Introduction

On March 11, 2020 the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome CoronaVirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) a pandemic, causing the COrona VIrus Disease-19 (COVID-19).[

1] Now, more than a year later, the world is still struggling to fight its consequences and to control the damage.[

2] The pandemic has drastically affected human lives and the way we conduct health services.[

3,

4,

5,

6] The world population was confronted with many abrupt life modifications such as mandatory mask wearing, staying at home, social distancing, and lockdown measures.[

7,

8] Although vaccines against the SARS-CoV-2 (SC-2) have been developed relatively quickly and most countries have already started to vaccinate, there are globally relevant regional differences in vaccination status.[

9,

10]

While in many parts of the world, nation-wide lockdown periods forced people to stay at home and to work from home, this was not possible for health care workers (HCWs) being active on the frontline to counter the COVID-19.[

11] HCWs were faced with major complex challenges such as high workload, changed protocols, and above all, avoiding exposure to SC-2.[

11,

12] Some HCWs were at higher risk regarding to SC-2 exposure because of aerosol-generating procedures. Aerosol transmission is believed to be one of the main spreading mechanisms of SC-2.[

13,

14] Craniomaxillofacial (CMF) surgeons work in the oral-/oropharyngeal area, where the viral load is relatively high and SC-2 is believed to replicate continuously.[

15] When CMF surgeons use power or diathermic instruments, aerosols are formed that may be contaminated with viral particles making providers vulnerable to aerosol transmissible diseases.[

16,

17] Because SC-2 had an abrupt advance, many health authorities were not prepared for changing protocols and the demand for personal protective equipment (PPE). This resulted in a shortage for PPE.[

18] Inadequate use of PPE could increase the risk for occupational exposure to SC-2 and development of COVID-19.[

19] Another effect of COVID-19 on health care is that many health care providers have paused elective treatments for a long time.[

16,

20] Elective procedures were rescheduled until safe strategies were identified to limit occupational exposure.

The “Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen” (AO) CMF is an international leading organization that serves surgeons and health care professionals. An international task force was created by the AO CMF leadership to develop and disseminate recommendations for best surgical practices during the COVID-19 pandemic, including a guideline with clear recommendations for CMF surgeons and the use of PPE.[

20] Furthermore, a survey was conducted by this taskforce to measure and describe how COVID-19 has affected and disrupted CMF patient care and to determine if there were geographic differences.[

21] A secondary purpose was to measure the adequacy of PPE and to identify factors that may limit access to adequate PPE.[

21] The study concluded that COVID-19 had a negative impact on CMF surgeons, their clinical practice, and personal life.[

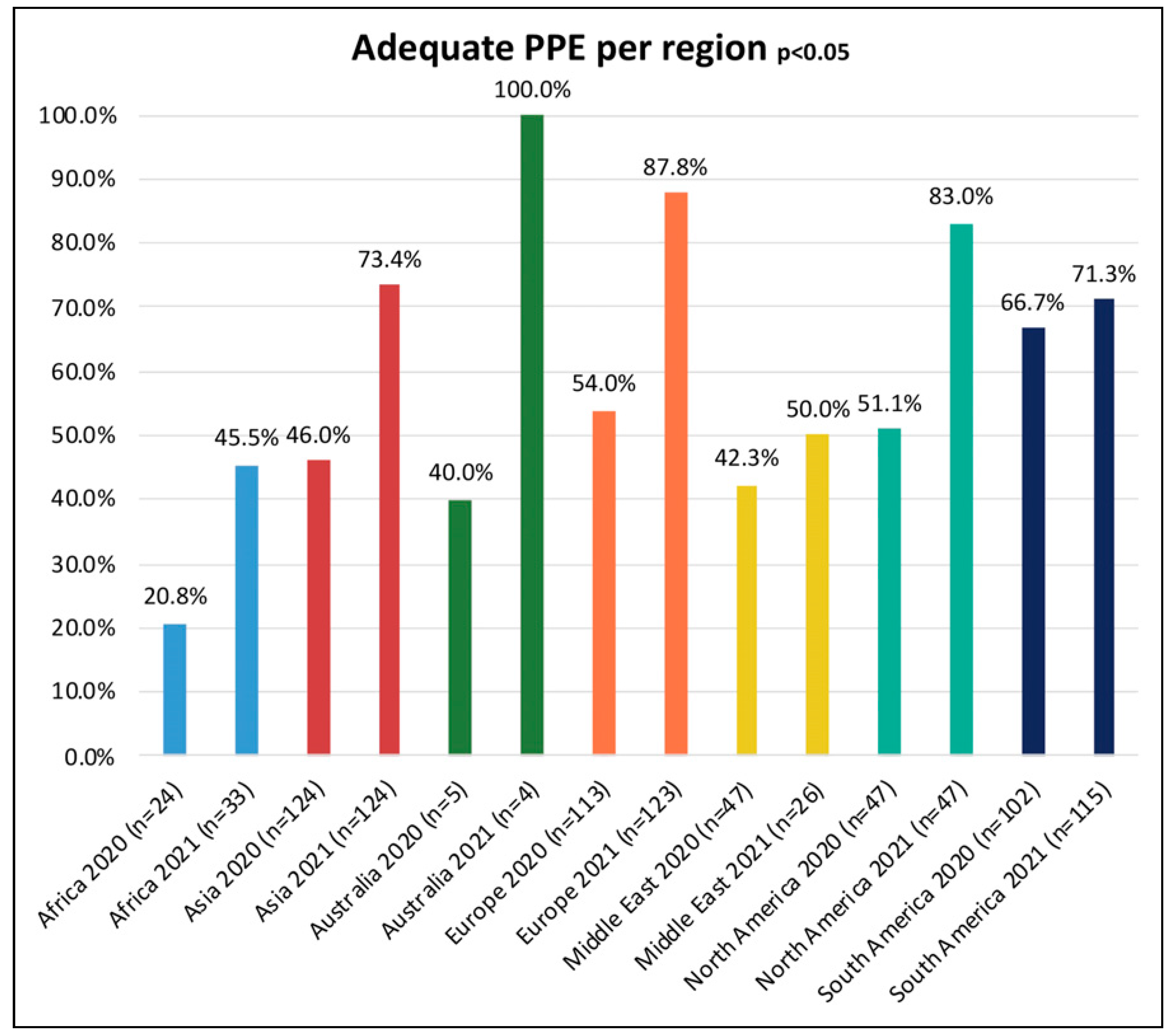

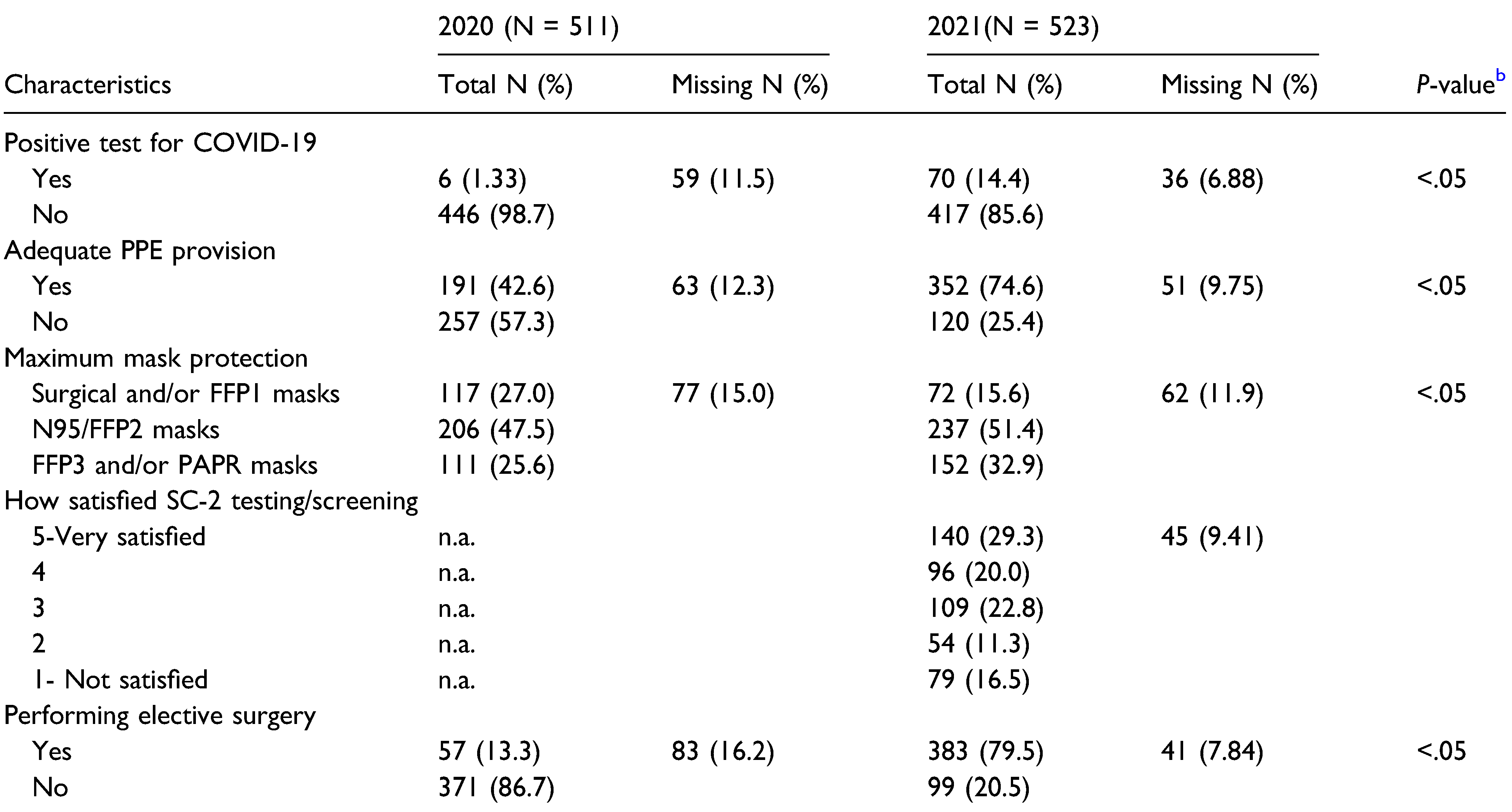

21] Most respondents (57.3%) felt that hospitals did not provide surgeons with adequate PPE with significant regional differences (

P = .04).[

21]

The aim of this study is to measure the impact of COVID-19 on CMF surgeons 1 year after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and compare the results with the study of 2020.[

21] We want to measure regional differences in PPE availability. Furthermore, we want to measure changes in elective CMF surgery during this year and the vaccination status per region. We hypothesize that most CMF surgeons are now provided with adequate PPE and SC-2 test availability. We expect that most CMF surgeons have still delayed elective treatments and that most have not yet been vaccinated. The specific aims of this study are to design, disseminate, and collect a survey among CMF surgeons (AO registered members), compare changes in time and to compare changes among geographic regions. The availability of PPE is our main focus since most CMF surgeons felt that hospitals did not provide them with adequate PPE. Inadequate PPE could increase the risk for occupational exposure to SC-2 and the development of COVID-19. If COVID-19 or a similar global threat arises again, this information may be useful as a reference, not only for this specialty, but also for other providers.

Methods

Ethical Approval

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles as stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.[

22] The study protocol has been approved by the medical ethical committee of the Erasmus Medical Centre in Rotterdam, the Netherlands (MEC-2020-0330 and MEC-2020-0330-A-0001). Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting of our study.

Study Design

The investigators designed a comparative cross-sectional study.

Study Population and Sample

The study population was composed of the international community of CMF surgeons registered in the database of AO CMF. The original survey was sent out on April 8, 2020. The new survey was distributed on March 31, 2021, the AO CMF community (N = 26 369) received an invitation via an email from AO CMF headquarters in Davos, Switzerland, to participate in the survey. On April 12, 2021, a reminder was sent. The survey was closed on April 16, 2021. The final sample was composed of CMF surgeons who returned surveys to the investigators. By completing the survey, the participants gave written informed consent to use their anonymized data for research, according to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) Recommendations for the Protection of Research Participants.

Survey Administration

The survey was administered digitally 1 year after the WHO declared COVID-19 as a pandemic. The completed surveys were collected, deidentified, and registered by AO CMF staff in Davos, Switzerland, in April 2021. The data were sent for statistical analysis to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Survey Construction

In this study, the investigators modified the van der Tas et al.[

21] survey that was distributed in 2020. The original survey was adapted from the survey used by AO Spine to evaluate the global impact of COVID-19 on spine surgeons and other specialists.[

21] For the current study, we removed 53 questions from the van der Tas survey and we added 6 questions about vaccination status. The final survey contained 30 questions distributed over 5 domains: general demographics, overall impact of COVID-19, vaccination status, patient care, and PPE. The complete questionnaire is available in the supplementary material (Supplementary material S1).

The primary predictor variable was the year of the survey administration. The secondary predictor variable was geographic region grouped as Africa, Australia, Asia, Europe, Middle East, North America, and South/Latin America.

The primary outcome variable was defined as the respondents’ perception of whether there is adequate PPE available for surgeons (coded yes/no).

The secondary outcome variables were the performance of elective surgery (coded yes/no) and vaccination status (coded as fully/partly or not vaccinated). The survey consisted mainly of multiple-choice questions and can be found in the online supplementary material.

Domain—General Demographics and Variables

The respondent’s sex was categorized as female or male. Age was grouped into 5 categories: 25–34 years, 35–44 years, 45–54 years, 55–64 years, and 65 years and older. The respondents could choose from different specialties; oral and maxillofacial surgery, plastic surgery, ear, nose, and throat (ENT), head and neck surgery, ophthalmology, neurosurgery, level of training (faculty/resident) for the previous mentioned specialties, and other. Respondents were asked about their practice type, which was categorized as academic/university hospital, private, academic/private combined, or public local hospital. Moreover, they were asked about previous health outbreaks which affected their practice and training, and the responses were coded as none, SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome), Swine Flu (H1N1), MERS (Middle-East Respiratory Syndrome), or EBOLA disease. Other questions included SC-2 quarantine status past year (yes/no), SC-2 test availability (on a numeric scale from 1 to 5 [1: not satisfied, 5: very satisfied]), and if they were performing elective procedures (yes/no). Vaccine availability in their country (yes/no), vaccination status, the obligation to get vaccinated (yes/no), and acceptance of unvaccinated colleagues (yes/no) was also asked. At last, the respondents were asked which maximal PPE was available. The PPE choices were none, FFP1 mask (Filtering Face Piece 1), N95/FFP2 mask, FFP3 mask, PAPR (powered-air purifying respirators), surgical mask, face shield, gown, full-face respirator, and other. Respondents were also asked whether they perceived that there was sufficient PPE (yes/no).

Statistical Analysis

For each study variable, descriptive statistics were computed. Sample characteristics are presented for each category with their corresponding number of participants and their percentages, based on the number of valid cases. Bivariate analysis was computed to measure the association between the availability of adequate PPE for surgeons and the study variables. To assess this, a Fisher’s exact test (Monte Carlo method 99% confidence interval [CI] because a cell count was lower than 5 in some cases) was used. The availability of adequate PPE, the maximal mask protection, vaccination status, and whether elective surgery was performed were graphically visualized in a bar plot stratified per region. Differences in distribution were tested by a Chisquared test, a Fisher’s exact test, or a one-way ANOVA test when variables were not dichotomous. Furthermore, binary logistic regression models were built to assess the influence of year on the own view of availability of adequate PPE for surgeons. In the first model, no adjustment was made for any variable. In the second model, the association was adjusted for age, specialty, and to whether there have been previous virus outbreaks in the region. Missing data of the included variables were imputed using a multiple imputation method (chained equations or the Markov chain Monte Carlo [MCMC] method), except for the exposure and outcome variables. The imputed data sets were pooled, and the results of the logistic regressions were presented as odds ratios (ORs) with their 95% CIs. The analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences SPSS V.25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA, 2017) for Mac iOS. For all analyses, statistical significance was set at a P-value <.05.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine PPE availability for surgeons after 1 year of dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic and to compare it to the data of 2020. We also studied the clinical impact on elective CMF surgery during this year and vaccination status per region.

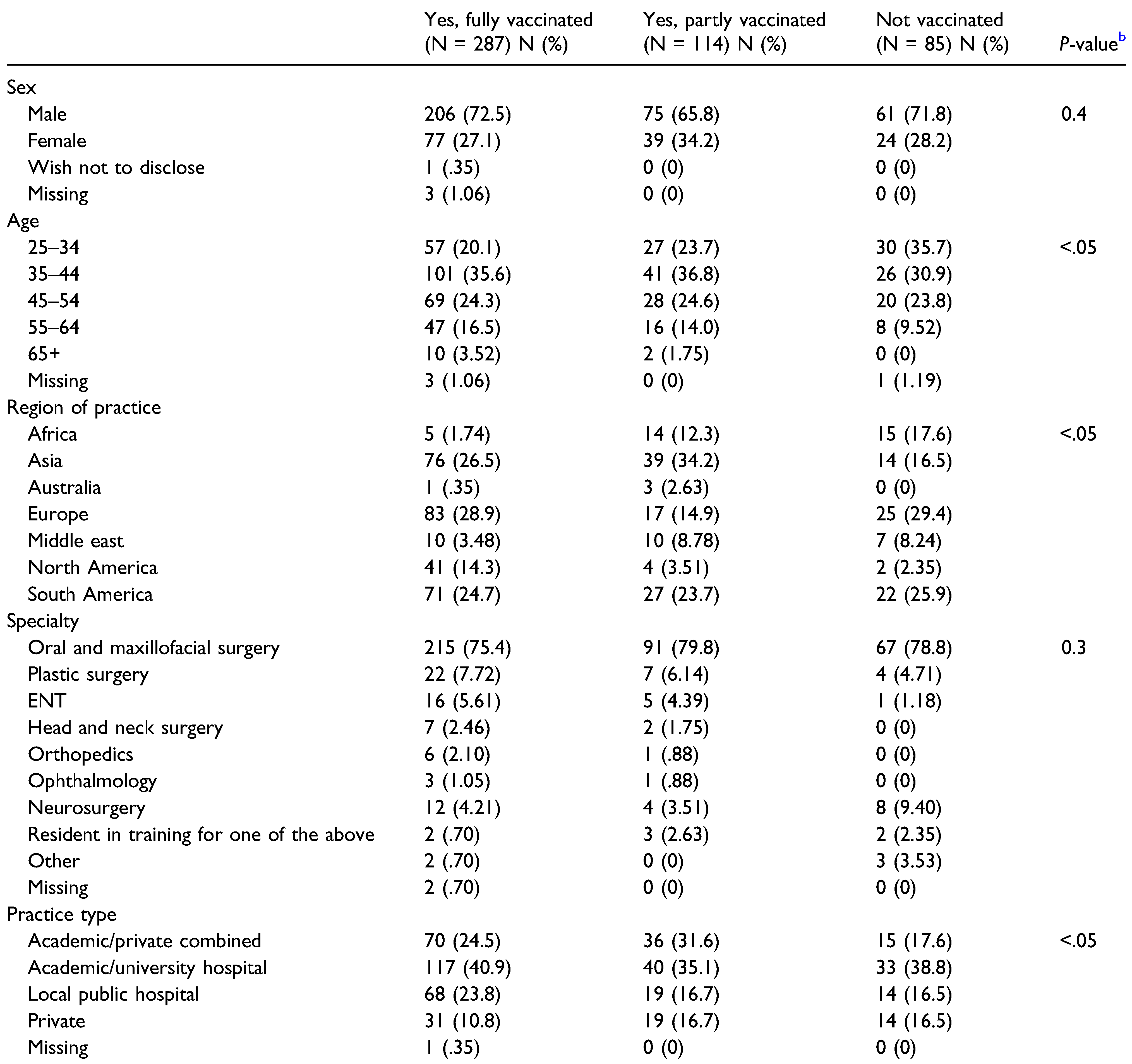

We found the vast majority of the AO CMF community globally feels the hospitals provide adequate PPE to surgeons in contrast to the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, though we noticed regional differences. Second, the availability of PPE under surgeons considerably varied per region. Third, most of the CMF surgeons restarted performing elective surgery. Lastly, most of the CMF surgeons were either fully or partly vaccinated.

Surgeons are at the front line of the COVID-19 outbreak response and are exposed to the risk of infection and CMF surgeons are in a greater risk due to aerosol-generating procedures.[

14,

15,

17] As proposed by WHO for all surgeons and AO CMF for surgeons active in the CMF field, hospitals must take responsibility to ensure that all necessary preventive and protective measures must be taken to minimize health risks concerning infection.[

20,

23] At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the majority of CMF surgeons felt the hospitals did not provide adequate PPE to the frontline surgeons.[

21] But based on the current research we concluded this has changed positively. As expected, we still noticed regional differences. The highest percentage of surgeons reporting adequate PPE came from Australia, although from this region only 4 responses were received, followed by Europe (second highest percentage) with 123 responses. On the other side of the spectrum of adequate PPE availability, we see that in Africa more than half of the surgeons still feel the hospitals do not provide adequate PPE. Instead of purchasing the PPE from foreign suppliers initiatives to produce PPE locally were embraced and initiated. As SC-2 is believed to become a recurrent seasonal disease and therefore such regional independence concerning PPE production and availability could be highly relevant for surgeons.[

24,

25]

The best protection is offered to the surgeons in Europe and North America with more than half of the surgeons indicate they can work with FFP3 and/or PAPR systems. On the other side of the spectrum there is Africa where the majority of CMF surgeons indicate that they have access to only surgical and/or FFP1 masks as the maximum protection. In addition, we also see in Asia, Europe, The Middle East, South America, and North America, there are still surgeons who must only rely on surgical masks. Although the surgical mask has also been shown to intercept other human coronaviruses the use of better masks is recommended as SC-2 is also embedded in aerosols <5 μm in diameter.[

26,

27] Overall, it is still alarming to hear surgeons around the globe are still not provided with optimal safe working environments, as the protective quality of a surgical mask may be insufficient for regular surgeons but are certainly insufficient for surgeons working with aerosolgenerating procedures.[

14,

26] The type of PPE used when caring for COVID-19 patients will vary according to the setting and the activity. For CMF surgeons, appropriate PPE should be worn for surgical procedures and ambulatory visits which includes N95/FFP2/FFP3 masks or PAPR systems.[

20]

Subsequently, to the WHO declaring the outbreak of SC2 as a global pandemic, in many countries, the recommendation to cancel elective operations appeared.[

1,

16,

20] This was 1 of the measures used to allow hospitals to surge their capacity of limited number of medical resources and serve the patient population with COVID-19 infections. In general, all elective surgical procedures were canceled and rescheduled after safe strategies were identified to limit occupational exposure. For surgeons working in the CMF field, the surgical procedures were limited to those involving emergent airway management, surgical management of facial fractures, infection, bleeding, and oncologic procedures in which a delay in management could affect ultimate outcome.[

20] In the beginning of the pandemic, CMF surgeons followed this advice and stopped elective surgery.[

21] From the results of this study, it shows that the vast majority of surgeons from all regions resumed performing elective surgery. As more PPE became available for surgeons over time, the test capacity increased, the peaks of infections and COVID-19 patient admissions in hospitals decreased, the elective procedures in OMFS practices resumed.[

28] It is suggested that the change of disease pattern and caseload will have a long-term impact on OMFS education, patient care, and training during and after the pandemic.[

28]

A favorable finding is that a vast majority of the surgeons has still not tested positive for SC-2. Although this number was even 10 times lower in the beginning of the pandemic. Because the number of surgeons who tested positive is still low and no information on source and contact of infection is available, it is hard to determine if SC-2 infection was community spread or due to the lack of adequate PPE availability. Vaccines against SC-2 have been developed relatively quickly and most countries have already started to vaccinate. Fortunately, the vast majority of the respondents are either partly or completely vaccinated. Neither a previous SC-19 infection, nor a vaccination against SC-2 guarantee a full protection for an infection, hence adequate PPE is still important.[

9,

10]

A limitation of this survey is the relatively low response rate which could potentially lead to a response bias. However, this is common in survey research and the response rate is comparable with the previous study conducted in the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.[

21] Since there is no information about the non-responders, we can only speculate on how this may have affected our findings. Another limitation of our study is that the number of responses from the region of Australia were low, therefore the results from this region should be interpreted cautiously. However, the previous survey also showed a similarly low number of respondents from this region and in our current study we excluded Australia from parts of the analysis.[

21] Another limitation of our study is that respondents with other specialties are also included, however, this was also the case in Van der Tas et al.[

21] Moreover, the crosssectional setting of the survey limits the ability to assess the effects of COVID-19 on the long term.

A great strength of this study is the large number of survey respondents. Because of this, a comparison between CMF surgeons from different geographical regions is possible. The number of survey respondents were similar to the number of respondents in the study conducted in the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.[

21] Furthermore, the original questionnaire was extensive, therefore the length of this survey was shortened. The percentage of missing data per analyzed variable was also relatively low. As another major strength of our study, we account the current research as the first investigation that provides scientific evidence of the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on CMF surgeons practice worldwide after 1 year. The findings of this study will be useful as a reference, not only for this specialty, but also for others, should COVID-19 or a similar global threat arise again in the future.

In conclusion, this survey outlines that the effects of COVID-19 on CMF surgeons globally concerning limited care to urgent or emergent cases and limited access to adequate PPE have partially improved since the beginning of the pandemic. Major findings from the survey are (1) the vast majority of CMF surgeons feel the hospitals do provide adequate PPE to them; (2) the vast majority of CMF surgeons restarted conducting elective surgery; and (3) lastly, the biggest part of CMF surgeons is either fully or partly vaccinated. As the COVID-19 pandemic is fast evolving therefore future surveys via the AO CMF network should capture what the long-term impact of the COVID-19 crisis on CMF surgeons and surgery will look like.