Abstract

This study examines the impact of cost stickiness on research and development (R&D) investment and corporate performance in Japanese firms. Additionally, it investigates the moderating effect of managerial overconfidence and financial slack. To do so, we analysed a sample of 4877 observations from Japanese firms listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange between 2014 and 2020. The results show that cost stickiness generally promotes R&D investment while negatively affecting corporate performance. Further, although managerial overconfidence does not moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment, it weakens the negative effect of cost stickiness on corporate performance. Meanwhile, financial slack strengthens the positive impact of cost stickiness on R&D investment, but it does not moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance. These findings provide strategic insights into resource allocation behaviour in driving innovation and influencing corporate outcomes in the Japanese market context.

1. Introduction

Cost stickiness occurs when cost increases more with rising demand than it decreases with falling demand (Anderson et al., 2003). This phenomenon challenges the assumptions of traditional accounting theory regarding cost behaviours. As costs represent limited economic resources, improving cost management is crucial for enhancing corporate performance.

Prior studies have focused on formative factors contributing to cost stickiness, often viewing this phenomenon negatively through the perspective of traditional cost behaviour theory. These studies have identified both internal factors (e.g., cost type, cost structure, capacity utilisation) and external factors (e.g., macroeconomic background and legal environment) as contributors to cost stickiness. For instance, Anderson et al. (2003), analysing data from U.S. firms, found evidence of cost stickiness, where the absolute rate of decrease in selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses when sales decrease is less than the absolute rate of increase in costs when activity increases. However, subsequent research provided evidence of anti-cost stickiness, where the absolute rate of decrease in SG&A expenses when sales decrease is greater than the absolute rate of increase in costs when activity increases (Balakrishnan et al., 2004), a contrary finding that makes the phenomenon more comprehensive. In the Japanese context, empirical research has shown evidence of anti-cost stickiness in local public corporations (Hosomi & Nagasawa, 2018).

While these studies provide a foundational understanding of why costs stick and how their behaviour varies, a notable gap remains in understanding the economic consequences of cost stickiness, particularly its role as a strategic resource for innovation investment and its ultimate impact on corporate performance. This research gap is particularly relevant in contexts where firms operate under unique strategic and financial landscapes, such as Japanese firms, which often prioritise long-term employment stability and growth over short-term cost optimisation.

To address this gap, this study uniquely investigates the economic consequences of cost stickiness as an incentive for research and development (R&D) investment and its implications for corporate performance in Japanese firms. This study develops a comprehensive framework by integrating organisational slack theory, the resource-based view (RBV), and agency theory. According to organisational slack theory, slack serves as a buffer against the risk and uncertainties inherent in R&D activities (Geiger & Makri, 2006). In this context, the RBV states a complementary perspective, suggesting that cost stickiness may generate slack resources that support self-organisation and self-repair, and provide the necessary inputs for innovation (Collis & Montgomery, 2005). Furthermore, agency theory is particularly relevant in explaining how managerial discretion may lead to overinvestment in risky projects such as R&D activities driven by the optimistic biases, especially among overconfident managers (Chen et al., 2022). Specifically, this study aims to clarify the role of cost stickiness in reallocating resources toward R&D investment, examine how firm characteristics (managerial overconfidence and financial slack) influence this relationship, and investigate its impact on corporate performance. Through this theoretical integration and context-specific analysis, this study strengthens the theoretical understanding of cost stickiness by focusing on its economic impact and offers strategic insights for improving cost management efficiency, and enhances managerial decision-making in the Japanese market context.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Literature Review

Prior studies focused on factors shaping cost stickiness, especially for agency costs, managers’ optimistic expectations, and adjustment costs.

Agency costs arise when shareholders are unable to thoroughly monitor managers’ actions or rigorously evaluate their results. Fukuda (2018) notes that when agency costs exist, managers may hold cash to increase their discretion, rather than returning surplus funds to shareholders as dividends, even if this reduces corporate value. Chen et al. (2012) examined internal factors such as free cash flow, CEO tenure, and pay structure as managerial ‘empire building’ variables that contribute to cost stickiness through agency costs. When sales increase, managers may raise agency costs by increasing their compensation and using the firm’s resources for personal benefit. Conversely, when operating activity decreases, managers tend to maintain compensation and existing resources to avoid negatively impacting future sales, which results in cost stickiness.

Management’s optimistic expectations refer to the decision to retain slack due to expected internal information suggesting improved future performance, particularly when sales decline temporarily. Reducing slack can help meet short-term profit targets but may require repurchasing resources when long-term production recovers. Keeping slack avoids re-procurement costs but causes cost stickiness. A better economic environment increases managers’ optimistic expectations and cost stickiness. Conversely, reduced uncertainty about future demand decreases cost stickiness (Kama & Weiss, 2013). Banker et al. (2013) examined how changes in sales direction affect managers’ predictions of future demand. They found that when the direction of sales aligns with management’s forecast, it increases future expectations and cost stickiness. Conversely, a mismatch weakens expectations and reduces cost stickiness. Furthermore, overconfident managers tend to be more optimistic about future demand, thus increasing cost stickiness. Balakrishnan and Gruca (2008) pointed out that managers with a longer-term outlook for business performance tend to maintain SG&A expenses even in the face of declining sales, which may cause cost stickiness. Banker et al. (2025) provided evidence that firms pursuing a differentiation strategy exhibit greater cost stickiness on average than those pursuing a cost leadership strategy. This relationship is moderated by managers’ optimistic or pessimistic expectations for future sales.

Firms adjust costs in response to sales changes, incurring adjustment costs. These include upward adjustments (e.g., machinery purchases and employee increases) and downward costs adjustments (e.g., equipment impairment, layoffs). Adjustment costs affect the range of cost changes and lead to managers’ caution in reducing costs during sales declines due to high replacement costs. This slower cost adjustment causes short-term cost stickiness, as slack accumulates during gradual reductions. Capital and labour intensity are positively correlated with cost stickiness, as higher intensity increases downward adjustment costs (Anderson et al., 2003). Cost stickiness may incentivise managers to reduce product prices and utilise excess production capacity when demand falls. Conversely, when demand rises, managers may raise product prices and expand production capacity to avoid greater adjustment costs with rebuilding capacity (Cannon, 2014). Firms’ cost types and structures also influence adjustment costs and cost stickiness differently. Banker and Byzalov (2014) revealed that cost stickiness is significantly affected by cost structures, including selling, R&D, labour, advertising, equipment costs, S&G expenses, and those in special industries such as medical, aviation, and financial services. Different cost types exhibit varied behaviours. A higher proportion of fixed cost in a firm’s cost structure leads to higher downward adjustment costs, reduced motivation to adjust cost, and increased cost stickiness (Banker et al., 2014a, 2014b).

2.2. Hypotheses Development

R&D activities, initiated through resource inputs, are central to resource allocation and involve making investment decisions driven by profit maximisation and innovation (Hitt et al., 1997). However, prior studies on the factors affecting R&D have not sufficiently considered firms’ internal resources, focusing instead on the slack viewpoint (Nohria & Gulati, 1996; Wang et al., 2017). Additionally, potential risks may influence managers’ R&D investment decisions. Cost stickiness, defined as the asymmetric response of costs to changes in sales (i.e., costs increase more with sales growth than they decrease with sales decline), implies the presence of organisational slack.

According to organisational slack theory, slack provides a buffer for innovation (Geiger & Makri, 2006), enabling managers to utilise idle resources effectively. It reduces the risks associated with experimental projects, thereby encouraging firms to invest in R&D activities and pursue risky ideas.

The RBV further offers a strategic perspective on how firms allocate resources to R&D activities. It states that sustainable competitive advantage comes from unique, valuable, and inimitable internal capabilities. These capabilities are mainly developed through R&D activities (Collis & Montgomery, 2005). Cost stickiness, by generating slack, offers managers gain a resource buffer. Although the underutilised resources (e.g., specialised personnel or equipment) arising from cost stickiness may not be directly applied to R&D activities, their continued presence suggests that relevant budgets remain intact. This may free up financial capacity and allow managers to redeploy specific human capital (e.g., engineers) to innovation projects. Based on organisational slack theory and RBV, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Cost stickiness has a positive effect on firms’ R&D investment.

Cost stickiness suggests that resources are not optimally allocated in response to sales change. To improve resource alignment, managers may attempt to utilise slack more effectively. However, the degree to which cost stickiness stimulates R&D investment depends on firm-specific characteristics, particularly managerial overconfidence (Kunz & Sonnenholzner, 2023).

From the perspective of agency theory, such behavioural characteristics influence how managerial discretion impacts resource allocation decisions and the factors that induce R&D based on manager overconfidence.

From the perspective of agency theory, managers have discretion over company resources, and their decisions may deviate from the goal of maximising shareholder value. Overconfident managers tend to be overly optimistic in their forecasts, perceiving slack arising from overinvestment as normal (Chen et al., 2022). When business volume declines, overconfident managers may ignore slack and anticipate future growth driven by irrational optimism (Tebourbi et al., 2020). They see this as a way of leveraging existing resources to gain future competitive advantages, thereby lowering the incremental investment hurdle for new projects (Gervais et al., 2011). This is a low-cost way for them to gain future competitive advantages (Killins et al., 2021). From the agency theory perspective, this behaviour represents a form of overinvestment. Thus, managerial overconfidence leads to the deployment of idle resources generated by cost stickiness into R&D activities, moderating the positive relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Managerial overconfidence positively moderates the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment.

Financial slack refers to readily available or underutilised resources that are not tied to specific commitments (Nohria & Gulati, 1996). It enhances flexibility and reduces financial constraints, enabling managers to exercise greater discretion in resource allocation (George, 2005).

From the perspective of RBV, financial slack facilitates strategic investments, particularly in high-uncertainty activities such as R&D, by providing funding and reducing reliance on potentially more costly external financing (Ashwin et al., 2016). However, the presence of financial slack may also influence how firms utilise other internal resources. While these sticky resources are not easily redeployed into innovation, financial slack helps resolve this dilemma. It acts not only as a valuable static resource, but also as a dynamic capability, which refers to a firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments (Lin & Wu, 2014). In this context of high financial flexibility, management can leverage financial slack to identify, evaluate, and reconfigure these specific, less flexible, but uniquely valuable resources represented by cost stickiness, such as core technical personnel, specialised equipment, and proprietary knowledge. Financial slack provides the necessary strategic buffer by lowering the risks, opportunity costs, and switching costs associated with converting these sticky resources into high-risk R&D activities. It enables managers to “activate” internal capabilities represented by sticky resources into sources of innovation, rather than leaving them idle or eliminating them under financial pressure. Consequently, financial slack provides financial assurance and decision-making flexibility, thereby enhancing the strategic value of cost stickiness as an R&D investment driver, making its role in promoting R&D investment even more pronounced. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Financial slackpositivelymoderates the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment.

Although cost stickiness may stimulate strategic investment by providing slack resources, it can also have a direct, negative impact on firm performance. As a cost behaviour phenomenon, its impact on corporate performance is important research topics in management accounting.

According to resource adjustment theory, costs such as labour and equipment cannot be easily reduced when sales decline due to high adjustment costs. This leads to low resource utilisation efficiency and ultimately reduce profitability (Anderson et al., 2003; Balakrishnan et al., 2004).

Prior studies have shown that cost stickiness may lead to increased earnings volatility, higher default, and credit risk (Homburg et al., 2018). Analysts also find it difficult to recognise and incorporate the sticky nature of costs, which lower forecast accuracy (Ciftci & Salama, 2018), further implying the negative impact of cost stickiness on corporate performance. Costa and Habib (2023) revealed a strong negative relationship between cost stickiness and firm value in U.S. firms. They found that when sales decline, maintaining costs reduces the present value of sales and increases the opportunity cost of underutilised resources, finally leading to decreased profitability.

This study aims to examine whether this negative impact holds in the Japanese context, where a unique corporate culture emphasises employment stability and conservative resource adjustment. Based on resource adjustment theory, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Cost stickiness has a negative effect on corporate performance.

Managerial behavioural characteristics, especially cognitive biases, influence strategic decisions and financial outcomes.

From the perspective of behavioural finance, managerial overconfidence is a prevalent cognitive bias among managers, characterised as an inflated belief in their own judgement and abilities (Kunz & Sonnenholzner, 2023). It suggests that managerial expectations may moderate the effect of cost stickiness on firm value. This offers theoretical motivation to explore the role of managerial overconfidence in this relationship (Costa & Habib, 2023).

From the perspective of agency theory, overconfident managers may pursue cost management strategies that differ from rational expectations, especially when firms face declining sales. They may underestimate the persistence of cost stickiness or overestimate the firm’s capacity to recover through future growth (Tebourbi et al., 2020). Consequently, this optimistic bias may lead them to retain idle resources during downturns (Costa & Habib, 2023). However, this retention of resources does not necessarily translate into passive inefficiency. A core characteristic of overconfident managers is not just optimism, but a strong belief in their personal ability to control events and engineer success (Doukas & Petmezas, 2007). Faced with the clear, negative feedback of declining performance and driven by their cognitive bias, they are likely to engage in risk behaviours aimed at reversing the trend, rather than passive waiting. Their optimistic bias can prompt aggressive strategic decisions aimed at overcoming downturns, such as entering new markets, investing in innovation, or expanding capacity despite short-term setbacks (Kunz & Sonnenholzner, 2023). By deploying otherwise idle resources into such high-risk, high-return projects, they may generate new revenue streams and enhance the firm’s long-term operational flexibility (J. M. Lee et al., 2023).

Thus, while overconfidence may introduce risk, its inherent tendency toward action in the face of challenges suggests that this proactive risk-taking might offset some of the efficiency losses, thereby weakening the negative association between cost stickiness and corporate performance, especially when managers’ decisions are forward-looking and strategically bold. Based on behavioural finance and agency theory, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Managerial overconfidencenegatively moderates the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance.

When firms face efficiency losses in resource utilisation and potential performance harm due to cost stickiness, financial slack acts as a valuable resource. It provides significant strategic flexibility and buffers (Gral & Gral, 2014).

From the perspective of RBV, financial slack acts as a safety net. It helps the company absorb efficiency losses from sticky costs and prevents immediate financial distress. Moreover, it enables the company to cover necessary restructuring expenses or invest in projects such as technological upgrades and process optimisation (Liang et al., 2023). These strategic actions may address the cost stickiness problem and reduce its negative impact on corporate performance.

From the perspective of crisis management theory, cost stickiness during sales declines generates profit pressure and creates a crisis situation. Under these circumstances, financial slack provides a valuable breathing room for management (Gruener & Raastad, 2018), thereby preventing the company from making rushed, potentially damaging cost-cutting decisions under pressure. Instead, financial slack gives management the time and resources to plan and implement more effective strategic adjustments. Such adjustments might include seeking new revenue sources, optimising the supply chain, or making selective investments, thereby offsetting the negative impact of cost stickiness over a longer time horizon and even transforming it into future competitive advantages.

Therefore, financial slack can ultimately reduce the negative effects of cost stickiness on corporate performance by providing strategic buffers and supporting effective strategic adjustments in crisis situations. Based on the perspectives of RBV and crisis management theory, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Financial slack negatively moderates the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance.

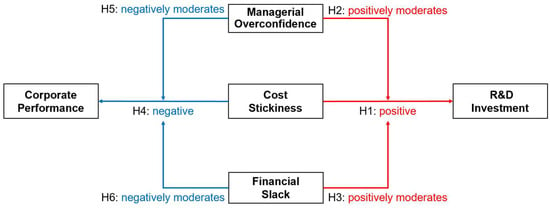

Figure 1 presents the research model.

Figure 1.

Research model. Note: Red indicates a positive impact or moderating effect, and blue indicates a negative impact or moderating effect.

3. Method

3.1. Dependent Variables

3.1.1. R&D Investment

R&D activities involve efforts to create and improve products in order to achieve better results and increase product value (Basgoze & Sayin, 2013). Innovation within a company is defined as a significant improvement in product quality or production process (Busch & Schnippering, 2022). Successful R&D activities lead to new products or services, enabling companies to differentiate themselves from competitors.

R&D investment is measured by R&D intensity, defined as the expenses a company incurs to conduct R&D activities. R&D intensity is a valuable instrument for assessing corporate innovation and growth investment (De Santis & Presti, 2018). It is broadly recognised as an important factor boosting economic growth and enhancing sales revenue (Ghisetti & Pontoni, 2015). Companies invest in R&D primarily to encourage innovation, which in turn increases sales revenue. These R&D activities commonly lead to the expansion of innovative products, allowing corporations to sustain their effectiveness and seize market opportunities. The variable used as a proxy for R&D investment is calculated as follows:

This model effectively reflects the amount of R&D expenses relative to its sales revenue (Busch & Schnippering, 2022).

3.1.2. Corporate Performance

Firms pursuing in long-term management strategies often enter various long-term contracts, which may lead to cost stickiness, where expenses increase with business activity but decrease only slightly when business activity declines, due to contractual obligations. This phenomenon, along with economic inefficiency and agency costs arising from asymmetric interests, also prevents cost reduction during business activity decreases. Thus, cost stickiness is negatively correlated with short-term corporate performance.

To measure this corporate performance, this study uses Return on Assets (ROA). ROA provides a broader measure of how efficiently a company utilises its assets to generate profits from its entire operations, including all expenses (Magni, 2015). The variable ROA, used as a proxy for corporate performance, is calculated as follows:

3.2. Independent Variables

3.2.1. Cost Stickiness

Cost stickiness describes the asymmetric behaviour of costs when sales change. This study uses Weiss (2010)’s cost stickiness model to quantitively analyse this phenomenon. The variable used as a proxy for cost stickiness, is calculated as follows:

Here, represents the most recent quarter of sales decline within the last four quarters, and represents the most recent quarter of sales increase within the last four quarters.

In this model, represents the company’s business activity volume, calculated as . Following Weiss (2010), refers to sales revenue in this study. calculated as . Here, is income before extraordinary item (Weiss, 2010). However, according to the methodology of the Weiss (2010)’s model, noise may be introduced if non-operating income or expenses influence earnings. To eliminate such noise and to capture managerial choices affecting the costs of manufacturing goods, providing services, and marketing and distribution, refers to operating expenses in this study (Kama & Weiss, 2013). In addition, and serve as proxy variables, indicating that the volume of sales revenue and operating expenses change simultaneously in the same direction. In this context, a negative value with a larger absolute magnitude for indicates a clearer expression of cost stickiness. This implies that operating expenses decrease less proportionally when sales decline compared to how much they increase when sales rise.

3.2.2. Managerial Overconfidence

Regarding management’s expectations, Japanese listed firms report corporate performance forecasts in their financial statements, including expected operating activities and profits for the next fiscal year. In addition, third-party forecasts, such as the Toyo Keizai corporate performance forecast, do not reflect the management’s intentions. Instead, they provide objective and neutral sales and profit estimates to compare with corporate forecasts and demonstrate how overconfident managers are impacted. These forecasts, released during fiscal year t, are made for the next fiscal year (t + 1). Thus, this chronological order helps to mitigate the potential simultaneity bias between the optimism variable and other variables measured in period t.

Specifically, managerial overconfidence is measured as: (Toyo Keizai’s forecast operating profit—the company’s forecast operating profit) divided by the company’s forecast operating profit, expressed as a percentage. Based on this percentage deviation, five attitudes towards future risks are distinguished as follows, where a negative deviation indicates managerial overconfidence (company’s forecast is more optimistic than Toyo Keizai’s) and a positive deviation indicates managerial conservatism (company’s forecast is less optimistic than Toyo Keizai’s): ‘−30% or less’ indicates quite overconfident management; ‘−3% to less than −30%’ indicates overconfident management; ‘−3% to less than +3%’ indicates neutral management; ‘+3% to less than 30%’ indicates conservative management; and ‘+30% or more’ indicates quite conservative management. A qualitative ordinal variable is used to capture the managerial overconfidence level: ‘2’ for quite overconfident management; ‘1’ for overconfident management; ‘0’ for neutral management; ‘−1’ for conservative management; and ‘−2’ for quite conservative management. Thus, these quantitative data are treated as an interval scale, similar to a Likert scale.

3.2.3. Financial Slack

Financial slack refers to an organisation’s liquid assets, such as cash and deposits, that are not allocated to specific operation or investment (Kraatz & Zajac, 2001). An important aspect of efficient management is using an organisation’s existing slack resources to reduce the effects of external pressures on corporations, while simultaneously making efforts to seize corporate opportunities. Therefore, the existence of idle resources is a major source of effective financial changes, and it plays a crucial role in enhancing operating performance (De Jong et al., 2012).

This study uses the ratio of cash and deposits to current liabilities to proxy financial slack. This measure reflects the firm’s unabsorbed slack not used for specific activities and its capacity to fund short-term operations and investments. There are three primary reasons for selecting this measure in the Japanese context. First, Japanese firms have long made little capital investment, following the economic uncertainty after Lehman shock, resulting in large cash and deposit holdings. This trend highlights the availability of substantial internal liquidity. Second, due to optimistic expectations or preliminary motives, managers save on transaction costs by raising capital and maintain highly liquid cash and its equivalents for flexibility, particularly when anticipating promising future investment opportunities, such as precautionary or flexibility motives. This aligns with motives for holding slack resources. Third, cash flow reflects agency problem. As a type of financial slack, managers have an incentive to keep free cash flows to pursue private interests rather than distributing surplus funds to shareholders through dividends (Fukuda, 2018). The variable, used as proxy for financial slack, is calculated as follows:

Table 1 presents detailed definitions and measurements for all variables.

Table 1.

Variable definitions and measurements.

3.3. Samples

This study tests the hypotheses using financial data from Japanese firms listed on the first and second sections of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. The sample excludes banking, insurance, securities and other financial services industries. The analysis covers the period from 2014 to 2020, considering COVID-19’s potential impact on R&D investment. Data were obtained from the Nikkei NEEDS-Financial QUEST database and ‘Kaisha Shikiho’ (Japan Company Handbook published by Toyo Keizai Inc, Tokyo, Japan).

The study extracted firms based on the following criteria: (1) listed firms that adopt Japanese accounting standards, with complete financial data from 2014 to 2020, a fiscal year ending in March and a 12-month reporting period; (2) firms with sufficient quarterly data to calculate cost stickiness using the Weiss model (Weiss, 2010); and (3) firm for which a qualitative ordinal measure of managerial overconfidence, based on the forecast deviation rate in Kaisha Shikiho, was available.

To ensure robustness in regression results and mitigate the potential influence of extreme values, outliers in all continuous financial variables were addressed. Following the 3-sigma rule, outliers were identified as observations whose values fell more than three standard deviations above or below the variable’s mean. These identified outliers were then removed from the dataset. This approach helps to reduce the undue impact of extreme observations.

Table 2 presents a comparison of the sample by year. Table 3 presents basic statistics for each variable.

Table 2.

Comparison of sample by year.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

3.4. Analysis Procedures

In all regression models, the dependent variables (R&D intensity and ROA) are measured in period t + 1, while the independent variables (cost stickiness, optimism, cash to debt) and control variables are measured in period t. This lag structure helps mitigate potential endogeneity concerns, particularly reverse causality between explanatory and outcome variables.

The primary analysis uses pooled ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions (models 1–12, presented in Table 4 and Table 5), to examine the impact of cost stickiness on R&D investment and corporate performance, and the moderating effects of managerial overconfidence, and financial slack.

Table 4.

Relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment and the moderating effect of managerial overconfidence and financial slack (pooled OLS models).

Table 5.

Relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance and the moderating effect of managerial overconfidence and financial slack (pooled OLS models).

To assess the appropriateness of fixed effects models over pooled OLS, and to determine whether two-way (firm and year) fixed effects are preferable to one-way (firm) fixed effects, F-tests (models 1–12, presented in Table 6) are conducted.

Table 6.

F test.

To address potential issues of unobserved firm-specific and time-specific heterogeneity and to strengthen causal inference for time-varying variables, two-way (firm and year) fixed effects (models 1’–12’, presented in Table 7 and Table 8) are used as robustness checks.

Table 7.

Relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment and moderating effect of managerial overconfidence and financial slack (two-way fixed effects model).

Table 8.

Relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance and the moderating effects of managerial overconfidence and financial slack (two-way fixed effects model).

By employing these multi-layered analytical approaches, this study aims to provide robust and reliable evidence on the complex relationships among cost stickiness, managerial overconfidence, and financial slack, as well as their implications for R&D investment and corporate performance.

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Relationship Between Cost Stickiness and R&D Investment

Model 1 (see Table 4) tests H1 by examining the impact of cost stickiness on R&D investment. The core independent variable, sticky, is calculated using the Weiss model. Its negative values indicate cost stickiness is present, with a larger absolute value indicating greater cost stickiness. Consequently, a negative coefficient suggests that higher cost stickiness is associated with increased greater R&D intensity.

The regression results show that the coefficient for sticky β1 is −0.4070, significant at the 1% level, providing strong support for H1. This suggests that firms with greater cost stickiness tend to allocate more resources to R&D intensity in subsequent periods. Regarding the control variables, the industry dummy has a significant positive effect on R&D intensity, with a coefficient β6 of 1.780, significant at the 1% level. This indicates that manufacturing firms show significantly higher R&D investment than non-manufacturing firms. The coefficient for size β7 is 0.1496, significant at the 10% level, indicating a positive association with R&D intensity. The coefficient for Intangible β9 is 0.1023, significant at the 1% level, suggesting that firms with more intangible assets, such as patents or technical expertise, tend to invest more in R&D activities. This could be because intangible assets are products of R&D, or their presence encourages further R&D to maintain a competitive advantage. Conversely, Leverage has a negative effect on R&D intensity, with a coefficient β8 of −0.1562, significant at the 1% level. This suggests that leveraged firms tend to reduce R&D intensity, possibly due to increased financial constrains or risk aversion.

In summary, H1 is supported. Cost stickiness has a significant positive effect on a firm’s R&D investment. This means that when a firm’s cost stickiness is higher, its future R&D investment tends to be greater.

4.2. Firm Moderating Effects on the Relationship Between Cost Stickiness and R&D Investment

4.2.1. Moderating Effects of Managerial Overconfidence on the Relationship Between Cost Stickiness and R&D Investment

Models 2 and 3 test H2 by examining whether how managerial overconfidence moderates the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment. These models extend model 1 by adding optimism, a proxy of managerial overconfidence, and its interaction with sticky, while maintaining the same set of control variables.

Model 2 focuses on the direct impact of managerial overconfidence on R&D investment. The regression results show that the coefficient for sticky β1 is −0.4044, significant at the 1% level, consistent with the finding in model 1. The coefficient for optimism β2 is 0.1649, significant at the 5% level. This suggests that overconfident managers tend to invest more in R&D activities. The adjusted R-squared for model 2 is 0.21784, an increase from 0.21722 in model 1, indicating an improvement in explanatory power.

Model 3 focuses on whether the effect of cost stickiness on R&D investment is moderated by managerial overconfidence. The regression results show that the coefficient for Sticky β1 is −0.4011, significant at the 1% level, consistent with the finding in Model 1. Similarly, the coefficient for Optimism β2 is 0.1694, significant at the 5% level, consistent with the finding in model 2. However, the coefficient for the interaction term sticky × optimism β3 is 0.2760, not statistically significant. This suggests that managerial overconfidence does not moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment.

In summary, H2 is not supported. Managerial overconfidence directly promotes R&D investment, but it does not significantly moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment.

4.2.2. Moderating Effects of Financial Slack on the Relationship Between Cost Stickiness and R&D Investment

Models 4 and 5 test H3 by examining whether financial slack moderates the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment. These models extend model 1 by adding cash to debt, a proxy for financial slack, and its interaction with sticky, while maintaining the same set of control variables.

Model 4 focuses on the direct impact of financial slack on R&D investment. The regression results show that the coefficient for sticky β1 is −0.3997, significant at the 1% level, consistent with the finding in model 1. The coefficient for cash to debt β4 is 0.6386, significant at the 1% level. This suggests that firms with higher financial slack tend to invest more in R&D activities. The adjusted R-squared for model 4 is 0.24075, an increase from 0.21722 in model 1, indicating an improvement in explanatory power.

Model 5 focuses on whether the effect of cost stickiness on R&D investment is moderated by financial slack. The regression results for model 5 show that the coefficient for sticky β1 is −0.1436, not statistically significant. These results indicate that when financial slack and its interaction are included in the model, the significant positive effect of cost stickiness on R&D intensity observed in previous models becomes conditional upon the level of financial slack. The coefficient for cash to debt β4 is 0.6156, significant at the 1% level, consistent with the finding in model 4. Importantly, the coefficient for the interaction term sticky × cash to debt β5 is −0.4633, significant at the 10% level. The negative sign indicates that as financial slack increases, the positive relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment tends to strengthen. This indicates a conditional relationship in which the direct positive effect of cost stickiness on R&D intensity appears and increases when firms have higher levels of financial slack. Specifically, at higher levels of financial slack, cost stickiness is associated with increased R&D investment, suggesting that financial slack activates the buffer role of sticky costs for R&D. This moderating effect clarifies the main effects, suggesting that for firms with higher liquidity, the impact of cost stickiness on R&D investment is more pronounced, possibly because they have more flexible financial resources. It is important to note that the main effect of sticky reflects its influence when cash to debt is at a zero-level. Given that cash to debt typically deviates from zero, the statistical insignificance of the main effect of sticky does not contradict prior findings but rather highlights the conditional nature of the relationship.

In summary, H3 is supported. Financial slack positively affects R&D investment and enhances the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment.

4.2.3. Moderating Effects of Managerial Overconfidence and Financial Slack on the Relationship Between Cost Stickiness and R&D Investment

Model 6 integrates the variables from models 1 to 5 to examine their combined effects on R&D investment. The regression results show that the coefficient for sticky β1 is −0.1396, not statistically significant, consistent with the finding in model 5. The coefficient for optimism β2 is 0.1658, significant at the 5% level, consistent with the findings in Models 2 and 3, underscoring that managerial overconfidence has a direct positive effect on R&D investment. The coefficient for cash to debt β4 is 0.6152, significant at the 1% level, consistent with the findings in models 4 and 5, underscoring that financial slack has a direct positive effect on R&D investment. Regarding the interaction terms, the coefficient for sticky × optimism β3 is 0.1197, not statistically significant, consistent with the finding in model 3, underscoring that managerial overconfidence does not significantly moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment. The coefficient for sticky × cash to debt β5 is −0.4633, significant at the 10% level, consistent with the finding in model 6, confirming that financial slack does significantly continue to play a moderating role in the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment.

In summary, H2 is not supported, however H3 is supported. Managerial overconfidence has a direct positive effect on R&D investment but does not significantly moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment. Meanwhile, financial slack not only has a direct positive effect on R&D investment, but also positively moderates the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment.

4.3. The Relationship Between Cost Stickiness and Corporate Performance

Model 7 (see Table 5), which tests H4, replaces the dependent variable with ROA for the next period, instead of R&D intensity in model 1, to examine the direct impact of cost stickiness on corporate performance.

The regression results show that the coefficient for sticky β1 is 0.2730, not statistically significant. This suggests that cost stickiness does not have a statistically significant direct relationship with corporate performance in this model. Regarding the control variables, the coefficient for size β7 is 0.5470, significant at the 1% level, indicating that larger firms tend to achieve higher corporate performance. The coefficient for Intangible β9 is 0.1156, significant at the 1% level, suggesting that firms with more intangible assets tend to achieve higher corporate performance. This could be because intangible assets enhance performance or encourage innovation to maintain a competitive advantage. Conversely, the industry dummy has a significant negative effect on corporate performance, with a coefficient β6 of −0.9455, significant at the 1% level. This indicates that manufacturing firms generally show lower ROA than non-manufacturing firms. Leverage also shows a significant negative effect on ROA, with a coefficient β8 of −0.9315, significant at the 1% level, indicating that higher debt levels are associated with reduced performance, possibly due to reduced financial flexibility or risk aversion

In summary, H4 is not supported. Cost stickiness does not have a direct relationship with corporate performance.

4.4. Firm Moderating Effects on the Relationship Between Cost Stickiness and Corporate Performance

4.4.1. Moderating Effects of Managerial Overconfidence on the Relationship Between Cost Stickiness and Corporate Performance

Models 8 and 9 test H5 by examining whether managerial overconfidence moderates the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance.

Model 8 focuses on the direct impact of cost stickiness and managerial overconfidence on corporate performance. The regression results show that the coefficient for sticky β1 is 0.2520, not statistically significant, consistent with the finding in model 7. The coefficient for optimism β2 is −1.316, significant at the 1% level, suggesting that managerial overconfidence has a significant negative effect on corporate performance. The adjusted R-squared for model 8 is 0.10023, an increase from 0.08566 in model 7, indicating an improvement in explanatory power.

Model 9 focuses on whether the effect of cost stickiness on corporate performance is moderated by managerial overconfidence. The regression results show that the coefficient for sticky β1 is 0.2382, not statistically significant, consistent with the findings in models 7 and 8. Similarly, the coefficient for optimism β2 is −1.335, significant at the 1% level, consistent with the finding in model 8. However, the coefficient for the interaction term sticky × optimism β3 is −1.168, not statistically significant. This suggests that managerial overconfidence does not moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance.

In summary, H5 is not supported. Managerial overconfidence directly decreases corporate performance, but it does not significantly moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance.

4.4.2. Moderating Effects of Financial Slack on the Relationship Between Cost Stickiness and Corporate Performance

Models 10 and 11 test H6 by examining whether financial slack moderates the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance.

Model 10 focuses on the direct impact of financial slack on corporate performance. The regression results show that the coefficient for sticky β1 is 0.2811, not statistically significant, consistent with the findings in models 7 to 9. The coefficient for cash to debt β4 is 0.7089, significant at the 1% level. This suggests that firms with higher financial slack tend to have better corporate performance. The adjusted R-squared for model 10 is 0.09415, an increase from 0.08566 in model 7, indicating an improvement in explanatory power.

Model 11 focuses on whether the effect of cost stickiness on corporate performance is moderated by financial slack. The regression results show that the coefficient for sticky β1 is 0.1202, not statistically significant, consistent with the findings in models 7 to 10. The coefficient for cash to debt β4 is 0.7233, significant at the 1% level, consistent with the finding in model 10. Importantly, the coefficient for the interaction term sticky × cash to debt β5 is 0.2911, not statistically significant. This suggests that financial slack does not significantly moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance.

In summary, H6 is not supported. Financial slack directly enhances corporate performance, but it does not significantly moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance.

4.4.3. Moderating Effects of Managerial Overconfidence and Financial Slack on the Relationship Between Cost Stickiness and Corporate Performance

Model 12 integrates the variables from models 7 to 11 to provide a comprehensive analysis of their combined effects on corporate performance. The regression results show that the coefficient for sticky β1 is 0.0848, not statistically significant, consistent with the findings in models 7 to 11, underscoring that cost stickiness does not have a direct statistically significant effect on corporate performance. The coefficient for optimism β2 is −1.339, significant at the 1% level, consistent with the findings in models 8 and 9, underscoring that managerial overconfidence has a direct and significant negative relationship with corporate performance in this combined model. The coefficient for cash to debt β4 is 0.7270, significant at the 1% level, consistent with the findings in models 10 and 11, underscoring that financial slack has a direct and significant positive relationship with corporate performance. Regarding the interaction terms, the coefficient for sticky × optimism β3 is −1.303, not statistically significant. This is consistent with the finding in model 9, underscoring that managerial overconfidence does not significantly moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance. The coefficient for sticky × cash to debt β5 is 0.2894, not statistically significant. This further suggest that financial slack does not significantly moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance.

In summary, H5 and H6 are not supported. Managerial overconfidence has a direct negative effect on corporate performance but does not significantly moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance. Meanwhile, financial slack has a direct positive effect on corporate performance, but it does not significantly moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance.

4.5. Robustness Checks

The main analyses (models 1–12) are conducted using pooled OLS regressions, which assume that no unobserved characteristics over time. However, if such unobserved firm-specific and time-specific characteristics exist, and correlated with variables such as cost stickiness, managerial overconfidence, or financial slack, then the estimates obtained through pooled OLS estimates may be biased and inconsistent. To address this issue of potential unobserved heterogeneity and strengthen the causal interpretation of time-varying variables, robustness checks are conducted using fixed effects models (models 1’ to 12’).

4.5.1. F Test

The results (see Table 6) strongly support the use of two-way fixed effects model, indicating that both firm-specific and time-specific effects are statistically significant and should be controlled for.

4.5.2. Two-Way Fixed Effects Model

In models 1’ to 6’ (see Table 7), where the dependent variable is R&D investment, the coefficient for sticky β1 remains consistently negative and statistically significant at the 5% level in model 1’ to 4’. Although their magnitudes are smaller than those observed in the pooled OLS models 1 to 4, the direction and statistical significance of the relationship remain robust, supporting the finding that greater cost stickiness continues to be associated with higher R&D investment, even after controlling for unobserved firm and time-specific heterogeneity. The coefficient for sticky β1 is consistently not statistically significant in models 5’ and 6’, consistent with the findings in pooled OLS models 5 and 6, implying that its effect is contingent upon the presence of financial slack. When the interaction term sticky × cash to debt is introduced, the interpretation of the main effect of Sticky reflects its impact when the moderator of cash to debt typically deviates from zero, the statistical insignificance of the main effect of Sticky does not necessarily negate the overall positive relationship observed across other robust specifications but rather suggests that its impact might be intertwined with the level of financial slack. This indicates that the effect of cost stickiness is dependent on the level of financial slack. This positive relationship exists primarily in firms that possess a certain level of financial buffer.

Regarding the moderating effects of managerial overconfidence on the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment, the coefficient of optimism β2 remains positive and significant in models 2’, 3’, and 6’, consistent with the findings in pooled OLS models 2, 3, and 6. It indicates the direct positive impact of managerial overconfidence on R&D investment. However, the interaction term sticky × optimism β3 remains not statistically significant in models 3’ and 6’, consistent with the findings in pooled OLS models 3 and 6. It indicates that managerial overconfidence does not significantly moderate the positive relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment.

Regarding the moderating effects of financial slack on the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment, the direct effect of cash to debt β4 is not statistically significant in models 4’ to 6’, in contrast to pooled OLS models 4 to 6. This indicates that the observed positive effect of financial slack on R&D investment might be more apparent in cross-sectional variation rather than within-firm changes over time. For example, companies with more financial slack tend to invest more in R&D, while liquidity increases from within the firm do not necessarily result in increases in R&D investments. Additionally, the interaction term sticky × cash to debt β5 is not statistically significant in models 5’ and 6’, in contrast to the significant findings in pooled OLS models 5 and 6 (at the 10% level), implying that the moderating role of financial slack in the cost stickiness-R&D relationship is not robust, once firm- and time-specific effects are controlled.

In models 7’ to 12’ (see Table 8), where the dependent variable is corporate performance, the coefficient for sticky β1 is positive and significant at the 1% level in model 7’ to 10’. Since more negative sticky values indicate greater cost stickiness, a positive coefficient indicates that higher cost stickiness reduces corporate performance after controlling for unobserved firm and time specific heterogeneity, such as natural advantage in cost control or industry-specific characteristics. Specifically, it suggests that within the same company, when its cost stickiness increases, its corporate performance tends to decrease. In this context, the existence of fixed costs makes it difficult for managers to quickly cut expenses when sales declines, thereby affecting profitability. However, the coefficient for sticky β1 is not statistically significant in models 11’ and 12’, consistent with the findings in pooled OLS models 7 to 12. This result indicates that while cost stickiness generally has a negative impact on corporate performance, its independent direct effect may be less apparent when financial slack and its potential interaction are simultaneously considered. Specially, when the interaction term sticky × cash to debt is introduced, the interpretation of the main effect of sticky changes. In this context, it represents influence when the moderator of cash to debt is at a zero-level. However, since the moderator of cash to debt in this study is generally not at zero, the statistical insignificance of the main effect of sticky does not necessarily negate the overall positive relationship observed across other robust specifications but rather suggests that its impact might be intertwined with the level of financial slack.

Regarding the moderating effects of managerial overconfidence on the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance, the coefficient of optimism β2 remains negative and significant at the 1% level in models 8’, 9’, and 12’, consistent with the findings in pooled OLS models 8, 9 and 12, indicating that the direct negative impact of managerial overconfidence on corporate performance. Furthermore, the interaction term sticky × optimism β3 is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level in models 9’ and 12’ after controlling for unobserved firm- and time-specific heterogeneity, in contrast to the non-significant findings in pooled OLS models 9 and 12. This indicates that managerial overconfidence weakens the negative effect of cost stickiness on corporate performance.

Regarding the moderating effects of financial slack on the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance, the coefficient of cash to debt β4 becomes negative and statistically significant in models 10’ to 12’, in contrast to pooled OLS models 10 to 12. This suggests that the direct positive effect of financial slack on corporate performance may not be robust after removing time-invariant firm fixed effects, potentially being more apparent in cross-sectional differences. For example, firms with greater financial slack may generally perform better; however, increases in financial slack within the same firm over time do not necessarily lead to improved performance. Additionally, the interaction term sticky × cash to debt β5 is not statistically significant in models 11’ and 12’, consistent with the findings in pooled OLS models 11 and 12. This indicates that financial slack does not significantly moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance.

In summary, the positive relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment generally remains robust in pooled OLS models, although the magnitude of the effect is reduced in fixed effects specifications. When financial slack and its interaction are introduced, the direct effect of cost stickiness becomes statistically insignificant, suggesting that its impact is conditional on firm-specific liquidity levels. Managerial overconfidence consistently shows a direct positive effect on R&D investment in the fixed effects models. Its moderating effect on the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment remains insignificant. However, the impact of financial slack on R&D investment is non-significant in fixed effects models, in contrast to the highly significant effect in pooled OLS. The moderating effect of financial slack on the cost stickiness and R&D relationship is also insignificant in fixed effects models, in contrast to the highly significant results in pooled OLS. A notable finding is that cost stickiness has a significantly negative effect on corporate performance in the fixed effects models after controlling for unobserved firm- and time-specific heterogeneity, an effect not observed in the pooled OLS models. The direct negative effect of managerial overconfidence on corporate performance remains consistently significant and robust. Additionally, the moderating effect of managerial overconfidence on the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance is statistically significant and negative in the fixed effects models after controlling for unobserved firm- and time-specific heterogeneity, an effect that is not observed in the pooled OLS models. This suggests that managerial overconfidence significantly weakens the negative impact of cost stickiness on corporate performance. Moreover, while the direct effect of financial slack on corporate performance is positive and highly significant in pooled OLS models, this impact is negative and statistically significant in fixed effects models, suggesting that the previously observed positive direct effect is not robust to controlling for unobserved firm-specific heterogeneity. Further, the moderating effect of financial slack on the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance is not statistically significant in both pooled OLS and fixed effects models.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Findings

This study investigates the economic consequences of cost stickiness by examining its effects on R&D investment and corporate performance in Japanese companies listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, which applied Japanese accounting standards from 2014 to 2020. It further explored how managerial overconfidence and financial slack influence these relationships. Drawing on organisational slack theory, the RBV, agency theory, and behavioural finance, the research provides a comprehensive understanding of how internal firm characteristics influence innovation and financial outcomes. Specifically, the findings confirm that cost stickiness acts as a driver of R&D investment (supporting H1) but also has a negative impact on corporate performance (supporting H4). While managerial overconfidence does not significantly moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment (rejecting H2), it weakens the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance (supporting H5). Financial slack strengths the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment in OLS models, although this effect is not robust in the fixed effects models, partially supporting H3. However, financial slack does not significantly moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance, thereby rejecting H6. These results together provide a clearer understanding of resource allocation strategies for innovation and contribute meaningfully to the literature on cost behaviour and strategic management.

Regarding H1, cost stickiness (sticky) has a statistically significant positive effect on R&D investment (R&D intensity), and this hypothesis is consistently supported across most results in the pooled OLS models 1 to 6 and two-way fixed effects models 1’ to 4’ models. These results imply that higher cost stickiness is associated with increased R&D investment (Ashwin et al., 2016; Yoon et al., 2022). This finding provides robust empirical support for H1. Further, the effect remains significant after accounting for various unobserved factors, affirming that companies with greater cost stickiness tend to invest more in R&D (Zhang et al., 2022). However, in advanced models including the interaction term of financial slack (models 5, 6, 5’, and 6’), the direct effect of sticky costs on R&D investment is no longer statistically significant. This suggests that the effect of cost stickiness is not independent, but contingent on the level of financial slack. The positive relationship exists primarily in those firms that possess a certain level of financial buffer. This finding aligns with organisational slack theory and the RBV, which view slack as a buffer and a potential source of competitive advantage.

Regarding H2, managerial overconfidence (optimism) consistently shows a direct positive impact on R&D investment across all pooled OLS models 2, 3, 6 and two-way fixed effects models 2’, 3’, 6’ (Zavertiaeva et al., 2018). However, it does not significantly moderate the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment in all models. This finding is consistent with agency theory, which suggests that overconfident managers tend to overestimate future returns and pursue riskier projects, including innovation.

Regarding H3, financial slack (cash to debt) demonstrates a significant positive direct relationship with R&D investment in pooled OLS models 4 to 6. However, this effect is not statistically significant in the fixed effects models 4’ to 6’, indicating that its direct impact is not robust to unobserved heterogeneity. Firms with higher financial slack tend to invest more in R&D activities, highlighting the importance of currently available funds (C.-L. Lee & Wu, 2016). Moreover, the moderating effect of financial slack on the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment is not statistically significant in two-way fixed effects models 5’ and 6’. This suggests that while financial slack may facilitate the reallocation of sticky costs toward innovation, its effect may primarily reflect cross-sectional differences rather than within firms changes over time (Li, 2011; Beladi et al., 2021).

Regarding H4, while the direct effect of sticky costs (sticky) on corporate performance (ROA) is not statistically significant in pooled OLS models 7 to 10, a key new finding from the two-way fixed effects models 7’ to 10’ that cost stickiness has a significant negative effect on corporate performance. This implies that, similar to the U.S. firms (Costa & Habib, 2023), higher cost stickiness is associated with lower profitability in Japanese firms, after controlling for unobserved heterogeneity. This robust finding in fixed effects models provides strong empirical support for H4, highlighting that sticky costs hinder resource efficiency and profitability, particularly during sales downturns.

Regarding H5, managerial overconfidence (Optimism) shows a significant negative direct effect on corporate performance across all pooled OLS models 8, 9 and 12 and two-way fixed effects models 8’, 9’ and 12’. This indicates that higher managerial overconfidence is consistently associated with lower profitability (Guluma, 2021). Furthermore, its moderator effect is significantly negative in the two-way fixed effects models 9’, and 12’, although not significant in pooled OLS models 9 and 12. This suggests that managerial overconfidence weakens the negative relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance after controlling for unobserved heterogeneity. This finding is particularly noteworthy, as overconfidence is generally associated with negative impact on performance. One possible explanation is that in the governance structure of Japanese firms, managerial actions are subject to stricter oversight (Nakamura, 2011). Consequently, overconfidence may be channelled into productive innovation rather than personal empire-building. From this perspective, the proactive and risk-taking tendencies of overconfident managers, when faced with the negative signal of cost stickiness, may be directed toward constructive strategies rather than reckless decisions. Such behaviour helps mitigate the adverse effects of cost stickiness on corporate performance, suggesting that managerial overconfidence, despite its bias, may serve a compensatory role under certain institutional conditions.

Regarding H6, financial slack has a positive direct effect on corporate performance in pooled OLS models 10 and 12. However, this effect is not robust in the two-way fixed effects models 10’ to 12’, where the coefficients are negative and statistically significant. This suggests that the previously observed positive direct effect of financial slack may be driven by cross-sectional differences rather than within-firm changes. Moreover, the moderating effect of financial slack on the relationship between cost stickiness and corporate performance remains not statistically significant in two-way fixed effects models 11’ and 12’. This result can be interpreted through the perspective of the agency theory of free cash flow (Jensen, 1986), which suggests that excessive financial slack, in the absence of sufficient profitable investment opportunities, may lead to managerial inefficiency, wasteful spending, or value-destroying projects, ultimately harming firm performance. This highlights that while firms with more liquidity may exhibit better performance in cross-sectional comparisons, increases in slack over time do not necessarily translate into improved performance.

In summary, the results consistently show that cost stickiness promotes R&D investment (supporting H1) but also reduces corporate performance (supporting H4). However, the moderating effects are not fully supported. On the one hand, managerial overconfidence does not significantly influence the relationship between cost stickiness and R&D investment (rejecting H2) but mitigates the negative impact of cost stickiness on corporate performance (supporting H5). On the other hand, financial slack does not robustly moderate the effects of cost stickiness on R&D investment (partially supporting H3) and has no significant moderating effect on corporate performance (rejecting H6). Overall, these findings suggest that while cost stickiness is often viewed as inefficient, it can also function as a strategic buffer, particularly when complemented by managerial optimism and financial slack. However, its long-term value depends on how effectively firms leverage slack resources and balance the trade-off between resource stability and performance efficiency. In the Japanese context, where long-term employment and organisational stability are deeply prioritised, these dynamics are especially pronounced.

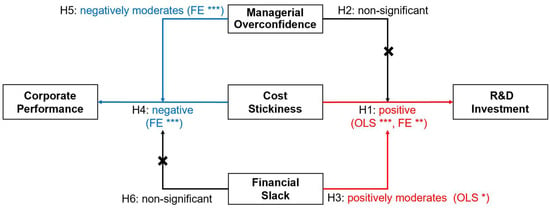

Figure 2 presents a summary of the research findings.

Figure 2.

Summary of research findings. Note: * Significance at the 10% level. ** Significance at the 5% level. *** Significance at the 1% level. Red indicates a positive impact or moderating effect, blue indicates a negative impact or moderating effect, and black indicates a non-significant result.

5.2. Implications

Between 2014 and 2020, Japanese companies reduced R&D spending due to economic conditions (Imahashi et al., 2018). This study identifies important internal factors that positively impact R&D investment.

The consistent finding that cost stickiness significantly and positively affects R&D investment is a primary contribution of this study. It suggests that managers utilize idle resources, represented by sticky costs due to adjustment cost delays, as a strategic buffer for R&D activities, aligning with rational decision theory. By using these internal resources, managers can maintain or even increase R&D activities, offering a flexible resource allocation strategy when operational activity levels decline. This supports the notion of R&D investment serving as a means to strategically utilise organisational slack in the face of downward adjustments (Chiu & Liaw, 2009). This finding highlights the importance of proactive resource management and strategic cost planning. Hence, managers should have a nuanced understanding of cost behaviour and its strategic utility, instead of resorting to cost-cutting.

Our study shows that managerial overconfidence has a direct positive effect on R&D investment and a consistent negative effect on corporate profitability. This suggests that while overconfidence might lead to decisions that negatively affect financial profitability, it weakens the negative impact of cost stickiness on corporate performance. When facing the negative consequences of cost stickiness, overconfident managers might be willing to take risks and adopt aggressive strategies, thereby reducing the negative impact (Jeon & Ra, 2024). Therefore, boards of directors should consider implementing governmental mechanisms to monitor managerial overconfidence. This ensures that strategic decisions are based on realistic assessments, rather than inflated self-beliefs. Such measures could involve promoting diverse perspectives in decision-making processes and strengthening internal control systems, allowing firms to potentially harness the innovative drive of overconfidence while effectively managing its risks.

Furthermore, the positive impact of financial slack on R&D investment in pooled OLS models, corroborates the internal financing preference within pecking order theory (Leary & Roberts, 2010). This result suggests that internal financial resources are key enablers of R&D investment. Firms with greater liquidity are more capable of funding R&D activities, which entail higher uncertainty compared to other investments. These internal resources provide the necessary flexibility and capacity for R&D initiatives. It is a particularly relevant insight for Japanese firms, which historically have shown a preference for internal financing.

5.3. Contributions and Limitations

This study makes novel contributions to the literature on cost behaviour, innovation, and corporate finance. First, a primary contribution is the initial discovery that cost stickiness encourages investment in R&D. While previous research explored the effects of cost stickiness, this study uniquely investigates its impact on innovation strategies. The quantitative analysis employed in this study, using the Weiss model to measure cost stickiness as an independent variable and incorporating interaction effects, demonstrates its direct influence and moderating effect on R&D investment. This approach provides a robust empirical foundation for understanding cost behaviour. Second, the study offers valuable insights into the drivers of R&D investment, particularly in the context of Japanese firms. By investigating how cost stickiness, optimism, and financial slack influence R&D investment, this study provides evidence on resource allocation for innovation in a unique economic environment.

Despite its contributions, this study has certain limitations that suggest future research directions. First, while this study clarifies the impact of cost stickiness on R&D investment, its direct relationship with corporate performance shows mixed results (non-significant in OLS models, but negative in fixed effect models). Future studies should explore the mechanisms through which cost stickiness might indirectly influence corporate performance, for instance, by examining its long-term effects on innovation or efficiency. Second, while intangible assets positively correlate with performance (representing an innovation output), a direct link between R&D intensity (as an innovation input) and overall corporate performance was not the primary focus and thus not fully explored in this study. Future studies should clearly investigate this correlation, using a broader range of performance indicators, such as return on invested capital (ROIC), or more comprehensive measures derived from Ohlson model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.H. and G.G.; methodology, G.G.; software, S.H.; validation, S.H. and G.G.; formal analysis, G.G.; investigation, G.G.; resources, S.H.; data curation, G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.; writing—review and editing, S.H.; visualisation, G.G.; supervision, S.H.; project administration, S.H.; funding acquisition, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI under Grant number 23K01700.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| R&D | Research and development |

| SG&A | Selling, general, and administrative (expenses) |

| OLS | Ordinary least squares |

| RBV | Resource based view |

| ROA | Return on assets |

| GAAP | Generally accepted accounting principles |

| M&A | Mergers and acquisitions |

| JSPS | Japan society for the promotion of science |

| ROIC | Return on invested capital |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

References

- Anderson, M. C., Banker, R. D., & Janakiraman, S. N. (2003). Are selling, general, and administrative costs “sticky”? Journal of Accounting Research, 41(1), 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwin, A. S., Krishnan, R. T., & George, R. (2016). Board characteristics, financial slack and R&D investments: An empirical analysis of the Indian pharmaceutical industry. International Studies of Management and Organization, 46(1), 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, R., & Gruca, T. S. (2008). Cost stickiness and core competency: A note. Contemporary Accounting Research, 25(4), 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, R., Petersen, M. J., & Soderstrom, N. S. (2004). Does capacity utilization affect the “stickiness” of cost? Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 19(3), 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R. D., & Byzalov, D. (2014). Asymmetric cost behavior. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 26(2), 43–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R. D., Byzalov, D., & Chen, L. T. (2013). Employment protection legislation, adjustment costs and cross-country differences in cost behavior. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 55(1), 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R. D., Byzalov, D., Ciftci, M., & Mashruwala, R. (2014a). The moderating effect of prior sales changes on asymmetric cost behavior. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 26(2), 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R. D., Byzalov, D., & Plehn-Dujowich, J. M. (2014b). Demand uncertainty and cost behavior. The Accounting Review, 89(3), 839–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R. D., Flasher, R., & Zhang, D. (2025). Strategic positioning and asymmetric cost behavior. Asian Review of Accounting, 33(1), 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basgoze, P., & Sayin, C. (2013). The effect of R&D expenditure (investment) on firm value: Case of Istanbul Stock Exchange Turkey. Journal of Business Economics and Finance, 2(3), 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Beladi, H., Deng, J., & Hu, M. (2021). Cash flow uncertainty, financial constraints and R&D investment. International Review of Financial Analysis, 76, 101785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, T., & Schnippering, M. (2022). Corporate social and financial performance: Revisiting the role of innovation. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(3), 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, J. N. (2014). Determinants of “sticky costs”: An analysis of cost behavior using United States air transportation industry data. The Accounting Review, 89(5), 1645–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. X., Lu, H., & Sougiannis, T. (2012). The agency problem, corporate governance, and the asymmetrical behavior of selling, general, and administrative costs. Contemporary Accounting Research, 29(1), 252–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. X., Nasev, J., & Wu, S. Y.-C. (2022). CFO overconfidence and cost behavior. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 34(2), 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-C., & Liaw, Y.-C. (2009). Organizational slack: Is more or less better? Journal of Organizational Change Management, 22(3), 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftci, M., & Salama, F. M. (2018). Stickiness in costs and voluntary disclosures: Evidence from management earnings forecasts. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 30(3), 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collis, D. J., & Montgomery, C. A. (2005). Corporate strategy: A resource-based approach. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M. D., & Habib, A. (2023). Cost stickiness and firm value. Journal of Management Control, 34(2), 235–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, A., Verbeek, M., & Verwijmeren, P. (2012). Does financial flexibility reduce investment distortions? Journal of Financial Research, 35(2), 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, F., & Presti, C. (2018). The relationship between intellectual capital and big data: A review. Meditari Accountancy Research, 26(3), 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukas, J. A., & Petmezas, D. (2007). Acquisitions, overconfident managers and self-attribution bias. European Financial Management, 13(3), 531–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, S. I. (2018). Companies’ financial surpluses and cash/deposit holdings. Public Policy Review, 14(3), 369–396. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, S. W., & Makri, M. (2006). Exploration and exploitation innovation process: The role of organizational slack in R&D intensive firms. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 17(1), 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G. (2005). Slack resources and the performance of privately held firms. Academy of Management Journal, 48(4), 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, S., Heaton, J. B., & Odean, T. (2011). Overconfidence, compensation contracts, and capital budgeting. The Journal of Finance, 66(5), 1735–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisetti, C., & Pontoni, F. (2015). Investigating policy and R&D effects on environmental innovation: A meta-analysis. Ecological Economics, 118, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gral, B., & Gral, B. (2014). Conclusion and forecast. In How financial slack affects corporate performance: An examination in an uncertain and resource scarce environment (pp. 105–108). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gruener, A., & Raastad, I. (2018). Financial slack and firm performance during economic downturn. GSL Journal of Business Management and Administrative Affairs, 1(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar]