Credit-Market Cyclicality and Unemployment Volatility

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Cyclical costs of creditors’ search for financing opportunities generates cyclical tightness in the credit market, which drives matches between creditors and entrepreneurs that manage firms looking to recruit workers.

- I begin the analysis by establishing and investigating the model’s unique steady state. This allows me to calibrate the model by matching statistics on average labor-market tightness and job finding (Pissarides, 2009). The calibration does not rely on the idea that a marginal worker is indifferent between nonwork and employment. The steady state serves as a precursor to analyzing local dynamics and the algorithm used to find a nonlinear solution.

- Under the assumption that real wages are fixed, I investigate local dynamics. When the credit costs are acyclical, as in Petrosky-Nadeau and Wasmer (2013), the percent away labor-market tightness is from its steady state can be expressed as the sum of future productivity fluctuations. The effect is modulated by the factor . The term is what Ljungqvist and Sargent (2017) call the fundamental surplus. This amount deducts from worker productivity, x, the (fixed) wage, and the appropriately accounted flow cost of search for credit, k. Fundamental surplus is “an upper bound on resources that the invisible hand can allocate to vacancy creation” (Ljungqvist & Sargent, 2017, p. 2638). Fluctuations in labor-market tightness will be large if is small. This will happen when k is large. Unambiguously, k amplifies fluctuations in labor-market tightness and therefore unemployment. When the cost of credit is cyclical, however, two additional terms affect fluctuations in labor-market tightness.

- The first term has to do with job creation costs. If credit costs are procyclical, then an increase in productivity will be moderated by an increase in the cost of job creation. This term reduces cyclicality.

- The second term has to do with the amplification channel associated with production. An increase in x is associated with an increase in k, which can keep fundamental surplus small. This term increases cyclicality.

- Finally, the terms indicate that the relationships can be reversed. In general, the relationship between credit costs and labor-market dynamics is complex.

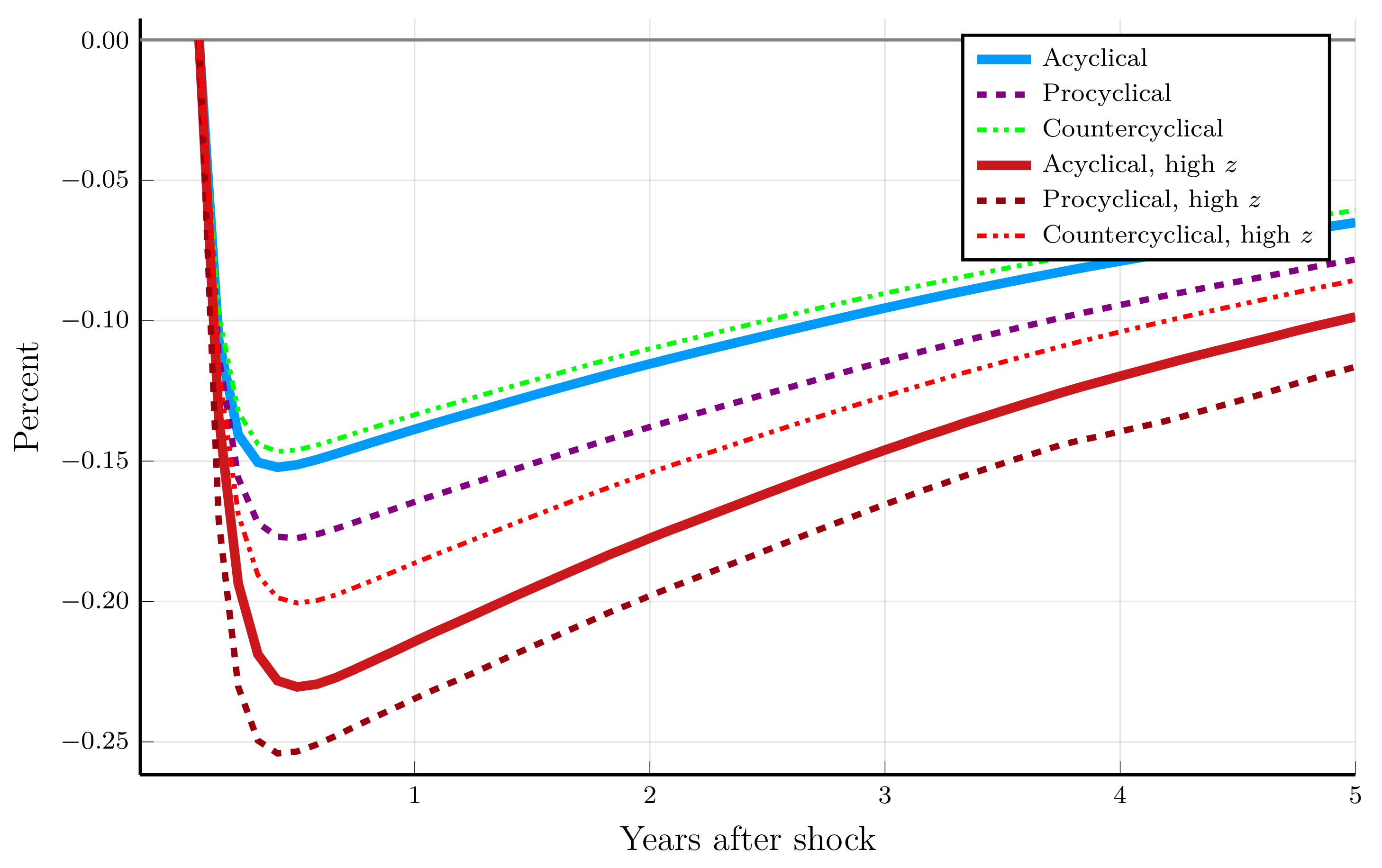

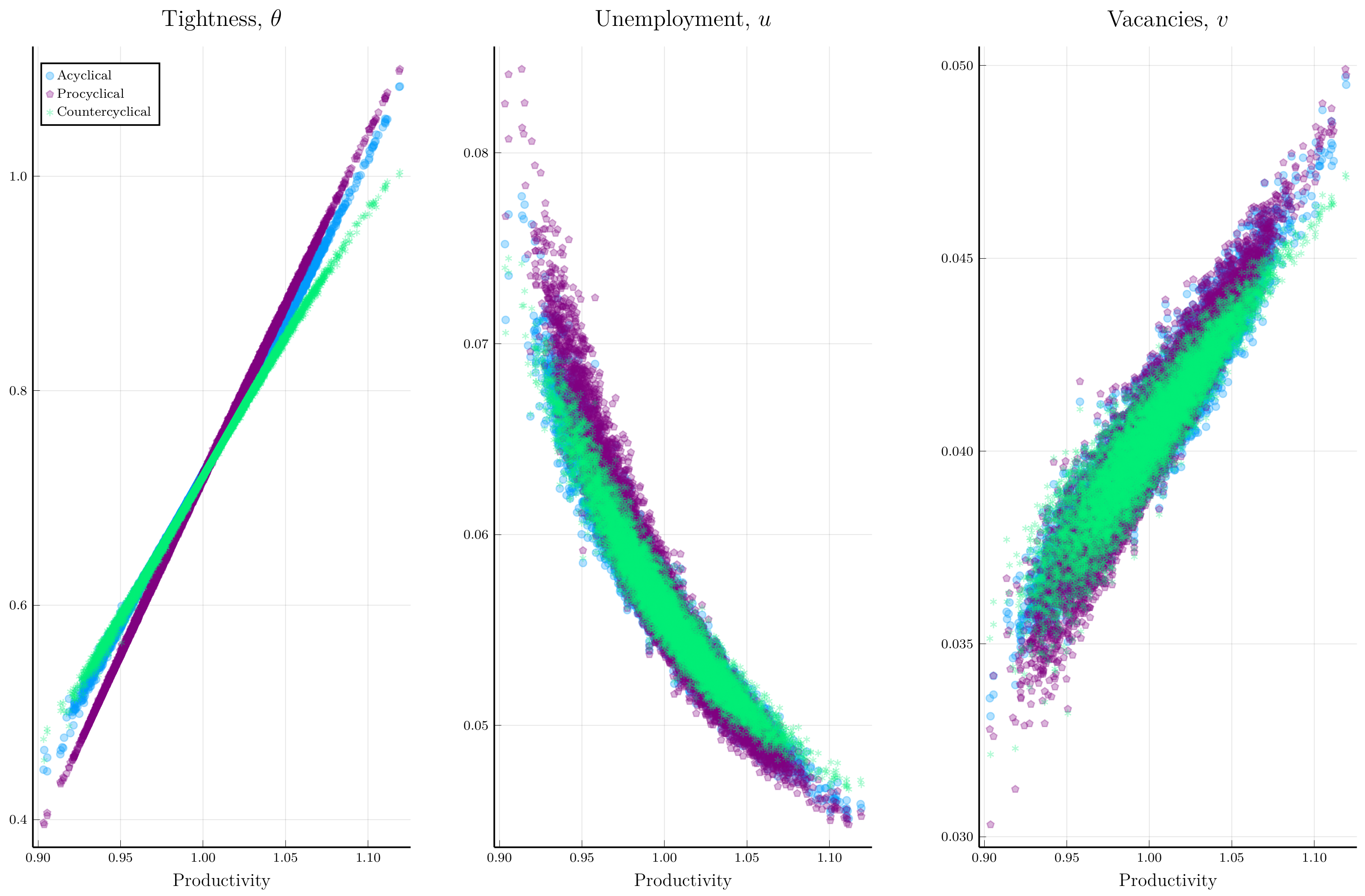

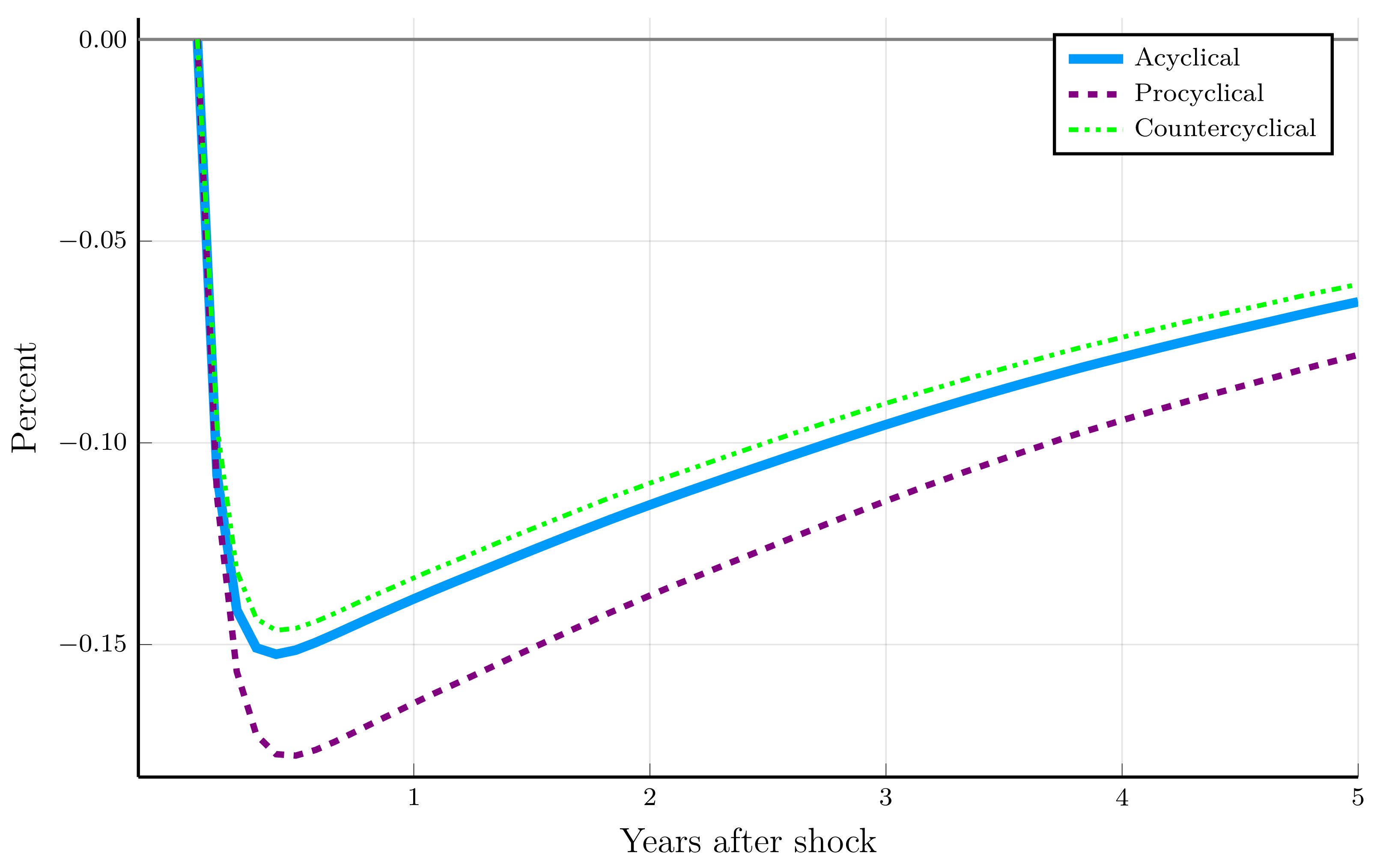

- A nonlinear solution method allows me to compare ergodic distributions from economies indexed by the cyclicality of credit costs. Numerical exercises indicate that for a standard set of parameter values,

- procyclical costs magnify the response of unemployment to productivity changes, and

- countercyclical costs minify the response of unemployment to productivity changes.

2. Economic Environment: Search for Work and Search for Credit

2.1. The Technology of Search

2.1.1. Matching in the Credit Market

2.1.2. Matching in the Labor Market

2.1.3. A Beveridge-Curve Relationship

2.2. Bellman Equations That Characterize the Economy

2.2.1. Bellman Equations for Entrepreneurs

2.2.2. Bellman Equations for Creditors

2.2.3. Bellman Equations for Workers

2.3. Main Idea: The Cost of Credit, the Notion of a Firm, and the Fundamental-Surplus Fraction

2.4. Job Creation

2.4.1. Interpreting the Cost of Creating a Job

2.4.2. A Dynamic Condition for Labor-Market Tightness

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Unique Steady-State Equilibrium

3.1.1. Steady State

3.1.2. Local Dynamics

3.2. Quantifying the Credit-Cost Channel

3.2.1. Algorithm

3.2.2. Calibration

3.2.3. Quantifying How Credit-Market Cyclicality Affects Labor-Market Dynamics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- procyclical credit costs magnify unemployment volatility, while

- countercyclical credit costs minify unemployment volatility.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Deriving the Expected Cost of Search

Appendix B. Job Creation

Appendix B.1. Deriving the Dynamic Condition for Job Creation

Appendix B.2. The Steady-State Job-Creation Condition

Appendix C. An Expression for the Wage Rate

Appendix D. Comparative Statics Demonstrate Properties of DMP Models and Robustness

| 1 | Daley et al. (2024) point out the pervasiveness of due diligence. They cite work by Lajoux and Elson (2011) and Cole et al. (2016) that documents the prevalence and costs of due diligence. Huang et al. (2023) document the labor costs of due diligence associated with mergers and acquisitions. If screening requires effort, then creditors’ flow cost of search can be thought of as costly effort, analogous to Shimer’s (2010) search-and-matching model in which a firm must devote some of its workforce to recruitment in order to hire an employee. Effort costs associated with screening are likely to be procyclical. |

| 2 | Ottonello and Song (2022) provide evidence consistent with the idea that financial intermediaries have greater access to funds in good states of the economy. They use high-frequency shocks to identify surprises in the market value of 18 financial intermediaries’ net worth. These financial shocks propagate to nonfinancial firms, but the propagation depends on the state of the aggregate economy, suggesting that financial intermediaries have access to more resources in good states. |

| 3 | Stein (2003) and Hall (2011) provide entry points to the the vast literature on financial markets. A recent example of how composition affects macroeconomic dynamics is provided by Guo et al. (2025). They document how a typical firm’s stock price falls by 1.2 percent on the day the firm announces its intent to sell equity and by 2.3 percent the following day. This evidence is interpreted as the effect of the firm’s revelation of private information. Private information creates a lemons-type problem, whereby firms need to signal their quality, making composition an important variable. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Research related to unemployment volatility includes work by Barnichon (2010); Brügemann and Moscarini (2010); Christiano et al. (2021); Eyigungor (2010); Garín and Lester (2019); Gertler and Trigari (2009); Gomme and Lkhagvasuren (2015); Hagedorn and Manovskii (2008); Hall (2005, 2017); Hall and Milgrom (2008); Kehoe et al. (2023); Kokonas (2023); Ljungqvist and Sargent (2017, 2021); Mortensen and Nagypál (2007); Petrosky-Nadeau (2014); Pissarides (2009); Rogerson and Shimer (2011); Ryan (2024); Silva and Toledo (2009, 2013); Wang (2023). |

| 6 | The vacancy rate is defined through the normalization of the labor force. If is the size of the labor force in period t, the number of matches per period is . Because exhibits constant returns to scale, canceling from both sides yields , where is the vacancy rate in period t. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | Further algebraic details can be found in Appendix B.1. |

| 9 | Further algebraic details can be found in Appendix C of the appendix. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | The derivation uses that fact that for some constant . |

| 12 | In Appendix D, I investigate increasing z, the flow value of nonwork. |

| 13 | |

| 14 | Chodorow-Reich (2014) documents these relationships around the Great Recession (see also Duygan-Bump et al., 2015; Montoriol-Garriga & Wang, 2011). Chodorow-Reich et al. (2022) provide evidence about US lending around COVID-19. Adam (2024) provides evidence on access to finance in Saudi Arabia.

|

| 15 | The choice of this parameter value has generated much interest. In particular, Hagedorn and Manovskii (2008) calibrated a worker’s value of nonwork to be around 95 percent of the wage, consistent with the idea that a marginal worker is indifferent between work and nonwork in traditional, non-matching models of the labor market. Under this calibration, the model can generate the observed cyclicality of labor-market tightness. Yet, the notion that there is little improvement in a worker’s welfare from transitioning from unemployment to employment may be hard to accept. There are other criticisms (Pissarides, 2009). Shimer (2005), Costain and Reiter (2008), and Ljungqvist and Sargent (2017) provide more context. |

References

- Adam, N. A. (2024). Perceived risk and external finance usage in small-and medium-sized enterprises: Unveiling the moderating influence of business age. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(4), 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnichon, R. (2010). Productivity and unemployment over the business cycle. Journal of Monetary Economics, 57(8), 1013–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügemann, B., & Moscarini, G. (2010). Rent rigidity, asymmetric information, and volatility bounds in labor markets. Review of Economic Dynamics, 13(3), 575–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chairassamee, N., Hean, O., & Jabas, P. (2023). The financial impact of state tax regimes on local economies in the U.S. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(10), 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodorow-Reich, G. (2014). The employment effects of credit market disruptions: Firm-level evidence from the 2008–2009 financial crisis. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodorow-Reich, G., Darmouni, O., Luck, S., & Plosser, M. (2022). Bank liquidity provision across the firm size distribution. Journal of Financial Economics, 144(3), 908–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiano, L. J., Eichenbaum, M. S., & Trabandt, M. (2021). Why is unemployment so countercyclical? Review of Economic Dynamics, 41, 4–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R. A., Ferris, K. R., & Melnik, A. L. (2016). The direct cost of advice in M&A transactions in the financial sector. SSRN, 1458465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costain, J. S., & Reiter, M. (2008). Business cycles, unemployment insurance, and the calibration of matching models. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 32(4), 1120–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, B., Geelen, T., & Green, B. (2024). Due diligence. The Journal of Finance, 79(3), 2115–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, P. (1982). Wage determination and efficiency in search equilibrium. The Review of Economic Studies, 49(2), 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, P. (1990). Pairwise credit in search equilibrium. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 105(2), 285–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duygan-Bump, B., Levkov, A., & Montoriol-Garriga, J. (2015). Financing constraints and unemployment: Evidence from the Great Recession. Journal of Monetary Economics, 75, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, E. (2019). Finance and jobs: How financial markets and prudential regulation shape unemployment dynamics. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 12(1), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyigungor, B. (2010). Specific capital and vintage effects on the dynamics of unemployment and vacancies. American Economic Review, 100(3), 1214–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garín, J., & Lester, R. (2019). The opportunity cost(s) of employment and search intensity. Macroeconomic Dynamics, 23(1), 216–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, M., & Trigari, A. (2009). Unemployment fluctuations with staggered nash wage bargaining. Journal of Political Economy, 117(1), 38–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomme, P., & Lkhagvasuren, D. (2015). Worker search effort as an amplification mechanism. Journal of Monetary Economics, 75, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., Ottonello, P., Winberry, T., & Whited, T. (2025). Firm heterogeneity and adverse selection in external finance: Micro evidence and macro implications. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedorn, M., & Manovskii, I. (2008). The cyclical behavior of equilibrium unemployment and vacancies revisited. American Economic Review, 98(4), 1692–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. E. (2005). Employment fluctuations with equilibrium wage stickiness. American Economic Review, 95(1), 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. E. (2011). The long slump. American Economic Review, 101(2), 431–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. E. (2017). High discounts and high unemployment. American Economic Review, 107(2), 305–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. E., & Milgrom, P. R. (2008). The limited influence of unemployment on the wage bargain. American Economic Review, 98(4), 1653–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, C. L. (2006). Adverse selection and the financial accelerator. Journal of Monetary Economics, 53(6), 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., Yu, H., & Zhang, Z. (2023). External vs. in-house advising service: Evidence from the financial industry acquisitions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(2), 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, K. L., Maliar, L., & Maliar, S. (2011). Numerically stable and accurate stochastic simulation approaches for solving dynamic economic models: Approaches for solving dynamic models. Quantitative Economics, 2(2), 173–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, P. J., Lopez, P., Midrigan, V., & Pastorino, E. (2023). Asset prices and unemployment fluctuations: A resolution of the unemployment volatility puzzle. The Review of Economic Studies, 90(3), 1304–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokonas, N. (2023). A note on the unemployment volatility puzzle. Oxford Economic Papers, 75(1), 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajoux, A. R., & Elson, C. M. (2011). The art of M&A (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Ljungqvist, L., & Sargent, T. J. (2017). The fundamental surplus. American Economic Review, 107(9), 2630–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungqvist, L., & Sargent, T. J. (2018). Recursive macroeconomic theory (4th ed.). The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ljungqvist, L., & Sargent, T. J. (2021). The fundamental surplus strikes again. Review of Economic Dynamics, 41, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliar, L., & Maliar, S. (2003). Parameterized expectations algorithm and the moving bounds. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 21(1), 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoriol-Garriga, J., & Wang, J. C. (2011). The great recession and bank lending to small businesses (Working Papers No. 11–16). Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/fip/fedbwp/11-16.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Mortensen, D. T. (1982). The matching process as a noncooperative bargaining (J. J. McCall, Ed.; pp. 233–258). University of Chicago Press. Available online: http://www.nber.org/books/mcca82-1 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Mortensen, D. T., & Nagypál, É. (2007). More on unemployment and vacancy fluctuations. Review of Economic Dynamics, 10(3), 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottonello, P., & Song, W. (2022). Financial intermediaries and the macroeconomy: Evidence from a high-frequency identification. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosky-Nadeau, N. (2014). Credit, vacancies and unemployment fluctuations. Review of Economic Dynamics, 17(2), 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosky-Nadeau, N., & Wasmer, E. (2013). The cyclical volatility of labor markets under frictional financial markets. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 5(1), 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Petrosky-Nadeau, N., & Wasmer, E. (2017). Labor, credit, and goods markets. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petrosky-Nadeau, N., & Zhang, L. (2017). Solving the diamond-mortensen-pissarides model accurately. Quantitative Economics, 8(2), 611–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pissarides, C. A. (1985). Short-run equilibrium dynamics of unemployment, vacancies, and real wages. The American Economic Review, 75(4), 676–690. [Google Scholar]

- Pissarides, C. A. (2000). Equilibrium unemployment theory (2nd ed.). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pissarides, C. A. (2009). The unemployment volatility puzzle: Is wage stickiness the answer. Econometrica, 77(5), 1339–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, R., & Shimer, R. (2011). Search in macroeconomic models of the labor market. In Handbook of labor economics (pp. 619–700). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, R., Shimer, R., & Wright, R. (2005). Search-theoretic models of the labor market: A survey. Journal of Economic Literature, 43(4), 959–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. (2023). Responses of unemployment to productivity changes for a general matching technolog. Economics Bulletin, 43(4), 1749–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. (2024). Unemployment volatility: When workers pay costs upon accepting jobs. International Journal of Economic Theory, 20, 303–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimer, R. (2005). The cyclical behavior of equilibrium unemployment and vacancies. American Economic Review, 95(1), 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimer, R. (2010). Labor markets and business cycles. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J. I., & Toledo, M. (2009). Labor turnover costs and the cyclical behavior of vacancies and unemployment. Macroeconomic Dynamics, 13(S1), 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J. I., & Toledo, M. (2013). The unemployment volatility puzzle: The role of matching costs revisited. Economic Inquiry, 51(1), 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J. C. (2003). Agency, Information and Corporate Investment. In Corporate finance (pp. 111–165). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. (2023). The fundamental surplus revisited. Review of Economic Dynamics, 51, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasmer, E., & Weil, P. (2004). The macroeconomics of labor and credit market imperfections. American Economic Review, 94(4), 944–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., & Lin, Z. (2025). The General Equilibrium Effects of Fiscal Policy with Government Debt Maturity. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(7), 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ryan, R. Credit-Market Cyclicality and Unemployment Volatility. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090477

Ryan R. Credit-Market Cyclicality and Unemployment Volatility. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(9):477. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090477

Chicago/Turabian StyleRyan, Rich. 2025. "Credit-Market Cyclicality and Unemployment Volatility" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 9: 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090477

APA StyleRyan, R. (2025). Credit-Market Cyclicality and Unemployment Volatility. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(9), 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090477