Recreational Motorized Vehicle Use Under the Influence of Alcohol or Drugs Significantly Increases Odds of Craniofacial Injury

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Variables

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

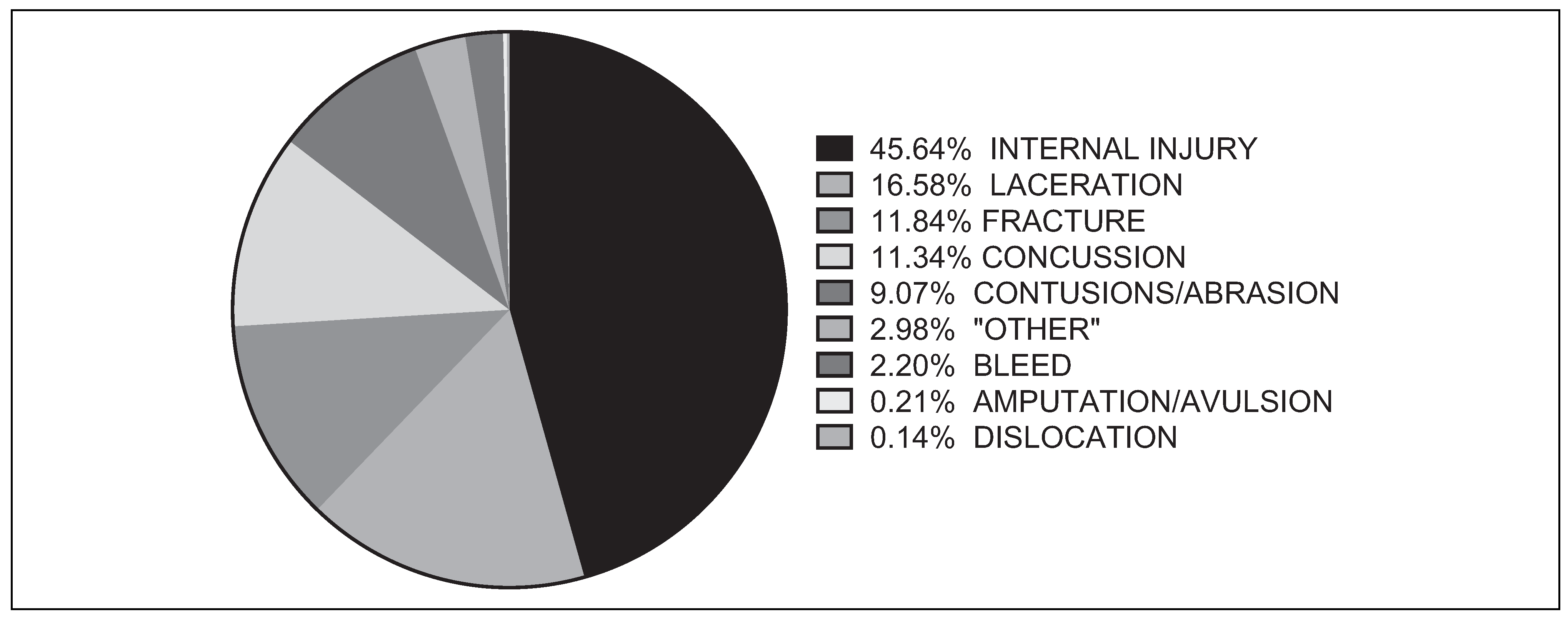

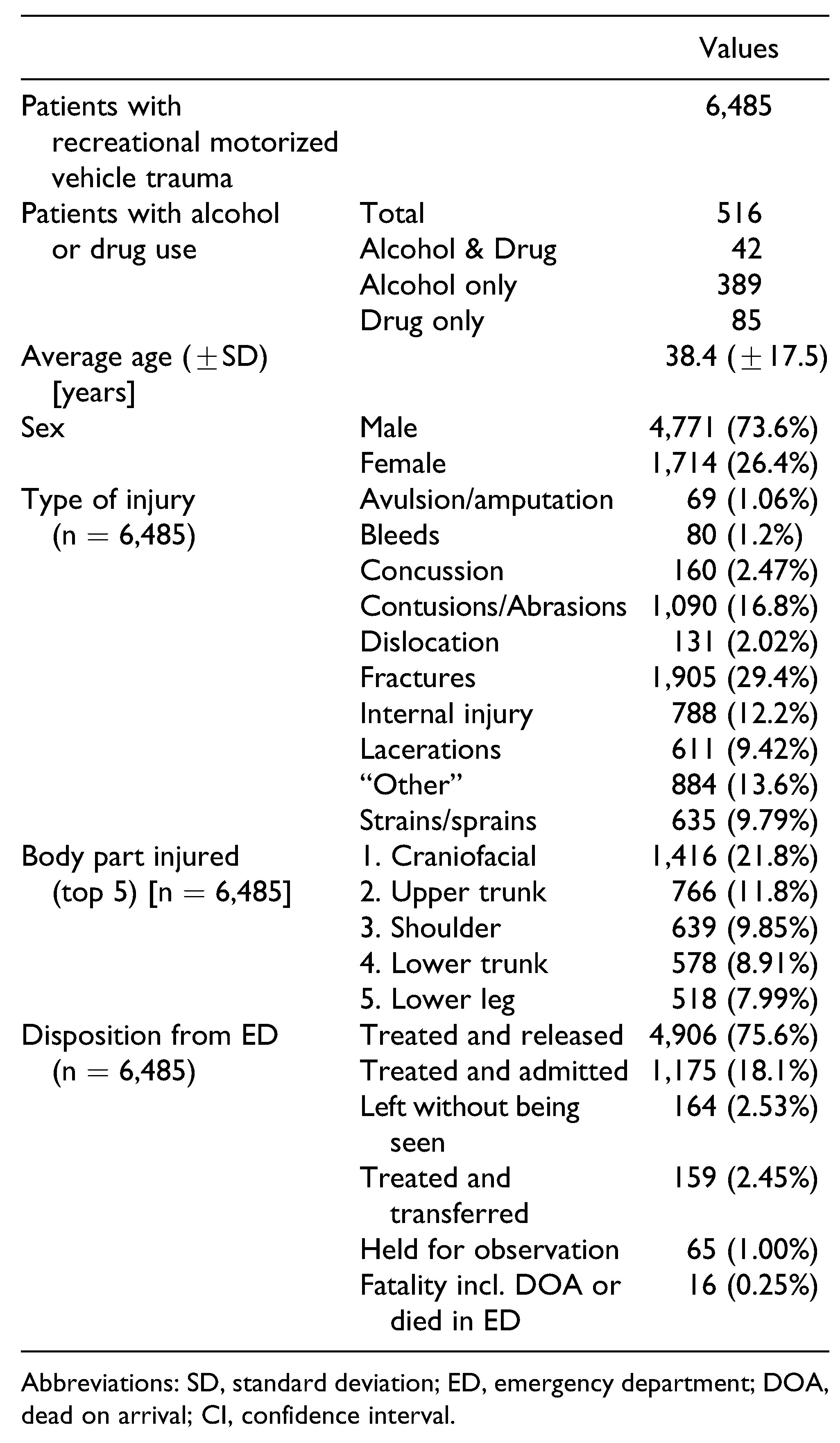

3.1. Overall Characteristics

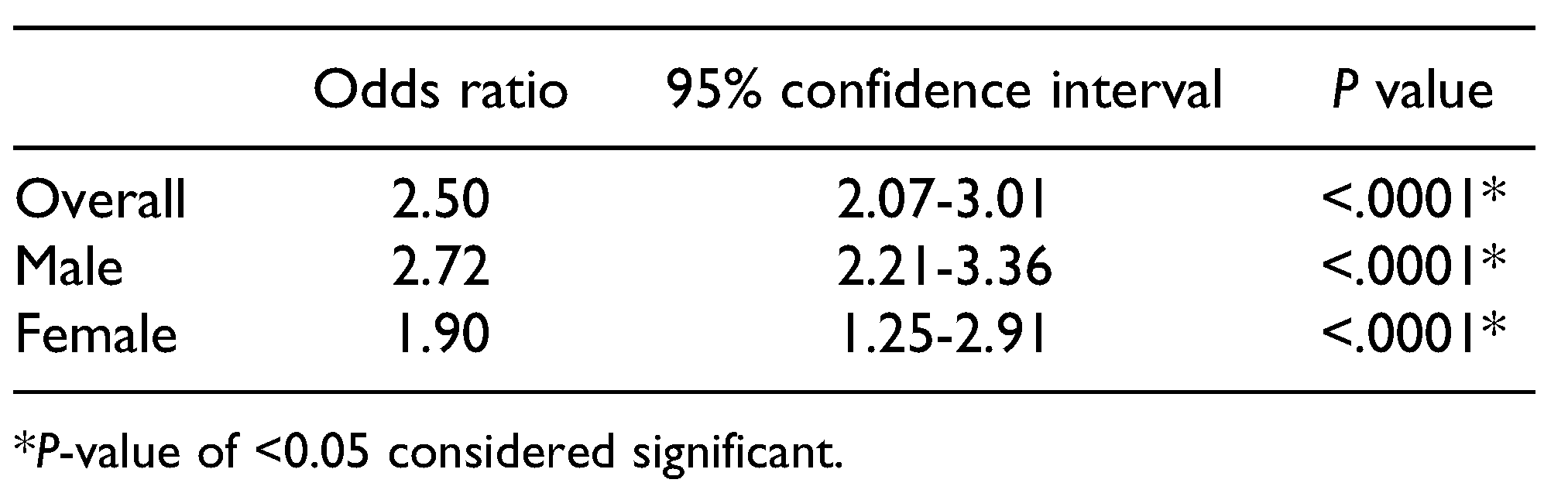

3.2. Alcohol or Drug Use and Craniofacial Injuries

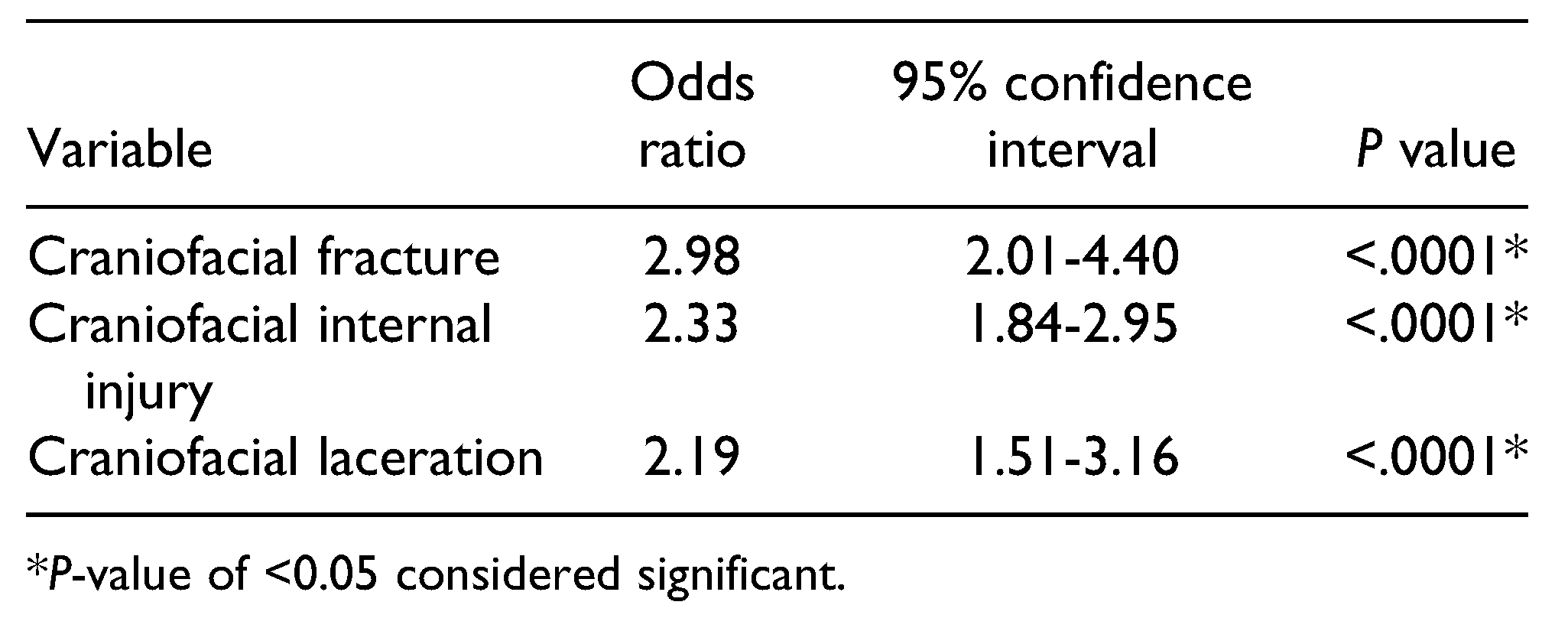

Alcohol or Drug Use and Craniofacial Fractures, Lacerations, and Internal Injuries

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusions

Funding

Statement of Informed Consent

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Topping, J. 2020 Report of Deaths and Injuries Involving Off-Highway Vehicles With More Than Two Wheels; US Consumer Product Safety Commission: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2020.

- Shaigany, K.; Abrol, A.; Svider, P.F.; et al. Recreational motor vehicle use and facial trauma. Laryngoscope. 2016, 126, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenkel, B.; Bahouth, H.; Abu Shqara, F.; Rachmiel, A. Craniofacial injuries seen among electric-motorized bicycle riders. J Craniofac Surg. 2020, 31, 2171–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission CPS. The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System: A Tool for Researchers; Consumer Product Safety Commission: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2000.

- Schroeder, T.; Ault, K. The NEISS Sample (Design and Implementation) 1997 to Present; US Consumer Product Safety Commission: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2001.

- Altman, D.G. Practical Statistics for Medical Research; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sheskin, D.J. Handbook of Parametric and Nonparametric Statistical Procedures, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- White, L.C.; McKinnon, B.J.; Hughes, C.A. Etiologies of pediatric craniofacial injuries: a comparison of injuries involving allterrain vehicles and golf carts. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 77, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, B.L.; Waller, J.L.; McKinnon, B.J. Craniofacial injuries due to golf cart trauma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011, 144, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, J.A.; Loder, R.T. All-terrain vehicle use related fracture rates, patterns, and associations from 2002 to 2015 in the USA. Injury. 2019, 50, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostas, J.W.; Donnellan, K.A.; Gonzalez, R.P.; et al. Helmet use is associated with a decrease in intracranial hemorrhage following all-terrain vehicle crashes. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014, 76, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Airaksinen, N.K.; Nurmi-Lüthje, I.S.; Kataja, J.M.; Kröger, H.P.J.; Lüthje, P.M.J. Cycling injuries and alcohol. Injury. 2018, 49, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagemeister, C.; Kronmaier, M. Alcohol consumption and cycling in contrast to driving. Accid Anal Prev. 2017, 105, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleiner, J.E.; Johnson, J.; Cruz, A.I. Trends in all-terrain vehicle injuries from 2000 to 2015 and the effect of targeted public safety campaigns. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018, 26, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touma, B.J.; Ramadan, H.H.; Bringman, J.J.; Rodman, S. Maxillofacial injuries caused by all-terrain vehicle accidents. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999, 121, 736–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, M.I.; Shuman, A.G.; Montero, P.H.; Palmer, F.L.; Shah, J.P.; Patel, S.G. Accuracy of administrative and clinical registry data in reporting postoperative complications after surgery for oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2015, 37, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carniol, E.T.; Shaigany, K.; Svider, P.F.; et al. Beaned: a 5-year analysis of baseball-related injuries of the face. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015, 153, 957–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilbronn, C.M.; Svider, P.F.; Folbe, A.J.; et al. Burns in the head and neck: a national representative analysis of emergency department visits. Laryngoscope. 2015, 125, 1573–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, L.A.; Svider, P.F.; Raza, S.N.; Zuliani, G.; Carron, M.A.; Folbe, A.J. Hockey-related facial injuries: a population-based analysis. Laryngoscope. 2015, 125, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagga, H.S.; Fisher, P.B.; Tasian, G.E.; et al. Sports-related genitourinary injuries presenting to United States emergency departments. Urology. 2015, 85, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.J.; Chan, J.J.; Linakis, J.G.; Mello, M.J.; Greenberg, P.B. Age and consumer product-related eye injuries in the United States. R I Med J (2013). 2014, 97, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sorenson, T.J.; Borad, V.; Schubert, W. A nationwide study of skiing and snowboarding-related facial trauma. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, D.R.; John, D.; Conger, S.A.; Fitzhugh, E.C.; Coe, D.P. Trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviors of United States youth. J Phys Act Health. 2015, 12, 1102–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Alcohol/drug use (n = 201) | No alcohol/drug use (n = 1,215) | P-value | ||

| Average age (+SD) [years] | 37.2 (+13.3) | 38.7 (+19.2) | .2866 | |

| Sex | Males | 165 (82.1%) | 847 (69.7%) | .0003* |

| Most common types of injury | Bleeds | 3 (1.5%) | 28 (2.3%) | .4727 |

| Contusions/abrasions | 13 (6.5%) | 115 (9.5%) | .1703 | |

| Fractures | 33 (16.4%) | 134 (11.0%) | .0278* | |

| Internal injury | 98 (48.8%) | 546 (44.9%) | .3038 | |

| Lacerations | 36 (17.9%) | 198 (16.3%) | .5717 | |

| Disposition from ED | Treated and released | 123 (61.2%) | 885 (72.8%) | .0008* |

| Treated and admitted | 58 (28.9%) | 248 (20.4%) | .0067* | |

| Left without being seen | 8 (4.0%) | 28 (2.3%) | .1562 | |

| Treated and transferred | 9 (4.5%) | 34 (2.8%) | .1937 | |

| Held for observation | 3 (1.5%) | 16 (1.3%) | .8186 | |

| Fatality incl. DOA or died in ED | 0 (0%) | 4 (0.3%) | .4370 | |

© 2021 by the author. The Author(s) 2021.

Share and Cite

Sorenson, T.J.; Rich, M.D.; Lamba, A.; Deitermann, A.; Barta, R.J.; Schubert, W. Recreational Motorized Vehicle Use Under the Influence of Alcohol or Drugs Significantly Increases Odds of Craniofacial Injury. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2022, 15, 282-287. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211046721

Sorenson TJ, Rich MD, Lamba A, Deitermann A, Barta RJ, Schubert W. Recreational Motorized Vehicle Use Under the Influence of Alcohol or Drugs Significantly Increases Odds of Craniofacial Injury. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2022; 15(4):282-287. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211046721

Chicago/Turabian StyleSorenson, Thomas J., Matthew D. Rich, Abhinav Lamba, Annika Deitermann, Ruth J. Barta, and Warren Schubert. 2022. "Recreational Motorized Vehicle Use Under the Influence of Alcohol or Drugs Significantly Increases Odds of Craniofacial Injury" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 15, no. 4: 282-287. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211046721

APA StyleSorenson, T. J., Rich, M. D., Lamba, A., Deitermann, A., Barta, R. J., & Schubert, W. (2022). Recreational Motorized Vehicle Use Under the Influence of Alcohol or Drugs Significantly Increases Odds of Craniofacial Injury. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 15(4), 282-287. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211046721