Abstract

Purpose: Concomitant ophthalmic injuries are common in patients with facial fractures, though frequency varies widely in the literature. Major ophthalmic injuries can have drastic consequences for patients, and permanent visual impairment cannot be prevented in all cases. This study analyzed the frequency and distribution pattern of associated ophthalmic injuries in patients who received operative treatment for fractures of the midface. Material and Methods: The clinical information system was searched for patients with midface fractures that were treated operatively between December 2014 and November 2017. Demographic, fracture-related, and ophthalmic data were assessed and statistically analyzed. Results: This study included 282 patients. The most common fracture types were zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures and orbital floor fractures. Falls and violence were the most common causes of fractures (43.3% and 24.5%, respectively). Chemosis and subconjunctival bleeding were the most common associated eye injuries. The most prevalent long-term eye injury was diplopia, which was identified in 18.4% of cases preoperatively. Postoperative diplopia persisted in 36 cases (12.8%) at 3-month follow-up. Optic neuropathy, enophthalmos, exophthalmos, and retrobulbar hematomas were identified infrequently. Conclusion: Minor ophthalmic injuries, including chemosis and subconjunctival bleeding, are more frequently associated with midface trauma. These minor injuries tend to heal quickly and without sequela. Major ophthalmic injuries, including retinal detachment, optic neuropathy, and retrobulbar hematomas, are identified less frequently. Special attention should be paid to patients with diplopia, as this condition may persist and have long-term occupational consequences. Therefore, close interdisciplinary collaboration is essential when treating patients with fractures of the midface to prevent permanent visual impairment.

Introduction

Patients with fractures of the midface and the adjacent skeleton seldom experience associated major ophthalmic injuries. These patients are, however, much more likely to experience minor ophthalmic injuries, including subconjunctival bleeding and contusions of the eye bulb. The consequences of these injuries for patients can be drastic, especially when associated with loss of eyesight or permanent double vision. [1] The reported frequency of ophthalmic involvement in patients with fractures of the facial skeleton varies widely. [2,3,4] In some patients, immediate treatment of the ocular injury precedes the need for open reductions and internal fixations of the midface. Unfortunately, even with early surgical intervention for ophthalmic trauma, permanent visual impairment cannot be prevented in all cases. [5] Outcomes of surgical repairs of ophthalmic and skeletal injuries depend on several factors, including the expertise of the emergency response team, the type of impact, and the severity of the injury. A close collaboration among physicians from relevant disciplines, including ophthalmologists, on-call doctors, and maxillofacial surgeons, is also of vital importance in the management of these patients.

This study analyzed the frequency and distribution pattern of associated ophthalmic injuries in patients treated operatively for fractures of the midface in our oromaxillofacial clinic. The allocation and severity of the fractures were compared with the ophthalmic injuries. The effect of previous eye operations on the severity of ocular injuries associated with midface fractures was also investigated. Finally, long-term ophthalmic sequelae of surgically treated midface fractures were analyzed.

Material and methods

The clinical information system was searched to identify patients who underwent operative treatment for displaced fractures of the midface and the adjacent facial skeleton from December 2014 to November 2017. Information about demographics, type of skeletal injury, and type of ophthalmic involvement was gathered. All patients underwent a complete preoperative ophthalmological examination by an in-house ophthalmologist with assessment of pupillary light reflex, ocular motility, intraocular tension, eyesight, and presence of enophthalmos or exophthalmos. Primary outcomes were defined as the type of associated preoperative ophthalmic injury (chemosis, subconjunctival bleeding, diplopia, ocular contusion, impaired motility, anisocoria, eyelid injury, optic neuropathy, iris injury, exophthalmos, enophthalmos, retrobulbar hematoma, and retinal detachment) and fracture classification. Secondary outcomes included demographic and etiological data. Binocular diplopia, enophthalmos, and exophthalmos were also assessed postoperatively through 3-month follow-up. The correlation of ophthalmic injuries with any earlier eye operations was analyzed. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). The study fulfilled the criteria and was approved by the ethics committee of Zu¨rich (no. 2017-00210) and followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed a local general consent agreement.

Results

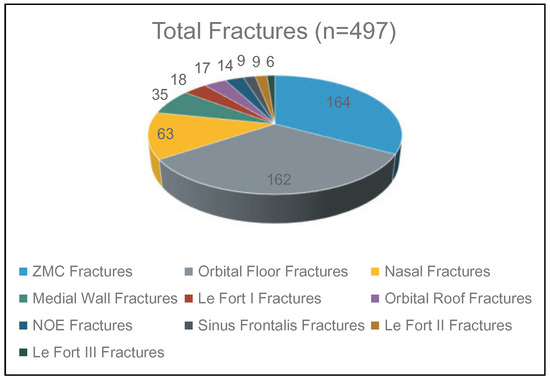

Two hundred eighty-two patients with a total of 497 fractures were included in this study. The mean age was 47.4 years (median: 45.9 years). Gender was predominately male (73.4%), with a female to male ratio of 1:2.8. The right side was affected in 133 cases (47.2%), the left side in 114 cases (40.4%), and both sides in 35 cases (12.4%).

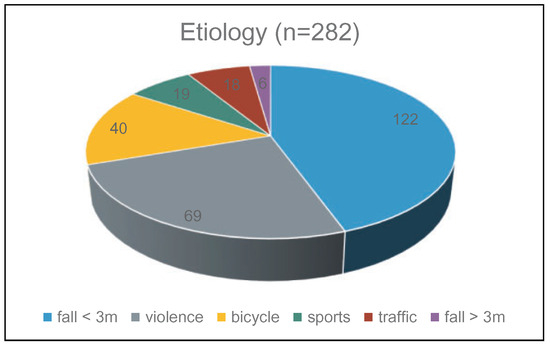

Falls were the most common cause of fractures, accounting for 122 cases (43.3%). Violence and bicycle accidents were the next most common causes, accounting for 24.5% and 14.2% of cases, respectively. All fracture etiologies are shown in Figure 1. When fracture types were analyzed by etiology, zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC) fractures and orbital floor fractures were most frequently involved (Figure 2). In these 2 categories, falls and violence outnumbered all other causes (43.3% and 24.5%, respectively). Interestingly, in cases with violence as an etiology, left-sided injury predominated (39 cases, 56.5%).

Figure 1.

Etiology of fractures.

Figure 2.

Analysis of fracture types. NOE indicates nasoorbitoethmoid; ZMC, zygomaticomaxillary complex.

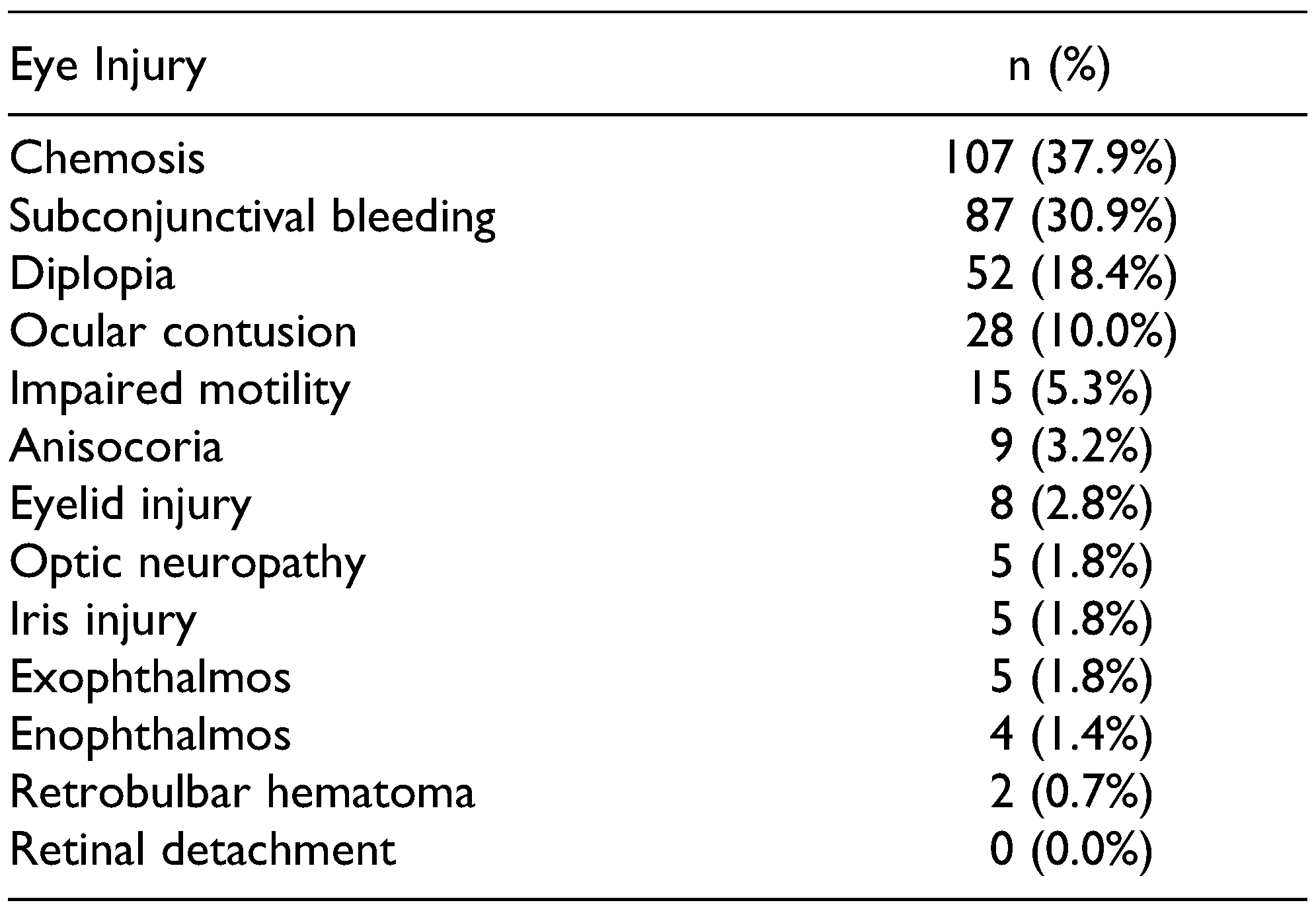

The most commonly reported concomitant eye injuries were chemosis and subconjunctival bleeding (37.9% and 30.9%, respectively; Table 1). No retinal detachment or eye bulb ruptures were reported. Of the 5 optic neuropathy cases, 4 cases had resolution at 3-month follow-up and 1 case remained impaired.

Table 1.

Analysis of Eye Injuries Associated With Fractures of the Midface.

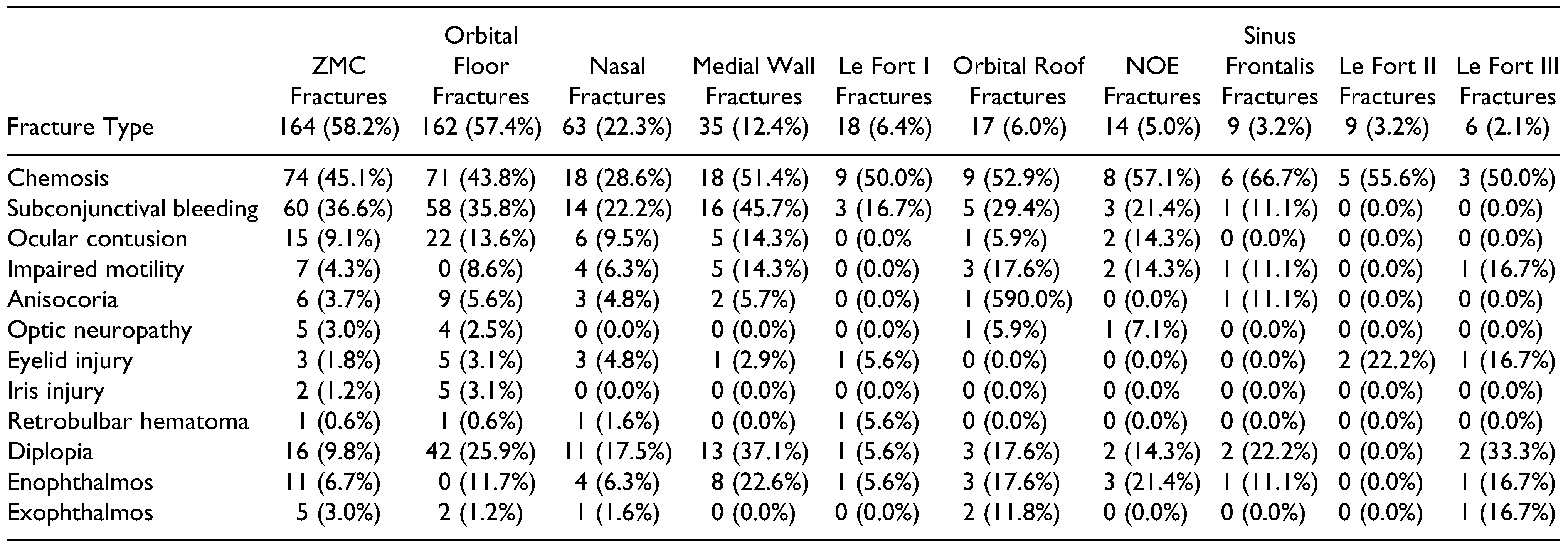

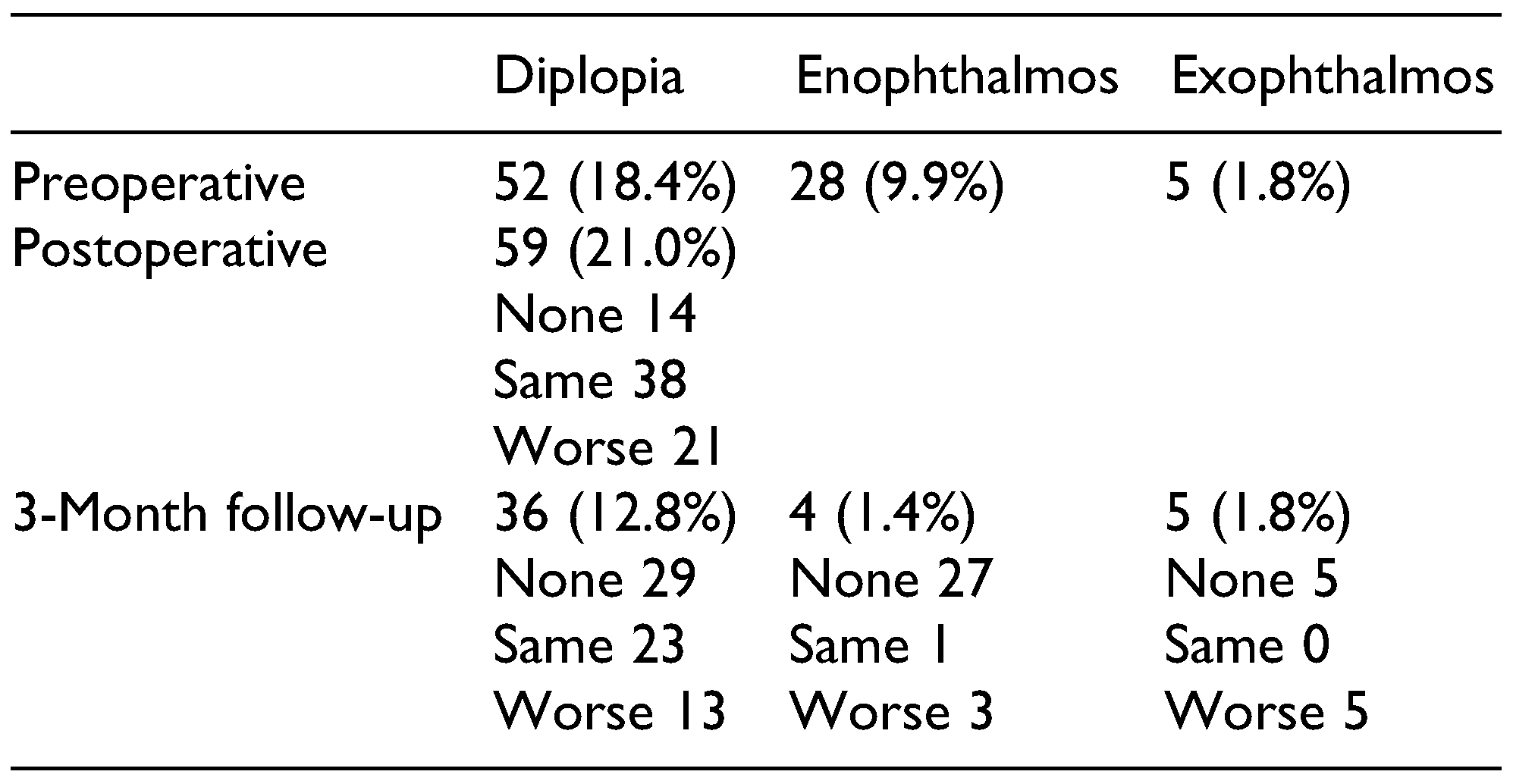

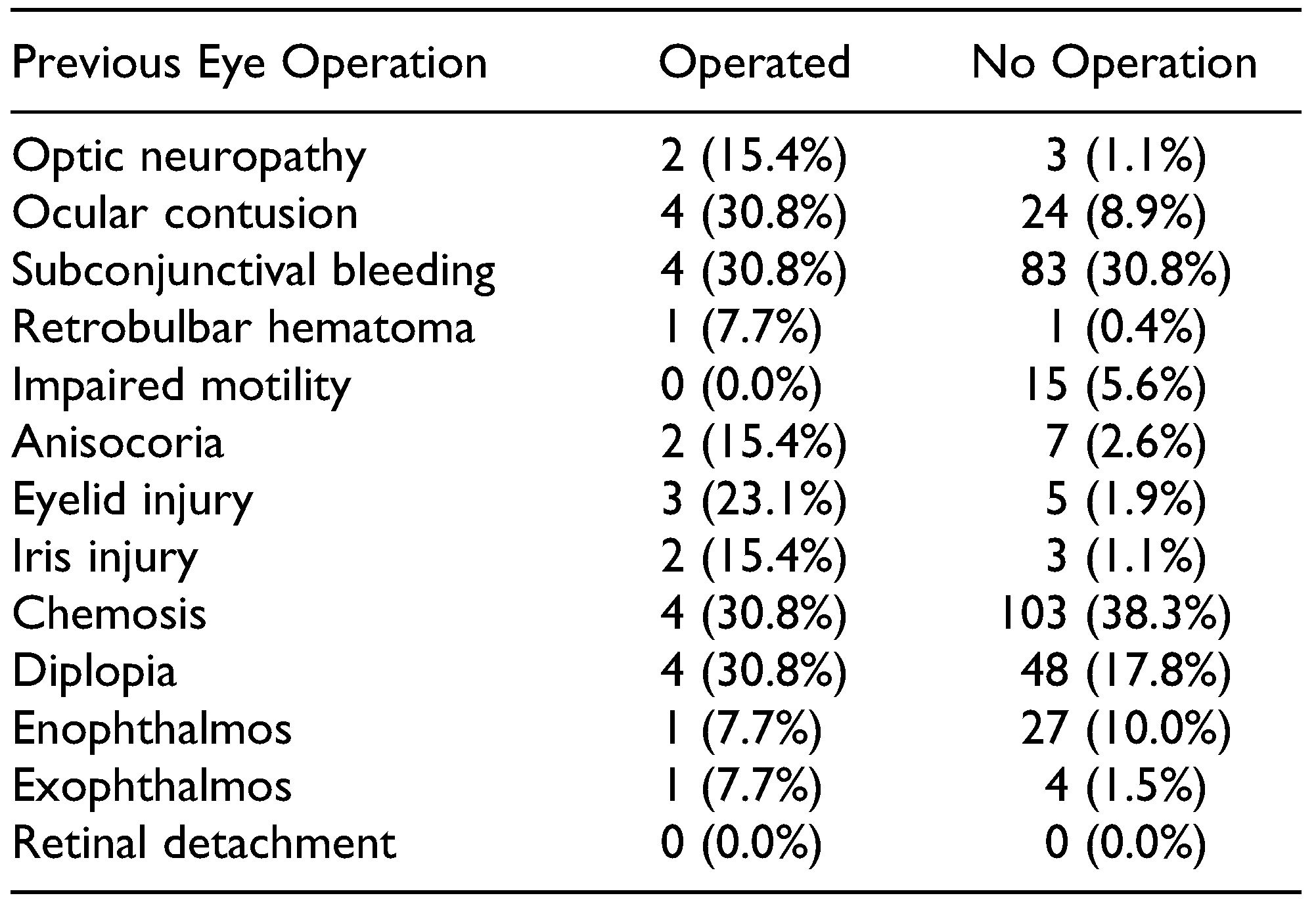

All concomitant eye injuries divided by fracture type are shown in Table 2. When analyzing fracture classification by the type of ophthalmic injury, binocular diplopia was very common. The highest prevalence was found in the medial wall (37.1%) and orbital floor (25.9%) fracture groups. Binocular diplopia was present preoperatively in 52 cases (18.4%). Diplopia also occurred in the immediate postoperative period). In 14 cases, diplopia resolved postoperatively, while new postoperative diplopia developed in 21 cases. Finally, at 3-month follow-up, diplopia occurred in 36 cases (12.8%). Diplopia was resolved completely in 29 cases (10.3%), new diplopia was diagnosed in 13 cases, and 23 cases of persistent diplopia were identified. Table 3 presents the results related to enophthalmos and exophthalmos at 3-month follow-up. All other associated ophthalmic injuries had resolved at 3-month follow-up. Also, some concomitant eye injuries seemed to be more common in patients who had undergone previous eye operations. Complete data are shown in Table 4.

Table 2.

Analysis of Associated Eye Injuries According to Fracture Type, n (%).

Table 3.

Analysis of Diplopia, Enophthalmos, and Exophthalmos Preoperatively, Immediately Postoperative, and at 3-Month Follow-Up.a

Table 4.

Frequency of Associated Eye Injuries in Patients With or Without Previous Eye Operations.a

Discussion

The frequency of ophthalmic involvement in patients suffering from fractures of the midface varies widely based on the discipline of reported data. [2,3,4] Furthermore, minor injuries are much more frequent than major injuries, which may explain the wide range of reported prevalence, due to exclusion of minor injuries from some studies.

In this study, the potential for recovery in patients suffering from mild ophthalmic injuries was excellent in comparison with previous findings. [1,6] The most commonly reported ophthalmic injuries were chemosis, subconjunctival bleeding, and binocular diplopia, all considered mild ophthalmic injuries, as reported in other studies. [7] On the other hand, major ophthalmic injuries were identified only seldomly, with optic neuropathy in only 5 cases (1.8%), retrobulbar hematomas in 2 cases (1.8%), and no retinal detachments or eye bulb ruptures.

No correlations were identified between these major injury types and fracture patterns. Retrobulbar hematomas occurred in 2 cases (one case with a combination of orbital, Le Fort, and nasal fractures and the other case with a combination of orbital and ZMC fractures). Optic neuropathy was identified in 5 cases, with a combination of ZMC and orbital fractures in all 5. In patients with midface fractures, the occurrence of these associated ophthalmic injuries must be considered and carefully excluded because related visual impairment (eg, diplopia) in people may have serious economic implications. [5] Depending on the level of visual field impairment and the type of occupation, these patients may have serious occupational consequences, with resultant impacts on social insurance. Therefore, a positive surgical outcome is fundamental in enabling these patients to return to work.

No monocular diplopia was identified in this patient group. Binocular diplopia was found in 52 patients preoperatively, most frequently in patients with orbital floor fractures but also in patients with ZMC and medial wall fractures. In 29 cases, diplopia resolved postoperatively, while 36 cases (12.8%) had long-term diplopia.

Fractures of the medial wall are often described to be asymptomatic, except for in cases with muscle incarceration. [8] In this study, 37.1% of patients with fractures of the medial wall had diplopia preoperatively. These patients also showed a high prevalence of chemosis (51.4%), subconjunctival bleeding (45.7%), and enophthalmos (22.6%). These findings may be explained by the combination of different midface fractures in these patients, as described in the literature. [9] Only 5 cases in this study had simple medial wall fractures, and none of these cases developed binocular diplopia pre- or postoperatively.

Young patients experienced the highest amount of violence and traffic accidents. [10] Road traffic accidents remain a significant contributor to major ophthalmic injuries, probably due to the high force of impact or deployment of airbags. [11] In our study, the most common causes of fracture were violence and falls under 3 m, which is consistent with a previous study related to ocular injuries among orbital fracture patients. [12]

Most eye injuries, including chemosis and subconjunctival bleeding, heal in a short time; however, others disappear after a longer time or never disappear, such as diplopia, enophthalmos, or exophthalmos. The most prevalent long-term eye injury in our study was binocular diplopia, which was found in 36 cases (12.8%) at 3-month follow-up. No rating was assessed (eg, central or degrees of peripheral visual field) to enable a more subtle estimation of impairments in daily living in these patients. An even higher prevalence of postoperative diplopia has been described previously. [13,14] Other long-term eye injuries, including enophthalmos or exophthalmos, were seldom identified.

In 13 cases, no preoperative binocular diplopia was identified, though persistent diplopia developed postoperatively. A complex midface fracture in combination with an orbital reconstruction was performed in 5 of these cases, a multiwall orbital reconstruction was performed in 3 of these cases, and in each 2 cases, an orbital floor and a complex midface fracture. These are all surgical interventions, which bear a high risk of diplopia sequelae.

Furthermore, all 36 patients with persistent binocular diplopia had the following fracture types: orbital multiwall (14 cases), medial wall (1), orbital floor (10), complex midface (3), or a combination of complex midface and orbital (8). Accordingly, diplopia seemed to correlate with more severe midface fractures.

Two cases (0.71%) of retrobulbar hematomas were reported in this study. In one case, immediate relief was obtained through an incision in all 4 quadrants. In the other case, the midface fracture was immediately repositioned. In both cases, vision was sustained, though diplopia persisted postoperatively and during follow-up.

Patients who have previously undergone an eye operation seemed to be more susceptible to eye injuries associated with midface fractures; however, the patient numbers in this study were too low to establish causality. The most common injuries, including chemosis and subconjunctival bleeding, seemed equally distributed in the operated and nonoperated group. On the contrary, optic neuropathy, bulbar contusions, retrobulbar hematomas, anisocoria, and iris injuries were more common in the operated group (Table 4), a finding which was also noted in an earlier study on eye injuries secondary to road traffic accidents. [6] This finding may have been biased by a potentially closer examination by ophthalmologists of patients with previous eye operations.

Of the eye-related cranial nerves, the optic nerve is the most frequently injured in association with midface fractures, although it was involved in only 5 cases (1.8%) in this study. Injuries of the optic nerve commonly carry a poor prognosis and contribute to related impairments in quality of life of patients. The following 3 types of trauma-related visual loss are described in the literature: immediate visual loss after trauma, delayed visual loss (eg, due to swelling), and postoperative visual loss after open reduction and internal fixation. [6,15] In our study, no patients with visual loss were identified. Neither treatment with corticosteroids nor optic canal decompression surgery has showed statistical significance in patients with traumatic optic neuropathy. One-third of all patients in an international study of traumatic optic neuropathy showed persistent visual impairment after trauma, as was the case in our sample (1 of 5 cases with optic neuropathy). [16] In 4 cases (of the 5), visual acuity was recovered, although in 2 cases, other associated injuries (diplopia) remained.

Although several studies related to ophthalmic injuries can be identified in international databases, comparison of these studies remains difficult due to lack of definitions. [17] Major eye injuries are seldom associated with midface fractures but still have to be ruled out. If a clinical suspicion exists (ie, change in visual acuity or intubated patients), a referral to an ophthalmologist should be placed immediately. [12,18] In all other cases, an ophthalmologist examination should be carried out at some point for medicolegal reasons, since a quarter of these injuries is due to interpersonal violence. This recommendation is supported by previous studies on orbital fractures and associated injuries. [12,19]

A known drawback of this study is its retrospective nature. Nevertheless, the authors believe that the high number of included patients outweighs this fact.

In our sample, the majority of ophthalmic injuries were minor, compared with the findings of previous studies. Minor ophthalmic injuries showed high potential for spontaneous recovery. Nevertheless, major injuries did occur and must be taken into consideration during emergency assessments.

Conclusion

Minor ophthalmic injuries, including chemosis and subconjunctival bleeding, are the most common ocular injuries associated with midface trauma. These minor injuries often heal quickly and without sequelae. Clinicians should pay special attention to diplopia, as it may persist and even force occupational changes in patients. Major ophthalmic injuries, including retinal detachment, optic neuropathy, and retrobulbar hematomas, occur less frequently. These major ocular injuries seem to occur more frequently in complex midface and orbital fractures and in patients with previous eye operations. In these cases, an ophthalmologist should be consulted to prevent permanent visual impairment. It is imperative to perform timely and skilled treatment of patients with major ophthalmic injuries associated with midface fractures, and prevention of these injuries is also of the highest priority.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Jamal, B.T.; Pfahler, S.M.; Lane, K.A.; et al. Ophthalmic injuries in patients with zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures requiring surgical repair. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009, 67, 986–989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- al-Qurainy, I.A.; Stassen, L.F.; Dutton, G.N.; Moos, K.F.; el-Attar, A. The characteristics of midfacial fractures and the association with ocular injury: A prospective study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991, 29, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lim, L.H.; Lam, L.K.; Moore, M.H.; Trott, J.A.; David, D.J. Associated injuries in facial fractures: Review of 839 patients. Br J Plast Surg. 1993, 46, 635–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez Marin, I.; Traspas Tejero, R.; Fernández Dominguez, M.; Mencía Gutiérrez, E. Ocular injuries in midfacial fractures. Orbit. 1998, 17, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Amrith, S.; Saw, S.M.; Lim, T.C.; Lee, T.K.Y. Ophthalmic involvement in cranio-facial trauma. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2000, 28, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guly, C.; Guly, H.; Bouamra, O.; Gray, R.H.; Lecky, F.E. Ocular injuries in patients with major trauma. Emerg Med J. 2006, 23, 915–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, S.G.; Kotwal, I.A.; Joshi, U.; Allurkar, S.; Thakur, N.; Aftab, A. Ophthalmological evaluation by a maxillofacial surgeon and an ophthalmologist in assessing the damage to the orbital contents in midfacial fractures: A prospective study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2016, 15, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brannan, P.A.; Kersten, R.C.; Kulwin, D.R. Isolated medial orbital wall fractures with medial rectus muscle incarceration. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006, 22, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ordon, A.J.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Wilczynski, M.; Loba, P. The influence of concomitant medial wall fracture on the results of orbital floor reconstruction. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018, 46, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassner, R.; Tuli, T.; Hächl, O.; Rudisch, A.; Ulmer, H. Craniomaxillofacial trauma: A 10 year review of 9543 cases with 21067 injuries. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003, 31, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duma, S.M.; Kress, T.A.; Porta, D.J.; et al. Airbag-induced eye injuries: A report of 25 cases. J Trauma. 1996, 41, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ross, M.; El-Haddad, C.; Deschenes, J. Ocular injury in orbital fractures at a level I trauma center. Can J Ophthalmol. 2017, 52, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gavin Clavero, M.A.; Simón Sanz, M.V.; Til, A.M.; Jariod Ferrer, Ú.M. Factors influencing postsurgical diplopia in orbital floor fractures and prevalence of other complications in a series of cases. J Oral and Maxillofac Surg. 2018, 76, 1725–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoli, D.; Fadda, M.T.; Battisti, A.; et al. Retrospective analysis of 301 patients with orbital floor fracture. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015, 43, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, M.H. Blindness after facial fractures: A 19-year retrospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005, 63, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Levin, L.A.; Beck, R.W.; Joseph, M.P.; Seiff, S.; Kraker, R. The treatment of traumatic optic neuropathy: The International Optic Nerve Trauma Study. Ophthalmology. 1999, 106, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Magarakis, M.; Mundinger, G.S.; Kelamis, J.A.; Dorafshar, A.H.; Bojovic, B.; Rodriguez, E.D. Ocular injury, visual impairment, and blindness associated with facial fractures: A systematic literature review. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2012, 129, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellema, P.A.; Dewan, M.A.; Lee, M.S.; Smith, S.D.; Harrison, A.R. Incidence of ocular injury in visually asymptomatic orbital fractures. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009, 25, 306–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andrews, B.T.; Jackson, A.S.; Nazir, N.; et al. Orbit fractures: Identifying patient factors indicating high risk for ocular and periocular injury. Laryngoscope. 2016, 126 (suppl 4), S5–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the author. The Author(s) 2020.