Bony reconstruction of the mandible after surgical resection results in improved rehabilitation and aesthetics. Free tissue transfer with bone has transformed reconstruction, particularly in patients who have received radiotherapy. However, there is a morbidity related to free tissue transfer as well as the potential risk of failure of free flaps. Free nonvascularized bone grafts have much lower morbidity. However, many surgeons feel that free bone grafts in any mandibular defect greater than 6.0 cm is prone to failure and thus will always use free flaps to reconstruct these defects.

Bone grafting is an essential technique in bone and joint surgery to repair and rebuild diseased bones or to treat fractures and cancers. The transplanted bone can either be a xenograft (bone from a different species), an allograft (bone from another person), or an autograft (bone from another part of the same individual receiving the graft). [

1] Bone grafts can be vascularized (free tissue transfer) or nonvascularized (free bone grafts).

Macewen was the first to use free bone grafts (nonvascularized bone) in 1877. [

2] The first attempt at free bone grafts in the mandible was completed by Skyoff. [

3] Free bone grafts were commonly used in the First World War for the treatment of injured soldiers.

There are many advantages and disadvantages published to favor the use of either free tissue transfer or free bone grafts. [

4] Schliephake et al. showed that nonvascularized bone grafts had improved contour and symmetry. [

5]

Additionally, nonvascularized bone grafts have greater remodeling in comparison to vascularized bone grafts. [

6] The recipient surgical bed must be vascular and not damaged by radiotherapy for the successful transplantation of a free bone graft.

A direct correlation between the length of the free non-vascularized bone graft and its success is often quoted. The 6-cm rule has been popularized by several authors. [

7]

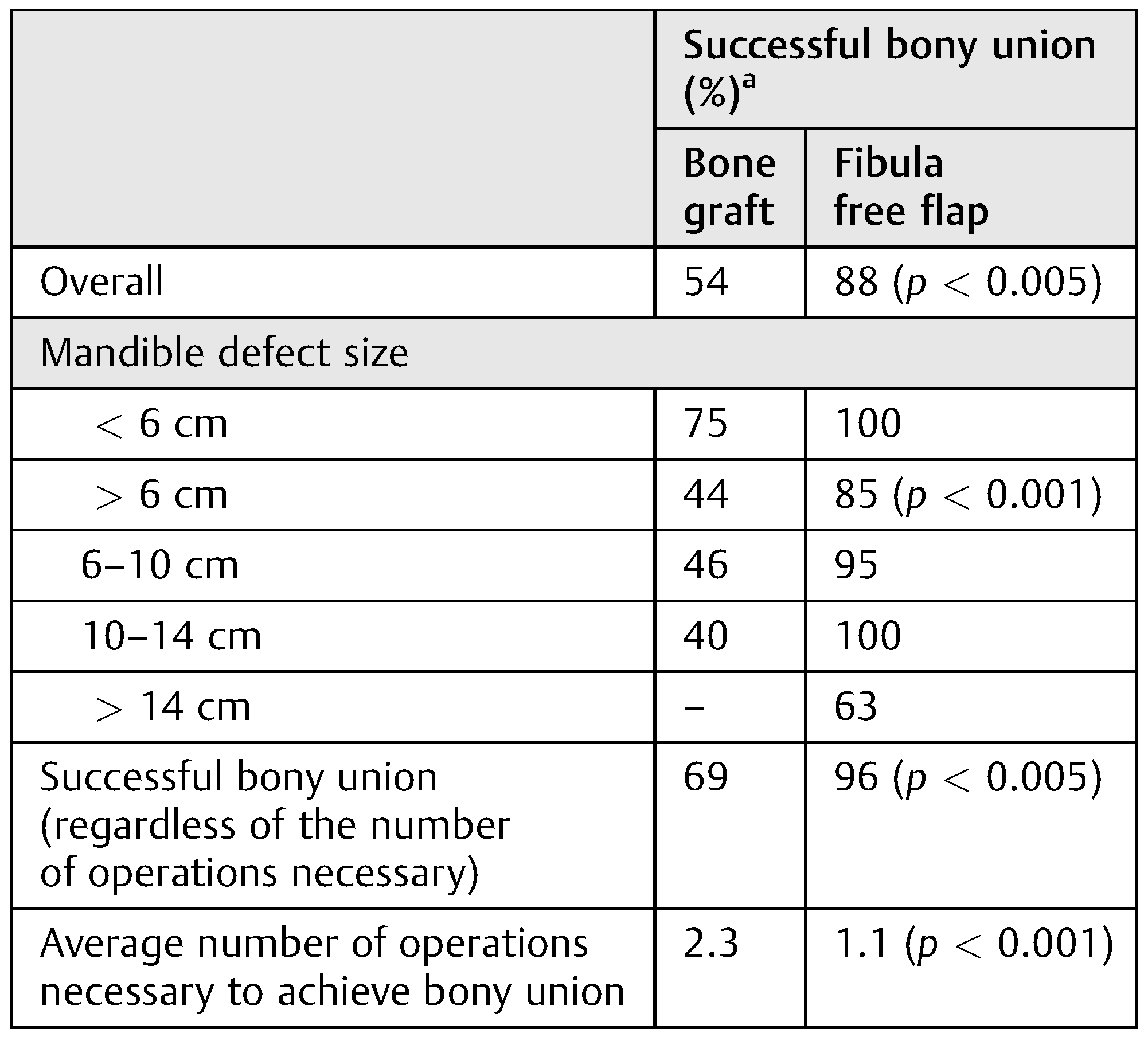

Pogrel et al. compared the differences in the use of vascularized and nonvascularized (free) bone grafts for reconstruction of the mandible. They found that the failure rate was greater in the nonvascularized bone grafts (24% failure rates) compared with vascularized bone grafts (5% failure rate); see

Table 1. They suggested that there was an increasing failure rate with an increasing length of the bone graft. He suggested that for defects greater than 6.0 cm, free bone grafting was contraindicated and a vascularized bony flap should be used. [

7]

Pogrel et al.’s study is often quoted as the reason for a free flap being required to reconstruct any defect greater than 6.0 cm in length.

In Birmingham and Florida, free bone grafts (nonvascularized bone) have been used for mandibular defects greater than 6 cm with good results.

This seemed to contradict the literature and general surgical practice.

The aim of this study was to review all patients who had free nonvascularized bone grafts for the reconstruction of mandibular defects > 6.0 cm in Birmingham, UK, and Florida, the United States.

Any such patients were then assessed for the following criteria:

Presenting pathology.

If the resection and the reconstruction of the mandible was staged.

Length of the free bone graft.

Height of the free bone graft.

Length of follow-up.

Complications.

If implant rehabilitation was performed.

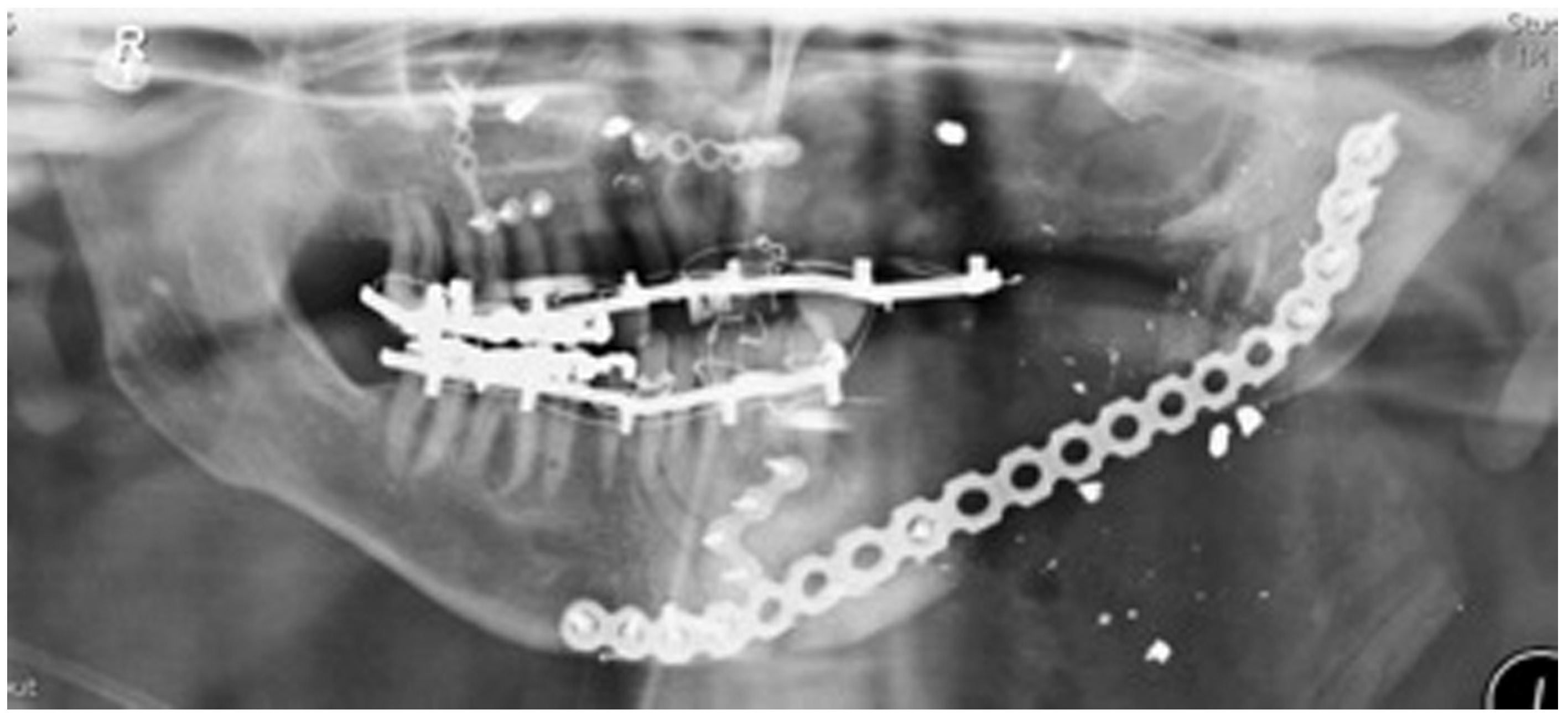

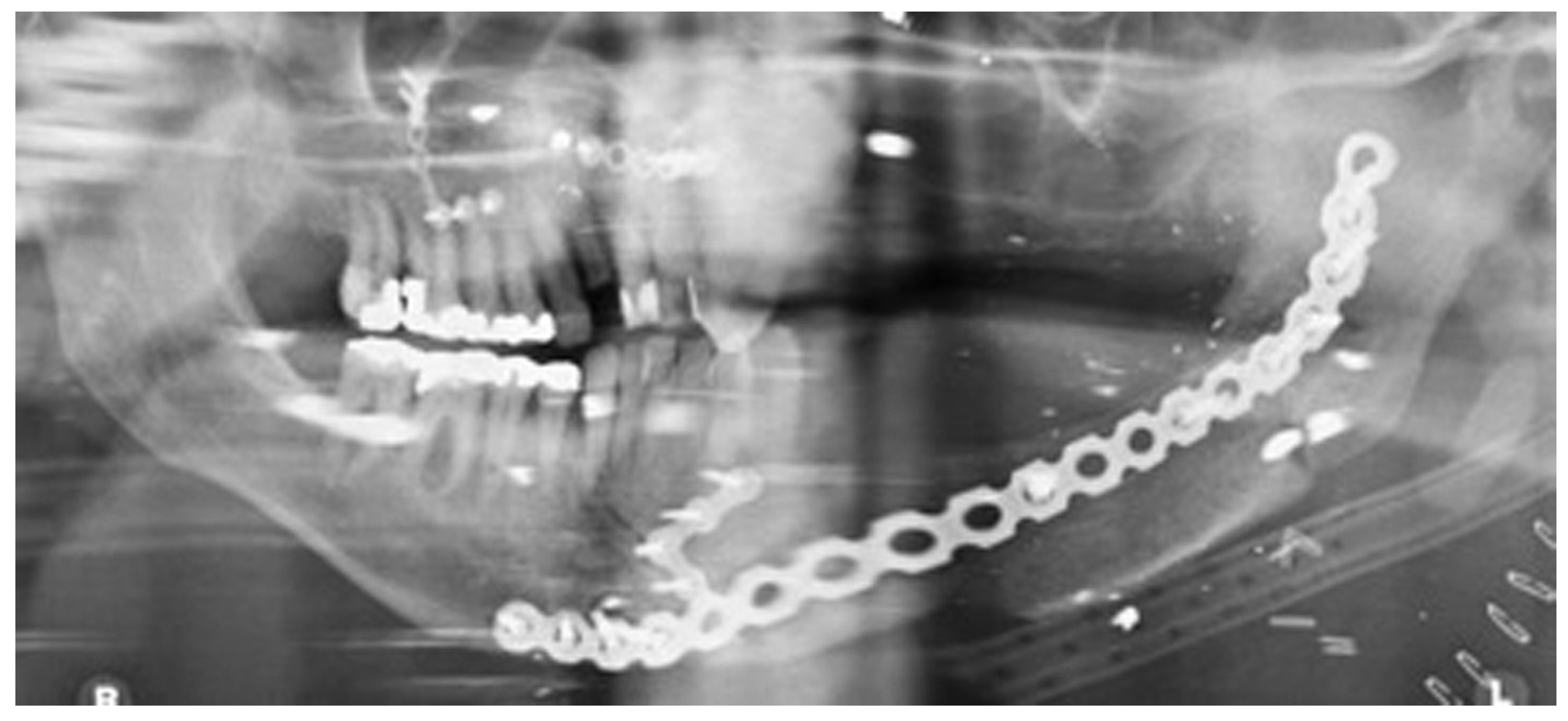

Staged reconstruction was defined as when the reconstruction with the free bone graft was performed as a secondary procedure. This secondary procedure was only performed when the oral mucosa had healed intraorally, sealing the mouth from the defect and the neck. A loadbearing locking mandibular plate was used to maintain the three-dimensional position of the bone and thus the occlusion (see

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

Pain and discomfort on walking were all thought to be standard side effects of surgery. Only complications related to the recipient site were assessed in this study.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective study. All patients who underwent free bone grafts for mandibular reconstruction at the two hospitals were identified using operating room logbooks. The length and height of the bone grafts were then measured using standard radiographs taken immediately after the surgery. The patient’s clinical notes were then used to review the other criteria required in the study.

Results

Eight patients had undergone free bone grafts in Birmingham and six patients at Florida for mandibular defects greater than 6.0 cm. See

Appendix 1 for results.

A variety of pathologies were responsible for the segmental mandibular defects. Ten defects were due to locally invasive tumors (nine ameloblastomas and one calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor). The remaining patients were due to segmental mandibular defects caused by gunshot wounds or osteoradionecrosis. The majority of these were in Florida.

All the reconstructions in our study were staged. The average length of the free bone grafts was 6.7 cm (range: 6.0–7.1 cm) and the average height of the free bone grafts was 2.3 cm (range: 1.0–3.2 cm). The follow-up period was between 6 and 108 months (average 30 months). Twelve patients had no complications at the recipient site and two patients had minor wound breakdown extraorally, which resolved with antibiotics. One bone graft was lost due to infection. In Birmingham, two patients had been dentally rehabilitated with implants. Another four patients have been scanned and are awaiting dental implant placement. No patient in Florida was dentally rehabilitated with dental implants.

Discussion

Previous literature suggests that free bone grafts greater than 6.0 cm are more likely to fail; thus, surgeons worldwide tend to treat these patients with free composite flaps. Free tissue transfer subjects patients to longer operations with potentially greater complications and much greater cost. The average hospital stay for a patient who undergoes a free flap is 14 days and that for a patient who undergoes a free bone graft is 3 days.

Radiotherapy is a known contraindication to free bone grafts. Surgeons in Florida and Birmingham had collaborated to treat patients who had not had radiotherapy or were likely to receive radiotherapy and had segmental defects greater than 6.0 cm with free bone grafts.

The surgeons felt that contamination with saliva and oral bacteria was the reason for failure of the bone grafts rather than the length of the free bone grafts. Thus, they staged the surgery and only proceeded with the free bone grafts once an oral seal had been achieved.

The other advantage of staging the resection of the tumor and reconstruction was that the resections margins can be assessed and a further margin can be taken, if required, prior to reconstruction.

The three-dimensional shape and position of the mandibular fragments was maintained by a strong locking plate, while the oral mucosa healed and the pathology was awaited. The same plate was then subsequently used to secure the free bone graft.

There was no incidence of plate exposure. This technique resulted in a low complication rate. Only one patient had a complication at the recipient site (mandible). The patient had developed a small dehiscence that resolved with a course of antibiotics. Although only two patients of the study group had been dentally rehabilitated, four other patients were awaiting dental implants. Insurance companies in the United States do not fund dental implants and therefore implant-based rehabilitation was rare in Florida. In Birmingham, implant-based rehabilitation is available on the National Health Service, and the unit aims to implant rehabilitate most patients.

In this study, the Birmingham/Florida results prove that bone grafts greater than 6.0 cm can be safely performed to reconstruct mandibular segmental defects in patients who have not received radiotherapy.

This study contradicts previous published literature. Segmental defects of the mandible greater than 6.0 cm can be safely reconstructed using free bone grafts with few complications and morbidity. It is not the length of the bone graft that is important but staging the reconstruction so that an oral seal is achieved prior to the bone grafting. The free bone grafts achieve good bony union and appear to be able to carry dental implants.