1. Introduction

Following the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, Health Systems of many countries around the world had to urgently reorganize all the activities. [

1]

The infection originated in China (Wuhan, region of Hubei) [

2] and Italy was the first nation in the Western Countries to show this emergency. Considering the territorial characteristics and population density (total population =10,060,574, inhabitants/km

2 = 422), [

3] the number of infected and the number of deaths, at the beginnings of March Lombardy was worldwide the most affected region by COVID-19 disease. [

4]

This condition produced an enormous stress for the Lombard health system, requiring a long lockdown period for the population and a rapid reorganization of the management of conventional time-dependent diseases.

The identification of “Hub-function” Centers for the main urgent/emergent diseases has become necessary to allocate the remaining resources to the care of COVID-19 patients. Niguarda Hospital in Milan was selected as main Regional Trauma Center.

All others Hospitals, including Maxillofacial Surgery Departments, were involved in an immediate change in planning and working methods, with suspension of scheduled activities and reference to these Hub Centers for non COVID-19 related pathologies. [

5]

The prolonged lockdown period (beginning March 10, end May 4, 2020), on the other hand, has substantially changed the habits of citizens with a possible epidemiological effect on emergencies.

The purpose of this work is to report the experience of Niguarda Hospital Maxillofacial Surgery Team during the lockdown period, by verifying the epidemiological changes in the presentation of trauma and by comparing them with the same period of the previous 3 years.

2. Materials and Methods

In this paper we analyze the activity of Niguarda Trauma Center in Milan, for the period between March 8, 2020 and May 8, 2020 (corresponding to its Hub function for Major Trauma) and compare it with its activity during the same period in 2017–2019 years.

Characteristics of patients managed by Trauma Team and admitted during the established range of days, have been recorded on a specific database: gender, age, date of injury and presence of facial fractures.

Mechanisms of injury have also been recorded following classification of Utstein tamplate: “intentional” mechanisms have been categorized into violence or attempted suicide, “unintentional” into road accident (with or without motor vehicle involvement), domestic and free time/work accidents. [

6]

The same characteristics have been recorded for patients managed by Maxillofacial Team for isolated facial trauma, without Major Trauma features.

Inclusion criteria were admission with diagnosis of Major Trauma (defined as trauma with potential or ongoing life-threatening injuries) or facial trauma with at least 1 fractured facial bone. For each patient with facial trauma the fracture type and location, severity of facial injuries (measured according to the CFI score [

7,

8]) and indications for surgical treatment or non-operative management (NOM) were also noted.

Patients with soft tissue contusion, abrasion or simple laceration (treated under local anesthesia or in outpatients basis by the emergency department general Staff), patients with uncompleted or greenstick fractures or without complete clinical and radiological documentation, were excluded.

The whole sample is 216 patients, 151 (70%) male and 65 (30%) female; mean age was 42.5 (+20.9) years. One hundred and eighty-one were patients with diagnosis of Major Trauma, 36 of which had also facial fractures; 35 patients had isolated facial fractures. All of patients were admitted for trauma and none of them went to the hospital for other health reasons.

All patients with the indication for hospitalization underwent a nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 genome research, at the time of the first evaluation. Each stable or responder patient with major trauma also performed a torso CT-scan as part of the Primary Survey. The doubtful cases have been extensively studied with examination of the tracheo-bronchial aspirate. Positivity to one or more of these tests has been recorded into the data base; positive patients were admitted to “Trauma Covid” Hospital Ward, negative ones to Trauma Team or Maxillo Facial Wards.

This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki on medical protocol and ethics. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, it was granted an exemption in writing by the local ethical commitee.

Statistical Analysis

Absolute and percentage frequencies were used to describe categorical items while mean values and standard deviation were used for continuous characteristics. Fisher’s exact test and sum rank test were used to analyze differences between groups stratified according to year and Mechanism of injury. p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Cumulative incidence was plotted and linear model and regression analysis was applied to compare the 2020 COVID-19 period to the corresponding period of 3 previous years; Regression coefficients were used to measure and compare the incidence trends. Years in which qualitative analysis shows a bimodal behavior of cumulative incidence, where better described using 2 specific Regression coefficient for each period. Stata software 9.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas) was used for performing statistical analysis.

3. Results

Samples size and characteristics of major trauma admitted to the Trauma Center, for each year from 2017 to 2020, are summarized in

Table 1.

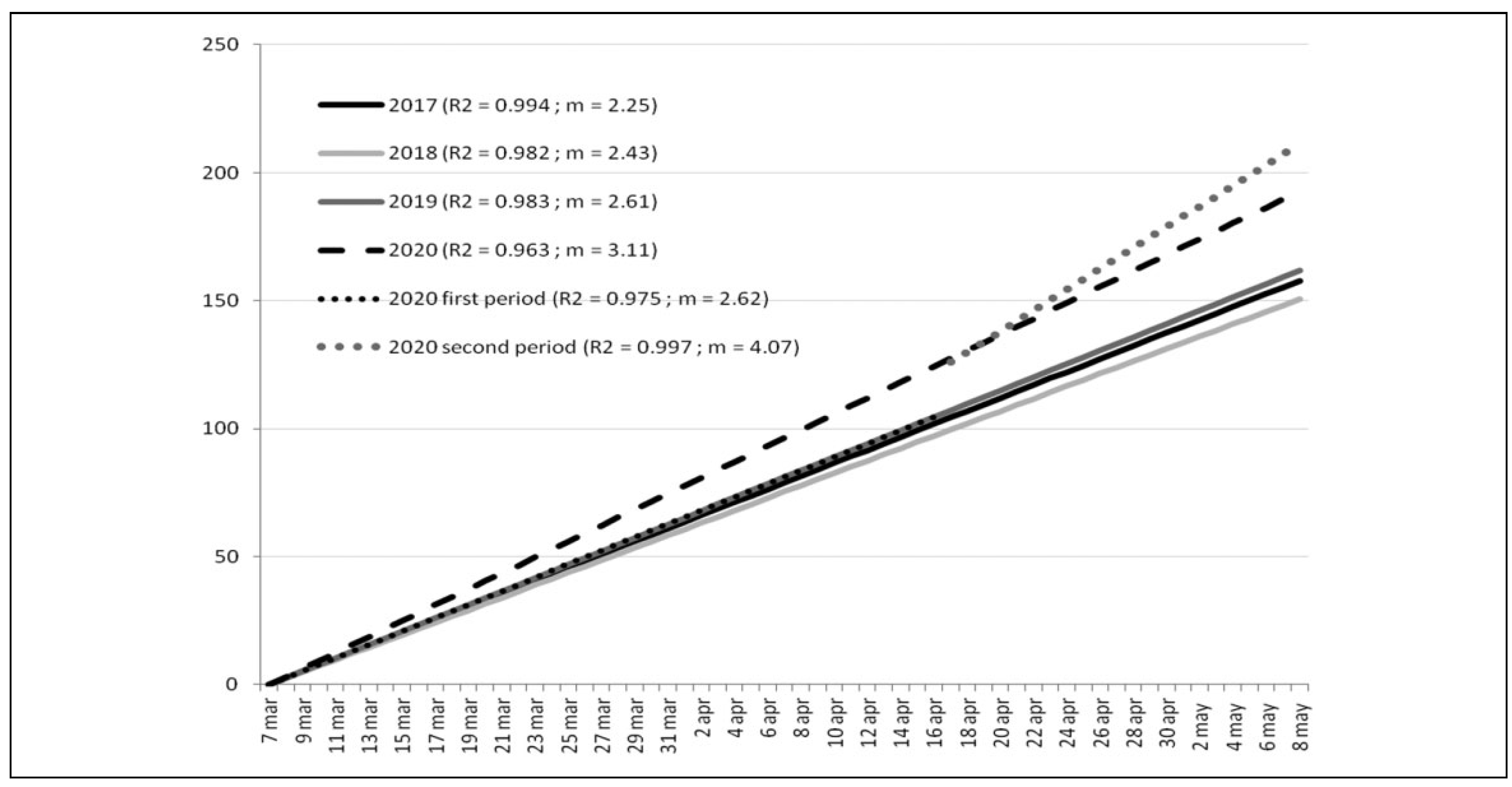

Linear regressions corresponding to the annual (from 2017 to 2020) cumulative incidence of patients admitted because of Major Trauma, are represented in

Figure 1. The angular coefficient showed substantial stability in the years 2017–2019 (m = 2.25 in 2017, m = 2.43 in 2018 and m = 2.61 in 2019). In 2020, the overall angular coefficient increased slightly (m = 3.11), but the linear regression for this year shows a 2-step trend that can best be described using 2 distinct coefficients: one for the period March 8 to April 16, which can be superimposed on that of previous years (m = 2.62), and the other for the period April 16 to May 8, a true expression of the increase observed for the year 2020 (m = 4.07). For all of these results, the coefficient of determination proved to be extremely satisfactory, with a minimum value of R2 = 0.963 (

Figure 1).

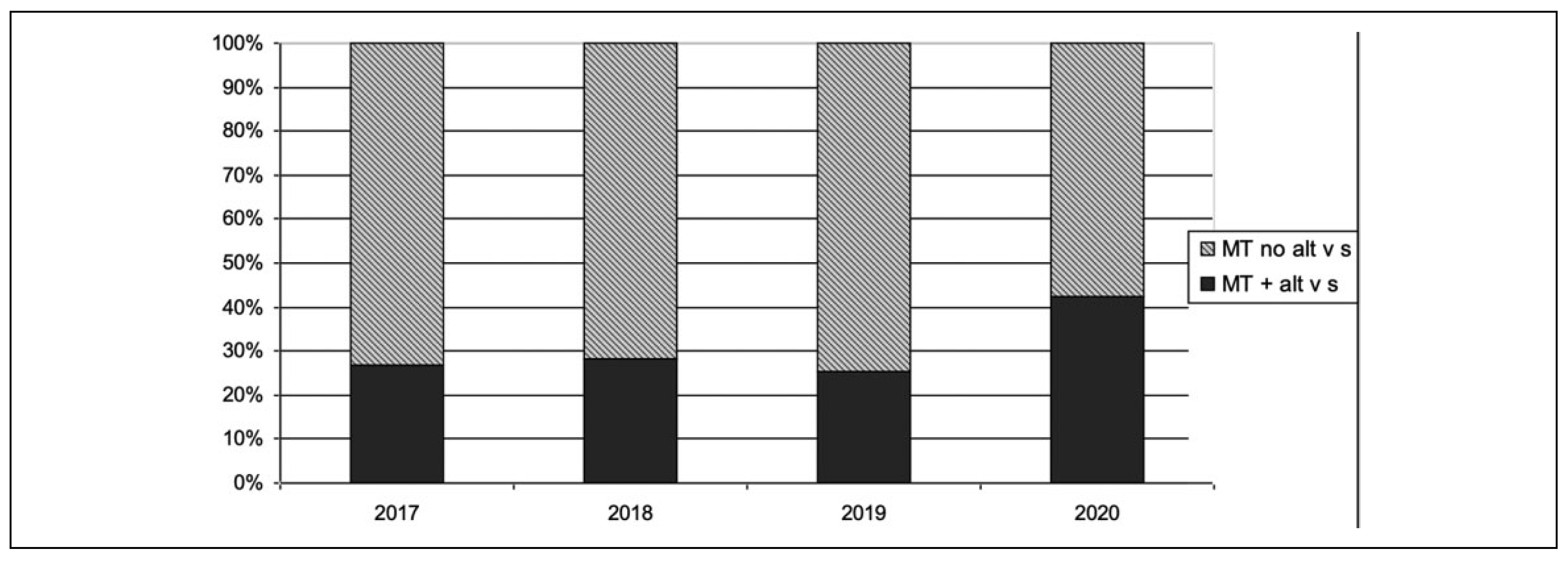

The proportion between patients with diagnosis of Major Trauma and more complex patients, with major trauma and alteration of at least 1 vital sign, was calculated for each year. The most challenging patients were 27% in 2017, 28% in 2018 and 26% in 2019, while in 2020 the proportion increased to 43% (

Figure 2).

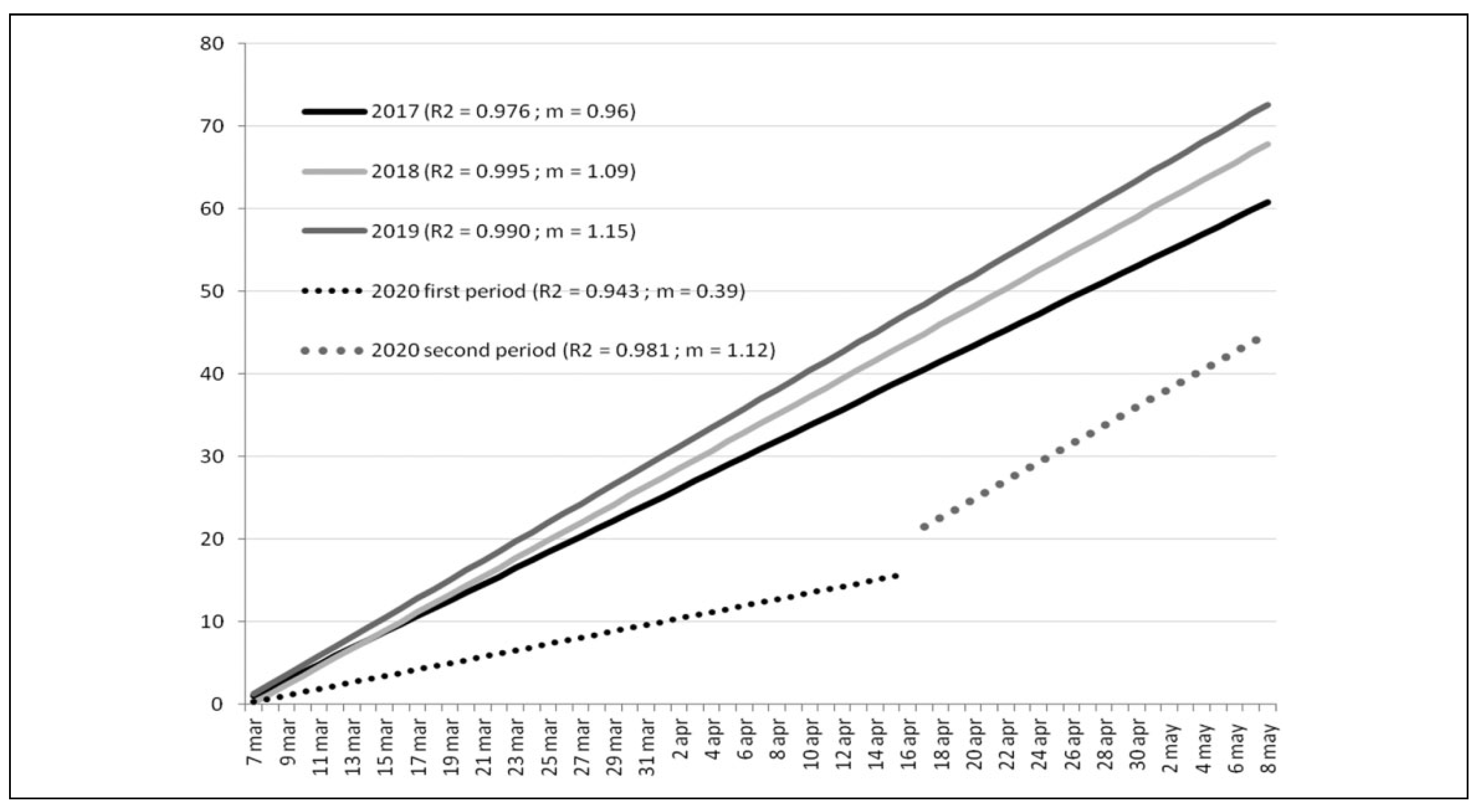

As in

Figure 1,

Figure 3 display year-specific linear regression representing cumulative number of patients, admitted exclusively because of Motor vehicle accidents. The angular coefficient was m = 0.96 in 2017, m = 1.09 in 2018 and m = 1.15 in 2019. Once again the 2020 regression shows a 2-step behavior, described with 2 distinct coefficient: m = 0.39 for the period March 8 to April 16 and m = 1.12 for the period April 16 to May 8. The minimum coefficient of determination was R2 = 0.943 (

Figure 3).

Table 2 shows the mean + SD age of major trauma patients per year, divided according to 3 main Mechanisms of injury: road accidents (with or without motor vehicles involvement), intentional (violence and attempted suicide) and daily activities (work, free time and domestics).

Characteristics of the 2020 sample divided into Major Trauma, with and without facial involvement, and patients with isolated facial trauma (without Major Trauma features) are resumed in

Table 3.

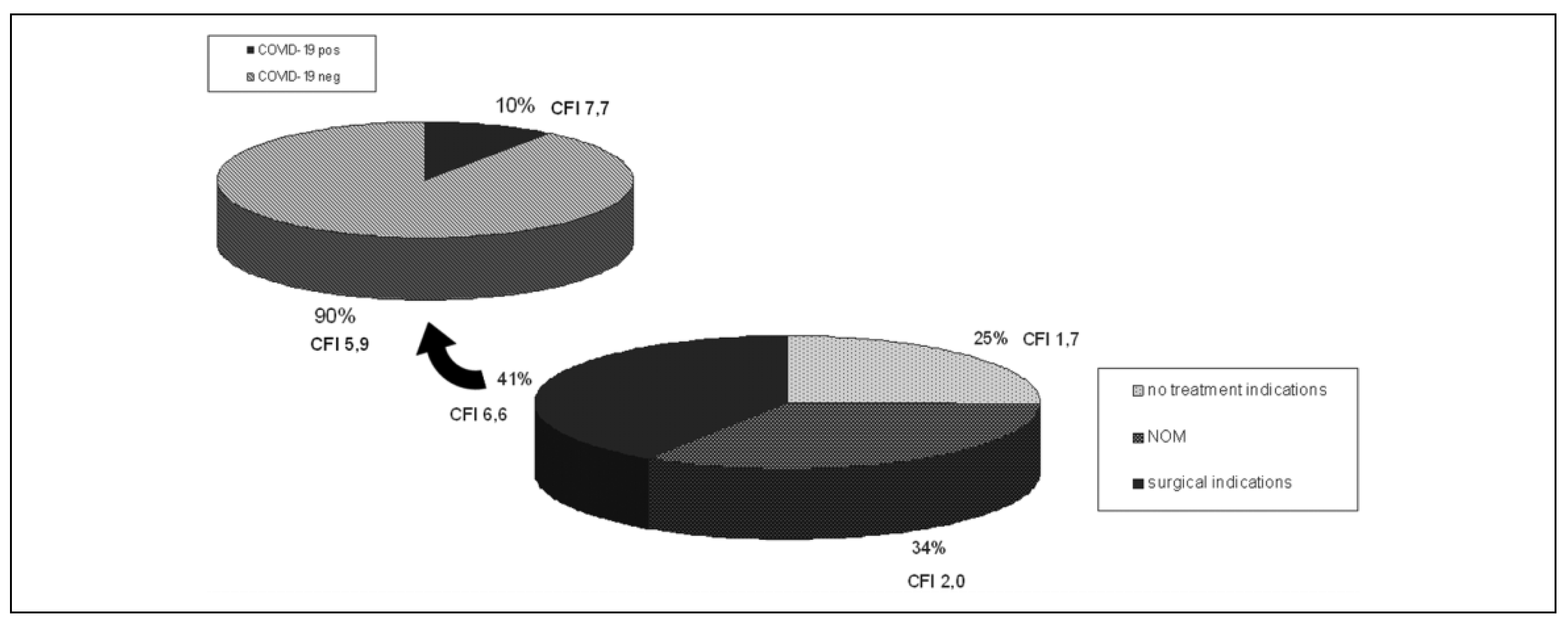

71 patients present facial trauma; 29 (41%) of which had an indication to surgery, 24 (34%) underwent NOM and 18 (25%) had indication to any treatment (

Figure 4). The prevalence of patients with diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection, within the surgically treated sample, was 10% (3 patients).

Figure 4 points out these results and also the mean CFI score assigned for each group.

4. Discussion

The identification of Niguarda Hospital as a Hub for Major Trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic by the Regional Government, as well as the complete suspension of any planned surgical activity, meant that the resources available for severe injured patients increased compared to previous years.

The total number of patients admitted with diagnosis of Major Trauma during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Milan substantially confirms the load of admission observed for the previous 3 years (

Table 1).

The cumulative number of patients’ curve, for each year, has been equated to a linear regression line with a specific angular coefficient (

Figure 1), that showed a superimposable trend for the years 2017–2019. This means that an average of 2.5 patients/day have been admitted for each of these years. The angular coefficient during the lockdown period 2020 shows a moderate increase (3.1 patients/day) and describes the maintenance of the activity of the Hub Center against an overall decrease of major trauma cases in Lombardy (

Figure 1).

The cumulative increase curve for the year 2020, however, shows a less linear trend than those of the previous years, with an evident slope increase starting from the middle of April. This trend is better described using 2 distinct linear regression lines: one for the first period (March 8 to April 16) and the other for the second period (April 16 to May 8). It is thus observed that the angular coefficient for the first period overlaps that of previous years (2.6 patients/day) while the overall increase is related to the second period coefficient (4.0 patients/day) (

Figure 1).

From a political point of view this coincides with the start of a selective reopening of the activities, compared to the first period absolute lockdown, decided by the Italian government in the middle of April. So the first month shows an increase in the total number of patients with consensual trend compared to previous years, then the curve changes its slope to a more vertical one, crossing previous years and ceiling at the end of the lockdown with an increase of 30% of the total cases (

Figure 1).

Cases in 2020 are also characterized by an overall increase in injury severity, with a greater proportion of patients admitted with alteration of at least 1 vital sign (

Figure 2,

p < 0.002).

By dividing the major trauma sample of 2020 by the Mechanism of injury, we can also observe an overall reduction in total road accidents compared to the average of previous years (24.3% against 44.1% of the total cases,

p < 0.0001) (

Table 1). A similar but lower lockdown decreasing effect can be seen in accidents involving pedestrians and cyclists (13.8% vs. 22.3%), activities that are somewhat granted during the lockdown period. Conversely in 2020 there was an increase in intentional trauma caused by interpersonal violence (9.4% versus 4.9%) and suicide attempts (17.1% versus 6.4%) and in domestic accidents (20.4% versus 8.4%) compared to previous years (

Table 1,

p < 0.0001). This agree with more recent Mental Health literature. [

9,

10]

Against our expectations the trend of injuries caused by work and free time/sport activities did not undergo significant changes during 2020 lockdown if compared to previous years (

Table 1).

Analyzing the behavior over the days of the individual Mechanism of injury in 2020, it is observed that only accidents involving motor vehicles (motorcycles and cars) show a 2-phase behavior similar to that of the overall cumulative increase curve (

Figure 3); the other causes instead confirmed a more homogeneous linear trend during the whole lockdown period. This is particularly true during the first lockdown period (March 8 to April 16) when 1 patient with motor accident was expected every 3 days (

Figure 3) throughout Lombardy. Traditionally the period from March to May corresponds to the beginning of sunny days and to a greater use of motorcycles, the main cause of serious trauma with a strong proportion for each year from 2017 to 2019, in which about 1 patient/day was admitted for this cause happened in Milan metropolitan area. During the second phase (April 16 to May 8) of lockdown this trend started to resemble that of previous years with more than 1 patient/day admitted (

Figure 3).

The 2020 major trauma patients compared to previous years shows a significant increase in the average age (

Table 1,

p < 0.0002); it could be explained by the reduction in the number of road accidents, which have no significant difference in patients age during years (

Table 2).

Although the super-stratification of the sample by age, year and Mechanism does not allow conclusive deductions, a significative difference in age is observed for intentional trauma (

p < 0.025) and trauma due to daily activities (

p < 0.012), which are the main Mechanisms of injury in 2020 sample (

Table 2).

COVID-19 lockdown provided a unique opportunity to study a reversal epidemiology of major trauma, but the incidence of facial fractures in this type of patient did not show significant differences (

Table 1,

p < 0.450). This means that regardless of its causes, facial trauma affects about 1 in 5 patients with major trauma.

The sample of patients managed by the Maxillofacial Team is made up, in equal proportions, of patients with isolated facial involvement (n = 35 patients) and patients with associated major trauma (n = 36 patients).

We also wanted to analyze the influence on facial frac-tures of the Mechanism of injury and, due to the small sample size inherent the lockdown period, we have considered 3 main groups: Road accidents (with or without motor vehicles involvement), intentional trauma (interpersonal violence and attempted suicide) and Daily Activities (work, free time and domestics) (

Table 3).

Patients with facial fracture and associated major trauma are affected by high energy Mechanisms of injury and show a trend comparable to that of patients with major trauma without facial involvement (

Table 3,

p = 0.774). Those with isolated facial trauma, more frequently caused by lowenergy mechanism, instead show a prevalence of cause related to daily activity and a significantly different trend from the other 2 groups (

Table 3,

p < 0.0001).

CFI score was used as the appropriate tool to calculate facial injury severity. [

7,

8] A quarter of facial fracture patients have no treatment indications for facial injuries, according to a lowest CFI score; three quarters instead required management, which for the half of the cases was surgical and for the other half was Non-Operative Management (

Figure 4).

Nasopharyngeal swab or tracheo-bronchial aspirate positivity for SARS-CoV-2 genome and/or chest CT-scan suggestive for Corona-Virus-Disease (COVID-19) was detected in 10% of sample undergoing surgical treatment of facial injuries (

Figure 4). In these patients mean facial trauma severity was scored at 7.7 CFI points, whereas 5.9 CFI points in non-COVID-19 surgically treated patients. The only patient with COVID-19 positivity who underwent NOM for facial fractures scored 4 to CFI, the only patient with COVID-19 positivity and no treatment indication has a CFI score of 2.

Therefore we can say that COVID-19 positivity, unrelated to symptomatic respiratory distress, does not significantly influence the choice of facial injury management.

5. Conclusions

The lockdown period caused by the COVID-19 pandemic offered a unique opportunity to study the epidemiological effects on trauma, caused by a drastic change in lifestyle habits in a metropolitan area, such as that served by the Niguarda Hospital Trauma Center.

The creation of a Hub & Spoke network for time-dependent diseases has proved to be a winning choice, for the correct allocation of resources at a critical moment such as the pandemic, and also allowed the collection of data, the analysis of which would provides valuable ideas for strategic health policy choices.

The work of a Maxillo Facial Team in this context enhances the analysis from a specialist point of view, characterizing populations involved in facial trauma with different dynamics and with different epidemiological behavior. In this context, the analysis of treatment choices in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, but without systemic involvement, underlines the usefulness of a tool for classifying the severity of facial lesions, such as the CFI score.