Introduction

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) in late December 2019 has spread globally causing a pandemic of respiratory illness.[

1] The first reported case of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019n-CoV) in the United States was on January 20, 2020 in Washington State. The patient was a 35-year-old male who just returned from visiting family in Wuhan, China.[

2] On January 30, 2020, The World Health Organization (WHO) announced a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) noting 7711 confirmed and 12167 suspected cases with 170 deaths in China along with 83 cases in 18 other countries. Only 7 cases reported no travel history to China.[

3] Later the WHO announced “COVID-19” as the official name of this new disease on 11 February 2020.[

4] The first confirmed case in the State of Tennessee occurred on March 5, 2020 in an adult male who recently traveled out-of-state and lives in a southern suburb of Nashville.[

5] On March 11, 2020 the WHO declared COVID-19 a global pandemic.[

6]

Subsequently as cases increased, many local governments issued varying degrees of stay-at-home or lockdown-type orders. Nashville Mayor John Cooper issued a “Safer-at Home Order” starting Monday March 23, 2020 which closed all non-essential businesses and encouraged residents to stay at home whenever possible.[

7] Healthcare services were basically limited to essential and emergency care. This order was extended 4 times over the following 7 weeks as Nashville entered phases of reopening.[

8] The purpose of this study is to understand the impact of the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic on the epidemiology of maxillofacial trauma at an urban trauma center. The author hypothesized that the number of maxillofacial injuries would decrease during the initial phase of the pandemic resulting from stay-at-home orders and then rebound during the reopening phase. The specific aims were to (1) measure and compare the frequency of maxillofacial injuries during the period of the pandemic versus the year prior; (2) estimate and compare the etiology of maxillofacial injuries between the 2 groups; (3) estimate and compare the frequency and etiology of maxillofacial injuries between the initial phase of the pandemic compared to the reopening phase.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

To address the research purpose, the investigator designed and implemented a retrospective cohort study. The study sample was derived from the population of patients who presented to TriStar Skyline Medical Center, in Nashville, Tennessee for evaluation and management of maxillofacial injuries during 2 time periods; (1) beginning March 1, 2020 and ending August 31, 2020; (2) beginning March 1, 2019 and ending August 31, 2019. To be included in the study sample, patients must (1) have been managed during the above mentioned time periods; (2) have had records adequate for data abstraction; (3) have data that is recorded in the Facial Trauma Database at TriStar Skyline Medical Center. Patients were excluded from the study if they (1) had inadequate medical records preventing data abstraction; (2) if they were not entered into the Facial Trauma Database. This study was reviewed and received Institutional Review Board Approval (HCA 2020-990).

Study Variables

The primary predictor variable was the period which the subject presented for evaluation of their maxillofacial injury. The experimental group included those who presented during the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, beginning March 1, 2020, and ending August 31, 2020. The control group included those who presented the year prior, beginning March 1, 2019 and ending August 31, 2019. The initial phase of the pandemic was defined from March 1 through May 31, 2020. The reopening phase was defined from June 1 through August 31, 2020. The primary outcome variable was injury volume. Demographic, etiologic, and anatomic variables were recorded for all patients. Demographic variables included age, gender, and initial presentation (inpatient or outpatient). Etiologic variables were classified according to 4 major causes: assault, falls, vehicular injuries, and sport or other blunt mechanisms. Anatomical variables were recorded as upper face, middle face, lower face, or multiple locations.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection was performed, and all data was deidentified and kept in a secure spreadsheet accessible only by the principle investigator. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all study variables in each cohort. Bivariate data analysis was performed to evaluate the association between the predictor and outcome variables with significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Descriptive and analytic statistics are presented in

Table 1. The final study sample was composed of 415 subjects with maxillofacial injuries that presented to TriStar Skyline Medical Center. The number of subjects in the 2020 cohort (n = 212) was 4.2% higher than the 2019 cohort (n = 203). Most of the subjects were male (72% in 2020, and 67% in 2019,

P = .27). The average age of the subjects was 45.9 (15-99) in 2020, compared to 42.7 (14-94) in 2019 (

P = .09). The percentage of inpatient subjects were similar in the 2 groups (77% in 2020, and 78% in 2019,

P = .81). The most common etiology of injury for the 2020 cohort was related to falls (31%), whereas assault (35%,

P = .34) was the most common for the 2019 cohort. The anatomic region of injury was constant in both cohorts with midfacial injuries being the most prevalent (61% in 2020, and 55% in 2019,

P = .59) followed by lower facial injuries (28% in 2020, and 33% in 2019,

P = .59).

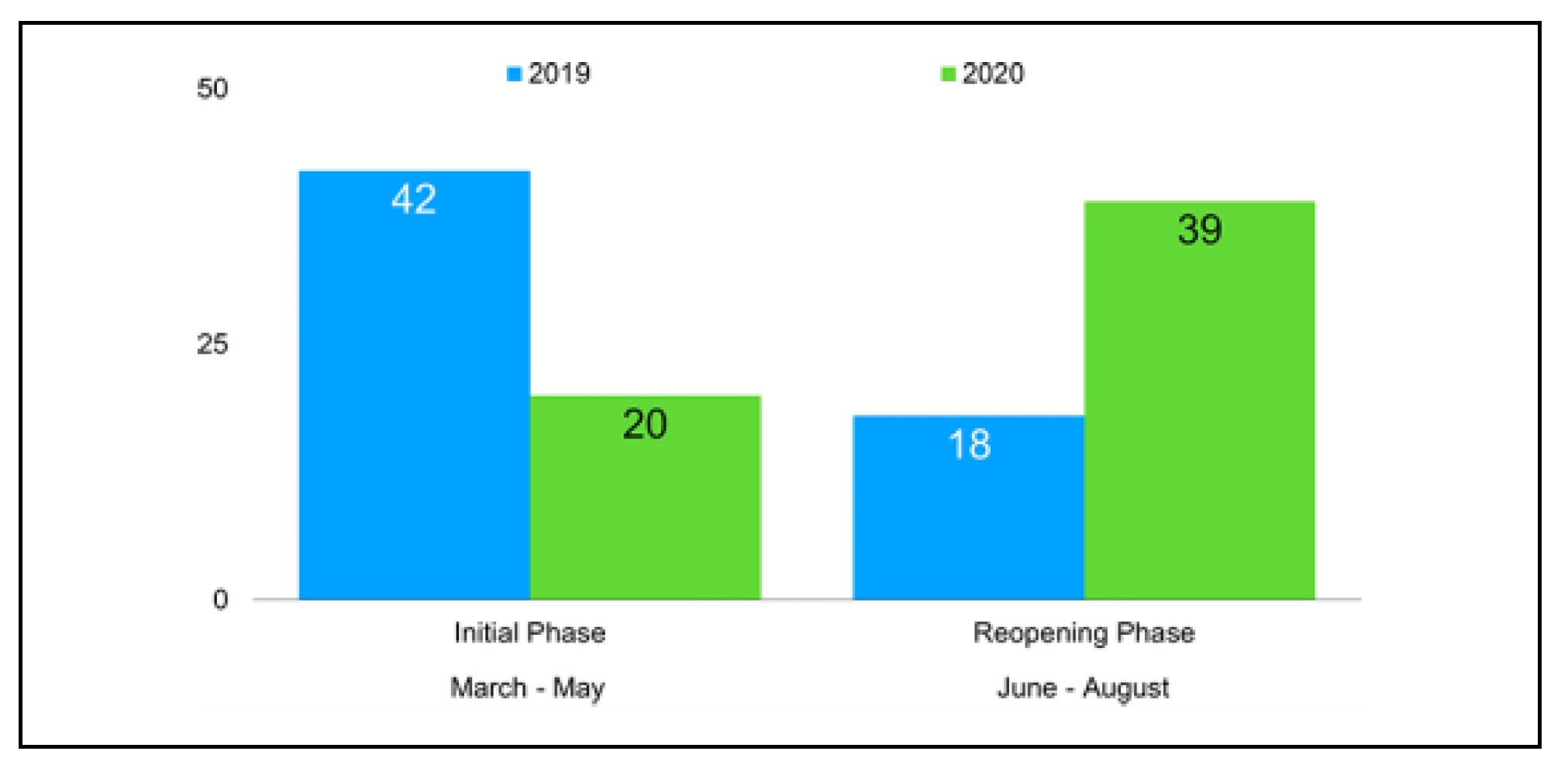

Figure 1 shows a bar chart differentiating the monthly trauma volume.

Table 2 presents bivariate analysis of the monthly volume between the predictor variable and the outcome variables. The monthly volume started to show a significant decrease in April (n = 25 in 2020 versus n = 43 in 2019,

P = .04) with reversal of the trend starting in June (n = 48 in 2020 versus n = 32 in 2019,

P = .04). A similar trend was noted for subjects seen as outpatients (

P < .001) and for injuries caused by interpersonal violence (

P = .001). Other etiologic variables such as falls (

P = .19), vehicular injuries (

P = .66) and sport or other blunt mechanisms (

P = .63) did not show a significant change based upon monthly volume.

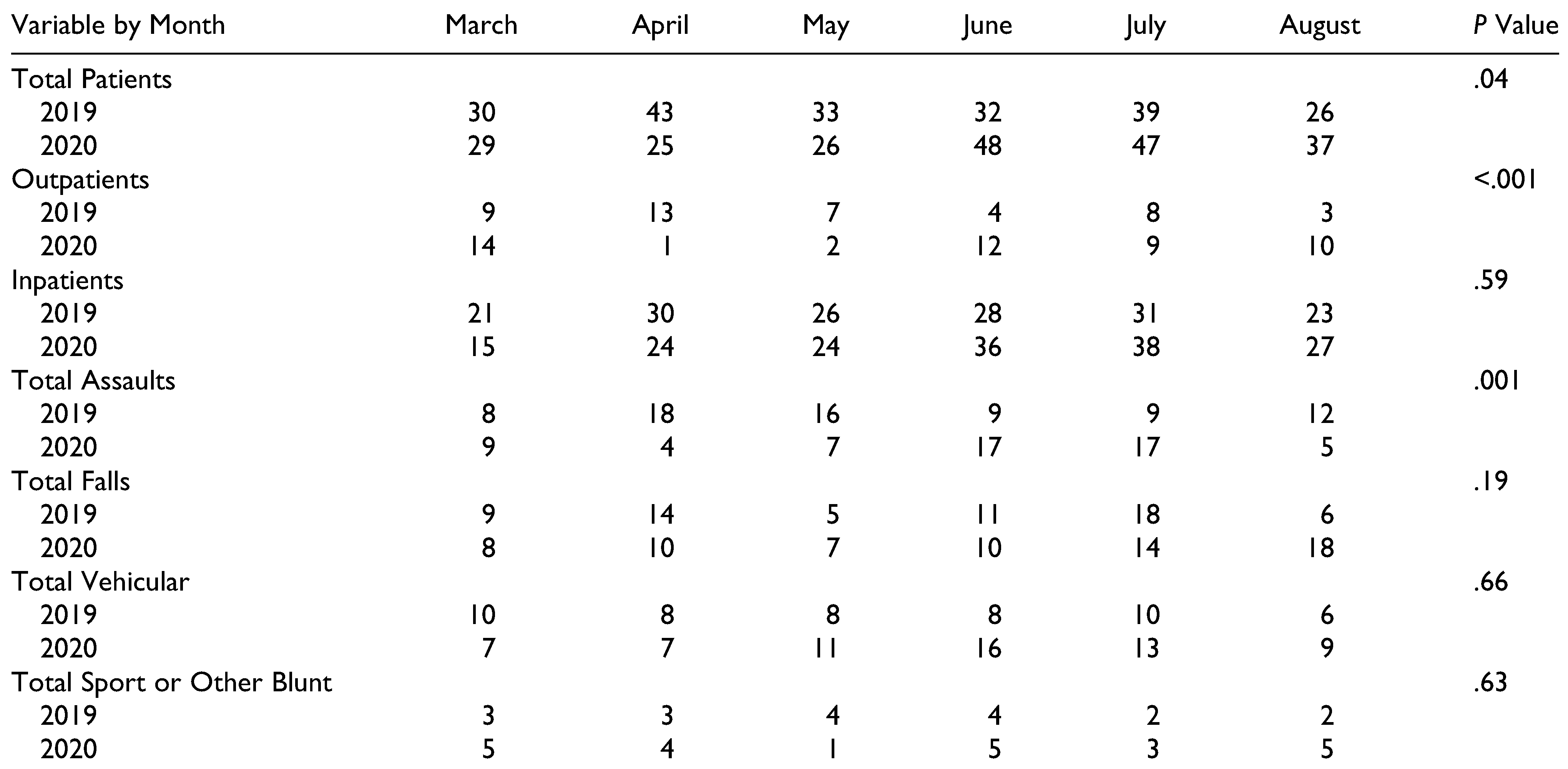

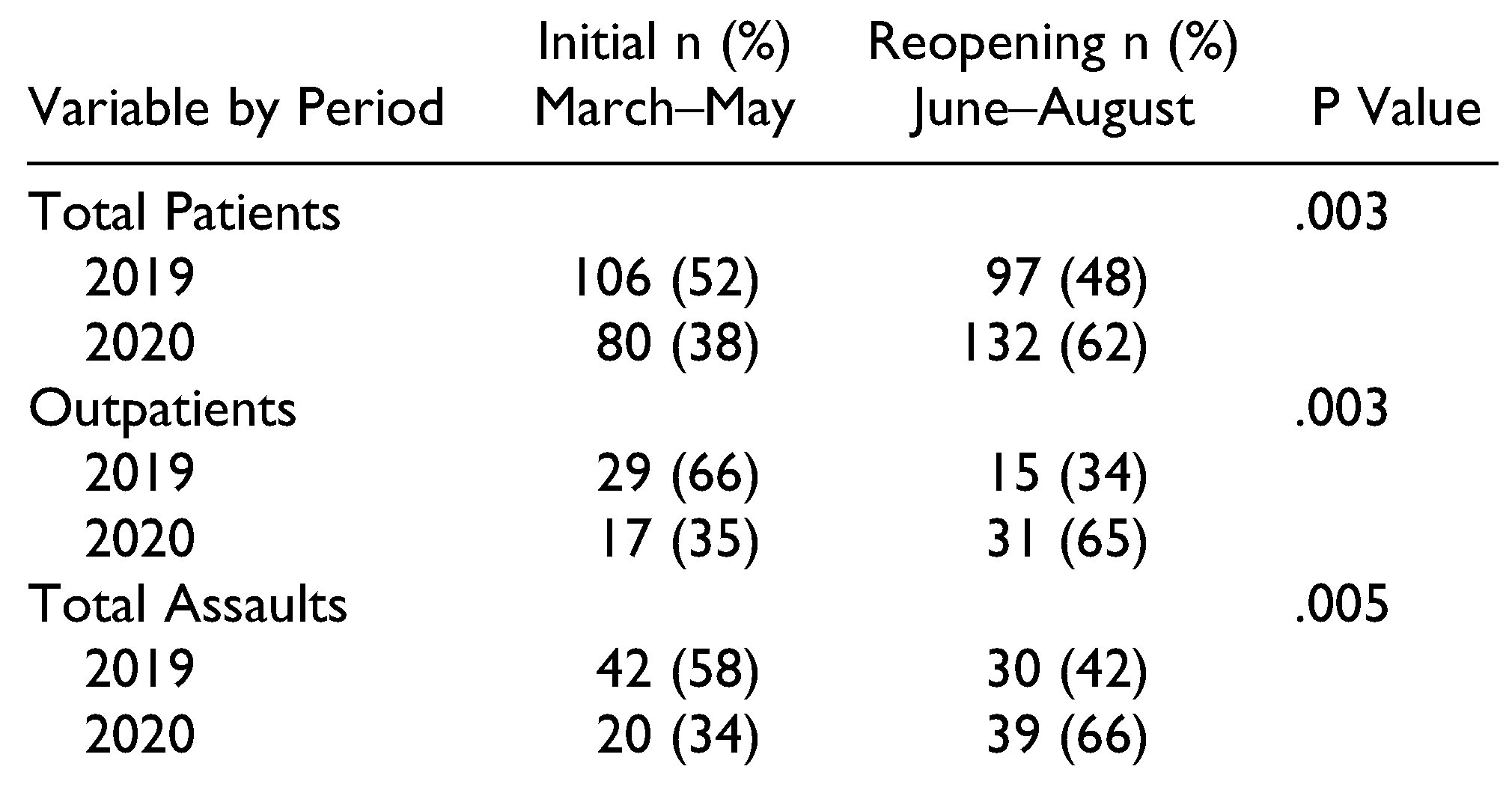

Table 3 presents descriptive and bivariate analysis of the significant findings from

Table 2 grouped into the 2 different phases (Initial: March–May 2020 and Reopening: June–August 2020) of the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the same periods in 2019. Subject volume decreased 24.5% during the first initial phase of the pandemic with a 36.1% increase in volume occurring during the reopening phase (

P = .003). Outpatient volume decreased by 41.4% during the initial phase and increased 106.7% during reopening phase (

P = .003). Volume related to interpersonal violence is represented in

Figure 2 resulting in a 52.4% decrease during the initial phase of the pandemic with a rebound increase of 30% during reopening (

P = .005).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to understand the impact of the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic on the epidemiology of maxillofacial trauma at an urban trauma center in Nashville, Tennessee. The author hypothesized that the number of maxillofacial injuries would decrease during the initial phase of the pandemic resulting from stay-athome orders and then rebound during the reopening phase. The specific aim was to quantify and analyze the frequency of maxillofacial injuries sustained by individuals who presented during the initial phase of the pandemic and subsequent reopening.

The results of this study confirm the hypothesis that an initial decrease in maxillofacial trauma occurred during the initial phases of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, followed by a rebound in volume during the phases of reopening. Nashville, Tennessee first reported cases of COVID-19 in early March 2020. This led to a period of regional lockdown and very limited reopening that extended until the end of May. At that point there were 5517 reported COVID-19 cases with 63 deaths.[

9] Phase II was then initiated that allowed the limited reopening of restaurants, bars, and commercial businesses at 3/4 capacity with appropriate social distancing.[

10]

Following the start of the 2020 COVID-19 initial period, a 41.8% decrease in volume occurred in April and a decrease of 21.2% occurred in May. An overall decrease in crime was noted during the beginning of the pandemic, with a 17% decrease in burglary and 5% decrease in violent crimes according to a report by the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation.[

11] The corresponding volume of injuries from interpersonal violence showed a similar, but more dramatic pattern with a 77.8% decrease in April and a 56.3% reduction in May compared to 2019. This decrease was directly related to the stay-at-home orders, practicing social distancing when out and limited access to restaurants and bars.

Hospital emergency departments reported an overall 42% reduction in volume during the early phases of the pandemic.[

12] An 85% decreased in outpatient referrals occurred during April and May compared to the year prior. The initial phases of the pandemic demonstrated widespread uncertainty and public anxiety. Many patients with acute illness, whether life threatening or not, did not seek care out of fear of contagion or concerns about access at COVID-19 overrun hospitals.[

13]

As Nashville emerged out of lockdown, and into Phase II reopening, a rebound in maxillofacial trauma evolved. In June 2020, a 50% increase in total volume occurred. Injuries from vehicular accidents increased 100% and patients presenting with injuries from assault outpaced the overall trauma gains by increasing 88.9% compared to 2019. This is consistent with other reported trends. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration reported that crash-related deaths increased in April and extended into the second half of 2020 as drivers were exhibiting riskier behavior even though there were less drivers on the road.[

14]

Through the end of August 2020 crime had rebounded in Nashville as well, the number of assaults increased by 18% and homicides increased by 38% year to date.[

15] The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly changed the daily lives of individuals. Abusive situations can further escalate due to social and economic crisis brought on by quarantine. Stringent measures, that many communities initiated to contain and manage the epidemiologic emergency has increased stress on the structure of families with a potential deleterious effect on mental and physical health.[

16]

The main limitation of this study was that it was a retrospective, single-institution study. The time frame chosen of a 3-month initial period, followed by a 3-month period of reopening may not be representative of a national profile. However, this is the first study to evaluate the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic as it relates to maxillofacial trauma. The use of the same period 1 year prior to develop the control cohort, eliminated seasonal variability that can occur in trauma. It is reasonable to assume that patients with very minor injuries may have not sought evaluation and treatment due to the fears of the pandemic initially. However, as reopening progressed and became the new normal, more people sought care as outpatients then requesting transfer to avoid the overburdened hospitals and the perceived potential risk of being admitted with possible exposure to the contagion. At the end of this study on August 31, 2020 there were 26,019 reported COVID-19 cases with 239 deaths in Nashville, Tennessee. [

17]