1. Introduction

The Asia Pacific is the world’s largest contributor to carbon emissions, largely driven by ASEAN economies (

International Energy Agency, 2023). Despite the region’s heavy reliance on natural resources (

Du et al., 2024;

Nathaniel, 2021;

C. Tang et al., 2022), corporate transparency regarding environmental impact remains critically low. According to the LSEG Refinitiv database, only approximately 13% of publicly listed companies in ASEAN-5 disclosed carbon emissions data in 2022. This lack of transparency stems from the sensitive nature of carbon data; while withholding information risks legitimacy (

Zhou et al., 2018), disclosing high emissions exposes firms to reputational damage and perceptions of being polluters (

Kanashiro, 2020;

Zhao et al., 2020).

This dilemma is exacerbated by the unique regulatory landscape of ASEAN-5. While Sustainability Reporting (SR) has become mandatory across the region, Sustainability Assurance (SA) remains largely voluntary (

PwC, 2024). This creates a “credibility gap” where management possesses significant discretion over the quality of disclosures. Unlike developed markets (e.g., EU or US) where assurance practices are mature and often mandatory (

Rohani et al., 2023), ASEAN is characterized as an emerging market with an SA framework dominated by limited assurance engagements. Within this context, it remains unclear whether voluntary SA functions effectively as a transparency signal or merely as a symbolic gesture. Therefore, this study aims to examine the relationship between the adoption of voluntary SA and carbon disclosure transparency in ASEAN-5, specifically investigating whether external verification can mitigate information asymmetry in an emerging market characterized by high managerial discretion.

Theoretically, this study leverages the tension between Stakeholder and Agency perspectives. Stakeholder theory suggests firms disclose emissions to maintain trust (

Farooq et al., 2024;

Freeman, 1984). Conversely, Agency theory warns that managers may manipulate or withhold adverse carbon data to protect their interests (

Zhao et al., 2020). We posit that SA serves as a critical bonding mechanism to resolve this tension. By voluntarily incurring the cost of external assurance (

Haider & Nishitani, 2020), firms signal a credible commitment to accountability (

Farooq et al., 2024), employing auditors to verify and “filter” data, thereby reducing information asymmetry and ensuring disclosures reflect actual performance rather than greenwashing (

C. Qian et al., 2015;

Simnett, 2012). This improvement in carbon disclosure transparency is realized through the combined incentives of the firm (seeking verification and market differentiation) (

Farooq et al., 2024;

Issa, 2025b;

W. Qian et al., 2018;

Ruiz-Barbadillo & Martínez-Ferrero, 2022) and the auditor (motivated by reputational risk and the avoidance of complicity in greenwashing) (

Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2020;

Harrer & Lehner, 2024;

Martínez-Ferrero et al., 2018;

Tran & Tran, 2023).

To test this conjecture, we analyzed 875 firm-year observations from ASEAN-5 listed companies (2018–2022). We measure carbon disclosure transparency using the magnitude of disclosed Total Carbon, Scope 1, and Scope 2 emissions. Utilizing a panel regression model with several robustness tests, we find that SA adoption has a positive relationship with higher carbon disclosure transparency. Specifically, SA adoption leads to significantly higher disclosure magnitudes across all scopes of emissions. Additional analyses reveal that this relationship is more pronounced among firms with high environmental performance and greater property, plant, and equipment (PPE) efficiency—indicating that SA adoption aligns with genuine sustainability efforts. We also find that firms with SA are more likely to disclose the complex Scope 3 emissions. Furthermore, the effectiveness of SA in enhancing transparency is conditional, showing statistical significance only within the mandatory sustainability reporting (SR) regimes and in non-environmentally sensitive industries, suggesting that a regulatory backbone is crucial for assurance effectiveness in ASEAN.

This study makes three distinct contributions to the literature. First, it bridges a significant contextual gap. Prior studies have predominantly focused on developed economies with mature assurance markets (e.g.,

Issa, 2025a;

Luo et al., 2023;

Rohani et al., 2023). This study provides novel evidence from ASEAN-5, demonstrating that even in an emerging market dominated by limited assurance engagements, voluntary SA successfully functions as a transparency mechanism. Second, we extend the audit literature by validating the role of non-financial assurance as a strategic tool for risk management. We show that firms leverage SA to differentiate themselves, while also extending transparency to complex Scope 3 emissions. Third, our findings enrich Agency Theory in developing economies. We confirm that voluntary assurance reduces information asymmetry not by enforcing compliance, but by signaling “true” environmental risk exposure, validated by the finding that high-performing firms are the primary drivers of this transparency.

Moreover, this study presents several practical implications. For corporate managers, adopting SA is a strategic decision that strengthens the credibility of carbon emissions disclosures, particularly when facing heightened scrutiny in global supply chains. For firms with high emissions or superior environmental performance, SA can be utilized as a tool for risk management and differentiation by validating the true extent of their environmental footprint. For policymakers and regulators in ASEAN-5, our findings underscore that making Sustainability Reporting mandatory is only the first step; to ensure the quality and transparency of disclosures, regulatory frameworks should actively incentivize or transition toward mandatory SA. This is especially relevant as the region moves toward the adoption of global standards like IFRS S1 and S2, where SA quality is paramount for promoting transparency and comparability. Finally, for investors and stakeholders, the study provides assurance adoption as a verifiable signal of corporate transparency and commitment, helping them distinguish between firms genuinely dedicated to climate action and those engaging in greenwashing.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 details the theoretical framework and hypotheses.

Section 3 outlines the research methodology.

Section 4 presents the empirical results and discussion. Finally,

Section 5 concludes with implications and limitations.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Sustainability Reporting in ASEAN-5

Although the ASEAN comprises developing economies, the region is a significant contributor to global carbon emissions (

International Energy Agency, 2023). The relationship between economic development and environmental impact here is complex;

Arslan et al. (

2022),

Nathaniel and Khan (

2020), and

Nathaniel (

2021) argue that, unlike in developed nations (

Alola et al., 2019), rapid economic growth in the ASEAN often parallels environmental degradation. Consequently, the regulatory landscape of sustainability reporting remains in a developing stage with varying progress (

PwC, 2024).

ASEAN-5 countries have progressively introduced mandatory Sustainability Reporting (SR). Malaysia (2016) and Singapore (2017) were early adopters, followed by the Philippines (2019), Indonesia (2020), and Thailand (2021 (

PwC, 2024)). The 2023 introduction of IFRS S1 and S2 by the ISSB adds urgency, requiring enhanced transparency. However, SA remains voluntary, despite the region’s reliance on natural resources (

Du et al., 2024;

C. Tang et al., 2022) and contribution to air pollution (

Firdaus et al., 2023). Given the gap between mandatory reporting and voluntary assurance, examining whether voluntary SA enhances carbon disclosure transparency is critical.

2.2. Sustainability Assurance Practices

SA serves as an external mechanism for verifying and validating non-financial information—particularly sustainability reporting—to enhance the credibility and reliability of the disclosed data (

Farooq et al., 2024;

Velte, 2025a). By subjecting reports to external scrutiny, SA increases the confidence of both managers and external stakeholders regarding the quality of sustainability performance data, thereby facilitating more informed decision-making (

Hassan et al., 2020).

However, unlike financial auditing, SA operates within a largely unregulated framework, particularly in voluntary regimes like ASEAN. This environment grants management significant flexibility (managerial discretion) to determine the parameters of the assurance engagement (

Ruiz-Barbadillo & Martínez-Ferrero, 2022). Managers are free to select the assurance provider, which creates a diverse market comprising accounting firms—who typically apply financial audit methodologies and quantitative verification—and non-accounting consultants, who often use evaluative approaches focusing on business systems (

Farooq & De Villiers, 2019;

Wong et al., 2016). Furthermore, management determines the standard used (typically ISAE 3000 or AA1000AS), the scope of assurance (ranging from single indicators to full report coverage), and the level of assurance (

Ruiz-Barbadillo & Martínez-Ferrero, 2022). Regarding the level of assurance, practices vary significantly. Engagements generally fall into three categories: reasonable assurance (high level), limited assurance, or moderate assurance. Consequently, in the ASEAN context, where SA is voluntary, the practice is characterized by this heterogeneity and is predominantly dominated by limited assurance engagements rather than reasonable assurance.

2.3. Prior Research and Contextual Gap

Recent literature has documented the role of SA in enhancing environmental disclosure quality, yet a significant contextual gap remains regarding its application in emerging markets.

Luo et al. (

2023), using a global dataset of the largest listed companies reporting to the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) from 2010–2020, found that SA improves carbon disclosure quality. They posit that SA serves as a monitoring tool where any omissions or errors identified by the provider trigger a comprehensive review and subsequent correction. Similarly,

Rohani et al. (

2023), focusing on US companies (2012–2017), found that a higher level of assurance (reasonable assurance) is required to significantly increase carbon performance. In the European context,

Issa (

2025a) highlights that mature assurance practices provide feedback to improve reliability.

However, these studies predominantly focus on developed markets (Global, US, Europe) where assurance practices are more mature and often mandatory. In such environments, the debate often shifts to the level of assurance (limited vs. reasonable). In contrast, as highlighted in

Section 2.2, ASEAN-5 is unique: it is an emerging region where SA is voluntary and dominated by limited or moderate assurance. Unlike

Rohani et al. (

2023), whose findings rely on reasonable assurance, this study investigates whether the adoption of voluntary SA (mostly limited/moderate) is sufficient to signal transparency in an environment marked by high managerial discretion. This study fills the gap by examining SA as a voluntary credibility signal rather than a regulatory compliance mechanism.

2.4. Sustainability Assurance and Carbon Disclosure Transparency

This study draws upon Stakeholder Theory and Agency Theory to explain the potential relationship between the adoption of SA and carbon disclosure transparency. Stakeholder Theory posits that firms must consider the interests of both shareholders and other stakeholders, who demand transparency and reliability in sustainability reporting (

Freeman, 1984). Corporate transparency emphasizes that reporting should accurately reflect reality rather than be manipulated to serve specific interests (

Parris et al., 2016), and firms are expected to disclose carbon emissions to maintain legitimacy (

Gaio et al., 2022;

Reid et al., 2024). Recent research in emerging economies further suggests that robust governance mechanisms are essential to drive this sustainability (

Abdalla et al., 2024,

2025;

Adam et al., 2025;

Fransisca et al., 2025;

Jin et al., 2025). A firm’s commitment to carbon transparency reflects its intent to ensure that disclosures are clear, credible, and reliable (

Kim, 2014;

Millar et al., 2005).

However, from an Agency perspective, reporting high carbon emissions may lead to negative consequences, as firms with high emissions are often perceived as highly polluting (

Kanashiro, 2020;

Zhao et al., 2020). This creates an incentive for managers to limit carbon disclosure to protect their interests, leading to information asymmetry. Agency Theory posits that SA, as an external monitoring mechanism, mitigates this asymmetry by aligning disclosed information with actual performance (

C. Qian et al., 2015;

Simnett, 2012).

From the client’s perspective, SA is adopted to enhance reliability (

Ruiz-Barbadillo & Martínez-Ferrero, 2022). By voluntarily bearing the additional costs of SA (

Haider & Nishitani, 2020), firms demonstrate their commitment to sustainability (

Farooq et al., 2024). Crucially, SA enhances transparency through verification and correction. As noted by

Luo et al. (

2023), assurance providers act as an independent filter; interactions with them force managers to correct errors or omissions before publication (

Issa, 2025a). In a voluntary regime, firms without assurance may strategically “greenwash” by suppressing high emission figures. Therefore, when a firm adopts SA, the subsequent reporting of higher emissions indicates transparency (revealing true environmental impact) rather than poor performance. Additionally, firms use SA for benchmarking (

W. Qian et al., 2018) to communicate comparable information (

Prajogo et al., 2016), attracting investors (

Appiagyei et al., 2023) and enhancing value (

Kuzey et al., 2023;

Velte, 2025b).

Complementing this, auditors in ASEAN-5 are motivated to enhance transparency to protect their reputation, particularly large firms (

Martínez-Ferrero et al., 2018;

Tran & Tran, 2023) and to avoid litigation risks associated with greenwashing scandals (

Asante-Appiah & Lambert, 2023). Thus, auditors enforce high-quality disclosures to avoid complicity (

Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2020;

Harrer & Lehner, 2024), providing a market advantage for practitioners promoting credible practices (

Fernandez-Feijoo et al., 2016).

Taken together, considering the ASEAN context (voluntary assurance) and the motivations of both firms (verification) and auditors (risk avoidance), SA emerges as a critical mechanism to reduce information asymmetry. It functions not as a compliance tick-box, but as a tool that forces the revelation of accurate carbon data. In light of these theoretical arguments, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

Firms that adopt sustainability assurance (SA) are more transparent in disclosing carbon emissions.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

This study’s population consists of publicly listed companies from the ASEAN-5 countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand). These countries serve as the economic pillars of the ASEAN region due to their market size. However, despite their economic significance, they exhibit minimal carbon transparency while remaining highly dependent on natural resources (

Du et al., 2024;

Nathaniel, 2021;

C. Tang et al., 2022). Moreover, the environmental practice of this ASEAN region still lags behind European countries (

Shahzad et al., 2020). This data spans from 2018 to 2022, aligning with the ratification of the Paris Agreement in 2016, which was adopted by the ASEAN-5 countries between 2016 and 2017.

To construct the final sample, we applied specific selection criteria based on data availability across multiple databases. First, companies must be listed on their national exchanges and have available Carbon emissions data in the LSEG Refinitiv database. Second, they must have complete financial data in the Osiris database and governance characteristics in Bloomberg. Country-level macroeconomic indicators were retrieved from the World Bank. Additionally, data on SA were manually hand-collected from annual and sustainability reports. We eliminated observations with missing values for carbon emissions from LSEG Refinitiv, as well as those without annual or sustainability reports, and those with missing data for other variables across the referenced databases. The final sample consists of 294 unique firms, resulting in 875 firm-year observations.

Table 1 presents the sample distribution of this study.

3.2. Data and Variables

The dependent variable in this study is Carbon Disclosure Transparency. Unlike studies in mature markets that utilize CDP scores (e.g.,

Luo et al., 2023;

Rohani et al., 2023), relying on such scores in the ASEAN context is problematic due to limited coverage, which biases the sample toward only the largest multinationals. Given the nascent stage of reporting in this region, transparency is best captured by the actual disclosure of emission magnitudes. In a voluntary regime prone to data suppression (greenwashing), higher disclosed emissions signal transparency by revealing actual climate risk exposure rather than withholding it (

Parris et al., 2016;

C. Qian et al., 2015).

Accordingly, we measure transparency using the natural logarithm of carbon emissions (

Khatri, 2024;

Muttakin et al., 2022). The emission data (CO2 equivalent) is retrieved from the LSEG Refinitiv database and encompasses carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, hydrofluorocarbons, and sulphur hexafluoride. To provide a robust analysis, we operationalize this variable through three distinct metrics: Total Carbon (Scope 1 + 2), Direct Carbon (Scope 1), and Indirect Carbon (Scope 2). We focus on these scopes because, as emphasized by

Rohani et al. (

2023), they serve as the essential overall indicator of corporate carbon responsibility. Furthermore, separating these scopes is crucial due to their differing operational natures (

Hertwich & Wood, 2018). Scope 1 emissions represent direct emissions from operations (e.g., fuel combustion), requiring complex interventions in industrial processes and cleaner technology investments. In contrast, Scope 2 emissions arise from indirect sources like energy consumption, which are generally easier to manage through the purchase of cleaner energy (

Rankin et al., 2011;

Zhou et al., 2018). Recognizing these varying levels of management complexity, we utilize the natural logarithm of each metric (Total, Scope 1, and Scope 2) to capture the depth of corporate transparency.

The independent variable of this study, SA, is a dichotomous variable, with a value of 1 if the firm’s sustainability or annual report is audited by independent third-party assurance and zero otherwise (

Braam et al., 2016;

Ruiz-Blanco et al., 2022). We manually gathered the SA data from sustainability and/or annual reports.

Our study incorporates several control variables. First, firm-specific characteristics are included: firm size is measured as the natural logarithm of total assets as larger firms are associated with greater commitment to carbon transparency (

Clarkson et al., 2008); profitability is measured by the return on assets ratio (PROFIT), equity market value is measured by the equity market-to-book ratio (MTB), and leverage is measured by the debt-to-assets ratio (LEV) are more likely to prioritize financial performance over environmental commitments (

Haque, 2017). These financial control variables were obtained from the Osiris database. Second, governance characteristics are considered, including board size, the percentage of independent directors, and the percentage of institutional ownership, that retrieved from the Bloomberg database. An independent board tends to be more environmentally transparent and committed to carbon reduction initiatives (

Haque, 2017). Lastly, to account for country-specific factors, we control for economic size and reporting quality that may influence the carbon emissions, measured by each country’s annual gross domestic product (GDP) and regulatory quality (REGULATOR), retrieved from the World Bank database.

3.3. Model Specifications

To examine our hypothesis, we employ a panel regression with firm-clustered robust standard errors, which appropriately accounts for time-invariant unobservable firm characteristics, heteroscedasticity, and within-firm serial correlation, while year and industry fixed effects absorb macroeconomic and sectoral heterogeneity. The regression model is presented in Equation (1):

Equation (1) shows the relationship between sustainability assurance () and the vector EMISSIONS variable comprising total carbon (), scope 1 emissions (), and scope 2 emissions (). The control variables include firm size (), profitability (), leverage (), equity market-to-book (), board size (), percentage of independent board (), and percentage of institutional ownership (). Meanwhile, and serve as country-specific controls, accounting for macroeconomic conditions. Additionally, and are included to control for industrial and time-specific effects.

In addition, to ensure that our results are not sensitive to model assumption and to address potential endogeneity related to SA, we conduct several robustness analyses, including Propensity Score Matching (PSM) to reduce selection bias, Instrumental Variable Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) using an external instrument to mitigate simultaneity and omitted-variable concerns, System Generalized method of moments (GMM), and dynamic analysis to incorporate dynamic emissions behavior and further correct for endogeneity arising from unobserved heterogeneity or reverse causality.

4. Result and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 (Panel A) summarizes the descriptive statistics for the main variables. The natural logarithm of total carbon emissions has a mean of 11.78, corresponding to approximately 1.84 million metric tons of CO2e. Scope 1 (direct) and Scope 2 (indirect) emissions show natural-log means of 9.877 and 10.609, respectively. As illustrated in

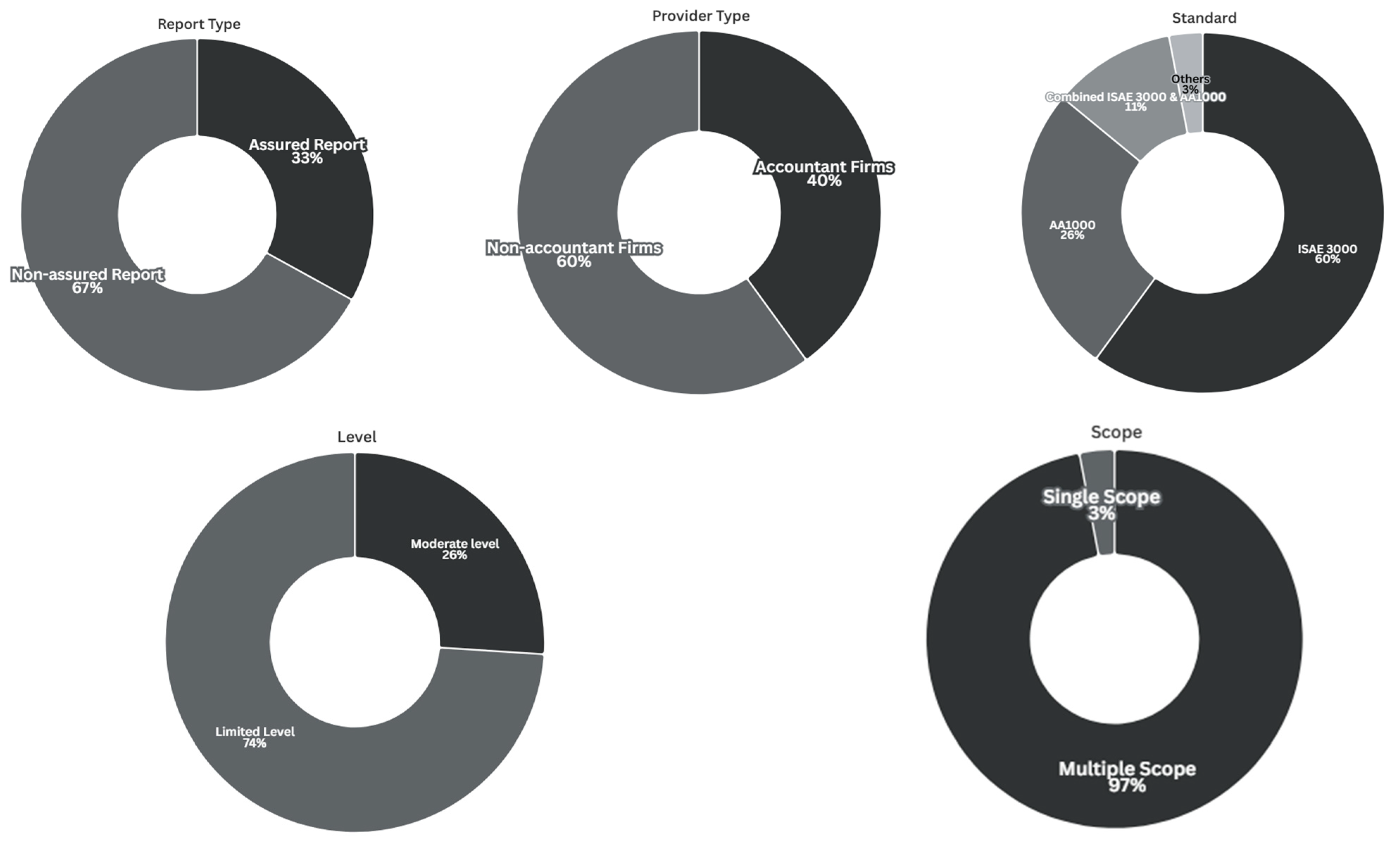

Figure 1, approximately 33% of the sampled firms (289 observations) voluntarily obtain SA. The assurance market is dominated by non-accounting providers (60%), with ISAE 3000 being the prevailing standard (60%). Notably, the majority of engagements (74%) provide a limited level of assurance covering multiple scopes (97%).

The correlation matrix in

Table 3 indicates a significant positive correlation between SA and all carbon emission metrics (CARBON, SCOPE1, SCOPE2), suggesting that assured firms tend to disclose higher emission magnitudes. Multicollinearity is not a concern, as correlation coefficients generally remain below 0.5, and all variance inflation factors (VIF) reported in

Table 2 are well below the threshold of 5. Additionally, the independent

t-test results in

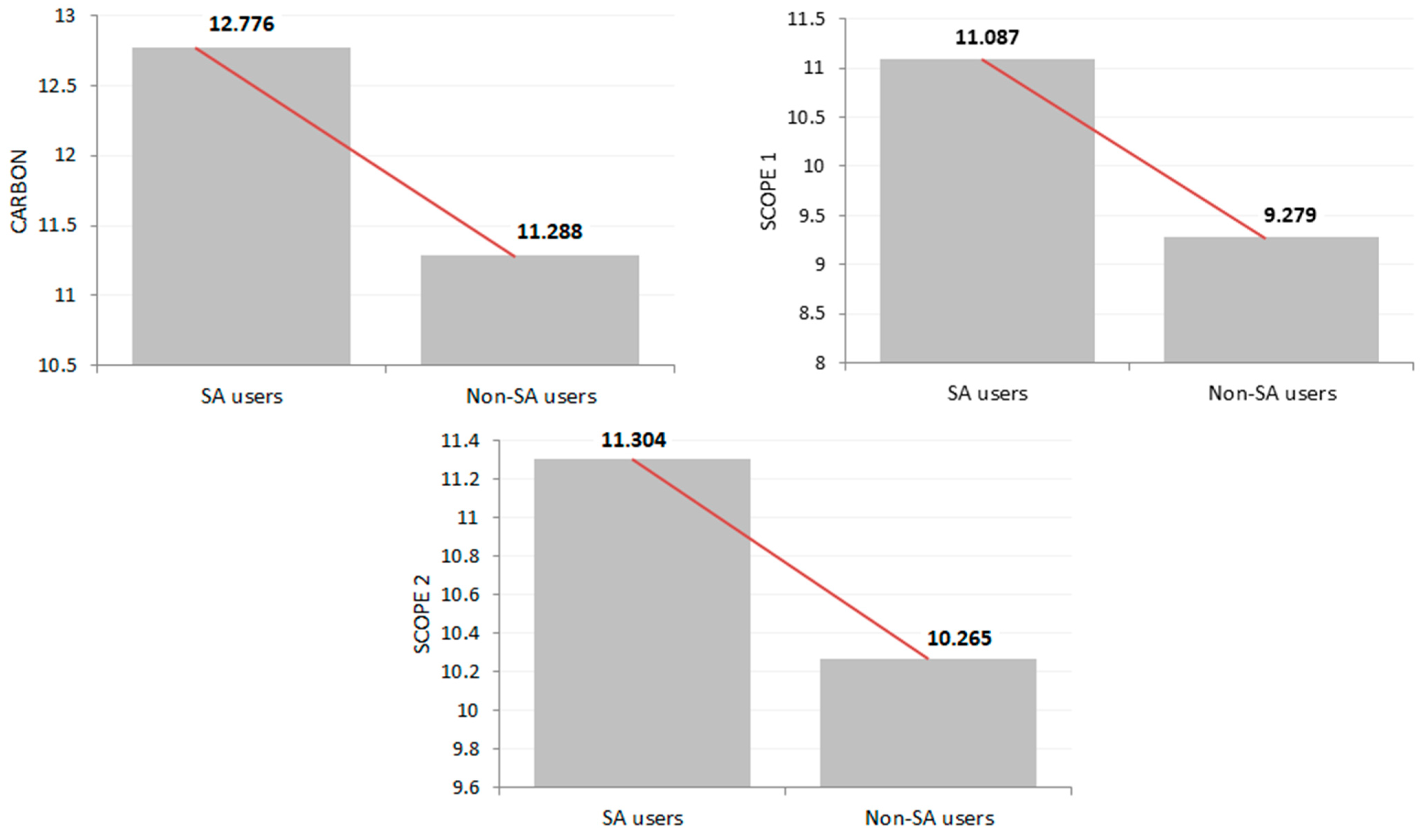

Figure 2 confirm that SA adopters report significantly higher carbon emissions (mean = 12.776) compared to non-adopters (mean = 11.288) at the 1% significance level, preliminarily supporting the notion that assurance encourages the revelation of carbon data.

4.2. Main Regression Result: SA and Carbon Disclosure Transparency

Table 4 presents the regression results examining the relationship between SA and carbon disclosure transparency, as specified in Equation (1). As shown in Column (1), SA is positively associated with overall carbon disclosure (CARBON) with a coefficient of 0.570, significant at the 1% level. This positive relationship is consistent across emission scopes; Columns (2) and (3) confirm significant positive coefficients for Scope 1 (

= 0.793,

p < 0.01) and Scope 2 (

= 0.700,

p < 0.01) emissions. These findings indicate that firms adopting voluntary assurance are more likely to disclose greater magnitudes of carbon information. Specifically, they actively measure and report emissions from fuel combustion and industrial processes (Scope 1) as well as purchased electricity (Scope 2). This comprehensive reporting reflects a commitment to detailed transparency (

Hertwich & Wood, 2018), thereby supporting our hypothesis.

Regarding control variables, firm size (SIZE), board size (BOARD), and GDP exhibit a positive and significant relationship with transparency, suggesting that larger, well-governed firms in stronger economies face higher disclosure pressures. The model demonstrates a robust fit, explaining up to 48.5% of the variation in total carbon (Adjusted R2 = 0.485). To ensure the reliability of these estimates, all regressions include Industry and Year Fixed Effects to control for unobserved heterogeneity and utilize standard errors clustered at the firm level to mitigate potential heteroscedasticity and serial correlation.

The positive relationship between SA and disclosed emissions supports Agency Theory (

C. Qian et al., 2015;

Simnett, 2012), implying that external verification functions effectively to reduce information asymmetry even in a voluntary setting. By subjecting carbon reports to third-party scrutiny, firms signal a commitment to revealing actual climate risks rather than obscuring them. Simultaneously, the results align with Stakeholder Theory, which emphasizes that firms respond to stakeholder expectations by disclosing carbon emissions more transparently to maintain legitimacy and trust (

Farooq et al., 2024). SA thus signals accountability and environmental responsibility, serving as a credibility bridge between management and diverse stakeholders in the ASEAN-5 voluntary regime.

This finding is particularly meaningful given the unique context of emerging markets. While rapid economic growth in ASEAN often parallels environmental degradation (

Arslan et al., 2022;

Nathaniel & Khan, 2020), our results indicate that governance mechanisms like SA can disrupt this negative cycle. This aligns with recent empirical evidence from emerging economies, which suggests that robust governance mechanisms are the primary driver of sustainability commitment (

Abdalla et al., 2024,

2025;

Adam et al., 2025;

Fransisca et al., 2025;

Jin et al., 2025). Furthermore, considering that our sample is dominated by limited (74%) and moderate (26%) assurance with no observations of reasonable assurance, these findings suggest that the highest level of assurance is not a prerequisite for enhanced transparency in nascent markets. Instead, the adoption of even limited assurance acts as a sufficient bonding mechanism to improve disclosure credibility, allowing firms—especially those in high-risk sectors—to manage reputational concerns and differentiate themselves in the global supply chain.

4.3. Additional Analysis

4.3.1. Environmental Performance Heterogeneity

In the primary model, we document that companies adopting SA disclose higher carbon emissions. However, a potential concern is that this positive relationship might simply reflect poor environmental performance (i.e., heavy polluters are forced to disclose) rather than a genuine commitment to transparency. To address this bias, we re-estimated Equation (1) by partitioning the sample into two groups based on environmental performance. We conjecture that if SA truly signals transparency, the relationship should be more pronounced among firms with verified environmental commitments.

We utilize the Environmental Score from LSEG Refinitiv, which evaluates a firm’s effectiveness in reducing emissions and resource efficiency. The sample is classified into High and Low environmental performance groups based on the sample mean of 54.807 (see

Table 2, Panel B).

The results in

Table 5 largely support our conjecture. In the High Environmental Performance group, SA is positively and significantly associated with Total Carbon (Column 1;

= 0.359,

p < 0.05) and Scope 2 (Column 5;

= 0.680,

p < 0.01). This confirms that firms with established environmental credentials utilize SA to credibly signal their actual emissions profile, reinforcing their transparency to stakeholders.

Interestingly, we observe a different pattern for Scope 1 emissions. As shown in Column (4), SA has a positive and significant relationship with Scope 1 emissions only in the Low Environmental Performance group (

= 0.638,

p < 0.10), while the relationship is insignificant for the high-performing group (Column 3). This finding offers a nuanced insight: firms with poorer environmental performance may face heightened regulatory pressure regarding their direct operations (Scope 1). Consequently, they employ SA not to signal “greenness,” but as a risk management tool to verify that their high direct emissions are accurately measured and reported, thereby mitigating legitimacy threats. Nevertheless, the overall results remain consistent with our hypothesis. The fact that high-performing firms voluntarily report higher verified emissions validates that our transparency proxy captures honesty and accountability, not merely the scale of pollution (

Parris et al., 2016).

4.3.2. Operational Efficiency Analysis

While the previous analysis mitigates concerns regarding environmental performance, another potential confounding factor is operational scale. Critics might argue that higher disclosed emissions are simply a function of asset-heavy operations rather than transparency, given that Property, Plant, and Equipment (PPE) are major emission sources (

Fan et al., 2017). To rule out the possibility that our results are driven solely by operational intensity, we conducted a subsample analysis based on PPE efficiency.

We defined PPE efficiency as the ratio of sales to net PPE, classifying firms into High and Low efficiency groups relative to the sample mean. We posit that if SA reflects a genuine sustainability commitment, the positive relationship with disclosure should remain robust—or even be more pronounced—among firms that are operationally efficient.

The results in

Table 6 support this conjecture. In the High-PPE Efficiency group, SA exhibits a positive and statistically significant relationship with Total Carbon (Column 2;

= 0.537,

p < 0.01), Scope 1 (Column 4;

= 0.871,

p < 0.01), and Scope 2 emissions (Column 6;

= 0.567,

p < 0.01). Conversely, in the Low-PPE Efficiency group (Columns 1, 3, and 5), the coefficients for SA are statistically insignificant across all emission metrics.

This contrast is revealing. It suggests that the link between assurance and transparency is not an artifact of inefficient, asset-heavy operations. Instead, firms that optimize their asset utilization (High Efficiency) are the ones leveraging SA to transparently disclose their emissions. This reinforces the notion that SA adopters are proactive in managing their environmental impact through operational excellence (

Dong et al., 2022;

Xu et al., 2022), rather than merely reporting high emissions due to legacy inefficiencies.

4.3.3. Scope 3 Carbon Disclosure Analysis

In addition to Scope 1 and 2, firms are also increasingly expected to report Scope 3 emissions, which include indirect emissions from upstream and downstream activities in their supply chain, such as purchased goods, transportation, and product usage. Measuring Scope 3 emissions is inherently more difficult compared to Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions (

Blanco et al., 2016;

Hertwich & Wood, 2018;

Patchell, 2018), hence the disclosure is still limited. Our data show that only 418 out of 875 observations disclose Scope 3 emissions. To examine the consistency of our results, we include Scope 3 emissions in Equation (1) as the dependent variable and focus on the observations that disclose Scope 3 data. The result is shown in

Table 7.

Table 7 provides evidence that firms engaging in SA are more likely to disclose higher Scope 3 emissions (

= 0.728,

p < 0.05). This result suggests that SA plays a crucial role in encouraging firms to extend their carbon disclosure beyond direct operational emissions. Given that Scope 3 disclosure requires more comprehensive data collection and verification, firms with SA may be more committed to full-spectrum carbon accountability, reinforcing their sustainability transparency to stakeholders (

Datt et al., 2022;

Román et al., 2021). Unlike Scope 1 and Scope 2, which firms can control more directly, Scope 3 emissions are often spread across multiple entities within the supply chain. Thus, firms voluntarily reporting Scope 3 emissions—particularly those with SA—signal a higher level of commitment to sustainability governance and corporate responsibility (

Gaio et al., 2022;

Kim, 2014). Moreover, Stakeholder Theory suggests that firms engage in carbon transparency to meet investor, regulatory, and societal expectations. Given that Scope 3 emissions are increasingly scrutinized by regulators and sustainability-focused investors, firms using SA may view comprehensive disclosure as a strategic decision to enhance trust and legitimacy in sustainability markets (

Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2020;

Sánchez-Sancho et al., 2024).

4.3.4. Regulatory Regime Heterogeneity Analysis

To further investigate the drivers of transparency, we examine the moderating role of regulatory pressure. We partition the sample into Mandatory and Voluntary sustainability reporting (SR) regimes, as regulatory mandates may fundamentally alter the quality of disclosures and the function of assurance. Following the report by

PwC (

2024), we define the implementation years for mandatory SR across ASEAN-5 as follows: Indonesia (after 2020), Malaysia (after 2016), the Philippines (after 2019), Singapore (after 2017), and Thailand (after 2021). We hypothesize that in a mandatory environment, standardized reporting frameworks provide a stronger baseline for assurance providers to verify emissions, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of SA compared to a purely voluntary setting.

The results in

Table 8 reveal a striking contrast between the two regimes. While the coefficients for SA are positive across all specifications, statistical significance is exclusively concentrated in the Mandatory SR subsample. Specifically, under mandatory reporting, SA is positively and significantly associated with Total Carbon (Column 2;

= 0.550,

p < 0.01), Scope 1 (Column 4;

= 0.834,

p < 0.01), and Scope 2 (Column 6;

= 0.775,

p < 0.01). In contrast, the relationship is statistically insignificant in the voluntary regime (Columns 1, 3, and 5). This finding suggests that regulation acts as a necessary condition for assurance to function effectively. Consistent with

Alta’any et al. (

2025), who argue that national governance levels drive assurance practices, our results imply that mandatory reporting creates the institutional pressure and standardized environment required for SA to translate into credible, transparent carbon disclosure. Without the “backbone” of regulation, voluntary assurance alone appears less effective in driving statistically significant transparency improvements.

4.3.5. Environmentally Sensitive Industries Analysis

To further examine whether the relationship between SA and carbon transparency is contingent on industry context, we conduct a heterogeneity analysis by splitting the sample into environmentally sensitive and non-sensitive industries. Following (

Q. Tang & Luo, 2014), we classify environmentally sensitive industries as extractive sectors, specifically firms operating in Energy (GICS 1010), Materials (GICS 1510), and Utilities (GICS 5510). These sectors typically involve intensive resource extraction and high emissions, exposing them to heightened stakeholder scrutiny (

Ranängen & Zobel, 2014).

The subsample results reported in

Table 9 reveal a distinct divergence. For non-sensitive industries, SA is positively and significantly associated with transparency across all metrics (Columns 1, 3, and 5;

p < 0.01). In these sectors, where external environmental pressure is typically lower, engaging an assurance provider functions as a powerful differentiator, signaling superior credibility and commitment.

By contrast, in environmentally sensitive industries, the relationship between SA and both Total Carbon (Column 2) and Scope 1 (Column 4) is statistically insignificant. This lack of significance in the main emission categories suggests that for high-impact firms, the “proprietary cost” of transparency may outweigh the benefits of assurance during this emerging phase. As suggested by prior studies (

Darus et al., 2014;

Ryou et al., 2022), assurance in sensitive sectors might inadvertently reveal confidential operational details or expose the firm to excessive litigation risk by validating the sheer scale of their pollution. Consequently, environmentally sensitive firms may be hesitant to fully leverage SA for transparency regarding their complex direct operations (Scope 1).

However, a notable exception is found in Scope 2 emissions, where SA remains positively and significantly associated with transparency for both non-sensitive ( = 0.724, p < 0.01) and sensitive industries ( = 0.648, p < 0.05). This likely reflects the nature of Scope 2 emissions (purchased electricity), which are inherently easier to track, verify, and document compared to complex industrial processes. Thus, while sensitive firms may be cautious about transparently assuring their direct emissions (Scope 1), they appear willing to use SA to validate their indirect energy consumption, which poses lower proprietary risks and is technically easier to audit.

4.4. Robustness Check

4.4.1. Propensity Score Matching Method (PSM)

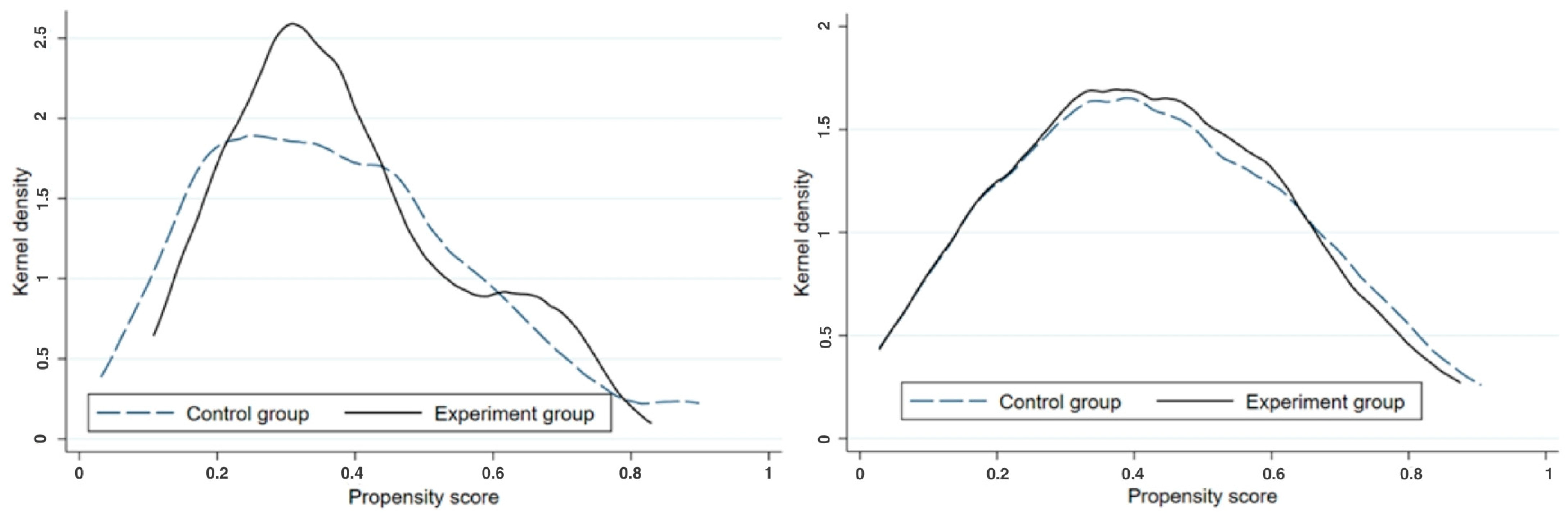

Our study may be subject to endogeneity issues, such as self-selection bias and omitted variable bias. To address potential unobservable factors influencing carbon emissions, we employ propensity score matching (PSM) to match SA users and non-SA users by 1:1 (177 observations per group).

Table 10 Panel A shows that the matched sample has similar characteristics across all control variables and eliminates unobservable factors that may influence the tendency to use SA and emissions level.

Table 10 Panel B shows that SA adoption remains positively associated with carbon emissions disclosure, reinforcing the robustness of our findings against self-selection bias.

Figure 3 is a plot of propensity score kernel density before and after matching, with significantly smaller differences between the matched treatment and control groups. In other words, our results are not confounded by unobservable factors that affect both the use of SA and carbon emissions.

4.4.2. Instrumental Variable (IV) Method

Additionally, we use two-stage least squares (2SLS) to address omitted variable bias. In the first stage, SA adoption is regressed with a probit model on IND_SA (the percentage of industry-wide SA adopters), which is positively and significantly associated with SA, confirming its relevance as an instrument variable (see

Table 11, Column 1). Using the first-stage estimates, we generate the predicted SA values and substitute them for SA in Equation (1) during the second stage. The results show that SA (Predicted) remains positively associated with CARBON, SCOPE1, and SCOPE2 (

Table 11, Columns 2, 3, and 4). Therefore, our results are unlikely to be driven by omitted variable bias.

4.4.3. Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) Estimation

To address potential endogeneity and reverse causality, we employ the generalized method of moments (GMM) estimator, which effectively accounts for dynamic relationships by using lagged dependent variables as instruments. Given the persistence of carbon emissions, where a firm’s current emissions are influenced by its past emissions due to financial policies and operational continuity, we use lagged values of the dependent variable as valid instruments.

To examine our GMM model, we conduct multiple diagnostic tests. First, we assess instrument validity using the Hansen J-test, which tests the null hypothesis that the instruments are exogenous.

Table 12 reports an insignificant

p-value (

> 0.10), indicating that the instruments used in the model are valid and do not suffer from overidentification issues. Second, we test for serial correlation in the error terms using the Arellano-Bond (AR) test for first-order (AR(1)) and second-order (AR(2)) autocorrelation. The AR(1) test yields a significant

p-value (

< 0.05), which is expected due to the inclusion of the lagged dependent variable. However, the AR(2) test is insignificant, confirming the absence of second-order autocorrelation and ensuring the proper specification of the model. As shown in

Table 12, our findings remain consistent with baseline results, demonstrating that SA adoption is positively and significantly associated with carbon emissions, reinforcing the reliability of our empirical evidence while ensuring that our results are robust against dynamic endogeneity and reverse causality biases.

4.4.4. Dynamic Analysis

We conducted a dynamic analysis using lagged and lead regression models to examine the temporal relationship between SA and carbon transparency.

Table 13 gives the results for temporal dynamics and potential reverse causality. The lagged specification shows that prior-period SA (L.SA) is positively and significantly associated with subsequent carbon transparency (CARBON, SCOPE1, and SCOPE2), reducing concerns regarding simultaneity and suggesting that the relationship of assurance persists over time. Moreover, the future-effect model provides particularly compelling evidence for causality. The current SA predicts carbon transparency one year ahead (CARBON

t+1, SCOPE1

t+1, and SCOPE2

t+1), with coefficient magnitudes comparable to the contemporaneous effect. These findings highlight SA practices and forward-looking influence in driving carbon transparency, reinforcing its role as a governance mechanism for long-term carbon accountability and sustainability.

5. Conclusions

This study examines the relationship between sustainability assurance (SA) and carbon disclosure transparency using a sample of publicly listed firms from ASEAN-5 countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand) over the period 2018–2022. Using panel regression, the findings suggest that firms adopting SA tend to report higher carbon emissions, reinforcing the hypothesis that SA is associated with more transparent carbon disclosures.

These results support Agency Theory, which posits that SA functions as an external monitoring mechanism that reduces information asymmetry by enhancing the credibility and reliability of carbon data. The findings are also in line with Stakeholder Theory, which suggests that firms improve their disclosure practices to meet stakeholder expectations, even if such disclosures expose substantial emissions. Additional analyses show that the positive relationship between SA and carbon emissions reporting is more pronounced among firms with high environmental performance and higher property, plant, and equipment (PPE) efficiency, further reinforcing the idea that SA adoption reflects a firm’s strategic commitment to transparency rather than greenwashing. Moreover, the study finds that assured firms are more likely to disclose Scope 3 emissions, suggesting that SA plays a critical role in expanding carbon transparency beyond direct operational boundaries. However, we document that this effectiveness is context-dependent; the relationship is most significant under mandatory reporting regimes and in non-sensitive industries, whereas firms in environmentally sensitive sectors remain cautious about disclosing direct (Scope 1) emissions, likely due to proprietary costs, although they continue to transparently assure Scope 2 data.

Theoretically, this study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, it provides empirical evidence on the role of voluntary SA in enhancing the transparency of carbon disclosures in an emerging market context. By focusing on ASEAN—where natural resource dependency is high and carbon disclosure remains limited—this study underscores the strategic value of SA as both a credibility-enhancing and risk-management mechanism within voluntary sustainability frameworks. Second, we offer empirical evidence that addresses ongoing concerns regarding whether higher reported emissions can be interpreted as a sign of greater transparency. In particular, we find that firms with strong environmental performance and higher efficiency in the use of property, plant, and equipment (PPE) adopt SA as part of their efforts to ensure the credibility and transparency of their carbon disclosure. This finding validates the use of disclosure magnitude as a proxy for honesty rather than poor performance, extending the application of Agency Theory to the verification of non-financial reporting.

Practically, these findings offer concrete guidance for stakeholders. For corporate managers, particularly those in high-risk sectors or global supply chains, adopting SA serves as a strategic asset to legitimize their carbon profile and differentiate themselves from peers. For policymakers in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand, the finding that SA is most effective under mandatory regimes suggests that relying solely on market forces is insufficient. Regulators should accelerate the transition to mandatory assurance. However, given that our results show significant benefits from limited assurance—which dominates the ASEAN landscape—policymakers should initially promote limited assurance as a feasible entry point before progressing to reasonable assurance. This phased approach aligns with market readiness while ensuring immediate transparency improvements before the full adoption of IFRS S1 and S2 standards.

This study is subject to several limitations that offer avenues for future research. First, our measure of transparency relies on self-reported carbon data from Refinitiv. While assurance mitigates credibility concerns, the underlying data may still suffer from measurement errors or self-selection bias inherent in voluntary disclosures. Second, our measurement of SA only captures whether a firm’s non-financial report is assured, without considering specific assurance attributes such as assurance level, scope, or provider type. As a result, the findings may not fully capture the complexities and nuances of how SA enhances carbon disclosure transparency. Third, the findings are specific to the ASEAN-5 context, where resource extraction is dominant. Thus, the results may not be generalizable to service-oriented economies or developed Western markets with mature assurance ecosystems. Fourth, although we employ several robustness checks, including PSM, 2SLS, and System GMM, to mitigate endogeneity concerns, our statistical approach still faces the typical limitations of observational data. In particular, potential omitted variables (e.g., managerial environmental orientation and country-specific enforcement intensity) that are unobservable and difficult to quantify may influence both the adoption of SA and firms’ carbon emission outcomes. Finally, our observation period (2018–2022) captures the pre-IFRS S1/S2 era. Future research should examine how the global adoption of these new standards after 2023 influences the shift from limited to reasonable assurance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S.; methodology, N.S. and A.H.M.N.; software, N.S. and Z.A.N.; validation, N.S. and S.H.; formal analysis, N.S. and Z.A.N.; investigation, N.S. and Z.A.N.; resources, S.H. and A.H.M.N.; data curation, Z.A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S., Z.A.N. and S.H.; writing—review and editing, N.S., A.H.M.N. and A.A.; visualization, N.S. and Z.A.N.; supervision, N.S. and A.A.; project administration, N.S. and A.A.; funding acquisition, N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universitas Airlangga, grant number 368/UN3.LPPM/PT.01.03/2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author when it is a reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hamidah Dwi Nita for her valuable assistance and insightful statistical advice, which helped to improve the research design and analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdalla, A. A. A., Alodat, A. Y., Salleh, Z., & Al-Ahdal, W. M. (2025). The effect of audit committee effectiveness, internal audit size and outsourcing on greenhouse gas emissions disclosure. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 22(4), 1072–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A. A. A., Salleh, Z., Hashim, H. A., Wan Zakaria, W. Z., & Al-ahdal, W. M. (2024). The effect of board of directors attributes, environmental committee and institutional ownership on carbon disclosure quality. Business Strategy & Development, 7(4), e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A. A., Salleh, Z., Alahdal, W. M., Hussien, A. M., Bajaher, M., & Baatwah, S. R. (2025). The effect of the board of directors, audit committee, and institutional ownership on carbon disclosure quality: The moderating effect of environmental committee. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 32(2), 2254–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alola, A. A., Bekun, F. V., & Sarkodie, S. A. (2019). Dynamic impact of trade policy, economic growth, fertility rate, renewable and non-renewable energy consumption on ecological footprint in Europe. Science of the Total Environment, 685, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alta’any, M., Meqbel, R., Oyewo, B., & Alsulami, A. (2025). Towards enhanced sustainability reporting credibility: The role of national governance in Europe. Business Strategy & Development, 8(3), e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiagyei, K., Djajadikerta, H. G., & Mat Roni, S. (2023). The impact of corporate governance on integrated reporting (IR) quality and sustainability performance: Evidence from listed companies in South Africa. Meditari Accountancy Research, 31(4), 1068–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, H. M., Khan, I., Latif, M. I., Komal, B., & Chen, S. (2022). Understanding the dynamics of natural resources rents, environmental sustainability, and sustainable economic growth: New insights from China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(39), 58746–58761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante-Appiah, B., & Lambert, T. A. (2023). The role of the external auditor in managing environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reputation risk. Review of Accounting Studies, 28(4), 2589–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, C., Caro, F., & Corbett, C. J. (2016). The state of supply chain carbon footprinting: Analysis of CDP disclosures by US firms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 135, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O., & Heras-Saizarbitoria, I. (2020). Sustainability reporting assurance: Creating stakeholder accountability through hyperreality? Journal of Cleaner Production, 243, 118596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braam, G. J. M., De Weerd, L. U., Hauck, M., & Huijbregts, M. A. J. (2016). Determinants of corporate environmental reporting: The importance of environmental performance and assurance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 129, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P. M., Li, Y., Richardson, G. D., & Vasvari, F. P. (2008). Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4–5), 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darus, F., Sawani, Y., Mohamed Zain, M., & Janggu, T. (2014). Impediments to CSR assurance in an emerging economy. Managerial Auditing Journal, 29(3), 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datt, R., Prasad, P., Vitale, C., & Prasad, K. (2022). International evidence of changing assurance practices for carbon emissions disclosures. Meditari Accountancy Research, 30(6), 1594–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H., Liu, W., Liu, Y., & Xiong, Z. (2022). Fixed asset changes with carbon regulation: The cases of China. Journal of Environmental Management, 306, 114494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J., Yang, X., Long, D., & Xin, Y. (2024). Modelling the influence of natural resources and social globalization on load capacity factor: New insights from the ASEAN countries. Resources Policy, 91, 104816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L. W., Pan, S. J., Liu, G. Q., & Zhou, P. (2017). Does energy efficiency affect financial performance? Evidence from Chinese energy-intensive firms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 151, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M. B., Azantouti, A. S. A., & Zaman, R. (2024). Non-financial information assurance: A review of the literature and directions for future research. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 15(1), 48–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M. B., & De Villiers, C. (2019). How sustainability assurance engagement scopes are determined, and its impact on capture and credibility enhancement. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 33(2), 417–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Feijoo, B., Romero, S., & Ruiz, S. (2016). The assurance market of sustainability reports: What do accounting firms do? Journal of Cleaner Production, 139, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, F. M., Elliott, B., & Ibanez, D. (2023, November 28). Southeast Asian cities have some of the most polluted air in the world. El niño is making it worse. Available online: https://www.wri.org/insights/air-pollution-southeast-asia-cities-jakarta-el-nino (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Fransisca, F., Pratama, A., & Muhammad, K. (2025). Does sustainability pay off? Examining governance, performance, and debt costs in Southeast Asian companies (A survey of public companies in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand for the 2021–2023 period). Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(7), 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman. [Google Scholar]

- Gaio, C., Gonçalves, T., & Sousa, M. V. (2022). Does corporate social responsibility mitigate earnings management? Management Decision, 60(11), 2972–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, M. B., & Nishitani, K. (2020). Views of corporate managers on assurance of sustainability reporting: Evidence from Japan. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 17(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, F. (2017). The effects of board characteristics and sustainable compensation policy on carbon performance of UK firms. The British Accounting Review, 49(3), 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrer, T., & Lehner, O. M. (2024). Assuring the unknowable: A reflection on the evolving landscape of sustainability assurance for financial auditors. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 67, 101413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A., Elamer, A. A., Fletcher, M., & Sobhan, N. (2020). Voluntary assurance of sustainability reporting: Evidence from an emerging economy. Accounting Research Journal, 33(2), 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertwich, E., & Wood, R. (2018). The growing importance of Scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions from industry. Environmental Research Letters, 13(10), 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. (2023). How much CO2 do countries in Asia Pacific emit? International Energy Agency. Available online: https://www.iea.org/regions/asia-pacific/emissions#how-much-co2-do-countries-in-asia-pacific-emit (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Issa, A. (2025a). Driving emissions reduction: The power of external sustainability assurance and internal governance committees. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 22(1), 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, A. (2025b). Sustainability committees’ influence on ESG controversies and sustainability assurance: A comparative study in polluting and non-polluting firms. Journal of Global Responsibility, 16(4), 686–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S., Gan, C., & Li, Z. (2025). Climate governance and carbon transparency: Evidence from nonfinancial firms. Management Decision. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanashiro, P. (2020). Can environmental governance lower toxic emissions? A panel study of US high-polluting industries. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(4), 1634–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, I. (2024). Boardroom diversity and carbon emissions: Evidence from the UK firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 195(4), 899–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A. (2014). The value of firms’ voluntary commitment to improve transparency: The case of special segments on Euronext. Journal of Corporate Finance, 25, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzey, C., Elbardan, H., Uyar, A., & Karaman, A. S. (2023). Do shareholders appreciate the audit committee and auditor moderation? Evidence from sustainability reporting. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 31(5), 808–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L., Tang, Q., Fan, H., & Ayers, J. (2023). Corporate carbon assurance and the quality of carbon disclosure. Accounting & Finance, 63(1), 657–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ferrero, J., García-Sánchez, I., & Ruiz-Barbadillo, E. (2018). The quality of sustainability assurance reports: The expertise and experience of assurance providers as determinants. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(8), 1181–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, C. C. J. M., Eldomiaty, T. I., Choi, C. J., & Hilton, B. (2005). Corporate governance and institutional transparency in emerging markets. Journal of Business Ethics, 59, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttakin, M. B., Rana, T., & Mihret, D. G. (2022). Democracy, national culture and greenhouse gas emissions: An international study. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(7), 2978–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathaniel, S. (2021). Environmental degradation in ASEAN: Assessing the criticality of natural resources abundance, economic growth and human capital. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(17), 21766–21778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathaniel, S., & Khan, S. A. R. (2020). The nexus between urbanization, renewable energy, trade, and ecological footprint in ASEAN countries. Journal of Cleaner Production, 272, 122709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, D. L., Dapko, J. L., Arnold, R. W., & Arnold, D. (2016). Exploring transparency: A new framework for responsible business management. Management Decision, 54(1), 222–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchell, J. (2018). Can the implications of the GHG Protocol’s scope 3 standard be realized? Journal of Cleaner Production, 185, 941–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajogo, D., Castka, P., Yiu, D., Yeung, A. C. L., & Lai, K. (2016). Environmental Audits and third-party certification of management practices: Firms’ motives, audit orientations, and satisfaction with certification. International Journal of Auditing, 20(2), 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. (2024). Sustainability counts III: Traversing the landscapes of sustainability reporting in Asia Pacific and beyond. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/esg/esg-asia-pacific/sustainability-counts.html (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Qian, C., Gao, X., & Tsang, A. (2015). Corporate philanthropy, ownership type, and financial transparency. Journal of Business Ethics, 130, 851–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W., Hörisch, J., & Schaltegger, S. (2018). Environmental management accounting and its effects on carbon management and disclosure quality. Journal of Cleaner Production, 174, 1608–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranängen, H., & Zobel, T. (2014). Revisiting the ‘how’ of corporate social responsibility in extractive industries and forestry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 84, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, M., Windsor, C., & Wahyuni, D. (2011). An investigation of voluntary corporate greenhouse gas emissions reporting in a market governance system: Australian evidence. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 24(8), 1037–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A., Ringel, E., & Pendleton, S. M. (2024). Transparency reports as CSR reports: Motives, stakeholders, and strategies. Social Responsibility Journal, 20(1), 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohani, A., Jabbour, M., & Aliyu, S. (2023). Corporate incentives for obtaining higher level of carbon assurance: Seeking legitimacy or improving performance? Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 24(4), 701–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, C. C., Zorio-Grima, A., & Merello, P. (2021). Economic development and CSR assurance: Important drivers for carbon reporting… yet inefficient drivers for carbon management? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 163, 120424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Barbadillo, E., & Martínez-Ferrero, J. (2022). The choice of incumbent financial auditors to provide sustainability assurance and audit services from a legitimacy perspective. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 13(2), 459–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Blanco, S., Romero, S., & Fernandez-Feijoo, B. (2022). Green, blue or black, but washing–What company characteristics determine greenwashing? Environment, Development and Sustainability, 24(3), 4024–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryou, J. W., Tsang, A., & Wang, K. T. (2022). Product market competition and voluntary corporate social responsibility disclosures. Contemporary Accounting Research, 39(2), 1215–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sancho, M., Martínez-Ferrero, J., & Perote-Peña, J. (2024). Managerial capture of sustainability assurance. Empirical evidence and capital market reactions. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 15(2), 520–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M., Qu, Y., Javed, S. A., Zafar, A. U., & Rehman, S. U. (2020). Relation of environment sustainability to CSR and green innovation: A case of Pakistani manufacturing industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 253, 119938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simnett, R. (2012). Assurance of sustainability reports: Revision of ISAE 3000 and associated research opportunities. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 3(1), 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C., Irfan, M., Razzaq, A., & Dagar, V. (2022). Natural resources and financial development: Role of business regulations in testing the resource-curse hypothesis in ASEAN countries. Resources Policy, 76, 102612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q., & Luo, L. (2014). Carbon management systems and carbon mitigation. Australian Accounting Review, 24(1), 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N. M., & Tran, M. H. (2023). Do audit firm reputation provide insight into financial reporting quality? Evidence from accrual and real management of listed companies in Vietnam. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. (2025a). Audit quality and materiality disclosure quality in integrated reporting: The moderating effect of carbon assurance quality. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 32(3), 3785–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. (2025b). Determinants of the selection of sustainability assurance providers and consequences for firm value: A review of empirical research. Meditari Accountancy Research, 33(7), 443–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J., Wong, N., Li, W. Y., & Chen, L. (2016). Sustainability assurance: An emerging market for the accounting profession. Pacific Accounting Review, 28(3), 238–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T., Kang, C., & Zhang, H. (2022). China’s efforts towards carbon neutrality: Does energy-saving and emission-reduction policy mitigate carbon emissions? Journal of Environmental Management, 316, 115286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X., Wu, C., Chen, C. C., & Zhou, Z. (2020). The influence of corporate social responsibility on incumbent employees: A meta-analytic investigation of the mediating and moderating mechanisms. Journal of Management, 48(1), 114–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z., Zhou, H., Peng, D., Chen, X., & Li, S. (2018). Carbon disclosure, financial transparency, and agency cost: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing listed companies. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 54(12), 2669–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |