skin;

- meticulous vermilion approximation; and

- muscle repair to be done in all cases, either partial or complete muscle transection.

Scenario 4: Involvement of Neurovascular Structures

Scenario 5: Involvement of Glands and Ducts

Scenario 6: Laceration in a Patient With Comorbidities

Other Published Guidelines and Proposed Algorithm for the Repair of Complicated Facial Laceration

Conclusion

Funding

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

References

- Yamamoto, R.; Homma, K.; Masuzawa, Y.; et al. Early complications following facial laceration repair performed by emergency physicians after one year of wound closure training. AEM Educ Train. 2018, 2, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badeau, A.; Lahham, S.; Osborn, M. Management of complex facial lacerations in the emergency department. Clin Prac Cases Emerg Med. 2017, 1, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri, S.C.; Dierks, E.J.; Kademani, D.; et al. Application of a facial injury severity scale in craniomaxillofacial trauma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006, 64, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Wang, W.; Geng, Y.; Shao, Y. Clinical experience in emergency management of severe facial trauma. J Craniofac Surg. 2020, 31, e121–e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kretlow, J.; McKnight, A.; Izaddoost, S. Facial soft tissue trauma. Semin Plast Surg. 2010, 24, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novelli, G.; Daleffe, F.; Birra, G.; et al. Negative pressure wound therapy in complex cranio-maxillofacial and cervical wounds. Int Wound J. 2018, 15, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Razak, N.; Nordin, R.; Abd Rahman, N.; Ramli, R. A retrospective analysis of the relationship between facial injury and mild traumatic brain injury. Dent Traumatol. 2017, 33, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.L.; Rubin PA, D. Management of complex eyelid lacerations. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2002, 42, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Goswami, S.C.; Baruah, D.K. Auricular trauma and its management. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006, 58, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kita, A.; Kim, I.; Ishiyama, G.; Ishiyama, A. Perilymphatic fistula after penetrating ear trauma. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019, 3, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrich, R.J.; Griffin, J.R.; Ansari, M.; Beran, S.J.; Potter, J.K. Nasal reconstruction? Beyond aesthetic subunits: A 15-year review of 1334 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004, 114, 1405–1416.discussion 1417-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zide, B.M.; Swift, R. How to block and tackle the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998, 101, 840–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D. Reliable method for closing lacerations across the vermilion border of the lip. Can Fam Physician. 1998, 44, 47–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.; Maconochie, I. Should we glue lip lacerations in children? Arch Dis Child. 2003, 88, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Shafaiee, Y.; Shahbazzadegan, B. Facial nerve laceration and its repair. Trauma Mon. 2016, 21, e22066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordin, E.; Lee, T.S.; Ducic, Y.; Arnaoutakis, D. Facial nerve trauma: Evaluation and considerations in management. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Reconstr. 2015, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.; Rosenthal, E. Static and dynamic repairs of facial nerve injuries. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin. 2013, 25, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myckatyn, T.M.; Mackinnon, S.E. The surgical management of facial nerve injury. Clin Plast Surg. 2003, 30, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci Volpato, L.; Medeiros Paz, A.L.; Caetano, R.S. Borges Reconstruction of the parotid duct. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2018, 8, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.; Knottenbelt, J.D. Parotid duct injury: Is immediate surgical repair necessary? Injury. 1991, 22, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloosi, S.N.; Khoshnaw, N.; Ali, S.M.; Muhammad, B.A. Surgical management of Stenson’s duct injury by using double J stent urethral catheter. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015, 17, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lewkowicz, A.A.; Hasson, O.; Nahlieli, O. Traumatic injuries to the parotid gland and duct. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002, 60, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öztürk, M.B.; Barutca, S.A.; Keskin, E.S.; Atik, B. Parotid duct repair with intubation tube: Technical note. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2017, 7, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winstead, M.L.; Clegg, D.J.; Heidel, R.E.; Ledderhof, N.J.; Gotcher, J.E. Fall-related facial trauma: A retrospective review of fracture patterns and medical comorbidity. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021, 79, 86431209–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aita, T.G.; Pereira Stabile, C.L.; Dezan Garbelini, C.C.; Vitti Stabile, G.A. Can a facial injury severity scale be used to predict the need for surgical intervention and time of hospitalization? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018, 76, e1–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semer, N. Practical Plastic Surgery for Nonsurgeons; Authors Choice Press: Lincoln, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino, F.; Moskovitz, J.B. Facial wound management. Emerg Med Clin. 2013, 31, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D.J.; Jaffe, J.E.; Henson, J.K. Advanced laceration management. Emerg Med Clin. 2007, 25, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

© 2022 by the author. The Author(s) 2022.

Share and Cite

De, M.; Sagar, S.; Dave, A.; Kaul, R.P.; Singhal, M. Complicated Facial Lacerations: Challenges in the Repair and Management of Complications by a Facial Trauma Team. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2023, 16, 39-54. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211064512

De M, Sagar S, Dave A, Kaul RP, Singhal M. Complicated Facial Lacerations: Challenges in the Repair and Management of Complications by a Facial Trauma Team. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2023; 16(1):39-54. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211064512

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe, Moumita, Sushma Sagar, Aniket Dave, Ruchi Pathak Kaul, and Maneesh Singhal. 2023. "Complicated Facial Lacerations: Challenges in the Repair and Management of Complications by a Facial Trauma Team" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 16, no. 1: 39-54. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211064512

APA StyleDe, M., Sagar, S., Dave, A., Kaul, R. P., & Singhal, M. (2023). Complicated Facial Lacerations: Challenges in the Repair and Management of Complications by a Facial Trauma Team. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 16(1), 39-54. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211064512