Introduction

Violence against women is a challenge to public health; it reflects gender inequality and is a violation of women’s human rights.[

1] It generates emotional, psychological, and physical consequences and can affects women of all ages, socioeconomic classes, cultures, and religions.[

1] The most common cause is the domestic violence, which is realized by their intimate partner, more than violence in the streets. A significant progress has been made in Brazil concerning the establishment of the Women’s Protection Police Station. But even with all public politics, there are an expressive homicide data. Espírito Santo is considered one of the most violent states with homicide tax, over than a medium Brazil tax. Other very important aspect is the different races, where the black women have the homicide tax significantly higher.

In 1993, the United Nations defined violence against women as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women.” Male aggressors commonly have personal or intimate relationships with the women they abuse. Studies based on data from the World Health Organization (WHO, 2002) report that between 10% and 69% of women worldwide have experienced physical violence from an intimate partner at some time in their lives.[

2]

The WHO (2019) defines violence as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.”[

3] Violence is a social issue and is therefore not exclusively associated with any specific field within health care. In Brazil, there is no question that society has made progress on combating violence against women in recent years. In 2003, Brazil passed Law No. 10.778, which made it mandatory for health care professionals in both public and private care to report suspected or confirmed cases of any kind of violence against women. Article 5 of the law outlines the consequences for medical professionals who do not comply.[

4] Health care professionals in the country therefore need to be properly trained in treating trauma, as well as in being receptive to victims, giving victims access to support services or protection, counseling victims on the importance of reporting the crime, and filing the mandatory report.[

5] Giffin also emphasizes the importance of incidence and prevalence data on violence against women, as well as of training health care professionals on how to counsel and support victims.[

6]

However, in a ranking on femicide frequency worldwide, Brazil came in fifth place out of 83 countries, behind only El Salvador, Colombia, Guatemala, and Russia. The survey found that a woman is killed in Brazil every 2 hours, most frequently by a man who is or has been her intimate partner. According to a national study from 2015, the Brazilian state in which violence against women is most frequent is Roraima, followed by Espírito Santo. The state capital in which violence against women was found to be most frequent was Vitória, the capital of Espírito Santo. The city of Serra, where the current study took place, came in 14th place out of all of the cities in Brazil.[

2]

It is crucial to understand the details of facial trauma, since these injuries negatively affect victims’ social lives and emotional states, leave scars and other sequelae, and often marginalize victims from society.[

7] Facial trauma worsens workplace performance, increases absenteeism from the workplace, and makes it more likely that victims will lose their jobs.[

8] It is therefore clear that, in addition to emotional damage, facial trauma creates a socioeconomic problem and increases victims’ use of social services.[

7,

8]

Violence against women is not new; however, it is only relatively recently in Brazil’s history that measures have been taken in an attempt to reduce these crimes. In 1940, the Brazilian penal code characterized physical aggression against a woman as a punishable crime. In the 1980s, Brazil’s first women’s police stations were implemented as a safe space for women to report crimes and ensure legal support.[

9] In August 2006, Brazilian Law No. 11.340 went into effect. Known locally as the Maria da Penha law, it has sought to increase the terms of punishments for crimes against women.[

2] Article 5 of the law defines domestic and family violence against women as any action that causes death, injury, or physical, sexual, or psychological suffering.[

4] After the implementation of the Maria da Penha law, crimes against women continued to increase in frequency, but at a slower rate: the national increase in femicide decreased to 2.6% annually. In 2015, Brazilian Law No.13.104 went into effect in the country. Known as the Femicide Law, it classifies violence against women as a heinous crime and defines it as aggravated when the violence is committed in cases of vulnerability, such as against minors, during pregnancy, or in the presence of children.[

4]

The face is the most evident, exposed, and unprotected area of the body; an individual’s face and facial expressions are closely tied to their identity.[

10] When an aggressor leaves a victim’s face disfigured, the disfigurement affects the victim’s self-esteem and creates both physical and emotional scars.[

10] Trauma to the face may result in cosmetic deformities and a loss of functional abilities such as chewing and swallowing, changes to speech or breathing, pain, changes in dental occlusion or a loss of teeth, as well as damage to soft tissue, such as ecchymosis and abrasions.[

11] According to Halpern, injuries to the head, face, and neck may represent a marker of intimate partner violence.[

12]

The objective of this study was to investigate the number of facial fractures and the patterns between these fractures and women who experienced physical aggression from intimate partners between 2013 and 2018 and who were treated at a public tertiary referral hospital for trauma in the Brazilian state of Espírito Santo.

Methodology

This was a retrospective, observational, descriptive, and longitudinal epidemiological study of patients with maxillofacial trauma treated by the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Traumatology of Dr. Jayme Santos Neves State Hospital in the city of Serra, Espírito Santo State, Brazil. In this study, patient records over a 6-year period (February 1, 2013 to December 31, 2018) were analyzed.

This study was approved by the research ethics committee of São Pedro Integrated Colleges (FAESA) under ethics evaluation submission certificate (CAAE) registry number 73203017.0.0000.5059. The study was exempt from the use of an informed consent form (ICF) due to its retrospective nature; only relevant information was obtained from patients’ medical records, and patient identity was kept confidential.

Patients whose medical records were not properly completed were excluded from the study, as were patients with facial trauma who had refused treatment and patients with facial trauma who were not evaluated by the hospital’s oral and maxillofacial surgery and traumatology team.

Data on patient age, as well as on the etiology, nature, and type of injury were collected. The maxillofacial fractures were organized by their etiological factors into motor vehicle accidents, motorcycle accidents, falls, physical aggression, and gunshot wounds. The fractures were also divided into 2 groups based on the location of the fracture: the mid and upper thirds of the face and the lower third of the face. The fractures of the mid, upper and lower thirds of the face were investigated.

Other data collected included the length of time between the trauma and treatment, length of preoperative and postoperative hospitalization, prevalent signs and symptoms, and the days, months, and years in which the injuries occurred.

Discussion

This study evaluated the etiology of facial trauma in women and found falls to be the most commonly reported cause (27.6%), followed closely by physical aggression (21.2%) and motor vehicle accidents (10.2%). Because etiology was self-reported by the victims, there is the possibility that the victims were hiding the true causes of their injuries due to fear or shame. According to Silva et al, it is not uncommon for the aggressor to accompany the victim to the hospital in an attempt to intimidate her or prevent her from reporting the true cause of the trauma.[

5] The aggressors may aid in or insist upon hiding the signs of aggression in order to avoid being punished through the Maria da Penha law

When women are abused by men, some do not report it or answer health care professionals’ questions honestly, often because they are financially dependent upon or emotionally involved with the aggressor.[

13,

14] For these reasons, it is difficult for medical professionals to identify victims and refer them to support services or protective care. Thus, the number of violence victims may be smaller than the reality. Another complicating issue is the victim’s emotional fragility at the time of care.[

11] This information shows the importance of a multidisciplinary team to lead with the patient in this specific situation, like social and psychological assistance, in addition to medical and dental treatment, to provide more comfort and safety for the victim.

The most common age range of the victims in this study was between 20 and 29 years (33.9%), findings which are consistent with those reported by Silva.[

15] The prevalent victim ethnicity in this study was mixed race (50.0%), followed by black (17.7%); these data may vary depending on where studies are performed.[

8] But, in general, the violence against women is a social issue that does not correlate with any specific social class, race or ethnicity, religion, age, or education level.[

4]

In 2019, a study in Brazil showed a significative increase (30.7%) in Brazil women’s homicides numbers from 2007 to 2017.[

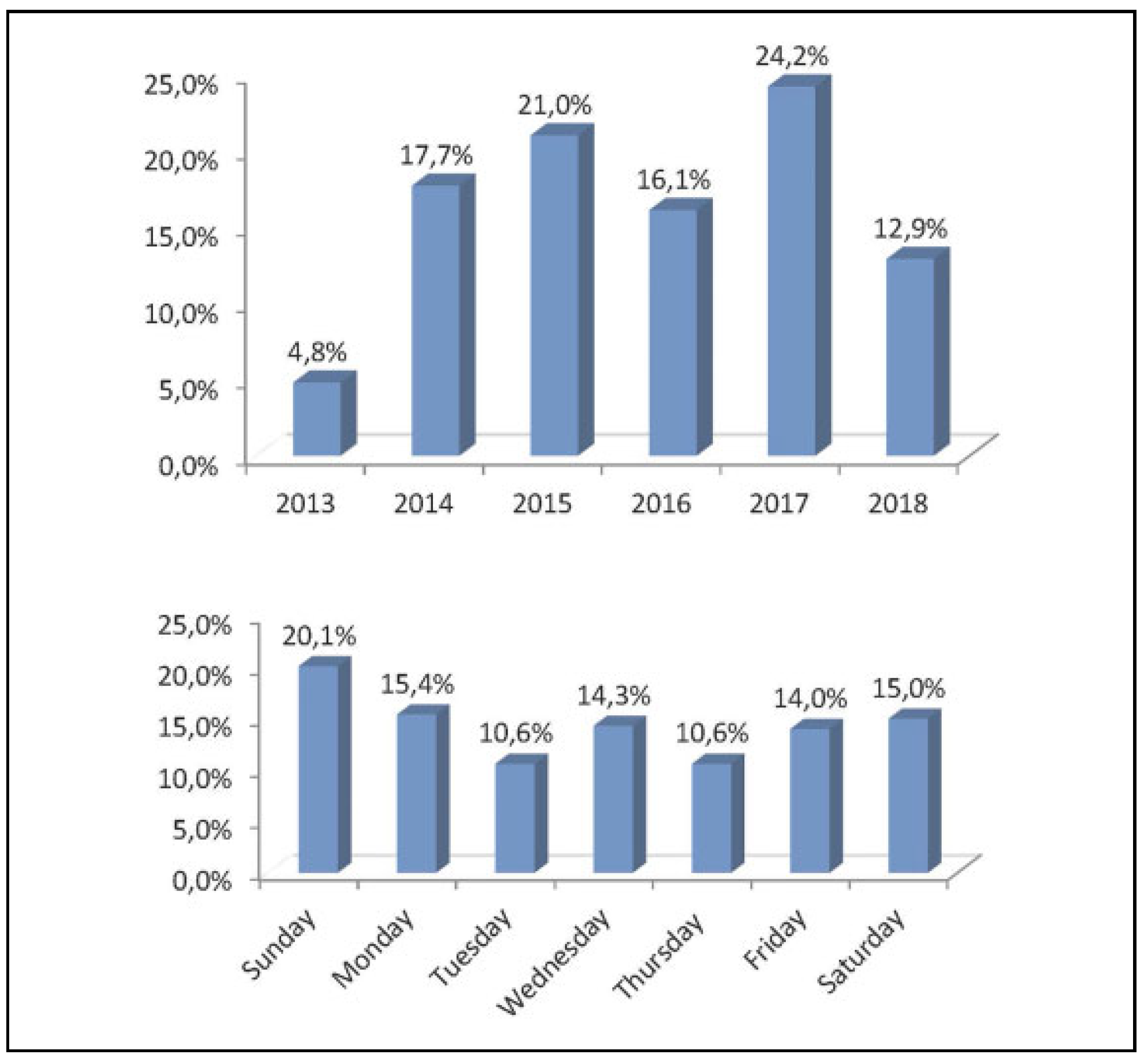

16] The same study shows that the Espírito Santo State had the feminicide highest rates in the country during 2012 and actually, the state is in the seventh place between the other states, what means a reduction in lethal women violence in the state probably because of the various public policy implemented by the government. This article showed that more women were treated with face trauma in 2017. These numbers contrast the data presented in other study,[

17] what is probably related with the public policy that made the women more stimulated to report the aggressor and search for treatment. As soon as the patient have the hospital care, the professional must notify the aggression against the woman, this attitude is extremely important, because these notifications can generate early penalties for the aggressor, preventing lethal traumas.

Another important finding was that, when organized by the day of the week on which men carried out physical aggression against the female victims included herein, the findings corroborate a study by Castro et al, in which physical aggression was most likely to occur on the weekend (20.82% on Sundays and 14.35% on Saturdays).[

11] The higher incidence of physical aggression on the weekends coincides with the days on which aggressors are more likely to be intoxicated, as well as with the days on which victims have fewer options for escape.[

5,

18]

The length of time between the trauma and the initial treatment may be prolonged due to the victim’s fear, shame, financial dependence on or emotional relationship with the aggressor, or if the aggressor prohibits the victim from seeking medical attention. These factors may explain why 66.1% of the women treated in this study waited up to 1 week to seek medical attention for their trauma. Malachias found that women tended to seek medical care a few days after the incident in an attempt to hide the true cause of the trauma; this delay often causes permanent physical sequelae.[

4]

Marano et al demonstrated an epidemiologic data from the same hospital from 2013 to 2017.[

19] A total of 428 patients with facial trauma were included in this study, among these patients, 82 were women. The main etiologies were traffic accident, followed by fall and physical aggression. Considering the physical aggression, the author highlights that most of the women (80%) had suffered aggression by men with the majority being their partners or past partners.

In the current study, we maintained the same data, in which 80% of the aggressions, the women’s partner or the past partner was the responsible. For other cases (20%), we were unable to identify who the aggressor was.

The high costs of health care treatments, legal fees, victim absenteeism from the workplace, and extended preoperative and postoperative hospital stays are all a burden on taxpayers.[

7] According to the United Nations, violence against women costs 1.5 trillion dollars globally per year through the expenses involved in caring for women, the consequences of aggression, and the enforcement of related laws. In Brazil, the country’s public health care system (SUS) treats an estimated 147,691 female victims of sexual, physical, or psychological violence per year and spends an annual average of 5 million Brazilian reais (1327 USD) on hospitalization alone.[

20]

Extended hospitalization increases hospital expenses. In the current study, 35.5% of the women required hospitalization before their procedures and 54.8% required postoperative hospitalization for a period of up to 7 days. This extended preoperative hospitalization may be explained by the fact that some of the victims waited to seek treatment and were thus required to wait for their edema to be treated before surgery could be performed. Another factor is the presence of concomitant injuries that may increase the risk of death, such as neurological damage. According to data from the Brazilian Department of National Public Health Care Data (DATASUS), the average cost of hospitalization per patient in the southeastern region of the country is BRL$1402.01 (US$372), an expense which could be reduced if funds were focused on prevention and awareness campaigns (Ministério da Saúde 2019).

Facial trauma is often caused by an aggressor punching, hitting, or kicking a victim. When aggressors cause cosmetic or functional damage to the victim’s face during this trauma, psychological consequences for the victim are common.[

18] A study by Saddki et al[

21] found a predominance of injuries to the maxillofacial region resulting from intimate partner violence, followed by injuries to the limbs (47.9%). The authors report that the injuries to the limbs are likely the result of victims’ natural tendency to defend themselves from aggressors during an assault. Another study in Rio de Janeiro researched men and women involved in intimate partner violence using data from police reports. They found that aggressors were most likely to punch victims in the face and to damage victims’ eyes and teeth.[

8]

A study performed by Leles et al[

22] found that the highest incidence of facial injuries involves the nasal cavity, followed by the zygomatic complex and the orbital region. Arasarena et al[

23] also report that, in cases of physical aggression against women, nasal fractures are the most common injuries. The current findings corroborate this study, since isolated nasal fracture was most prevalent among the patients included herein (21 patients; 39.1%). This major nasal fracture prevalence is a different pattern when compared with the other types of etiologies, which we have shown in this study, such as falls and traffic accident. In those cases, the zygomatic orbital complex fracture was more frequent, with 68% and 65.7%, respectively; however, all trauma cases can be associated with nasal fracture. This frequency may be explained by the position of the nose on the face and its greater exposure to trauma. A study in 2011 reported that the high incidence of nasal fractures is likely the result of the relatively low amount of force required to fracture this relatively thin bone of the face.[

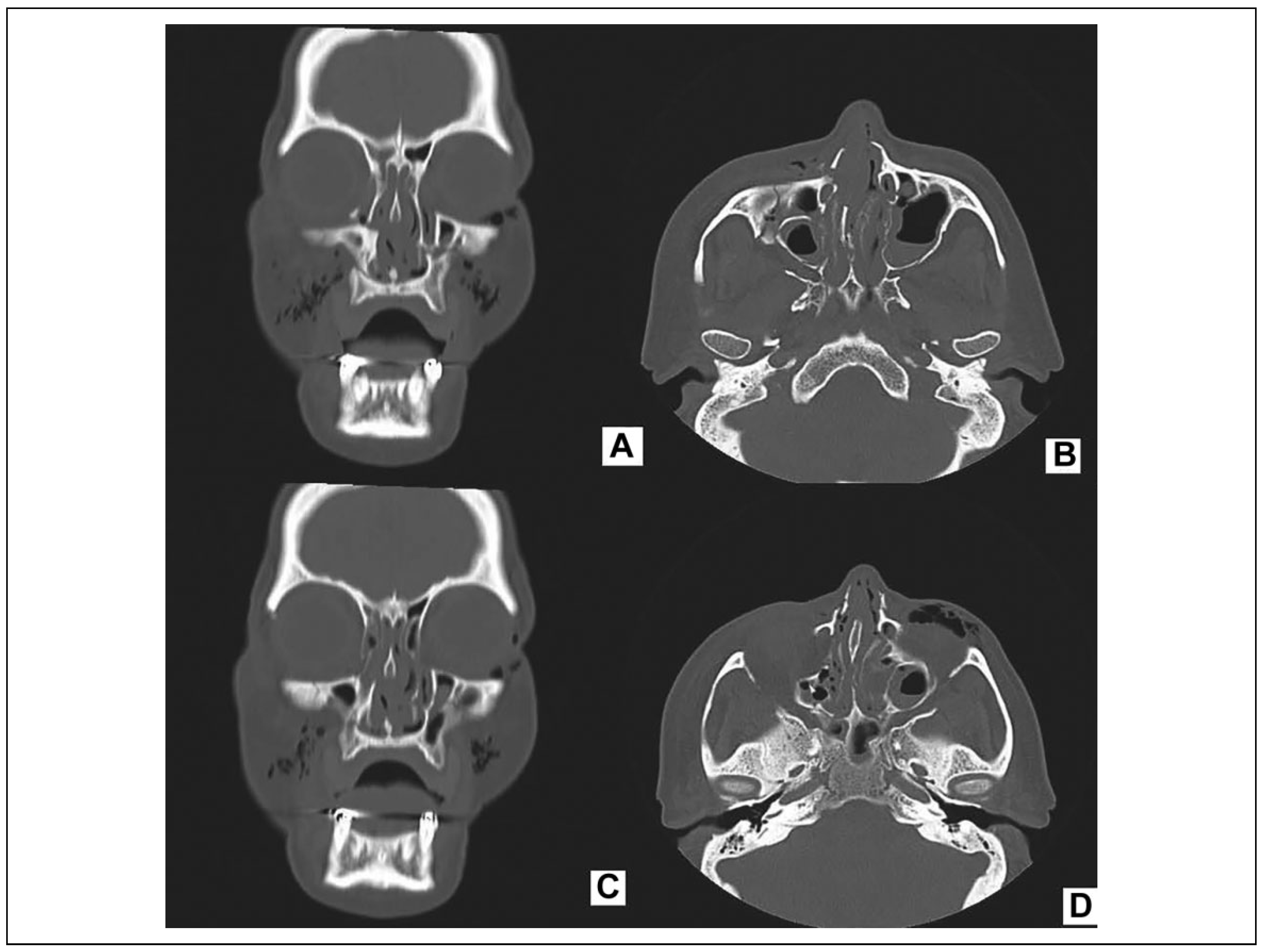

24] Exactly, what was seen in this current study, physical aggression, is generally considered to be a lower energy trauma; thus, the possibility of zygomatic trauma is smaller in this case (

Figure 3). Low-energy trauma should rely on meticulous clinical examination, affecting the extension of imaging, type of intubation, and future surgical approaches. High-energy trauma requires total body CT.[

25]

These interconnection between trauma energy and the fracture are important to help the surgeon to presuppose the etiology and to identify aggression cases, even if there is an omission from patient. The professional always must report a suspect case of aggression against women.

The most commonly reported signs and symptoms of physical aggression to the face are abrasions, ecchymosis, penetrating injuries to the face, edema, and restricted mouth opening.[

13,

26] These cosmetic and functional damages were found in the patients in the current study; the highest incidence was of edema (56.5%), periorbital ecchymosis (35.5%), deviated septum (22.6%), and hematoma (16.1%). Signs and symptoms that were observed at a lower incidence were penetrating injuries to the face (11.3%), abrasions (12.9%), and epistaxis (8.1%). However, these data may vary between studies due to the delay at which women seek treatment; the signs and symptoms recorded in a patient record vary depending on the time between the aggression and care.[

5] Some studies have found that the teeth are also commonly damaged; the most common dental fracture is of the maxillary central incisor.[

11] In this study, edema and periorbital ecchymosis were the most common signs, which were present in 92% of the cases.

The women population awareness looking for treatment, as soon as possible after the aggression is important because can avoid more serious lesions or even lethal lesions in the future. Facial trauma may involve soft tissue, bone, paranasal sinuses, eyes, teeth, and in cases in which the aggressor also injures the cranium, neurological damage. It is therefore important that trauma patients be initially treated by a multidisciplinary team involving ophthalmology, plastic surgery, oral and maxillofacial surgery, and neurosurgery in order to better ensure a correct diagnosis, as well as adequate and effective treatment.[

4,

27,

28]