Occlusal stabilization is an important component of the repair of mandibular fractures. The arch bar has remained the mainstay in the closed reduction of mandibular fractures since World War I. The procedure, however, is risky and predisposes the operator or assistant to the threat of percutaneous injury by wire ends and a high chance of serological transmission of diseases [

1]. In addition, intraoperative maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) with arch bars has other significant disadvantages, which include a prolonged duration of application and compliance issues among the patients. To overcome the limitations of multiple wires and for safety of the operator, several other techniques for MMF have been proposed, which include the use of intermaxillary fixation (IMF) screws [

2,

3] or manual(anatomical) reduction of the occlusion [

4,

5] and the use of embrasure wires [

6,

7]. The embrasure wire is quite simple and reliable technique, including the use of limited wire application, less time of application, fewer chances of disease transmission in case of wire prick injury especially in the hepatitis and HIV-inflicted patients, and cost-effective. These advantages certainly allow surgeons to overcome the cons associated with the arch bar. However, in terms of stability, the role of embrasure wiring is questionable [

8].

The purpose of this prospective study was to revisit and evaluate the efficacy of embrasure wiring over the arch bars for MMF in the management of mandibular fractures undergoing open reduction and internal fixation based on the parameters such as time taken for placement, safety of the operator and assistant, stability of occlusion during open reduction and plate fixation, the ease of placement and removal of wires, and the success of the final outcome via evaluation of factors such as postoperative occlusion and finally the cost factor.

Materials and Methods

This prospective randomized study was conducted at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, performed from June 2013 to August 2015. The institutional reviewer board and the local ethical committee have approved the study. This study followed the criteria as declared by Helsinki.

In this study, 40 adult patients without any systemic complications, who strictly met the inclusion criteria, were included. The inclusion criterion was isolated mandibular fractures (single or multiple) which require open reduction and internal fixation. The exclusion criteria were mandibular fractures with infection; unilateral or bilateral condylar fractures; patients with generalized interdental spacing; and a history of diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, prolonged steroid therapy, compromised immunity, or associated bone pathologic features, alcoholics, and fracture older than 7 days.

The diagnosis was made on the basis of the clinical examination findings and radiographic interpretation. Routine investigations were performed. All patients provided informed consent before participating in the study. Randomization of consecutive patients was done using slot method, irrespective of age and gender. To remove the bias, a single surgeon had operated on all the patients under standard aseptic conditions and protocol. The individuals were randomly allotted to either group A (embrasure wire) or group B (arch bar). Patients in both the groups were treated by open reduction and internal fixation, through an intraoral or extraoral approach using conventional miniplates and screws. Before fixation of the miniplates, embrasure wire or arch bars were applied among patients of both groups intraoperatively. Open reduction and internal fixation for all patients were done under general anesthesia with nasoendotracheal intubation. The MMF was continued in the postoperative period, if minor discrepancies exist in occlusion.

The cause of trauma, the interval from injury to surgery, average age, gender, and site distribution were all assessed. Follow-up was done at the end of postoperative first, third, and sixth weeks. The following clinical parameters were assessed for each patient: intraoperative time required for MMF, wire prick injury during MMF (glove penetration and finger puncture at the time of application), stability of occlusion during open reduction and internal fixation, postoperative malocclusion, and postoperative infection.

Technique for Embrasure Wiring

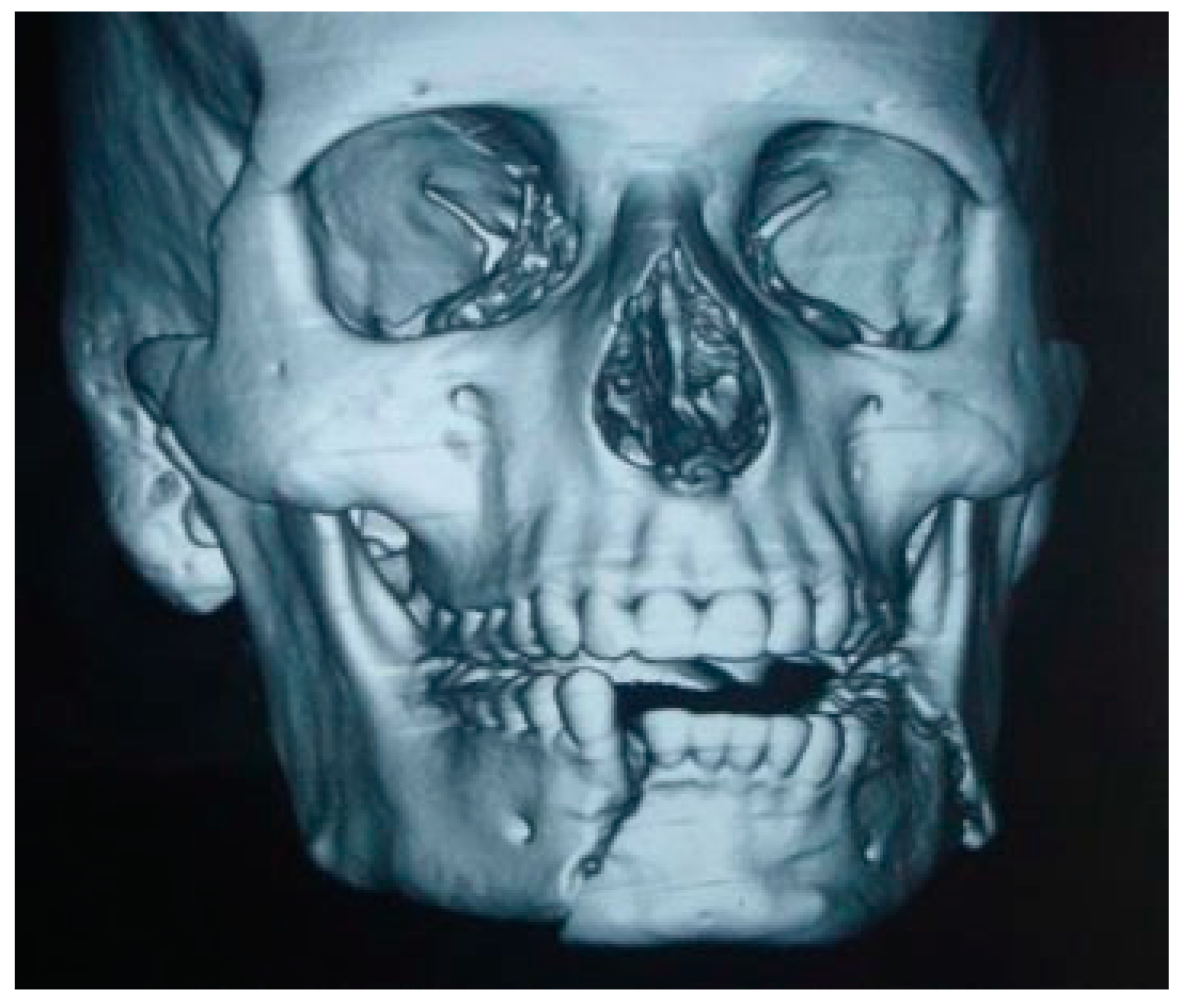

For the illustration of the technique, a case of left angle fracture with right parasymphysis fracture of the mandible has been depicted (

Figure 1). With the mouth open, stainless steel wires (24 gauge) approximately 15 cm were introduced through the facial embrasure between the maxillary molars, premolars, and the maxillary central incisors. Next, the palatal end of the wire is looped and then passed through the opposing lingual embrasure in the mandible (

Figure 2).

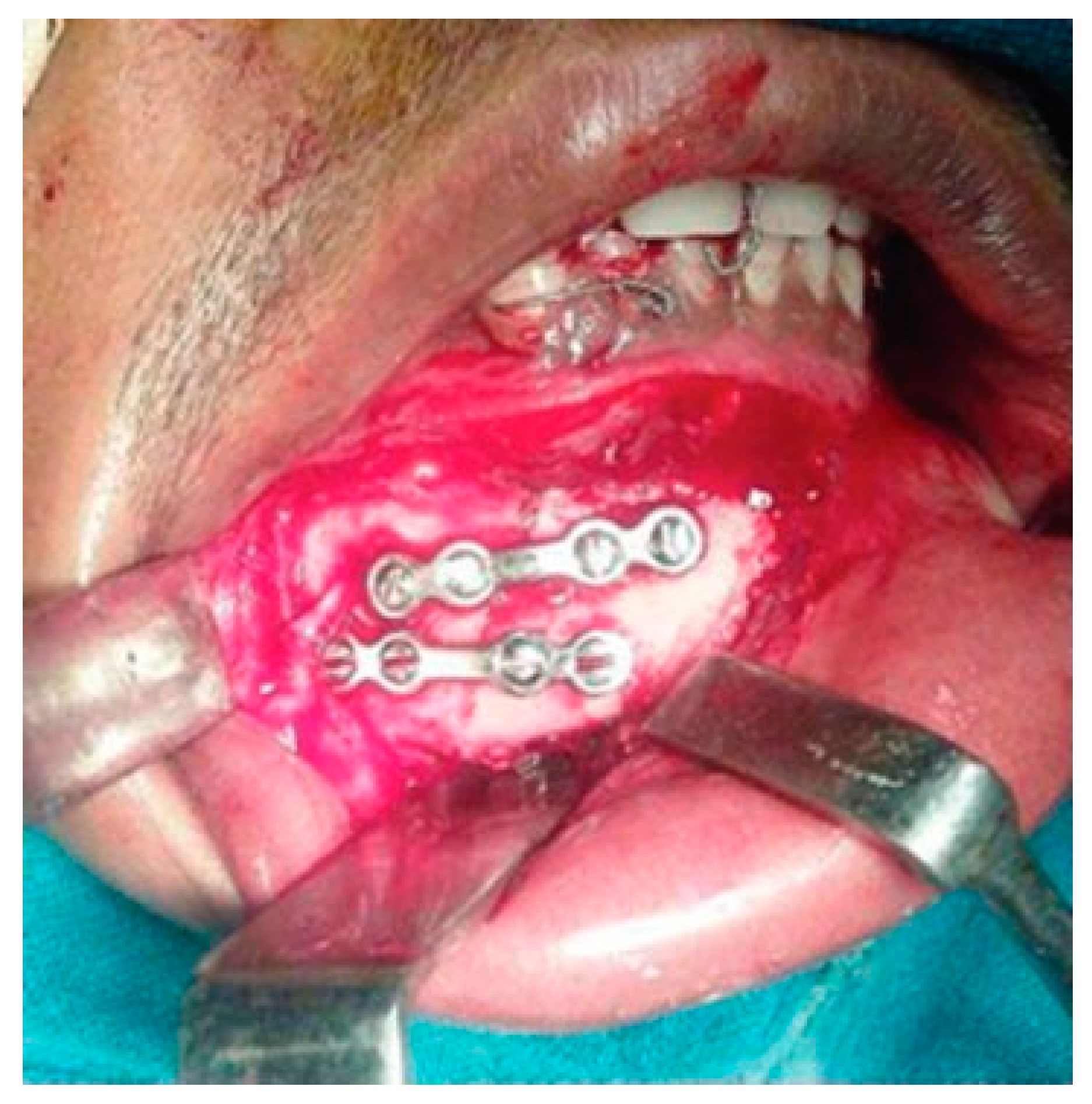

Next, the fracture sites were exposed and segments were reduced appropriately, and then all the embrasure wires were twisted together until the fixation is rigid. It is very important to reduce the fractures before twisting the wires. After achieving functional occlusion along with anatomical reduction, fractured segments are fixed with miniplates and screws (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Unlike arch bars, the embrasure wires provide superior stability, which could prevent fracture reduction once IMF has been established (

Figure 5).

Figure 1.

Preoperative CT scan showing right parasymphysis and left angle fracture.

Figure 1.

Preoperative CT scan showing right parasymphysis and left angle fracture.

Figure 2.

Bilateral placement of embrasure wires around the interproximal contacts between molars, premolars, and central incisors in respective arches.

Figure 2.

Bilateral placement of embrasure wires around the interproximal contacts between molars, premolars, and central incisors in respective arches.

Figure 3.

Excellent stability of anatomically reduced fractured segments after internal fixation with miniplates.

Figure 3.

Excellent stability of anatomically reduced fractured segments after internal fixation with miniplates.

Ideally, normal interproximal contacts are necessary to achieve good fixation. The occlusion can then be established by matching the opposing wear facets on the teeth. When removing the fixation, the wires should be cut close to the teeth. Gentle pressure is placed on the maxilla and mandible to help open the mouth slightly. Next, a periosteal elevator or a wire pusher is gently used to push the wire toward the tongue and the wires were removed.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPPS (version 11.5; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). An unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare the significance of differences between the means of the two groups, the chi-square test was used to compare the proportion of two groups, and probabilities of less than 0.05 were accepted as significant.

Figure 4.

Excellent stability of anatomically reduced fractured segments after fixation.

Figure 4.

Excellent stability of anatomically reduced fractured segments after fixation.

Results

A total of 40 patients with 53 fractures who met the inclusion criteria were included in the study. The mean age of the patients in group A (embrasure wire) was 26.75 11.27 years as compared with group B (arch bar) which was 29.05 9.90 years (

Table 1). Males were commonly affected in both the groups (80–85%) in comparison to females (15–20%;

Table 2). The most common site of fracture in terms of anatomic location in both the groups (A and B) was isolated parasymphysis fracture (25–35%), whereas combination fractures (angle and parasymphysis) account for 15 to 25% in both the groups (A and B;

Table 3). The most common cause of injury was road traffic accidents in both the groups (60–65%;

Table 4).

Figure 5.

Postoperative orthopantomography reveals the adequate reduction and internal fixation of fractured segments following placement of embrasure wires.

Figure 5.

Postoperative orthopantomography reveals the adequate reduction and internal fixation of fractured segments following placement of embrasure wires.

Table 1.

Age distribution in group A and group B.

Table 1.

Age distribution in group A and group B.

| Age group | Group A | Group B |

|---|

| Number of patients | % | Number of patients | % |

|---|

| 16–20 | 10 | 20 | 3 | 6 |

| 21–30 | 3 | 6 | 11 | 22 |

| 31–40 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 8 |

| 41–50 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| 51–60 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 20 | 100 | 20 | 100 |

Table 2.

Sex distribution in group A and group B.

Table 2.

Sex distribution in group A and group B.

| Sex | Group A | Group B |

|---|

| Number of patients | % | Number of patients | % |

|---|

| Male | 17 | 85 | 16 | 80 |

| Female | 3 | 15 | 4 | 20 |

| Total | 20 | 100 | 20 | 100 |

Furthermore, the preoperative occlusion was deranged in all the patients in both the groups; however, functional occlusion was achieved in all the patients. The average time interval between injury and treatment was 5 days. The time required for MMF in group A was 7.85 0.81 minutes as compared with 45.05 5.96 minutes in group B, which was proved to be highly statistically significant (

p ¼ 0.0000;

Table 5).

In terms of complications related to wire prick injury, statistically significant difference was found between the two groups (

p ¼ 0.0264;

p < 0.05). However, no statistically significant difference was found among the clinical parameters, such as malocclusion and infection, between the two groups (

p > 0.05;

Table 6).

Table 3.

Fracture location in group A and group B.

Table 3.

Fracture location in group A and group B.

| Fracture location | Group A | Group B |

|---|

| No. | % | No. | % |

|---|

| Right angle, left parasymphysis | 2 | 10 | 1 | 5 |

| Left angle | 2 | 10 | 2 | 10 |

| Right parasymphysis, left angle | 3 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Right parasymphysis | 3 | 15 | 4 | 20 |

| Left parasymphysis | 4 | 20 | 1 | 5 |

| Symphysis | 2 | 10 | 2 | 10 |

| Right angle | 1 | 5 | 3 | 15 |

| Right body | 1 | 5 | 2 | 10 |

| B/L parasymphysis | 1 | 5 | 2 | 10 |

| Right body, left parasymphysis | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Left parasymphysis, right angle | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Right angle, right parasymphysis | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Total | 20 | 100 | 20 | 100 |

Table 4.

Cause of injury in group A and group B.

Table 4.

Cause of injury in group A and group B.

| Cause of injury | Group A | Group B |

|---|

| No. | % | No. | % |

|---|

| RTA | 13 | 65 | 12 | 60 |

| Domestic violence | 3 | 15 | 3 | 15 |

| Fall from height | 2 | 10 | 3 | 15 |

| Sports injury | 2 | 10 | 2 | 10 |

| Total | 20 | 100 | 20 | 100 |

Table 5.

Time required for MMF in group A and group B.

Table 5.

Time required for MMF in group A and group B.

| Group | Time required for MMF |

|---|

| Mean SD | p-Value |

|---|

| Group A | 7.85 0.81 | 0.0000 (HS) |

| Group B | 45.05 5.96 |

Discussion

The successful practice of trauma surgery entails due consideration to the principles of fracture reduction, that is, proper anatomical reduction and rigid fixation. Most of the untoward postoperative sequel that is encountered in the practice of maxillofacial trauma can be attributed in one way or several to the overlooking of these fundamental underlying principles. In this regard, the role of MMF cannot be understated. Several techniques have been proposed in the literature for performing MMF [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Hammond [

9] in 1870 was the first who introduced the arch bar in oral and maxillofacial surgery for the treatment of maxillomandibular bony injuries. After that Sauer in Germany and Gilmer in the United States [

9] applied a simple round bar that was adapted to the teeth with brass ligature wires. Later on, Blair and Ivy [

10] modified the original round arch bar into a flattened arch bar on one side to provide better adaptation to the teeth and provide enhanced stability. Arch bars with eyelet wires have been the traditional method of MMF. However, the technique has several disadvantages, with the time required for the application being the most common. The increased time required for application in general anesthesia leads to increased costs. Also, the risk of disease transmission through wire prick, risk of dental caries, the presence of periodontal disease, and an allergy to metals, among others, have been noted [

11]. Over the years, many modifications have been proposed by various authors to overcome the limitations of the arch bar [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The comparison of both groups in terms of time taken for the placement of MMF using embrasure wires/arch bars revealed a statistically highly significant difference (

p < 0.001), thereby making embrasure wires a comparatively much quicker procedure. The mean time (minutes) taken for group A (embrasure wires) was 7.85 0.81 minutes, whereas for group B (arch bars) it was 45.05 5.96 minutes. A similar statistically significant time difference was reported by Engelstad and Kelly [

6] between the arch bar and embrasure wires (25.5 vs. 2.5 minutes). Hence, the study, as well as contemporary literature, favors the use of embrasure wires in situations where intraoperative time is of greater significance.

Table 6.

Complications in group A and group B.

Table 6.

Complications in group A and group B.

| Complications | Group A | Group B | p-Value |

|---|

| N ¼2 0 | N ¼ 20 | p < 0.05

(significant) |

|---|

| Wire injury during MMF | 0 | 4 (20) | 0.0264 (S) |

| Postoperative infection | 1 (5) | 3 (15) | 0.5982 (NS) |

| Hardware failure | 0 | 1(5) | 0.1852 (NS) |

| Malocclusion | 0 | 0 | |

The incidence of intraoperative complications has traditionally remained one of the chief pitfalls of using arch bars for MMF. Sharp wire ends may lead to prick injury which might result in the transmission of infections during the procedure. In our study, none of the surgeon and assisting surgeons encountered prick injury during placement of the embrasure wire intraoperatively (group A); however, in the group B (arch bar) a high incidence of wire injury during MMF was reported, that is, 4 cases out of 20 (20%) which is considered to be statistically significant (

p < 0.05). Similarly, the presence of postoperative infection was noted in three cases in group B (15%) in contrast to one case in group A (5%), perhaps attributed to the traumatic placement of the arch bar (excessive manipulation of the fractured segments, trauma to the soft tissues, and poor oral hygiene). While the embrasure wires clearly are a better alternative in terms of intraoperative wire injuries, they have often been attributed to a variety of causes of postoperative failure such as malocclusion due to lack of stability [

10]. In our study, a statistical comparison of the postoperative complications in respect of hardware failure and malocclusion in both the groups (A and B) was found to be nonsignificant (

p > 0.05), that is, none of the patients had postoperative malocclusion in both the groups. These findings suggest that embrasure wiring and arch bar provide adequate stability of the fractured segments during reduction of the segments intraoperatively.

Tracy and Gutta [

7] in their comprehensive review study on 86 patients determined hardware failure was the most common complication in both the groups: 12% in the embrasure group and 15% in the arch bar group. This was in contrast with our results. Furthermore, in their study, the patients in the arch bar group (7.5%) had a slightly greater incidence of postoperative malocclusion than did the embrasure group (6%). The incidence of infectious complications was greater in the arch bar group (13%) than in the embrasure group (9%). However, these findings did not match our study.

A detailed evaluation of the postoperative complications, when determined by the anatomical site, aids the surgeon to assess in depth the incidence of the postoperative complications, keeping in mind the constraints offered by the specific anatomical location of the fractured segments that could have knowingly or unknowingly contributed toward these complications. In our study, the assessment of the location of the fractured segments based on anatomical site revealed that the wire prick injury was common in group B (arch bars) when the fracture line was present more posteriorly, that is, at right angle with left parasymphysis fracture, right parasymphysis fracture, right angle fracture, and right body fracture. On the other hand, no such complications were seen in group A (embrasure wires). In addition, postoperative infections were evident in group B, while group A presented only one such complication at bilateral parasymphysis fracture. A comparative evaluation of a similar anatomical stratification by the postoperative complications was observed and presented in the study of Tracy and Gutta [

7], which reveals that incidence of postoperative complications is more in the embrasure wire group. These correlations reveal that neither of the studies presented a definitive correlation of a particular anatomical site with a particular type of complication and that the distribution of the complication seems to be uniformly spread over various anatomical sites. Hence, the results of the earlier-mentioned study did not correlate with our data (

Table 7).

In lieu of the cost of placement, embrasure wire fixation costs significantly less than arch bar fixation. The only cost for the embrasure wire IMF is a single stainless steel wire. At our institution, the anesthesia-related charges for arch bar placement in the operating room range from 50 to 100 USD, depending on the length of the procedure (range: 40–100 minutes). The surgical fee for arch bar removal is 10 to 20 USD. Although arch bars can be removed under local anesthesia, some surgeons prefer to perform the procedure in the operating room, hence increasing the cost. The cost of arch bar placement/removal in the operating room adds at least 100 to 150 USD for the anesthesia and 100 USD per hour toward the anesthetist charges. Thus, with conservative measures, the cost savings would be 150 to 200 USD per patient using embrasure wire IMF which is a significant saving. Whether the surgeon or the hospital recovers these costs for arch bar placement is a different issue. In addition to the cited costs, several indirect costs are associated, including time off from school or work to undergo arch bar removal and the cost of repair of associated dental complications such as dental caries and periodontal disease.

Table 7.

Complications stratified by fracture location in group A and group B.

Table 7.

Complications stratified by fracture location in group A and group B.

| Complications | Group A | Group B |

|---|

| Wire injury during MMF |

| Right angle, left parasymphysis | 0 | 1 |

| Right parasymphysis | 0 | 1 |

| Right angle | 0 | 1 |

| Right body | 0 | 1 |

| Post-op infection |

| Right angle, left parasymphysis | 0 | 1 |

| Right angle | 0 | 1 |

| B/L parasymphysis | 1 | 0 |

| Right angle, right parasymphysis | 0 | 1 |

| Hardwire failure |

| B/L parasymphysis | 0 | 1 |

| Malocclusion |

| Right angle, left parasymphysis | NIL | NIL |

| Left angle | NIL | NIL |

| Right parasymphysis, left angle | NIL | NIL |

| Right parasymphysis | NIL | NIL |

| B/L parasymphysis | NIL | NIL |

Conclusion

Our study renders a definitive glimpse into the comparative advantages and disadvantages of both the techniques. However, no statistically significant difference in outcomes was found between the two study groups, other than the time taken for the procedure and a lower incidence of wire prick injury associated with embrasure wire IMF. With the additional associated health care costs and lower socioeconomic status prevalent in the population, it is very important to consider the increased costs in the operating room, the cost of removing the arch bars, and the dental complications associated with the use of arch bars. Compared with IMF using arch bars, the results of the study have shown that IMF with embrasure wires results in fewer clinical complications. Larger, more definitive studies are needed to determine the validity of these results.