Salvage Secondary Reconstruction of the Mandible with Vascularized Fibula Flap

Abstract

Aims and Objectives

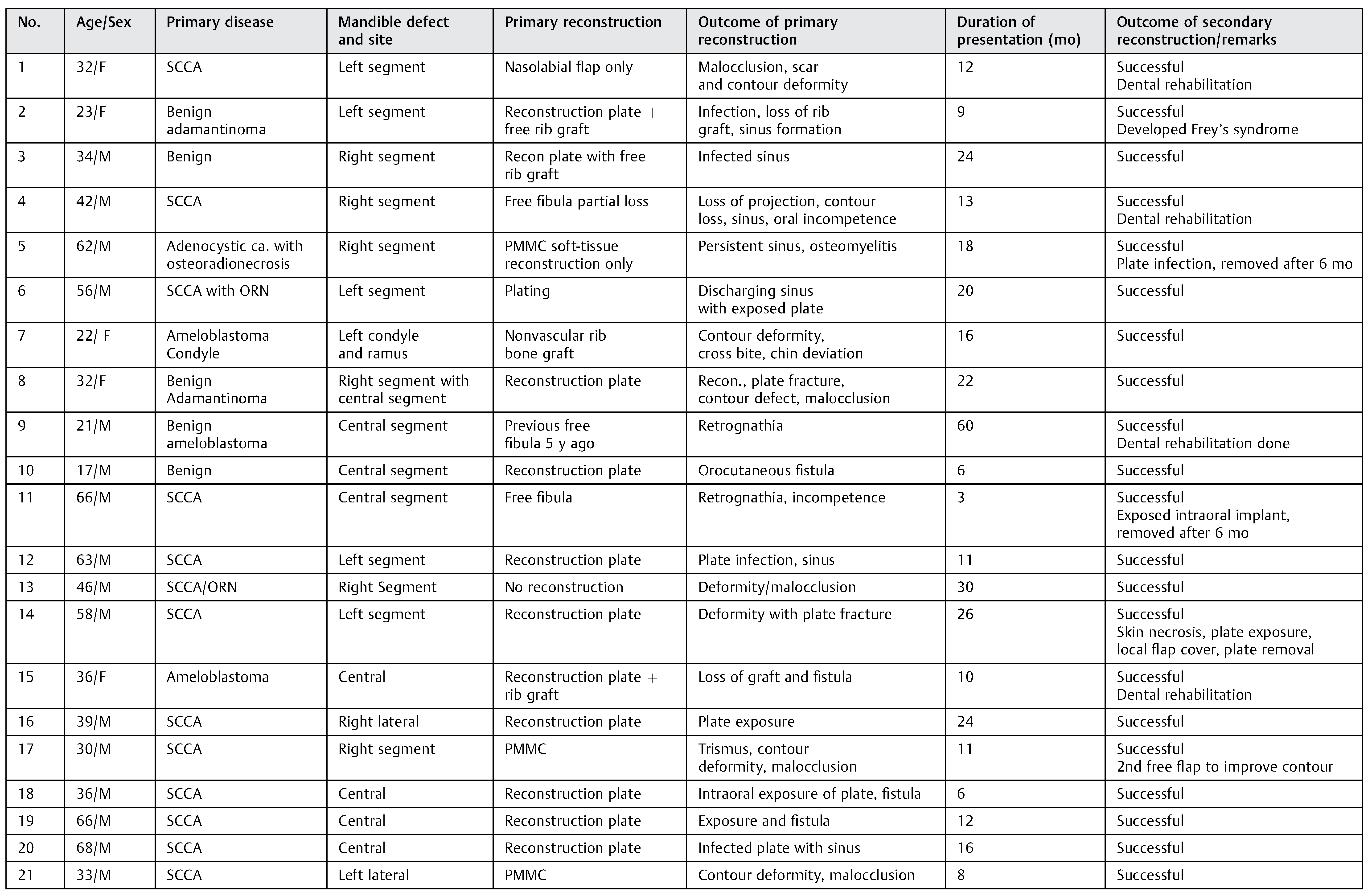

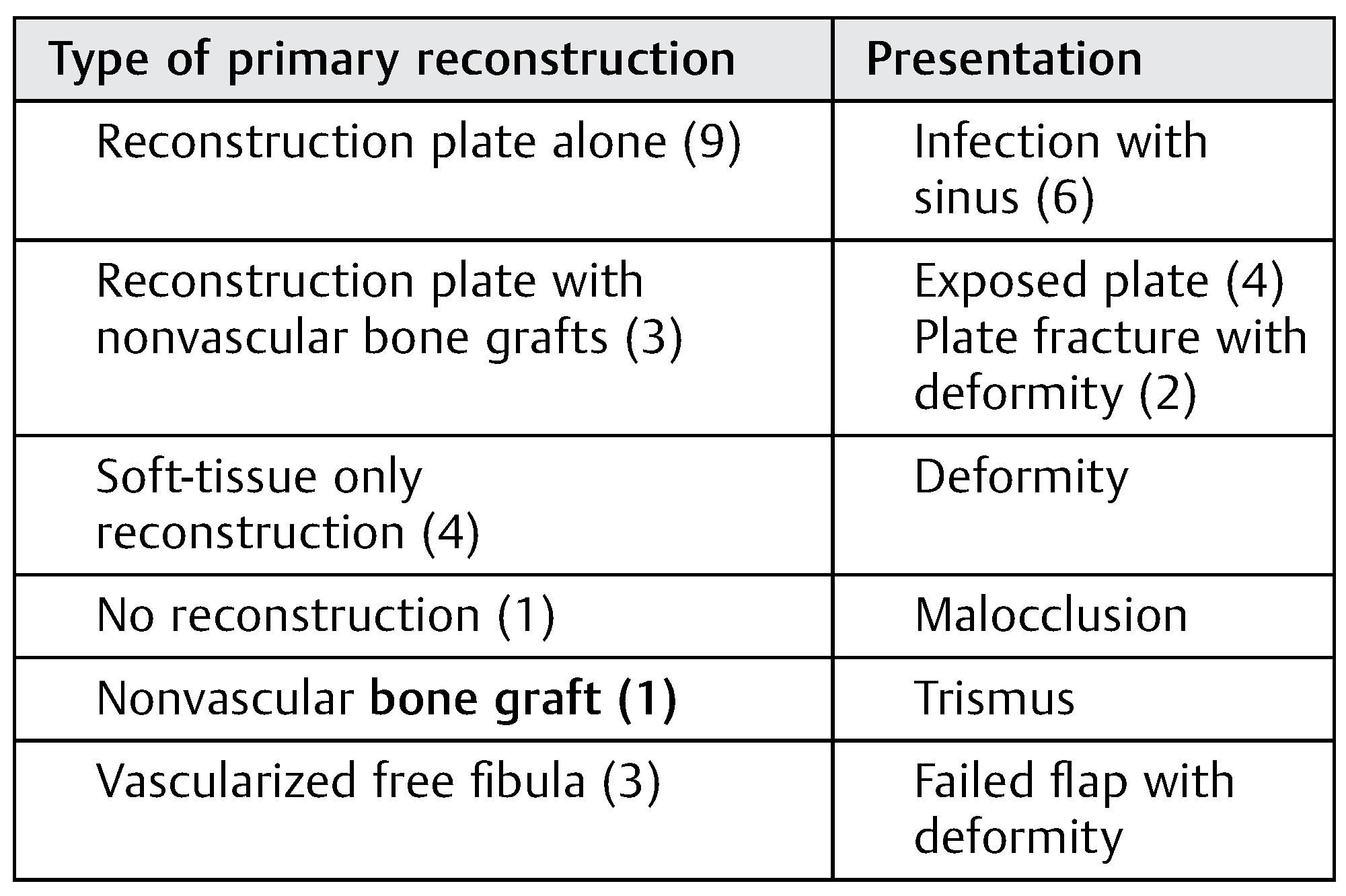

Patients and Methods

Results

Illustrations of Cases

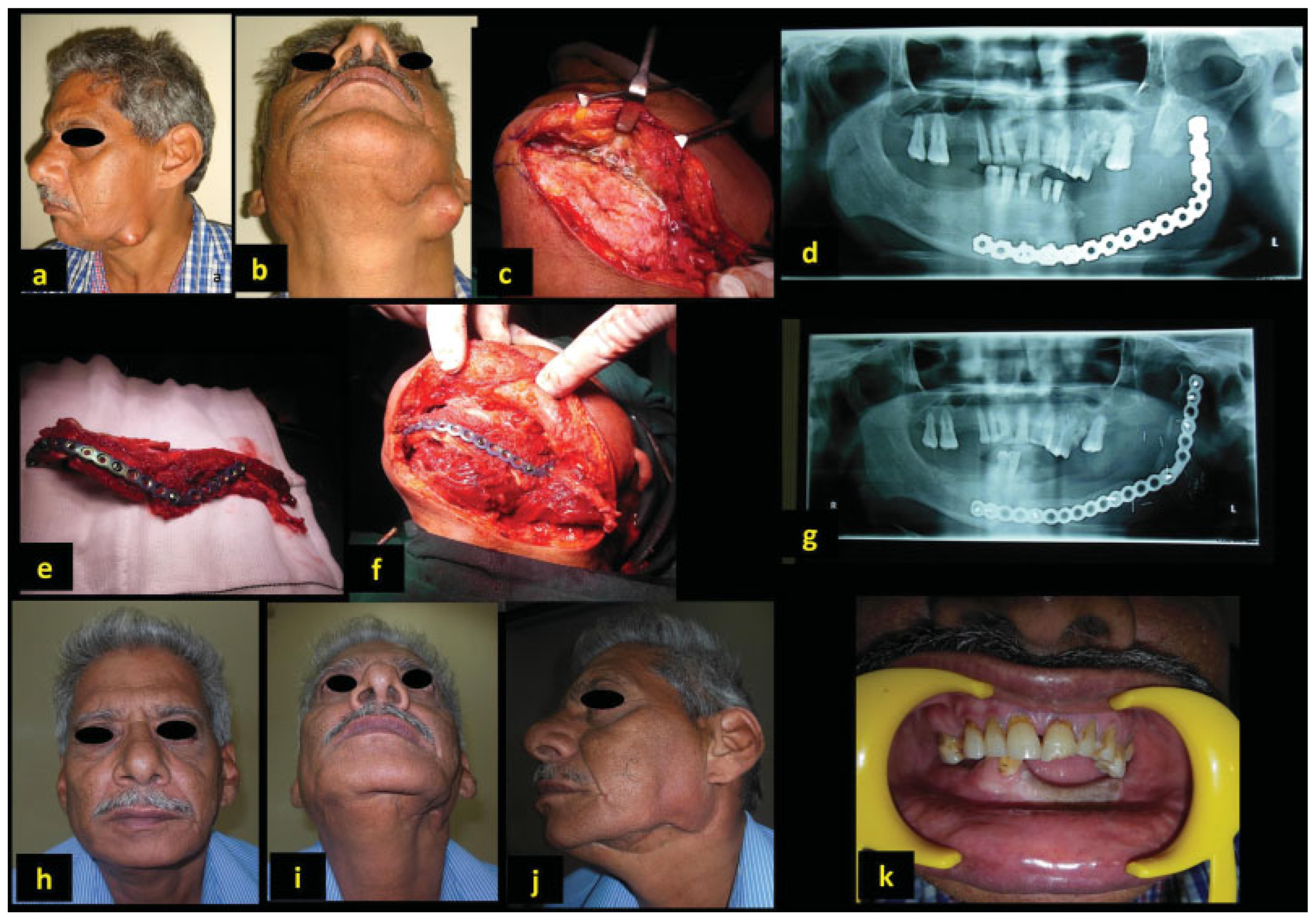

Case 1

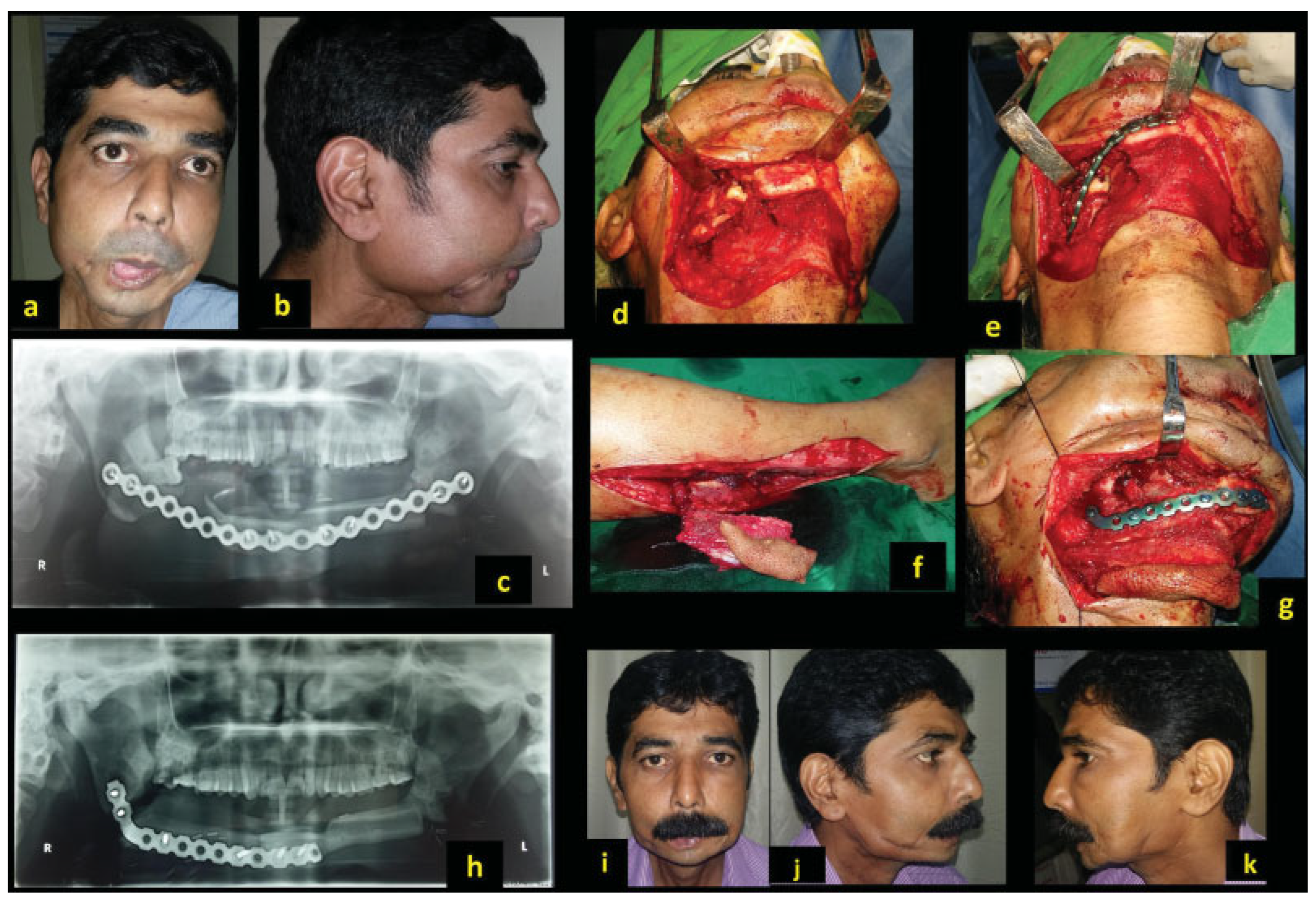

Case 2

Case 3

Case 4

Case 5

Discussion

- Recreating the primary defect: Definitive reconstruction with osseous free flaps is ideal, but there is reluctance, and not always preferred when it comes to secondary reconstruction. [8] During primary reconstruction, a clear measurable defect is created by the ablative surgeon. The burden of recreating the defects in secondary surgery rests with the reconstructive surgeon. This is not only a daunting task but often beyond their tailored skills and comfort levels even for an accomplished surgeon. Obtaining a true defect may not be possible owing to extensive tissue contractions. Failure to recreate original 3D defects itself could be deterrent to choose appropriate reconstruction.

- Extensive fibrosis and loss of tissue plane: This is particularly encountered following radical neck dissection with further external radiation therapy. Following neck dissection and removal of investing neck fascia, the vessels are directly under the skin flap with thin atrophied platysma intervening between skin and vessels. Dissection in this plane potentially results in injury to thin-walled veins. Further, radiation causes hypovascularity and induces fibrosis which is visible as dense, thin, and pale tissue planes.

- Finding suitable recipient vessels is a paramount task and should be the first step of the procedure without committing to the defect. Frequently during the neck dissection for the primary disease, the tributaries of the internal jugular veins (IJVs) are either not preserved or the vein itself is removed. In the absence of both internal and external jugular vein, we explored the contralateral neck. Should that becomes necessary, the orientation of the flap is kept such a way that the exit end of pedicle is nearest to the recipient vessels in the contralateral neck. The choice of recipient artery is also limited. The facial artery is often ligated and thrombosed. However, we find adequate length of the artery is available deep under the digastric muscle. This is accessed by dividing the digastric tendon and lifting the muscle to uncover the vessel. The available vessel length is generally healthy, well preserved, and protected under the digastric muscle from previous surgery and radiation. The other reliable vessel is the superior thyroid artery. The venous anastomosis could be end to end to the IJV tributary or end to side to IJV. We prefer to explore and dissect recipient vessels as a first step before proceeding, as often the contralateral neck is utilized. In this series, five patients underwent anastomosis in the contralateral neck. Digital mapping of good caliber vessels is possible [9] and reliability of patency needs to be ascertained.

- The soft-tissue release required is often much more than the anticipated volume to achieve adequate mouth opening and occlusion. The defect thus created is larger, needing inclusion of good amount of soft tissue with the fibula. Typically, the defects include floor of mouth following release of lingually shifted mandible. The intraoral defect often includes cheek, gingivo-buccal sulcus, and the floor of mouth. Extraorally, though the closure is achieved in most cases, additional skin may be needed to close incisions in the neck or chin. Reconstruction of these 3D defects needs careful planning. Large skin paddle either single or bipaddle preserving perforators is necessary. Additionally, flexor halluces longus muscle is useful in obliterating the floor defects and in augmenting soft-tissue loss to improvise contour around the mandible.

- The bony defect is often collapsed in the absence of reconstruction plate. The recreated defect and true bony gap is measured after keeping the mandible in occlusion. Importantly, it should be remembered that the true bony gap is calculated only after freshening the edges of the bone ends. Irregular ends are slivered with a saw for a smooth bleeding end. It may be necessary to resect old fixation points to get an adequate purchase for the new screw fixation.

- Absence of condyle further complicates the reconstruction and fixation. If the glenoid fossa is well surrounded by the soft tissue, the upper end (ramus) of reconstructed mandible can occupy the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) space. For this, the width of the upper end of the vertical limb of contoured fibula requires narrowing to match the size of the condyle. This is kept projected at least 15 mm beyond the edge of the plate to resemble the condyle (Figure 6a–d). This creates a pseudo joint which moves along with the contralateral TMJ. If there is instability to maintain the bony end in the glenoid fossa, the end of the bone is anchored to the soft tissue with nonabsorbable suture or rarely using stainless steel wire as suspension to the zygoma. It is important to limit the extent of plate much below the bony ends so that potential erosion into the glenoid fossa is avoided and removal of the plate, if necessary, is easier.

- Reestablishing the precise contour of the mandible is a difficult task. The following are used for shaping the mandible: the previous plate, precontoured guiding plate, CT-guided 3D digital printing technology, and stereolithographic models.9,10 In our patients, it was either previous plate or precontoured reconstruction plate based on the subjective assessment of the contralateral side while keeping the remaining jaw in occlusion. However, it is recommended to use objective means for accurate contouring whenever possible. The soft-tissue requirement and additional bone loss with freshening should be kept in mind during preoperative planning.

- The skin of the neck generally is tougher and less pliable owing to contraction and fibrosis. Further redraping the additional volume of reconstructed mandible is difficult. This possibly results in a secondary defect which may require an additional skin paddle of the flap and skin grafting or may be left open for secondary healing or delayed suturing. Elevation of large poorly vascularized skin flaps is prone for devascularization and necrosis, particularly with tight closure. The most distal part of elevated lip-split incision is chin and remains vulnerable for necrosis.

- Finally, as per our preference, neck skin closure is done with just few tacking sutures, avoiding compression on the pedicle and leaving 1- to 2-cm gap between sutures for adequate drainage. Since airtight closure is not done, no closed suction drain is utilized, instead a sterile absorbent pad is kept on the wound and changed frequently when soaked. Unlike in primary neck dissection, the potential space available for any fluid collection is extremely limited, and slightest collection under nonpliable skin causes pressure which is detrimental to the anastomosis. In addition, large hematoma can potentially compress the neck and upper airway due to pressure under closed space.

- The measure of success in secondary reconstruction is limited to the flap survival and amelioration of the presenting problems. Though the goals of achieving near-perfect function and cosmesis remain as in the primary reconstruction, realistic approach is needed considering several limitations listed earlier. Despite technical difficulties to carry out microsurgical reconstruction, [8] the overall success of flap survival is similar to the primary reconstruction in our study. We encourage such an attempt, as good outcome can be anticipated by paying attention to several factors discussed above. However, it should also be kept in mind that failure of salvage reconstruction can be disastrous and life threatening for a patient who was “managing” without reconstruction, and should such situation is faced, a second salvage plan be kept as a “lifeboat.”

Conclusion

Funding

Note

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hayden, R.E.; Mullin, D.P.; Patel, A.K. Reconstruction of the segmental mandibular defect: Current state of the art. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012, 20, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferretti, C.; Rikhotso, E.; Muthray, E.; Reyneke, J. Interim reconstruction and space maintenance of mandibular continuity defects preceding definitive osseous reconstruction. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013, 51, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Freitag, V.; Hell, B.; Fischer, H. Experience with AO reconstruction plates after partial mandibular resection involving its continuity. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1991, 19, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibahara, T.; Noma, H.; Furuya, Y.; Takaki, R. Fracture of mandibular reconstruction plates used after tumor resection. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002, 60, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iseli, T.A.; Yelverton, J.C.; Iseli, C.E.; Carroll, W.R.; Magnuson, J.S.; Rosenthal, E.L. Functional outcomes following secondary free flap reconstruction of the head and neck. Laryngoscope 2009, 119, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, T.Y.; Strub, G.M.; Yawn, R.J.; Day, T.A. Oromandibular reconstruction. Clin Anat 2012, 25, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Straub, J.M.; New, J.; Hamilton, C.D.; Lominska, C.; Shnayder, Y.; Thomas, S.M. Radiation-induced fibrosis: Mechanisms and implications for therapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2015, 141, 1985–1994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andrade, W.N.; Lipa, J.E.; Novak, C.B.; et al. Comparison of reconstructive procedures in primary versus secondary mandibular reconstruction. Head Neck 2008, 30, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, W.B.; Liu, X.J.; Guo, C.B.; Yu, G.Y.; Peng, X. A new procedure assisted by digital techniques for secondary mandibular reconstruction with free fibula flap. J Craniofac Surg 2016, 27, 2009–2014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ciocca, L.; Mazzoni, S.; Fantini, M.; Persiani, F.; Marchetti, C.; Scotti, R. CAD/CAM guided secondary mandibular reconstruction of a discontinuity defect after ablative cancer surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2012, 40, e511–e515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

|

|

|

© 2019 by the author. The Author(s) 2019.

Share and Cite

Kadam, D. Salvage Secondary Reconstruction of the Mandible with Vascularized Fibula Flap. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2019, 12, 274-283. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1685460

Kadam D. Salvage Secondary Reconstruction of the Mandible with Vascularized Fibula Flap. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2019; 12(4):274-283. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1685460

Chicago/Turabian StyleKadam, Dinesh. 2019. "Salvage Secondary Reconstruction of the Mandible with Vascularized Fibula Flap" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 12, no. 4: 274-283. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1685460

APA StyleKadam, D. (2019). Salvage Secondary Reconstruction of the Mandible with Vascularized Fibula Flap. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 12(4), 274-283. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1685460