Determinants of Crowdfunding Success in Africa: An Exploratory Perspective on Incentive Rewards and Beyond

Abstract

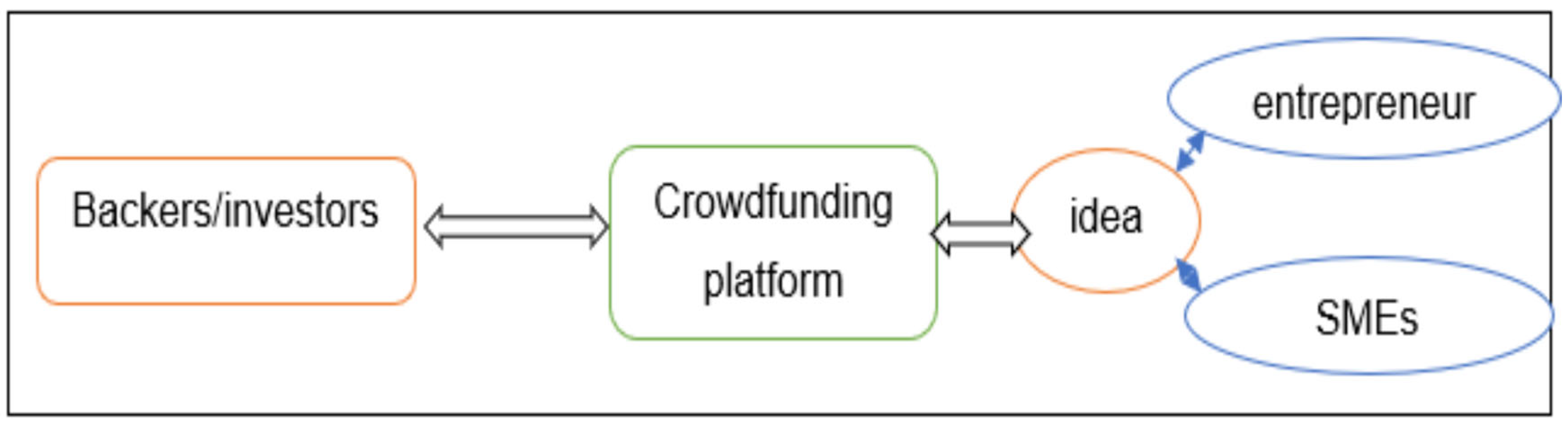

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and the Theoretical Framework

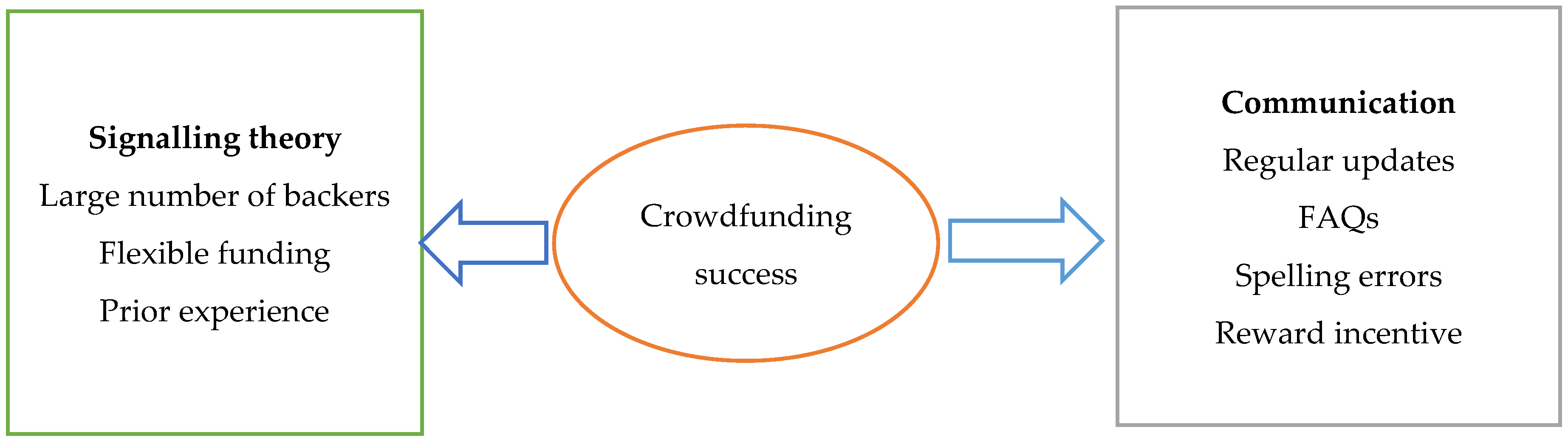

2.1. Information Asymmetry Theory

2.2. Signalling Theory

2.3. Expectancy Theory

2.4. Attribution Theory

3. Research Method and Materials

4. Research Findings and Discussion

5. Implications of the Study

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbasi, D., Mahdieh, O., & Shahsavari, F. (2024). Identifying factors affecting the success of startups: A phenomenological study. Journal of Entrepreneurship Development, 16(4), 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aideyan, S. N. (2023). Reward-based crowdfunding in nigeria: Exploring the mechanism of trust [Ph.D. thesis, Coventry University]. Available online: https://pure.coventry.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/82580062/Aideyan2023PhD.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Baah-Peprah, P., & Shneor, R. (2022). A trust-based crowdfunding campaign marketing framework: Theoretical underpinnings and big-data analytics practice. International Journal of Big Data Management, 2(1), 119453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, H. (2021). Modelling the acceptance of e-learning during the pandemic of COVID-19: A study of South Korea. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(2), 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrova, A., Ņečiporuka, M., & Lublóy, Á. (2024). Success factors of real estate crowdfunding projects: Evidence from Spain. Society and Economy, 46(2), 194–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafera, J., & Kleinert, S. (2023). Signaling theory in entrepreneurship research: A systematic review and research agenda. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 47(6), 2419–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardino, S., Santos, J. F., & Oliveira, S. (2021). Financing nascent entrepreneurs by reward-based crowdfunding: Lessons from Indiegogo campaigns. In Handbook of research on nascent entrepreneurship and creating new ventures (pp. 228–252). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilau, J. J., & Pires, J. (2018). What drives the funding success of reward-based crowdfunding campaigns? Poslovna Izvrsnost, 12(2), 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, F. A. S., Usman, S. M., Usman, M., & Hussain, K. (2020). The effects of creator credibility and backer endorsement in donation crowdfunding campaigns success. Baltic Journal of Management, 15, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z., Zhang, P., & Han, X. (2021). The inverted U-shaped relationship between crowdfunding success and reward options and the moderating effect of price differentiation. China Finance Review International, 11(2), 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, T. (2018). Expectations, self-determination, reward-seeking behaviour and well-being in Malta’s financial services sector [Doctoral dissertation, University of Leicester]. Available online: https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/Expectations_Self-Determination_Reward-Seeking_Behaviour_and_Well-Being_in_Malta_s_Financial_Services_Sector/10235513 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Cappa, F., Rosso, F., & Hayes, D. (2019). Monetary and social rewards for crowdsourcing. Sustainability, 11(10), 2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonara, N. (2021). The role of geographical clusters in the success of reward-based crowdfunding campaigns. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 22(1), 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, E. J., Serwaah, P., Baah-Peprah, P., & Shneor, R. (2020). Crowdfunding in Africa: Opportunities and challenges. In R. Shneor, L. Zhao, & B. T. Flåten (Eds.), Advances in crowdfunding: Research and practice (pp. 319–339). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-Y., Chang, J.-R., Chen, L.-S., & Shen, E.-L. (2022). The key successful factors of video and mobile game crowdfunding projects using a lexicon-based feature selection approach. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, 13, 3083–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. D. (2023). Crowdfunding for social ventures. Social Enterprise Journal, 19(3), 256–276. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/1750-8614.htm (accessed on 22 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Zhou, S., Jin, W., & Chen, S. (2023). Investigating the determinants of medical crowdfunding performance: A signaling theory perspective. Internet Research, 33(3), 1134–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B. L., Certo, S. T., Ireland, R. D., & Reutzel, C. R. (2011). Signaling theory: A review and assessment. Journal of Management, 37(1), 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, F. J., & Lee, K. C. (2022). Exploring investors’ expectancies and its impact on project funding success likelihood in crowdfunding by using text analytics and Bayesian networks. Decision Support Systems, 154, 113695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambanemuya, H. K., & Horvát, E.-Á. (2021). A multi-platform study of crowd signals associated with successful online fundraising. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehdashti, Y., Namin, A., Ratchford, B. T., & Chonko, L. B. (2022). The unanticipated dynamics of promoting crowdfunding donation campaigns on social media. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 57(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiray, M., Burnaz, S., & Aslanbay, Y. (2019). The crowdfunding market, models, platforms, and projects. In Crowdsourcing: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications (pp. 115–151). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L., Ye, Q., Xu, D., Sun, W., & Jiang, G. (2022). A literature review and integrated framework for the determinants of crowdfunding success. Financial Innovation, 8(1), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, F., & Tenca, F. (2024). The role of entrepreneur’s experience and company control in influencing the credibility of passion as a signal in equity crowdfunding. Venture Capita, 26(2), 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Felipe, I. J., Mendes-Da-Silva, W., Leal, C. C., & Santos, D. B. (2022). Reward crowdfunding campaigns: Time-to-Success analysis. Journal of Business Research, 138, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durojaiye, A. T., Ewim, C. P.-M., & Igwe, A. N. (2024). Developing a crowdfunding optimization model to bridge the financing gap for small business enterprises through data-driven strategies. International Journal of Scholarly Research and Reviews, 5(2), 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efrat, K., Gilboa, S., & Sherman, A. (2020). The role of supporter engagement in enhancing crowdfunding success. Baltic Journal of Management, 15(2), 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbeiss, M., Hartmann, S. A., & Hornuf, L. (2023). Social media marketing for equity crowdfunding: Which posts trigger investment decisions? Finance Research Letters, 52, 103370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrashidy, Z., Haniffa, R., Sherif, M., & Baroudi, S. (2024). Determinants of reward crowdfunding success: Evidence from COVID-19 pandemic. Technovation, 132, 102985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X. (2024). Can crowdfunding creators learn from previous experiences to have a better future financing performance? Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 39(2), 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J. (2019). Thank you for being a friend: The roles of strong and weak social network ties in attracting backers to crowdfunded campaigns. Information Economics and Policy, 49, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguli, I., Huysentruyt, M., & Le Coq, C. (2021). How do nascent social entrepreneurs respond to rewards? A field experiment on motivations in a grant competition. Management Science, 67(10), 6294–6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A. S., & George, A. S. H. (2023). Leveraging the ego: An examination of brand strategies that appeal to consumer vanity. Partners Universal International Research Journal, 2(3), 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J., Pavlou, P. A., & Zheng, Z. (2020). On the use of probabilistic uncertain rewards on crowdfunding platforms: The case of the lottery. Information Systems Research, 32(1), 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoriades, A., & Themistocleous, C. (2025). Improving Crowdfunding Decisions Using Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Sustainability, 17(4), 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haasbroek, F., & Ungerer, M. (2020). Theory versus practise: Assessing reward-based crowdfunding theory through a South African case study. South African Journal of Business Management, 51(1), a2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J. R., & Porter, L. W. (1968). Expectancy theory predictions of work effectiveness. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 3(4), 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). The use of partial least squares (PLS) to address marketing management topics. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 135–138. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2228902 (accessed on 21 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.-C., Chiu, C. L., Mansumitrchai, S., Yuan, Z., Zhao, N., & Zou, J. (2021). The influence of signals on donation crowdfunding campaign success during COVID-19 crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohen, S., Hüning, C., & Schweizer, L. (2025). Reward-based crowdfunding—A systematic literature review. Management Review Quarterly, 4, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, C., Rose, S., & Kaminski, J. (2022). The pervasive role of campaign and product-related uncertainties in inhibiting crowdfunding success. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(8), 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, J. (2006). The rise of crowdsourcing. Wired Magazine, 14(6), 176–183. Available online: https://www.wired.com/2006/06/crowds/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Huang, S., Pickernell, D., Battisti, M., & Nguyen, T. (2022). Signalling entrepreneurs’ credibility and project quality for crowdfunding success: Cases from the Kickstarter and Indiegogo environments. Small Business Economics, 58(4), 1801–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z., Ouyang, J., Huang, X., Yang, Y., & Lin, L. (2021). Explaining donation behavior in medical crowdfunding in social media. Sage Open, 11(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaila, B. (2023). The statse of crowdfunding in Africa and its potential impact: A literature review. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 12(5), 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jáki, E., Csepy, G., & Kovács, N. (2022). Conceptual framework of the crowdfunding success factors: Review of the academic literature. Acta Oeconomica, 72(3), 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H., Wang, Z., Yang, L., Shen, J., & Hahn, J. (2021). How rewarding are your rewards? A value-based view of crowdfunding rewards and crowdfunding performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(3), 562–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreilkamp, N., Matanovic, S., Schmidt, M., & Wöhrmann, A. (2023). How executive incentive design affects risk-taking: A literature review. Review of Managerial Science, 17(7), 2349–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G., & Wang, J. (2019). Threshold effects on backer motivations in reward-based crowdfunding. Journal of Management Information Systems, 36(2), 546–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., & Wang, N. (2024). Fundraiser engagement, third-party endorsement and crowdfunding performance: A configurational theory approach. PLoS ONE, 19(8), e0308717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y., Liu, F., Fan, W., Lim, E. T. K., & Liu, Y. (2022). Exploring the impact of initial herd on overfunding in equity crowdfunding. Information & Management, 59(3), 546–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.-P., Wu, S. P.-J., & Huang, C.-C. (2019). Why funders invest in crowdfunding projects: Role of trust from the dual-process perspective. Information & Management, 56(1), 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Ben, S., & Zhang, R. (2023). Factors affecting crowdfunding success. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 63(2), 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S., Hua, Y., Li, D., & Wang, Y. (2022). Proposing customers economic value or relational value? A study of two stages of the crowdfunding project. Decision Sciences, 53(4), 712–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamaro, L. P., & Sibindi, A. B. (2023). Role of social networks in crowdfunding performance during the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa. Journal of Risk Analysis and Crisis Respons, 13(3), 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamaro, L. P., & Sibindi, A. B. (2024). The Influence of fixed and flexible funding mechanisms on reward-based crowdfunding success. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(10), 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollick, E. (2014). The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, F., Bianco, S., & Pescitelli, C. (2019). Integrated Communication for Start-Ups Toward an Innovative Framework. In P. De Vincentiis, F. Culasso, & S. A. Cerrato (Eds.), The future of risk management, volume II: Perspectives on financial and corporate strategies (pp. 361–401). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moy, N., Chan, H. F., & Torgler, B. (2018). How much is too much? The effects of information quantity on crowdfunding performance. PLoS ONE, 13(3), e0192012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngalim, L., & Togan Eğrican, A. (2023). Private equity industry in Africa: Firm survival and growth. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1, 1–29. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4340228 (accessed on 16 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Omenguélé, R. G., & Mbouolang, Y. C. (2022). When the social networks and internet come to the rescue of entrepreneurs: The problematic of crowdfunding in Africa. The Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance (JEF), 24(1), 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P. K. (2023). The acceptable R-square in empirical modelling for social science research. In Social research methodology and publishing results: A guide to non-native English speakers (pp. 134–143). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, A., & Wirtz, P. (2022). Experts in the crowd and their influence on herding in reward-based crowdfunding of cultural projects. Small Business Economics, 58(1), 419–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkow, F. (2022). The impact of common success factors on overfunding in reward-based crowdfunding: An explorative study and avenues for future research. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 18(1), 131–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posch, L., Mladenow, A., & Strauss, C. (2022). Reward-based crowdfunding: Successful signaling from an entrepreneur (pp. 999–1014). COLINS. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Christine-Strauss-2/publication/362861372_Reward-based_Crowdfunding_successful_signaling_from_an_entrepreneur/links/63049d57aa4b1206facf1fed/Reward-based-Crowdfunding-successful-signaling-from-an-entrepreneur.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Regner, T., & Crosetto, P. (2021). The experience matters: Participation-related rewards increase the success chances of crowdfunding campaigns. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 30(8), 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Navarrete, S., Palacios-Marqués, D., Lassala, C., & Ulrich, K. (2021). Key factors of information management for crowdfunding investor satisfaction. International Journal of Information Management, 59, 102354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Garnica, G., Gutiérrez-Urtiaga, M., & Tribo, J. A. (2024). Signaling and herding in reward-based crowdfunding. Small Business Economics, 64, 889–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauermann, H., Franzoni, C., & Shafi, K. (2019). Crowdfunding scientific research: Descriptive insights and correlates of funding success. PLoS ONE, 14(1), e0208384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaife, W. (2023). Disaster fundraising: Readiness matters. In Philanthropic response to disasters (pp. 44–75). Policy Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F., Ma, L., Choi, T.-M., & Xue, W. (2021). Quality and pricing decisions for reward-based crowdfunding: Effects of moral hazard. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneor, R., & Vik, A. A. (2020). Crowdfunding success: A systematic literature review 2010–2017. Baltic Journal of Management, 15, 149–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneor, R., Zhao, L., & Goedecke, J. F. M. (2023). On relationship types, their strength, and reward crowdfunding backer behavior. Journal of Bussiness Research, 154, 113294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L., Silva, N. F., & Rosa, T. (2020). Success prediction of crowdfunding campaigns: A two-phase modeling. International Journal of Web Information Systems, 16(4), 387–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solodoha, E. (2024). How much is too much? The impact of update frequency on crowdfunding success. Administrative Sciences, 14(12), 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani Delgosha, M., Hajiheydari, N., & Olya, H. (2024). A person-centred view of citizen participation in civic crowdfunding platforms: A mixed-methods study of civic backers. Information Systems Journal, 34, 1626–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Berger, R., Yosipof, A., & Barnes, B. R. (2019). Mining and investigating the factors influencing crowdfunding success. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 148, 119723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soublière, J.-F., & Gehman, J. (2020). The legitimacy threshold revisited: How prior successes and failures spill over to other endeavors on Kickstarter. Academy of Management Journal, 63(2), 472–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. (2002). Signaling in retrospect and the informational structure of markets. American Economic Review, 92(3), 434–459. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3083350 (accessed on 13 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Steigenberger, N. (2017). Why supporters contribute to reward-based crowdfunding. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 23(2), 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimić Šarić, M. (2021). Determinants of crowdfunding success in Central and Eastern European countries. Management: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 26(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telve, L. (2019). Building a successful crowdfunding campaign: What marketing factors do really matter for your project? [Doctoral dissertation, Catolica Lisbon Business Economic]. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2925087173?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Theerthaana, P., & Lysander Manohar, H. (2021). How a doer persuade a donor? Investigating the moderating effects of behavioral biases in donor acceptance of donation crowdfunding. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 15(1), 243–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2023). The impact of the reward scheme design on crowdfunding performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 194, 122730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschoore, J. R., & Araújo, M. D. M. (2020). The effect of reward strategies on the success of crowdfunding campaigns. RAM. Revista de Administração Mackenzie, 214, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. Wiley. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1964-35027-000 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Wachira, V. K. (2021). Crowdfunding in Kenya: Factors for successful campaign. Public Finance Quarterly, 3, 413–428. Available online: http://ir.kabarak.ac.ke/handle/123456789/901 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Wang, W., Xu, Y., Wu, Y. J., & Goh, M. (2022). Linguistic understandability, signal observability, funding opportunities, and crowdfunding campaigns. Information & Management, 59(2), 103591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessel, M., Gleasure, R., & Kauffman, R. J. (2021). Sustainability of rewards-based crowdfunding: A quasi-experimental analysis of funding targets and backer satisfaction. Journal of Management Information Systems, 38(3), 612–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, C., Yu, H., & Huang, H. (2020). Predicting the success of entrepreneurial campaigns in crowdfunding: A spatio-temporal approach. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Zhang, M., Shen, Y., Liu, N., & Li, Y. (2023). How do project updates influence fundraising on online medical crowdfunding platforms? Examining the dynamics of content updates. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 71, 9135–9149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Li, Y., Calic, G., & Shevchenko, A. (2020). How multimedia shape crowdfunding outcomes: The overshadowing effect of images and videos on text in campaign information. Journal of Business Research, 117, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasar, B. (2021). The new investment landscape: Equity crowdfunding. Central Bank Review, 21(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y., & Shen, W. (2024). Signalling theory in charity-based crowdfunding: Investigating the effects of project creator characteristics and text linguistic style on fundraising performance. Heliyon, 10(4), e25756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X., Tao, X., Ji, B., Wang, R., & Sörensen, S. (2023). The success of cancer crowdfunding campaigns: Project and text analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e44197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Wang, X., Wang, D., Xiao, Q., & Deng, Z. (2024). How the linguistic style of medical crowdfunding charitable appeal influences individuals’ donations. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 203, 123394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H., Xu, B., Zhang, M., & Wang, T. (2018). Sponsor’s cocreation and psychological ownership in reward-based crowdfunding. Information Systems Journal, 28(6), 1213–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zribi, S. (2022). Effects of social influence on crowdfunding performance: Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dependent Variables | Measurements |

|---|---|

| Success (SC) | The binary variable of 1 if the target amount was obtained and 0 otherwise. |

| Independent variables | |

| Reward incentive (REW) | The binary variable of 1 if a campaign provides rewards, and 0 otherwise. |

| Prior experience (EXP) | The dummy variable is 1 if the project creator has created more than two crowdfunding campaigns and 0 otherwise. |

| Frequently asked questions (FAQs) | Number of frequently asked questions on the project between the entrepreneur and the backers (transformed into a log). |

| Flexible funding (FXF) | The binary variable of 1 if it is flexible funding and 0 if it is fixed funding. |

| Large number of backers (BCK) | The number of supporters who contributed to the project (transformed into a log). |

| Spelling errors (SPRs) | The dummy variable is 1 if there are spelling errors on the website and 0 otherwise. |

| Regular updates (UPDs) | The number of days for a campaign to raise funds (transformed into a log). |

| Variables | Obs | Mean | Median | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success | 854 | 0.1604 | 0.0000 | 0.7334 | 0.0000 | 14.5850 | 12.6177 | 216.6589 |

| Reward | 854 | 0.8665 | 1.0000 | 0.3403 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | −2.1553 | 5.6453 |

| EXP | 854 | 0.1967 | 0.0000 | 0.3978 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.5259 | 3.3282 |

| FAQ | 854 | 0.0995 | 0.0000 | 0.9114 | 0.0000 | 13.000 | 10.5589 | 120.6652 |

| FXF | 854 | 0.7611 | 1.0000 | 0.4266 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | −1.2248 | 2.5001 |

| BCK | 854 | 19.581 | 0.0000 | 118.2678 | 0.0000 | 2438.000 | 13.6361 | 235.6418 |

| SPR | 854 | 0.2810 | 0.0000 | 0.4498 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9743 | 1.9492 |

| UPD | 854 | 0.91803 | 0.0000 | 3.1530 | 0.0000 | 36.0000 | 5.60325 | 42.0437 |

| Observations | VIF | CR | REW | EXP01 | FAQ | FXF | BCK | SPR | UPD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | DV | 1.000 | |||||||

| REW | 1.1123 | 0.077 ** | 1.000 | ||||||

| EXP | 1.1077 | 0.0958 ** | 0.194 *** | 1.000 | |||||

| FAQ | 1.0841 | 0.151 *** | 0.0429 | 0.0591 * | 1.000 | ||||

| FXF | 1.0910 | −0.209 *** | −0.058 * | −0.098 *** | −0.195 *** | 1.000 | |||

| BCK | 1.23132 | 0.422 *** | 0.059 * | 0.175 *** | 0.195 *** | −0.147 *** | 1.000 | ||

| SPR | 1.08411 | −0.0278 | 0.245 *** | 0.077 ** | −0.025 | 0.0936 ** | −0.0463 | 1.000 | |

| UPD | 1.36362 | 0.4765 *** | 0.1143 *** | 0.241 *** | 0.296 *** | −0.231 *** | 0.4160 *** | −0.027 | 1.000 |

| Hypothesis Variables | Coefficient (β) | Std. Error | Prob |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Reward incentive | 0.202971 | 0.381730 | 0.5949 |

| H2: Prior experience | 0.218184 | 0.218931 | 0.3190 |

| H3: Frequently asked questions | −0.034899 | 0.088288 | 0.6926 |

| H4: Flexible funding | −0.634501 | 0.192368 | 0.0010 *** |

| H5: Large number of backers | 0.030202 | 0.003268 | 0.0000 *** |

| H6: Spelling errors | −0.2145 | 0.01777 | 0.3429 |

| H7: Regular updates | 0.033746 | 0.027196 | 0.2147 |

| C | −1.958281 | 0.372702 | 0.0000 |

| 0.586165 | |||

| Number of observations | 856 | ||

| Prob(LR statistic) | 0.00000 |

| Hypothesis | Support |

|---|---|

| H1: A reward incentive has a positive effect on a crowdfunding campaign, increasing the probability of its success. | Not supported |

| H2: An entrepreneur’s prior experience has a positive effect on their crowdfunding campaign, increasing the probability of its success. | Not supported |

| H3: Frequently asked questions have a positive impact on a crowdfunding campaign, increasing the possibility of its success. | Not supported |

| H4: The flexible funding mechanism has a negative effect on potential crowdfunding success. | supported |

| H5: A large number of backers has a significant and positive effect on a crowdfunding campaign, increasing the probability of its success. | Supported |

| H6: The presence of spelling errors in presenting a crowdfunding project has a detrimental effect on its possible success. | Not supported |

| H7: Regular updates have a significant and positive effect on the success of a crowdfunding campaign. | Not supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mamaro, L.P. Determinants of Crowdfunding Success in Africa: An Exploratory Perspective on Incentive Rewards and Beyond. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090478

Mamaro LP. Determinants of Crowdfunding Success in Africa: An Exploratory Perspective on Incentive Rewards and Beyond. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(9):478. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090478

Chicago/Turabian StyleMamaro, Lenny Phulong. 2025. "Determinants of Crowdfunding Success in Africa: An Exploratory Perspective on Incentive Rewards and Beyond" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 9: 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090478

APA StyleMamaro, L. P. (2025). Determinants of Crowdfunding Success in Africa: An Exploratory Perspective on Incentive Rewards and Beyond. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(9), 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090478