Beyond Quotas: The Influence of Board Gender Diversity on Capital Structure in Firms from Latin America and the Caribbean

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Empirical Evidence and Research Gaps

2.3. Research Question and Hypothesis Development

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Data Sources

3.2. Sample Selection and Potential Biases

3.3. Variable Definitions and Measurement

3.3.1. Dependent Variable

3.3.2. Main Independent Variable

3.3.3. Control Variables

- Board size (BS): Total number of board members (log-transformed to address skewness).

- Independent board members (IBM): Percentage of independent directors on the board.

- CEO board member: Binary variable indicating whether the CEO serves on the board (CEO duality).

- Board structure type: Categorical variable distinguishing between unitary, two-tier, and mixed board structures.

- Total assets (TA): Log of total assets as a proxy for firm size.

- Profitability: Return on assets (ROA) to control for earnings capacity.

- Growth opportunities: Market-to-book ratio.

- Asset tangibility: Property, plant, and equipment divided by total assets.

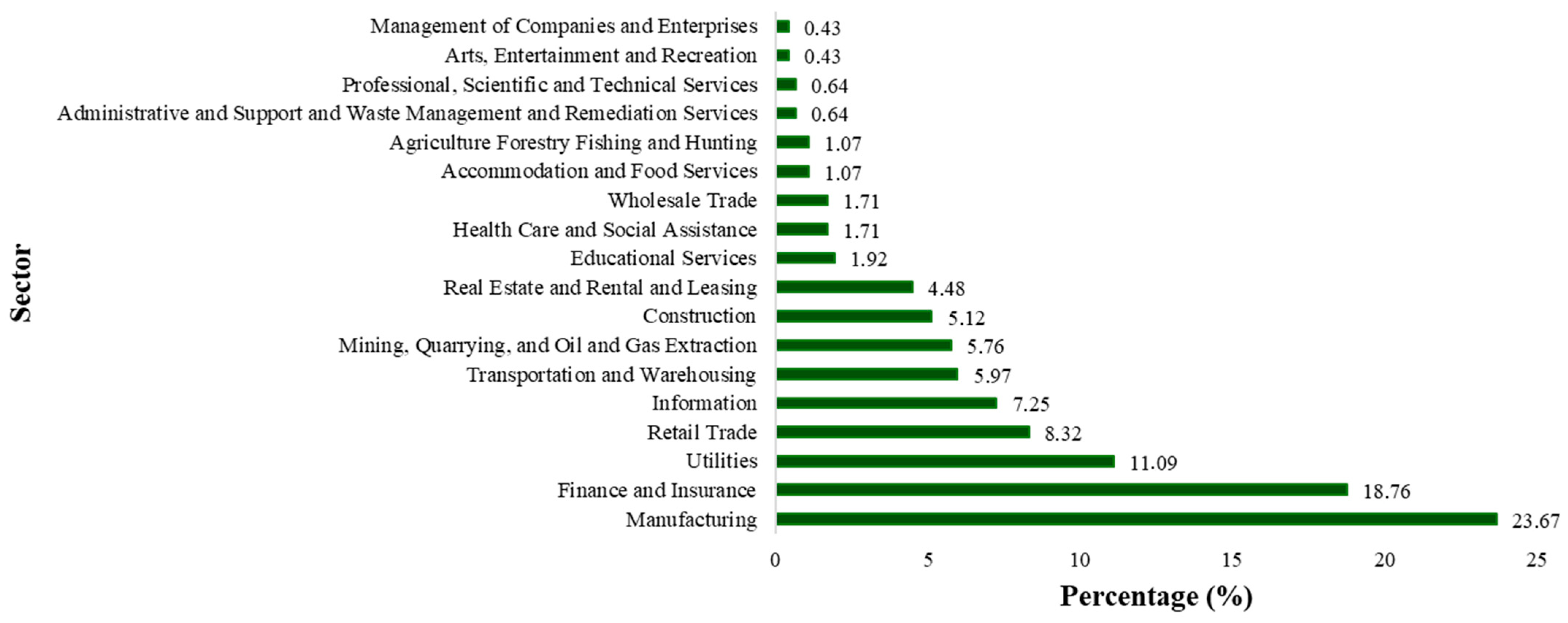

- Industry: NAICS sector classifications.

- GDP growth: Annual real GDP growth rate.

- Financial development: Private credit by banks as a percentage of GDP.

- Governance quality: World Bank governance indicators (when available).

- Legal origin: Binary variables for civil law vs. common law traditions.

3.4. Econometric Methodology

- αi: firm-fixed effects.

- λt: time-fixed effects.

- δs: industry-fixed effects.

- γc: country-fixed effects.

3.5. Estimation Technique and Robustness

3.6. Model Selection and Diagnostic Tests

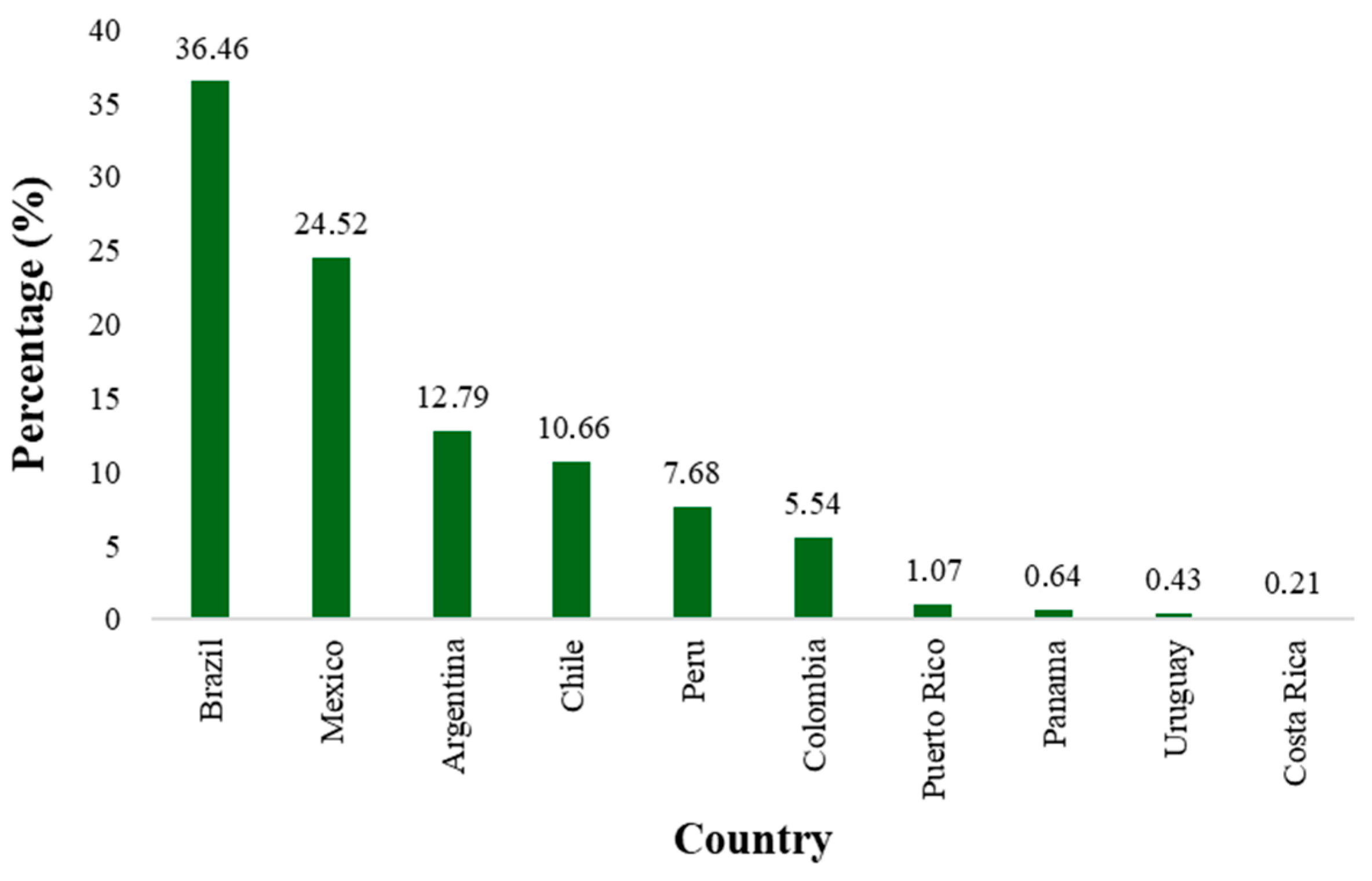

3.7. Sample Characteristics and Representativeness

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.2. Construction of the Model

4.2.1. Correlation Analysis

4.2.2. Multicollinearity Assessment and Model Selection

4.3. Model Results

4.3.1. Initial Models

4.3.2. Fixed Effects Models with Driscoll–Kraay Standard Errors (M1–M4)

4.3.3. Extended Models with Driscoll–Kraay Standard Errors (M5–M7)

4.3.4. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.3.5. Addressing Endogeneity

- F1_BGD (Lead of BGD): This variable represents the value of BoardGenderDiversity for a given firm in the next period (year *t + 1*). It is used in the Placebo Test to check if future board composition can explain current debt levels—a scenario that would strongly suggest reverse causality.

- L1_DebtWeight (Lag of Debt Weight): This variable represents the value of DebtWeight for a given firm in the previous period (year *t − 1*). It is a standard control in dynamic models and is used in the Granger tests to isolate the effect of past leverage on current diversity.

- L1_BGD (Lag of BGD): This variable represents the value of BoardGenderDiversity for a given firm in the previous period (year *t − 1*). It is used to test if past diversity helps predict current debt levels, controlling for past debt.

4.3.6. Summary of Key Findings

- Primary Result: BGD is negatively associated with firm leverage across multiple specifications, with economically meaningful effect sizes.

- Robustness: The relationship is robust to alternative measures of capital structure, different sample compositions, and various econometric specifications.

- Non-linearity: Evidence supports critical mass theory, with stronger effects at higher levels of female representation.

- Moderation: The relationship is stronger for larger firms, consistent with enhanced governance benefits in more complex organizations.

- Context Dependence: Significant variation across countries and industries suggests that institutional factors moderate the BGD–capital structure relationship.

5. Discussion

Interpretation of Main Findings

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dependent Variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| Debt Weight | ||

| Full Sample (2015–2022) | Pre COVID-Sample (2015–2019) | |

| BoardGenderDiversity | −0.037 (0.049) | −0.162 * (0.068) |

| BoardSizeL | 4.837 * (2.216) | −0.259 (2.756) |

| IndependentBoardMembers | 0.016 (0.026) | −0.028 (0.050) |

| TotalAssetsL | 7.366 *** (0.551) | 5.890 ** (2.257) |

| BoardStructureTypeTwo-tier | −3.395 ** (1.162) | −6.160 (3.743) |

| BoardStructureTypeUnitary | −0.870 (1.415) | −3.917 (3.048) |

| CEOBoardMember | −1.387 *** (0.393) | −1.284 (1.982) |

| Observations | 1893 | 1131 |

| R2 | 0.065 | 0.052 |

| Adjusted R2 | −0.124 | −0.306 |

| F Statistic | 15.661 *** (df = 7; 1573) | 6.461 *** (df = 7; 820) |

References

- 30% Club. (2023, March 9). Growth through diversity, increasing gender balance. Global Mission. Available online: https://30percentclub.org/ (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Adams, R. B., & Ferreira, D. (2009). Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 94(2), 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusei, M., & Obeng, E. Y. T. (2019). Board gender diversity and the capital structure of microfinance institutions: A global analysis. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 71, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnese, P., Battaglia, F., Busato, F., & Taddeo, S. (2023). ESG controversies and governance: Evidence from the banking industry. Finance Research Letters, 53, 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhossini, M. A., Ntim, C. G., & Zalata, A. M. (2021). Corporate board committees and corporate outcomes: An international systematic literature review and agenda for future research. The International Journal of Accounting, 56(01), 2150001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Lawati, H., & Alshabibi, B. (2023). Does board structure drive Sustainable Development Goals disclosure? Evidence from an emerging market. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 12(2), 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P., Couto, E. B., & Francisco, P. M. (2015). Board of directors’ composition and capital structure. In Research in international business and finance (Vol. 35, pp. 1–32). Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A., ur Rehman, R., Ali, R., & Mohd Said, R. (2022). Corporate governance and capital structure: Moderating effect of gender diversity. SAGE Open, 12(1), 21582440221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammer, M. A., Aliedan, M. M., & Alyahya, M. A. (2020). Do corporate environmental sustainability practices influence firm value? The role of independent directors: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 12(22), 9768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango-Home, M. C., González-Ruiz, J. D., & Valencia-Arias, A. (2023). Relationship between women on board directors and economic value added: Evidence from Latin American companies. Sustainability, 15(17), 13179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banco Central do Brasil. (2023). Historical series of the selic rate. Available online: https://www.bcb.gov.br/en/statistical/timeseries (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Bazhair, A. H. (2023). Board governance mechanisms and capital structure of saudi non-financial listed firms: A dynamic panel analysis. SAGE Open, 13(2), 215824402311729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Saad, S., & Belkacem, L. (2022). Does board gender diversity affect capital structure decisions? Corporate Governance (Bingley), 22(5), 922–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubaker, S., Dang, R., & Nguyen, D. K. (2014). Does board gender diversity improve the performance of French-listed firms? Management & Prospective, 31(1), 259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Carstens, A. (2021, April 5). The future of money and the monetary system. Speech at the International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, D. A., D’Souza, F., Simkins, B. J., & Simpson, W. G. (2010). The gender and ethnic diversity of US boards and board committees and firm financial performance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 18(5), 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y., Ali, M. M., Wang, Q., & Lin, S.-H. (2023). Corporate board gender diversity and financing decision. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 15(8), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S., Doan, T., & Toscano, F. (2021). Top executive gender, board gender diversity, and financing decisions: Evidence from debt structure choice. Journal of Banking & Finance, 125, 106070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didier, T., Huneeus, F., Larrain, M., & Schmukler, S. L. (2021). Financing firms in hibernation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Financial Stability, 53, 100837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, J., & Kraay, A. C. (1998). Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent data. Review of Economics and Statistics, 80, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzahar, H., Zalata, A., & Hassaan, M. (2022). Attributes of female directors and accruals-based earnings management. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2139212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeani, E., Kwabi, F., Salem, R., Usman, M., Alqatamin, R. M. H., & Kostov, P. (2022). Corporate board and dynamics of capital structure: Evidence from UK, France and Germany. International Journal of Finance and Economics, 28(3), 3281–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M. U., Su, K., Boubaker, S., & Gull, A. A. (2022). Does gender promote ethical and risk-averse behavior among CEOs? An illustration through related-party transactions. Finance Research Letters, 47, 102730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C. J., & Herrero, B. (2021). Female directors, capital structure, and financial distress. Journal of Business Research, 136, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavana, G., Gottardo, P., & Moisello, A. M. (2023). Board diversity and corporate social performance in family firms. The moderating effect of the institutional and business environment. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(5), 2194–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ruiz, J. D., Marín-Rodríguez, N. J., & Peña, A. (2024). Board gender diversity and cost of debt financing: Evidence from Latin American and the Caribbean firms. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 35(2), 224–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K., Karaman, A. S., Uyar, A., & Kilic, M. (2023). Board structure and financial performance in the logistics sector: Do contingencies matter? Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 176, 103187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H., & Gu, X. (2021). Linkage between inclusive digital finance and high-tech enterprise innovation performance: Role of debt and equity financing. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 814408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, M., & Raviv, A. (1991). The theory of capital structure. The Journal of Finance, 46(1), 297–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A. J., & Dalziel, T. (2003). Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A. J., Withers, M. C., & Collins, B. J. (2009). Resource dependence theory: A review. Journal of Management, 35(6), 1404–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordofa, D. F. (2023). The impact of board gender diversity on capital structure: Evidence from the Ethiopian banking sector. Cogent Business and Management, 10(3), 2253995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2021). Policy responses to COVID-19. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19 (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2022). Regional economic outlook: Western hemisphere—Navigating a tightening cycle. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Jackling, B., & Johl, S. (2009). Board structure and firm performance: Evidence from India’s top companies. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(4), 492–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, R., Ali, H., & Mohamed, E. K. A. (2021). The sustainable development goals and corporate sustainability performance: Mapping, extent and determinants. Journal of Cleaner Production, 311, 127599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn Ferry. (2022). Women on boards in Latin America 2022. Available online: https://www.kornferry.com/insights/articles/women-on-boards-in-latin-america-2022 (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- La Rocca, M., Neha, N., & La Rocca, T. (2020). Female management, overconfidence and debt maturity: European evidence. Journal of Management and Governance, 24(3), 713–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, F., Liberatore, G., Mazzi, F., & Terzani, S. (2018). The impact of corporate social performance on the cost of debt and access to debt financing for listed European non-financial firms. European Management Journal, 36(4), 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Delgado, P., & Diéguez-Soto, J. (2020). Indebtedness in family-managed firms: The moderating role of female directors on the board. Review of Managerial Science, 14(4), 727–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, M. U., Djuwarsa, T., & Setiawan, S. (2023). Board characteristics and dividend payout decisions: Evidence from Indonesian conventional and Islamic bank. Managerial Finance, 49(11), 1762–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Cardenas, V., Gonzalez-Ruiz, J. D., & Duque-Grisales, E. (2022). Board gender diversity and firm performance: Evidence from Latin America. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 12(3), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliken, F. J., & Martins, L. L. (1996). Searching for common threads: Understanding the multiple effects of diversity in organizational groups. Academy of Management Review, 21(2), 402–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J., & Vogel, D. (2009). Corporate social responsibility, government, and civil society. In A. Crane, D. Matten, A. McWilliams, J. Moon, & D. S. Siegel (Eds.), The oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility. Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooneeapen, O., Abhayawansa, S., & Mamode Khan, N. (2022). The influence of the country governance environment on corporate environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 13(4), 953–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, M. A., Lin, J., ur Rehman, R., Ahmad, M. I., & Ali, R. (2020). Does capital structure mediate the link between CEO characteristics and firm performance? Management Decision, 58(1), 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, G. J., & Kiel, G. C. (2007). Can directors impact performance? A case-based test of three theories of corporate governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15(4), 585–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisiyama, E. K., & Nakamura, W. T. (2018). Diversidade do conselho de administração e a estrutura de capital. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 58(6), 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (1978). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1496213 (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Poletti-Hughes, J., & Martínez Garcia, B. (2022). Leverage in family firms: The moderating role of female directors and board quality. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 27(1), 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, R. D., & Hermawan, A. A. (2023). Do country-level and firm-level governance quality influence bank sustainability performance? In Research in finance (Vol. 37, pp. 15–37). Emerald Publishing. (In Finance). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, M. C., Bel-Oms, I., & Gallego-Álvarez, I. (2022). Corporate social responsibility reporting and capital structure: Does board gender diversity mind in such association? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30, 1588–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, A., Alifiah, M. N., & Dikko, U. M. (2020). The dynamic relationship between board composition and capital structure of the nigerian listed firms. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(11), 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargon, B. (2024). Board structure and net working capital: Evidence from FTSE all share index companies. Applied Economics, 56(60), 9270–9283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M. H. (2021). Environmental, social and governance performance and financial risk: Moderating role of ESG controversies and board gender diversity. Resources Policy, 72, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siregar, M. E. S., Suherman, S., Mahfirah, T. F., Usman, B., Zairin, G. M., & Kurniawati, H. (2023). The role of female executives in capital structure decisions: Evidence from a Southeast Asian country. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 24(4), 939–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoiljković, A., Tomić, S., Leković, B., Uzelac, O., & Ćurčić, N. V. (2024). The impact of capital structure on the performance of Serbian manufacturing companies: Application of agency cost theory. Sustainability, 16(2), 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodosio, J., Lisboa, I., & Oliveira, C. (2023). Board gender diversity and capital structure: Evidence from the Portuguese listed firms. International Journal of Applied Economics, Finance and Accounting, 16(2), 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2023). Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. United Nations.

- Wang, P., & Ramzan, M. (2020). Do corporate governance structure and capital structure matter for the performance of the firms? An empirical testing with the contemplation of outliers. PLoS ONE, 15(2), e0229157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2023). World development indicators. The World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Yakubu, I. N., & Oumarou, S. (2023). Boardroom dynamics: The power of board composition and gender diversity in shaping capital structure. Cogent Business and Management, 10(2), 2236836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, M., Wang, M., Abuhijleh, S. T. F., Issa, A., Saleh, M. W. A., & Ali, F. (2020). Corporate governance practices and capital structure decisions: The moderating effect of gender diversity. Corporate Governance (Bingley), 20(5), 939–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamil, I. A., Ramakrishnan, S., Jamal, N. M., Hatif, M. A., & Khatib, S. F. A. (2023). Drivers of corporate voluntary disclosure: A systematic review. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 21(2), 232–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | 25% | 50% | 75% | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGD | 10.845 | 11.009 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 16.667 | 85.714 |

| BS | 9.865 | 3.469 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 25 |

| IBM | 38.813 | 23.426 | 0 | 22.222 | 37.5 | 55.556 | 100 |

| DW | 38.024 | 24.92 | 0 | 17.261 | 37.023 | 55.819 | 99.331 |

| TA | 15,764.142 | 45,409.163 | 1.467 | 1525.672 | 4166.659 | 12,359.188 | 524,123.575 |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | BGD | BS | IBM | TA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGD | 10.85 | 11.01 | 1 | |||

| BS | 9.87 | 3.47 | −0.04 * | 1 | ||

| [−0.09, −0.00] | ||||||

| IBM | 38.81 | 23.43 | 0.19 ** | −0.01 | 1 | |

| [0.14, 0.23] | [−0.05, 0.03] | |||||

| TA | 15,764.14 | 45,409.16 | 0.06 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.04 | 1 |

| [0.02, 0.10] | [0.05, 0.13] | [−0.00, 0.08] | ||||

| DW | 38.02 | 24.92 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.06 ** | 0.25 ** |

| [−0.06, 0.03] | [−0.05, 0.03] | [0.02, 0.10] | [0.21, 0.29] |

| Board Gender Diversity | Board Size | Independent Board Members | Total Assets |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.041 | 1.011 | 1.036 | 1.013 |

| Best Model Selection |

|---|

| H0: multiple regression vs. H1: fixed-effects regression F-test for individual effects |

| p-value < 0.00000000000000022 |

| H0: random-effect regression vs. H1: fixed-effects regression Hausman test |

| p-value = 0.000689 |

| Variable | OLS Model | Fixed Model | Random Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| BGD | −0.096 * (−0.174, −0.018) | 0.173 *** (0.110, 0.235) | 0.144 *** (0.084, 0.204) |

| TA | 0.0001 *** (0.0001, 0.0002) | 0.0002 *** (0.0002, 0.0003) | 0.0002 *** (0.0001, 0.0002) |

| BS | −0.260 (−0.505, −0.015) | 0.155 (−0.109, 0.420) | 0.073 (−0.172, 0.319) |

| IBM | 0.061 ** (0.024, 0.098) | 0.086 *** (0.045, 0.127) | 0.075 ** (0.037, 0.113) |

| Constant | 37.093 *** (34.095, 40.092) | 30.204 *** (26.592, 33.816) | |

| Observations | 2202 | 2202 | 2202 |

| R2 | 0.067 | 0.036 | 0.038 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.065 | −0.133 | 0.036 |

| F Statistic | 39.235 *** (df = 4; 2197) | 17.381 *** (df = 4; 1873) | 81.364 *** |

| Model | Adds | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| M1 | Time FE only | Base model to compare others |

| M2 | Log-transformed variables | Handles scale and skewness issues |

| M3 | TotalAssetsL | Adds size control, improves specification |

| M4 | BoardStructureType, CEOBoardMember | Adds board characteristics and leadership controls |

| M5–M6 | Industry/Country FE | Controls for time-varying group-specific heterogeneity |

| M7 | Firm + Time FE (two-way FE) | Controls for all time-invariant firm characteristics (strongest control) |

| Dependent Variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debt Weight | ||||

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | |

| BoardGenderDiversity | −0.239 *** (0.053) | −0.109 ** (0.034) | −0.155 *** (0.032) | −0.234 *** (0.051) |

| BoardSize | 0.148 (0.205) | |||

| BoardSizeL | 0.422 (1.593) | −4.969 * (2.055) | −2.328 (1.967) | |

| IndependentBoardMembers | 0.013 (0.029) | 0.058 (0.031) | −0.025 (0.023) | −0.034 (0.027) |

| TotalAssets | 0.0001 *** (0.00000) | |||

| BoardStructureTypeTwo-tier | −5.899 ** (1.892) | −4.938 ** (1.827) | ||

| BoardStructureTypeUnitary | −2.306 (1.357) | −1.507 (1.062) | ||

| CEOBoardMember | −5.090 *** (1.385) | −4.401 ** (1.431) | ||

| TotalAssetsL | 5.494 *** (0.268) | 5.204 *** (0.328) | ||

| Observations | 1893 | 2202 | 2202 | 1893 |

| R2 | 0.083 | 0.004 | 0.132 | 0.123 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.076 | −0.0002 | 0.128 | 0.116 |

| F Statistic | 24.301 *** (df = 7; 1878) | 3.215 * (df = 3; 2191) | 83.405 *** (df = 4; 2190) | 37.590 *** (df = 7; 1878) |

| Dependent Variable: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Debt Weight | |||

| M5 | M6 | M7 | |

| BoardGenderDiversity | −0.254 *** (0.063) | −0.168 ** (0.063) | −0.037 (0.049) |

| BoardSizeL | 5.369 ** (1.716) | −1.359 (1.716) | 4.837 * (2.216) |

| IndependentBoardMembers | 0.050 ** (0.016) | −0.035 * (0.016) | 0.016 (0.026) |

| TotalAssetsL | 3.839 *** (0.467) | 6.450 *** (0.467) | 7.366 *** (0.551) |

| BoardStructureTypeTwo-tier | −5.101 *** (1.058) | −3.730 *** (1.058) | −3.395 ** (1.162) |

| BoardStructureTypeUnitary | 0.953 (0.781) | −0.943 (0.781) | −0.870 (1.415) |

| CEOBoardMember | −0.256 (1.330) | −5.016 *** (1.330) | −1.387 *** (0.393) |

| CountryofHeadquartersBrazil | 7.687 | ||

| CountryofHeadquartersChile | 15.807 | ||

| CountryofHeadquartersColombia | 18.134 ** | ||

| CountryofHeadquartersCosta Rica | −10.765 | ||

| CountryofHeadquartersMexico | −2.472 | ||

| CountryofHeadquartersPanama | 17.072 *** | ||

| CountryofHeadquartersPeru | 1.651 | ||

| CountryofHeadquartersPuerto Rico | −18.188 ** | ||

| CountryofHeadquartersUruguay | −13.698 *** | ||

| NAICSSectorNameAdministrative and Support and Waste Management and Remediation Services | −6.855 (4.725) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameAgriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting | −1.187 (10.004) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameConstruction | 10.142 (5.620) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameEducational Services | −9.460 (6.376) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameFinance and Insurance | −15.116 *** (2.524) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameHealth Care and Social Assistance | −24.991 *** (4.772) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameInformation | −10.301 ** (3.414) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameManagement of Companies and Enterprises | 12.156 (6.527) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameManufacturing | −10.355 ** (3.536) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameMining, Quarrying, and Oil and Gas Extraction | −13.150 ** (4.543) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameProfessional, Scientific, and Technical Services | −4.496 (3.823) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameReal Estate and Rental and Leasing | −6.574 * (3.102) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameRetail Trade | −17.310 *** (2.420) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameTransportation and Warehousing | −9.790 *** (2.482) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameUtilities | −9.759 * (3.900) | ||

| NAICSSectorNameWholesale Trade | −9.803 *** (1.778) | ||

| Observations | 1893 | 1893 | 1893 |

| R2 | 0.184 | 0.180 | 0.065 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.174 | 0.167 | −0.124 |

| F Statistic | 26.321 *** (df = 16; 1869) | 17.810 *** (df = 23; 1862) | 15.661 *** (df = 7; 1573) |

| Dependent Variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Debt Weight | Board Gender Diversity | ||

| Placebo | Granger 1 | Granger 2 | |

| F1_BGD | 0.001 (0.044) | ||

| L1_DebtWeight | 0.448 *** (0.024) | 0.008 (0.015) | |

| L1_BGD | −0.008 (0.042) | 0.465 *** (0.026) | |

| BoardSizeL | 3.226 * (1.722) | 5.492 *** (1.626) | 1.639 * (0.989) |

| IndependentBoardMembers | 0.035 (0.028) | 0.048 * (0.026) | 0.027 * (0.016) |

| TotalAssetsL | 6.803 *** (0.894) | 5.417 *** (0.924) | 0.709 (0.562) |

| BoardStructureTypeTwo-tier | −4.123 ** (1.805) | −0.777 (1.667) | 0.318 (1.014) |

| BoardStructureTypeUnitary | −2.048 (1.676) | 0.843 (1.543) | 0.352 (0.938) |

| CEOBoardMember | −1.789 * (1.080) | −1.678 * (0.971) | −1.258 ** (0.591) |

| Observations | 1641 | 1607 | 1607 |

| R2 | 0.057 | 0.259 | 0.215 |

| Adjusted R2 | −0.165 | 0.076 | 0.022 |

| F Statistic | 11.465 *** (df = 7; 1327) | 56.223 *** (df = 8; 1289) | 44.087 *** (df = 8; 1289) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Ruiz, J.D.; Marín-Rodríguez, N.J.; Ospina-Patiño, C. Beyond Quotas: The Influence of Board Gender Diversity on Capital Structure in Firms from Latin America and the Caribbean. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090505

González-Ruiz JD, Marín-Rodríguez NJ, Ospina-Patiño C. Beyond Quotas: The Influence of Board Gender Diversity on Capital Structure in Firms from Latin America and the Caribbean. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(9):505. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090505

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Ruiz, Juan David, Nini Johana Marín-Rodríguez, and Camila Ospina-Patiño. 2025. "Beyond Quotas: The Influence of Board Gender Diversity on Capital Structure in Firms from Latin America and the Caribbean" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 9: 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090505

APA StyleGonzález-Ruiz, J. D., Marín-Rodríguez, N. J., & Ospina-Patiño, C. (2025). Beyond Quotas: The Influence of Board Gender Diversity on Capital Structure in Firms from Latin America and the Caribbean. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(9), 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090505