Severe trauma cases, osteoradionecrosis, and head and neck cancer can cause extensive defects of the oral and maxillofacial region. Facial defects can be categorized as either softtissue defects or as composite defects, in which bone and soft tissue are both needed. The need for reconstruction of these defects has led to the development of multiple tissue-transfer techniques. For composite defects, the free vascularized fibula flap (FFF) has been the primary choice of many reconstructive surgeons since Taylor et al[

1] described its harvest and Hidalgo[

2] advocated for its use in mandibular reconstruction. It offers multiple advantages: the availability of ample bone length, the possibility of performing osteotomies for anatomical shaping, a versatile soft tissue unit with the option of multiple skin paddles, long vascular pedicles with an adequate diameter of the vessels, bicortical bone stock for dental implant placement, and the use of a two-team approach, reducing operating time.[

3,

4,

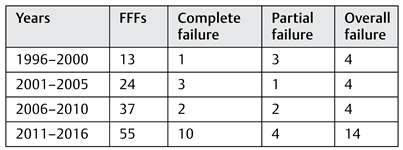

5] Overall success rates of free flap surgery are reported to be over 95%,[

6] and recent studies on free fibula flaps reported overall success rates of 90 and 93%.[

7,

8] However, a subset of FFFs do fail, mostly because of arterial or venous thrombosis. In addition, complications after FFF surgery arise often, in the donor site as well as in the acceptor site. These complications are frequently underreported and are difficult to compare among studies.

Discussion

The FFF has been one of the workhorses of oral and maxillofacial reconstruction, especially in mandibular defects. The ample bone length, long vascular pedicle, and promise of less donor-site morbidity compared with an iliac crest flap[

11] have made it the preferable free vascularized flap in mandibular reconstruction. Also, because of its septocutaneous perforators and its periosteal blood supply, the FFF can be osteotomized and shaped to fit the anatomy of the defect that needs reconstruction.

The success rate of 79.8% found here is lower than other reports, probably because of the use of strict criteria to define failure and success: if a FFF was taken with a skin paddle and the skin paddle did not survive, this event was classified as a partial failure. If these salvaged flaps had been included in the success rate, a success rate of 87.6% would have been obtained, which is still slightly lower than other reports.[

3,

8,

12] Four flap failures occurred more than 30 days after initial surgery. Two of them presented with initial loss of the skin paddle which eventually progressed to total flap failure. The third flap had to be removed due to recurrent malignant disease affecting the free flap 1 year after reconstruction. The remaining failure was a patient who had a FFF for reconstruction of the temporomandibular joint due to severe ankylosis. During the first postoperative months, the patient developed refractory pain at the reconstructed joint as well as severe trismus for which the flap was eventually removed. Also, follow-up of flaps was done by residents, both junior and senior, which may cause a delay in flap revision. Vascular crisis and venous thrombosis in particular formed the main reason for flap failure. Venous crisis has been reported as the main reason for salvage procedures[

6,

13,

14] and can be regarded as the most fragile vascular component of the pedicle. The venous anastomosis is susceptible to spasms, compression by hematoma or edema, and kinking by postoperative head and neck flexion or extension.[

14] This leads to venous congestion and eventually venous thrombosis. Although careful postoperative monitoring of these risk factors is standardly performed, some flaps could not be salvaged in time. To improve vascular outcome for the transferred tissue, an adequate preoperative evaluation of vascular structures should be performed. Computed tomography (CT) angiography of the lower limbs is the standard when a FFF is planned, with a dual goal: detecting and evaluating peripheral vascular disease and evaluating anatomical anomalies of the lower limb vasculature. Critical infra-popliteal vascular anomalies are found in 10% of the population and 5.2% of limbs, meaning that if the peroneal artery were to be sacrificed, the result could be ischemic complications of the donor site.[

15] Also, the CT data can be used with virtual-planning software in preparation for the procedure.[

16,

17]

Furthermore, ischemia time should be limited to a maximum of 5 hours.[

18] This threshold has proven to be a critical point at which flap failure rates increase. This is due to hypoxia of the transferred tissue, which causes cellular and vascular damage that can lead to total partial flap loss.[

18] Virtual planning and the use of digital surgical guides can help the surgeon to reduce ischemia time.[

16,

17] This study did not include ischemia time in the analysis for risk factors of flap failure. This was due to incoherent or absent reporting in the operating reports of this parameter. Finally, close and rigorous postoperative monitoring is key to obtaining good results. If circulation problems do arise and flow cannot be re-established within 8 to 12 hours, the flap has a high chance of failing.[

19] Early detection of vascular problems is therefore essential. Bedside clinical monitoring is mostly used by evaluating color, capillary refill, turgor, temperature, and pinprick testing with the addition of Doppler surface monitoring, although the superiority of this method has not yet been confirmed.[

20] Other techniques such as implantable venous Doppler probes and contrast-enhanced Doppler are promising but have yet to be confirmed as superior and currently seem less practical.[

20] Close monitoring is essential in the first 5 days, the period when a vascular crisis tends to occur.[

13]

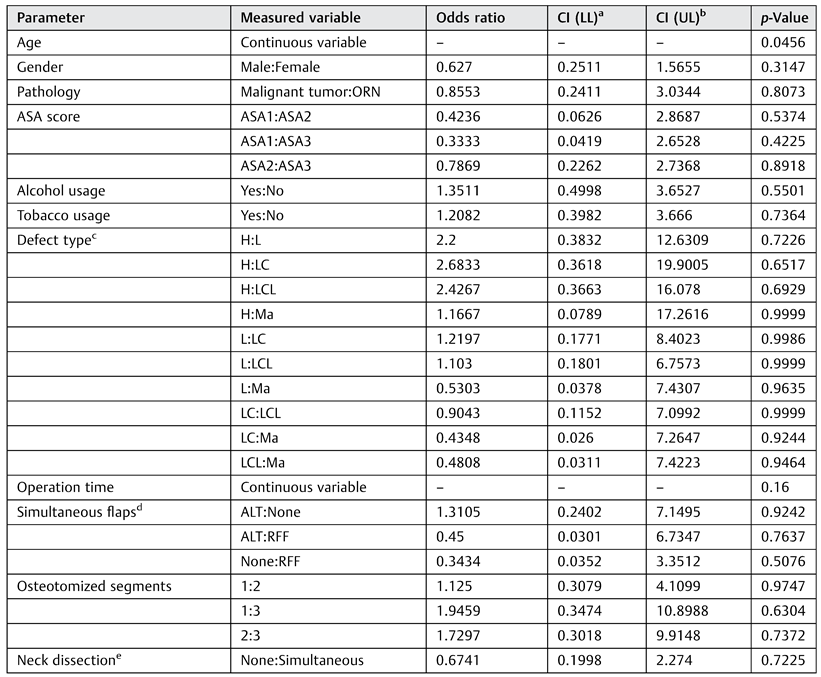

This study found a statistically significant relationship between younger age and a higher rate of flap failure. The statistical analysis identified a significant relationship but no cutoff value. A total of 65% of patients with a total or partial failure of the FFF were 55 years old or younger. Failure occurred early as well as late postoperatively in this group. A significant relation between younger age and flap failure was identified, but the authors could not provide an evidence-based explanation for this phenomenon. Some reports mention a debatable higher risk of excessive vasospasm in a pediatric population.[

21,

22,

23] However, previous studies investigating risk factors for flap loss did not identify younger or older age as a risk factor.[

9,

12] As the included number of patients in this study is low, this finding should therefore be interpreted with caution and should be further studied in larger study groups.

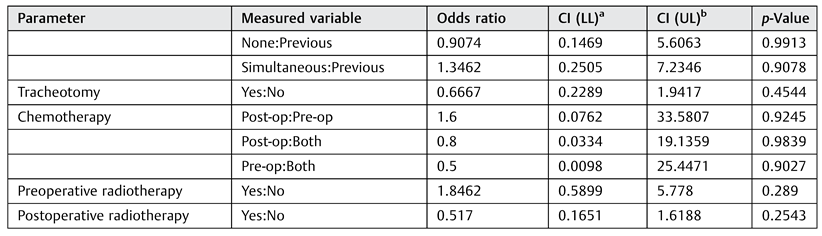

No other statistically significant risk factors were identified. Perioperative radiotherapy was not found to be a risk factor for flap failure, in agreement with other reports.[

9,

24,

25,

26] Chemotherapy also was not identified as a risk factor for flap failure, in contrast to the results of Chang et al,[

9] who found an increased flap failure risk with chemotherapy. Higher failure rates in reconstructed defects that included the condyle (H- HC) were noted, although this finding was not statistically significant. In our opinion, this trend could be attributed to the vascular pedicle being more prone to kinking due to its position when reconstructing defects extend to the condyle. Obtaining a tension-free anastomosis with adequate space for the vascular pedicle and providing clear postoperative posture instructions are keys in these cases.

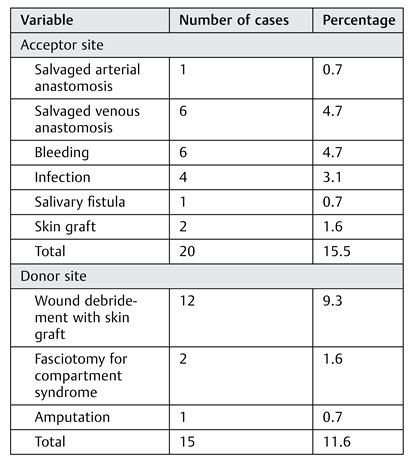

Although failure rates are important, they give only a limited view of the total patient experienced with FFF. Complications are difficult to compare between studies because definitions vary. The present study included every reported complication as defined earlier, yielding a complete overview of all adverse events following FFF reconstruction. Using broad inclusion criteria for complications produced higher numbers of postoperative complications than otherwise found in literature. However, identifying these pitfalls leads to a more complete informed consent as well as an opportunity for optimizing the procedure and perioperative care.

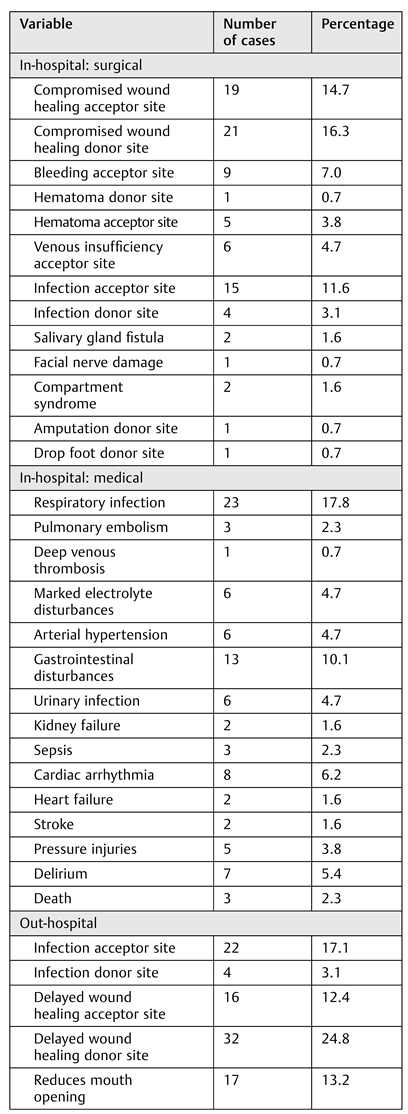

Delayed wound healing at the acceptor site (14.7%) and the donor site (16.3%) was the most reported surgical inhospital complication, followed by infection of the acceptor site (11.6%). When reconstructing oral defects, a higher risk of infection from the nonsterile environment should be countered with prophylactic antibiotics and adequate flap design. One patient developed an acute arterial crisis of the donor site with ischemic pain refractory to endovascular procedures, which eventually led to amputation of the lower limb. This patient was preoperatively evaluated only with duplex sonography, which showed no anomalies. Today, a CT angiography is always performed to identify vascular anomalies, as recommended.[

15]

In-hospital medical complications should not be underestimated because they can cause considerable morbidity and even mortality. Every patient received low-molecular- weight heparin in a prophylactic dose after a FFF procedure. However, three patients still developed a pulmonary embolism, and two patients had a stroke. Three patients died during admission, two with unexplained sudden cardiac death and one who developed anaphylactic shock caused by vancomycin, given for an extensive infection of the donor site. Cardiac arrhythmia occurred in eight patients, mostly atrial fibrillation. Given the extent of the procedure and the often-fragile patient population, close monitoring during admission and a proper antithrombotic regime using low- molecular-weight heparin in prophylactic dosing is advocated. Delirium occurred in seven patients; this condition can pose a challenge during the first days postoperatively because adequate posture for preventing traction and kinking of the vascular pedicle is key in this period. Delirium should be actively screened for, and rapid intervention is desirable if it occurs. Finally, a relatively high rate of respiratory infections (17.8%) was noted in this study. Given the post hoc finding of a statistically significant association of tracheostomy and respiratory infection, careful clinical evaluation and decannulation as soon as possible should be the goal if tracheostomy is performed.

The number of out-of-hospital complications was high (77.5%), and donor-site morbidity played an important role in this category. Li et al[

27] also identified late donor-site morbidity as a frequent postoperative problem using the FFF. Delayed donor-site wound healing occurred in 24.8% of all patients. More important, 17.1% of patients reported a neuromuscular deficit of the donor site, ranging from ankle instability to pain or cramps and paresthesia of the calf. A recent study of Feuvrier et al[

28] showed that patients who had had a FFF procedure walked more slowly and had a slower cadence and shorter stride length than control subjects more than 2 years after the procedure. Sieg and colleagues[

29] performed a long-term evaluation of donor-site morbidity in FFFs and described a small group of patients with serious donor-site morbidity that led to use of walking aids or persistent sensory or motor deficits. Although the FFF is advocated as being associated with less donor-site morbidity than the iliac crest free flap,[

11] some reports claim the opposite.[

30] Donor-site morbidity should therefore not be underestimated, and adequate informed consent and postoperative physiotherapy should be provided.[

28]

A reduced mouth opening (13.2%) and difficulties with swallowing (11.6%) and speech (6.2%) are also underreported postoperative complications that pose a challenge for postoperative rehabilitation. In 6.2% of patients, marked neurological complaints of the acceptor site were present, including neuropathic pain in the operated region, extensive paresthesia, and absent taste sensation. Although some patients with long-term follow-up showed signs of calcification of the vascular pedicle, no interventions for ossification of the vascular pedicle as described by Autelitano et al[

31] were needed.

The FFF procedure still has a high number of postoperative complications resulting in high morbidity for patients in spite of adequate preoperative planning, optimized operative techniques, adequate postoperative care, and close follow-up. This high number of registered postoperative complications should be read in the light of the definition that was used in this study. This study opted to define complication broadly as any unwanted result of the surgery that compromised healing or function as perceived by the patient. An argument could be made that some reported functional complications are inherently bound to this type of surgery (e.g., temporomandibular joint complaints or swallowing difficulties). However, these types of complications are not mentioned by every patient or recorded by the attending physician during follow-up which renders their “inherent character” questionable. Individual perception of complications by patients seems to play an important role in how patients handle postoperative sequelae.

This study reported on failure rates, risk factors, and postoperative complications of the FFF in oral and maxillo- facial reconstruction in a low-volume setting. The presented results differ from other reports.[

6,

9] This can be attributed to several factors. First, strict definitions were set for complete and partial failure. Second, the study opted for a broad view on complications. Finally, these are the results of a low- volume center. An argument can be made that a higher number of procedures lead to better survival rates and a lower complication rate due to more experience and more standardized way of care. However, these results provide a better understanding of the limitations of the FFF in a low- volume center and can be used to optimize care in this kind of setting. The retrospective design is an obvious weakness of the study. Not all data were reported in a standardized way, and some data could not be retrieved. Also, the power of the study was low because the group consisted of only 129 patients. A higher number of patients could have resulted in the detection of other risk factors. The finding that younger age was associated with higher risk of flap failure should therefore be interpreted with caution. In spite of a standardized policy, minor interpersonal differences could have led to different outcomes. Observer and reporter bias in the registration of complications, especially for the out-of- hospital group, could not be avoided given the retrospective design, long study period, and multiple senior surgeons and residents in a residency training program performing the procedures and providing follow-up. On the other hand, the fact that all patients at the University Hospitals of Leuven have had a unique electronic medical patient file since 2007 leaves little room for loss of data for hospitalized patients.