Abstract

Mandibular midline distraction (MMD) is a relatively new surgical technique for correction of transverse discrepancies of the mandible. This study assesses the amount and burden of complications in MMD. A retrospective cohort study was performed on patients who underwent MMD between 2002 and 2014. Patients with congenital deformities or a history of radiation therapy in the area of interest were excluded. Patient records were obtained and individually assessed for any complications. Complications were graded using the Clavien-Dindo classification system (CDS). Seventy-three patients were included of which 33 were males and 40 were females. The mean follow-up was 2.1 years. Twenty-nine patients had minor complications, grades I and II. Two patients had a grade IIIa and three patients had a grade IIIb complication. Common complications were pressure ulcers, dehiscence, and (transient) sensory disturbances of the mental nerve. This study shows that although MMD is a relatively safe method, complications can occur. Mostly the complications are mild,transient, and manageable without the need for any reoperation.

In the 1990s, a surgical technique to widen the mandible called mandibular midline distraction (MMD) was introduced. The indications for the procedure include anterior and posterior crowding and a uni- or bilateral crossbite.

The technique comprises a vertical osteotomy which is placed in the anterior mandible, preferably in the midline. A tooth-borne, bone-borne, or hybrid distractor is applied during or before surgery depending on the type of distractor. After a latency period of approximately 1 week, the distractor is activated until the desired widening is achieved. A period of 2 to 3 months of rest ensures consolidation of the two hemimandibles.

To adequately inform a patient before a combined orthodontic and surgical treatment, it is necessary to tell them not only about the effectiveness but also the risks. Since the introduction of MMD, research focused largely on the biomechanical effectiveness of the technique. These studies show stable results of the treatment over time, with little relapse [1,2]. Less attention was aimed at the amount and impact of complications that can occur during the surgery and distraction period. Von Bremen et al. presented a comprehensive study on the complications in the first 2 weeks after MMD using a tooth-borne distractor [3]. Mommaerts et al. studied the morbidity of MMD using the success criteria for craniofacial distraction osteogenesis as proposed by the steering group of European Collaboration on Cranial Facial Anomalies [4]. These studies are either limited in their follow-up period or include a relatively small number of patients. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the number of complications using MMD in a comprehensive patient cohort with a long follow-up period.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted with the approval of the Standing Committee on Ethical Research in Humans of the Erasmus MC, University Medical Centre Rotterdam (MEC 2013–367). A retrospective cohort study was performed. Inclusion criteria were transverse mandibular discrepancy, treated with MMD, and at least 16 years of age. Exclusion criteria were patients with congenital craniofacial deformity and history of radiation therapy in the area of interest.

The surgical technique used was similar to that described by Mommaerts et al. [5] When a tooth-borne distractor was used, an orthodontist preoperatively placed the distractor. All patients who underwent MMD in the Erasmus University Medical Centre Rotterdam, the Netherlands, between 2002 and 2014 and fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included. The medical records were obtained and hand searched for complications during the surgical procedure and follow-up period.

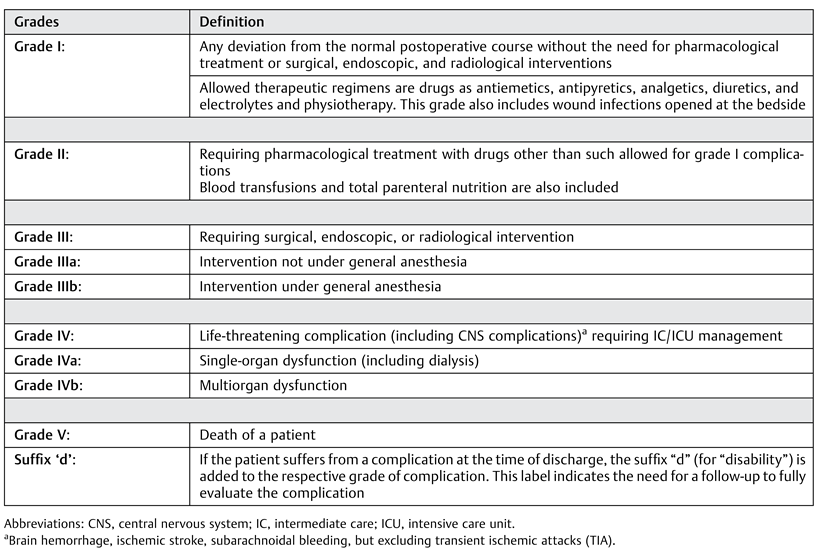

The CDS classification was applied to grade the severity of the complications (Table 1) [6]. Furthermore, the (transient) adverse outcomes were categorized. Grades I and II are considered as minor complications and from grade IIIa onwards as major.

Table 1.

Clavien-Dindo classification.

Results

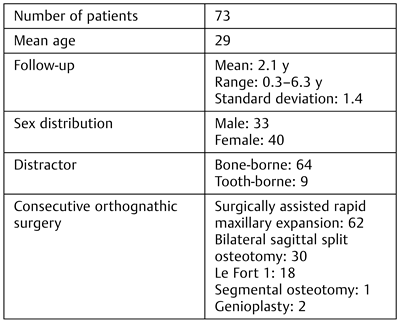

A total of 73 patients were included, 33 males and 40 females (Table 2). The mean age at the time of surgery was 29 years and the mean follow-up time was 2.1 years. Sixty-four patients were treated with a bone-borne distractor and 9 with a tooth-borne distractor. Sixty-two patients also underwent simultaneous surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion (SARME), mostly during a bimaxillary expansion (BiMEx) procedure. After the initial widening procedures, the following orthognathic surgeries were performed: bilateral sagittal split osteotomy, Le Fort I osteotomy, segment osteotomy, and genioplasty.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics.

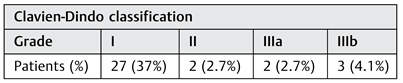

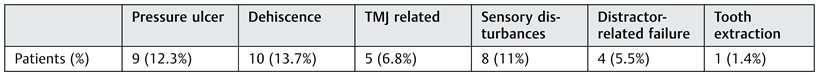

Complications that occurred included wound dehiscence, pressure ulcers, extraction of teeth, and reoperations (Table 3 and Table 4). Consequently, the CDS grade ranged from I to IIIb. Included in group I (37%) were wound dehiscence (13.7%), pressure ulcers (12.3%), (transient) sensory deficits (11%), and (transient) temporomandibular joint complaints (6.8%). The (transient) sensory deficiencies included hypo- and paraesthesia of the mental nerve as described in the patient records. The (transient) temporomandibular joint complaints included transient joint tenderness and clicking of the joint. Grade I also included some distractor-related complications. In one patient, the distracter bent at the end of the distraction period (Figure 1). Enough widening was achieved; however, the distraction gap was in V-shape. Another patient was activating the distractor in the wrong direction. Fortunately, it was observed on time and could be reversed. A grade II (2.7%) was scored in two patients who needed antibiotic treatment: in one case as a result of wound infection, and in the other as a result of severe gingivitis. In the latter case, the patient was too afraid to brush her teeth after the procedure. The IIIa grade (2.7%) was scored when a patient needed extractions of two teeth following periodontal decay after MMD and a second patient needed release of mucosal adhesions which emerged after MMD. The three patients who scored a grade IIIb complication (4.1%) needed a second surgical procedure under general anesthesia. In the first patient, the distractor type was too small to obtain adequate expansion of the mandible and a second procedure with a larger distractor was necessary. A second patient required remodeling of the chin because of a palpable distraction gap, which was corrected during the already planned bilateral sagittal split osteotomy procedure. A third patient suffered from an insufficient expanding distractor and a new distractor needed to be placed to achieve enough widening.

Table 3.

Complications.

Table 4.

Number of complications.

Figure 1.

Bended distractor and V-shaped distraction gap.

Discussion

MMD, a relatively new technique, is considered a relatively safe method to widen the mandible [7]. This study confirms this opinion, with only five major complications (CDS grades IIIa and IIIb, 6.8%) and no mortalities or life-threatening complications in 73 patients. The most common complications in MMD are wound dehiscence and pressure ulcers and, although uncomfortable for the patient, an antibiotic regime was required to overcome an infection as result of wound dehiscence in only one instance.

The most serious complications were related to the distractor, either due to technical problems or usage of the distractor. Therefore, clear instructions on how to activate the distractor and strict follow-up are important factors to prevent distractor-related complications. In addition, when a patient is not able to reliably activate the distractor, due to physical disability or anxiety, family or relatives could be instructed to use the distractor.

In this study, mostly bone-borne distractors were used. The bulk of the bone-borne distractor is positioned close to the mucosa of the lower lip and this probably accounts for most of the pressure ulcers. The relatively high amount of wound dehiscence might be attributable to the position of the incision in the mucobuccal fold. First, this location of the incision ensures saliva and food accumulation in the wound, and second the labial fold is continuously moving which could compromise the healing process. As all surgeries took place in a teaching hospital, the complication rate could be a little higher than in a normal setting. Although every surgical intervention is performed under supervision, it cannot always prevent less skilled surgical techniques.

Many of the registered complications were related to the position of the bone-borne distractor, and although complications were mostly transient, they were still uncomfortable for the patients. A second procedure is always necessary to remove a bone-borne distractor. Therefore, at the end of the follow-up period, having used multiple variants of the bone-borne distractor types, a shift toward the use of tooth-borne distractors took place in our clinic. However, the effect of this shift on the amount and burden of the complications has not been evaluated yet.

The risk of acquiring a temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD) following MMD might cause orthodontists and maxillofacial surgeons to hesitate to indicate MMD. This study shows that only five patients had transient joint complaints, which were expressed in joint clicking and joint tenderness. In this study, patients were not systematically assessed on TMD. More in vivo research on the effect of MMD on developing TMD and joint remodeling preferably with state-of-the-art imaging techniques is necessary. Postoperative sensory disturbances were seen in 11% of the patients and while occurring in the minority of the patients in a transient fashion, this can be quite aggravating.

In surgery, complications can occur due to numerous factors, such as age, comorbidity, medical appliances used, and surgeons’ experience. In addition, different surgical procedures have various complication rates depending on complexity and proximity of critical tissues. Traditionally, in oral and maxillofacial literature, the main focus in research on surgical therapies has been describing the biomechanical and technical outcome of these therapies. Nowadays, an increase in research on patient’s experience and related outcomes, such as complications and cost-effectiveness of therapies, is reported.

When systematically evaluating complications, the use of a standardized grading system minimizes the subjective assessment of an observer. Furthermore, a grading system enables the comparison of complications with other studies. In general surgery, the CDS was created to systematically grade complications [6]. After revising the system in 2004, wide acceptance in the general surgical literature was obtained. In the oral and maxillofacial surgery, the use of CDS is limited to a few articles in the field of head and neck surgery [8,9,10,11]. To our knowledge, this is the first time to use CDS to assess complications in orthognathic surgery.

This study was conducted with a retrospective design and therefore results are limited by the reports in the medical records. A prospective trial systematically examining patients could overcome these uncertainties. These studies should include patients’ questionnaires directed toward discomfort, pain, satisfaction, and monitoring of clinical outcome and complications.

Conclusion

It is essential for caregivers to fully inform a patient about a chosen treatment, including expected discomfort, pain, and frequently occurring complications. Although MMD with bone-borne distractors was found to be a relatively safe method to widen the mandible, complications did occur. Fortunately, most complications were mild, transient, and manageable, without the need for any reoperation. Future prospective studies on MMD including the use of tooth-borne distractors should clarify whether these cause less discomfort, pain, and fewer complications than the bone-borne devices.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not report any financial interest or potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Eric Farrell, PhD, for his comments that greatly improved readability of the manuscript.

References

- King, J.W.; Wallace, J.C.; Winter, D.L.; Niculescu, J.A. Long-term skeletal and dental stability of mandibular symphyseal distraction osteogenesis with a hybrid distractor. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2012, 141, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Santo, M., Jr.; Guerrero, C.A.; Buschang, P.H.; English, J.D.; Samchukov, M.L.; Bell, W.H. Long-term skeletal and dental effects of mandibular symphyseal distraction osteogenesis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2000, 118, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- von Bremen, J.; Schäfer, D.; Kater, W.; Ruf, S. Complications during mandibular midline distraction. Angle Orthod 2008, 78, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mommaerts, M.Y.; Spaey, Y.J.; Soares Correia, P.E.; Swennen, G.R. Morbidity related to transmandibular distraction osteogenesis for patients with developmental deformities. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2008, 36, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mommaerts, M.Y.; Polsbroek, R.; Santler, G.; Correia, P.E.; Abeloos, J.V.; Ali, N. Anterior transmandibular osteodistraction: Clinical and model observations. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2005, 33, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.A. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Gijt, J.P.; Vervoorn, K.; Wolvius, E.B.; Van der Wal, K.G.; Koudstaal, M.J. Mandibular midline distraction: A systematic review. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2012, 40, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Awad, M.I.; Palmer, F.L.; Kou, L.; et al. Individualized risk estimation for postoperative complications after surgery for oral cavity cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015, 141, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, A.J.; Nixon, I.; Papadopoulou, D.; Crichton, S. Can we predict which patients are likely to develop severe complications following reconstruction for osteoradionecrosis? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013, 51, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bras, L.; Peters, T.T.; Wedman, J.; et al. Predictive value of the Groningen Frailty Indicator for treatment outcomes in elderly patients after head and neck, or skin cancer surgery in a retrospective cohort. Clin Otolaryngol 2015, 40, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perisanidis, C.; Herberger, B.; Papadogeorgakis, N.; et al. Complications after free flap surgery: Do we need a standardized classification of surgical complications? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012, 50, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the author. The Author(s) 2017.