Materials and Methods

991 patients with facial bone fractures were included in the study who reported to our unit between 2006–2016. Associated Injuries were correlated with gender, mechanism of trauma, and fracture site. All soft tissue injuries were excluded from the study.

Associated injuries were sub-classified under head injury, limb injury, clavicle fracture, rib fracture, cervical spine injury, and others. The mechanism of trauma was subclassified into road traffic accidents, fall, assault, and others. The fracture site was sub-classified into mandibular, zygomaticomaxillary, midface, frontal, nasal, and others.

Results

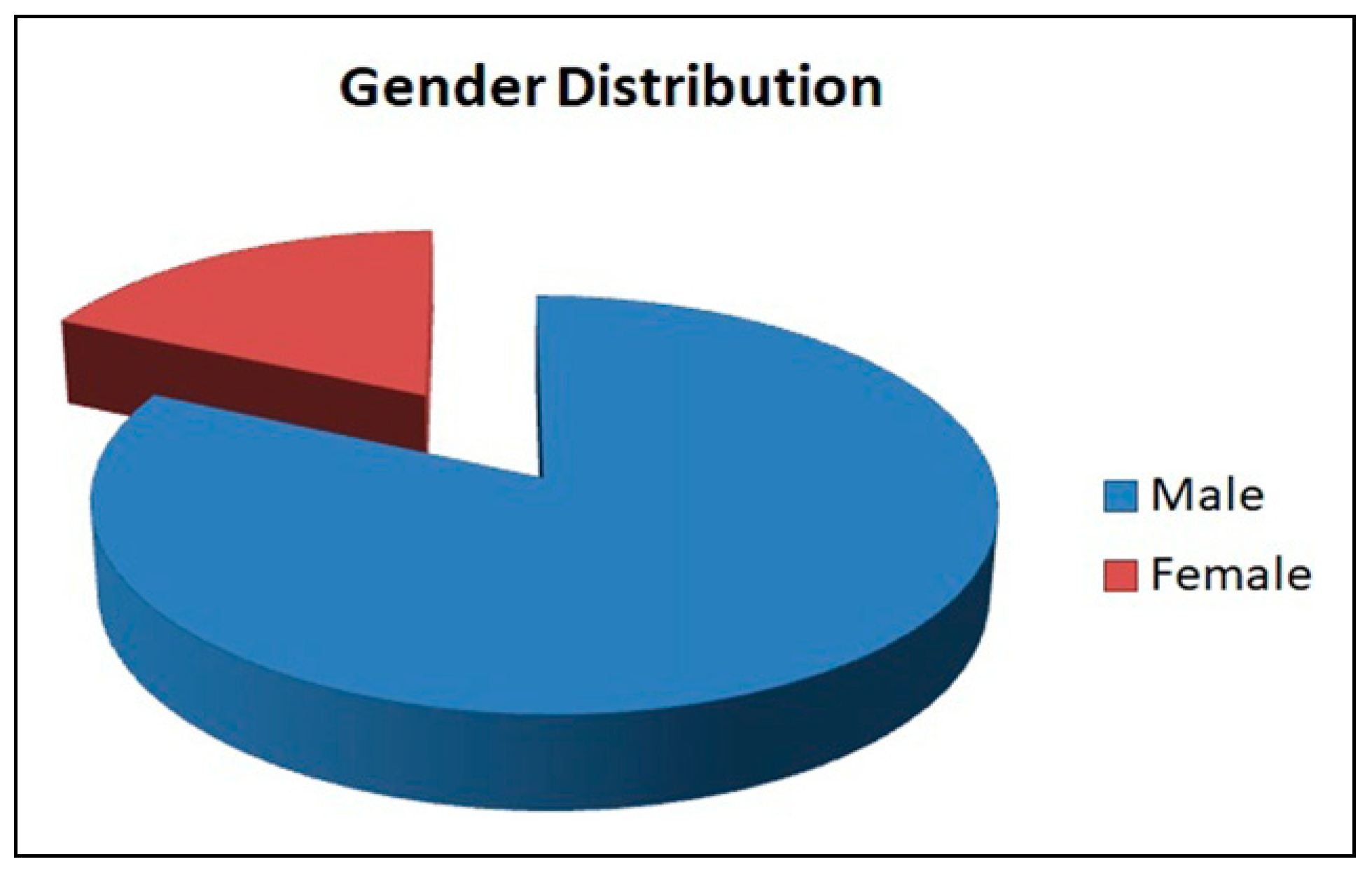

Among the 111 patients with facial fractures having associated injuries, 91 were male and 20 were female (

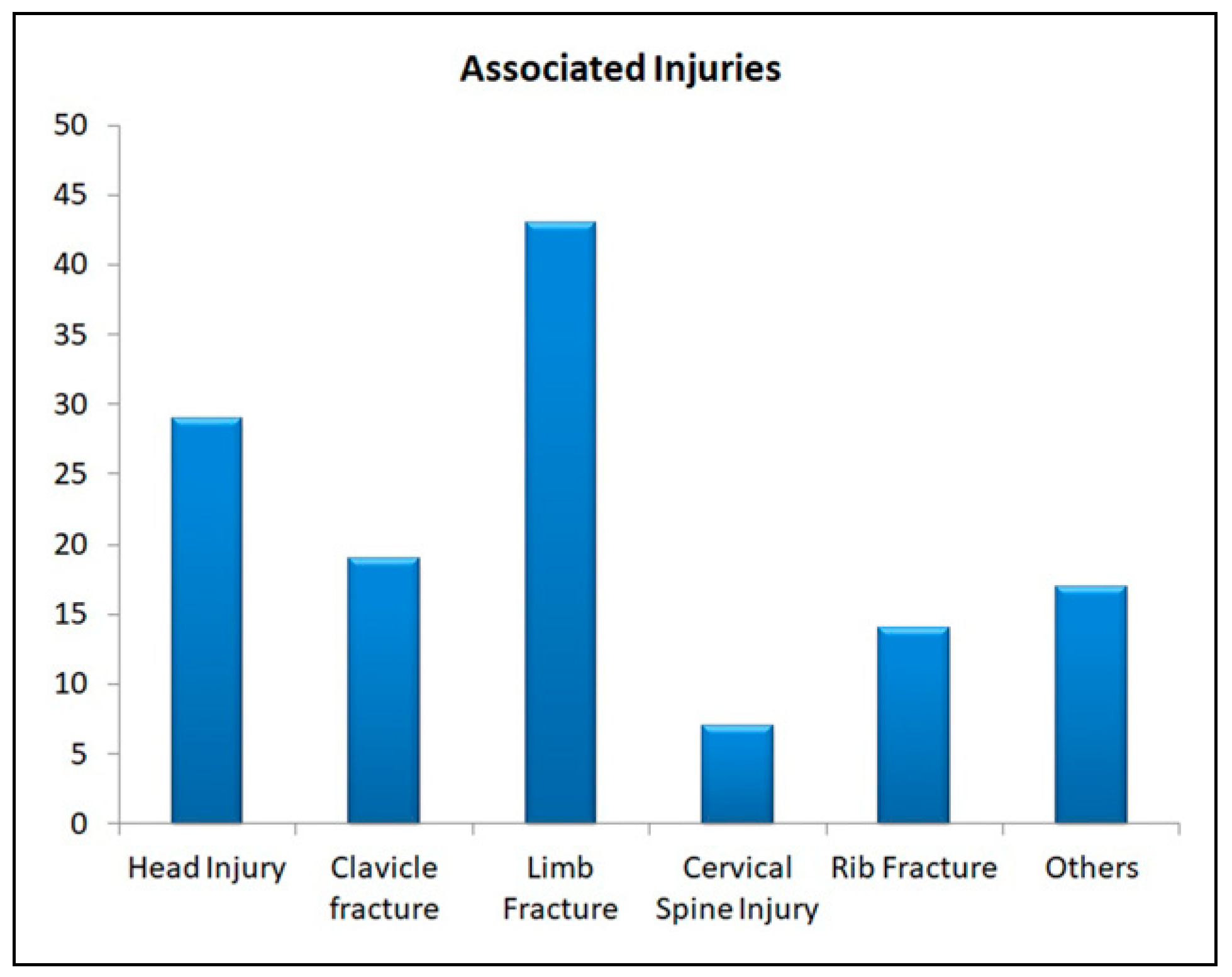

Figure 1). 18 patients had more than one associated injury. A total of 129 (13%) associated injuries were seen in these patients and among them, limb injury was most common (33.3%), followed by head injury (22.5%), clavicle fracture (14.7%), rib fracture (10.9%) and cervical spine injury (5.4%). Other injuries constituted roughly 13.2% of the remainder (

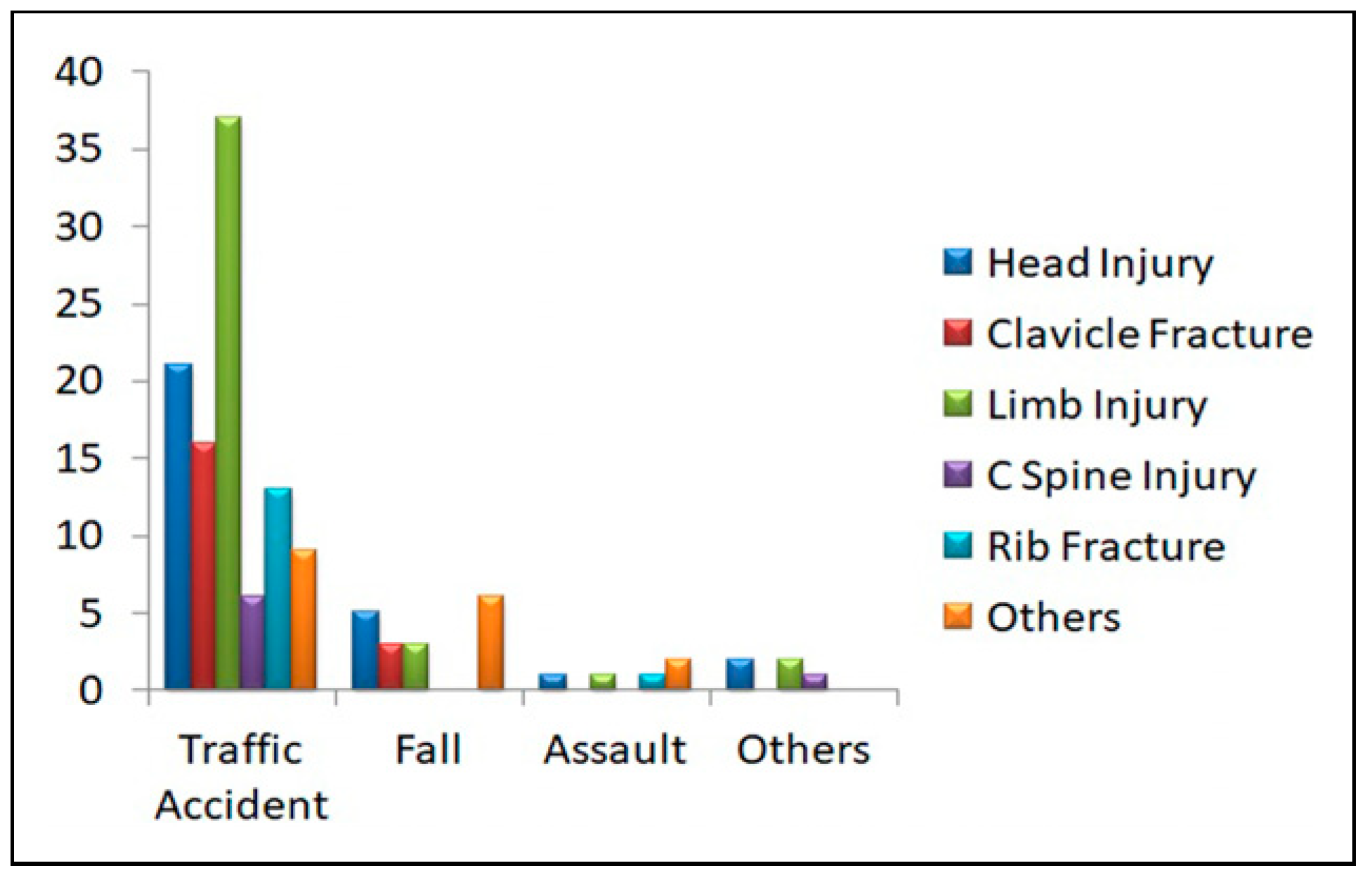

Figure 2). When the associated injuries were compared with different etiologies it showed that road traffic accidents were the most commonly related with different associated injuries in patients with facial fractures (67.4%), followed by fall (18.6%) and assault (7.8%) respectively. Other etiologies like industrial and sports constituted 6.2% of the remaining injuries.

Further distribution of the etiological factors with different associated injuries showed that among road traffic accidents limb injury was the commonest (42.5%), followed by head injury (24.1%), clavicle fracture, rib fracture, and cervical spine injury followed respectively. In patients having facial fractures due to falling head injury was the commonest (41.7%), clavicle and limb injuries followed respectively. Assault patients accounted mostly for head injury (40%), followed by limb injury and rib fractures. The entire correlation of different etiologies with various associated fractures is illustrated in

Figure 3.

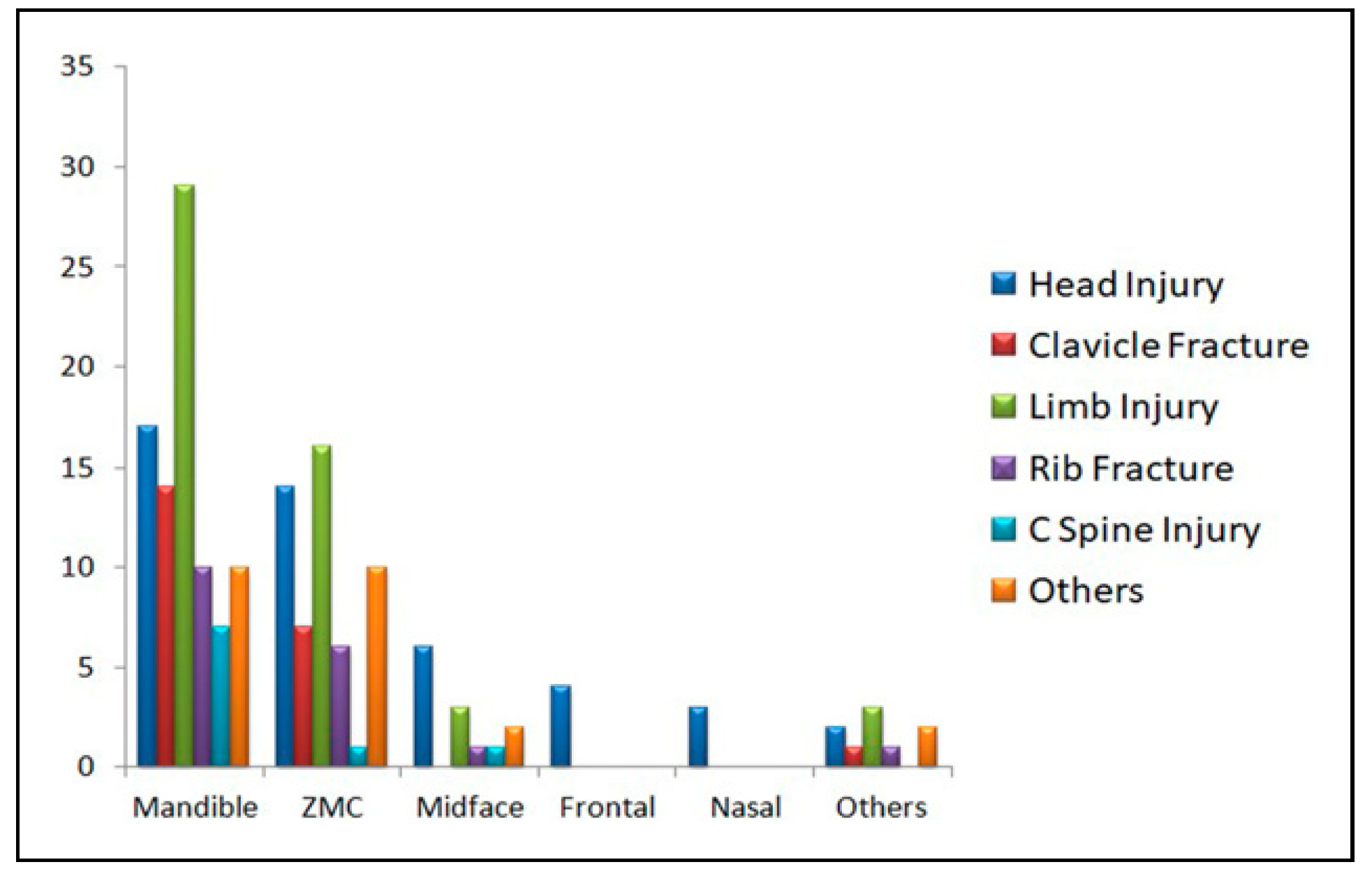

Mandibular fractures were most commonly associated with associated injuries (67.4%) and among the different injuries, limb injuries are most common followed by head injury, clavicle fracture, rib fracture, and cervical spine injury. Zygomaticomaxillary (ZMC) fractures were the second most common type of fracture that was related to associated injuries (41.9%). In this category also limb injury was commonest followed by the same pattern as seen in mandibular fractures. Midface fractures were the next common fracture type associated with other injuries (10%). In this category head injury was commonest followed by limb injury, rib fracture, and cervical spine injury. Frontal and Nasal bone fractures only had a head injury as associated injuries. Other fractures related to associated injuries constituted 7%. The entire correlation of various associated injuries with different types of fractures is illustrated in

Figure 4.

The average hospital stay for a patient with maxillofacial fracture solely was 2–3 days depending on the severity but the average stay increased to almost 3 times that s 10–12 days in patients having associated injuries along with maxillofacial fractures.

Discussion

Associated injuries were observed in our study to be 11.1% of all the facial fractures that were reported to our unit during this 10-year analysis. The incidence is quite low when compared to studies done by Thoren et al, Fischer et al, and Folmer et al [

2,

3,

4]. The explanation for this discrepancy is because the above-mentioned studies were mostly conducted in an emergency trauma center or primary trauma center whereas our unit is a tertiary maxillofacial center where patients report after getting the primary care of trauma. As a result, most of the data that were gathered was from patient medical records which might cause certain variations.

The most common associated injury in our study is limb injury (33.3%) which is quite similar to the study done by Thoren et al, Ajike et al, Punjabi et al, and Akama et al. [

2,

5,

6,

7]. The next common orthopedic injury in our study was clavicle fracture (14.7%) which was similar to the study done by Patil et al. [

8]. Previous studies have always focused on only life-threatening injuries associated with facial fractures which have overlooked injuries of limb, clavicle, and chest as a result data and correlation of these injuries with facial fractures are scarce. The pattern of impact and the way the patient fell has a very important correlation with these injuries. For example, patients with the etiology of fall showed a higher incidence of clavicle fracture compared to limb injuries mostly because while falling the hands were outstretched which is a natural reflex while falling causing a direct impact on the clavicle.

Life-threatening injuries like cerebral trauma, massive hemorrhage, airway obstruction are caused by high-speed trauma which was seen in 6% of patients according to Tung et al. [

1]. The single most life-threatening injury in our study was a head injury which was quite similar to the study done by Tung et al. [

1]. Another study done by Keenan et al [

9]. showed that in patients who have undergone simple bicycle accidents, the risk of intracranial injury was 10 times more in those having facial fractures compared to those who did not have facial fractures. These study results were quite contrary to the previous theoretical belief that facial bones absorb traumatic forces and thus reduces the chances of intracranial injury. So, it can be said that facial bone fractures are markers for increased risk of brain injury rather than being protective [

2]. Head injury incidence in our study was 22.5% which was similar to the study done by Thoren et al. [

2]. Head injuries were most common in patients with road traffic accidents and those patients having both mandibular and midface fractures rather than in isolated cases. Isolated cases of frontal and nasal bone fractures showed more severe head injuries which are similar to a study done by Hohlreider et al. [

10].

Patients with facial fractures had a small but real risk of cervical spine fracture [

2]. The overall incidence of cervical spine injury in our study was 5.4% among all patients with associated injures, which is close to the study done by Thoren et al. [

2]. The overall spine injury rate among all patients with facial fractures in our study is .8% which is within the range of figures presented by different other studies analyzing only cervical spine injuries in patients with facial fractures (.8%–3.7%) [

11,

12,

13]. The cervical spine injury was most commonly associated with patients involved in road traffic accidents [

11,

12,

14]. These patients constituted 4.7% of the total incidence of cervical spine injury. Clinical diagnosis of cervical spine injuries is difficult because these injuries do not present with local signs and symptoms [

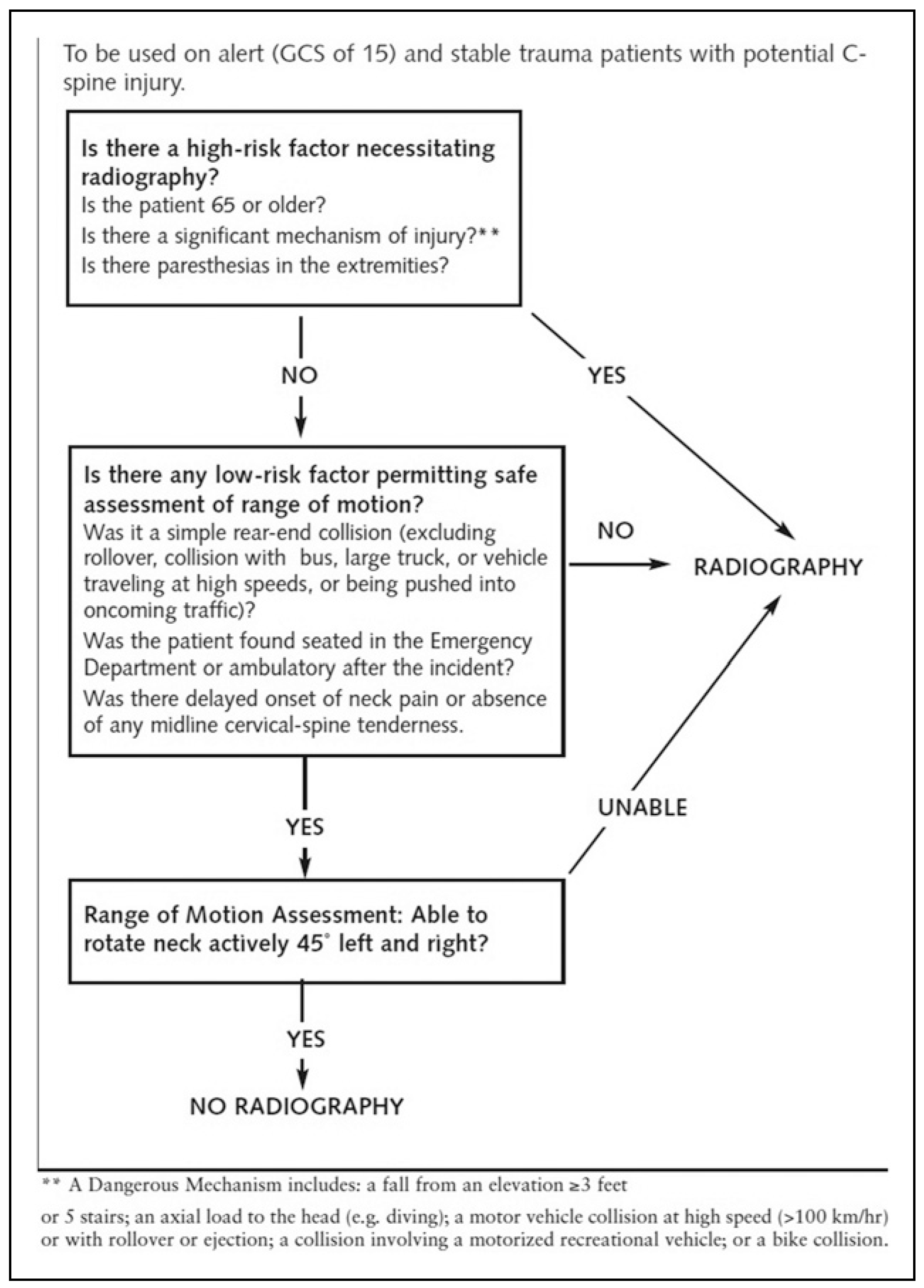

2]. Diagnostic tools such as CAT scans and MRI are ideal to identify cervical spine injuries but these tests create a lot of financial burden on the patient as well as many small hospitals in rural areas do not have the infrastructure to install such machines. In such a scenario implementing the National Emergency X-Radiography Study (NEXUS) or Canadian Cervical Spine Rule (CCR) can safely rule out patients for cervical spine injury thus significantly reducing the amount of unnecessary cervical imaging [

15].

NEXUS criteria state that the patient should be subjected to cervical spine imaging if it does not meet one of the following criteria: Absence of posterior midline cervical spine tenderness, No evidence of intoxication, A normal level of alertness and consciousness, Absence of focal neurological deficit, and Absence of any distracting injuries [

15]. The CCR criteria are explained as a flowchart in

Figure 5 [

15]. Although CT scan and MRI remain the gold standard in diagnosing cervical spine injuries these clinical assessments can be an ideal tool in rural areas and also can alert the physician while ambulating the patient for further diagnostic imaging and primary treatment.

Mortality rates were very low as per studies done by Thoren et al [

2]. and Tung et al [

1]. which reported .2% and .5%, respectively. Our study did not report any mortality as most cases were reported to our unit after the patient was treated for life-threatening injuries but significant morbidities were recorded in these patients. The lower rate of mortality may be mostly because approximately 50% of the patients with such high-speed trauma die on the scene or after arrival at the primary trauma center [

16]. As a result half of the patients do not reach the maxillofacial surgeon at all, contributing to an underestimation of the true mortality rate in studies arising from databases maintained in maxillofacial units [

2].

Life-threatening injuries were treated first in the primary center and once the patient was stable it was referred to the oral & maxillofacial surgery department for the treatment of concomitant maxillofacial fractures as a result there was a significant delay in facial fracture management and longer hospital stay for these patients compared to those having only maxillofacial injuries. A similar study was done by St Hilaire et al [

17] also states that facial fracture patients with associated injuries had a prolonged hospital stay and significant delay in starting facial fracture treatment.