Artificial Intelligence’s Role in Predicting Corporate Financial Performance: Evidence from the MENA Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. AI and Corporate Financial Performance Prediction

2.2. Random Forests (RFs) and Corporate Financial Performance Prediction

2.3. XGBoost and Corporate Financial Performance Prediction

2.4. SVMs and Corporate Financial Performance Prediction

2.5. DNNs and Corporate Financial Performance Prediction

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Selection

3.2. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

4.2. Model Performance Evaluation

4.2.1. Random Forests

4.2.2. XGBoost

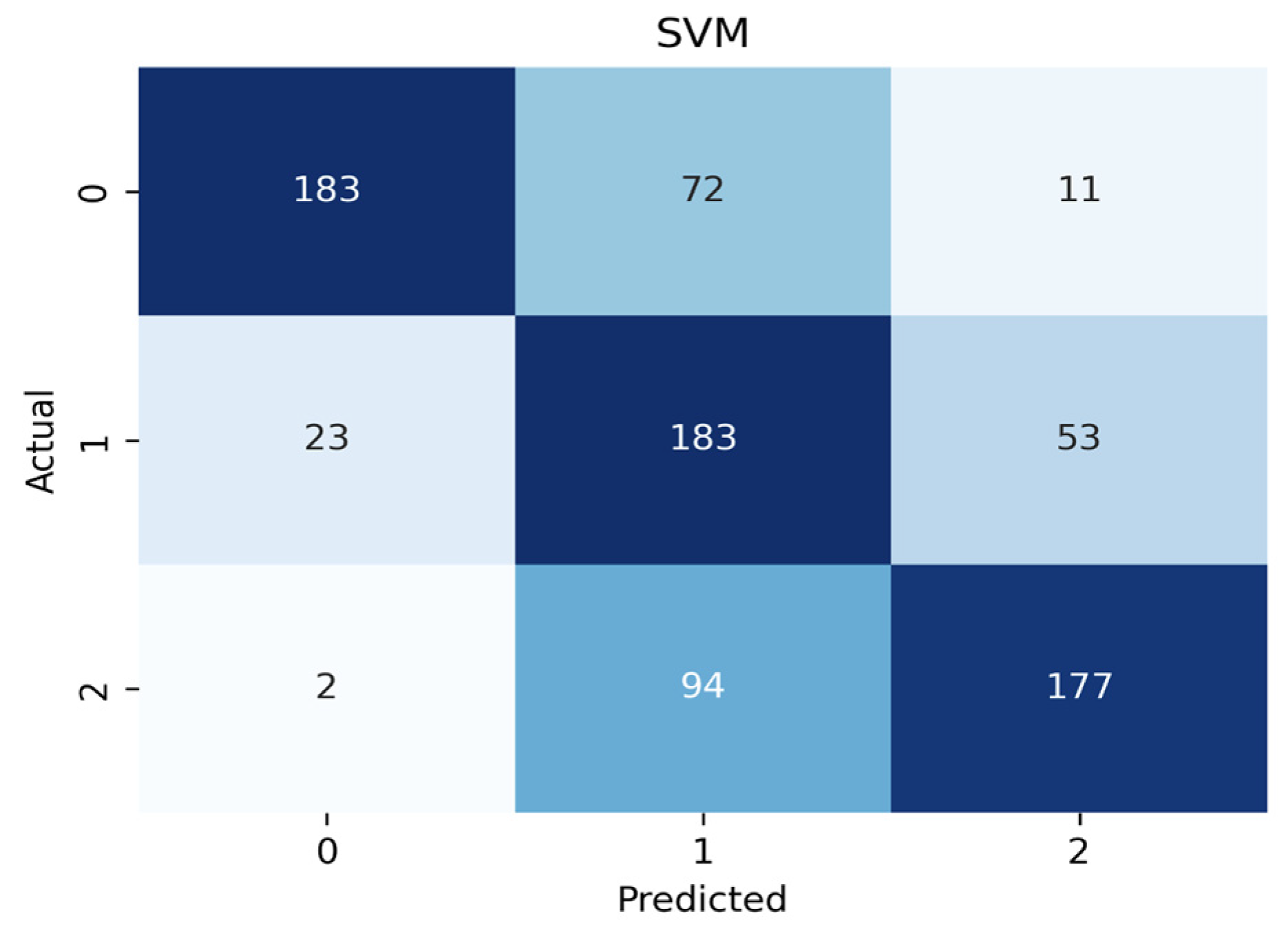

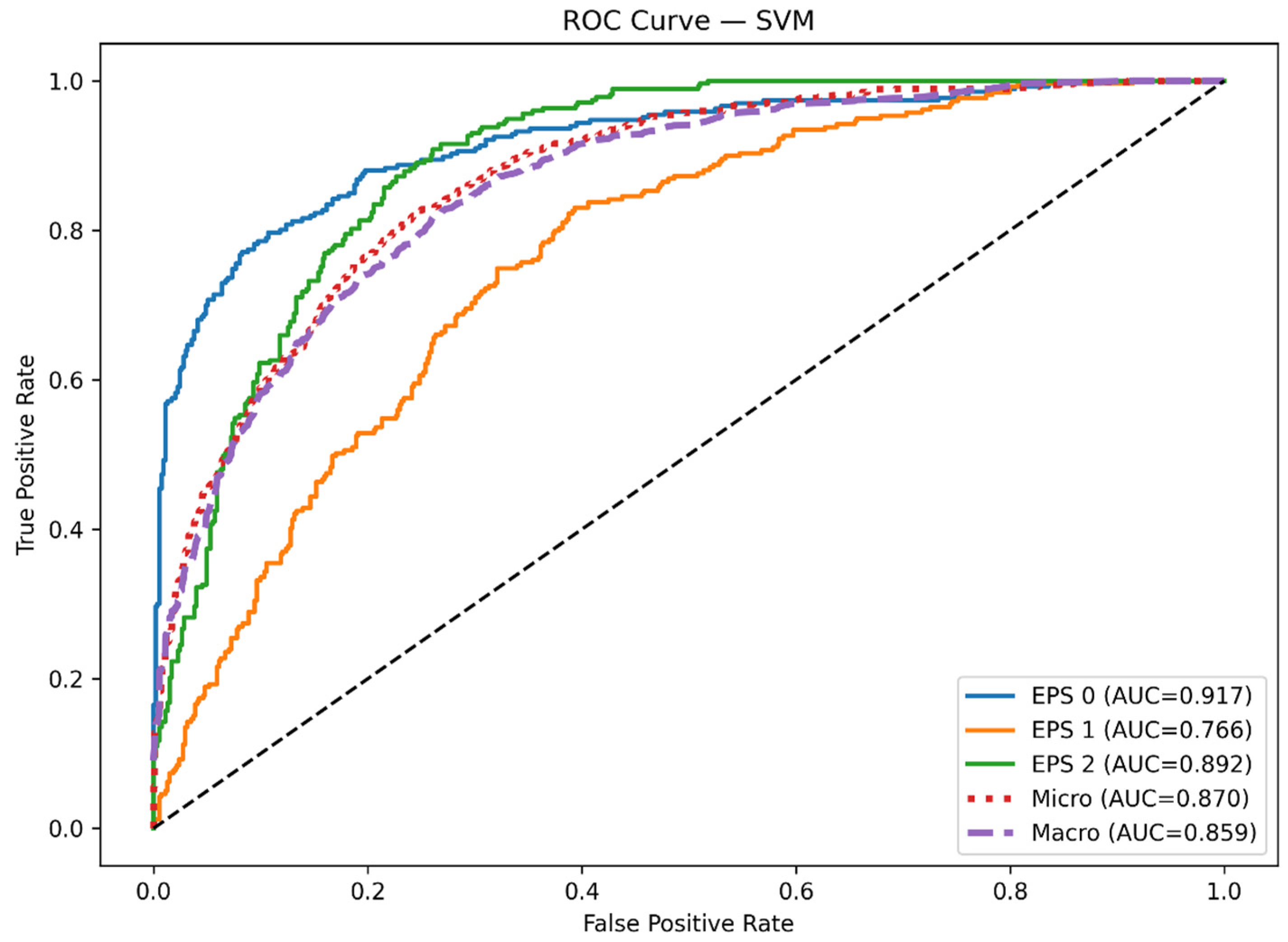

4.2.3. SVMs

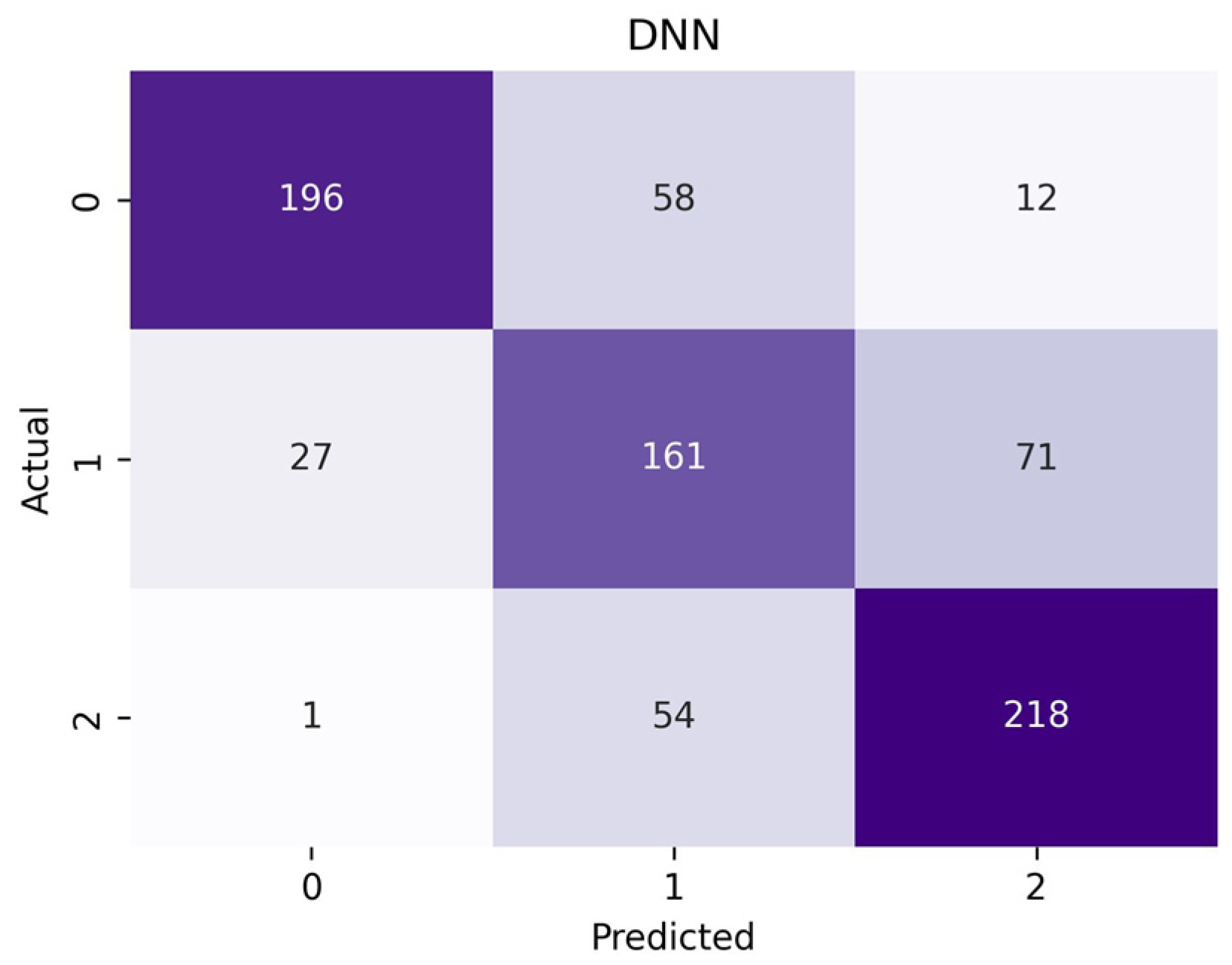

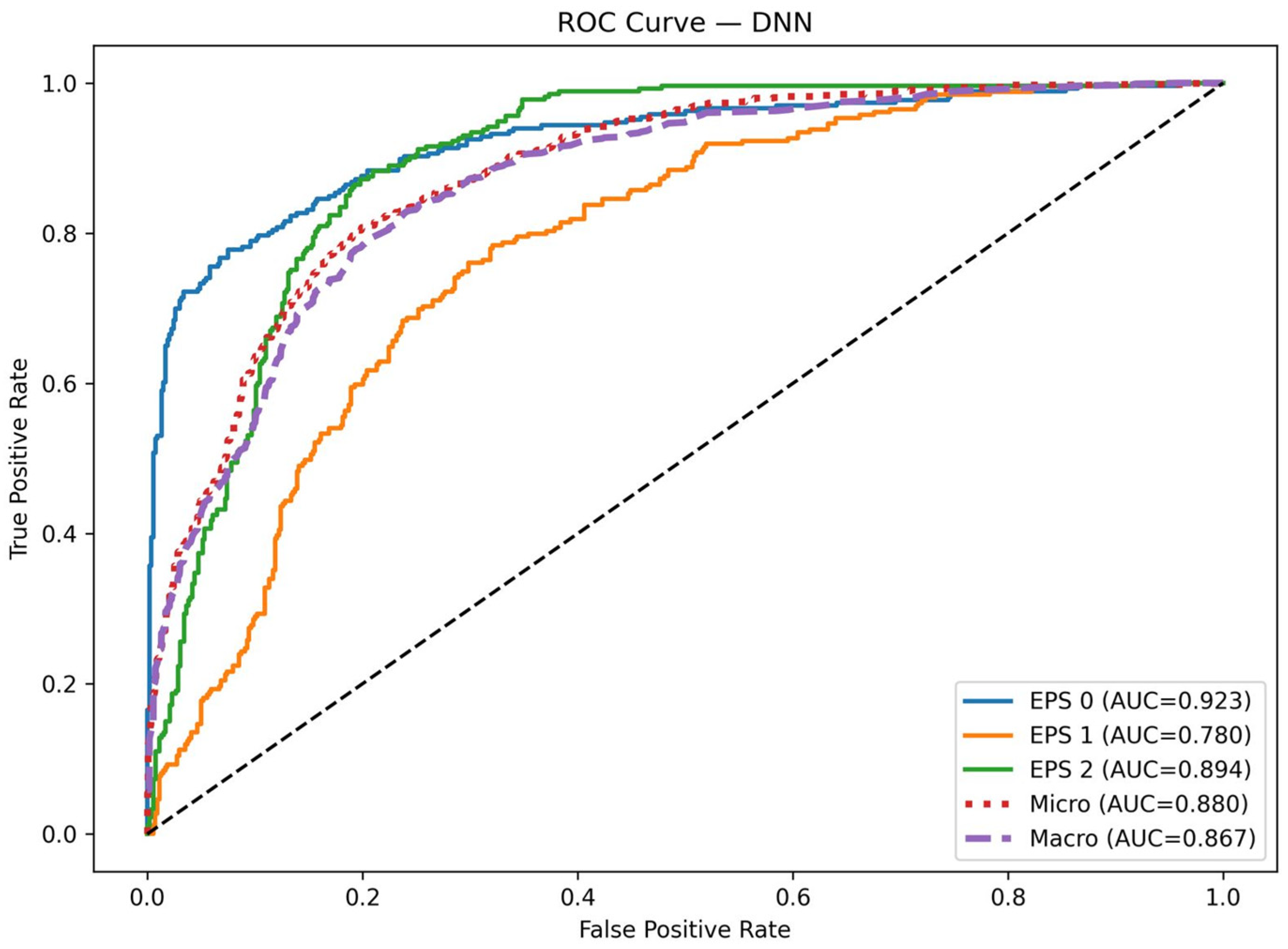

4.2.4. Deep Learning

4.3. Performance Evaluation Using ROC-AUC, Macro- and Micro-Averaged ROC-AUC, and Average Precision

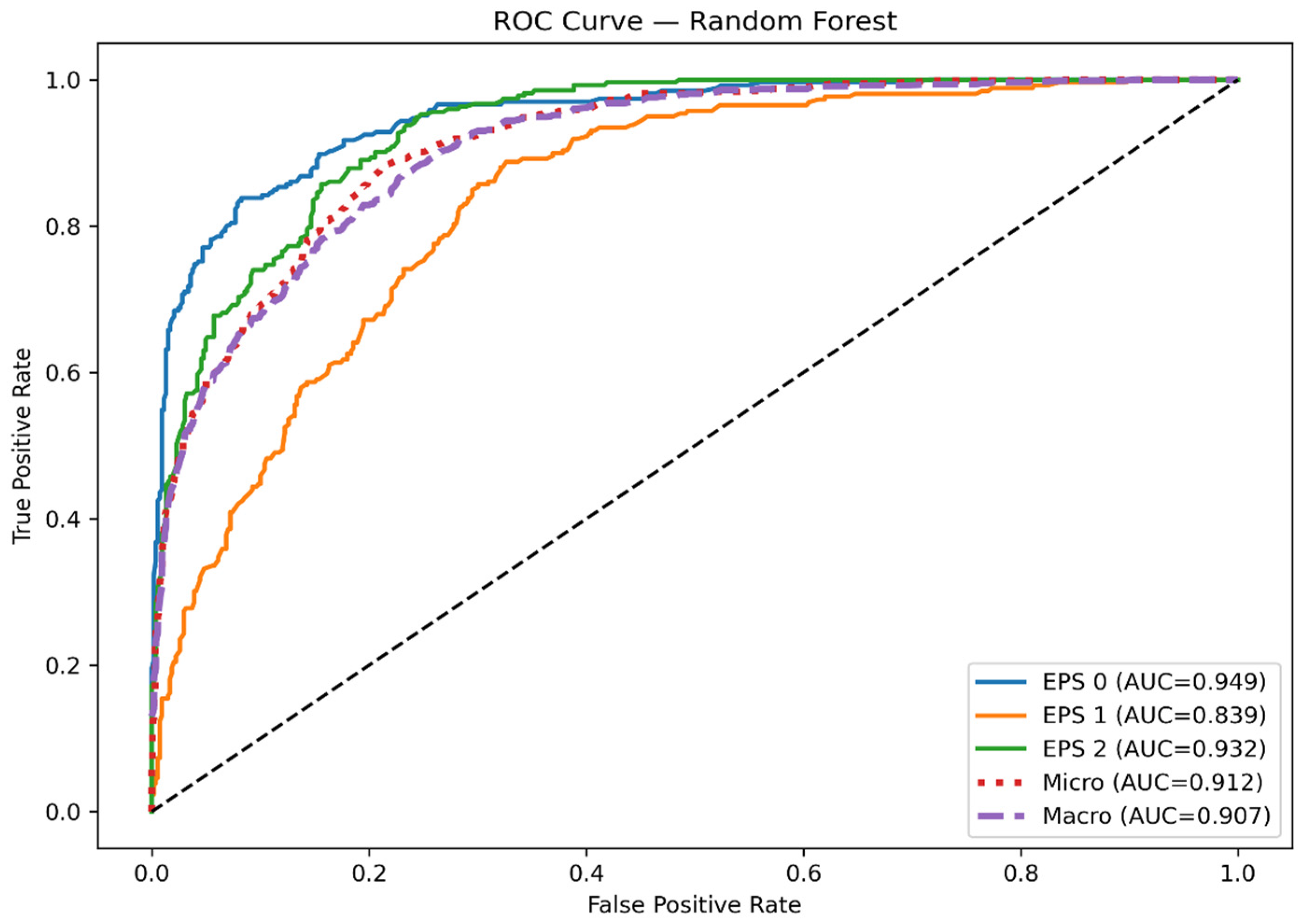

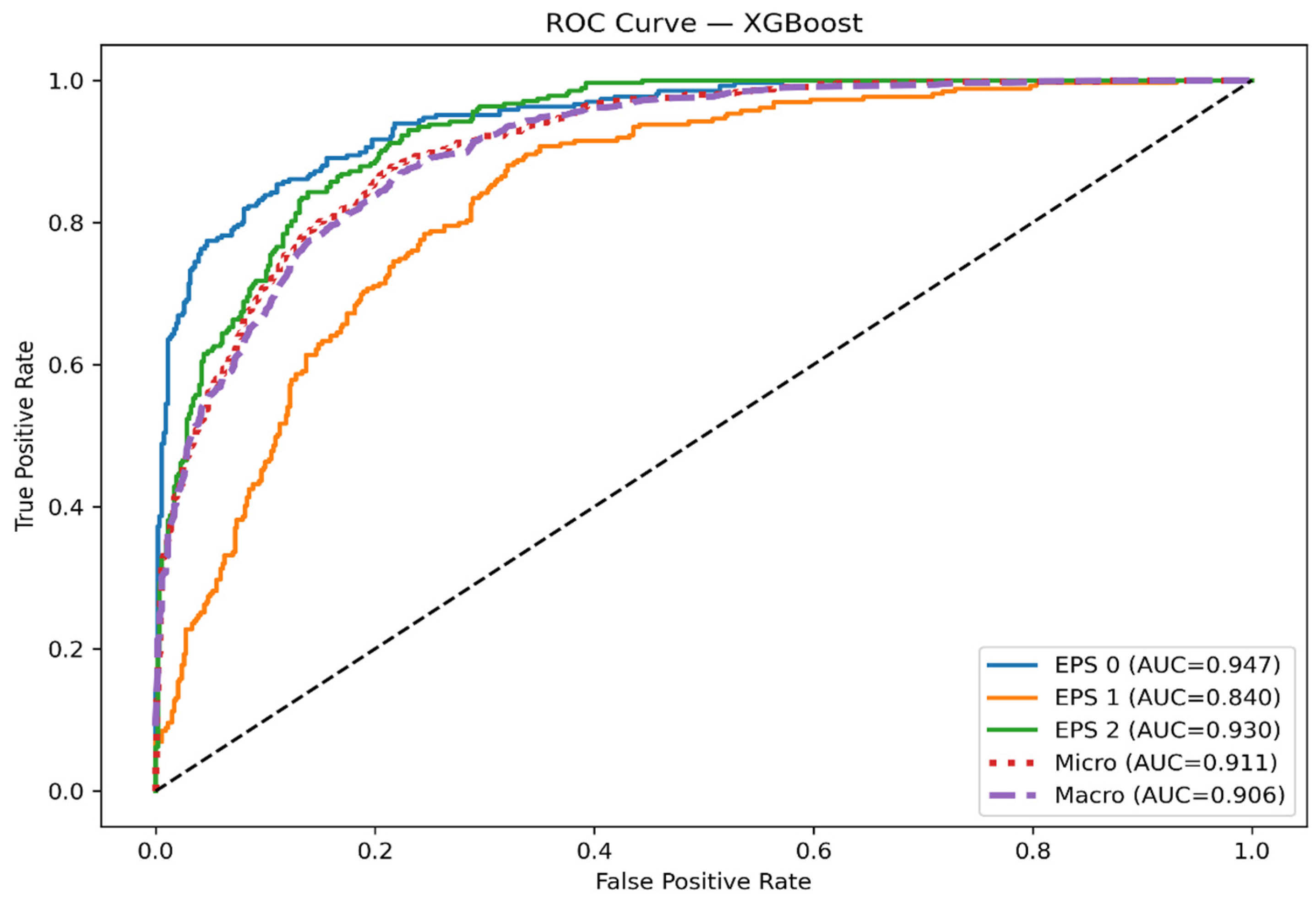

4.3.1. ROC Curve Results

4.3.2. Macro- and Micro-Averaged ROC-AUC and Average Precision Results

4.3.3. Feature Importance

4.4. Robustness Check

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Research Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ML | Machine learning |

| DL | Deep learning |

| MENA | Middle East and North Africa |

| UAE | United Arab Emirates |

| DSR | Design science research |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| RF | Random forest |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| DNNs | Deep neural networks |

| EPS | Earnings per share |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| MDA | Multivariate discriminant analysis |

| ANN | Artificial neural networks |

| Logit | Logistic regression |

| SVM-Lin | Linear SVM |

| SVM-RBF | Radial basis function SVM |

| GBM | Gradient boosting machine |

| CatBoost | Categorical boosting |

| HACT | Hybrid associative memory with translation |

| DBN | Deep belief network |

| LDA | Linear discriminant analysis |

| RL | Reinforcement learning |

| EBIT | Earnings before interest and taxes |

| TP | True positive |

| TN | True negative |

| FP | False positive |

| FN | False negative |

| PNNs | Probabilistic neural networks |

Appendix A

| Model | Accuracy (Median) | Accuracy (KNN) | Cohen’s Kappa (Median) | Cohen’s Kappa (KNN) | ROC AUC (Macro) (Median) | ROC AUC (Macro) (KNN) | Correctly Classified (Median) | Correctly Classified (KNN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVMs | 0.680451 | 0.671679 | 0.521528 | 0.508596 | 0.858428 | 0.852 | 543 | 536 |

| RFs | 0.735589 | 0.733083 | 0.603389 | 0.59965 | 0.906639 | 0.898 | 587 | 585 |

| XGBoost | 0.754386 | 0.744361 | 0.631639 | 0.616617 | 0.9056 | 0.9 | 602 | 594 |

| DNNs | 0.720551 | 0.709273 | 0.580633 | 0.564025 | 0.865629 | 0.86 | 575 | 566 |

References

- Abdellatif, E. M., Saleh, S. A. F., & Hamed, H. N. (2023). Corporate financial performance prediction using artificial intelligence techniques. In World conference on internet of things: Applications & future (pp. 25–32). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. F., Alam, M. S. B., Hassan, M., Rozbu, M. R., Ishtiak, T., Rafa, N., Mofijur, M., Shawkat Ali, A. B. M., & Gandomi, A. H. (2023). Deep learning modelling techniques: Current progress, applications, advantages, and challenges. In Artificial intelligence review (Vol. 56, Issue 11). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T., Zehra, F., Tariq, S., Qureshi, S., Manzoor, G., Hussaini, W., Mustafa, M. L., Khalil, A., & Zeeshan, M. (2025). Advanced financial system architecture using deep neural networks for accurate risk assessment and high-value transaction prediction in modern banking. Journal of Management Science Research Review, 4(3), 698–732. [Google Scholar]

- Alauddin, M., & Nghiemb, H. S. (2010). Do instructional attributes pose multicollinearity problem? An empirical exploration. Economic Analysis and Policy, 40(3), 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandropoulos, S. A. N., Kotsiantis, S. B., & Vrahatis, M. N. (2019). Data preprocessing in predictive data mining. Knowledge Engineering Review, 34, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. M., Rahman, A. U., Kabir, G., & Paul, S. K. (2024). Artificial intelligence approach to predict supply chain performance: Implications for sustainability. Sustainability, 16(6), 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljawazneh, H., Mora, A. M., Garcia-Sanchez, P., & Castillo-Valdivieso, P. A. (2021). Comparing the performance of deep learning methods to predict companies’ financial failure. IEEE Access, 9, 97010–97038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, J., Sony, M., Lameijer, B., Bhat, S., Jayaraman, R., & Gutierrez, L. (2024). Towards a design science research (DSR) methodology for operational excellence (OPEX) initiatives. TQM Journal, 36(8), 2383–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P., & Saurabh, S. (2022). Predicting distress: A post insolvency and bankruptcy code 2016 analysis. Journal of Economics and Finance, 46(3), 604–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, F., & Altman, E. (2024). Predicting financial distress in Latin American companies: A comparative analysis of logistic regression and random forest models. North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 72, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, F., Kimura, H., & Altman, E. (2017). Machine learning models and bankruptcy prediction. Expert Systems with Applications, 83, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Jabeur, S., Stef, N., & Carmona, P. (2023). Bankruptcy prediction using the XGBoost algorithm and variable importance feature engineering. Computational Economics, 61(2), 715–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, A. (2008). Comparison of classification accuracy using cohen’s weighted kappa. Expert Systems with Applications, 34(2), 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsimas, D., Pawlowski, C., & Zhuo, Y. D. (2018). From predictive methods to missing data imputation: An optimization approach. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 18, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Biju, A. K. V. N., Thomas, A. S., & Thasneem, J. (2024). Examining the research taxonomy of artificial intelligence, deep learning & machine learning in the financial sphere—A bibliometric analysis. Quality and Quantity, 58(1), 849–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billios, D., Seretidou, D., & Stavropoulos, A. (2024). The power of numerical indicators in predicting bankruptcy: A systematic review. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(10), 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A. F. S., Laurindo, F. J. B., Spínola, M. M., Gonçalves, R. F., & Mattos, C. A. (2021). The strategic use of artificial intelligence in the digital era: Systematic literature review and future research directions. International Journal of Information Management, 57, 102225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouke, M. A., & Abdullah, A. (2023). An empirical study of pattern leakage impact during data preprocessing on machine learning-based intrusion detection models reliability. Expert Systems with Applications, 230, 120715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, J. K. U., & von Wangenheim, F. (2019). Demystifying Ai: What digital transformation leaders can teach you about realistic artificial intelligence. California Management Review, 61(4), 110–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, P., Climent, F., & Momparler, A. (2019). Predicting failure in the U.S. banking sector: An extreme gradient boosting approach. International Review of Economics and Finance, 61, 304–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, V., Xu, Q. A., Chidozie, A., & Wang, H. (2024). Predicting economic trends and stock market prices with deep learning and advanced machine learning techniques. Electronics, 13(17), 3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L., Zhipeng, J., & Yuanjie, Z. (2019). A novel reconstructed training-set SVM with roulette cooperative coevolution for financial time series classification. Expert Systems with Applications, 123, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, D. J., & Chu, C. C. (2021). Artificial intelligence in corporate sustainability: Using lstm and gru for going concern prediction. Sustainability, 13(21), 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinonyerem, C. A., Olalemi, A. A., Paul, M., Nwabunike, O. T., Eniola, O. S., Benjamin, A. O., Ukeje, U., & Seigha, I. B. (2025). Leveraging machine learning and data analytics to predict corporate financial distress and bankruptcy in the United States. Asian Journal of Advanced Research and Reports, 19(6), 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordón, I., Luengo, J., García, S., Herrera, F., & Charte, F. (2019). Smartdata: Data preprocessing to achieve smart data in R. Neurocomputing, 360, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasilas, A., & Rigani, A. (2024). Machine learning techniques in bankruptcy prediction: A systematic literature review. Expert Systems with Applications, 255, 124761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delen, D., Kuzey, C., & Uyar, A. (2013). Measuring firm performance using financial ratios: A decision tree approach. Expert Systems with Applications, 40(10), 3970–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirdöğen, G., Işik, Z., & Arayici, Y. (2020). Lean management framework for healthcare facilities integrating BIM, BEPS and big data analytics. Sustainability, 12(17), 7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, M., Afolaranmi, S. O., Martinez Lastra, J. L., & Perez Garcia, J. A. (2023). A comprehensive literature review of the applications of AI techniques through the lifecycle of industrial equipment. In Discover artificial intelligence (Vol. 3, Issue 1). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhoseny, M., Metawa, N., Sztano, G., & El-hasnony, I. M. (2022). Deep learning-based model for financial distress prediction. Annals of Operations Research, 345(2), 885–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdosikova, D., & Michulek, J. (2025). Artificial intelligence models for bankruptcy prediction in agriculture: Comparing the performance of artificial neural networks and decision trees. Agriculture, 15(10), 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdosikova, D., Valaskova, K., & Lazaroiu, G. (2024). The relevance of sectoral clustering in corporate debt policy: The case study of slovak enterprises. Administrative Sciences, 14(2), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, R., Bose, I., & Chen, X. (2015). Prediction of financial distress: An empirical study of listed Chinese companies using data mining. European Journal of Operational Research, 241(1), 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholampoor, H., & Asadi, M. (2024). Risk analysis of bankruptcy in the U.S. healthcare industries based on financial ratios: A machine learning analysis. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 19(2), 1303–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregova, E., Valaskova, K., Adamko, P., Tumpach, M., & Jaros, J. (2020). Predicting financial distress of slovak enterprises: Comparison of selected traditional and learning algorithms methods. Sustainability, 12(10), 3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, M., Mestiri, S., & Arbi, A. (2024). Artificial intelligence techniques for bankruptcy prediction of tunisian companies: An application of machine learning and deep learning-based models. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(4), 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, A., Aït-Kaddour, A., Abu-Mahfouz, A. M., Rathod, N. B., Bader, F., Barba, F. J., Biancolillo, A., Cropotova, J., Galanakis, C. M., Jambrak, A. R., Lorenzo, J. M., Måge, I., Ozogul, F., & Regenstein, J. (2023). The fourth industrial revolution in the food industry—Part I: Industry 4.0 technologies. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 63(23), 6547–6563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, M. A., Ismail, M. A.-A., & Moubarak, H. (2025). Pioneer Jones vs the modifiers: Case of detecting accrual-based earnings management using advanced machine learning classifiers in an emerging economy. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/jfra/article-abstract/doi/10.1108/JFRA-12-2024-0902/1275983/Pioneer-Jones-vs-the-modifiers-case-of-detecting?redirectedFrom=fulltext (accessed on 10 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hevner, A. R. (2007). A three cycle view of design science research. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 19(2), 4. [Google Scholar]

- Hezam, Y., Luong, H., & Anthonysamy, L. (2025). Machine learning in predicting firm performance: A systematic review. China Accounting and Finance Review, 27(3), 309–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosaka, T. (2019). Bankruptcy prediction using imaged financial ratios and convolutional neural networks. Expert Systems with Applications, 117, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W., Shao, C., & Zhang, W. (2025). Predicting U.S. bank failures and stress testing with machine learning algorithms. Finance Research Letters, 75, 106802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., Chai, J., & Cho, S. (2020). Deep learning in finance and banking: A literature review and classification. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 14(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. P., & Yen, M. F. (2019). A new perspective of performance comparison among machine learning algorithms for financial distress prediction. Applied Soft Computing Journal, 83, 105663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeur, S. B., Gharib, C., Mefteh-Wali, S., & Arfi, W. B. (2021). CatBoost model and artificial intelligence techniques for corporate failure prediction. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 166, 120658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenetey, G., & Popesko, B. (2024). Budgetary control and the adoption of consortium blockchain monitoring system in the Ghanaian local government. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 38(1), 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Cho, H., & Ryu, D. (2020). Corporate default predictions using machine learning: Literature review. Sustainability, 12(16), 6325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristanti, F. T., Febrianta, M. Y., Salim, D. F., Riyadh, H. A., Sagama, Y., & Beshr, B. A. H. (2024). Advancing financial analytics: Integrating XGBoost, LSTM, and random forest algorithms for precision forecasting of corporate financial distress. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(8), 4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kureljusic, M., & Karger, E. (2024). Forecasting in financial accounting with artificial intelligence—A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 25(1), 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecun, Y., Bengio, Y., & Hinton, G. (2015). Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553), 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J., Jang, D., & Park, S. (2017). Deep learning-based corporate performance prediction model considering technical capability. Sustainability, 9(6), 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., & Sun, Z. (2023). Application of deep learning in recognition of accrued earnings management. Heliyon, 9(3), E13664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Crook, J., & Andreeva, G. (2014). Chinese companies distress prediction: An application of data envelopment analysis. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 65(3), 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W. C., & Tsai, C. F. (2020). Missing value imputation: A review and analysis of the literature (2006–2017). Artificial Intelligence Review, 53(2), 1487–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanchian, M. (2024). Generative AI for consumer behavior prediction: Techniques and applications. Sustainability, 16(22), 9963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manogna, R. L., & Mishra, A. K. (2021). Measuring financial performance of Indian manufacturing firms: Application of decision tree algorithms. Measuring Business Excellence, 26(3), 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moubarak, H. M. R. (2024). Detecting the probability of fraud in interim financial statements using machine learning models: Do correlation-based analysis and principal component analysis for dimensionality reduction matter? Alexandria Journal of Accounting Research, 8(3), 87–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, G. A., Elamir, E. A. H., & Hussainey, K. (2022). Using machine learning methods to predict financial performance: Does disclosure tone matter? International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 19(1), 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M. A., Gomaa, I. I., Moubarak, H., & Sabry, S. H. (2025). Predicting corporate financial performance in artificial intelligence era: A comprehensive bibliometric study. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/jfra/article-abstract/doi/10.1108/JFRA-11-2024-0891/1262454/Predicting-corporate-financial-performance-in?redirectedFrom=fulltext (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Ozbayoglu, A. M., Gudelek, M. U., & Sezer, O. B. (2020). Deep learning for financial applications: A survey. Applied Soft Computing Journal, 93, 106384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, M., Ylinen, M., & Järvenpää, M. (2023). Machine learning in management accounting research: Literature review and pathways for the future. European Accounting Review, 32(3), 607–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickert, C. A., Henkel, M., & Lieleg, O. (2023). An efficiency-driven, correlation-based feature elimination strategy for small datasets. APL Machine Learning, 1(1), 016105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riskiyadi, M. (2024). Detecting future financial statement fraud using a machine learning model in Indonesia: A comparative study. Asian Review of Accounting, 32(3), 394–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundo, F., Trenta, F., di Stallo, A. L., & Battiato, S. (2019). Machine learning for quantitative finance applications: A survey. Applied Sciences, 9(24), 5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, S. H., & Ibrahim, Y. (2024). Machine learning on trial: Assessing its efficacy in detecting financial statement fraud. International Journal of Auditing and Accounting Studies, 6(2), 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T., & Rehmsmeier, M. (2015). The precision-recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced datasets. PLoS ONE, 10(3), e0118432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, I. H. (2022). AI-based modeling: Techniques, applications and research issues towards automation, intelligent and smart systems. SN Computer Science, 3(2), 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidhuber, J. (2015). Deep learning in neural networks: An overview. Neural Networks, 61, 85–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, S. N., Ismail, N., & Nur-Firyal, R. (2023). Life insurance prediction and its sustainability using machine learning approach. Sustainability, 15(13), 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S., Musa, M., & Brédart, X. (2022). Bankruptcy prediction using machine learning techniques. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(1), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, M., & Lapalme, G. (2009). A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Information Processing and Management, 45(4), 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H., Hyun, C., Phan, D., & Hwang, H. J. (2019). Data analytic approach for bankruptcy prediction. Expert Systems with Applications, 138, 112816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S. M., Kaymak, U., & Sousa, J. M. C. (2010, July 18–23). Cohen’s kappa coefficient as a performance measure for feature selection. 2010 IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence, WCCI 2010, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J. C., Xie, F., Zhang, Y., & Caulfield, C. (2013). Artificial intelligence and data mining: Algorithms and applications. Abstract and Applied Analysis, 2013, 524720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., & Wang, H. (2025). Random forest-based machine failure prediction: A performance comparison. Applied Sciences, 15(16), 8841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, Z. M., Ali, Z. H., Salih, S. Q., & Al-Ansari, N. (2020). Prediction of risk delay in construction projects using a hybrid artificial intelligence model. Sustainability, 12(4), 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, X. (2019). An overview of overfitting and its solutions. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1168(2), 022022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaini, B. J., & Mahmuddin, M. (2019). Classifying firms’ performance using data mining approaches. International Journal of Supply Chain Management, 8(1), 690–696. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B., Shi, H., & Wang, H. (2023). Machine learning and AI in cancer prognosis, prediction, and treatment selection: A critical approach. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 16, 1779–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W., Cao, Q., & Schniederjans, M. J. (2004). Neural network earnings per share forecasting models: A comparative analysis of alternative methods. Decision Sciences, 35(2), 205–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Ouenniche, J., & De Smedt, J. (2024). Survey, classification and critical analysis of the literature on corporate bankruptcy and financial distress prediction. Machine Learning with Applications, 15, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L., Lai, K. K., & Yen, J. (2014). Bankruptcy prediction using SVM models with a new approach to combine features selection and parameter optimisation. International Journal of Systems Science, 45(3), 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M., Liu, H., & Hu, Y. (2022). Research on corporate financial performance prediction based on self-organizing and convolutional neural networks. Expert Systems, 39(9), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Definitions | Data Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quick Ratio | (Current Assets − Inventory) ÷ Current Liabilities | Compustat | (Delen et al., 2013; Geng et al., 2015) |

| Debt-to-Equity Ratio | Total Debt ÷ Total Equity | Compustat | (Gajdosikova et al., 2024) |

| Return on Assets (ROA) | Net Income ÷ Total Assets | Compustat | (Delen et al., 2013; Z. Li et al., 2014) |

| Return on Equity (ROE) | Net Income ÷ Total Equity | Compustat | (Delen et al., 2013) |

| Working Capital Turnover | Sales ÷ (Current Assets − Current Liabilities) | Compustat | (Delen et al., 2013) |

| Current Assets Turnover | Sales ÷ Current Assets | Compustat | (Delen et al., 2013) |

| Fixed Assets Turnover | Sales ÷ Fixed Assets | Compustat | (Delen et al., 2013) |

| Assets Turnover | Sales ÷ Total Assets | Compustat | (Delen et al., 2013) |

| Equity Turnover | Sales ÷ Total Equity | Compustat | (Delen et al., 2013) |

| Operating Cash Flows Ratio | Operating Cash Flows ÷ Current Liabilities | Compustat | (Z. Li et al., 2014) |

| Operating Cash Flows to Interest | Operating Cash Flows ÷ Interest | Compustat | (Z. Li et al., 2014) |

| Operating Cash Flows to Total Assets | Operating Cash Flows ÷ Total Assets | Compustat | (Arora & Saurabh, 2022) |

| Short Term Debt Ratio | Current Liabilities ÷ Total Liabilities | Compustat | (Delen et al., 2013) |

| Inventory Turnover | COGS ÷ Average Inventory | Compustat | (Delen et al., 2013) |

| Operating Margin | EBIT ÷ Sales | Compustat | (Arora & Saurabh, 2022) |

| Country | Total Observations | Class A (0) | Class B (1) | Class C (2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saudi Arabia | 1747 | 579 | 572 | 596 |

| Egypt | 1526 | 504 | 501 | 521 |

| Jordan | 1173 | 390 | 382 | 401 |

| Kuwait | 922 | 309 | 300 | 313 |

| Oman | 808 | 270 | 261 | 277 |

| UAE | 629 | 210 | 206 | 213 |

| Morocco | 387 | 129 | 125 | 133 |

| Tunisia | 319 | 108 | 101 | 110 |

| Qatar | 269 | 91 | 84 | 94 |

| Bahrain | 191 | 62 | 60 | 69 |

| Total | 7971 | 2652 | 2592 | 2727 |

| Features | Mean | Std | Min | 25% | 50% | 75% | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quick Ratio | 2.244138 | 12.15191 | 0 | 0.642712 | 1.081713 | 1.880524 | 673.5 |

| Debt to Equity | 1.215335 | 11.4995 | −628.176 | 0.282101 | 0.697878 | 1.470877 | 584.7252 |

| Short-Term Debt Ratio | 0.699343 | 0.252202 | 0 | 0.51368 | 0.76055 | 0.919459 | 1.903832 |

| ROE | 0.044399 | 1.119285 | −50.3359 | 0.006718 | 0.071225 | 0.152326 | 39.15686 |

| ROA | 0.02497 | 0.224285 | −11.5648 | 0.000347 | 0.035413 | 0.078958 | 0.757847 |

| Operating Margin | −0.52777 | 17.53445 | −1017.25 | 0.005807 | 0.083638 | 0.18203 | 48.66667 |

| Asset Turnover | 0.625604 | 0.601206 | −0.7805 | 0.242694 | 0.501983 | 0.830838 | 13.1094 |

| Inventory Turnover | 78.00999 | 1248.304 | −49.2325 | 3.208888 | 6.310354 | 18.41748 | 62731.3 |

| Working Capital Turnover | 6.583517 | 656.9538 | −15931.1 | −0.00389 | 1.700715 | 4.180777 | 53928 |

| Current Assets Turnover | 1.59581 | 1.720355 | −4.96341 | 0.780757 | 1.268777 | 1.921866 | 70.66667 |

| Fixed Assets Turnover | 5.639975 | 274.4232 | −1.5226 | 0.359666 | 0.916303 | 2.238975 | 24403 |

| Equity Turnover | 1.462451 | 5.537002 | −206.216 | 0.361983 | 0.908203 | 1.734698 | 187.9949 |

| Operating CF Ratio | 0.451266 | 5.468825 | −152.463 | 0.026262 | 0.245525 | 0.63068 | 361.7 |

| Operating CF to Total Assets | 0.065632 | 0.16278 | −9.96545 | 0.008632 | 0.0608 | 0.121155 | 1.336859 |

| Operating CF to Interest | 85.33023 | 1746.904 | −31722 | 0.866035 | 4.967742 | 18.86171 | 108923 |

| Feature | VIF | Feature | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Debt to Equity | 4.049229706 | Operating Margin | 1.031507546 |

| ROE | 2.893773344 | Operating CF Ratio | 1.026062391 |

| Equity Turnover | 2.033905781 | Quick Ratio | 1.019462332 |

| Asset Turnover | 1.602556387 | Fixed Assets Turnover | 1.008773601 |

| ROA | 1.547796170 | OCF Interest | 1.005475928 |

| OCF TA | 1.520446235 | Inventory Turnover | 1.001390774 |

| Current Assets Turnover | 1.316247099 | Working Capital Turnover | 1.000371071 |

| Short-Term Debt Ratio | 1.134683447 |

| Algorithm | Overall Accuracy | Overall Error | Cohen’s Kappa | Correctly Classified | Incorrectly Classified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFs | 0.735589 | 0.264411 | 0.603389 | 587 | 211 |

| XGBoost | 0.754386 | 0.245614 | 0.631639 | 602 | 196 |

| SVMs | 0.680451 | 0.319549 | 0.521528 | 543 | 255 |

| DNNs | 0.720551 | 0.279449 | 0.580633 | 575 | 223 |

| Classes | Algorithm | True Positives | False Positives | True Negatives | False Negatives | Type I Error | Type II Error | Recall or Sensitivity | Precision | Specificity | F Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class A | RFs | 198 | 23 | 509 | 83 | 0.043 | 0.256 | 0.744 | 0.896 | 0.957 | 0.813 |

| XGBoost | 200 | 22 | 510 | 66 | 0.041 | 0.248 | 0.752 | 0.901 | 0.959 | 0.819 | |

| SVMs | 183 | 25 | 507 | 83 | 0.047 | 0.312 | 0.687 | 0.879 | 0.953 | 0.772 | |

| DNNs | 196 | 28 | 504 | 70 | 0.053 | 0.263 | 0.737 | 0.875 | 0.947 | 0.800 | |

| Class B | RFs | 174 | 115 | 424 | 85 | 0.213 | 0.328 | 0.672 | 0.602 | 0.786 | 0.635 |

| XGBoost | 185 | 108 | 431 | 74 | 0.200 | 0.286 | 0.714 | 0.631 | 0.799 | 0.670 | |

| SVMs | 183 | 166 | 373 | 76 | 0.308 | 0.293 | 0.706 | 0.524 | 0.692 | 0.602 | |

| DNNs | 161 | 112 | 427 | 98 | 0.208 | 0.378 | 0.622 | 0.589 | 0.792 | 0.605 | |

| Class C | RFs | 215 | 73 | 452 | 58 | 0.139 | 0.212 | 0.787 | 0.746 | 0.861 | 0.766 |

| XGBoost | 217 | 66 | 459 | 56 | 0.126 | 0.205 | 0.795 | 0.767 | 0.874 | 0.781 | |

| SVMs | 177 | 64 | 461 | 96 | 0.122 | 0.352 | 0.648 | 0.734 | 0.878 | 0.689 | |

| DNNs | 218 | 83 | 442 | 55 | 0.158 | 0.201 | 0.799 | 0.724 | 0.842 | 0.759 |

| Model | ROC-AUC Macro | ROC-AUC Micro | AP Macro | AP Micro |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFs | 0.906639 | 0.912199 | 0.827222 | 0.84518 |

| XGBoost | 0.9056 | 0.911213 | 0.822428 | 0.843206 |

| SVMs | 0.858428 | 0.869536 | 0.743314 | 0.776952 |

| DNNs | 0.865629 | 0.879947 | 0.739238 | 0.789038 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Omar, M.A.; Gomaa, I.I.; Sabry, S.H.; Moubarak, H. Artificial Intelligence’s Role in Predicting Corporate Financial Performance: Evidence from the MENA Region. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2026, 19, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010051

Omar MA, Gomaa II, Sabry SH, Moubarak H. Artificial Intelligence’s Role in Predicting Corporate Financial Performance: Evidence from the MENA Region. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2026; 19(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmar, Mayar A., Ismail I. Gomaa, Sara H. Sabry, and Hosam Moubarak. 2026. "Artificial Intelligence’s Role in Predicting Corporate Financial Performance: Evidence from the MENA Region" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 19, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010051

APA StyleOmar, M. A., Gomaa, I. I., Sabry, S. H., & Moubarak, H. (2026). Artificial Intelligence’s Role in Predicting Corporate Financial Performance: Evidence from the MENA Region. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 19(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010051