Abstract

The primary objective of the current study was to determine how job satisfaction effects the job performance of sugar industrial workers in Bangladesh. Moreover, this study examined the level of job satisfaction of employees in Bangladesh’s sugar industrial estate. In this quantitative study, respondents filled out a pre-structured questionnaire. The stratified random sampling approach was used to select 300 respondents from five sugar mills in the sugar industry. Job Performance Indicator (JPI), an 8-item self-rated performance scale, was used to assess job performance, and job satisfaction was measured using the JSI (Job Satisfaction Index). A regression analysis was performed using SPSS software for this study. Initially, reliability statistics were calculated for both scales in order to assess their relevance. The study’s findings showed a strong relationship between employee job satisfaction and job performance. The survey also showed that, compared to respondents’ personal characteristics, job-related factors had a greater impact on job performance. Furthermore, based on the findings of the study, job satisfaction among sugar sector workers in Bangladesh does not significantly differ by qualifications or age. In addition, the study found that foremen had a greater knowledge of the worksite than workers with less experience. However, the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant. There is strong evidence that employee satisfaction varies based on employee category. To improve job satisfaction and performance, the results and findings will be useful for the government, policymakers, and personnel departments of Bangladesh’s sugar mills. To make organizational decisions and policies about job satisfaction and job performance, it can be used to measure job satisfaction and the impact of job performance.

1. Introduction

Job satisfaction is the positive attitude of the employees towards the work [1], whereas job performance is the skill of an employee to work, and job performance determines whether or not a person does a good job [2]. Although job satisfaction and job performance are different things, there is a deep connection between them. The main goal of modern management and every organization of the present time is to influence their high job performance by ensuring maximum employee satisfaction [3]. Every organization needs a team of satisfied ‘workforce’ as well as high performers who are able to significantly accelerate productivity [4]. There is a widespread belief that an organization’s total productivity and success are dependent on employees’ efficient and effective performance [5] and that improved performance is dependent on employees’ job satisfaction [6]. There are numerous facets of job satisfaction, such as job-related and personal characteristics, that influence job satisfaction both directly and indirectly, and have a substantial impact on job performance and productivity [7]. Employee job performance is influenced by a variety of elements at work. It is described as the method of carrying out job tasks in accordance with the job description. Performance is the art of completing a task within predetermined parameters. Enhancing employee job satisfaction is one of the strategies to improve employee performance [8]. Employee work satisfaction is a favorable emotion that occurs when a person’s job performance is praised [9]. Employees who are content with their jobs are thought to perform better than those who are dissatisfied with their jobs [10]. In other words, if people are happy with their jobs, they will make an attempt to contribute some innovation and originality to the company through good performance, which will lead to significant market breakthroughs [11]. Job satisfaction, according to Omar, Rafie and Selo [12], is solitary of the strongest indicators of job performance. Job satisfaction affects job performance in both direct and indirect ways [13]. Job contentment has a favorable and considerable impact on job performance [4]. Previous research has shown that when an individual is satisfied, they will operate at their highest level to help the company meet its goals [14]. High-satisfied employees are more productive, devoted, and content in their jobs [15]. In order to enhance performance, it is necessary to increase job satisfaction. Performance expectations are one goal that a firm utilizes while reviewing its work [16]. An employee who is conscientious about their work will like their job and want to improve the company’s success by acting as a good performer [17]. Employee performance that is positive will lead to the organizational success; on the other hand, low employee performance will lead to organizational failure [18]. When a new employee is a perfect match for a position that the organization needs filling and enhances performance in that role [19], it can be a win–win situation. There is a direct correlation between job satisfaction and performance when a person is in the correct employment [20]. Employees are more committed, satisfied, and motivated, and their total performance is better [21]. Job performance is a measure of one’s wish to be consistent with one’s perceived level of involvement or significant contribution at work that is affected by high job satisfaction [22].

In this age of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the need for a well-equipped efficient workforce to adapt to the changing organizational behavior and objectives in a competitive business environment is paramount. Rapid changes over time include the scope of management, the administrative structure, the type of leadership, the surrounding environment and the type of demand. Professional managers are urged to choose the best performers to meet the challenges of the 4.0 technology of the 21st century. However, to ensure job performance, they need to have high job satisfaction resources and components. Many researchers believe that if the workforce is highly satisfied then the result will be good job performance. High job satisfaction is not only guaranteed but the working class will also be committed to the organization in the long run, productivity will increase, labor turnover will decrease, accident rates will go down and, above all, performance will reach desired levels. A worker tries their best to reach a satisfactory level of performance only when they enjoy all the facilities of the organization and thinks that the level of satisfaction is at the desired level. The influences of job facets [23] are the most prevalent of all the factors that affect job satisfaction. Personal factors, on the other hand, have an impact on job satisfaction. Simultaneously, the effects of job factors and personal factors on job performance are strongly related to job performance. Currently, research is being conducted to determine how job factors and personal factors influence satisfaction and job performance.

Workers in the sugar industry in Bangladesh are particularly concerned about job satisfaction. Job-related factors, including pay, promotion, job security, job status, working environment, open communication, relation with colleagues, participation in decision making, autonomy in work, behavior of boss and recognition for good work, have called into question the satisfaction rate of workers in the sugar industry. There have not been many studies on Bangladeshi sugar sector workers. Moreover, most of the research work that has been conducted is related to manufacturing and engineering. It goes without saying that there is no research on sugar industry workers, especially on the job satisfaction and job performance of workers in the sugar industry. Many studies have been conducted on job satisfaction and job performance in the Western world. However, the number of studies on sugar industrial workers’ job performance and job satisfaction is insufficient. This study’s distinctiveness comes from the fact that it is the first one of its kind to examine the performance and job satisfaction of workers in Bangladesh’s sugar sector. Since there is insufficient research on job satisfaction and job performance in Bangladesh as well as in the world, the current research is entitled “Effect of Job Satisfaction on Job performance of Sugar Industrial Workers in Bangladesh”, and that is why the present research is really commendable. Therefore, the primary goal of this study is to investigate the connection between employees’ job satisfaction and job performance, particularly in Bangladesh’s sugar industry.

The paper is organized into the following sections: Section 2 reviews the pertinent erstwhile literature to establish a research framework and hypotheses. The methodology and procedures are described in Section 3; contents are operationalization of constructs, and survey administration and sample. The analysis and empirical results are presented in Section 4 that concentrates on statistical analysis and outcomes. The effects of the study are examined in the discussion section in relation to earlier research. This section also examines the theoretical and practical ramifications of the study. In the final section, there are references and conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Job Satisfaction, Demographic Factors and Job Facets

Job satisfaction is linked to how well the individual pays attention to, reflects on, and engages with their tasks and responsibilities. Job satisfaction is as an emotive variable resulting from an appraisal of a person’s work experience [24]. Employment satisfaction expresses a person’s level of contentment with their job [25]. Furthermore, job satisfaction at work is a symptom of joyful psychological states, which results in great performance [26]. The state of peace and relaxation, which is a determinant of a worker’s job satisfaction, may be acquired in a variety of methods at various levels [27]. One of the numerous components of enjoying one’s work and having a positive emotional response is job satisfaction. Workplace satisfaction is nothing more than acquiring tranquility. If a person really states, “I am satisfied with my job”, they are referring to a combination of environmental, physiological, and cognitive factors [28]. The appeal of a job determines work happiness [29]. When a person satisfies expectations at work, they experience job satisfaction. Additionally, a happy mental state that results in high-quality job roles is what leads to job satisfaction [30]. When someone works in a setting like this and fulfills expectations, they are satisfied with their work. Job satisfaction is the result of a person’s desire for their work and what they actually receive from it. Moreover, the happy mental state that meets work criteria contributes to job satisfaction [31]. Job satisfaction is an excellent indicator of responsibility since it is based on a character assessment [32]. People who are content and joyful in their jobs perform better than those who are not [33]. Emotional factors that affect job satisfaction include pleasure, happiness, passion, enthusiasm, and love [34]. One of the workplace behaviors is job satisfaction, which is a sense of fulfillment derived from job experience [35]. Job satisfaction was described by Nduati and Wanyoike [36] as having positive and emotional views regarding one’s work. Job satisfaction, according to Abdulkhaliq and Mohammadali [37], is one of the elements of a professional viewpoint and might be useful in keeping managing employees. Shahnawaz Adil [38] asserts that employee work satisfaction affects their behavior and can raise the standard of output in industrial facilities. As stated by Locke [9], “a happy or good emotional state arising from the evaluation of one’s job and job experiences” is what is meant by job satisfaction. Job satisfaction is the “Ultimate condition of emotion”, according to Siahaan [39]. Depending on whether or not needs are met, feelings may be either pleasant or negative. A good attitude toward a job results from examining and evaluating its aspects [40]. People with good attitudes about their jobs report higher levels of work satisfaction, whereas those with negative attitudes report lower levels of job satisfaction. The attitudes and sentiments that people have of their job are referred to as job satisfaction by Hudson et al. [41].

Numerous studies show a substantial relationship between job satisfaction, elements connected to the job, and demographic factors [42,43,44,45,46]. Lange [47] discovered that a demographics’ impact on job satisfaction was considerably significant.

According to Abdulkhaliq and Mohammadali [37], having children, a marriage, and academic credentials can all affect work satisfaction. Nguyen and Duong [18] found that there is no discernible relationship between satisfaction and any of the control factors, such as age, gender, or educational attainment. People of all ages are mostly content, according to Islam, Kamruzzaman, and Gazi [48], although this is not statistically significant. Mesurado et al. [43] revealed that a demographic’s effect on job satisfaction is considerably good. Cavanagh et al. [49] found that work happiness was positively connected with respondents’ age and experience, and gender differences had no observable impact on job satisfaction. Personal traits, including personality, culture, and demographic traits, have little bearing on work satisfaction, according to Islam and Akter [50]. Abuhashesh, Al-Dmourand and Masa’deh [51] found that employees’ pleasure and concern for their salary and status outweigh all other considerations (demographic factors). Age and experience had a significant impact on workplace happiness, according to studies by Anastasiou and Garametsi [52], while other personal criteria, such as gender, marital status, and designation, had no discernible beneficial effect. Numerous empirical research has demonstrated the impact of elements connected to the work on job satisfaction [53].

Kim and Cho [54] discovered a link between the working environment and workers’ job satisfaction. Compensation has a big impact on work satisfaction [55]. Another study discovered that job security is the most important driver of job happiness [56]. According to Tran and Tran [42], the key job satisfaction factors are interpersonal relationships, work itself, and acknowledgment. Yusuf [57] exposed that some employment characteristics were positively associated to overall job satisfaction. According to Kampf and Hernández [58], a number of studies have looked at demographic parameters to predict labor satisfaction; however, Baeza et al. [59] discovered that, with the exception of gender, there is no substantial association among demographic characteristics and job satisfaction. According to Sánchez and Puente [60], human characteristics, such as personality, culture, and demographic parameters, have little effect on work satisfaction. According to Joshi [61], there is a strong and statistically significant link between job satisfaction and the work environment. Employee job satisfaction varies according to age group [62]. According to the investigation by Omar et al. [12] on the connection among both job satisfaction and job environment, people value their employment more when they work in a nice atmosphere. Chan [63] found a strong correlation between pay, supervision, rewording, operational procedure, equitable promotion, other financial facilities, opportunities for open communication, and interpersonal interactions amongst employees.

Employees that are happy with their jobs typically perform well and are very loyal to the company. As a result, maintaining a positive connection between employees and employment is essential for a successful firm [5]. We are aware that respect for industry employees is the foundation of happiness. Job-related variables often take center stage as a way to raise the dignity and contentment of the workforce. Industrial disputes are being caused by employees’ resentment, anger, and protestations to the job satisfaction components mostly related to job related factors in the workplace. Along with the indications of job-related aspects that influence job satisfaction, demographic factors, including age, experience, education, and nuptial status, have a big sway on job satisfaction. When the elements of their workplace meet their demands, employees exhibit better levels of job satisfaction, which leads to excellent performance, reduced inclinations to leave, lower absenteeism rates, and lower accident rates. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1:

There is no significant difference of job satisfaction among the levels of employees.

Hypothesis 2:

There is no significant influence of the personal factors on the overall job satisfaction of the respondents.

Hypothesis 3:

There is no significant influence of the specific job-related factors on the overall job satisfaction of the respondents.

2.2. Job Satisfaction and Job Performance

Organizational management has always faced significant challenges with regard to employee job performance [64]. A successful organization depends on how well its workers perform on the job and accomplish its goals [65]. When analyzing organizational behavior, which eventually results in organizational success, it is critical to consider the link between work satisfaction and job performance [66,67]. This is because highly pleased employees perform better than their unhappy coworkers [68]. Several factors may influence the link between work satisfaction and performance, which is a relationship between two concepts that are interrelated [69]. The impact of work satisfaction on performance has been the subject of much research [64,68,70]. Sánchez-Beaskoetxea and García [71] and Kumar [72] observed a linkage between work happiness and job performance standards. Work satisfaction may have a favorable influence on performance since workforces who are pleased through their demands have enhanced performance. Omar et al. [12] interviewed 130 polytechnic staff in Malaysia regarding their job happiness and performance. Their findings demonstrated that work satisfaction has a considerable and favorable impact on employees’ job performance. Okolocha et al. [73] revealed there is a definite significant relationship between employee job satisfaction and performance in both directions. Responsibility and career progression have a favorable and substantial influence on the work performance of academic staff at public institutions in south-east Nigeria observed by Okolocha et al. [73]. Okechukwu [74] conducted a study among Malaysian academic and administrative workers. The study’s population consisted of 81 academic and administrative staff respondents. To assess the link between independent and dependent variables, Pearson moment correlation was utilized. According to empirical results, training and development have a statistically significant association with job performance and job satisfaction among employees. Oravee, Zayum, and Kokona [75] investigated the influence of intrinsic and extrinsic incentives on employee performance. Primary and secondary data were employed in the investigation. This study consisted of 51 subordinates and 28 supervisors, and the study found that job satisfaction is related to employee performance because exultant employees are more likely to be concerned about the tasks at hand, work quickly, produce error- and omission-free work, be willing to take on more responsibility, and perform at their best. Employee job satisfaction, according to Agustina et al. [76], is a key factor in organizational performance. Some of these studies’ conclusions showed a high correlation between worker job satisfaction and job performance [77]. Bayona et al. [7] revealed that employees in Jordan are more focused on their job satisfaction than the pay that affects their performance. Job happiness has been found by Wang and Chen [78] to improve job performance. Rohmawati, Maya, and Robbani [79] also carried out research with the aim of examining the relationship between job satisfaction and sales staff performance with adaptive selling practices. The study showed that there is a robust correlation between performance of sales personnel and job satisfaction.

Rachman [80] studied the job performance and job satisfaction of 43 government employees in Indonesia and investigated the effects of organizational commitment and personnel performance on job satisfaction. They discovered that organizational commitment and job satisfaction have a detrimental impact on an employee’s performance at work. Wang and Chen [78] discovered that job satisfaction and the workplace environment can positively affect employees’ job performance and make job satisfaction a significant factor that workers can accept in achieving their high performance. Additionally, Hassan et al. [81] attempted to observe the rapport between management employees and public organizational performance with a focus on job satisfaction as a reliable mediating variable. They noticed a positive significant correlation between them. Gün et al. [82] concurred that there is an irrefutable link between employee performance and job satisfaction. Arif, Rivai, and Yulihasri [83] demonstrated that there is a correlation between job satisfaction and a worker’s job performance in terms of income, security, and the incentive system. One of the many elements that affect employee job performance, according to Bjaalid et al. [84], is work satisfaction. In contrast to displeased workers who are viewed as a burden for any organization, pleased employees perform well and contribute to the overall goals and success of an organization [85]. Alrazehi et al. [86] found that the job satisfaction has an influence on nurses’ performance in hospitals. In research by Khan et al. [87] on the effect of demographic characteristics on job performance from Pakistan, it was discovered that the majority of the variables, including job satisfaction, had a substantial influence on job performance. Job satisfaction and emotional commitment were found to have an impact on job performance by Yandi et al. [88].

On the other hand, several studies hold opposing views on this. According to Way et al. [89], job satisfaction has no bearing on how well a task is performed and does not impact job performance. Other causal factors influence the association between job satisfaction and performance. The theoretical and practical repercussions of a relationship between false pleasure and performance are substantial. The preponderance of laypeople feels that there is a link between work happiness and job performance. Consequently, we postulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4:

Employee performance in the sugar industry is impacted by their level of work satisfaction.

3. Research Methodology and Procedures

3.1. Operationalization of Constructs

The Bengali version of the 18-item job satisfaction measure was utilized to gauge workers’ job happiness [90]. There are nine positive and nine negative items on this eighteen item scale (Table 1). For a positive item, a score of 1 means “strongly disagree”, a score of 2 “disagree”, and a score of 3 means “undecided”, scores 4 and 5 are “agree” and “strongly agree”, respectively. The scoring was performed in reverse for negative items. The overall score on the scale for a particular person was the sum of the scores on all elements. Eighteen (18) is the lowest score, ninety (90) is the highest, and forty-five (45) is the neutral point. A higher score reflects more work satisfaction. This scale has a very high degree of dependability. According to Cronbach, Fornell and Larcker, the Brayfield–Rothe scale’s [91] reliability and validity values are 0.87 and 0.93, respectively.

Table 1.

Overview of job satisfaction items of Brayfield and Rothe’s Index of Job Satisfaction (IJS).

The 18 items from Brayfield and Rothe’s [91] Index of Job Satisfaction (IJS) were operationalized to measure job satisfaction, the study’s independent variable. Scale creation began as a class assignment for a group of personnel psychology students who were participants in an American army specialized training program [92]. Any item that made reference to particular work features was removed from the scale since it was desirable to have a broad measure of job satisfaction. A five-point Likert scale with five categories—strongly agree to strongly disagree and a neutral response in the middle—was used. Responses can range from 1 (very satisfied) to 5 (strongly disagree) (very dissatisfied).

Furthermore, a questionnaire was created to gauge satisfaction with 11 particular areas of the work. Khaleque and Choudhury [93] originated that questionnaire to measure satisfaction with 11 particular factors of the employment (MSF). Several researchers have suggested that these factors, which were included in the questionnaire to cover various areas of job satisfaction that have an impact on employee behavior [9,26]. The responders would check either a “Yes” or a “No” response to express their satisfaction or disagreement with each of these specific features (Table 2).

Table 2.

A description of the MSF work satisfaction elements [93].

Regarding the performance of the workers, the immediate boss of each respondent was requested to give their rating of the performance of each respondent in terms of one hundred. Here, subjective judgment was taken because of the absence of objective criterion to measure the performance of garment supervisors. Performance ratings were taken in a separate sheet from the immediate boss, after filling the questionnaire from the subjects. Performance of the worker denotes the actual units produced by the individual worker expressed in terms of one hundred set by the management of the concerned sugar industrial workers. The researcher created a self-made performance evaluation form to assess employee performance while taking into account the typical scale design process described in the psychometric literature. The final draft contained of 8 factors, including quality of work, quantity of work, job knowledge, initiative, creativeness, cooperativeness, undependability, and personal development. Performance matters were graded with a 5-point Likert scale. It has also entailed job facets data sheets. Job performance was measured with an 8-item self-rated performance scale developed by Valianawaty and Sutanto [94], namely the Job Performance Indicator (JPI) in adaptation reported by Inayat and Khan [4] and Abramis [95]. This scale asked respondents to think about their previous week at work and rate how well they performed on 8 tasks (Table 3).

Table 3.

An overview of the JPI’s job performance items.

The primary data were collected by giving out questionnaires to employees in production units of sugar mills in Bangladesh. The present study focuses effects of job satisfaction on job performance, testing the study’s hypothesis, as well as the validity and reliability of the questionnaire results, using the analytic software. At first, official consent was obtained from the leaders of the organizations to grant the researcher access to their company employees.

3.2. Survey Administration and Sample

The present study is concerned with effects of job satisfaction on job performance of workers in the sugar industry in Bangladesh. The approaches adopted are basically analytical and interpretive in nature, considering the objective of the study and a review of literature. It was decided to use qualitative and quantitative descriptive methods of analysis related to overall job satisfaction and job performance of workers in the sugar industry in Bangladesh. The universe of the study comprised of 5935 (permanent workers 2893, seasonal workers 2355 and no work no pay workers 687) workers working in the sugar industry in Bangladesh. They are all production workers. The population of the study was 1260 employees working in 5 selected sugar mills. Workers were chosen from the sugar mills in Bangladesh using proportionate stratified random sampling. A total of 300 participants comprised the study’s sample, which comprises 23.81 percent of the population of the study. Sample size calculated by using the formula, which is given by Yamane [96]. The list of total sugar mills was collected from Bangladesh Sugar and Food Industries Corporation (BSFIC), which is under the public sector. The researchers selected five (5) major sugar mills to investigate for the aim of the study. These industrial estates are located in the neighboring districts of Rajshahi, Kushtia, Jhenaidah, Chuadanga, and Faridpur in Bangladesh. The five public sector sugar mills’ lists are chosen at random, particularly using the lottery method. The distribution of the total selected sample according to type of organizations and level of employees is show in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sample distribution according to sugar mills and level of employees (n = 300).

Table 4 demonstrates that 66.67 percent of respondents were workers, and the remaining 33.3 percent were foreman. Furthermore, 13.33 percent of the respondents were working as permanent workers in every selected sugar mill and the remaining 6.7 percent were working as foremen in every selected sugar mill, and a total of 20 percent of respondents were collected from each selected sugar mill.

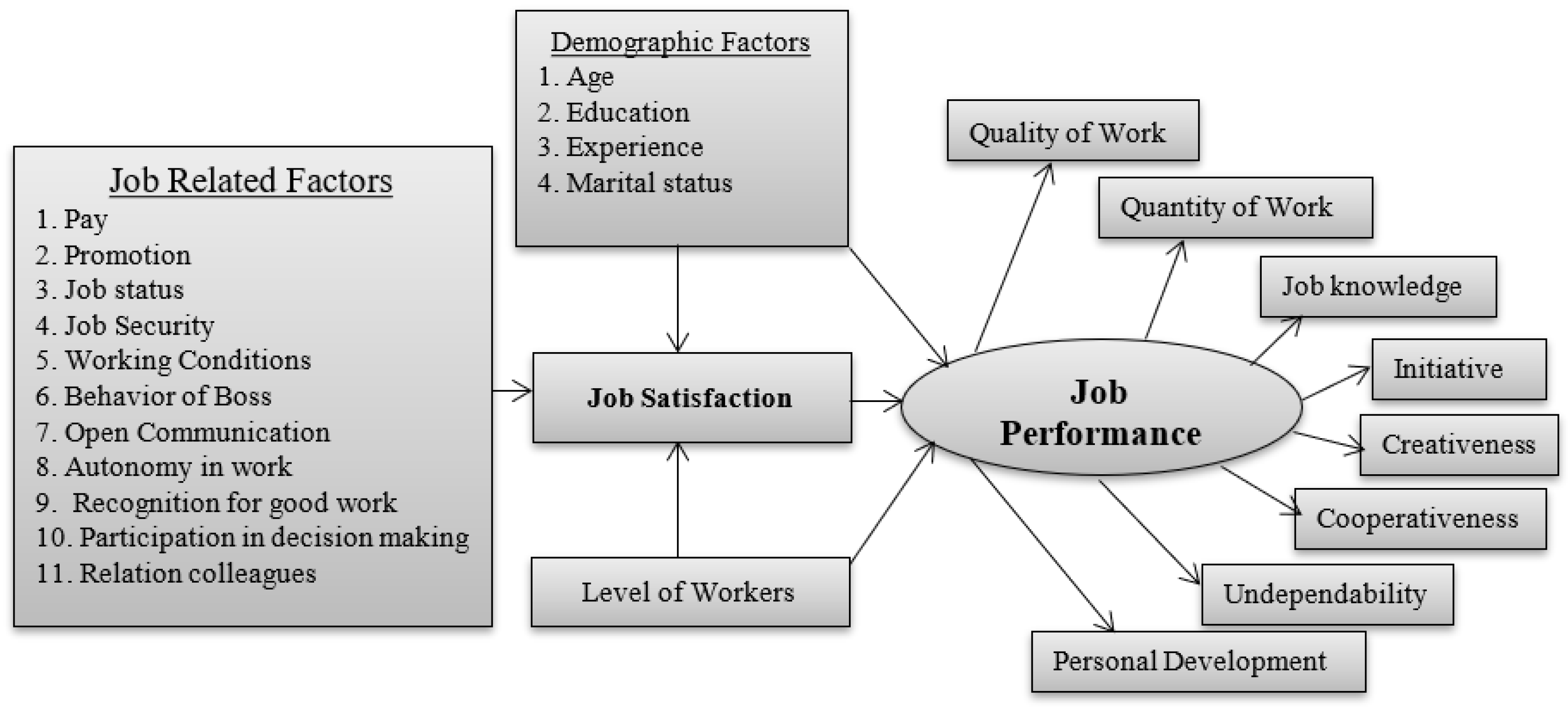

The researcher gathered the data personally between October 2021 and June 2022. When responders encountered an issue, they were given the required clarifications. Employees with fewer than two years of experience were not eligible. The interviews were conducted during working hours, lunch breaks, and after hours. Each individual needed roughly 30–40 min to complete the relevant information for the questionnaire. Using the literature review as a foundation, this work develops a research framework (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research framework.

According to Hair Jr et al. [97], the Cronbach’s Alpha value needs to be higher than 0.6. The composite’s dependability must therefore be higher than 0.7. All variables had Cronbach’s Alpha values and composite reliability in accordance with predetermined norms, according to the information in Table 5. Furthermore, the results for the convergent validity may be accepted because Table 5 shows that all AVE values for all constructs are more than 0.5. The square root value of the AVE value, sometimes referred to as the diagonal, must be higher than the value of the diagonal number for discriminant validity [98]. The value of in diagonals is always higher than off diagonals, making the discriminant validity test valid [99].

Table 5.

Reliability and validity test.

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Demographic Profile

Table 6 reveals that the highest percentage (33.67%) of the respondents was from the 55 and above age range. On the other hand, the second highest percentage (26.33%) of the respondents was from the 45–55 age group. It is exposed that all (100%) foremen were from the 55–65 age group. On the other hand, among the workers the highest percentage (39.5%) was from the 45–55 age group. Additionally, it was noted that the foremen’s average age (56.56) was greater than the workers’ (39.06). The findings also imply that the foremen’s mean age was much higher than the workers. Thus, it is clear that in sugar mills of Bangladesh most of the foremen are aged and workers are relatively younger. Table 6 also shows that 8.33% of the respondents were fully illiterate, and the highest number of the respondents 152 (35.71%) were from class 6–9. Additionally, it was found that just 5% of the workers and 15% of the foremen were literate. Foremen made up 42% of the VI–IX class schooling, while workers made up 55% of the class six to nine schooling. The table also reveals that workers’ average educational attainment was greater (3.29) than foremen’s (2.68). These findings also suggest that workers had much greater levels of education than foremen—one to five years of schooling.

Table 6.

Demographic information of the respondents.

Table 6 also shows that the highest percentage (36.67%) of the respondents was from the 30–40 years’ experience group. On the other hand, the second highest percentage (20.33%) of the respondents were from the 20–30 experience groups. the highest numbers of foremen (80%) were from the 30–40 years of experience group and the highest numbers of workers (43%) were from the 0–10 years of experience group. According to Table 7, which shows that the average experience of foremen is 35.21 years and the average experience of workers is 15.64 years, respectively, there is a substantial difference between the two. Again, Table 6 shows that 66.67 percent of respondents were workers, and the remaining 33.33 percent were foremen. Further, 91.33% of respondents were married and only 8.67% respondents were unmarried, and a total of 20 percent of respondents were collected from each selected sugar mills.

Table 7.

Comparing the means of age and experience according to work satisfaction using descriptive statistics.

4.2. Statistical Evaluation and Findings

Employees’ personal factors affect the level of satisfaction. Respondents are categorized in two ways—workers and foremen. Respondents are also classified as married and unmarried. This study considered a few personal factors, i.e., age, education, experience and marital status. The level of job satisfaction according to personal factors is shown below.

The descriptive data and differences in averages for age and experience between the satisfied and unsatisfied groups are shown in Table 7. It demonstrates the significance of the t-value for the satisfied and unsatisfied age groups. This shows a substantial variance in mean job satisfaction between the satisfied and unsatisfied age groups [t(298, 300)2.008, p > 0.05]. Additionally, the mean ages of contented and unsatisfied foremen and workers varied significantly. However, this difference was shown to be statistically significant [t(298,300)17.392, p > 0.05]. Age is a significant factor, with the mean ages of the foreman and workers being 56.56 and 39.056 years, respectively [t(298,300)27.232, p > 0.01]. Table 7 also shows the foreman’s 35.21 years of working experience and the worker’s 15.64 years, which is considerably demonstrated in the table. Table 7 shows that foremen’s age and experience are substantially greater than workers’, and when comparing satisfied and unsatisfied employees based on experience, satisfied respondents were significantly more experienced than unsatisfied workers [t(298,300)1.71, p > 0.05].

Table 8 shows the satisfaction level of respondents based on education. Results show that most of the respondents are dissatisfied (67.33%) and had completed up to secondary education (SSC). On the other hand, only 22.33% respondents having HSC, Bachelor’s and above degrees, were identified as dissatisfied. The mean difference in job satisfaction scores across educational levels was not statistically significant. Respondents with an S.S.C. qualification had the highest mean job satisfaction score (69.21). The findings in Table 8 revealed that workers have much greater levels of education than foremen. Age means 56.56 and 39.056 years for foreman and employees, respectively, while education means 2.68 and 3.29 years for foreman and workers, which is noteworthy [t(298,300)−4.594, p > 0.01].

Table 8.

Satisfaction level and educational qualification.

It is observed from the above Table 9 that among the respondents, 44.33% of workers and 27.33% of foremen are found to be satisfied. Table 9 shows that there are no substantial distinction job satisfaction values of foremen and workers. The Z score is 0.815, indicating that the satisfaction of foremen and workers is not statistically significant. Table 9 also represents the mean score for foreman (68.93) and workers (68.01). Foremen reported somewhat greater levels of job satisfaction than workers, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 9.

Relationship between work satisfaction level and employee level.

Table 10 shows that 39.67 percent of married respondents are satisfied with their jobs, whereas 51.67 percent are dissatisfied with their occupations. Similarly, 44.33 percent of unmarried persons said they were satisfied with their jobs, while 22.34 percent said they were unsatisfied. Nonetheless, this distinction is determined to be substantial. The mean value for foreman and laborer is 78.02 and 69.33, respectively, according to Table 10. The job satisfaction level of foremen was greater than that of workers based on marital status, but because unmarried workers are more dissatisfied than married workers and this is significant, it is concluded that the employee’s marital status had a significant relationship with their job satisfaction [t(298,300)2.083, p > 0.05].

Table 10.

Level of job satisfaction in relation to marital status of employees.

Table 11 indicates that average overall satisfaction of the unsatisfied respondents was significantly greater than that of those who were satisfied with the specific aspects of job, except only three job factors, i.e., job status, behavior of boss and relationship with colleagues. The result indicates that overall job satisfaction differed significantly with satisfaction and dissatisfaction of the specific job factors.

Table 11.

Mean differences of job satisfaction according to the degree of satisfaction and dissatisfaction with some specific job factors (n = 300).

Table 11 displays the descriptive statistics for the aspects of the performance assessment process based on level of job satisfaction. The observed covariance matrices of the dependent variables were not found to be equal across groups, according to the results of the box’s test of equality of covariance matrices. For happy respondents, the mean pay score was 68.07 with SD = 7.94, whereas for unhappy respondents, the mean pay score was 69.31 with SD = 9.24. Similarly, unsatisfied employees scored the highest on participation in decision making, with a mean of 70.32.

To see the influence of job satisfaction on performance, the respondents were divided into two groups—high and low satisfaction groups. The respondents whose job satisfaction scores were below and above the median scores were termed as low and high satisfaction groups, respectively. Z-test was applied to compare the mean differences of the two groups and the results are shown in Table 12.

Table 12.

Mean differences of performance to the degree of job satisfaction of the respondents (n = 300).

It was observed from Table 12 that the mean differences of performance between the higher and lower satisfied groups were statistically significant. The results further indicate that the job performance was significantly higher among the higher satisfied group than that of the lower satisfied group.

Table 13 demonstrates the mean value of different factors affecting performance. The present study shows that all job-related factors have great influence on performance outcomes. Job related factors have found direct influence on job performance. The results found from Table 13 that the job performance outcomes (quality of work, quantity of work, job knowledge, initiative, creativeness, cooperativeness, undependability, personal development) are positively affected by job related factors.

Table 13.

Mean value of descriptive statistics.

In this study inter-correlations for some important variables (age, education, work experience, job satisfaction, and job performance) of all employees have been examined to see the degree and direction of correlation among those variables.

Table 14 exhibits that there was significant positive correlation between age, level of education and work experience and job satisfaction. It is also observed that there was substantial positive correlation among age, work experience and job performance, but there was no significant correlation between level of education and job performance. Finally, there is a significant positive correlation between level of job satisfaction and job performance.

Table 14.

Age, education, work experience, job satisfaction, and job performance are inter-correlated in the correlations matrix for all respondents in the category (n = 300).

The results in Table 15 show that there was positive significant correlation between job satisfaction and job performance. Positive significant correlation had been found among job satisfaction and promotion, job satisfaction and working conditions, job satisfaction and behavior of boss, job satisfaction and open communication, job satisfaction and autonomy in work, job satisfaction and recognition for good work, and job satisfaction and participation in decision making. On the other hand, there was significant positive correlation among job performance and all job-related factors, except job status, open communication, recognition for good work and relationship with colleagues.

Table 15.

Correlation matrix among dependent (job satisfaction and job performance) and independent (job related factors) variables (n = 300).

Table 16 shows that after adhering to the given statistical criteria, only seven of the independent variables (job related factors—pay, promotion, job security, working conditions, behavior of boss, autonomy in work, participation in decision making) were entered into the equation with the insertion of the independent variables (job related factors), the R, R2 and adjusted R2 increased.

Table 16.

Model summary of step-wise multiple regression: dependent variable job performance.

Table 16 indicates that pay, promotion, job security, working conditions, behavior of boss, autonomy in work, and participation in decision making were the best set of predictors of job performance. Each of these parameters brought about a significant change in adjusted R2, allowing the variance of those seven parameters to account for 42.9% of the variance in performance. Based on pay, model 1 explained 13% variance in job performance. Furthermore, together, pay and promotion, pay, promotion and job security, pay, promotion, job security, working conditions and behavior of boss, pay, promotion, job security, working conditions and behavior of boss, pay, promotion, job security, working conditions, behavior of boss and autonomy in work; pay, promotion, job security, working conditions, behavior of boss, autonomy in work, and participation in decision making indicates 21.3%, 28.3%, 31.0%, 34.7%, 38.8% and 82.9% variance in dependent variables of job performance, respectively.

5. Discussion

The following explanations are given with the support of the argumentation of hypotheses that were approved or disapproved of, drawn from the literature review and the findings of the current investigation.

According to the findings of this study, there is no substantial relationship between employees’ job satisfaction and their qualifications or ages. In contrast to the Yandi et al. [88] study, which found a positive link between qualification and work satisfaction, the current study found no such association. Alrazehi et al. [86] found an association between age and work satisfaction in their study. The results indicate that older workers (foremen—high age) seem to be more satisfied with their occupations than young employees (workers—low age), and that the satisfaction across the satisfied and unsatisfied age groups differs significantly. It also demonstrates how happy experienced workers were at work. When comparing satisfied and dissatisfied employees based on experience, satisfied respondents were considerably more experienced than unsatisfied employees [t(298,300)1.71, p > 0.05]. Table 7 shows that experience and age of foremen are higher than workers and more experienced employees (foremen) are happier than less experienced (workers), and it was statistically significant. Following the findings of Arif et al. [83], who found no statistically significant difference between marriage status and job satisfaction, the current study indicated that the employee’s marital status had a significant link with overall job satisfaction. The survey found that married employees are happier than single ones, and all foremen are married. The mean difference in work satisfaction scores across educational levels was not significant statistically. The educational quality of employees is much greater than foremen, which is significant. Satisfied foremen in the sugar business were higher than employees, indicating an affirmative correlation between individual job satisfaction and staff levels. The current study strongly confirms the findings of Khan et al. [87], who discovered that employee satisfaction levels fluctuate across various employee categories. Several studies have also found that older employees with more experience are more satisfied than younger employees with less experience. The findings of Table 7 show that the age category z-ratio was statistically significant. When other demographic factors, such as level of education, level of experience, and spousal status, are taken into account, there is a significant difference in the level of work satisfaction between workers and foremen (Table 8 and Table 10). Consequently, our null hypothesis (H2) is rejected for the entire variable regarding the personal aspect. Compared to workers, foremen reported slightly higher levels of job satisfaction in Table 10, but the difference was not statistically significant. Thus, the results confirmed the null hypothesis 1. Several researchers have found that age, experience and level of education have a considerable favorable influence on total job satisfaction [4,72,85,86], confirming the current study’s findings. According to current findings, workers in the sugar industry differ substantially in terms of job satisfaction, and in terms of education, experience, or marital status (Table 7, Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10). With age, job satisfaction rises; the more senior a person is, the more satisfied they are with their work. The findings are similar with prior findings [68,72]. Syamsudin et al. [100] discovered that highly educated employees were more satisfied, which supports the current study’s conclusions. All job-related factors, with the exception of employment position, are positively correlated with job satisfaction, according to Table 11’s findings, behavior of boss and relation with colleagues resulted in no statistically significant differences between satisfied and dissatisfied respondents. As a result, the current study’s findings most likely endorse the null hypothesis (H3). Arijanto [69] and Anis et al. [101] discovered similar findings. The current study also found that foremen were happier than employees with their salary, supervisor conduct, job position, autonomy at work, acknowledgment for good performance, job security, participation in decision making and open communication. According to Bjaalid et al. [84] and Hassan et al. [81], those who feel they have better relationships with their coworkers and immediate superiors report upper levels of job satisfaction. The findings illustrate the z-value strongly showed that there was not any substantial difference in foremen and workers’ satisfaction. However, foremen reported somewhat better levels of job satisfaction than laborers. The findings revealed that worker level had minimal influence on job satisfaction, and the foreman’s average job satisfaction score did not differ considerably from that of the workers. Furthermore, Table 6, which focuses on the negligible satisfaction score between foremen and workers in various departments, demonstrates that the F-ratio for each employee level (foreman and worker) and two-way interactions were not statistically significant.

According to the findings of this study, job satisfaction has a direct and significant influence on job performance. As a result, personal characteristics have a considerable influence on job performance. Job facets influence job performance by mediating job satisfaction. Job satisfaction has a direct impact on job performance by mediating the demographic and job characteristics. Work satisfaction studies show a favorable association between job satisfaction and job performance [76,78]. The current study’s findings also indicated that satisfied workers perform better than unsatisfied workers in terms of quality of work, quantity of work, job knowledge, initiative, creativity, cooperativeness, undependability, and personal development. Similarly, Rachman [80] discovered a favorable link between work quality and job satisfaction. The results showed a significant positive relationship between job performance and demographic traits as well as a significant positive relationship between job satisfaction and job performance (Table 14 and Table 15). Further, the results of the present study found a substantial positive association between almost all job-related characteristics and job performance (Table 14). This study supported the findings of Okechukwu [74]. In the investigation, they discovered that pleasure and performance had relationship [20]. This study argues from Abdulkhaliq and Mohammadali [37], who claim employment satisfaction.

According to the current study, all job-related factors, such as quality of work, quantity of work, job knowledge, initiative, creativity, cooperation, reliability, and personal development, have a significant impact on performance results (Table 14). Furthermore, the study’s findings revealed that satisfied employees were self-motivated, highly creative, cooperative, and performed tasks in a variety of ways with initiative. Therefore, the results of this investigation support and accept the null hypothesis (H4). Research findings from Eliyana and Sridadi [75] supported the beneficial association between employee quality of work, amount of work, and job happiness. Furthermore, satisfied employees are more likely to develop innovative approaches, ideas, and initiatives to meet company goals. The findings of Nduati and Wanyoike [36] indicated that when job satisfaction declines, so does performance. According to the research by Satorre [68], job happiness has a direct impact on job performance, through job aspects. It has also been demonstrated that personal characteristics and aspects of the work can moderate the impact of job satisfaction on output. According to research by Chan [63], job satisfaction has a considerable impact on employees’ job performance (Table 16), which amplifies the impact of workplace spirituality on employees’ job performance. This conclusion is consistent with that research. The results of this investigation concur with those of Arijanto’s [69] study.

In a suitable way, the study’s findings supported the hypothesis. Employee job satisfaction has been examined in Bangladesh’s sugar industry. The results of the current study revealed how sugar industry employees’ job happiness affected their performance at work. This study has significant ramifications. Most individuals believe that job performance is influenced by job satisfaction [12]. It is recognized that this association may not be causative based on the findings of this study. When job happiness is accompanied with organizational collegial support, performance might be impacted.

6. Conclusions

Each and every firm needs a contented workforce; job satisfaction plays in enhancing employees’ performance. The purpose of the current study is to understand employee job satisfaction and its association and effects on job performance. One of Bangladesh’s principal state-owned sectors is the sugar industry sector; there is no denying this industry’s importance to Bangladesh’s economy. This sector has not only met the local market’s need for premium sugar, but it has also given many people job possibilities. Attempts have been made to modernize the sugar business, along with other industrial sectors in Bangladesh, and as part of such initiatives, workers’ job satisfaction is being given considerable thought. The employees in this business have a significant role in whether Bangladesh’s sugar industry succeeds or fails. Job satisfaction varies across employees since it is a personal experience for each person. Every employee has a variable amount of skill to perform a task, thus each one will have varying levels of pleasure. Performance is based on the sum of all acquired ability, effort, and opportunities. The work satisfaction statement’s average yield value displays a high average overall. According to this study, overall job satisfaction level of the employees of Bangladesh’s sugar industry are satisfactory and the foreman’s mean job satisfaction score was much greater than the worker’s. Between high and low age groups, the average level of work satisfaction greatly varied. Employees, who are older, experienced and married report being happier at work than responders who are younger. The sugar industry authorities should thus design different initiatives for the current low-age workforce to maximize satisfaction. The groups of respondents with more experience and less education were shown to be happier. In order to maintain and recruit experienced and highly educated responders, sugar mill authorities may take additional care. The results of the present study show that job satisfaction directly effects job performance. Job satisfaction materials have a positive relationship, especially with personal factors and job factors, that is, they affect job performance, and especially job factors are established as more influencing factors. It was demonstrated that there is a relationship between job happiness and employee performance in the sugar industry in Bangladesh, with significant regression findings showing job satisfaction contributes toward employee performance. This result recommends that Bangladesh sugar industry authorities should focus on elements particularly job factors that can raise employee performance.

The findings of this study can be used not only for the sugar industry but also for other industries in Bangladesh. Many industries in Bangladesh are characterized by a large number of workers, as with the sugar industry. The recommendations of this study can be used in policy making to boost up employee job satisfaction and performance and initiatives can be taken to remove barriers, i.e., in the jute industry, textile industry, cement industry and chemic industry.

This research study stands out because of a few of its strengths. Such a study with employees of the sugar industry in Bangladesh is, to put it mildly, extremely uncommon. The study that was completed by the researchers in the indicated subject will be remembered as a turning point in Bangladesh. The amount of study on job satisfaction and its impact on job performance is abundant. Numerous studies have been conducted, are being conducted, and will continue to be conducted, but sugar industrial workers’ job satisfaction and job performance related research is still too short. Our study is more unique and fundamental since there is less field-related literature for the sugar sector. The methodology of this study is another excellent element. The widely accepted measuring scale has been used for data analysis. Direct interviews were used to gather the data, ensuring that the evidence was reliable and that the validity and reliability values were at the expected levels. One of the main characteristics of this research is the scientifically rigorous way in which it was carried out from beginning to end, with a supervisor giving it a close look. This research contains limitations just as other research does. The sampling technique used is the first factor. Nevertheless, we used five separate sugar mills to gather the sample. Public owned sugar mills were included in the study’s overall population, although not all of them were included in the sample. As a result, the researcher might not be able to extrapolate the findings to all the sugar mills in the nation. As a result, just 300 of Bangladesh’s thousands of sugar mill workers were included in the study, which focuses on how job satisfaction affects the work performance of sugar industrial employees of only (5) five nationalized sugar mills. The research population’s geographic scope is yet another drawback. Researchers had to select modest sample sizes as a result of a lack of funds and time, which hampered the conduct of high-quality research. With the use of contemporary research techniques, by taking into account the constraints of the present study, the huge sample size, and sugar mills in general, it is hoped that the future scholars should be able to create an accurate representation of employees’ job satisfaction. The probable existence of some common approach bias is still another constraint. In our study, we analyzed the data for evaluating work performance and job satisfaction using two frequently used, but rather old, approaches. As a statistical tool, we utilized SPSS software to obtain data that were likewise rather old. The results should be evaluated cautiously since the self-evaluation of performance may introduce this bias. This result is in line with findings from earlier research on common method variance, which come to the conclusion that, even when communal method bias is present, it often does not have a major impact on the data’s results or inferences.

Future research can use the updated methodology to construct a new research framework using a larger sample size. In that case other demographic factors and job related factors can be considered. Sugar mills under the sugar industry of Bangladesh need to be included in the research, and then a proper understanding of the job satisfaction and job performance of the workers in different regions of the country can be obtained. Future research could use more content-rich questionnaires and measurement scales to obtain accurate results. Future studies should look at the link between job performance and job happiness in terms of causality. Third, because the current study only examined personal characteristics and job facets in terms of job satisfaction and its effects on job performance, future studies should increase the number of outcome variables taken into account and, thus, confirm our findings. Fourth, given the findings of the current study, it is crucial to investigate various research based on various factors affecting job satisfaction and behavior.

This study adds to the body of knowledge about job satisfaction by emphasizing job performance, which is connected to the congruence between workers’ personal characteristics and workplace aspects. The degree of significance may be seen as a dynamic resource that can change depending on the demands of the job, the performance standards, and other personal characteristics of the employee. The government, policymakers, and personnel department of Bangladesh’s sugar mills will find the results and conclusions useful in developing strategies for enhanced performance and work satisfaction. In order to make organizational decisions and establish rules pertaining to work performance, it is possible to assess job satisfaction and the impact of job performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.I.G.; data curation, M.A.I. and B.K.D.; funding acquisition, J.S.; methodology, M.A.I.G.; project administration, M.A.I.; resources, J.S.; supervision, M.A.I.; visualization, M.A.I.G. and B.K.D.; writing—original draft, M.A.I.G.; writing—review and editing, M.A.I.G., M.A.I. and J.S.; software, B.K.D.; validation, J.S.; writing—review and editing, M.A.I., B.K.D. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gazi, M.A.I.; Islam, M.A.; Sobhani, F.A.; Dhar, B.K. Does Job Satisfaction Differ at Different Levels of Employees? Measurement of Job Satisfaction Among the Levels of Sugar Industrial Employees. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, P.D.G.K.; Suwandana, I.G.M. The Role of Job Satisfaction, Work-life Balance on the Job Performance of Female Nurses at Local General Hospital. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2022, 7, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Thang, D.; Nghi, N.Q. The effect of work motivation on employee performance: The case at OTUKSA Japan Company. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2022, 13, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inayat, W.; Khan, M.J. A Study of Job Satisfaction and Its Effect on the Performance of Employees Working in Private Sector Organizations, Peshawar. Educ. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 1751495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Shmailan, A.S. The relationship between job satisfaction, job performance and employee engagement: An explorative study. Bus. Manag. Econ. 2016, 4, 27948529. [Google Scholar]

- Peiró, J.M.; Bayona, J.A.; Caballer, A.; Di Fabio, A. Importance of work characteristics affects job performance: The mediating role of individual dispositions on the work design-performance relationships. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 2020, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayona, J.A.; Caballer, A.; Peiró, J.M. The Relationship between Knowledge Characteristics’ Fit and Job Satisfaction and Job Performance: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrianto, Y.; Ekhsan, M. Effect of work environment and job satisfaction on employee performance in Pt. Nesinak Industries. J. Bus. Manag. Account. 2020, 2, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Dunnette, M.D. The Handbook of Industrial and Organisational Psychology; John Wiley & Son Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.A.; Abbasi, S.O.B.H.; Waseem, R.M.; Ayaz, M.; Ijaz, M. Impact of training and development of employees on employee performance through job satisfaction: A study of telecom sector of Pakistan. Bus. Manag. Strateg. 2016, 7, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariani, M.; Ratnasari, D. Effect of emotional intelligence against employee performance in department of labor and social. J. Bus. Financ. Emerg. Mark. 2018, 1, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.S.; Rafie, N.; Selo, S.A. Job Satisfaction Influence Job Performance among Polytechnic Employees. Int. J. Mod. Trends Soc. Sci. 2020, 3, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jufrizen, J.; Farisi, S.; Azhar, M.E.; Daulay, R. The Effect of Job Satisfaction, Work Motivation and Organizational Commitment on Performance Through Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) as an Intervening Variable. Econ. Educ. Anal. J. 2017, 6, 365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Takaya, R.; Ramli, A.H.; Lukito, N. The effect of advertisement value and context awareness value on purchase intention through attitude brands and advertising attitude in smartphone advertising. Int. J. Creat. Res. Stud. 2019, 3, 106–118. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiq, A.; Takreem, K.; Iqbal, K. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment: A case study of hospitals in Pakistan. Peshawar J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2017, 2, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazmahadi, Y.Z.; Basri, K.; AH, R. The Influence of Strategic Management Information System, Strategic Partnership on Organizational Performance Mediated by Organizational Culture in Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Service Center in Indonesia. Int. J. Creat. Res. Stud. 2020, 4, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mariam, S.; Ramli, A.H. Peran Mediasi Strategic Change Management pada Usaha Mikro Kecil dan Menengah dalam Kondisi Pandemik Covid-19. In Prosiding Seminar STIAMI; STIAMI Institute: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020; Volume 7, pp. 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, C. The Impact of Training and Development, Job Satisfaction and Job Performance on Young Employee Retention. Int. J. Future Gener. Commun. Netw. 2020, 13, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Lodhi, S.A.; Raza, B.; Ali, W. Examining the impact of managerial coaching on employee job performance: Mediating role of work engagement, leader-member-exchange quality, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2018, 12, 253–282. [Google Scholar]

- Torlak, N.G.; Kuzey, C. Leadership, job satisfaction and performance links in private education institutes of Pakistan. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2019, 68, 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kaiser, M.; Nie, P.; Sousa-Poza, A. Why are Chinese workers so unhappy? A comparative cross-national analysis of job satisfaction, job expectations, and job attributes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, A.H. Employee Innovation Behavior in Health Care. In International Conference on Management, Accounting, and Economy; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tingo, A.; Mseti, S. Effect of Employee Independence on Employee Performance. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2022, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, J.M.; Drasgow, F. The Psychology of Work: Theoretically Based Empirical Research; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, W. Understanding the concept of Job Satisfaction, Measurements, Theories and its significance in the Recent Organizational Environment: A Theoretical Framework. Arch. Bus. Res. 2016, 4, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsakis, M.; Galanakis, M. An Empirical Examination of Herzberg’s Theory in the 21st Century Workplace. Organizational Psychology Re-Examined. Psychology 2022, 13, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongo, J.S.; Tesha, D.N.G.A.K.; Kasonga, R.; Luvara, V.G.M.; Mwanganda, R.J. Job Satisfactions of Quantity Surveyors in Building Construction Firms in Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania. Int. J. Eng. Manag. Res. 2019, 9, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.; LePine, J.; Wesson, M. Organizational Behavior: Improving Performance and Commitment in the Workplace; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Gazi, M.A.I.; Rahaman, M.A.; Hossain, G.M.A.; Ali, M.J.; Mamoon, Z.R. An empirical study of determinants of customer satisfaction of banking sector: Evidence from Bangladesh. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 497–503. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.; Lake, C.J. Contingent worker monetary influence, work attitudes and behavior. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 1669–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haidan, S.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Elshaer, I.A. Social Disconnectedness and Career Advancement Impact on Performance: The Role of Employees’ Satisfaction in the Energy Sector. Energies 2022, 15, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayah, T.; Tobing, D.S.K. The Influence of Job Satisfaction. Motivation, And Organizational Commitment to Employee Performance. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2018, 7, 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, M.A.; Alshagawi, M.; Zakariya, A.; Juhari, A.S. Do multicultural faculty members perform well in higher educational institutions?: Examining the roles of psychological diversity climate, HRM practices and personality traits (Big Five). Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2019, 43, 166–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A. The mediating role of job satisfaction in the relationship of vertical trust and distributed leadership in health care context. J. Model. Manag. 2016, 11, 722–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwatayo, A.A.; Adetoro, O. Influence of Employee Attributes, Work Context and Human Resource Management Practices on Employee Job Engagement. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2020, 21, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nduati, M.M.; Wanyoike, R. Employee performance management practices and organizational effectiveness. Int. Acad. J. Hum. Resour. Bus. Adm. 2022, 3, 361–378. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulkhaliq, S.S.; Mohammadali, Z.M. The Impact of Job Satisfaction on Employees Performance: A Case Study of Al Hayat Company—Pepsi Employees in Erbil, Kurdistan Region—Iraq. Manag. Econ. Rev. 2019, 4, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.S. Strategic Human Resource Management Practices and Competitive Priorities of the Manufacturing Performance in Karachi. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2015, 16, 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siahaan, R. Effect of Work Environment on Employee Satisfaction with Work Communication as Intervening Variables. J. Educ. Lang. Res. 2022, 1, 987–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, S.P.; Judge, T.A. Organizational Behavior, 18th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, N.W.; Briley, D.A.; Chopik, W.J.; Derringer, J. You have to follow through: Attaining behavioral change goals predicts volitional personality change. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 117, 839–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.T.; Tran, M.U. Factors Affecting Satisfaction of Customers’ Savings Deposit in the Context of COVID-19: Evidence from Vietnamese Commercial Banks. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesurado, B.; Crespo, R.; Rodriguez, O.; Debeljuh, P.; Idrovo, S. The development and initial validation of the multidimensional flourishing scale. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 40, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariam, S. Job Satisfaction Employees Hospital. Bus. Entrep. Rev. 2019, 19, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Diana, E.A.; Emur, A.P.; Sridadi, A.R. Building nurses’ organizational commitment by providing good quality of work life. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 142–150. [Google Scholar]

- Santhoshkumar, G.; Jayanthy, S.; Velanganni, R. Employees Job Satisfaction. J. Adv. Res. Dyn. Control Syst. 2019, 11, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, T. Job Satisfaction and Implications for Organizational Sustainability: A Resource Efficiency Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Gazi, M.A.I. Job Satisfaction in Relation to Personnel Policies and Practices in Sugar Industry of Bangladesh: A Study on Rajshahi Sugar Mills Ltd. J. Bus. Stud. (PUST) 2020, 4, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh, T.M.; Kraiger, K.; Henry, K. Age-related changes on the effects of job characteristics on job satisfaction: A longitudinal analysis. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2020, 91, 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, F.M.; Akter, T. Impact of Demographic Factors on the Job Satisfaction: A Study of Private University Teachers in Bangladesh. SAMSMRITI SAMS J. 2019, 12, 62–80. [Google Scholar]

- Abuhashesh, M.; Al-Dmour, R.; Masa’deh, R. Factors that affect Employees Job Satisfaction and Performance to Increase Customers’ Satisfactions. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Res. 2019, 2019, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiou, S.; Garametsi, V. Perceived leadership style and job satisfaction of teachers in public and private schools. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 15, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Kim, S.; Jung, J. The effects of a Master’s Degree on wage and job satisfaction in massified higher education: The case of South Korea. High. Educ. Policy 2020, 33, 637–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-W.; Cho, Y.-H. The moderating effect of managerial roles on job stress and satisfaction by employees’ employment type. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Akey-Torku, B. The Influence of Managerial Psychology on Job Satisfaction among Healthcare Employees in Ghana. Healthcare 2020, 8, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Deery, S. Why do self-initiated expatriates quit their jobs: The role of job embeddedness and shocks in explaining turnover intentions. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.S.M. Job Satisfaction of Bank Employees in Bangladesh: A Comparative Study Between Private and State-Owned Banks. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 21, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kampf, P.H.; Hernández, A.; González-Romá, V. Antecedents and consequences of workplace mood variability over time: A weekly study over a three-month period. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2020, 94, 160–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, M.A.; Gonzalez, J.A.; Wang, Y. Job flexibility and job satisfaction among Mexican professionals: A socio-cultural explanation. Empl. Relat. 2018, 40, 921–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, N.; Fernández Puente, A.C. Public versus private job satisfaction. Is there a trade-off between wages and stability? Public Organ. Rev. 2021, 21, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M. Understanding the Nuances of Employees’ Safety to Improve Job Satisfaction of Employees in Manufacturing Sector. J. Health Manag. 2019, 21, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, M.J.; Popovici, I.; Hardigan, P.C. Gender and age variations in pharmacists’ job satisfaction in the United States. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.C.H. Participative leadership and job satisfaction. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachman, M.M.; Sugijanto, A.; Samsiyah, S. The effect of transformational leadership on the performance of employees with motivation and job satisfaction as an intervention (A Study on the Office of the Department of Irrigation works in the District of Sidoarjo, Indonesia). Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nuangjamnong, C. The COVID-19 Epidemic with Employees’ Job Satisfaction and Performance on Work from Home during Lockdown in Bangkok. Psychol. Educ. J. 2022, 59, 416–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saragih, J.; Tarigan, A.; Pratama, I.; Wardati, J.; Silalahi, E.F. The Impact of Total Quality Management, Supply Chain Management Practices and Operations Capability on Firm Performance. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 21, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Loh, H.S.; Zhou, Q.; Wong, Y.D. Determinants of job satisfaction and performance of seafarers. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 110, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satorre, C.L. The effect of organizational climate on the teachers’ performance and job satisfaction in selected secondary schools in the Division of Albay. Puissant 2022, 3, 381–394. [Google Scholar]

- Arijanto, A. How to The Impact on Transformational Leadership Style and Job Motivation on Organizational Citizenship Behaviour (OCB) With Job Satisfaction as Mediating Variables at Outsourcing Company Cognizance. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2022, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, N.; Wald, A. Similar but different? The influence of job satisfaction, organizational commitment and person-job fit on individual performance in the continuum between permanent and temporary organizations. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2022, 40, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Beaskoetxea, J.; García, C. Media image of seafarers in the Spanish printed press. Marit. Policy Manag. 2015, 42, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P. Influence of University teachers’ job satisfaction on subjective well-being and job performance. J. Eng. Educ. Transform. 2022, 35, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolocha, C.B.; Akam, G.U.; Uchehara, F.O. Effect of job satisfaction on job performance of university lecturers in South-East, Nigeria. Int. J. Manag. Stud. Soc. Sci. Res. 2021, 3, 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Okechukwu, W. Influence of Training and Development, Employee Performance on Job Satisfaction among the Staff of School of Technology Management and Logistics, Universiti UtaraMalaysia. J. Technol. Manag. Bus. 2017, 4, 168736524. [Google Scholar]

- Oravee, A.; Zayum, S.; Kokona, B. Job Satisfaction and Employee Performance in NasarawaState Water Board, Lafia, Nigeria. Cimexus 2018, 13, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustina, D.; Berliyanti, D.; Ariyani, I. Job Performance dan Job Satisfaction Wartawan Sebagai Dampak Job Stress Di Masa Pandemi COVID-19. J. Bisnis Dan Manaj. 2022, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyaningrum, H.M.E.; Rachman, M.M. The Influence of the Work Environment, Organizational Commitment and Organizational Citizenship Behavior on Employee Performance and Motivation as Intervening. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 11, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.H.; Chen, H.T. Relationships among workplace incivility, work engagement and job performance. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2020, 3, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohmawati, H.; Maya, S.; Robbani, H. The Effect of Job Stress and Job Satisfaction on Employee Performance PT Famed Calibration. FOCUS 2020, 1, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachman, M. The Impact of Work Stress and the Work Environment in the Organization: How Job Satisfaction Affects Employee Performance? J. Hum. Resour. Sustain. Stud. 2021, 9, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Azmat, U.; Sarwar, S.; Adil, I.H.; Gillani, S.H.M. Impact of job satisfaction, job stress and motivation on job performance: A case from private universities of Karachi. Kuwait Chapter Arab. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2020, 9, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gün, İ.; Söyük, S.; Özsari, S.H. Effects of Job Satisfaction, Affective Commitment, and Organizational Support on Job Performance and Turnover Intention in Healthcare Workers. Arch. Health Sci. Res. 2021, 8, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, A.L.; Rivai, H.A.; Yulihasri, Y. Impact of Job Stress on Job Performance of Health Worker with Work Life Balance as Mediating Variable. Manag. Anal. J. 2022, 11, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bjaalid, G.; Olsen, E.; Melberg, K.; Mikkelsen, A. Institutional Stress and Job Performance Among Hospital Employees. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2019, 28, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A.; Rehman, F.U.; Imran, M.; Ali, M.; Almansoori, R.G. Authentic Leadership Traits, High Performance Human Resource Practices and Job Performance in Pakistan. Int. J. Public Leadersh. 2020, 16, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrazehi, H.A.A.W.; Amirah, N.A.; Emam, A.S.; Hashmi, A.R. Proposed model for entrepreneurship, organizational culture, and job satisfaction towards organizational performance in International Bank of Yemen. Int. J. Manag. Hum. Sci. 2021, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Rasheed, R.; Rashid, A.; Abbas, O.; Mahboob, F. The Effect of Demographic Characteristics on Job Performance: An Empirical Study from Pakistan. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2022, 9, 283–294. [Google Scholar]