What Drives Cost System Sophistication? Empirical Evidence from the Greek Hotel Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cost Structure in the Hospitality Industry and Implications for Cost System Design

2.2. Advancing Cost System Design

2.3. Contingency and Upper Echelons Theories in Cost System Design Research

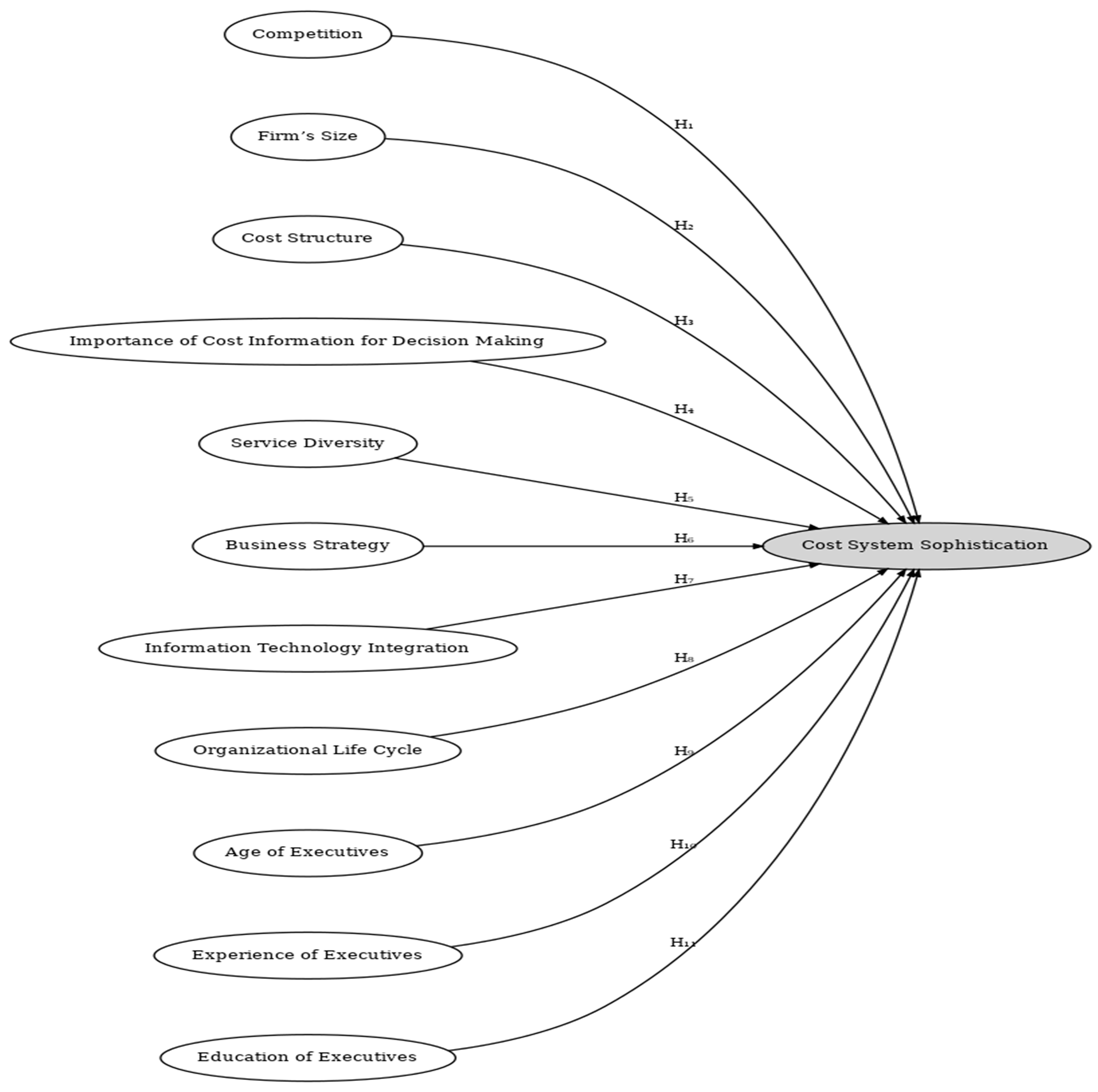

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Competition

3.2. Firm’s Size

3.3. Cost Structure

3.4. Importance of Cost Information for Decision-Making

3.5. Service Diversity

3.6. Business Strategy

3.7. Information Technology Integration

3.8. Organizational Life Cycle

3.9. Characteristics of Executives

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Sample and Data Collection

4.2. Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

4.3. Measurement of Variables

4.4. Data Analysis Techniques

5. Analysis and Results

5.1. Validity and Reliability Analysis

5.2. Correlations

5.3. Regression Results

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abernethy, M. A., Lillis, A. M., Brownell, P., & Carter, P. (2001). Product diversity and costing system design choice: Field study evidence. Management Accounting Research, 12(3), 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. M., & Elmassri, M. (2025). The management accounting system design in family firms: The role of leadership and entrepreneurial orientation. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. Ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, N., & Albu, C. N. (2012). Factors associated with the adoption and use of management accounting techniques in developing countries: The case of Romania. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 23(3), 245–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulou, S., Balios, D., & Kounadeas, T. (2024). Essential factors when designing a cost accounting system in Greek manufacturing entities. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(8), 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omiri, M., & Drury, C. (2007). A survey of factors influencing the choice of product costing systems in UK organizations. Management Accounting Research, 18(4), 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharari, N. M., Alomari, A., & Alnesafi, A. (2020). Costs allocation practices and operations management in the hotels’ industry: Evidence from UAE. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity, and Change, 14(5), 512–545. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarany, D., & Yazdifar, H. (2012). An investigation into the mixed reported adoption rates for ABC: Evidence from Australia, New Zealand and the UK. International Journal of Production Economics, 135(1), 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarany, D., Yazdifar, H., & Askary, S. (2010). Supply chain management, activity-based costing and organisational factors. International Journal of Production Economics, 127(2), 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auzair, S. M., & Langfield-Smith, K. (2005). The effect of service process type, business strategy and life cycle stage on bureaucratic MCS in service organizations. Management Accounting Research, 16(4), 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, A., & Langfield-Smith, K. (2003). Antecedents to management accounting change: A structural equation approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(7–8), 675–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banhmeid, B., & Aljabr, A. (2023). The relationship between the role of management accountants, advanced manufacturing technologies, cost system sophistication and performance: A path model. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. Ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R. D., & Johnston, H. H. (2006). Cost and profit driver research. Handbooks of Management Accounting Research, 2, 531–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, D., Brown, D. A., Malmi, T., & Sivabalan, P. (2008). Balanced Scorecard design and performance impacts: Some Australian evidence. Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research, 6(2), 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Beheshti, H. M. (2004). Gaining and sustaining competitive advantage with activity-based cost management systems. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 104(5), 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berisha, V., & Miftari, I. (2022). CFO and CEO characteristics and managerial accounting techniques (MAT’s) usage. Journal of East European Management Studies, 27(2), 348–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnenak, T. (1997). Diffusion and accounting: The case of ABC in Norway. Management Accounting Research, 8(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, L. H., & Cox, J. F. (2002). Optimal decision-making using cost accounting information. International Journal of Production Research, 40(8), 1879–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, J. A. (2008). Toward an understanding of the sophistication of product costing systems. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 20, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, J. A. (2010). The determinants of overhead assignment sophistication in product costing systems. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 21(4), 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, J. A., Cowton, C. J., & Drury, C. (2001). Research into product costing practice: A European perspective. European Accounting Review, 10(2), 215–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brignall, S. (1997). A contingent rationale for cost system design in services. Management Accounting Research, 8(3), 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brignall, T. J., Fitzgerald, L., Johnston, R., & Silvestro, R. (1991). Product costing in service organizations. Management Accounting Research, 2(4), 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. L., & Kros, J. F. (2003). Data mining and the impact of missing data. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 103(8), 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadez, S., & Guilding, C. (2008). An exploratory investigation of an integrated contingency model of strategic management accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(7–8), 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, C. M., & Gabriel, E. A. (1998). The differential impact of accurate product cost information in imperfectly competitive markets: A theoretical and empirical investigation. Contemporary Accounting Research, 15(4), 419–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón, C. (2000). Strategic attitudes and information technologies in the hospitality business: An empirical analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 19(2), 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoni, A., Paradisi, A., & Hiebl, M. (2023). Management accounting implementation in SMEs: A structured literature review. Management Control, 2, 189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzis, A., Thanasas, G. L., & Koulidou, A. (2023). Exploring the relationship between industry characteristics and the adoption of an innovative cost accounting method: A literature review on the greek context. Theoretical Economics Letters, 13(6), 1608–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Firth, M., & Park, K. (2001). The implementation and benefits of activity-based costing: A Hong Kong study. Asian Review of Accounting, 9(2), 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenhall, R. H. (2003). Management control systems design within its organizational context: Findings from contingency-based research and directions for the future. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28, 127–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenhall, R. H., & Langfield-Smith, K. (1998). Adoption and benefits of management accounting practices: An Australian study. Management Accounting Research, 9(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenhall, R. H., & Langfield-Smith, K. (1999). The implementation of innovative management accounting systems. Australian Accounting Review, 9(3), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, Y. M., & Koh, H. C. (2007). Organizational culture and the adoption of management accounting practices in the public sector: A Singapore study. Financial Accountability & Management, 23(2), 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chishamba, J. (2024). Conceptualizing strategic leadership: Theories, themes, and varying perspectives. Œconomica, 20(5), 49–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cinquini, L., Collini, P., Marelli, A., & Tenucci, A. (2015). Change in the relevance of cost information and costing systems: Evidence from two Italian surveys. Journal of Management & Governance, 19(3), 557–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinquini, L., & Tenucci, A. (2010). Strategic management accounting and business strategy: A loose coupling? Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 6(2), 228–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claver-Cortés, E., Molina-Azorín, J. F., & Pereira-Moliner, J. (2007). The impact of strategic behaviours on hotel performance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 19(1), 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., & Kaimenaki, E. (2011). Cost accounting systems structure and information quality properties: An empirical analysis. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 12(1), 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D. R., & Schindler, P. (2003). Business research methods (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill Irwin. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, R. (1988). The rise of ABC—Part two: When do I need an ABC system? Journal of Cost Management, 1(1), 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Daowadueng, P., Hoozée, S., Jorissen, A., & Maussen, S. (2023). Do costing system design choices mediate the link between strategic orientation and cost information usage for decision-making and control? Management Accounting Research, 61, 100854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diavastis, I., Anagnostopoulou, E., Drogalas, G., & Karagiorgos, T. (2016). The interaction effect of accounting information systems user satisfaction and activity-based costing use on hotel financial performance: Evidence from Greece. Journal of Accounting and Management Information Systems, 15(4), 757–784. [Google Scholar]

- Dittman, D. A., Hesford, J. W., & Potter, G. (2009). Managerial accounting in the hospitality industry. Handbook of Management Accounting Research, 3, 1353–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, H. R., Fullerton, S., & Robbins, J. E. (1994). Stage of the organizational life cycle and competition as mediators of problem perception for small businesses. Strategic Management Journal, 15(2), 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazin, R., & Van de Ven, A. H. (1985). Alternative forms of fit in contingency theory. Administrative Science Quarterly, 30(4), 514–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, C., & Tayles, M. (2005). Explicating the design of overhead absorption procedures in UK organizations. British Accounting Review, 37(1), 47–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, C., & Tayles, M. (2006). Profitability analysis in UK organizations: An exploratory study. British Accounting Review, 38(4), 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunk, A. S. (2001). Behavioral research in management accounting: The past, present, and future. In J. E. Hunton (Ed.), Advances in accounting behavioral research (pp. 25–45). Emerald. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enz, C. A., & Potter, G. (1998). The impacts of variety on the costs and profits of a hotel chain’s properties. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 22(2), 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J. G., & Krumwiede, K. (2015). Product costing systems: Finding the right approach. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 26(4), 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foong, S. Y., & Anak Teruki, N. (2009). Cost-system functionality and the performance of the Malaysian palm oil industry. Asian Review of Accounting, 17(3), 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox-Wasylyshyn, S. M., & El-Masri, M. M. (2005). Handling missing data in self-report measures. Research in Nursing & Health, 28(6), 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdin, J. (2005). Management accounting system design in manufacturing departments: An empirical investigation using a multiple contingencies approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 30(1), 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdin, J., & Greve, J. (2004). Forms of contingency fit in management accounting research—A critical review. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(3–4), 303–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajan, V. (1989). Implementing competitive strategies at the business unit level: Implications of matching managers to strategies. Strategic Management Journal, 10(3), 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, L. E. (1972). Evolution and revolution as organizations grow. Harvard Business Review, 76(3), 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Guilding, C., Kennedy, D. J., & McManus, L. (2001). Extending the boundaries of customer accounting: Applications in the hotel industry. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 25(2), 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurses, A. P. (1999). An activity-based costing and theory of constraints model for product-mix decisions [Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Hadid, W., & Hamdan, M. (2022). Firm size and cost system sophistication: The role of firm age. British Accounting Review, 54(2), 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Haldma, T., & Lääts, K. (2002). Contingencies influencing the management accounting practices of Estonian manufacturing companies. Management Accounting Research, 13(4), 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D. C. (2016). Upper echelons theory. In The Palgrave encyclopedia of strategic management. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiamey, S. E., & Amenumey, E. K. (2013). Exploring service outsourcing in 3–5 Star hotels in the Accra Metropolis of Ghana. Tourism Management Perspectives, 8, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebl, M. R. (2014). Upper echelons theory in management accounting and control research. Journal of Management Control, 24, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebl, M. R., Gärtner, B., & Duller, C. (2017). Chief financial officer (CFO) characteristics and ERP system adoption: An upper-echelons perspective. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 13(1), 85–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Z. (2004). A contingency model of the association between strategy, environmental uncertainty and performance measurement: Impact on organizational performance. International Business Review, 13(4), 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S. B., & Paulson Gjerde, K. A. (2003). Do different cost systems make a difference? Management Accounting Quarterly, 5(1), 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Humeedat, M. M. (2020). New environmental factors affecting cost systems design after COVID-19. Management Science Letters 10, 3777–3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M. M., & Gunasekaran, A. (2001). Activity-based cost management in financial services industry. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 11(3), 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S. M., Sibai, I. M. E., & Din, B. B. E. (2021). Contextualizing cost system design: A literature review. Journal of Accounting and Management Information Systems, 20(1), 28–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, T. H., & Mahmoud, N. (2012). The influence of organizational and environmental factors on cost systems design in Egypt. British Journal of Economics, Finance and Management Sciences, 4(2), 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Jänkälä, S., & Silvola, H. (2012). Lagging effects of the use of activity-based costing on the financial performance of small firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 50(3), 498–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermias, J. (2008). The relative influence of competitive intensity and business strategy on the relationship between financial leverage and performance. The British Accounting Review, 40(1), 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P., & Lockwood, A. (2002). The management of hotel operations. Cengage Learning EMEA. [Google Scholar]

- Kallunki, J. P., & Silvola, H. (2008). The effect of organizational life cycle stage on the use of activity-based costing. Management Accounting Research, 19(1), 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. S. (1988). One cost system isn’t enough (pp. 61–66). Harvard Business Review. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R. S., & Cooper, R. (1998). Cost and effect: Using integrated systems to drive profitability and performance. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khandwalla, P. N. (1972). The effect of different types of competition on the use of management controls. Journal of Accounting Research, 10, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R., Clarkson, P. M., & Wallace, S. (2010). Budgeting practices and performance in small healthcare businesses. Management Accounting Research, 21(1), 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klink, J., & Budding, T. (2025). Antecedents and use of cost accounting systems in Dutch executive agencies. Public Money & Management, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotas, R. (1999). Management accounting for hospitality and tourism (3rd ed.). International Thomson Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krumwiede, K. R. (1998). The implementation stages of activity-based costing and the impact of contextual and organizational factors. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 10, 239–277. [Google Scholar]

- Krumwiede, K. R., Suessmair, A., & MacDonald, J. (2014). A framework for measuring the complexity of cost systems. AAA 2014 Management Accounting Section (MAS) Meeting Paper. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2311720 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Kuzey, C., Uyar, A., & Delen, D. (2019). An investigation of the factors influencing cost system functionality using decision trees, support vector machines and logistic regression. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 27(1), 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamminmaki, D. (2008). Accounting and the management of outsourcing: An empirical study in the hotel industry. Management Accounting Research, 19(2), 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y. (2002). An examination of international differences in adoption and theory development of activity-based costing. Advances in International Accounting, 15, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, V. L., & Churchill, N. C. (1983). The five stages of small business growth. Harvard Business Review, 61(3), 30–50. [Google Scholar]

- Liem, V. T. (2021). The impact of education background on using cost management system information. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1944011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M., & Rafferty, J. (2008). Cost analysis for pricing: Exploring the gap between theory and practice. The British Accounting Review, 40(2), 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiga, A. S. (2015). Information systems integration and firm profitability: Mediating effect of cost management strategy. In M. Epstein, & J. Lee (Eds.), Advances in management accounting (pp. 149–179). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiga, A. S. (2017). Assessing the main and interaction effects of activity-based costing and internal and external information systems integration on manufacturing plant operational performance. In M. Malina (Ed.), Advances in management accounting (pp. 55–90). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiga, A. S., Nilsson, A., & Jacobs, F. A. (2014). Assessing the interaction effect of cost control systems and information technology integration on manufacturing plant financial performance. The British Accounting Review, 46(1), 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmi, T. (1999). Activity-based costing diffusion across organizations: An exploratory empirical analysis of Finnish firms. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 24(8), 649–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazbayeva, K., Barysheva, S., & Saparbayeva, S. S. (2021). The influence of the importance of cost information, product diversity and accountants’ participation on the activity-based costing adoption. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 18(2), 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellahi, K., & Harris, L. C. (2016). Response rates in business and management research: An overview of current practice and suggestions for future direction. British Journal of Management, 27(2), 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D., & Friesen, P. H. (1983). Successful and unsuccessful phases of the corporate life cycle. Organization Studies, 4(4), 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D., & Friesen, P. H. (1984). A longitudinal study of the corporate life cycle. Management Science, 30(10), 1161–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moores, K., & Yuen, S. (2001). Management accounting systems and organizational configuration: A life-cycle perspective. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 26(4–5), 351–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M., & Lecci, F. (2014). Management control systems (MCS) change and the impact of top management characteristics: The case of healthcare organisations. Journal of Management Control, 24(3), 267–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najera Ruiz, T., & Collazzo, P. (2021). Determinants of the use of accounting systems in microenterprises: Evidence from Chile. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 11(4), 632–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Gil, D., & Hartmann, F. (2007). Management accounting systems, top management team heterogeneity and strategic change. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(7–8), 735–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Gil, D., Maas, V. S., & Hartmann, F. G. (2009). How CFOs determine management accounting innovation: An examination of direct and indirect effects. European Accounting Review, 18(4), 667–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, M., Morris, D., Thomas, A., & Sangster, A. (2009). An empirical study of activity-based costing (ABC) systems within the Jordanian industrial sector: Critical success factors and barriers to ABC implementation. In M. Tsamenyi, & S. Uddin (Eds.), Accounting in emerging economies (pp. 229–263). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otley, D. T. (1980). The contingency theory of management accounting: Achievement and prognosis. In C. Emmanuel, D. Otley, & K. Merchant (Eds.), Readings in accounting for management control (pp. 83–106). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiar, A. (2016). Costs allocation practices: Evidence of hotels in Australia. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatos, O. (2010). The impact of firm characteristics on ABC systems: A Greek-based empirical analysis. In M. Epstein, J.-F. Manzoni, & A. Davila (Eds.), Performance measurement and management control: Innovative concepts and practices (pp. 501–527). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatos, O. (2011). The impact of strategic management accounting and cost structure on ABC systems in hotels. The Journal of Hospitality Financial Management, 19(2), 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatos, O. (2012). The impact of CFOs’ characteristics and information technology on cost management systems. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 13(3), 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatos, O., & Ioakimidis, M. (2024). Management accountants with a growth mindset and changes in the design of costing systems: The role of organisational culture. Accounting & Finance, 64(2), 2085–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatos, O., & Kostakis, H. (2018). Management accounting innovations in a time of economic crisis. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 18, e00106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatos, O., & Kostakis, H. (2022). Exploring the relationship between target costing functionality and product innovation: The role of information systems. Australian Accounting Review, 32(1), 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatos, O., & Paggios, I. (2007). Cost accounting in Greek hotel enterprises: An empirical approach. Tourismos: An International Multidisciplinary Journal of Tourism, 2(2), 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlatos, O., & Paggios, I. (2009). A survey of factors influencing the cost system design in hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(2), 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzini, M. J. (2006). The relation between cost-system design, managers’ evaluations of the relevance and usefulness of cost data, and financial performance: An empirical study of US hospitals. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(2), 179–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ratnatunga, J., Michael, S. C., & Balachandran, K. R. (2012). Cost management in Sri Lanka: A case study on volume, activity and time as cost drivers. The International Journal of Accounting, 47(3), 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J. M. (1996). Projects, models, and systems—Where is ABM headed? Journal of Cost Management, 10, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Reheul, A. M., & Jorissen, A. (2014). Do management control systems in SMEs reflect CEO demographics? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 21(3), 470–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffia, P., Benavides, M. M., & Carrilero, A. (2024). Cost accounting practices in SMEs: Liability of age and other factors that hinder or burst its implementation in turbulent years. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 20(1), 115–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartorius, K., Eitzen, C., & Kamala, P. (2007). The design and implementation of activity based costing (ABC): A South African survey. Meditari Accountancy Research, 15(2), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2012). Research methods for business students. Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer, J. D. (1986). Structure and strategy: Two sides of success. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 26(4), 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlissel, M. R., & Chasin, J. (1991). Pricing of services: An interdisciplinary review. Service Industries Journal, 11(3), 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoute, M. (2009). The relationship between cost system complexity, purposes of use, and cost system effectiveness. The British Accounting Review, 41(4), 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoute, M., & Budding, T. (2017). Stakeholders’ information needs, cost system design, and cost system effectiveness in Dutch local government. Financial Accountability & Management, 33(1), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seal, W., & Mattimoe, R. (2011). Management accounting research in the hospitality sector. In M. Abdel-Kader (Ed.), Review of Management Accounting Research (pp. 497–520). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U. (2003). Research methods for business: A skill-building approach. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Sevima, A., & Korkmaz, E. (2014, May 15–18). Cost management practices in the hospitality industry: The case of the Turkish hotel industry. Global Interdisciplinary Business-Economics Advancement Conference (GIBA), Conference Proceedings, Istanbul, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D. S. (2002). The differential effect of environmental dimensionality, size, and structure on budget system characteristics in hotels. Management Accounting Research, 13(1), 101–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, D. F., Huang, G. Q., & Perks, R. (1991). Design for cost: Past experience and recent development. Journal of Engineering Design, 2(2), 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvola, H. (2008). Do organizational life-cycle and venture capital investors affect the management control systems used by the firm? Advances in Accounting, 24(1), 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S., Baird, K., & Schoch, H. (2013). Management control systems from an organisational life cycle perspective: The role of input, behaviour and output controls. Journal of Management & Organization, 19(5), 635–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzioglu, B., & Chan, E. S. (2013). Toward understanding the complexities of service costing: A review of theory and practice. Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research, 11(2), 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, U. T., & Tran, H. T. (2022). Factors of application of activity-based costing method: Evidence from a transitional country. Asia Pacific Management Review, 27(4), 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nguyen, H., & Brooks, A. (1997). An empirical investigation of adoption issues relating to activity-based costing. Asian Review of Accounting, 5(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetchagool, W., & Buttarat, R. (2023). The effects of CFO characteristics and historical financial performance on the adoption of advanced costing practices: Evidence from Thai listed companies. Journal of Business, Innovation and Sustainability, 18(3), 254030. [Google Scholar]

- Wihinen, K. (2012). Exploring cost system design principles: The analysis of costing system sophistication in a pricing context [Doctoral dissertation, Tampere University of Technology]. [Google Scholar]

- Yigitbasioglu, O. M. (2017). Drivers of management accounting adaptability: The agility lens. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 13(2), 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zounta, S., & Bekiaris, M. G. (2009). Cost-based management and decision-making in Greek luxury hotels. Tourismos: An International Multidisciplinary Journal of Tourism, 4(3), 205–225. [Google Scholar]

| Study | Sample | Cost System Design | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drury and Tayles (2005) | UK firms | Cost system complexity | Product diversity, firm size, degree of product standardization, and industry type (particularly financial and service sectors) positively influence the complexity of cost systems. In contrast, competition, costing structure, and the importance of costing information for decision-making do not show any statistically significant effect. |

| Al-Omiri and Drury (2007) | UK manufacturing and service firms | Cost system sophistication | The importance of costing information for decision-making, the firm size, the competition and the industry (specifically financial sector) have a positive effect on the sophistication of cost systems. No significant relationship is found with IT quality, product diversity, or cost structure. |

| Pavlatos and Paggios (2009) | Greek hotel firms | Cost system functionality | The cost leadership strategy and the degree of use of cost data have a significant impact on the functionality of cost systems. No significant relationship is observed with firm size, competitive intensity, service range, or management status. |

| Ismail and Mahmoud (2012) | Egyptian manufacturing firms | Cost system sophistication | The importance of cost information for decision-making influences the level of sophistication of cost systems. No statistically significant effects are found for product range, competitive intensity, or cost structure. |

| Kuzey et al. (2019) | Turkey non-financial firms | Cost system functionality | Information technology usage, use of cost data, and the degree of budget usage positively affect cost system functionality. Competition has a statistically significant negative effect. Production complexity, firm size, and cost leadership strategy do not have any statistically significant effect. |

| Hadid and Hamdan (2022) | Syrian manufacturing firms | Cost system sophistication | A direct positive relationship exists between firm size and cost system sophistication, although this relationship is negatively moderated by firm age. Additionally, firm size indirectly affects cost system sophistication through product diversity. |

| Banhmeid and Aljabr (2023) | UK manufacturing firms | Cost system sophistication | The active role of management accountants and advanced manufacturing technology significantly impacts the sophistication of cost systems. |

| Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Job Position | Financial Managers | 11 | 7.8 |

| Internal and Financial Auditors | 7 | 5.0 | |

| Cost Accountants | 5 | 3.5 | |

| Accountants | 88 | 62.4 | |

| Other Roles | 30 | 21.3 | |

| Job Experience | 1–10 years | 68 | 48.2 |

| 11–20 years | 58 | 41.1 | |

| More than 20 years | 15 | 10.6 | |

| Educational Level | Secondary Education (High School) | 3 | 2.1 |

| Vocational Training Institute | 18 | 12.8 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 97 | 68.9 | |

| Postgraduate Degree | 23 | 16.3 | |

| Doctorate (PhD) | 0 | 0 | |

| Age Group | Under 35 | 25 | 17.7 |

| 35–44 | 65 | 46.1 | |

| 45–54 | 34 | 24.1 | |

| Over 55 | 17 | 12.1 | |

| Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Beds | 1–100 beds | 6 | 4.3 |

| 101–150 beds | 27 | 19.1 | |

| 151–300 beds | 79 | 56.0 | |

| Over 300 beds | 29 | 20.6 | |

| Star Rating | 5-star hotels | 46 | 32.6 |

| 4-star hotels | 69 | 48.9 | |

| 3-star hotels | 26 | 18.4 | |

| Management Status | Privately owned | 111 | 78.7 |

| Member of domestic hotel chain | 19 | 13.5 | |

| Member of international hotel chain | 11 | 7.8 | |

| Construct | Factor Loadings | Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSS | 0.800–0.891 | 0.775–0.833 | 0.853 |

| COMP | 0.635–0.792 | 0.557–0.694 | 0.851 |

| ICI | 0.772–0.862 | 0.851–0.878 | 0.886 |

| ITI | 0.905–0.909 | 0.800 | 0.889 |

| CSS | COMP | SIZE | CS | ICI | DIV | STRA | ITI | OLC | AGE | JT | EDU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSS | 1 | |||||||||||

| COMP | 0.168 * | 1 | ||||||||||

| SIZE | 0.385 ** | 0.004 | 1 | |||||||||

| CS | 0.388 ** | 0.168 * | 0.113 | 1 | ||||||||

| ICI | 0.417 ** | 0.040 | 0.211 * | 0.318 ** | 1 | |||||||

| DIV | 0.317 ** | 0.093 | 0.708 ** | 0.091 | 0.205 * | 1 | ||||||

| STRA | −0.059 | 0.108 | −0.199 * | 0.044 | 0.056 | −0.193 * | 1 | |||||

| ITI | 0.415 ** | 0.113 | 0.238 ** | 0.296 ** | 0.223 ** | 0.227 ** | −0.057 | 1 | ||||

| OLC | 0.215 * | 0.034 | 0.151 | 0.107 | 0.167 * | 0.125 | 0.150 | 0.049 | 1 | |||

| AGE | −0.224 ** | −0.043 | −0.136 | −0.108 | −0.074 | −0.060 | 0.168 * | −0.028 | −0.120 | 1 | ||

| JT | −0.280 ** | −0.104 | −0.133 | −0.127 | −0.120 | −0.049 | 0.137 | −0.102 | −0.137 | 0.783 ** | 1 | |

| EDU | 0.214 * | 0.192 * | 0.290 ** | 0.162 | −0.019 | 0.242 ** | −0.257 ** | 0.152 | 0.052 | −0.350 ** | −0.266 ** | 1 |

| Mean | 2.98 | 3.28 | 4.82 | 41.73 | 3.05 | 2.38 | 2.87 | 2.45 | 0.63 | 42.07 | 11.84 | 0.85 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.91 | 0.70 | 1.54 | 13.52 | 0.84 | 0.58 | 1.22 | 0.97 | 0.48 | 8.37 | 6.71 | 0.36 |

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| Constant | 0.401 | 0.607 | 0.659 | 0.511 | |||

| COMP | 0.104 | 0.092 | 0.080 | 1.127 | 0.262 | 0.887 | 1.127 |

| SIZE | 0.118 | 0.058 | 0.199 | 2.021 | 0.045 | 0.459 | 2.177 |

| CS | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.178 | 2.393 | 0.018 | 0.808 | 1.238 |

| ICI | 0.248 | 0.080 | 0.228 | 3.085 | 0.002 | 0.815 | 1.228 |

| DIV | 0.041 | 0.152 | 0.026 | 0.268 | 0.789 | 0.474 | 2.110 |

| STRA | −0.012 | 0.055 | −0.016 | −0.219 | 0.827 | 0.835 | 1.197 |

| ITI | 0.213 | 0.069 | 0.227 | 3.102 | 0.002 | 0.836 | 1.196 |

| OLC | 0.172 | 0.132 | 0.091 | 1.301 | 0.195 | 0.908 | 1.101 |

| AGE | −0.003 | 0.012 | −0.027 | −0.242 | 0.810 | 0.355 | 2.817 |

| JT | −0.018 | 0.015 | −0.129 | −1.176 | 0.242 | 0.370 | 2.706 |

| EDU | 0.059 | 0.200 | 0.023 | 0.296 | 0.767 | 0.726 | 1.377 |

| R = 0.652; R2 = 0.425; Adj R2 = 0.375; | |||||||

| F = 8.651; Sig. = 0.000; D-W = 1.733 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diavastis, I.E. What Drives Cost System Sophistication? Empirical Evidence from the Greek Hotel Industry. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070401

Diavastis IE. What Drives Cost System Sophistication? Empirical Evidence from the Greek Hotel Industry. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(7):401. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070401

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiavastis, Ioannis E. 2025. "What Drives Cost System Sophistication? Empirical Evidence from the Greek Hotel Industry" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 7: 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070401

APA StyleDiavastis, I. E. (2025). What Drives Cost System Sophistication? Empirical Evidence from the Greek Hotel Industry. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(7), 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070401