Abstract

Background and Overview: Gunpowder inclusion injuries are rare occurrences in the civilian sector but are more frequently encountered in the military setting. The authors report a case series of 3 active duty military service members treated by an Army hospital’s Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery service for the removal of embedded gunpowder particles so as to avoid traumatic tattooing. Case Description: Three otherwise healthy active duty military service members were treated for gunpowder inclusion injuries incurred while conducting live fire training exercises at a state-side military installation between 2018 and 2019. All 3 males presented with injuries of the same etiology: Their weapons malfunctioned, and while visually inspecting the action, a round exploded close to the face. This peppered the face with gunpowder particles that were both superficially and deeply embedded. Treatment focused on individual removal using fine forceps. The patients were followed up and healed quickly without any complications, specifically without traumatic tattooing from the gunpowder injuries. Conclusion and Practical Implications: Gunpowder inclusion injuries should be addressed quickly to remove the particles before epidermal healing occurs, thus avoiding the complication of traumatic tattooing. This surgical team recommends meticulous fine forceps removal as the treatment of choice for larger particles.

Case Series

The following depicts 3 cases treated between 2018 and 2019 at an Army Hospital in the United States. The first case was a 24-year-old male, otherwise healthy with an unremarkable medical history who reported to the emer- gency department at a US Army military facility with the chief complaint that during clearance of a jam of his machine gun (also known as a SAW or Squad Automatic Weapon designation M249 utilizing 5.56-mm ammuni- tion), a round exploded in his face (Figure 1). The patient reported he had removed his eye protection (ballistic glasses) to check the status of the weapon malfunction when the round exploded. The patient was worked up fully by the emergency department, including radiological eva- luation for larger and deeper pieces of metallic debris, which was negative. While in the emergency room, medics removed brass shrapnel and aggressively scrubbed the face with normal saline. After cleansing the wounds, the patient still had over 50 subcutaneous retained gunpowder pellets. The Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery was consulted for further treatment, along with the Department of Ophthalmology to evaluate and treat his minor eye injuries.

Figure 1.

Twenty-four-hour evaluation of case 1.

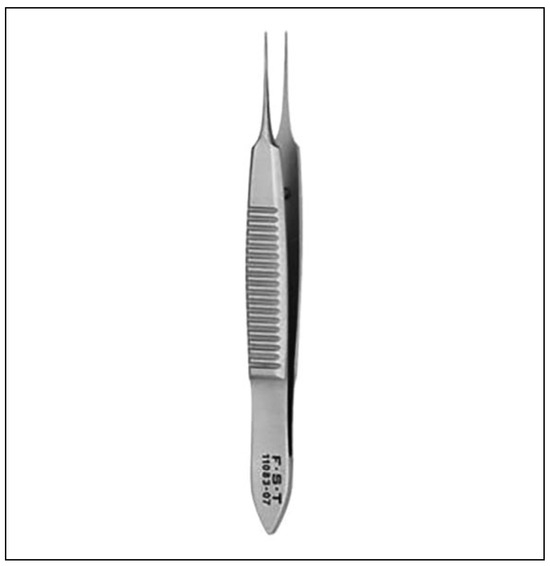

A series of photographs detailing the gunpowder pellets were obtained. Due to the concern for future tattooing of the skin with retained gunpowder, the decision was made to remove the pellets under intravenous (IV) sedation. The IV sedation was initiated per institution protocols. Once the patient was sedated, his face was prepped with ChloraPrep (Chlorhexidine Gluconate). To ensure that no pellets were missed, the surgeon addressed the face in quadrants. A 0.5-mm forcep, a small forcep commonly used in plastic surgery, was used to gently elevate the superficial epider- mal tissue overlying the gun powder pellets. At this time, manual pressure applied laterally caused the pellets to erupt to the surface where they were removed. This approach was successful for larger, superficial pellets. The pellets that were not removed with this technique were then removed easily using the 0.5-mm forceps (Figure 2) to gently enlarge the opening at the site of entry and grasp the gun- powder pellets and remove them. Although a time- consuming technique, by focusing on each quadrant of the face methodically, complete removal of gunpowder inclu- sions was achieved. The face was then cleansed using nor- mal saline, and bacitracin applied to the wounds. The patient was discharged with close clinic follow-up.

Figure 2.

The 0.5-mm Bonn Micro forceps.

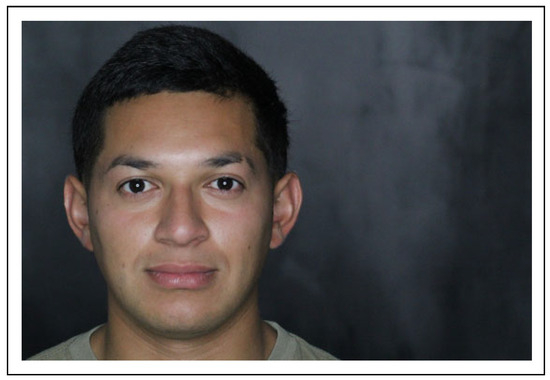

The patient returned for a 2-week follow-up and denied any pain or issues. Patient was very happy with the appear- ance of his face (Figure 3). Clinically, the patient showed no signs of tattooing from gunpowder pellets. He has small areas of erythema at sites where larger shrapnel and gun- powder had been embedded, but minimal to no scarring was evident.

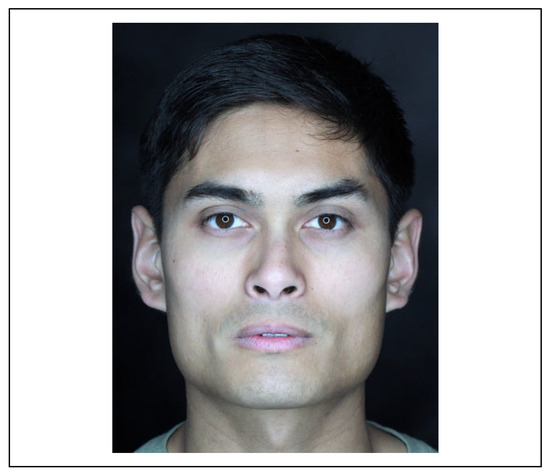

Figure 3.

Fourteen-day postoperative photo of case 1.

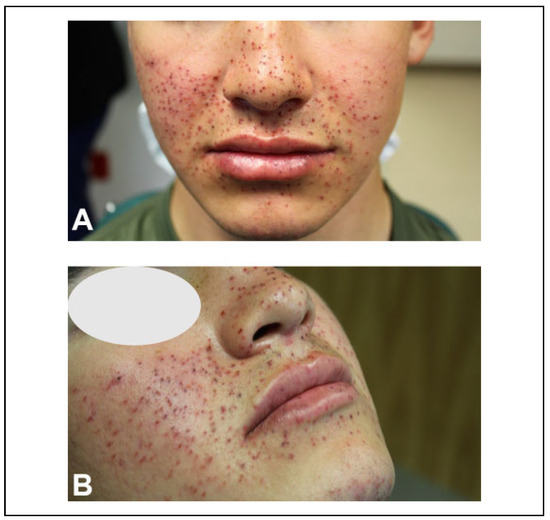

The second case parallels the first. A 19-year-old male, otherwise healthy with an unremarkable medical history, reported to the same emergency department. An active duty Marine, he was at the Army base conducting joint training operations. During operations with his SAW, he reported a round detonated in his face while trying to clear it after a jam. He was wearing ballistic eye protection at the time, as one can ascertain from the injury pattern (Figure 4A and B).

Figure 4.

(A and B) Eight-hour evaluation of case 2.

Similar to the first case, the patient was worked up fully and then sedated and the gunpowder fragments removed in a manner similar to that described earlier. Gentle pressure and manipulation with fine forceps resulted in the removal of all fragments (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Immediate postoperative photos after gun powder removal.

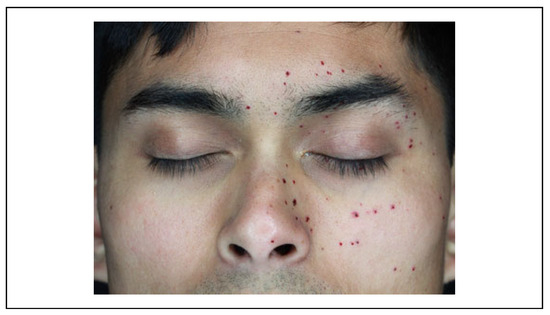

The third case involved an otherwise healthy 25-year- old special forces solider. During live fire maneuver train- ing, the solider was manning an M249 SAW, the same weapon system as in the abovementioned cases, when a round jammed. The soldier opened the breach and saw a round was jammed and leaned back and away to grab a tool to help remove the jam, at which point the round detonated. Although the patient was wearing eye protection, several small fragments impacted underneath and into the lower eyelid, without any damage to the globe (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Initial evaluation pretreatment.

After evaluation and workup, a ChloraPrep surgical scrub was used to debride the injury and remove superficial gunpowder particles (Figure 7). As mentioned earlier, a fine forcep was used to remove all fragments (Figure 8) with the immediate postoperative result shown (Figure 9) and 2 week postoperative results shown (Figure 10).

Figure 7.

Chlorhexidine surgical scrub used to debride injury.

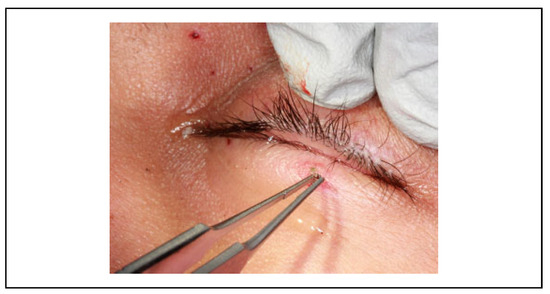

Figure 8.

Fine forceps removal of gunpowder pellet.

Figure 9.

Immediate post removal of gunpowder inclusions.

Figure 10.

Two-week postoperative photo.

Discussion

Traumatic tattoo injuries resulting in gunpowder inclusions are commonly seen in blast or ballistic injuries as well as in firework injuries. In a war-zone environment, it is a com- mon injury. In a state-side military setting, they are often seen in training accidents. The most common etiology of these injuries and what caused the abovementioned patients to present to the emergency department is as follows: When a ballistic cartridge is struck by the firing pin, a malfunction occurs if the gunpowder does not immediately ignite. If the weapon overheats, as can be caused by automatic firing, the heat of the barrel can cause a delayed ignition of the gun- powder. This becomes problematic when the operator opens the action of the weapon to visually inspect the mal- function. When the bullet or round explodes or “cooks off” as it is commonly known as, it is often due to residual heat in the area or a delay in internal mechanisms of the round. The round detonates in an unpredictable pattern with the force normally sending a projectile out of the barrel, instead out of the breach. These injuries become most concerning if the operator removes their ballistic eyewear to closely visually inspect the weapon at the time the round cooks off. If left untreated, these injuries can result in traumatic tat- tooing of skin tissues, which is of particular concern on the face and neck.

Within what is commonly thought of as a bullet resides gunpowder and a primer to help set it off. Upon ignition from chemical, physical, or electrical stimulus, the primer initiates the combustion that forces the projectile from the barrel of the gun. Most small arm weapons, like rifles and hand guns, function through a series of events, wherein the firing pin strikes the cartridge, initiating a chemical reaction. Historically, common chemicals used to fulfill this function include mixtures of compounds containing sulfur, fulminate, potassium chlorate, and now more recently, most primers use lead styphnate and lead azide. Gunpowder’s themselves are extremely varied and often proprietarily protected, though most contain nitrocellulose. Upon weapon discharge, some gunpowder travels out of the barrel unignited or par- tially ignited (typically not more than 48 inches).[1,2] This partially or unignited gunpowder means that it will, gener- ally speaking and depending of the myriad of manufactures variations, be a material that when struck with and energized by a laser will set off an exothermic reaction.

A current literature review revealed numerous treatment options for the removal of the particulate matter that has been traumatically tattooed, and more specifically, gun- powder. The following will review these options in the context of both a wartime, deployed environment and a state-side hospital environment. Most importantly, there is no perfect answer to treat these injuries, and a provider must use their clinical judgment about when to use each technique and when to ask for help.

Consensus treatment is to start by aggressively scrub- bing using sponges, surgical scrub brushes, and/or wire brushes.[3,4] This should be done ideally within 6 hours but as soon as 72 hours; once the skin has healed, the ability to remove the particulate with scrubbing is lost.[5] Using wire brushes in this fashion can be effective but can be traumatic itself and require a prolonged healing period as well as potentially leaving debris behind. The authors prefer to start with chlorhexidine surgical scrub brushes to remove as much particulate as possible and do not routinely use a wire brush technique for the reasons outlined earlier. An important note is that chlorhexidine can pose a serious risk to the eyes and ears, with reports of ocular keratitis and even permanent vision loss.[6] It should be carefully applied with these considerations in mind.

The authors’ therapy of choice is particle identification and meticulous removal with fine forceps using surgical loupes with magnification to treat larger particles that are able to be identified. This may take several procedures over the course of several days if the injury warrants. The authors’ experience has shown that the removal of gunpow- der pellet inclusions using 0.5-mm or 0.25-mm forceps, although somewhat tedious and taking between 1 and 2 hours per treatment, is an excellent treatment adjunct. The procedure is comfortable for the patient, provides a cos- metic end result with no facial tattooing, has a short recov- ery period, and is easily performed in both the deployed setting and a state-side hospital.

Also described are the use of liquid-assisted devices for cleaning and irrigating. The use of hydrosurgery to assist via a Versajet system has been successfully used but is dependent upon the availability of the system and compo- nent parts, which could be restrictive in a deployed envi- ronment.[7] More in-depth surgical techniques have been described such as microsurgical dermabrasion: Simply put, after primarily healing, the patient will undergo another procedure, wherein the area of traumatic tattoo is incised in a grid pattern and small squares of the dermis removed in a splint thickness technique with the area allowed to gran- ulate in.[8,9] There are other methods of dermabrasion and microsurgical removal described, but most are secondary surgical techniques and primarily the purview of experi- enced plastic surgeons.[10] These techniques would likely be limited to a state-side environment.

A point to highlight is that treatment of gunpowder inju- ries varies with respect to lasers. Lasers are a common way to treat other types of traumatic tattoos but are contraindi- cated as treatment of gunpowder inclusion injuries. Laser therapy with a multitude of types have been described, including CO2, diode, erbium, and neodymium yttrium alu- minum garnet (Nd: YAG), though the most prolific for treatment of tattoos, be it traumatic or otherwise, seems to be the Nd: YAG Q switched laser. Although a deep discussion of laser physics is beyond the scope of this arti- cle, briefly the Nd: YAG laser produces light at the wave- length of 1064 nm which is strongly absorbed by black- and dark-colored pigments. The wavelength can also be halved through a filter to 532 nm which has an intense affinity for lighter colors such as orange, red, and pink. Q-switching means the laser produces a very intense, but very brief, pulse, strong enough to shatter the aforementioned pig- ments upon absorption but leaving the normal tissue archi- tecture unharmed.[11,12,13,14]

The laser can provoke sparks, ignite gunpowder, and result in the immediate formation of bleeding transepider- mal pits causing a more disfiguring injury. Studies have shown that this produces pox-like scars and the spreading of pigments in the skin around the initial points of the tattoo, thus worsening the aesthetic effects of the pig- ment.[15,16] There have been a number of studies published examining these issues along with the complication of igni- tion and further damage.[17]

One advantage of the fine forceps technique over a laser technique (if one is considering traumatic tattoo from a non- gunpowder source) is the applicability to all skin types. Fitzpatrick skin type’s I-III, and possibly IV, can be treated with laser therapy, but types V and VI are not amendable to laser therapy with the potential for disfiguring hypopigmen- tation. This represents a small case series of these injuries, and due to the limited nature no direct comparisons can be made, and the authors recommend further research into this area. Unfortunately, the authors do not have longer term follow-up photos due to the transient nature of the military.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ Note

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, Depart- ment of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Bruner, D.; Gustafson, C.G.; Visintainer, C. Ballistic injuries in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract. 2011, 13, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ogunniyi, A.; Wu, A. Forensic emergency medicine. In Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice; Walls, R.M., Hockberger, S.R., Gausche-Hill, M., et al., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, 2018; pp. e1–e21, chap e1. [Google Scholar]

- Bohler, K.; Muller, E.; Huber-Spitzy, V.; et al. Treatment of traumatic tattoos with various sterile brushes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992, 26, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hohenleutner, U.; Landthaler, M. Effective delayed brush treat- ment of an extensive traumatic tattoo. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000, 105, 1897–1899. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reid, M. Facial trauma: soft tissue injuries. In Plastic Surgery Volume 3: Craniofacial, Head and Neck Surgery and Pediatric Plastic Surgery; Rodriguez, E.D., Losee, J.E., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 22–46, chap 2. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, M.M.; Cox, D.O.; Smith, C.V.; Onouye, T.; Moy, R.L. Ocular damage due to chlorhexidine versus eye shield ther- mal injury. Dermatol Surg. 2001, 27, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siemers, F.; Stang, F.H.; Namdar, T.; Senyaman, O.; Maila¨nder, P. Removal of accidental inclusion following blast injury by use of a hydrosurgery system (VersajetTM). Injury Extra. 2010, 41, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, M.; Isshiki, N.; Taira, T.; Matsumoto, A. The use of microsurgical planing to treat traumatic tattoos. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994, 94, 1069–1072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Guan, W. Treating traumatic tattoo by micro-incision. Chin Med J. 2000, 113, 670–671. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peris, Z. Removal of traumatic and decorative tattoos by der- mabrasion. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2002, 10, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kirby, W.; Desai, A.; Kartono, F. Tattoo removal techniques: effective tattoo removal treatments—Part I. Skin and Aging. 2005, 9, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, S.M. Current concepts in laser tattoo removal. Skin Therapy Lett. 2010, 15, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.N.; Bae, E.Y.; Park, J.G.; Lim, S.H. Permanent makeup removal using Q-switched Nd: YAG laser. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009, 34, e594–e596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, R. Tattoo removal. In A Practical Guide to Cosmetic Lasers; Small, R., Ed.; Lippincott: Philadelphia, PA, 2012; pp. 367–376, chap 4. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C.R. Laser ignition of traumatically embedded fire- work debris. Lasers Surg Med. 1998, 22, 157–158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ashinoff, R.; Geronemus, R.G. Rapid response of traumatic and medical tattoos to treatment with the Q-switched ruby laser. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993, 91, 841–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusade, T.; Toubel, G.; Grognard, C.; Mazer, J.M. Treatment of gunpowder traumatic tattoo by Q-switched Nd: YAG laser: an unusual adverse effect. Dermatol Surg. 2000, 26, 1057–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2020 by the author. The Author(s) 2020.