1. Introduction

At the present time, reconstruction of large defects (bigger than 4 cm), that arise either from a primary oncologic resections or from severe craniofacial trauma, is best achieved with the use of osseous and osteocutaneous free flaps. These flaps provide well vascularized tissue, adequate structural support and soft tissue coverage, and overall help to reestablish the original mandibular shape and its function. However, these types of reconstruction continue to be challenging due to the fact that the anatomy of the craniofacial structures is highly complex and intricate. [

1,

2]

In view of this scenario, it is very important to evaluate the type of defect and its characteristics preoperatively, in order to decide what are the best reconstructive options. A primary reconstructive treatment must try to establish in the most accurate way the dimensions and proportions of the initial defect in an attempt to decrease the need for secondary corrective surgeries. We have many tools nowadays to help us improve the accuracy of these reconstructions and shorten surgical times, such as the 3D computer-guided surgical planning. Despite the use of these tools and guides that are able to minimize the margin of error as far as the length, position and direction of the bone segments during the reconstruction, a perfect outcome cannot always be guaranteed. [

2,

3,

4] Subsequent malocclusion can be the result of inadequate positioning and fixation of the bone segments during the primary reconstruction. It can also be a secondary of an infectious process, bone resorption or an inadequate 3D computer-guided surgical planning. Correction of these conditions will depend on the particular subsequent alteration, requiring orthognathic surgery in cases with large discrepancies that cannot be corrected with orthopedic traction, orthodontic therapy or prothesis. [

4]

At present, there is limited information in the medical literature about this subject and about its short-term and long-term outcomes following postoperative concerning to the occlusion after primary mandibular reconstruction and the malocclusion management with orthognathic surgery in these cases where this complication is present.

In this article we describe the experience in the management of malocclusion after mandibular reconstruction with free fibula flap in the department of Plastic Surgery at the Hospital San Jose´, Bogota´, Colombia.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a descriptive retrospective case series in which we reviewed 6 cases of severe malocclusion, following free fibula flap mandibular reconstruction, that required corrective orthognathic surgery at San Jose Hospital, in Bogota´, Colombia, between January 2010 and December 2019. We evaluated the demographic data, operative techniques, corrective methods and the postoperative results.

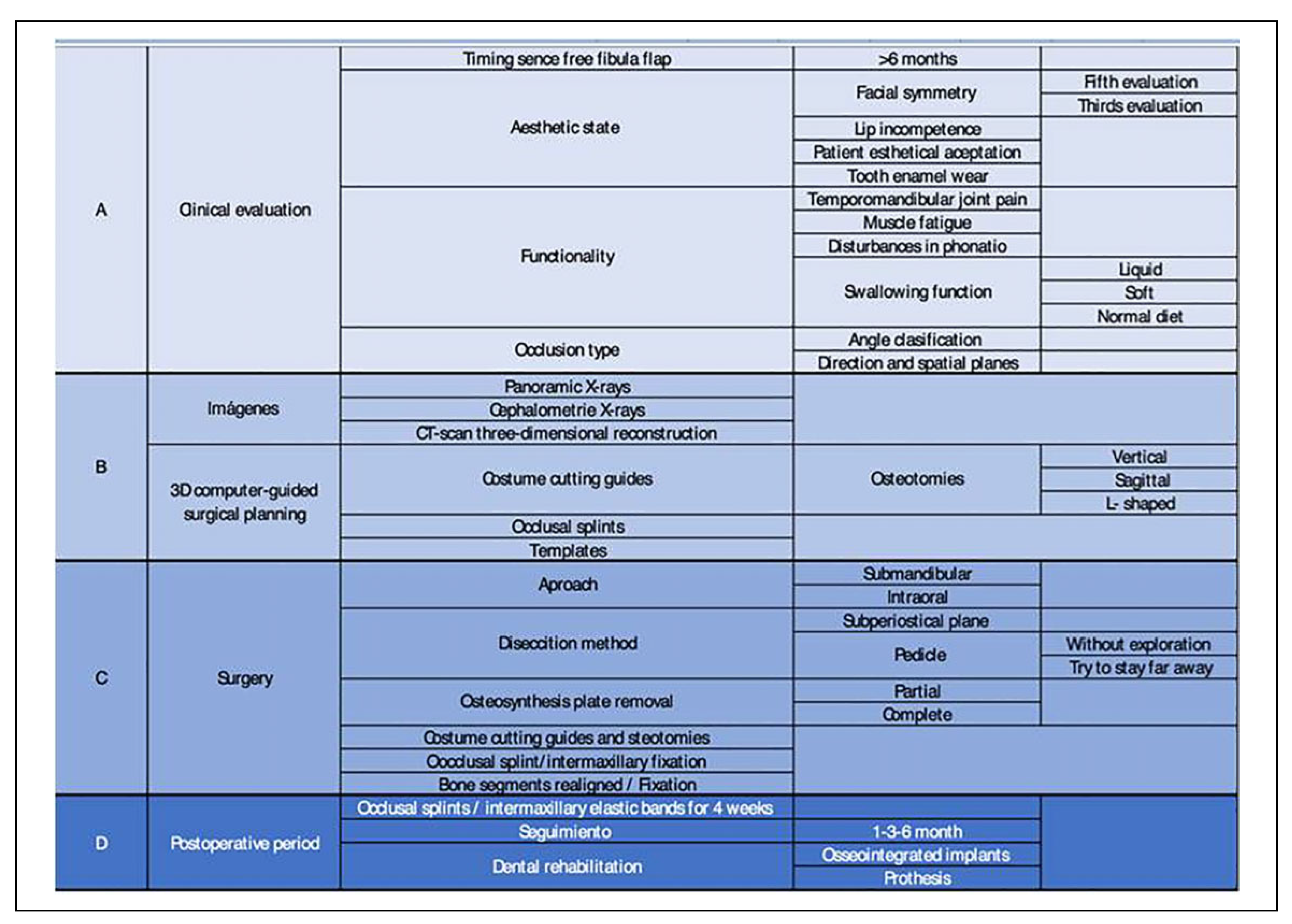

Procedure

A complete clinical evaluation was carried out in each patient. Facial symmetry was assessed based on the aesthetic rule of fifths and thirds, lip competence was also assessed, as well as the patient’s self-perception of his/her aesthetic defect; functionality was explored through the presence of tooth enamel wear, temporomandibular joint pain, muscle fatigue, disturbances in phonation and swallowing function, the latter being evaluated according to the type of diet tolerated by the patient (liquid, soft or normal diet).

The type of occlusion presented by each patient was classified according to Angle classification and its dental relationship in the 3 spatial planes: anteroposterior, vertical and horizontal; all of this planes which were subdivided in anterior and posterior planes. Also, the occlusal plane was analyzed in relation to the horizontal facial plane.

Patient satisfaction, tooth enamel wear and lip incompetence were considered minor selection criteria. Mayor or absolute selection criteria were timing since the free fibula flap >6 months, aesthetic distortion, or phonation and swallowing alterations.

Prior to corrective bone surgery, a complete image study of the patient was obtained. In all cases it was necessary to have panoramic X-rays, cephalometries and/or 3-D facial reconstruction CT scans. 3-D computer-guided surgical planning was used to create surgical cutting guides, templates and occlusal splints in all the patients that underwent corrective orthognathic surgery.

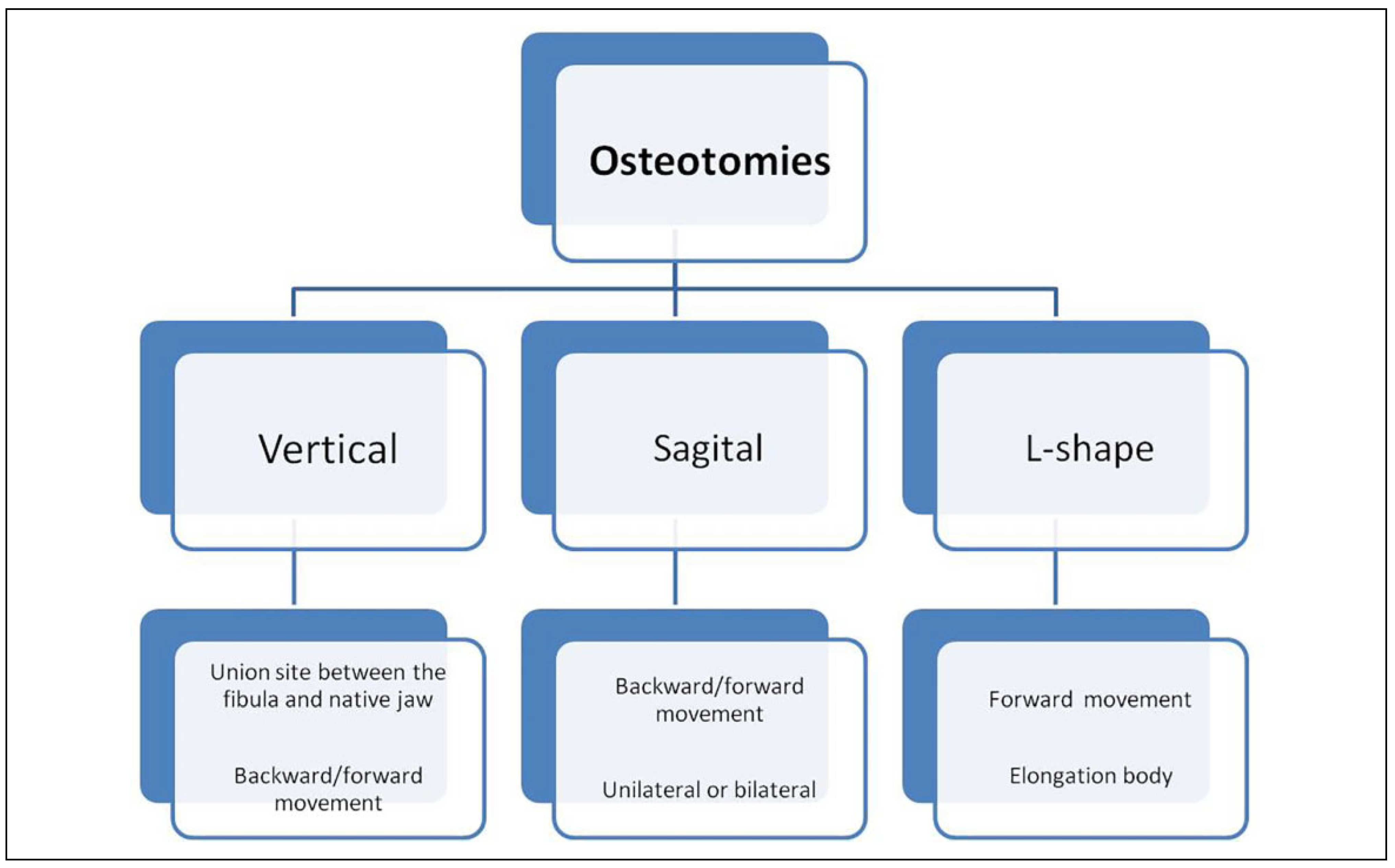

We used an intraoral or submandibular approach, depending on the necessity of each patient. The subperiostial plane was accessed without performing any surgical exploration and with care not to disturb the vascular pedicle, and in this way the fibula flap was exposed. Then, the osteosynthesis plate, initially placed for the primary mandibular reconstruction, was removed, and cutting guides were placed to guide the needed osteotomies. These osteotomies could be vertical, sagittal or L-shaped, along the flap or at the union site between the fibula and the native mandible, either unilaterally or bilaterally. The choice of a particular osteotomy was made on a case by case basis, and always making sure that the contact surface between the different osteotomies was of at least 1 cm to provide adequate fixation stability (

Figure 1). Following the osteotomies, an adequate dental occlusion was achieved using an occlusal splint, the intermaxillary fixation was performed with the help of screws and wire. The bone segments were aligned and fixated using miniplates or lag screws. Once the fixation of the bone segments was achieved, the intermaxillary fixation was removed. In some cases, osteogenic distraction was needed in order to enhance the length or width of the reconstructed mandible and to improve the occlusion and guarantee a proper dental rehabilitation.

During the postoperative period, the occlusal splint was placed in position using intermaxillary elastic bands to guide the bite; the elastic bands were left in place for 4 weeks. Follow-ups were done at 3 and 6 months and consisted of a clinical evaluation and panoramic X-rays.

3. Results

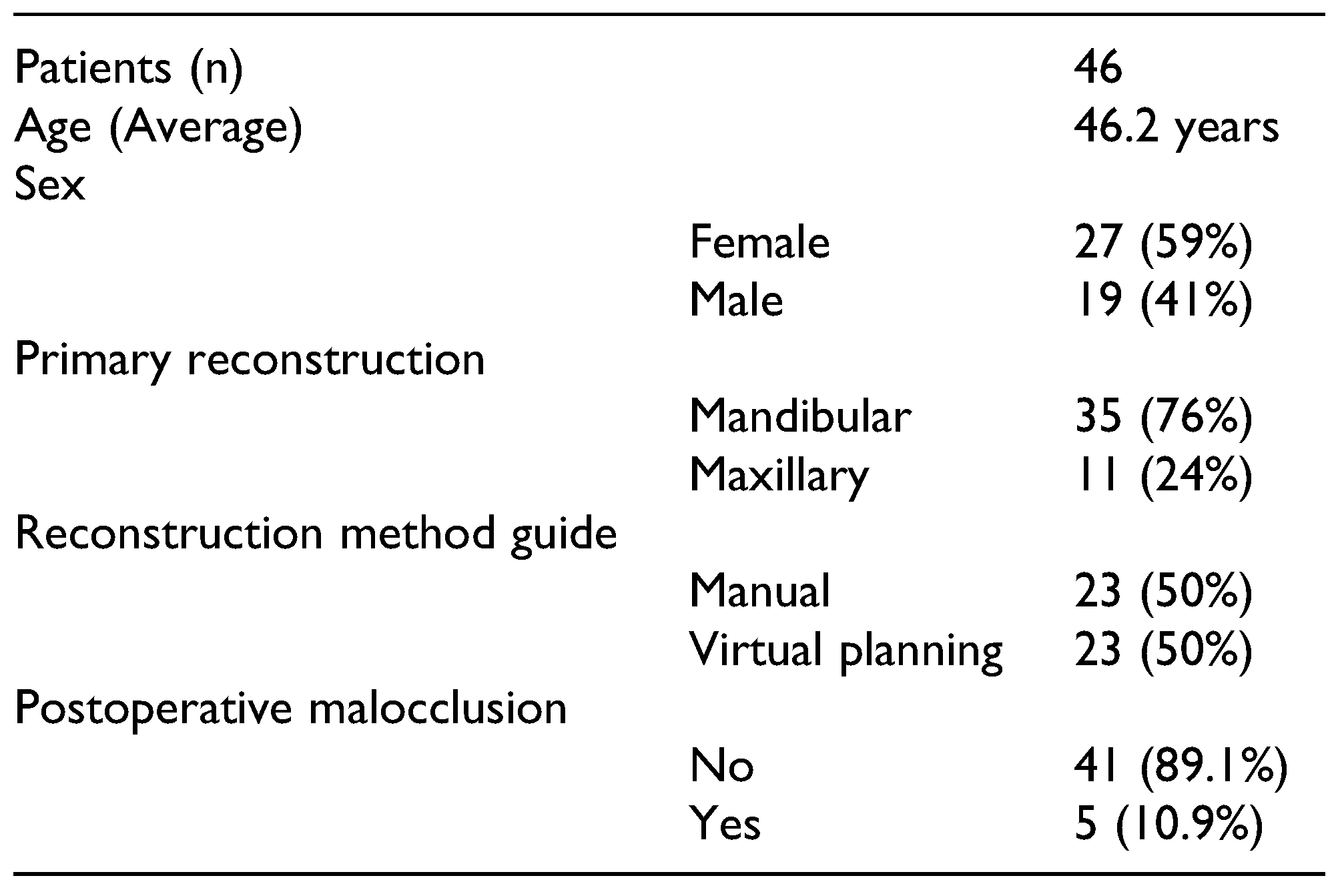

Between January 2010 to December 2019, 35 mandibular reconstructions and 11 maxillary reconstructions with free fibula flaps were performed at the San Jose Hospital in Bogota´. Of these patients, 59% were women and 41% men, with a mean age of 46.2 years, with the youngest patient being 6 years old and the oldest 70 years old. 23 patients were reconstructed following 3D computer-guided surgical planning, 1 of which developed malocclusion. The other 23 patients were reconstructed following a manual method, 4 of which developed malocclusion. All of these 5 patients who developed malocclusion (10.9%) required orthognathic surgery for its correction (

Table 1). One (1) other patient from another institution was later added, making a total of 6 patients that underwent surgical correction. No patients that underwent a maxillary reconstruction developed malocclusion, which is why the patients who underwent a maxillary reconstruction were excluded from our analysis.

100% of the patients in this case series underwent a primary mandibular reconstruction, 4 of which were due to tumoral pathology and 2 of which were due to an infectious pathology. 4 of them required a hemimandibulectomy and 2 of them a partial subcondylar mandibulectomy. The method of reconstruction in 4 of these patients was a manual planning method with acetate templates or hypodermic syringes, while the other 2 patients underwent a computerassisted three-dimensional planning (

Table 2).

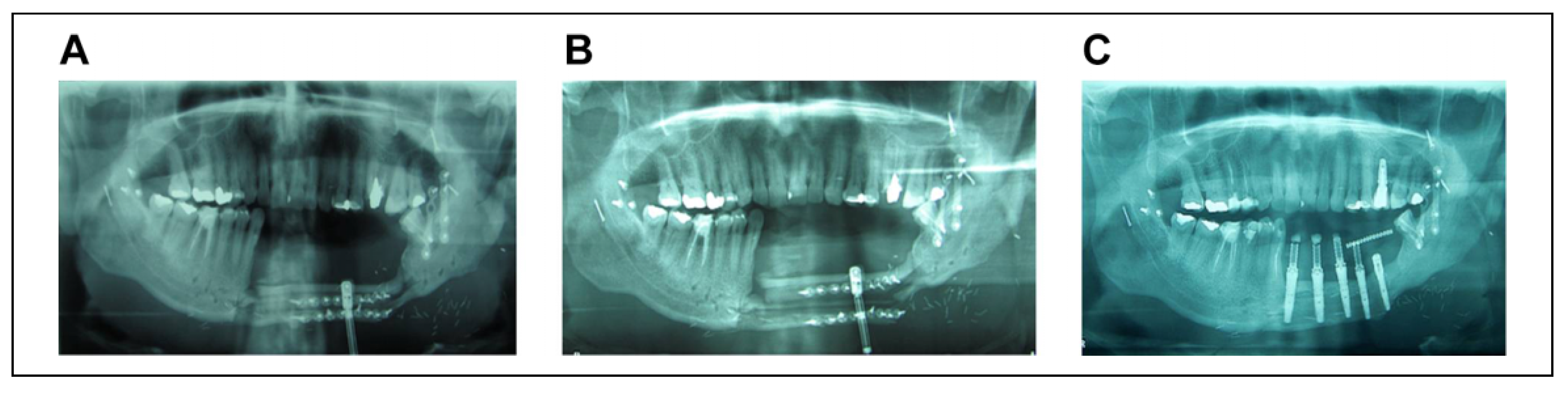

The patients who had a deficit of bone tissue in a vertical or transverse plane, underwent osteogenic distraction in order to correct either the length or width of the bone, respectively. Once an adequate bone measure was achieved and the distractor was removed, these patients underwent placement of osseointegrated implants (

Figure 2) at a later stage after their rehabilitation.

As for the osteotomies, unilateral vertical osteotomies at the level of the junction between the fibula flap and the jaw were made in 3 patients. Bilateral sagittal split osteotomies were performed in 2 patients and L-shaped osteotomies were done in 1 patient. The fixation method was based on miniplates in 3 patients and lag screws in the other 3 patients (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

During follow-up, all patients achieved an adequate occlusion correction with a complete bone consolidation of 100%. There were no complications documented in the perioperative period or during follow-up.

Clinical Case

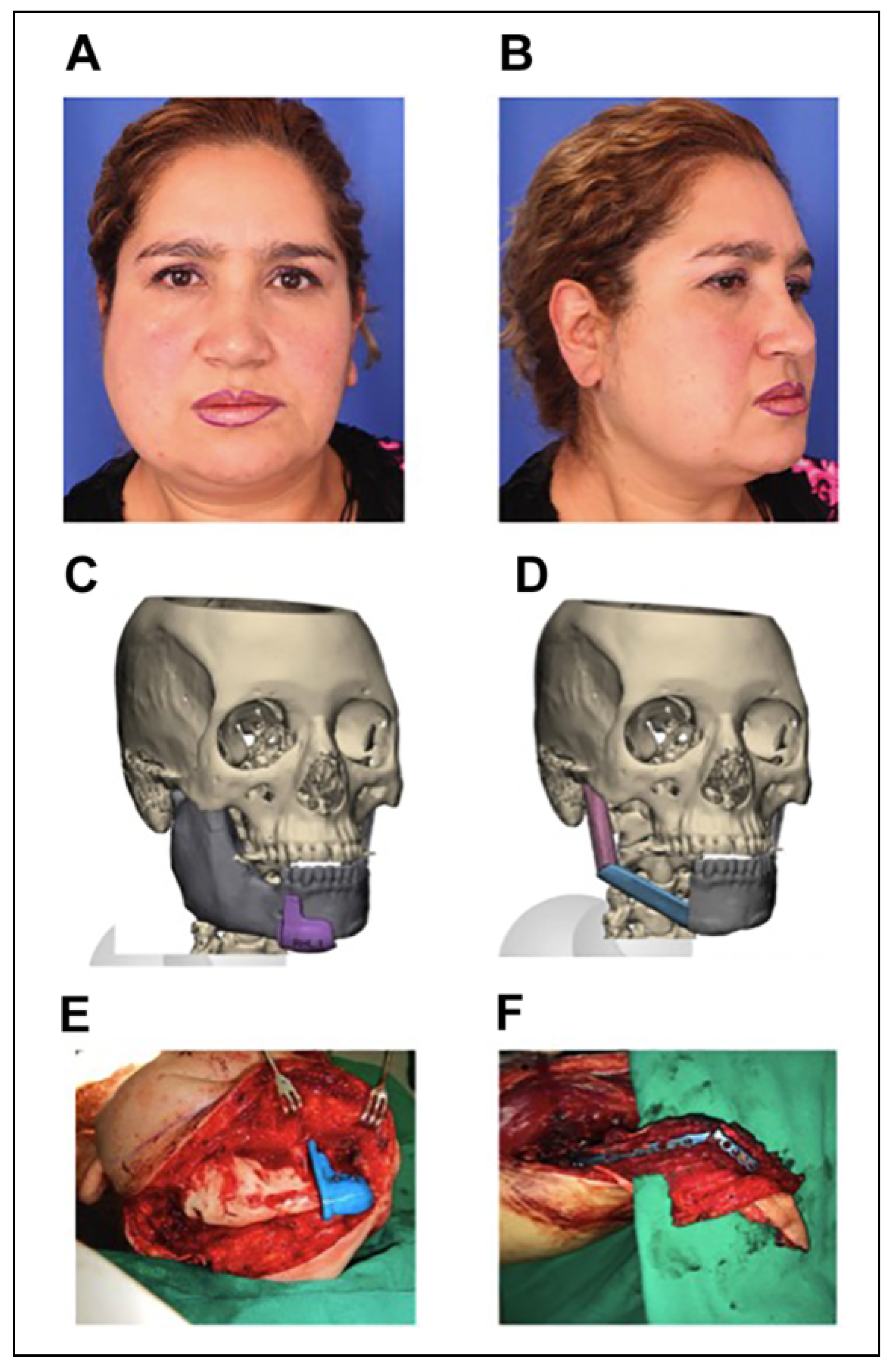

50-year-old woman with a history of 4 years of progressive growth of a mass in the right mandibular area that could be intraorally palpated on the body, angle, branch, coronoid process and right condyle of the mandible, with evidence of an angle class III malocclusion, inferior midline deviation of 4 mm to the left and crossbite. A biopsy of such mass was performed which reported a giant cell tumor. On September 2018, the tumor was resected and a mandibular reconstruction with a free fibula flap was performed. Despite 3D computer-guided surgical planning, the length of the bone segments was not appropriate since the cutting guides did not fit the right fibula, because the cuts had been designed based on the left fibula; because of this, a manual approach had to be used instead of the 3D computer-guided surgical planning (

Figure 3). After 1 year, malocclusion was documented, and on November 2019 she was taken for orthognathic surgery using 3D computer-guided surgical planning to create surgical cutting guides, templates and occlusal splints for the procedure. We performed an intermaxillary fixation, L-shaped osteotomy of the body of the mandible over the free fibula flap with reduction of the bone segments, which were fixated with miniplates, leaving a contact surface of 1 centimeter. An adequate postoperative occlusion was successfully achieved. (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

The reconstructive method of choice for large mandibular defects (>4 cm) is osseous free flaps. The ideal characteristics of these free flaps must be determined by an appropriate bone quality, optimal length and the possibility of oral rehabilitation afterward. Free fibula flap have been the reconstructive gold standard specially in mandibular defects due to its versatility, bone length and pedicle length. [

1,

3]

With the advent of technology, 3D computer-guided surgical planning optimized mandibular reconstruction, leading to shorter surgical time, better results with a higher degree of accuracy and assertiveness regarding the established goals in each patient and improving aesthetic and functional results. However, considering multiple factors, this tool does not guarantee a perfect result concerning patient’s occlusion in the postoperative follow-up. An unsuitable planning due to CT Scan images incorrectly taken or rotated, planning based on the opposite side, result in inaccurate surgical templates that lead to larger or shorter bone segments than desired, ensuing unexpected outcomes. [

2]

The postoperative evaluation and follow-up must be guided toward functional and aesthetic results, with special attention to the facial symmetry, occlusion, speech and masticatory function. [

1,

2] Some of the multiple factors that can affect the results in mandibular reconstruction are an inadequate or insufficient intermaxillary fixation, faulty occlusal splints, alterations in the contouring and bending, or misplacement of the mandibular plates, misplacing the flap, the displacement of the condyle or flap proximal stub (which is remodeled and adapts adequately to the glenoid fossa) outside the glenoid fossa. Other factors that influence this complication are fractures of either the mandible or the osteosynthesis material, infection, bone resorption and fibrosis consequent soft tissue retraction. [

4]

Malocclusion generates both facial asymmetry and functional alteration leading to mandibular wear and/or ankylosis. [

1,

3] Orthognathic surgery is required when patients develop occlusal alterations with severe discrepancies. This allows an improvement in the biomechanical function between bone and soft tissues as well as facial appearance. Orthognathic surgery in patients that have undergone mandibular reconstruction with free flaps was initially described by Chang et al, who performed a vertical osteotomy in the union site between the fibula and mandible. [

4] Other authors describe the use of unilateral or bilateral sagittal osteotomies. [

2,

5,

6,

7] Additionally, other authors describe the “L” shaped osteotomies. [

7] The goal of orthognathic surgery on free flaps is to correct the malocclusion by improving the contact area between the flap and the mandible through a rehabilitated dental arch.

4.1. Clinical Evaluation

It must be oriented towards the search of facial asymmetries, patient’s functional status assessment as in speech, eating, swallowing and oral opening. The patients must always be evaluated by a multidisciplinary team that includes a craniofacial plastic surgeon, microsurgeon and odontology team consisting of orthodontist, oral rehabilitator and periodontist. [

3]

4.2. Clinical Imaging

The realization of anteroposterior and lateral cephalometries, panoramic x-rays, standardized photographs, study models and three-dimensional reconstruction CT scan images is suggested. [

2]

4.3. Preoperative Planning

It must be based on imagenologic studies, dental models and 3D computer-guided surgical planning.

Depending on these elements, vertical, horizontal or both planes, (either anterior and posterior) can be modified to correct the alteration. [

5]

The pedicle of the free flap must be taken into account for any secondary intervention. Some authors consider that 1 year after surgery the flap is autonomous and the pedicle may not be preserved, however, our recommendation is to avoid the surrounding area of the anastomosis, and to wait at least 6 months for any secondary procedure. [

5,

6]

4.4. Mandibular Osteotomies

The design of the osteotomies on the mandible will depend on the dimensions of the free fibula flap previously performed and the desired movement in the different planes (vertical or horizontal). [

7]

Sagittal osteotomies allow backward and forward movement through sliding, increasing contact between surfaces and maximizing bone stability, repositioning the bone segments and improving the facial symmetry. [

2,

7] Vertical osteotomies can also be performed, removing or not the plate placed in the union site between the fibula and the mandible. [

4] L-shaped osteotomies are performed parallel to the vector of movement, adding 1 cm when possible to increase the contact surface, improving stability. [

7]

The type of bone flap used must be taken into account; the recommendation on free fibula flap is to perform vertical or L-shaped osteotomies with limited subperiosteal dissection to prevent devascularization. [

7]

Occlusal splints and intermaxillary fixation must be performed during surgery, this allows an appropriate alignment and fixation between the flap segments and the mandible, so a correct occlusion can be achieved. [

1,

4,

6,

7]

4.5. Osteogenic Distraction

This procedure can be performed as the definite treatment or as the initial step in the management of malocclusion; it’s indicated in the cases where there is an important bone loss and subsequent vertical shortening, and the osteotomies with the fixation methods are not enough for restoring the bone dimensions. It can be performed in either vertical or horizontal plane. Other orthognathic procedures can be performed if needed once the process of osteogenic distraction is completed; in case an adequate occlusion has been achieved dental rehabilitation with osseointegrated implants would be the next step (

Figure 1).

4.6. Main Aspects of Management

There must always be a preoperative planning based on diagnostic images, panoramic x-rays, cephalometries, CTscan and dental models. Nowadays, computer-guided surgical planning is the best option available and must be used. During the procedure, occlusal splints and intermaxillary fixation must be used to guide the occlusion.

Orthognathic surgery in patients with previous mandibular reconstruction should be performed at least 6 months after the primary surgery, preventing vascular damage during dissection. Oral rehabilitation should begin 3 to 6 months after orthognathic surgery. Teeth over the cutting line of the osteotomy must be removed in order to avoid bone loss and instability, therefore providing the ideal conditions for bone healing. Vertical osteogenic distraction should always be considered for better stability and support of the osseointegrated dental implants [

5,

7] (

Figure 6).

5. Conclusions

The evolution of reconstructive surgery makes possible the reconstruction of complex defects. Mandibular primary reconstruction can lead to unsatisfactory aesthetic and functional results such as malocclusion with severe discrepancies that require performing orthognathic procedures in order to correct the occlusal alteration and facial asymmetry, providing the possibility of oral rehabilitation.

Secondary procedures should be delayed for at least 6 months in order to prevent damage to the vascular pedicle of the flap; osteotomies must be selected according to desired movement, and bone contact surface must be of 1 centimeter to provide stability.

Currently, reconstructed patients should undergo dental rehabilitation with osseointegrated dental implants. For this reason, it is necessary to have a proper maxillomandibular relationship.