1. Introduction

In the modern fiat system, currency values are ultimately determined by supply and demand market factors. If a country experiences economic or political turmoil, the overall demand for its currency will likely fall. Holding all else constant, this can attract more consumption and investment as conditions improve, since the goods and services are cheaper in this country. It is well documented both theoretically and empirically that a weak, undervalued currency can have expansionary pressures that will ultimately lead to economic growth (i.e.,

Rodrik, 2008;

Gluzmann et al., 2012;

Mbaye, 2013). However, while aggregate-level growth is demonstrated through growth in GDP per capita, the distributions of gains equally through society are uncertain.

Stiglitz (

2007) and

Samuelson (

1962) recognize the uneven gains that can come from free trade and globalization, but do not specifically address how gains generated from an undervalued currency are distributed.

Kuznets (

1955) asserts that income inequality increases as a country industrializes but then peaks and declines with further development. This creates an inverted U-shaped curve of income distribution, which is referred to as the Kuznets Curve. While current inequalities in advanced market countries challenge this theory, emerging countries with growing tradable sectors may be experiencing the downward slope of the U-shaped inequality curve. For example,

Dollar (

2001) found that emerging and developing countries like India, Vietnam, and Uganda have recently increased efforts to open up their economies, which has resulted in faster growth and more poverty reduction. Therefore, this study seeks to determine if the economic growth induced through an undervalued currency will result in GDP per capita growth that also decreases the country’s income inequality. We will explore how this relationship exists for all countries in the study, as well as in relation to specific country groupings. To examine how currency misalignment affects income inequality across different types of countries, two types of groupings are used—one based on development level (Advanced, e.g., United States, United Kingdom, Switzerland vs. Emerging and Developing, e.g., Vietnam, Uruguay, and Ukraine, according to IMF classification) and the other based on income levels (High, e.g., Germany; Upper-Middle, e.g., Brazil; Lower-Middle, e.g., India; and Low-Income, according to World Bank rankings). The use of two groupings allows for us to test the robustness of the results across different classification criteria. These groupings are updated annually to ensure that the regressions reflect the correct classification for each country in each year. These classifications are shown in

Appendix A,

Table A1 and

Table A2.

In short, while past studies show that undervalued currencies can boost growth, it is less clear what this means for inequality. Policymakers often see undervaluation as a tool for economic growth, but if the gains are not shared equally, it can create new social and economic challenges. This makes it important to ask whether the benefits of currency misalignment are also distributed equally and help narrow the income gaps.

2. Literature Review

The valuation and purchasing power of currencies drive investor and consumer behavior, which can ultimately lead to economic expansion or contraction.

Keesing (

1979) found that the relative value of a country’s currency is a key variable in the competitiveness of its exports, which are an engine of economic growth. While the production function indicates that export competitiveness is largely based on capital, labor, and technology, consideration must also be given to the effects of currency valuations. In fact,

Yao (

2006) recognizes that in China, a more stable and undervalued renminbi has played a key role in the unprecedented economic growth that the country has experienced since the implementation of a fixed exchange rate policy in 1994. This has contributed to not only attracting a surge in foreign direct investment (FDI) but also creating more exports due to the increased consumption from developed nations.

The seminal research by

Rodrik (

2008) finds that an undervalued currency leads to growth in GDP per capita, even when accounting for changes in purchasing power parity. He accomplishes this through first indexing real exchange rates, which are the ratio of a country’s exchange rate to the purchasing power parity conversion factor. A currency value that falls below this purchasing power equilibrium is considered undervalued and is shown to significantly increase the growth rate of a developing country. This model of currency misalignment addresses the

Balassa (

1964) and

Samuelson (

1964) effect, which suggests that currencies should appreciate as productivity increases in relation to tradable goods. Therefore, as a country develops, its pricing structure should move toward more closely mirroring an advanced market country and reach an equilibrium.

Subramanian (

2010) argues that while this equilibrium currency value in the short term is a function of supply and demand, its long-term equilibrium value can be assessed through absolute purchasing power parity, relative purchasing power parity, or the real exchange rate.

McLeod and Mileva (

2011) and

Mbaye (

2013) further extend the literature on the factors that affect equilibrium value. They both show that undervalued currencies increase a country’s competitiveness and lead to growth in the tradable sector (sectors that have their goods and services traded internationally) by either overcoming market failures or through total factor productivity improvements.

While accounting for the Balassa–Samuelson effect is common in all methods, the construction of the real exchange rate varies.

McCown et al. (

2007) argues that exchange rate values can be inconsistent with equilibrium values not necessarily because they are “misaligned” but, instead, because these models often do not properly take into account the cyclical, temporary, or even random effects of global capital markets. Interestingly,

Tipoy et al. (

2018) showed

Rodrik’s (

2008) findings of undervalued currencies being the impetus to GDP growth to be robust. The relationship will hold even after accounting for different theories of constructing the real exchange rate.

Rodrik (

2008) recognizes that the undervalued currency improves global competitiveness, strengthens demand, and ultimately increases profits since the tradable sector is the common mechanism for growth in developing countries. As Rodrik states, “Simply put, undervaluation boots industrial activities.” He theorizes that the growth caused by undervalued currencies in tradable sectors is a correction of two distinct distortions. First, weak institutions within developing countries lead to poor contracting environments, making it difficult to invest in this sector. Secondly, poor information, lack of coordination, and other market imperfections can also hinder the tradable sector. However, undervalued currencies can provide an exogenous shock to the environment, which has the potential to overcome both of these impediments and to induce economic growth.

While

Rodrik (

2008) attributes the growth in the tradable sector to a correction of distortions,

Tipoy et al. (

2018) points to increases in the total factor productivity (TFP) of the sector as the source of this growth. TFP simply measures the level of output from a given input. As the demand for a country’s tradable goods increases, this leads to a transfer of resources from the non-tradable sector, thus positively increasing productivity.

Mbaye (

2013) suggests that the mechanisms for this are threefold—the ‘learning by doing effect’, ‘learning by doing externality effect’, and pure composition. The productivity improvements through accumulated experience spillover as workers transfer into other industries, as well as the generally higher productivity of the tradable sector—all of which contribute to higher levels of TFP.

Mbaye (

2013) believes these three effects likely occur simultaneously with an undervalued currency, leading to GDP growth. Additionally,

McLeod and Mileva (

2011) demonstrate the causal arrow relationship between undervaluation and TFP. Specifically, a 10% undervaluation increased the annual TFP rate by 0.2% in developing countries.

On the other hand, the relationship between economic growth and income inequality varies throughout the literature. On examining economic growth in relation to income inequality, GDP per capita (natural log) is often included as a control variable for economic growth on analyzing the determinant of income gap.

Odedokun and Round (

2001) found that the inverted U-shaped relationship did not hold in their sample. They attributed this to the fact that most of the countries analyzed were still in the early stages of development and, as a result, excluded the square of real per capita income from their equation. Similarly, many contemporary studies have also chosen to exclude the square of log GDP per capita when testing for income inequality, as it is either statistically insignificant or has the wrong sign. Similarly to these findings, we did not find support for Kuznets’s hypothesis of an inverted U-shaped curve in our analysis using the square of log GDP per capita. Therefore, we excluded the square term and used only the natural log of GDP per capita in our models.

Apart from the square of log GDP per capital, the effect of log GDP per capita on income inequality also yields mixed results. GDP per capita can be negatively correlated with inequality and poverty, which means that higher income contributes to reducing inequality and alleviating poverty (

Naceur & Zhang, 2016); mixed results were reported by

Ashenafi and Dong (

2023),

Dorn et al. (

2022), and others, when controlling for national income.

We hypothesized that the effect of economic growth is context dependent and might depend on different conditions such as stages of development and other factors, which will be examined further in this study as a controlling variable.

In addition to economic growth, other factors, such as inflation, trade openness, and financial development, are also frequently used as control variables for income inequality, though their effects also vary across different studies with the utilization of different samples, periods, and methods.

Blejer and Guerrero (

1990) found that inflation worsens income distribution, while

Odedokun and Round (

2001) and

Naceur and Zhang (

2016) mostly found no significant impact.

Berisha et al. (

2023) showed that the contemporaneous effect of inflation on inequality is negative but increases inequality when initial inequality is low. Studies (

Ashenafi & Dong, 2023;

De Haan & Sturm, 2017) have suggested that financial development may increase inequality, while findings on trade openness vary across different contexts (

Ashenafi & Dong, 2023;

Dorn et al., 2022). Previous studies have also documented the effects of education and government effectiveness on income inequality (

Blejer & Guerrero, 1990;

Crenshaw, 1992;

Odedokun & Round, 2001).

In short, while the literature documents aggregate-level economic growth through TFP, the further transfer of these benefits into society is unaddressed. A thorough examination of the relationships within differing economic situations is necessary, as

Stiglitz (

2007) has documented the uneven gains of free trade and economic globalization. Therefore, this study will seek to understand if income equality increases for developing, emerging, and advanced market countries in a similar manner to the increases in economic growth.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Variables and Source of Data

To analyze the effect of currency misalignment on income inequality, we use a dataset covering the period from 1998 to 2021, with key economic and control variables described in

Appendix B.

Currency misalignment will indicate whether the country undervalues (negative value) or overvalues its currency (positive value). Thus, a direct relationship is hypothesized between currency misalignment and the Gini coefficient, implying that a devalued currency leads to increased/decreased values of equality.

3.2. Handling of Missing Data

Countries with more than 16 missing observations (70% out of 24 total observations from 1998 to 2021) for any variable were excluded from the analysis. Missing values for the remaining countries were handled using a linear interpolation procedure.

The Gini index is the dependent variable of the model; however, some more-significant gaps were observed in relation to some values. To retain a big enough sample size for the analysis of our sample period from 1998 to 2021, we obtained data from 1990 to 2023 in order to increase the chance of obtaining a valid starting and ending value. In the rare case that no data were available at all within the early period (e.g., 1990 to 2000), we used a five-year backward-moving average to estimate the missing starting values. Similarly, if values were missing at the end of the study period, we used a regular five-year moving average to fill the gap. This approach was applied on a case-by-case basis, depending on each country’s data availability.

3.3. The Regression Equation

The estimated model is specified as follows:

Currency misalignment values indicate whether a country undervalues (negative values) or overvalues (positive values) its currency. A direct relationship is hypothesized between misalignment and the Gini coefficient, whereby an overvalued currency is expected to increase income inequality, while an undervalued currency may reduce it by supporting the tradable sector and employment.

3.4. Models Used

We examined the relationship between currency misalignment (MIS) and income inequality (Gini), using panel data regression methods including fixed-effects (FE) or random-effects (RE) regression models.

We used a fixed-effects (FE) model, which controls for unobserved, time-invariant characteristics that differ across countries, such as geography, cultural, or other institutional features, that may influence the inequality level. We also used a random-effects (RE) model when appropriate, which assumes that the unobserved country-specific effects are uncorrelated with the explanatory variables. We performed a Hausman test to determine whether FE or RE is more appropriate. In most cases, the test rejects the null hypothesis, which suggested that the FE models provide more consistent results for our data.

The regressions were applied to all countries, as well as to specific country groupings, to examine how currency misalignment affects income inequality across different types of countries. Two types of groupings are used—one based on development level (Advanced or Emerging and Developing, according to IMF classification) and the other based on income levels (High, Upper-Middle, Lower-Middle, and Low-Income, according to World Bank rankings). The use of two groupings allows us to test the robustness of the results across different classification criteria. For the IMF groupings, Emerging and Developing countries are combined into a single category due to inconsistencies in the IMF’s classification for these two groups over the study period. For the World Bank groupings, Lower-Middle Income and Low-Income countries are combined into a single group to increase the sample size for this group. These groupings are updated annually to ensure that the regressions reflect the correct classification for each country in each year.

4. Results and Discussion

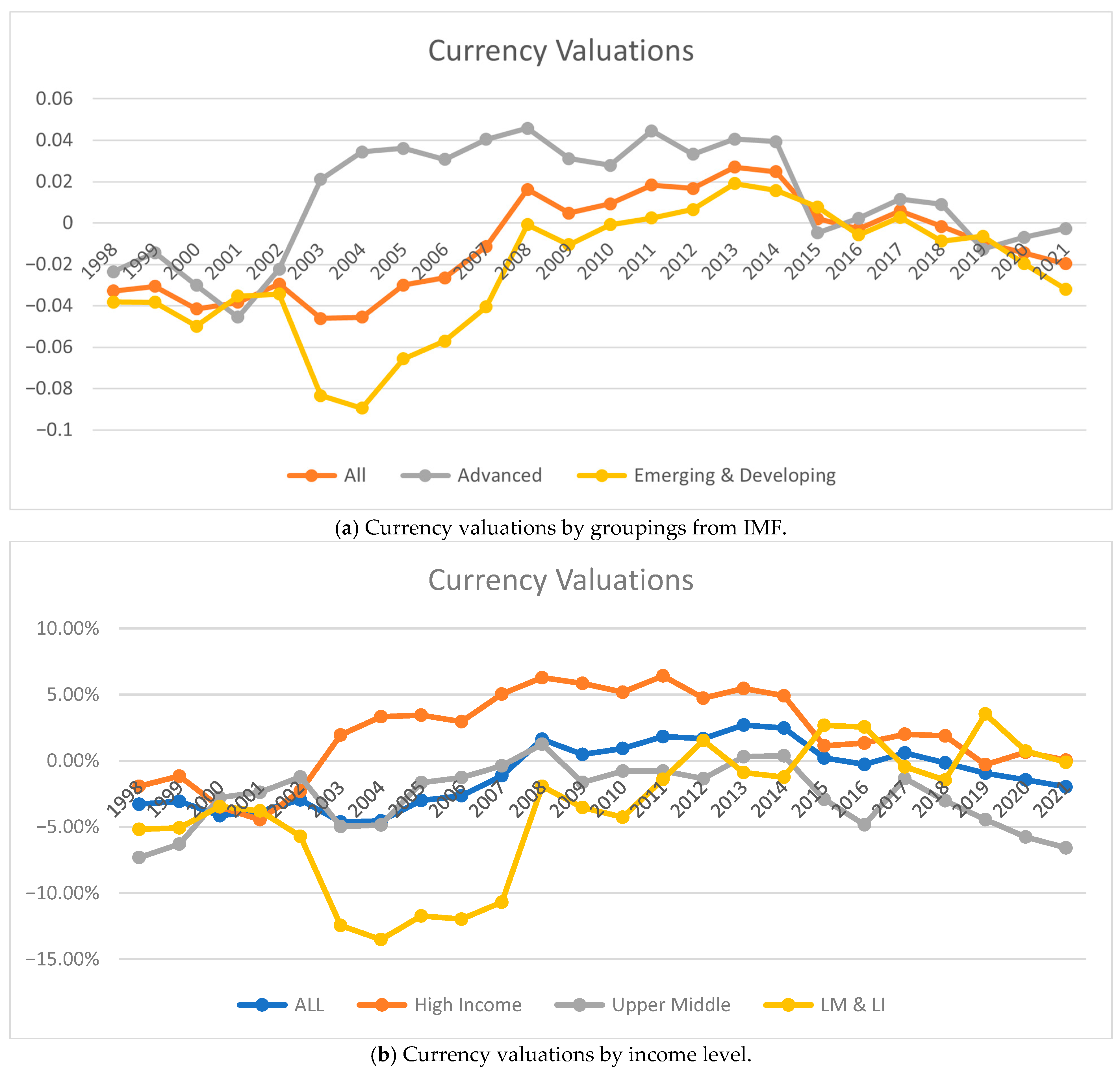

Figure 1 shows the average currency misalignment for different country groups from 1998 to 2018, using data from EQCHANGE. Advanced economies and high-income countries were generally more overvalued than other groups. In both development-level and income-level groupings, there was a clear pattern, whereby Emerging and Developing and Lower-Middle and Low-Income countries had periods of undervaluation, especially in the early 2000s. Over time, their currencies appreciated until around 2013, before shifting back toward undervaluation in later years. After 2014, all groups moved closer together, with mild undervaluation.

The groupings are not based on fixed sets of countries. They are updated each year, so a country may belong to different groups in different years depending on how it is classified at that time.

Table 1 shows a breakdown of the descriptive statistics for our variables across the entire sample and subgroups. On average, Emerging and Developing countries have a higher income inequality (mean Gini = 38.78) than Advanced countries (mean Gini = 31.96), along with lower average income, education, and financial development levels. Currency misalignment is more negative in Emerging and Developing economies, suggesting a higher tendency toward undervaluation. Inflation is also much higher and more volatile in Emerging and Developing countries, implying greater macroeconomic instability. These differences show the contrasting structural and economic conditions between the two groups.

Table 2 and

Table 3 show the findings from the fixed-effects and random-effects regression models. In the overall sample of 70 countries, the coefficient of MIS is positive and significant (1.128;

p = 0.041), indicating that greater currency misalignment (currency overvaluation) is associated with increased income inequality, while undervalued currencies are linked to reductions in inequality. GDP per capita is negatively associated with inequality, suggesting that as countries become wealthier, income inequality tends to decrease. In other words, economic growth may link to reduced income inequality, a finding that is consistent with parts of the literature.

Numerous studies have shown that currency undervaluation could stimulate economic growth, especially in developing countries.

Rodrik (

2008) explains that undervalued currencies help promote the tradable sector, which is usually the key mechanism for growth in developing countries, by making these industries more competitive. He theorizes that the growth caused by undervalued currencies in tradable sectors is a correction of two distinct distortions—the weak institutions that lead to poor contracting environments for investment, as well as the poor information, lack of coordination, and other market imperfections that can also hinder the tradable sector. However, undervalued currencies can provide an exogenous shock to the environment that helps overcome these two distortions, hence inducing economic growth.

Tipoy et al. (

2018) identified increases in total factor productivity (TFP) as a key driver of growth linked to undervalued currencies. As the demand for tradable goods increases, resources shift from the non-tradable to the tradable sector, boosting productivity.

Mbaye (

2013) explains this through three mechanisms: learning by doing, learning spillovers, and sectoral composition effects. These processes, which are gained from experience, external knowledge transfer, and the inherently higher productivity of tradables, are likely to occur together under currency undervaluation conditions.

McLeod and Mileva (

2011) show that a 10% undervaluation can raise annual TFP growth by 0.2% in developing countries.

On the other hand, the relationship between economic growth and income inequality has long been debated in the literature.

Kuznets (

1955) asserts that income inequality increases as a country industrializes but then peaks and declines with further development; however, this specific inverted U-shaped curve relationship received mixed empirical support from the current literature. Other studies provide mixed results on the linear relationship between GDP per capita and income equality, which can be negatively correlated, indicating that a higher income contributes to reducing inequality and alleviating poverty (

Naceur & Zhang, 2016); mixed results are reported by

Ashenafi and Dong (

2023),

Dorn et al. (

2022), and others.

Dollar (

2001) found that countries like India, Vietnam, and Uganda have recently increased efforts to open up their economies, which has resulted in faster growth and more poverty reduction.

In our analysis, GDP per capita has a negative significant relationship with inequality, supporting the view that growth is associated with reduced income disparities. When combined with the literature on currency undervaluation, a clear theoretical mechanism can be drawn—undervalued currencies are associated with growth and, in turn, growth is linked to reduced inequality. This provides a logical explanation for the observed pattern in our results, whereby undervaluation is linked to lower inequality, while overvaluation is linked to higher gaps, particularly in developing and emerging economies.

From a more direct and intuitive perspective, undervaluation is linked to increased employment and raised wages in labor-intensive tradable sectors, which often benefit lower-income workers. Job creation, income growth, and greater opportunities in those industries are likely to reduce inequality for the poorer groups. This interpretation is consistent with broader evidence that undervaluation plays a crucial role in structural transformation in lower-income countries (

Rodrik, 2008;

McLeod & Mileva, 2011;

Mbaye, 2013).

Many of the cited studies focus specifically on developing economies, where the tradable sector plays a critical role in employment and economic growth. Our own results confirm that Emerging and Developing economies, or the equivalent Upper-Middle and Lower-Middle Income groups, are the primary drivers of the observed relationship between currency undervaluation and equality in the full sample. In contrast, advanced and high-income countries show weaker and statistically insignificant effects.

Among other control variables, mean years of schooling (MYS) is significantly associated with lower income inequality, where increased education levels contribute to greater income equality. Government effectiveness generally reduces income inequality; however, the impact is not statistically significant. Inflation does not have a statistically significant effect on income inequality, which is in line with mixed findings in the existing body of literature. Trade openness has a mild effect on income inequality overall. This suggests that increased trade may benefit certain industries or population groups more than others, widening income gaps. This finding does not contradict the earlier conclusion about growth in the tradable sectors. While currency undervaluation is linked to tradable sector growth and reduced inequality in emerging and developing countries, broader trade openness, including both exports and imports, may still contribute to income disparities. This can occur when, for example, increased imports negatively impact domestic industries and workers. Financial development also has a mild effect on inequality overall.

The development-level groupings are shown in

Table 2. For Advanced economies, the coefficient of MIS is very small (−0.071) and not statistically significant. This suggests that currency misalignment does not have a meaningful relationship with income inequality in advanced countries. These economies are likely to have stronger financial systems and more stable institutions, which help reduce the effects of misalignment. Higher economic growth (GDP per capita) is also linked to lower inequality, but this effect is not statistically significant in the case of advanced economies.

In contrast, for Emerging and Developing economies, the effects of currency misalignment and GDP per capita on income inequality are similar to those observed in the full sample. Currency overvaluation is associated with higher income inequality, while undervaluation is associated with a lower one. Likewise, GDP per capita is negatively associated with inequality. These results may reflect that unlike Advanced economies, Emerging and Developing countries have income distributions that are more sensitive to changes in exchange rates and changes in wealth.

The income-level groupings are shown in

Table 3. Similarly to the Advanced economy group, the High-Income group shows a small, negative, and statistically insignificant coefficient on MIS. This suggests that currency misalignment does not have a meaningful relationship with income inequality in High-Income countries. These countries likely have strong financial systems, economies, and institutions, which help reduce the impact of exchange rate changes on income distribution.

In the Upper-Middle-Income group, the effects of MIS and GDP per capita on inequality are similar to those seen in Emerging and Developing economies and the full sample. These countries are often undergoing rapid structural changes, which may make them more sensitive to shifts in exchange rates and economic growth. As a result, currency overvaluation in this group is associated with rising inequality, while undervaluation is associated with a declining one.

In contrast, the Lower-Middle-Income and Low-Income groups show different patterns. In these countries, undervalued currencies are associated with higher inequality, and economic growth is also linked to worsened income distribution. While this does not contradict the broader idea that undervaluation is associated with growth, the difference may lie in how growth is distributed. In the early stages of development, the benefits of growth might go to a small segment of the population, such as those who possess information and capital, while poorer or rural populations are not equally benefited.

This outcome is consistent with the Kuznets hypothesis (1955), which suggests that inequality tends to increase during the early phases of industrialization. Over time, as economies grow and more people gain access to education, jobs, and social benefits, inequality may begin to decline. In the Lower-Income groups in our study, however, this redistribution may not yet be taking place, so growth and undervaluation may be linked to greater inequality in the short term.

5. Conclusions

Previous research highlights the positive effects of currency undervaluation on economic growth. This paper extends that discussion by examining whether such growth also contributes to greater income equality. Our findings show that currency undervaluation is generally associated with lower income inequality across countries, though the impact varies by development level.

Undervalued currencies are associated with economic growth, which, in turn, is linked to lower inequality. This pattern is particularly strong in Emerging and Upper-Middle-Income economies, where tradable sectors play a critical role in economic growth and are more responsive to exchange rate changes. Currency undervaluation is associated with increased employment and raised wages in labor-intensive tradable sectors, which often benefit lower-income workers. Job creation, income growth, and greater opportunities in those industries are likely to reduce inequality for the poorer groups. This interpretation is consistent with broader evidence that undervaluation plays a crucial role in structural transformation in developing countries (

Rodrik, 2008;

McLeod & Mileva, 2011;

Mbaye, 2013).

In contrast, Lower-Income countries experience a different pattern. In these countries, growth associated with undervaluation may be initially linked to inequality. This finding aligns with

Kuznets’ (

1955) theory of the inverted U-shaped curve, where inequality rises during the early stages of industrialization but declines as countries become more developed. Specifically, our results suggest that undervalued currencies are linked to inequality in Low- and Lower-Middle-Income countries, but this trend reverses as nations move into the Upper-Middle-Income category.

For Advanced economies in IMF groupings or Higher-Income nations in World Bank groupings, currency misalignment does not have a significant relationship with income inequality. These economies are likely to have stronger financial systems and more stable institutions, which reduce the effects of misalignment.

This study uses two methods to group countries—by development level (from the IMF) and by income level (from the World Bank)—to check if the results stay consistent. Since similar patterns were found in both groupings, the findings appear to be robust. This shows that the link between currency undervaluation, growth, and income inequality depends on a country’s stage of development.

Overall, the results suggest that currency undervaluation may be associated with both growth and equity. However, this relationship appears to vary with a country’s stage of development. To ensure that the benefits of growth are more widely shared, especially in earlier development stages, governments may consider policies that improve access to education, quality jobs, and social protection. These efforts may help growth be associated with greater income equality.

At the same time, policymakers in emerging markets need to be aware of the risks that come with managing exchange rates. While undervaluation can be associated with growth and lower inequality, it may also carry risks if not supported by strong economic policies. To manage these risks, countries may consider strong tools for capital, inflation controls, etc. In this way, the benefits of an undervalued currency may be accompanied by growth and more income equality while keeping the economy stable.