The Mediating Role of the Firm Image in the Relationship Between Integrated Reporting and Firm Value in GCC Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ 1: What is the impact of integrated reporting on firm value for companies listed on GCC stock exchanges?

- RQ 2: How does firm image mediate the relationship between integrated reporting and firm value for companies listed on GCC stock exchanges?

- RO 1: To examine how integrated reporting affects firm value for companies listed on GCC stock exchanges, taking into account all companies that regularly publish integrated reports.

- RO 2: To investigate the mediating function of the firm image in the relationship between integrated reporting and firm value for companies listed on GCC stock exchanges and to determine if firms with a better image encounter favourable effects on such a relationship.

2. Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Stakeholder Theory

2.2. Legitimacy Theory

2.3. Signalling Theory

3. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

3.1. Integrated Reporting and Firm Value

3.2. Mediating Role of Firm Image

4. Data and Methodology

4.1. Source of Data, Study Period, and Sample Size

4.2. Measurements of the Variables

4.2.1. Dependent Variable

4.2.2. Independent Variable

4.2.3. Mediating Variable

4.2.4. Control Variables

| Variable Name | Type | Measurement Method | Data Source |

| Firm Value (FV) | Dependent | Tobin’s Q | Company Reports |

| Integrated Reporting (IR) | Independent | Content analysis based on IIRF | Company Reports |

| Firm Image (FI) | Mediating | Binary proxy (award recognition) | Company Reports |

| Control Variables | Control | Firm size (log of assets), leverage, GDP | Company Reports and GDP from the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitive Reports |

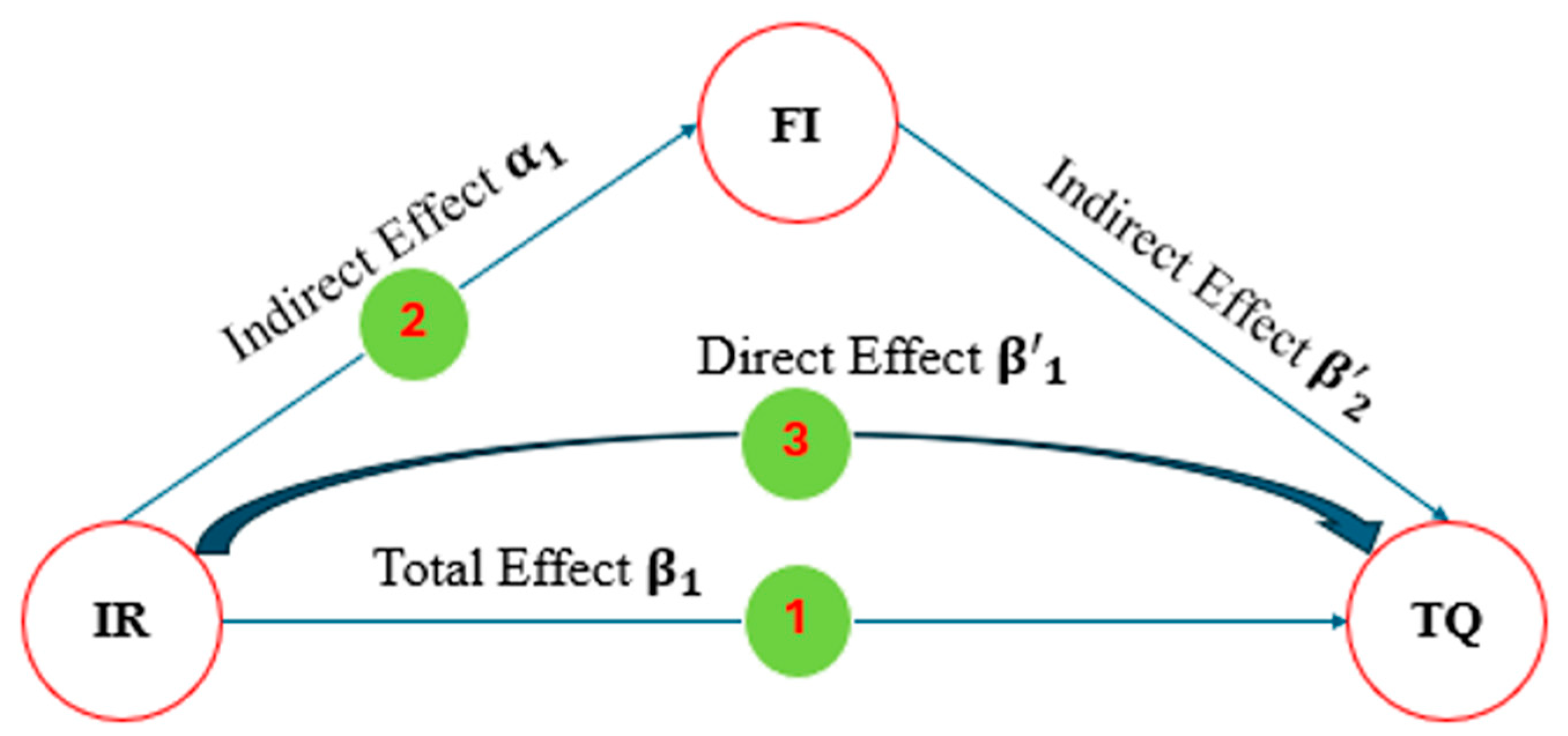

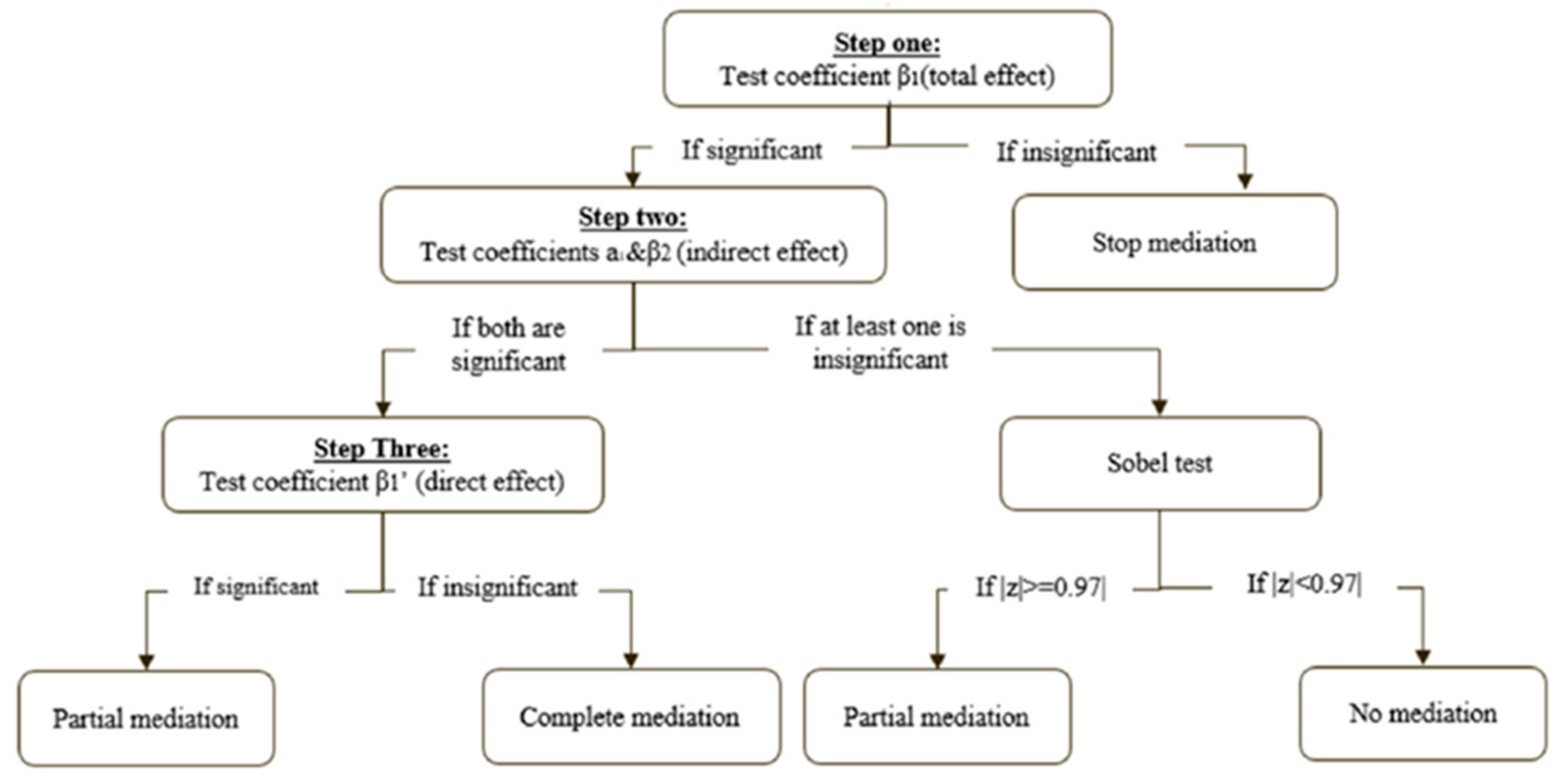

4.3. Empirical Model

5. Empirical Results and Discussion

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Correlation Matrix

5.3. Results and Discussion

5.3.1. Robustness Check

5.3.2. Implications of the Study

Theoretical Implication

Implications for Corporate Managers

Practical Implications for Policy Makers

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Disclosure Items |

|

| OE1 The nature of the organisation’s work and the circumstances in which it operates |

| OE2 Mission and vision of the organisation. |

| OE3 Culture, morals, and values. |

| OE4 Ownership and operating structure. |

| OE5 Competitive environment of the organisation. |

| OE6 The most important factors influencing the external environment |

| OE7 Needs of stakeholders. |

| OE8 Economic conditions in which the organisation operates. |

| OE9 Market forces. |

| OE10 Impact of technological changes. |

| OE11 Demographic and societal issues. |

| OE12 Environmental challenges faced by the organisation |

| OE13 The legislative and regulatory environment in which the organisation operates. |

| OE14 The political situation in the countries in which the organisation operates. |

|

| GO1 Disclose how the governance structure contributes to creating value for the organisation. |

| GO2 Disclose the characteristics of the organisation’s leadership structure. |

| GO3 The processes on which the organisation builds its strategic decisions and organisational culture. |

| GO4 Procedures for the impact and monitoring of strategic direction of the organisation. |

| GO5 The reflection of organisational culture, its values and ethics in its use and its impact on capital. |

| GO6 Promote and encourage innovation by governance officials. |

| GO7 Whether the organisation is implementing governance practices that exceed legal requirements |

| GO8 Relationship of wages and incentives provided to create value for the organisation. |

|

| BM1 A diagram showing the main elements of the organisation. |

| BM2 Identify the basic elements of the business model. |

| BM3 Show how the key inputs relate to the capitals on which the organisation depends. |

| BM4 Disclose inputs that contribute to creating value for the organisation. |

| BM5 The extent to which the organisation is distinguished in the market (e.g., product differentiation, market segmentation, marketing). |

| BM6 The degree of adoption of the business model on revenue generation. |

| BM7 The extent to which the business model adapts to changes. |

| BM8 Approach to innovation. |

| BM9 Organisation initiatives such as (staff training, process improvement). |

| BM10 Organisation outputs of products, services, and by-products such as waste and emission of gases. |

| BM11 Internal results such as organisational reputation, job loyalty, income, and cash flow. |

| BM12 External results such as (customer satisfaction, tax payment, brand loyalty, social and environmental impacts). |

| BM13 Positive results lead to maximising capital and creating value. |

| BM14 Negative results leading to capital reduction and lack of value. |

|

| RO1 Disclose the risks that affect the organisation’s ability to create value. |

| RO2 Sources of risk, whether internal or external. |

| RO3 Procedures taken to address the risks to which the organisation is exposed. |

|

| SR1 Strategic objectives of the organisation. |

| SR2 The organisation’s current strategies or intends to implement. |

| SR3 Resources allocated for the implementation of the strategy. |

| SR4 Measure achievements and goals. |

| SR5 Factors influencing the granting of a competitive advantage to the organisation (innovation, intellectual capital exploitation, evolution of the organisation and social and environmental considerations). |

|

| PE1 Quantitative indicators related to objectives, opportunities and risks. |

| PE2 The positive and negative effects of the organisation on capital. |

| PE3 Organisation’s response to stakeholder needs. |

| PE4 Linking previous and current performance. |

| PE5 Key performance indicators that combine financial measures and other components. |

|

| OL1 Outlook of the organisation about the external environment. |

| OL2 Impact of the external environment on the organisation. |

| OL3 Organisation’s preparedness to respond to challenges that could occur. |

| OL4 The impact of the external environment, risks and opportunities on achieving the organisation’s strategic objectives. |

| OL5 The availability of financial and natural resources that support the institution’s ability to create value in the future. |

| OL6 Disclosure of the organisation’s expectations in accordance with regulatory or legal requirements. |

|

| BP1 Summary of the process of determining the material importance of the organisation (such as determining the role of those responsible for governance and staff who prioritize of material matters). |

| BP2 A description of the reporting boundary and how it has been determined. |

| BP3 Summary of the significant frameworks and methods used to quantify or evaluate material matters included in the report (e.g., the applicable financial reporting standards used for compiling financial information, a company-defined formula for measuring customer satisfaction, or an industry-based framework for evaluating risks). |

References

- Ahmed, A. H., Elmaghrabi, M. E., Dunne, T., & Hussainey, K. (2021). Gaining momentum: Towards integrated reporting practices in Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Business Strategy and Development, 4, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amosh, H., Khatib, S. F. A., & Hussainey, K. (2022). The financial determinants of integrated reporting disclosure by Jordanian companies. Journal of Risk & Financial Management, 15(9), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E. M., Bohon, L. M., & Berrigan, L. P. (1996). Factor structure of the private self-consciousness scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguelles, L., Balatbat, M. C., & Green, W. (2015). Is there an association between integrated reporting and the cost of equity capital? Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 26(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M. E., Cahan, S. F., Chen, L., & Venter, E. R. (2017). The economic consequences associated with integrated report quality: Capital market and real effects. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 62, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, G. C., & Saudagaran, S. M. (1991). Foreign stock listings: Benefits, costs, and the accounting policy dilemma. Accounting Horizons, 5(3), 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bijlmakers, L. (2018). The influence of integrated reporting on firm value. Master of Science in Business Economics, University of Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, S. R. (2002). Dynamic panel data models: A guide to micro data methods and practice. Portuguese Economic Journal, 1, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breusch, T. S., & Pagan, A. R. (1980). The Lagrange Multiplier Test and its Applications to Model Specification in Econometrics. The Review of Economic Studies, 47(1), 239--253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A. (2019). Is sustainability reporting (ESG) associated with performance? Evidence from the European banking sector. Management of Environmental Quality, 30(1), 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buys, P., Bosman, P., & Gloeck, J. D. (2009). The impact of IFRS on equity: The South African experience. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 7(10), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, L. (2012). Reputation on the internet. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cahan, S. F., De Villiers, C., Jeter, D. C., Naiker, V., & Van Staden, C. J. (2015). Are CSR disclosures value relevant? Cross-country Evidence. European Accounting Review, 25(3), 579–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmelarova, V., & Hill, R. C. (2010). The Hausman pretest estimator. Economics Letters, 108(1), 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosma, S., Soana, M. G., & Venturelli, A. (2018). Does the market reward integrated report quality? African Journal of Business Management, 12(4), 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- De Klerk, M., & de Villiers, C. (2012). The value relevance of corporate responsibility reporting: South African evidence. Meditari Accountancy Research, 20(1), 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C., & Gordon, B. (1996). A study of the environmental disclosure practices of australian corporations. Accounting and Business Research, 26, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P. K. (2020). Integrated reporting and market valuation: Evidence from the banking industry. Asian Journal of Accounting Research, 5(1), 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Falatifah, E. W., & Hermawan, A. (2021). Board of directors effectiveness, voluntary integrated reporting and cost of equity: Evidence from OECD countries. International Journal of Business and Society, 22(1), 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C. J. (2005). A world of reputation research, analysis and thinking—Building corporate reputation through CSR initiatives: Evolving standards. Corporate Reputation Review, 8, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman. [Google Scholar]

- Galbreath, J., & Shum, P. (2012). Do customer satisfaction and reputation mediate the CSR–FP link? Evidence from Australia. Australian Journal of Management, 37(2), 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D., & Mallery, M. (2010). SPSS for windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Gerwanski, J. (2020). Does it pay off? Integrated reporting and cost of debt: European evidence. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27, 2299–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgino, M. C., Supino, E., & Barnabè, F. (2017). Corporate disclosure, materiality, and integrated report: An event study analysis. Sustainability, 9(12), 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (2003). Basic econometrics. McGrew Hill Book Co. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J., & Parker, L. (1990). Corporate social disclosure practice: A comparative international analysis. Advances in Public Interest Accounting, 3, 159–175. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J., Petty, R., Yongvanich, K., & Ricceri, F. (2004). Using content analysis as a research method to inquire into intellectual capital reporting. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 5(2), 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, F. (2017). The effects of board characteristics and sustainable compensation policy on carbon performance of UK firms. The British Accounting Review, 49(3), 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification Tests in Econometrics. Econometrica, 46(6), 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IIRC. (2018). Technical programme: Progress report. Available online: https://integratedreporting.ifrs.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Final_Online-Progress-Report.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Iyoha, F. O., Ojeka, S. A., & Ogundana, O. M. (2017). Bankers’ perspectives on integrated reporting for value creation. Banks and Bank Systems, 12(4), 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassai, J. R., & Carvalho, N. (2016). Integrated reporting: When, why and how did it happen? In C. Mio (Ed.), Integrated reporting. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG. (2020). The time has come: The KPMG survey of sustainability reporting 2020. KPMG International. Available online: https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2020/11/the-time-has-come-survey-of-sustainability-reporting.html (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, C. S., Chiu, C. J., Yang, C. F., & Pai, D. C. (2010). The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand performance: The mediating effect of industrial brand equity and corporate reputation. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(3), 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. W., & Yeo, G. H. H. (2016). The association between integrated reporting and firm valuation. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 47(4), 1221–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, E. G., Lim, J., & Bednar, M. K. (2017). The face of the firm: The influence of CEOs on corporate reputation. Academy of Management Journal, 60(4), 1213–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmendier, U., & Tate, G. (2009). Superstar CEOs. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(4), 1593–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroun, W. (2017). Assuring the integrated report: Insights and recommendations from auditors and preparers. The British Accounting Review, 49(3), 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttakin, M. B., Mihret, D., Lemma, T. T., & Khan, A. (2020). Integrated reporting, financial reporting quality and cost of debt. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 28(3), 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhili, M., Nagati, H., Chtioui, T., & Rebolledo, C. (2017). Corporate social responsibility disclosure and market value: Family versus nonfamily firms. Journal of Business Research, 77, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Permatasari, I., & Narsa, I. M. (2022). Sustainability reporting or integrated reporting: Which one is valuable for investors? Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 18(5), 666–684. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, H., & Tran, Q. (2020). CSR disclosure and firm performance: The mediating role of corporate reputation and moderating role of CEO integrity. Journal of Business Research, 120, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar]

- Rindova, V. P., Williamson, I. O., Petkova, A. P., & Sever, J. M. (2005). Being good or being known: An empirical examination of the dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of organizational reputation. Academy of Management Journal, 48(6), 1033–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P. W., & Dowling, G. R. (2002). Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 23(12), 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do Xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in stata. The Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S. P., Sofian, S., Saeidi, P., Saeidi, S. P., & Saaeidi, S. A. (2015). How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Business Research, 68(2), 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, M. E. (1986). Some new results on indirect effects and their standard errors in covariance structure models. Sociological Methodology, 16, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumillion, V. (2018). The value relevance of integrated reporting in South Africa. Master of Science in Business Economics, University Gent. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unerman, J. (2000). Methodological issues—Reflections on quantification in corporate social reporting content analysis. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 13, 667–681. [Google Scholar]

- Velte, P. (2022). Archival research on integrated reporting: A systematic review of main drivers and the impact of integrated reporting on firm value. Journal of Management & Governance, 26(3), 997–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Vitolla, F., Raimo, N., & Rubino, M. (2020). Board characteristics and integrated reporting quality: An agency theory perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(2), 1152–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, J. B., Porac, J. F., Pollock, T. G., & Graffin, S. D. (2006). The burden of celebrity: The impact of CEO certification contests on CEO pay and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, A., Charifzadeh, M., & Diefenbach, F. (2019). Voluntary adopters of integrated reporting–evidence on forecast accuracy and firm value. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(5), 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M., Peng, F., Shan, Y. G., & Zhang, L. (2020). Litigation risk and firm performance: The effect of internal and external corporate governance. Corporate Governance: An International Journal, 28(4), 210–239. [Google Scholar]

- Zeghal, D., & Ahmed, S. A. (1990). Comparison of social responsibility information disclosure media used by Canadian firms. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 3(1), 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S., Simnett, R., & Green, W. (2017). Does integrated reporting matter to the capital market? Abacus, 53(1), 94–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Min. | Max. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Skew. | Kurto. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR | 0.090 | 0.900 | 0.485 | 0.161 | 0.156 | −0.940 |

| DE | 0.000 | 5.000 | 0.578 | 0.791 | 0.897 | 1.257 |

| FS | 0.460 | 13.390 | 6.915 | 2.112 | 0.508 | 0.170 |

| GDP | 3.540 | 7.010 | 5.506 | 1.002 | −0.178 | −1.079 |

| IND | 0.032 | 0.425 | 0.333 | 0.077 | 0.093 | 1.896 |

| GD | 0.000 | 28.570 | 7.998 | 2.284 | 0.390 | 0.213 |

| FI | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.350 | 0.479 | 0.607 | −1.635 |

| TQ | 0.010 | 18.780 | 1.530 | 2.446 | 1.062 | 1.993 |

| Variables | VIF | IR | DE | TQ | FS | GDP | IND | GD | FI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR | 1.13 | 1 | |||||||

| DE | 1.2 | 0.16 ** | 1 | ||||||

| TQ | 0.11 | 0.01 | −0.07 | 1 | |||||

| FS | 3.56 | 0.01 | 0.26 ** | 0.21 ** | 1 | ||||

| GDP | 1.59 | 0.02 | 0.08 ** | 0.13 | 0.26 ** | 1 | |||

| IND | 1.21 | 0.01 | −0.08 ** | 0.01 | −0.06 * | 0.19 ** | 1 | ||

| GD | 1.17 | 0.062 * | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.09 ** | −0.05 | 0.25 ** | 1 | |

| FI | 3.24 | 0.06 | 0.08 * | 0 | 0.08 * | 0.15 ** | 0.05 | −0.10 ** | 1 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

| Dependent Variable: (TQ) | Dependent Variable: (FI) | Dependent Variable: (TQ) | |||||||

| Coeff. | Std. Error | Z-Stats. | Coeff. | Std. Error | Z-Stats. | Coeff. | Std. Error | Z-Stats. | |

| Const. | 7.526 | 2.065 | 3.644 *** | −0.844 | 0.304 | −2.780 *** | 9.354 | 0.925 | 10.113 *** |

| FI | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.212 [β′2] | 0.103 | 2.058 ** |

| IR | 1.321 [β1] | 0.529 | 2.496 ** | 0.215 [α1] | 0.130 | 1.660 * | 1.220 [β′1] | 0.371 | 3.288 *** |

| FS | 1.004 | 0.302 | 3.324 *** | 0.042 | 0.024 | 1.710 * | 1.174 | 0.104 | 11.300 *** |

| DE | −0.135 | 0.138 | −0.983 | 0.038 | 0.065 | 0.580 | −0.135 | 0.092 | −1.471 |

| IND | 1.205 | 1.576 | 0.765 | 1.609 | 0.660 | 2.440 ** | 1.772 | 1.437 | 1.233 |

| GD | 0.023 | 0.046 | 0.490 | −0.011 | 0.010 | −1.110 | 0.047 | 0.039 | 1.205 |

| GDP | 0.063 | 0.053 | 1.182 | 0.069 | 0.061 | 1.130 | 0.484 | 0.314 | 1.540 |

| Lag_TQ | 0.276 | 0.092 | 2.997 *** | - | - | - | 0.276 | 0.092 | 2.997 *** |

| Lag_FI | - | - | - | −0.058 | 0.037 | −1.570 | - | - | - |

| Sargan test: (p-value) | 0.234 | 0.338 | 0.213 | ||||||

| Hansen test: (p-value) | 0.111 | 0.154 | 0.220 | ||||||

| AR (1): | 0.130 | 0.187 | 0.120 | ||||||

| AR (2): | 0.195 | 0.139 | 0.264 | ||||||

| Wald (ϰ2) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Mediation Effect based on the Outcome of Models 1, 2 and 3 | |||||||||

| Coefficients are significant | β1 = 1.321 **; α1 = 0.215 *; β′2 = 0.212 **; β′1 = 1.220 *** | ||||||||

| Sobel test | No Sobel test is required. | ||||||||

| Mediation Effect | Partial | ||||||||

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

| Dependent Variable: (TQ) | Dependent Variable: (FI) | Dependent Variable: (TQ) | |||||||

| Coeff. | Robust Std. Error | Z-Stats. | Coeff. | Std. Error | Z-Stats. | Coeff. | Robust Std. Error | Z-Stats. | |

| Const. | −0.379 | 0.225 | −1.686 * | −0.160 | 0.235 | −0.681 | 0.334 | 0.225 | 1.486 |

| FI | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.050 [β′2] | 0.020 | 2.520 ** |

| IR | 0.757 [β1] | 0.106 | 7.155 *** | 0.492 [α1] | 0.101 | 4.89 *** | 0.463 [β′1] | 0.084 | 5.500 *** |

| FS | 0.117 | 0.031 | 3.769 *** | 0.021 | 0.009 | 2.431 ** | 0.173 | 0.037 | 4.675 *** |

| DE | 0.019 | 0.028 | 0.675 | 0.075 | 0.051 | 1.470 | 0.119 | 0.078 | 1.525 |

| IND | 0.083 | 0.283 | 0.295 | 0.460 | 0.447 | 1.031 | 0.100 | 0.260 | 0.387 |

| GD | 0.021 | 0.009 | 2.432 ** | −0.013 | 0.011 | −1.169 | 0.024 | 0.009 | 2.538 ** |

| GDP | 0.161 | 0.115 | 1.395 | 0.133 | 0.092 | 1.446 | 0.067 | 0.049 | 1.367 |

| Lag_TQ | 0.351 | 0.110 | 3.190 *** | - | - | - | 0.351 | 0.069 | 5.076 *** |

| Lag_FI | - | - | - | 0.064 | 0.049 | 1.306 | - | - | - |

| R2 Overall | 0.250 | 0.1630 | 0.254 | ||||||

| F-stats. | 16.74 *** | 22.788 *** | 24.765 *** | ||||||

| B-P test (ϰ2) | 203.967 *** | 186.78 *** | 198.324 *** | ||||||

| Hausman test (ϰ2) | 131.728 *** | 148.559 *** | 138.226 *** | ||||||

| DWH test of endogeneity: | |||||||||

| Durbin (ϰ2) | 1.762 (p = 0.172) | 1.567 (p = 0.2153) | 1.546 (p = 0.1257) | ||||||

| Wu-Hausman (F-stats.) | 1.812 (p = 0.1821) | 2.814 (p = 0.1484) | 1.683 (p = 0.1345) | ||||||

| Mediation effect based on the outcome of Models 1, 2 and 3 | |||||||||

| Coefficients are significant | β1 = 0.757 ***; α1 = 0.492 ***; β′2 = 0.050 **; β′1 = 0.463 *** | ||||||||

| Sobel test | No Sobel test is required. | ||||||||

| Mediation effect | Partial | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alatawi, M.S.; Daud, Z.M.; Johari, J. The Mediating Role of the Firm Image in the Relationship Between Integrated Reporting and Firm Value in GCC Countries. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 438. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080438

Alatawi MS, Daud ZM, Johari J. The Mediating Role of the Firm Image in the Relationship Between Integrated Reporting and Firm Value in GCC Countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(8):438. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080438

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlatawi, Mohammed Saleem, Zaidi Mat Daud, and Jalila Johari. 2025. "The Mediating Role of the Firm Image in the Relationship Between Integrated Reporting and Firm Value in GCC Countries" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 8: 438. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080438

APA StyleAlatawi, M. S., Daud, Z. M., & Johari, J. (2025). The Mediating Role of the Firm Image in the Relationship Between Integrated Reporting and Firm Value in GCC Countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(8), 438. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18080438