Contemporary septorhinoplasty and nasal reconstruction techniques emphasize grafting to maintain long-term function and structural integrity. Autologous cartilage is an ideal graft material with certain advantages including availability, biocompatibility, and ease of use.[

1] The ear and rib are common sources of autologous cartilage in patients whose septal cartilage is depleted or insufficient for grafting.

When a large quantity of strong grafting material is needed for nasal reconstruction, rib cartilage is an attractive and versatile option.[

2] The primary advantage of rib cartilage is its abundance and intrinsic strength. Limitations include both warping and calcification, which interferes with carving and suturing. One disadvantage of harvesting rib cartilage is pneumothorax, with the complication rate noted to be less than 1%.[

3] Another frequently cited disadvantage is increased postoperative donor site pain, though there is a paucity of literature to support this claim.

Auricular cartilage is also frequently used for grafting in septorhinoplasty and nasal reconstruction. It is harvested from the helical root, rim, conchal bowl, or tragal regions depending on the nature and location of the nasal defect.[

4] Advantages of auricular cartilage include a donor site that is proximal to the nose and ease of harvest through either anterior or posterior approach. The intrinsic elasticity and curvature of the ear are limitations to the utility of ear cartilage. Other disadvantages include the potential for permanently altering the ear contour. Moreover, patients commonly report significant donor site discomfort that exceeds the pain in their nose. On the other hand, many surgeons believe that pain caused by ear cartilage harvest is less than the pain associated with rib cartilage harvest. Nevertheless, there is no evidential support for these observations in the existing literature.

No previous investigations have quantified or compared postoperative auricular and rib donor site morbidity nor examined patients’ perception of postoperative ear deformity following cartilage harvest. The purpose of our study was to prospectively assess costal and auricular cartilage donor site morbidity in patients undergoing nasal surgery. We specifically sought to compare donor site pain between rib versus ear cartilage graft patients with nose pain within each group. We hypothesized that morbidity at both ear and rib cartilage donor sites was minimal.

Materials and Methods

We performed a pilot study that consisted of 55 consecutive eligible patients who underwent nasal surgery requiring costal or auricular cartilage performed by two facial plastic surgeons at the University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC) from February 2015 to May 2016. Inclusion criteria consisted of patients who underwent septorhinoplasty, nasal valve repair, and/or nasal reconstruction requiring auricular or costal cartilage grafting. All patients provided informed consent with willingness to comply with the study protocol and attend all study visits. Only patients who were unable to read and write fluently in English were excluded. This study was approved by the University of Kansas Human Subjects Committee.

At the time of nasal surgery, costal and auricular cartilage grafts were harvested via standard techniques. Rib cartilage was obtained by each surgeon from either the fifth or sixth rib through an inframammary or infrapectoral incision on female and male patients, respectively. The wound was closed with sutures in layered fashion. For ear cartilage grafts, both surgeons performed complete harvest of the floor of the cymba cavum and cymba conchae, regardless of approach. The ear donor site was closed primarily, with a bolster dressing placed to prevent hematoma formation.

Each participating patient provided written consent in the clinic at their first follow-up visit. Patients were issued a symptom-specific patient survey that was completed at their postoperative clinic visits at 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months after surgery. This survey consisted of pain scales and the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale, the only standardized tool to date designed for evaluation of scars by both professionals and patients.[

5]

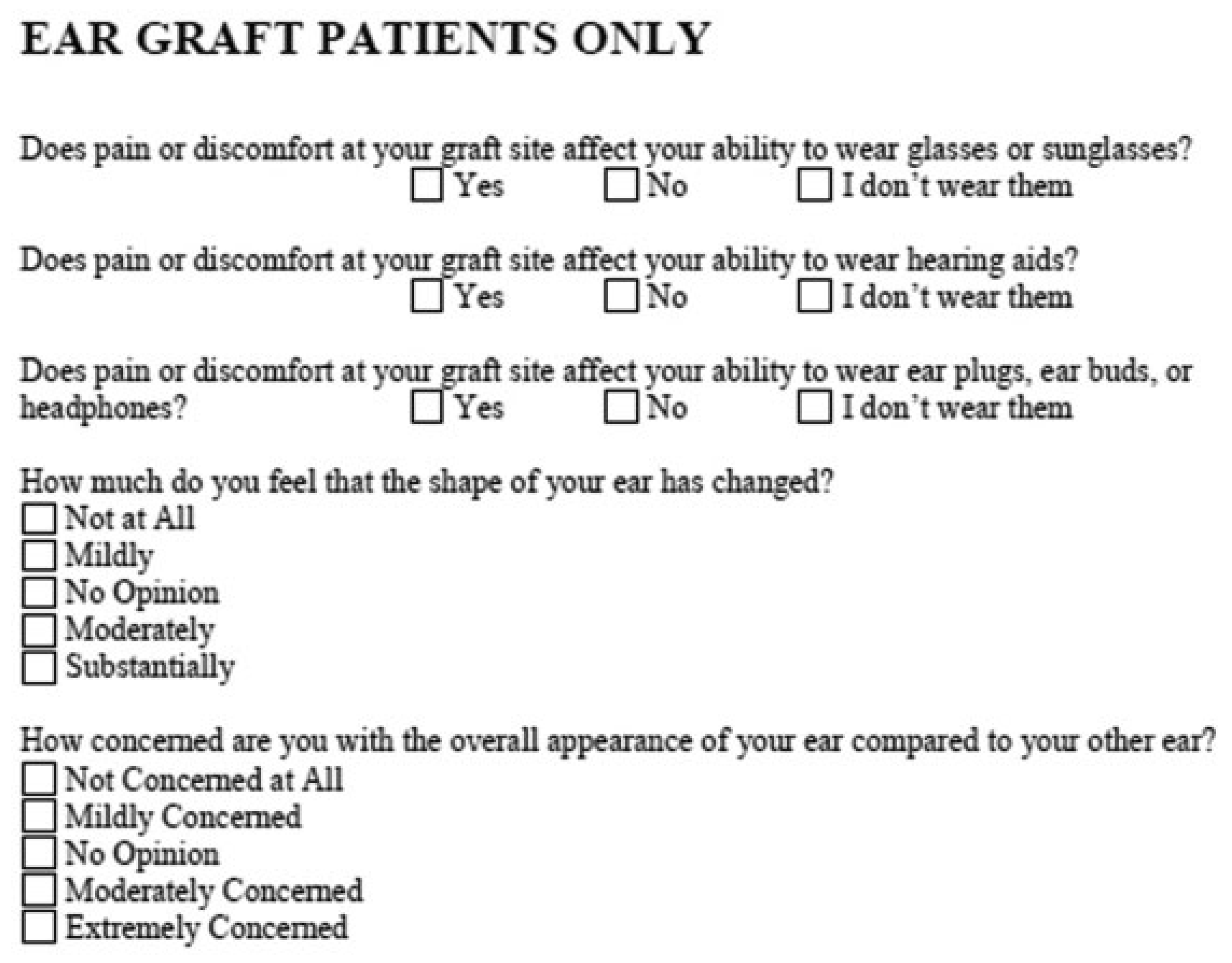

The survey assessed general pain, nasal pain, pain at the graft donor site, graft donor site scar itching, color variation, skin stiffness and thickness, and graft donor site appearance relative to normal skin. All three pain scales were assessed using a Likert-type numerical rating scale ranging from 0 to 10 (no pain to severe pain); this scale is sensitive to changes in pain over time after surgery.[

6] For the ear cartilage graft patients, there were additional questions asked regarding the patient’s ability to wear glasses and hearing devices (e.g., hearing aids, headphones) and the patient’s perception of the shape and appearance of the operated ear. A copy of the patient survey is included in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

All data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the KUMC.[

7] The database included demographics, surgical details, and the responses to patient-completed surveys. Differences in categorical variables between graft sites within visits were compared using χ

2 and Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann–Whitney) tests were performed to compare graft site– specific pain scores within visits and to compare the changes over time across the graft sites. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was utilized for the test of changes between visits within the graft sites. All statistical comparisons were made using SPSS statistical software (version 22; IBM Corp).

Results

Our patient cohort was 55% female (n = 30) with a mean age of 47 years. Among the 55 nasal surgeries, 31 utilized auricular cartilage, and 24 used costal cartilage. There were no donor site–related surgical complications.

In terms of survey participation, 55 patients completed the surveyat 1 week postoperatively. This number decreased to 44 patients, 33 patients, and 8 patients at 1, 3, and 6 months out from surgery, respectively. However, our sample size calculations targeted comparisons at the 3-month postoperative visit. We did continue to collect data up to 6 months after surgery for those patients who returned to the clinic for this optional follow-up but did not include the data from the 6-month visit in our analysis given its limited availability.

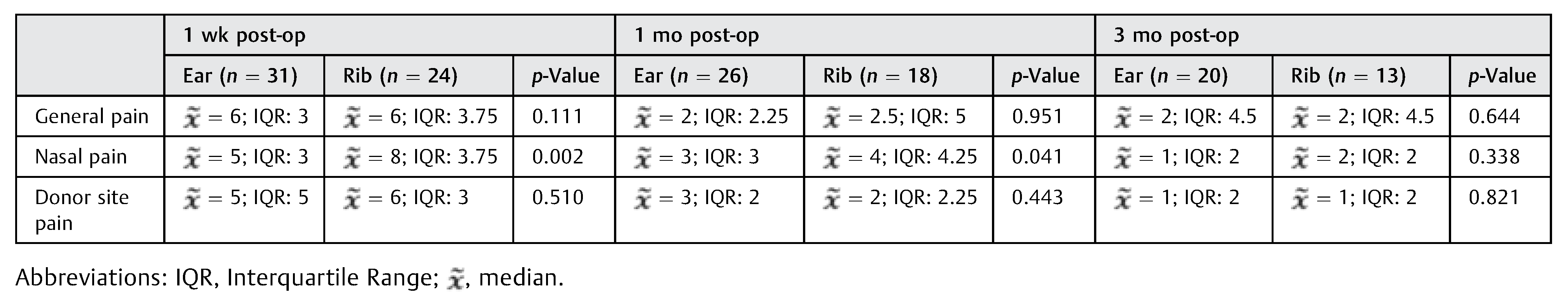

There were no statistically significant differences in the median general pain and donor site pain scores across all postoperative visits, which regardless decreased over time (

Table 1). For nasal pain, the median values for rib cartilage grafts at 1 week (8; interquartile range [IQR]: 3.75) were significantly greater (

p = 0.002) than those for ear cartilage grafts (5; IQR: 3). At 1 month postoperatively, this significant difference between the two groups continued (4 vs. 3;

p = 0.041). However, by 3 months after the surgery, there was no longer a significant difference in nasal pain (2 vs. 1;

p = 0.338).

We also compared nasal pain between different types of nasal surgery (septorhinoplasty vs. nasal reconstruction) and found no statistically significant differences. When evaluating postoperative pain by surgeon, there were no statistically significant differences for all types of assessed pain. Among the ear cartilage graft patients, there were no statistically significant differences between anterior and posterior approach for general pain or nasal pain. Posterior approach patients did report significantly greater (p = 0.026) donor site pain at 3 months out from surgery (3 vs. 1 on the pain scale, respectively).

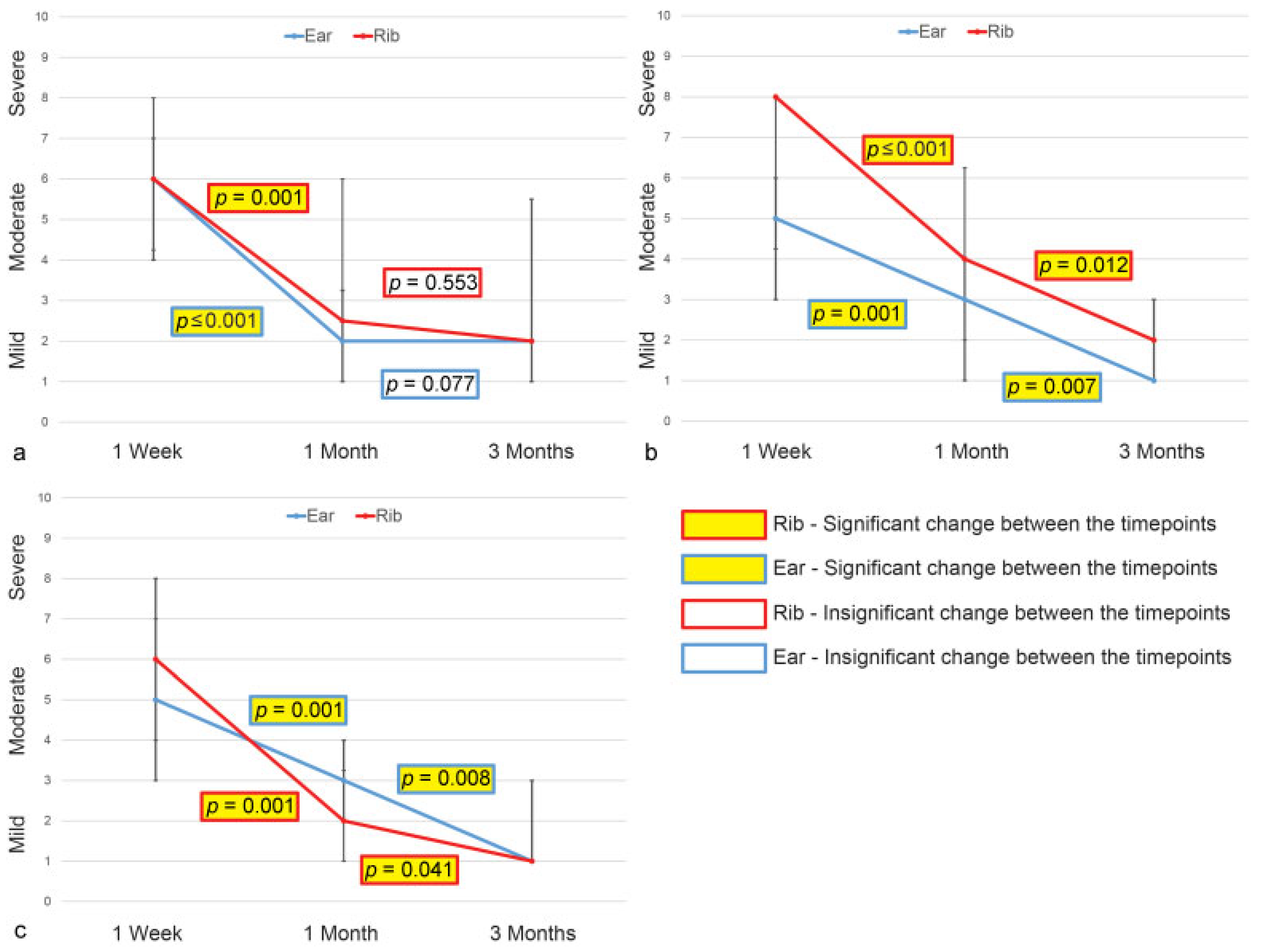

In addition to comparing types of postoperative pain at each postoperative visit, we also tracked patient pain scores over time (

Table 2). For general pain, the pain scores for both rib and ear cartilage graft patient groups significantly decreased from 1 week to 1 month postoperatively (rib:

p ≤ 0.001; ear:

p = 0.001;

Figure 3a). Likewise, nasal pain scores declined across the postoperative visits with significant differences observed from 1 week to 1 month (rib:

p = 0.001; ear:

p ≤ 0.001) and 1 to 3 months (rib:

p = 0.007; ear:

p = 0.012) for both groups, as illustrated in

Figure 3b. Donor site pain scores also decreased over time (

Figure 3c). For ear cartilage graft patients, there were significant differences from 1 week to 1 month (

p = 0.001) and from 1 to 3 months (

p = 0.008). The same was true among the rib cartilage graft patients from 1 week to 1 month (

p = 0.001) and from 1 to 3 months (

p = 0.041). Analysis of the median magnitude of change for the two groups between visits revealed only a significant difference in median decline for nasal pain from 1 week to 1 month postoperatively (

p = 0.039).

We compared nasal pain versus donor site pain among all patients and within each cartilage graft group. The results are depicted in

Table 3. Our findings showed that nasal pain was significantly greater than donor site pain for rib cartilage graft patients at 1 week and 1 month after surgery (

p = 0.038 and

p = 0.044, respectively). Donor site pain trended greater than nasal pain for the ear cartilage graft patients at 1 week and 1 month after surgery, but the differences were not statistically significant (

p = 0.335 and

p = 0.314, respectively).

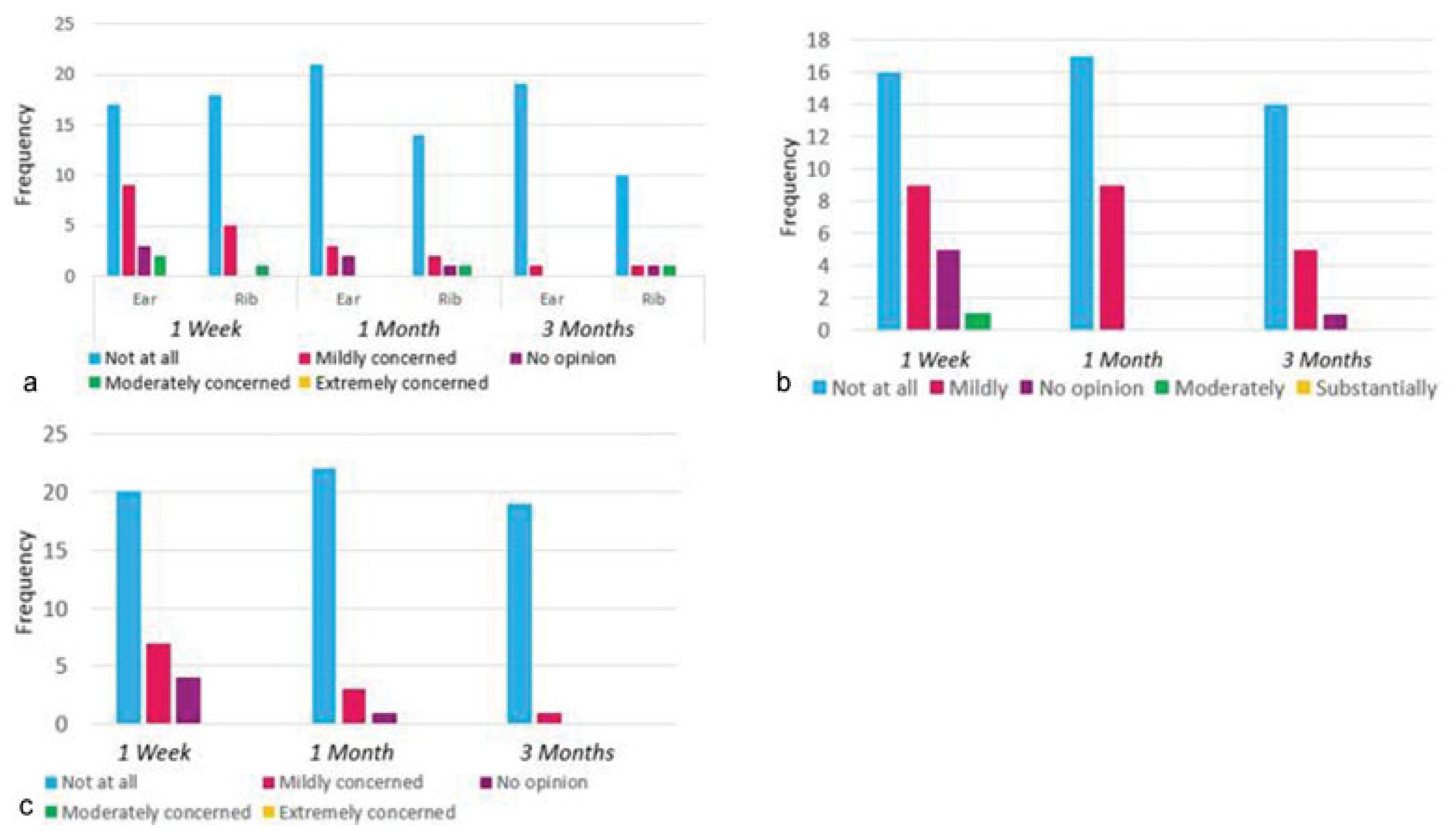

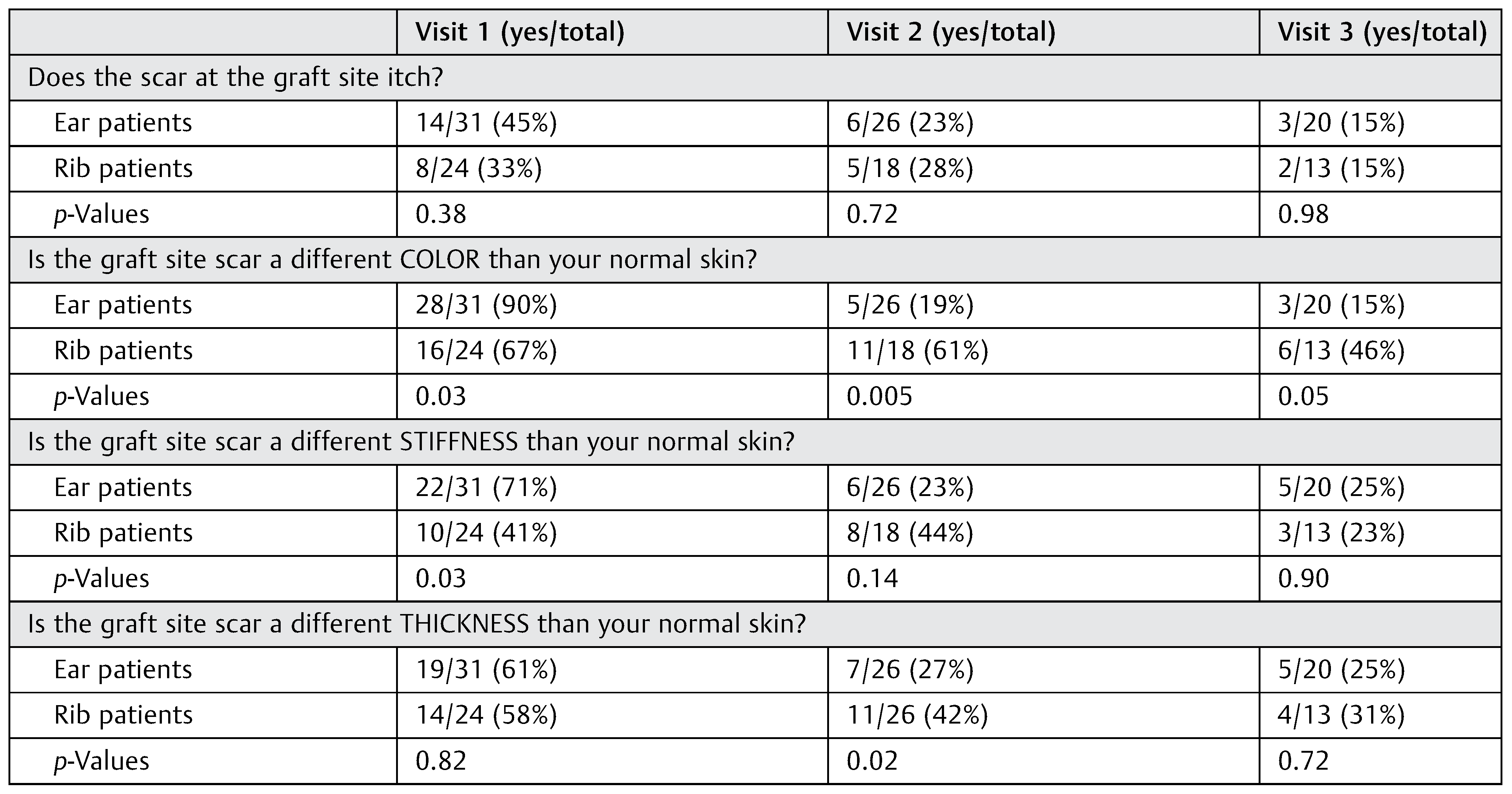

There were no significant differences between the ear and rib cartilage graft patients for scar itching, with the number of patients reporting decreasing scar itching over time (

Table 4). The number of patients noticing a difference in scar color, thickness, and stiffness diminished over time for both groups with some instances of significant difference that occurred between the two groups at various time points after surgery (

Table 4). When comparing survey results by surgeon, there were no statistically significant differences for scar itching, color, stiffness, thickness, and overall scar appearance for all postoperative visits. Furthermore, the majority of patients indicated across all visits that they were “not at all” concerned with their scar appearance, as demonstrated in

Figure 4a.

Most patients responded that they did not wear hearing aids, ear buds, ear plugs, or headphones. More than half of the ear cartilage graft patients (16/31) experienced pain or discomfort with wearing glasses or sunglasses 1 week out from surgery. This number decreased to three patients 1 month after surgery (3/26) and no patients 3 months after surgery (0/20). Most ear cartilage graft patients answered “not at all” in regard to how they felt their ear shape had changed and to their concern with the overall appearance of their operated ear compared with the contralateral ear (

Figure 4b, c).

Discussion

Although facial plastic surgeons have utilized costal and auricular cartilage in nasal surgery for decades, literature on postoperative cartilage graft donor site recovery and complications following nasal surgery remains limited. Conventional wisdom ascribes that utilization of auricular and particularly costal cartilage results in high levels of donor site pain relative to nose pain, though this has not been verified in the literature either. In addition, rib cartilage harvest morbidity has not previously been studied relative to other harvest sites such as the ear.

When it comes to ear cartilage graft donor site morbidity, a 2004 retrospective review by Murrell on his 8-year experience of nasal surgeries using auricular cartilage graft briefly described two patients with donor site ulceration with one resulting in a pinpoint fistula and one patient dissatisfied with the position of the operated ear postoperatively.[

8] A 2008 study by Mischkowski and colleagues evaluated short-term and long-term donor site morbidity associated with different types of ear cartilage grafts. The most common early and late complications, respectively, were hematoma formation (6.7%) and sensory impairment (12.9%). Anthropometric measurements showed differences in length, width, tragus/lateral canthus distance, and protrusion between operated ears and nonoperated ears, but without statistical significance.[

9] The study by Mischkowski et al concluded that ear cartilage graft harvest is an overall safe procedure, and while the concha demonstrated the highest morbidity among the ear donor sites, its advantages outweighed the risks.

In regard to rib cartilage postoperative outcomes, Yang and colleagues assessed donor site morbidity of a minimally invasive costal cartilage harvest technique for patients requiring mastoid obliteration. Their study showed a mean duration of noticeable pain 5.3 days postoperatively and a mean pain score of 3.0/10 on the first day of surgery with subsequent decline.[

10] The cosmetic score for the costal cartilage donor site was comparable to that for the postauricular incision site with no statistical significance observed. One patient suffered wound dehiscence, and another experienced keloid formation; otherwise there were no major complications.[

10] A 2015 meta-analysis by Wee et al[

11] on rhinoplasty complications associated with rib cartilage grafting found the following rates of postoperative issues: warping, 3.8%; resorption, 0.22%; infection, 0.56%; displacement, 0.39%; hypertrophic chest scarring, 5.45%; and revision surgery, 14.7%.[

9] This article determined that the overall long-term complications pertaining to rib cartilage graft harvest were low.

The aim of our study was to prospectively assess costal and auricular cartilage donor site pain and morbidity in patients undergoing rhinoplasty and nasal reconstruction. Our analysis revealed no significant difference between cartilage donor site pain and nasal pain in patients undergoing ear cartilage grafting. Patients who underwent rib cartilage grafting had significantly greater nasal pain than cartilage donor site pain. This finding suggests that patients who require costal cartilage harvest are undergoing more extensive nasal surgery, but additional study would be necessary to confirm this assertion. Finally, there was no significant difference in cartilage donor site pain between patients undergoing ear versus rib cartilage grafting. These findings challenge the notions that donor site pain exceeds nasal pain for most patients undergoing rib or auricular cartilage harvest and that donor site pain is greater following rib cartilage harvest.

In regard to scar characteristics, there were no persistent significant differences in scar itching, color variation, skin stiffness, and skin thickness between the rib and ear cartilage graft groups over time. Nearly all patients reported that they were not at all concerned about their scar appearance or their ear shape and appearance. The study patients in general experienced minimal, if any, morbidity related to donor site appearance or scarring. Overall, our findings confirmed our hypothesis that morbidity at both rib and ear cartilage graft donor sites would be minimal.

We acknowledge several limitations of this pilot study. First, all conclusions were based on subjective data. Our results may have been different if supplemented by an objective analysis component derived from measurements or clinical evaluation. Moreover, problems with patient retention caused our sample size to decline over time. We initially enrolled 55 patients aiming to account for some dropout at the 3-month mark, but ended with 33 patients (60%). There is also some variance in surgical technique between the two surgeons. This was particularly true for the ear cartilage group, as one surgeon consistently used the anterior approach while the other relied on the posterior approach. We did specifically perform a comparison analysis by surgeon and did not observe any statistically significant differences between patients who underwent an anterior versus posterior approach.

Conclusion

Although the surgical techniques for costal and auricular cartilage graft harvest are well described, very limited literature exists on cartilage graft donor site morbidity following nasal surgery. Our pilot study analyzed costal and auricular cartilage donor site pain and morbidity in rhinoplasty and nasal reconstruction patients and found no significant difference in donor site pain between the two harvest sites. Knowledge of similar and minimal morbidity at both rib and ear cartilage graft donor sites allows facial plastic surgeons to be more inclined to use rib or ear cartilage for nasal surgery and to simply select the donor site based on the type of grafting material needed.