Abstract

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) are increasingly positioned as digital equivalents to physical cash, yet their ability to replicate the full functionality of cash remains contested. This study investigates whether the proposed Digital Euro can credibly serve as a substitute for physical Euro cash. Using a qualitative comparative framework, the analysis evaluates both currencies using 36 pairwise comparisons. The findings reveal that while the Digital Euro offers advantages in portability, divisibility, and digital integration, it falls short in key areas such as anonymity, fungibility, recognizability, and universal acceptability. These limitations are primarily due to technological dependencies, regulatory constraints, and the absence of physical tangibility. The study concludes that the Digital Euro cannot fully mimic the role of physical cash, particularly in offline and privacy-sensitive contexts. As a result, the hypothesis that the Digital Euro is an electronic equivalent of physical Euro cash is rejected. These findings underscore the continued relevance of physical currency and highlight the need for cautious, evidence-based CBDC design and implementation.

Keywords:

central bank digital currency (CBDC); digital euro; currency; money; legal tender; quality 1. Introduction

The advent of digital currencies marks a significant evolution in the financial landscape, reflecting the rapid technological advancements shaping modern economies. Central banks worldwide are exploring the potential of digital currencies, with the European Central Bank (ECB) at the forefront, introducing the concept of the Digital Euro. This initiative aims to create a digital counterpart to the physical Euro, promising to retain the intrinsic qualities of cash while leveraging the benefits of digital technology.

A growing body of literature has examined Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) from macroeconomic, regulatory, and technological perspectives. Auer and Böhme (2020a, 2021) developed an influential taxonomy of CBDC design choices, emphasizing trade-offs between privacy, efficiency, and security. Their research highlights that achieving the anonymity of cash in a digital format is particularly challenging, with most proposals offering only pseudonymity or requiring identity-verification mechanisms. Bindseil et al. (2021) focused on the ECB’s design options for a Digital Euro, highlighting the risks of bank disintermediation and emphasizing the necessity of holding limits and non-remuneration features. Similarly, Mancini Griffoli et al. (2018) explored hybrid and synthetic CBDC models, calling attention to institutional trade-offs between innovation and central bank control.

Research from Lee et al. (2021, 2023) contributed important empirical and conceptual insights, especially around the challenges of achieving functional equivalence between digital and physical money. These studies suggest that CBDCs may struggle to match the universality, recognizability, and trustworthiness of cash, particularly in populations with limited digital literacy or access. Meanwhile, scholars like Schueffel (2023) and Salampasis et al. (2023) have examined the broader socio-technical context of digital finance, emphasizing how CBDCs intersect with themes of digital sovereignty, user autonomy, and systemic trust. Additional contributions from the IMF (2020), BIS (2021) and the Bank of Canada et al. (2020) have explored the policy implications of CBDCs, often through the lens of financial stability, inclusion, and innovation.

While these works offer valuable perspectives, few provide a structured, comparative analysis that evaluates the Digital Euro and physical Euro side by side using classical monetary functions and well-established frameworks of quality. Most existing assessments remain conceptual or speculative, especially given the Digital Euro’s developmental status. The literature lacks a methodologically grounded instrument that can systematically evaluate the Digital Euro’s strengths and weaknesses across both practical and experiential dimensions. The ECB posits that the Digital Euro will be akin to cash, serving as an electronic means of payment that is available to the general public and backed by the central bank in the same manner as physical banknotes and coins. According to the ECB, a Digital Euro would be an electronic means of payment: “It would be a digital version of cash, available to the general public and backed by the European Central Bank the same way your physical banknotes and coins are. You could use it anywhere that you already use physical euro cash” (European Commission, 2023). This CBDC is envisioned as a universally accessible form of digital cash, designed for seamless use across all digital payment platforms within the Euro area (ECB, 2023b).

The proposed Digital Euro aims to replicate the physical Euro’s function as a stable, secure, and widely accepted medium of exchange: “Essentially, the digital euro will serve as a digital version of physical euro notes and coins” (Euronews, 2023). By being issued by the Eurosystem, the ECB, and related parties, the Digital Euro will maintain the trust and credibility associated with physical currency. The ECB underscores this by stating, “Like the physical euro, a digital version would be issued by Eurosystem—the ECB and the national banks of countries in the euro area” (Pladson, 2021).

In its design, the Digital Euro is intended to be used for all digital payments throughout the euro area, enhancing the ease and efficiency of transactions (ECB, 2023c). This digital currency would allow Europeans to utilize public money for digital payments in the same way they use cash for physical transactions, thus bridging the gap between traditional and modern forms of currency (ECB, 2023d).

Furthermore, the ECB emphasizes that the Digital Euro would be just as accessible and usable as cash, ensuring its availability to everyone within the euro area (ECB, 2023c). This universal accessibility is crucial for fostering financial inclusion and ensuring that all citizens can benefit from the advantages of digital currency (ECB, 2023d).

Despite these claims, a significant research gap remains regarding whether a CBDC such as the Digital Euro can truly fulfill the practical, social, and qualitative functions that physical cash has long embodied, especially in terms of offline usability, anonymity, fungibility, and universal acceptance. While the ECB and related institutions emphasize technological innovation and financial inclusion, there has been insufficient critical scrutiny of whether digital currency can serve as a functional and qualitative equivalent to cash in real-world settings. This paper seeks to fill that gap. Accordingly, this study poses the guiding research question: Can the Digital Euro serve as a functional and qualitative equivalent to physical Euro cash, when evaluated against the characteristics of money and the dimensions of quality? From this research question, follow the hypotheses underpinning this study: The null hypothesis suggests that the Digital Euro is an electronic equivalent of physical Euro cash in terms of the characteristics of money and the dimensions of quality. Consequently, the alternative hypothesis posits that the Digital Euro is not an electronic equivalent of physical Euro cash in terms of the characteristics of money and the dimensions of quality.

In addition to its economic and monetary implications, the Digital Euro is also deeply relevant to the broader fields of blockchain and distributed ledger technology (DLT) research. Although the European Central Bank has not committed to deploying the Digital Euro on a blockchain infrastructure, its conceptual foundation draws heavily from the design logic of digital assets and permissioned DLT systems (Allen et al., 2020; Auer & Böhme, 2020b; Sbírneciu & Valentina Florea, 2023). As such, the Digital Euro represents a policy-driven response to the rise of decentralized cryptocurrencies and stablecoins, prompting renewed debates around digital sovereignty, programmability, and the role of central banks in the digital asset ecosystem (Aneja & Dygas, 2022; Auer et al., 2023; Bindseil et al., 2021; Mancini Griffoli et al., 2018). Moreover, its development is embedded within a rapidly evolving regulatory environment across the European Union, where initiatives such as the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA) are shaping the legal and compliance frameworks for both public and private digital currencies (Minto, 2025; Sbírneciu & Valentina Florea, 2023; van der Linden & Shirazi, 2023). This paper contributes to these intersecting domains by critically evaluating whether a CBDC like the Digital Euro can truly replicate the functional and qualitative attributes of physical cash. It thereby advances both design considerations and regulatory discourse in the digital currency landscape.

In pursuit of the research question stated above, the study draws a clear conceptual distinction between money and currency. For this reason, a conceptual distinction is made between money and currency in this paper. Money refers to the abstract, functional concept in economics that fulfills roles such as medium of exchange, unit of account, store of value, and standard of deferred payment. Currency, by contrast, is the physical or digital form that money takes, its tangible or recordable representation used in everyday transactions. Accordingly, this study does not compare two forms of money per se, but rather two currencies—the physical Euro (i.e., coins and banknotes) and the proposed Digital Euro (a CBDC)—which is intended to serve as a token of the same monetary unit. Both are planned to accomplish the same monetary functions, but their performance as currencies may differ depending on technological, legal, and practical attributes. Previous research has cast doubt on the perfect substitutability of retail CBDCs and central bank money, such as physical cash (Lee et al., 2021, 2023; McNulty et al., 2024; Milne, 2024; Schueffel, 2023). This article, therefore assesses the ECB’s claims by examining the Digital Euro and the physical euro through the lens of the fundamental characteristics of money and Garvin’s dimensions of quality (Garvin, 1987).

Such an assessment along the characteristics of money, as well as the dimensions of quality, will provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating the comparative advantages and potential challenges associated with the Digital Euro. By exploring these facets, this research aims to provide a thorough analysis of whether the Digital Euro can indeed match the efficacy and quality of its physical counterpart. This critical examination of the Digital Euro takes place against a broader, evolving financial backdrop marked by a fundamental tension between traditional government control over money and the burgeoning ideals of decentralized finance (DeFi) (Schueffel, 2025), a struggle which increasingly influences economic policies and individual financial choices (Tommerdahl, 2025).

Beyond retail payments, CBDCs are increasingly seen as strategic tools for broader policy objectives, including financial stability and climate risk integration. Proposals have suggested using permissioned DLT networks among central banks to settle cross-border transactions and price in systemic risks. Projects such as Singapore’s Project Ubin and the Utility Settlement Coin in Europe demonstrate the potential of such infrastructure. While the Digital Euro is not currently designed for these purposes, it must be viewed within the wider shift toward programmable, policy-aligned monetary systems (Chen, 2018).

2. Background

In order to conduct the aforementioned analysis comparing the Digital Euro to the physical Euro by applying the characteristics of money as well as the dimensions of quality, the following paragraphs will provide a detailed overview of the criteria used: the characteristics of money as described in the extant body of literature and the dimensions of quality as defined by Garvin (1987).

2.1. Money

Money evolved from barter systems to commodity money (gold, silver) and later to representative money (banknotes). Money encompasses all accepted mediums of exchange, while currency specifically refers to physical or digital forms used in transactions (Davies, 2010; Ferguson, 2008). In the following paragraphs, a definition of money is provided along with its core functions and supplementary characteristics.

2.1.1. Definition of Money

Money is fundamentally a social and legal construct that functions as a universally accepted means of economic exchange. It fulfills four core functions: medium of exchange, unit of account, store of value, and standard of deferred payment (Mishkin, 2022). These functions are realized through various physical or digital instruments, known as currencies.

While the terms money and currency are sometimes used interchangeably, this paper maintains a crucial distinction: Money refers to the abstract concept that embodies the functions outlined above. Currency, however, refers to the physical or digital tokens used to represent money in practice, such as coins, banknotes, or Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) (Mankiw, 2021; Rogoff, 2016). Thus, while all currency can be considered money, not all money takes the form of currency, underscoring the evolving nature of money in an increasingly digital economy (Arestis & Sawyer, 2005). However, as a minimum requirement, all currencies ought to fulfill the functions and qualities of money.

In this study, both the physical Euro and the Digital Euro are understood as currencies, i.e., forms of money issued by the European Central Bank (ECB). The focus, therefore, lies in comparing these two currencies in terms of their effectiveness at realizing the functions and characteristics expected of money.

By evaluating the currencies through this lens, this study provides a grounded framework for assessing whether the Digital Euro can credibly perform the role that physical cash has long fulfilled in the Eurozone.

2.1.2. Characteristics of Money

Money is an essential construct in facilitating economic activity, acting as a medium through which goods and services can be exchanged, values stored, and financial stability maintained across different economic contexts. Its utility is derived from a series of inherent functions and characteristics, each supported by a substantial body of economic theory and empirical evidence. They are the following ones, starting with the four core functions (i) Medium of Exchange, (ii) Unit of Account, (iii) Store of Value, and (iv) Standard of Deferred Payment (Mishkin, 2022). These four functions and characteristics are supplemented by the following eight: (1) Divisibility, (2) Portability, (3) Durability, (4) Fungibility, (5) Recognizability, (6) Scarcity, (7) Acceptability, and (8) Legal Tender (Mankiw, 2021). These functions and characteristics are described in more detail in the next paragraphs, beginning with the four core functions.

- Core Functions

The core functions and characteristics money has to fulfill are the following ones.

- (i)

- Medium of Exchange

Money’s primary role as a medium of exchange addresses the inefficiencies inherent in barter systems, notably the requirement for a double coincidence of wants. By acting as a common intermediary, money facilitates transactions and enhances economic efficiency (Jevons, 1875; Samuelson, 1958).

- (ii)

- Unit of Account

Money serves as a unit of account, providing a standard measure of value that simplifies the process of pricing goods and services. This function allows for a coherent system of economic calculation, necessary for comparing the worth of various commodities and services within and across markets (Menger, 1892; Walras, 1874/1988).

- (iii)

- Store of Value

As a store of value, money allows economic agents to transfer purchasing power from the present to the future. This characteristic is vital for the functioning of modern economies, supporting savings and investment decisions (Keynes, 1930; Ricardo, 1817). Mill (1849) posits that the stability of money’s value is crucial in determining its effectiveness as a store of value.

- (iv)

- Standard of Deferred Payment

Money as a standard of deferred payment is integral to the operation of credit markets, where future payments are predicated on money retaining stable value over time (Marx, 1887; Schumpeter, 1934). This function of money underpins various forms of credit agreements and financial instruments, facilitating economic activities that require long-term financial planning and execution.

- Supplementary Characteristics

Money’s efficacy as a cornerstone of economic activity is underpinned not only by its primary functions but also by several intrinsic characteristics that ensure its practical usability and effectiveness in various economic contexts. These characteristics are crucial for money to fulfill its roles comprehensively.

- (1)

- Divisibility

Divisibility refers to money’s ability to be broken down into smaller units, facilitating transactions of varying sizes and values (Menger, 1892; Samuelson & Nordhaus, 1998).

- (2)

- Portability

Portability implies that money can be easily carried and transferred between parties. This feature is crucial for money to function efficiently as a medium of exchange across different locations (Friedman, 1956; Mishkin, 2022).

- (3)

- Durability

Durability means that money can withstand physical wear and tear and the passage of time without degrading in value or usability. It ensures that it can serve as a store of value and standard of deferred payment over long periods of time (Keynes, 1930; Tobin, 1965).

- (4)

- Fungibility

Fungibility denotes money’s interchangeability, where each unit is identical and can be substituted with another unit of the same value. This attribute simplifies transactions, pricing, and accounting, as each unit is accepted (Goodhart, 1989; Menger, 1892).

- (5)

- Recognizability

Recognizability refers to the ease with which money can be identified and authenticated. This characteristic minimizes the risk of counterfeiting and fraud, thus preserving trust in the monetary system (Ricardo, 1817; Smith, 1776).

- (6)

- Scarcity

Scarcity ensures that money is not overly abundant, maintaining its value over time. If money were not scarce, it would lose its effectiveness as a store of value due to inflation or hyperinflation (Friedman, 1956; Keynes, 1930).

- (7)

- Acceptability

Acceptability means that money must be widely accepted by all parties within an economy for all types of transactions. This widespread acceptance is crucial for money to function effectively as a medium of exchange (Mishkin, 2022; Samuelson & Nordhaus, 1998).

- (8)

- Legal Tender

Legal tender refers to money that must be accepted if offered in payment of a debt. The legal status of money provides it with the authority and backing of the government, mandating its acceptance (Hicks, 1989; Keynes, 1930).

These attributes ensure that money effectively performs its functions across different economic situations, from daily transactions to long-term financial planning. The development of digital currencies, such as the Digital Euro, seeks to replicate these attributes in a form that aligns with the digitalization of modern economies, thus necessitating a rigorous examination of how these digital forms compare to traditional physical currencies in fulfilling the established roles of money.

2.2. Quality

Within the business domain, quality emerged as a complex construct inextricably linked to both product and service offerings. It signifies the extent to which these offerings fulfill, or surpass, the established expectations of the customer base. While historically rooted in the practices of skilled craftspeople, the conceptualization of quality underwent a significant transformation during the Industrial Revolution. Quality became thus a cornerstone of competitive advantage within the contemporary marketplace (Crosby, 1979; Deming, 2018; Feigenbaum, 1991; Juran & De Feo, 2010).

Definition of Quality

The term “quality” encompasses a variety of interpretations and dimensions, making it a multifaceted concept in both academic and practical contexts. Quality generally refers to the degree to which a product or service meets certain standards or satisfies specific requirements. Various definitions highlight different aspects of quality, depending on the context and the criteria used for evaluation.

One of the seminal definitions of quality is provided by Garvin (1987), who identified various major approaches to understanding and measuring quality: transcendent, product-based, user-based, manufacturing-based, and value-based. According to Garvin, the transcendent approach views quality as an inherent characteristic, often synonymous with excellence and universally recognizable. The product-based approach considers quality as a precise and measurable variable, often focusing on the quantity of a desired attribute. The user-based approach defines quality in terms of the satisfaction it provides to the consumer, emphasizing personal preferences and individual experiences. The manufacturing-based approach associates quality with conformance to specifications and the absence of defects, highlighting consistency and reliability in production. Finally, the value-based approach balances quality with cost, suggesting that the best quality is the one that provides the most benefit for the price.

While the concept of quality can be defined and interpreted in various ways, Garvin’s (1987) framework provides a comprehensive understanding by categorizing different perspectives and approaches. This multifaceted view is essential for addressing quality in diverse fields, ensuring that products and services meet or exceed expectations across different dimensions.

- Dimensions of Quality

Garvin (1987) identified eight dimensions that capture the multifaceted nature of product and service quality. These dimensions provide a systematic framework for evaluating how well an offering meets customer expectations across technical, functional, and experiential domains. While Garvin’s model was developed primarily for manufactured goods, several of its elements have proven adaptable to other fields, including services (Ighomereho et al., 2022; Parasuraman et al., 1985). In this study, a subset of these dimensions is applied to evaluate the comparative quality of physical and digital currencies.

Given the distinct nature of central bank-issued currencies, particularly those functioning as public goods enabling certain services rather than private commodities, not all of Garvin’s dimensions are equally applicable. After careful consideration, four dimensions were selected for their conceptual relevance and suitability for evaluating currency performance: performance, reliability, perceived quality, and durability. The remaining four dimensions—features, conformance, serviceability, and esthetics—were excluded due to their limited applicability in this specific context.

- (a)

- Performance

Performance refers to the currency’s capacity to fulfill its intended purpose under real-world conditions. In the context of money, this includes the speed and ease of completing transactions, cross-environment usability (e.g., online and offline), and overall efficiency. As Garvin (1987) and Juran and De Feo (2010), emphasize, performance is a primary determinant of utility and user satisfaction. Applied to currencies, it captures the extent to which a currency enables smooth, effective exchange in a modern economic setting.

- (b)

- Reliability

Reliability addresses the consistency and predictability with which a currency performs its functions over time. A reliable currency does not “fail” in practical use, whether through technological outages in a digital system or degradation of physical banknotes in circulation. As noted by Parasuraman et al. (1985), reliability is a cornerstone of perceived service quality and plays a critical role in maintaining user trust.

- (c)

- Perceived Quality

Perceived Quality captures the subjective assessment that users form about a currency’s trustworthiness, ease of use, and legitimacy. Unlike performance or reliability, which can be observed directly, perceived quality is influenced by reputation, institutional backing, and prior experience (Zeithaml, 1988). Garvin (1987) highlights that perceived quality can powerfully shape user behavior even when technical performance is equal among alternatives.

- (d)

- Durability

Durability, traditionally applied to physical goods, is here understood in dual terms: the physical resilience of banknotes and coins, and the robustness of the digital infrastructure supporting the Digital Euro. As Gale and Wood (1994) argue, durability enhances long-term value and reduces the need for frequent replacement. In the context of money, a durable form must resist degradation (physical) or systemic failure (digital) across repeated uses.

As mentioned afore certain characteristics of quality suggested by Garvin (1987) were omitted from the assessment: features defined by Garvin as supplementary characteristics beyond core functionality were excluded due to the ambiguous nature of “added features” in a sovereign currency. While the Digital Euro may include programmable capabilities, these are not universally available or clearly defined in ECB documentation, and thus difficult to evaluate in a standardized manner. Other dimensions included in Garvin’s (1987) framework were not included in the assessment as they are unsuitable services enabling public goods: conformance, which measures adherence to predefined standards, was deemed unsuitable. Serviceability, which reflects the ease of maintenance and repair, was also not applicable to either form of currency. Lastly, esthetics, while relevant to tangible consumer products, plays no meaningful role in evaluating a currency’s effectiveness. In summary, this study applies only those dimensions from Garvin’s model that align with the nature of central bank currencies as infrastructure-like public goods. The selected dimensions., i.e., performance dimensions, reliability, durability, and perceived quality, allow for a balanced and relevant comparison of the physical and digital Euro, while avoiding criteria that would introduce conceptual misfit or bias.

Based on the distinction established between money and currency, this study does not ask whether the Digital Euro and physical Euro represent different forms of money. Rather, it examines whether these two currencies, both representations of the Euro as a unit of account, perform differently in fulfilling the established characteristics and functions associated with money.

The guiding research question—“Can the Digital Euro serve as a functional and qualitative equivalent to physical Euro cash as a currency?” is therefore: evaluated against the afore mentioned characteristics of money and dimensions of currency quality.

This question challenges the ECB’s repeated assertions that the Digital Euro would act as a “digital version of cash.” Accordingly, the null hypothesis to be tested is:

H0:

The Digital Euro is an electronic equivalent of physical Euro cash in terms of the characteristics of money and the dimensions of quality.

As the alternative hypothesis then follows:

H1:

The Digital Euro is not an electronic equivalent of physical Euro cash in terms of the characteristics of money and the dimensions of quality.

This comparison does not assume that one currency is inherently “better” than the other in all contexts but instead evaluates whether the Digital Euro can fulfill the same roles and expectations as physical cash.

Understanding whether the Digital Euro can truly serve as an equivalent to Euro cash is crucial for various stakeholders. For consumers, it directly impacts their trust in and adaptability to new digital payment methods, which influences everyday financial activities and savings behavior. Policymakers need clear insights to make informed decisions on regulatory frameworks and to assess the socio-economic implications, including financial stability and inclusion. For financial institutions, the equivalence between digital and physical cash will affect strategic planning, risk management, and the development of new financial services and products that cater to evolving consumer needs and technological advancements.

3. Materials and Methods

This study applies a qualitative comparative methodology to assess whether the proposed Digital Euro can credibly replicate the physical Euro in its role as a currency. While both the physical and digital versions represent the same monetary unit issued by the European Central Bank, their forms differ fundamentally: one being tangible and analog, the other intangible and technologically mediated. The core objective is to evaluate whether these two currencies differ in their ability to deliver the practical characteristics expected of money in daily economic life.

Given the absence of real-world usage data for the Digital Euro, a qualitative approach was not only chosen but also necessitated. The currency is still in the design and consultation phase, and most of the technical, legal, and operational details remain speculative or only partially disclosed. As such, quantitative comparisons based on empirical transaction data are not yet feasible. Instead, this study relies on conceptual reasoning supported by policy documentation, central bank literature, academic sources, and comparative insights from other CBDC implementations such as the Chinese e-CNY. The use of qualitative methodology allows for a contextualized, structured, and multidimensional evaluation of two different currency formats, grounded in normative expectations and institutional design logic.

In addition, qualitative research is particularly well-suited for this study as it enables the examination of complex phenomena within their real-world context. According to Creswell and Poth (2016), qualitative research is an effective method for exploring intricate processes, meanings, and experiences. This approach allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data that can provide insights into the multifaceted nature of currency usage and acceptance. Furthermore, the use of qualitative methods aligns with previous studies on digital currencies and financial systems, which often employ similar methodologies to uncover the nuanced dynamics at play (Miles et al., 2014; Patton, 2014).

The analysis is built on a matrix structure that combines two sets of evaluative criteria. The first axis consists of the subset of three relevant dimensions of quality according to Garvin (1987): Performance, Reliability, and Perceived Quality. The dimension of Performance is used here to assess how effectively a currency fulfills its intended operational role under realistic use conditions. Reliability captures the consistency and dependability of the currency over time and across settings. Finally, Perceived Quality reflects users’ subjective impressions of legitimacy, trustworthiness, and comfort in using the currency attributes essential for widespread acceptance. To avoid conceptual overlap, the quality dimension of durability was excluded from the horizontal axis of the matrix, as it is represented among the attributes of money. This step prevents double-counting and preserves the integrity of the framework.

The vertical axis draws on the afore mentioned four core attributes of money, Medium of Exchange, Unit of Account, Store of Value, and Standard of Deferred Payment as well as the aforementioned supplementary attributes of money, Divisibility, Portability, Durability, Fungibility, Recognizability, Scarcity, Acceptability, and Legal Tender.

The evaluation is guided by documented ECB proposals, technical design papers, published CBDC frameworks, and relevant economic literature.

The resulting matrix contains thirty-six pairwise comparisons, with each cell evaluating how the Digital Euro and the physical Euro perform in relation to one of the twelve monetary characteristics under a specific quality dimension.

The strength of this methodology lies in its ability to offer a structured and transparent evaluation despite the absence of empirical usage data. However, several limitations are acknowledged. All dimensions and characteristics are weighted equally, although in practice, users may value some traits (e.g., privacy or offline usability) more than others. Furthermore, the qualitative judgments rely on anticipated design features of the Digital Euro, which may evolve or diverge from current proposals during actual implementation. Despite these caveats, this methodological design enables a systematic and conceptually grounded inquiry into whether the Digital Euro can live up to the benchmark set by physical cash.

Table 1 schematically shows the procedure for the pairwise evaluation of both currencies.

Table 1.

Quality of Money Matrix.

The data utilized in this paper stem from a diverse array of contemporary sources, blending theoretical, empirical, and policy-oriented perspectives. Policy and technical insights on CBDCs in general and the Digital Euro in particular are drawn extensively from reports by the BIS (2021) and the ECB (2020, 2023a), offering a comprehensive analysis of their design, implications, and adoption readiness. Furthermore, practical case studies and statistical insights from Deutsche Bundesbank (2024) and Eurostat (2024) supplement the analysis with empirical depth. This combination of data-driven resources ensures a well-rounded qualitative examination of the topic, integrating perspectives from academic literature, institutional reports, and empirical data.

4. Results

Both types of money, the physical Euro and the Digital Euro are compared using each field of the above-derived “Quality of Money Matrix”. Hence, the comparison starts with the money quality “Performance” and goes step-by-step down the first column along the twelve attributes “i. Medium of Exchange”, “ii. Unit of Account”, and “iii. Store of Value” down to “8. Legal Tender”. Subsequently the same procedure is executed for the columns “Reliability” and “Perceived Quality”. Altogether, 36 qualitative comparisons are carried out pairwise. They are the following ones.

4.1. Performance

- Medium of Exchange

Physical Euro: The physical Euro is established as a highly effective medium of exchange, primarily due to its tangible nature which allows for immediate transactions. Its wide acceptance across the Eurozone is underpinned by the legal mandates that enforce its use in all cash transactions, promoting economic stability and trust among consumers and businesses (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro aims to enhance transaction speed and reduce geographical limitations. Its performance as a medium of exchange could potentially surpass that of physical currency by offering real-time transactions globally, contingent on internet access (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020).

The digital Euro’s potential to enable real-time, global transactions surpasses the physical Euro’s immediacy in face-to-face exchanges, granting it an edge as a medium of exchange.

Qualitative verdict: “+” Digital Euro performs better than physical Euro.

- Unit of Account

Physical Euro: As a unit of account, the physical Euro provides a stable measure for pricing goods and services, facilitating coherent and consistent financial accounting across the Eurozone. This stability is crucial for maintaining economic order and supporting fiscal policies (ECB, 2020; European Commission, 2023; Eurostat, 2024).

Digital Euro: The proposed digital Euro is expected to maintain these attributes while offering enhanced features such as improved traceability and easier integration into digital accounting systems, potentially increasing transparency and efficiency in economic transactions (ECB, 2020, 2023c; IMF, 2020).

Both the physical and digital Euro perform effectively as units of account, with the physical Euro providing stability and the digital Euro offering potential enhancements in transparency and digital integration, making them equally reliable in this role.

Qualitative verdict: “0” Digital Euro and physical Euro perform equally well.

- Store of Value

Physical Euro: The ECB aims to maintain price stability by targeting an inflation rate of 2% over the medium term. This target is considered optimal for fostering economic growth and preventing deflation. Consequently, the physical Euro is subject to this inflation (ECB, 2024d).

Digital Euro: The Digital Euro, as proposed by the ECB, is intended to maintain parity in value with the physical Euro. Consequently, it would be subject to the same inflation dynamics as the traditional Euro. However, the ECB has indicated that the digital euro would not accrue interest, meaning it would neither earn positive interest nor be subject to negative interest rates Yet, the theoretical framework of CBDCs includes the potential for negative interest rates, offering central banks new avenues for implementing monetary policy (Bindseil & Panetta, 2020).

The physical Euro’s established role as a store of value, combined with its use in conventional monetary systems, currently provides greater reliability compared to the digital Euro, which introduces uncertainties like potential negative interest rates in its theoretical framework.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Standard of Deferred Payment

Physical Euro: The physical Euro is widely recognized and accepted for deferred payments, supported by an extensive legal framework that guarantees its use for settling debts. This established trust makes it a cornerstone of financial agreements within and across Eurozone countries (ECB, 2020; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: While still under development, the digital Euro’s performance in this area will heavily depend on its acceptance and the trust it garners from the public and businesses. If successfully integrated, it could offer more flexible and efficient deferred payment options (ECB, 2020).

Weighing the existing physical Euro as a trusted standard of deferred payment against the potential, yet hypothetical performance of a Digital Euro in this function, both are estimated equal.

The physical Euro’s established trust and legal framework for deferred payments are matched by the digital Euro’s potential to offer flexibility and efficiency if successfully integrated, making them equally reliable for this function.

Qualitative verdict: “0” Digital Euro and physical Euro perform equally well.

- Divisibility

Physical Euro: The physical Euro’s divisibility is an essential feature, allowing it to be broken down into smaller denominations for precise transactions. Coins and banknotes in various denominations facilitate everyday purchases and financial operations, ensuring the currency’s usability for transactions of all sizes down to one Euro cent amounts (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro promises enhanced divisibility, with the potential for even smaller units than physical coins and notes. This can benefit microtransactions and online purchases, providing greater flexibility and precision in financial transactions (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2021; IMF, 2020).

The digital Euro’s ability to support smaller units than the physical Euro allows for greater flexibility and precision in transactions, especially for microtransactions, making it superior in divisibility.

Qualitative verdict: “+” Digital Euro performs better than physical Euro.

- Portability

Physical Euro: Physical Euros, including coins and banknotes, are portable, allowing individuals to carry money for transactions. However, they are limited by the physical bulk and security concerns associated with carrying large amounts of cash (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; Eurostat, 2024).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro significantly enhances portability by enabling users to store and transfer money via digital devices. This reduces the physical burden and risks associated with carrying cash and allows for instant transactions regardless of location (ECB, 2020; IMF, 2020).

When comparing the physical Euro and the digital Euro, the digital Euro’s ability to eliminate the physical limitations of cash and facilitate instant, secure transactions gives it a clear advantage in terms of portability.

Qualitative verdict: “+” Digital Euro performs better than physical Euro.

- Durability

Physical Euro: The durability of physical Euros varies; coins are highly durable, while banknotes, despite being designed to withstand wear and tear, eventually degrade and require replacement (ECB, 2020, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; Eurostat, 2024).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro offers superior durability as it is not subject to physical wear. Digital storage and transfer eliminate the need for physical handling, ensuring longevity and reducing the costs associated with producing and replacing physical money. Yet, the Digital Euro depends on an electronic infrastructure, making it more susceptible to risks that large-scale IT infrastructures are subjected to (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020, 2023d; IMF, 2020).

When evaluating durability, the physical Euro’s susceptibility to wear is balanced by the digital Euro’s reliance on IT infrastructure, making both forms of currency comparable in this regard.

Qualitative verdict: “0” Digital Euro and physical Euro perform equally well.

- Fungibility

Physical Euro: The physical Euro is highly fungible; any single Euro coin or note is interchangeable with another of the same denomination, allowing for consistent value in transactions (ECB, 2020, 2024a; European Commission, 2023).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro aims to maintain fungibility by ensuring that each unit of digital currency is equivalent and interchangeable with another. This will be crucial for its acceptance and usability in financial transactions (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020; IMF, 2020). However, persons holding the Digital Euro will not be anonymous and any money transfer via the Digital Euro will be subject to KYC and AML checks (Bindseil et al., 2021; ECB, 2023a). In addition, there will be a holding cap on the amount of Digital Euros a person can hold in his or her wallet, which is currently envisioned to be somewhere between 1500.- and 3000.-Euros (Bidder et al., 2024; Bindseil & Panetta, 2020; ECB, 2024c; Lambert et al., 2023). In a ceteris paribus comparison it becomes obvious that the Digital Euro can be used in fewer transactions and thus will not reach the fungibility of the physical Euro.

While the digital Euro aspires to achieve full fungibility, the physical Euro’s established universal acceptance and consistent value in transactions currently make it the superior option.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Recognizability

Physical Euro: Physical Euros are easily recognizable by their distinctive designs, security features, and widespread use, facilitating trust and acceptance in transactions (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro’s recognizability will depend on its integration into existing financial systems and user interfaces. Effective digital design and widespread adoption will help to ensure it is as easily recognizable and trusted as the physical Euro (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020). Yet, it will likely take years to accomplish this.

The physical Euro’s established designs and widespread familiarity ensure immediate recognizability, whereas the digital Euro will require time and integration to achieve similar trust and acceptance.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Scarcity

Physical Euro: The physical Euro’s supply is controlled by the European Central Bank, ensuring its scarcity and value. This controlled supply helps maintain economic stability and trust in the currency (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro will also have controlled issuance by the European Central Bank, ensuring its scarcity and preventing inflationary pressures. Its digital nature allows for precise management of supply and demand (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020; IMF, 2020).

Both the physical and digital Euro benefit from the European Central Bank’s controlled issuance, ensuring scarcity and maintaining trust and economic stability, making them equally effective in this regard.

Qualitative verdict: “0” Digital Euro and physical Euro perform equally well.

- Acceptability

Physical Euro: The physical Euro is widely accepted for all transactions within the Eurozone, supported by legal mandates and public trust, making it a reliable medium of exchange (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro aims to achieve similar acceptability by integrating with digital payment systems and gaining regulatory and public trust (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020). However, most likely Digital Euro wallets will have holding limits somewhere between 1500.- and 3000.- Euros (Bidder et al., 2024; Bindseil & Panetta, 2020; ECB, 2024c; Lambert et al., 2023). This would automatically exclude Digital Euro payments in certain settings.

The physical Euro’s universal acceptance, backed by legal mandates, contrasts with the potential limitations of the digital Euro, such as wallet holding caps, which may restrict its usability in certain transactions.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Legal Tender

Physical Euro: The physical Euro is established as legal tender across the Eurozone, mandated by law to be accepted for all cash transactions, reinforcing its use and trustworthiness (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: For the digital Euro to achieve the same status, it will need to be legally recognized as tender within the Eurozone. Ongoing legislative efforts aim to provide the necessary legal framework for its acceptance in all transactions (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020; IMF, 2020).

Both the physical and digital Euro rely on legal frameworks to establish their status as legal tender, ensuring universal acceptance and trust, making them comparable in this aspect.

Qualitative verdict: “0” Digital Euro and physical Euro perform equally well.

4.2. Reliability

- Medium of Exchange

Physical Euro: The physical Euro’s reliability stems from its wide acceptance and recognition within the Eurozone, backed by robust manufacturing standards that ensure its consistent quality and durability in daily transactions. The central bank’s rigorous control over its production guarantees a uniform and high-quality currency (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2024; ECB, 2024a; Europol, 2022).

Digital Euro: The reliability of the digital Euro depends largely on the underlying technology infrastructure, including its cybersecurity measures and the resilience of its digital network. Ensuring robust digital infrastructure is crucial to prevent outages and maintain consistent availability for transactions which only time can show (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020; IMF, 2020).

The physical Euro’s established reliability, supported by consistent quality and widespread acceptance, currently surpasses the digital Euro, which depends on the resilience of its developing technological infrastructure.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Unit of Account

Physical Euro: The physical Euro offers a stable and reliable unit of account due to the Eurosystem’s strong monetary policies and the currency’s wide acceptance for pricing goods and services across multiple countries. This stability is vital for maintaining economic coherence within the single market (Esselink & Hernández, 2017; Eurostat, 2024).

Digital Euro: For the digital Euro, reliability in this regard would also hinges on its integration into the existing financial systems and its acceptance by consumers and businesses alike. Ensuring its consistency as a unit of account would require rigorous regulatory standards and technological reliability (ECB, 2020; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2022).

The physical Euro’s established stability and widespread acceptance as a unit of account will surpass the digital Euro, which still depends on integration and acceptance within financial systems.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Store of Value

Physical Euro: While generally reliable, the physical Euro can suffer from physical degradation that may undermine its long-term value retention. However, the currency is designed to be durable, and central bank policies help protect its value against inflation (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2024; ECB, 2024a; Europol, 2022).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro’s reliability as a store of value will depend on digital security measures against hacking and fraud, as well as the stability of the digital currency system against market fluctuations and potential technological vulnerabilities (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020).

The physical Euro’s tangible nature and established mechanisms to protect against inflation provide greater trust in its reliability as a store of value compared to the digital Euro, which faces challenges related to technological security and system stability.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Standard of Deferred Payment

Physical Euro: The physical Euro is a dependable standard for deferred payments, supported by its legal tender status which mandates its acceptance. The security features integrated into its design also reinforce its reliability for future obligations (ECB, 2020, 2024b; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: Similarly, the reliability of the digital Euro for deferred payments would rest on its legal acceptance and the security of the digital contracts it supports. Legislative backing and technological integrity are key to its adoption and trustworthiness as a deferred payment medium (ECB, 2020; European Commission, 2023).

The physical Euro’s established legal tender status and integrated security features provide greater assurance as a standard for deferred payments compared to the digital Euro, which still requires full legal and technological integration.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Divisibility

Physical Euro: The physical Euro’s divisibility is well-established, with a comprehensive range of denominations that facilitate various types of transactions. The uniform standards applied across all denominations ensure their reliability in daily use (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2024; ECB, 2020; Europol, 2022).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro promises to extend this feature by potentially allowing even smaller denominations, or “micropayments,” enhancing its usability in the digital marketplace. The reliability of these transactions would be ensured through advanced digital ledger technologies (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020; IMF, 2020).

The digital Euro’s potential for micropayments and smaller denominations provides greater flexibility and usability, surpassing the physical Euro’s fixed divisibility limits.

Qualitative verdict: “+” Digital Euro performs better than physical Euro.

- Portability

Physical Euro: While reliably portable, the physical Euro’s utility in this regard is bounded by the physical volume and weight of the currency, particularly in large transactions (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2024; ECB, 2020; Esselink & Hernández, 2017; Europol, 2022).

Digital Euro: Digital currencies inherently offer superior portability without the physical constraints of traditional money. The digital Euro’s reliability in portability would largely depend on the accessibility and reliability of digital networks (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020; European Commission, 2023).

The digital Euro’s ability to eliminate physical constraints and facilitate secure, large-scale transactions regardless of location makes it significantly more portable than the physical Euro.

Qualitative verdict: “+” Digital Euro performs better than physical Euro.

- Durability

Physical Euro: The physical Euro is subject to wear and tear, which can affect its lifespan and reliability over time. Coins have a longer lifespan compared to paper notes, which are more vulnerable to physical damage (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2024; ECB, 2024a; Europol, 2022).

Digital Euro: In contrast, the digital Euro would not suffer from physical degradation, offering a theoretically infinite lifespan. The reliability of digital currency in this respect would be contingent on continuous digital maintenance and updates (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020).

The digital Euro’s immunity to physical degradation gives it a clear advantage in durability over the physical Euro, which is subject to wear and tear.

Qualitative verdict: “0” Digital Euro and physical Euro perform equally well.

- Fungibility

Physical Euro: The Euro is highly fungible, with each unit maintaining consistent value with others of the same denomination. This fungibility is crucial for its function as reliable currency and is strictly controlled by the issuing authorities (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2024; ECB, 2020; Esselink & Hernández, 2017).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro aims to ensure equal fungibility. The uniformity of digital units, verified via secure digital ledgers, would guarantee that each digital Euro is equivalent to another, maintaining this essential characteristic (ECB, 2020; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

Both the physical and digital Euro maintain strict fungibility, ensuring that every unit is interchangeable and holds consistent value, making them equally effective in this regard.

Qualitative verdict: “0” Digital Euro and physical Euro perform equally well.

- Recognizability

Physical Euro: The physical Euro is highly reliable in terms of recognizability due to its consistent and secure design features, including watermarks, holograms, and unique color schemes. These features help prevent counterfeiting and ensure that users can trust and easily identify genuine currency (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro’s recognizability will depend on robust digital authentication methods and user-friendly design. Ensuring that users can easily and confidently identify the digital Euro in transactions will be critical for its reliability. This will likely involve secure digital signatures and integration with existing financial apps (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020).

The physical Euro’s established design features and widespread familiarity ensure immediate and reliable recognizability, whereas the digital Euro will need time and technological integration to achieve comparable trust and ease of identification.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Scarcity

Physical Euro: The reliability of the physical Euro in terms of scarcity is managed through strict control by the European Central Bank, which regulates the supply of banknotes and coins. This controlled issuance helps maintain the currency’s value and prevents inflation (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; Eurostat, 2024).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro’s reliability in maintaining scarcity will be ensured by the European Central Bank’s ability to regulate its digital issuance. Advanced algorithms and regulatory oversight will help manage supply effectively, ensuring that the digital Euro retains its value and does not contribute to inflation (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020; IMF, 2020).

Both the physical and digital Euro benefit from the European Central Bank’s strict regulatory oversight, ensuring controlled issuance and maintaining scarcity to preserve value, making them equally reliable in this aspect.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Acceptability

Physical Euro: The physical Euro is highly reliable in terms of acceptability across the Eurozone, supported by legal mandates and widespread trust among consumers and businesses. Its tangible nature and established legal status ensure that it is universally accepted for transactions (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro aims to achieve high reliability in acceptability by integrating with existing payment systems and gaining regulatory approval. Its design will focus on ensuring seamless usability, security, and interoperability, which are critical for achieving widespread acceptance (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020).

The physical Euro’s universal legal mandate and tangible presence ensure immediate and widespread acceptability, whereas the digital Euro still requires integration and trust-building efforts to achieve comparable acceptance.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Legal Tender

Physical Euro: The physical Euro’s reliability as legal tender is firmly established, meaning it must be accepted for all cash transactions within the Eurozone. This legal backing ensures its universal trust and use, providing a stable and reliable medium for financial transactions (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: For the digital Euro to be reliable as legal tender, it will need to be legally recognized across the Eurozone. This involves establishing a comprehensive legal framework that supports its use for all types of transactions. Successful implementation will depend on regulatory approval and public trust (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020; IMF, 2020).

Both the physical and digital Euro rely on legal recognition to function as legal tender, ensuring universal acceptance and trust, making them equally reliable in this aspect.

Qualitative verdict: “0” Digital Euro and physical Euro perform equally well.

4.3. Perceived Quality

- Medium of Exchange

Physical Euro: The perceived quality of the physical Euro as a medium of exchange is influenced by the design integrity and security features of Euro banknotes and coins. High-quality printing, sophisticated anti-counterfeiting measures, and recognizable design elements enhance users’ trust in the authenticity and reliability of physical Euro currency (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2024; ECB, 2020; European Commission, 2023).

Digital Euro: For the digital Euro, perceived quality is tied to the security and reliability of digital payment systems. Robust encryption, multi-factor authentication, and reputable digital payment platforms enhance users’ confidence in the security and integrity of digital Euro transactions, contributing to its perceived quality as a medium of exchange (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020; IMF, 2020).

The physical Euro’s high-quality design and advanced security features foster trust in its authenticity as a medium of exchange, while the digital Euro’s perceived quality relies on the robustness of digital payment systems, which still need to achieve a comparable level of public confidence.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Unit of Account

Physical Euro: The perceived quality of the physical Euro as a unit of account is influenced by its design sophistication and recognition as a stable currency. Clear denomination markings, distinct design elements, and adherence to international standards contribute to users’ confidence in the Euro’s reliability and accuracy as a unit of measurement (ECB, 2020; Esselink & Hernández, 2017; Eurostat, 2024).

Digital Euro: Similarly, the perceived quality of the digital Euro as a unit of account depends on the reliability and trustworthiness of digital financial systems. Transparent pricing mechanisms, accurate accounting practices, and reputable digital platforms enhance users’ trust in the digital Euro’s integrity and accuracy as a unit of measurement (ECB, 2020; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

The physical Euro’s clear denomination markings, distinct design elements, and adherence to standards contribute to a higher perceived quality as a stable unit of account, whereas the digital Euro relies on the trustworthiness of digital systems, which still need to match the established reliability of the physical Euro.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Store of Value

Physical Euro: The perceived quality of the physical Euro as a store of value is influenced by users’ trust in its stability and security. Confidence in the Euro’s value retention, backed by central bank policies and economic stability, enhances its perceived quality as a reliable store of wealth (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2024; ECB, 2024a; Europol, 2022).

Digital Euro: For the digital Euro, perceived quality as a store of value is tied to the security and reliability of digital storage mechanisms. Trust in secure digital wallets, encryption protocols, and regulatory oversight enhances users’ confidence in the digital Euro’s reliability as a store of wealth (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020; European Commission, 2023).

The physical Euro’s perceived quality as a store of value benefits from established trust in its stability and central bank backing, while the digital Euro relies on secure digital storage and regulatory measures, which are still developing in terms of public trust.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Standard of Deferred Payment

Physical Euro: The perceived quality of the physical Euro as a standard of deferred payment is influenced by its widespread acceptance and recognition as a reliable form of currency. Trust in the Euro’s stability, enforceability of legal tender laws, and adherence to contractual obligations enhance its perceived quality for deferred payments (Esselink & Hernández, 2017; European Union, 1998, 2012; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: Similarly, the perceived quality of the digital Euro for deferred payments depends on users’ trust in digital contract systems and financial platforms. Confidence in the reliability of digital payment agreements, adherence to legal standards, and robust dispute resolution mechanisms enhance the digital Euro’s perceived quality as a standard for future obligations (ECB, 2020; European Commission, 2023).

The physical Euro’s established acceptance, legal backing, and stability enhance its perceived quality as a reliable standard of deferred payment, while the digital Euro still needs to build similar trust in digital contract systems and financial platforms.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Divisibility

Physical Euro: The perceived quality of the physical Euro’s divisibility is influenced by users’ confidence in its usability for transactions of varying sizes. Trust in the durability and functionality of Euro coins and banknotes, along with their widespread acceptance, enhances users’ perception of the Euro’s quality and reliability in divisible payments (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2024; Esselink & Hernández, 2017; Europol, 2022).

Digital Euro: In the digital realm, perceived quality as divisibility is tied to the efficiency and reliability of digital transaction systems. Confidence in seamless fractional transactions, accurate digital representations of currency, and secure digital platforms enhances users’ trust in the digital Euro’s quality and usability (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020; IMF, 2020).

The digital Euro’s perceived quality benefits from the efficiency and precision of digital systems for fractional transactions, while the physical Euro, though trusted for its divisibility, cannot match the seamless experience provided by digital platforms.

Qualitative verdict: “+” Digital Euro performs better than physical Euro.

- Portability

Physical Euro: The perceived quality of the physical Euro’s portability is influenced by users’ confidence in its ease of transportation and acceptance. Trust in the durability and recognizability of Euro banknotes and coins, along with the accessibility of cash distribution points, enhances users’ perception of the Euro’s quality and convenience for portable transactions (ECB, 2020; Esselink & Hernández, 2017; Eurostat, 2024).

Digital Euro: In the digital realm, perceived quality as portability depends on users’ trust in the accessibility and reliability of digital payment platforms. Confidence in seamless digital transactions, user-friendly interfaces, and secure digital wallets enhances users’ perception of the digital Euro’s quality and convenience for portable transactions (Bank of Canada et al., 2021; ECB, 2020; European Commission, 2023).

The digital Euro’s perceived quality in terms of portability benefits from the accessibility of digital payment platforms, allowing for seamless and convenient transactions, whereas the physical Euro, though portable, cannot match the ease and immediacy of digital portability.

Qualitative verdict: “+” Digital Euro performs better than physical Euro.

- Durability

Physical Euro: The perceived quality of the physical Euro’s durability is influenced by users’ trust in its resilience to wear and tear. Confidence in the longevity and authenticity of Euro banknotes and coins, supported by central bank policies and anti-counterfeiting measures, enhances users’ perception of the Euro’s quality and reliability over time (ECB, 2024a; Europol, 2022).

Digital Euro: In the digital realm, perceived quality as durability depends on users’ trust in the security and stability of digital payment systems. Confidence in protection against cyber threats, data integrity, and system reliability enhances users’ perception of the digital Euro’s quality and resilience over time (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020).

The physical Euro’s perceived durability benefits from its tangible resilience and anti-counterfeiting measures, fostering user trust, while the digital Euro’s durability relies on the perceived security and stability of digital systems, which still need to build similar long-term confidence.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Fungibility

Physical Euro: The perceived quality of the physical Euro’s fungibility is influenced by users’ trust in its interchangeability and uniformity. Confidence in the consistency and recognizability of Euro banknotes and coins, along with their widespread acceptance, enhances users’ perception of the Euro’s quality and seamless exchangeability in economic transactions (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2024; ECB, 2020; Esselink & Hernández, 2017).

Digital Euro: In the digital realm, perceived quality as fungibility depends on users’ trust in the consistency and reliability of digital payment systems. Confidence in the equivalence and interchangeability of digital Euro units enhances users’ perception of the digital Euro’s quality and usability in digital commerce (ECB, 2020; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

The physical Euro’s consistent design and recognizability foster confidence in its interchangeability, while the digital Euro relies on the reliability of digital payment systems to ensure equivalent fungibility, resulting in both performing equally well in terms of user perception.

Qualitative verdict: “0” Digital Euro and physical Euro perform equally well.

- Recognizability

Physical Euro: The perceived quality of the physical Euro is high due to its well-established and distinctive design features, such as unique color schemes, architectural images, and advanced security elements like holograms and watermarks. These features not only make the currency easily recognizable but also convey a sense of trustworthiness and authenticity, which is essential for maintaining public confidence (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: The perceived quality of the digital Euro in terms of recognizability will depend on its digital interface esthetics and security features. It must incorporate familiar visual cues from the physical Euro, such as color schemes and symbolic graphics, to ensure users can easily recognize it. Additionally, robust digital security features will be crucial to maintain trust and ensure the currency is easily distinguishable from other digital assets (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020).

The physical Euro’s distinctive design features, including unique color schemes and advanced security elements, enhance its recognizability and trustworthiness, while the digital Euro still needs to establish similar visual cues and security measures to achieve equivalent recognizability.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Scarcity

Physical Euro: The perceived quality of the physical Euro in terms of scarcity is reinforced by the European Central Bank’s strict control over its issuance. The advanced security features and intricate designs signal that the currency is well-regulated and not easily counterfeited, thus preserving its scarcity and value. This control over supply helps maintain the currency’s perceived quality and economic stability (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; Eurostat, 2024).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro’s perceived quality in maintaining scarcity will rely on the European Central Bank’s ability to manage its digital issuance effectively. Using advanced digital infrastructure, the bank can ensure that the supply of the digital currency is controlled and transparent, thereby preserving its scarcity and perceived value. The public’s trust in the digital Euro will depend significantly on the perceived rigor of its issuance and regulation (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020; IMF, 2020).

The physical Euro’s scarcity is perceived as high due to strict issuance controls and advanced security features, which enhance trust in its value, whereas the digital Euro still needs to establish public confidence in its controlled and transparent digital issuance.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

- Acceptability

Physical Euro: The physical Euro enjoys high perceived quality in terms of acceptability due to its established legal status and widespread use across the Eurozone. Its tangible nature, combined with sophisticated security features and consistent design, ensures public trust and universal acceptance for transactions. The physical Euro’s esthetic appeal and reliability further enhance its perceived quality (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: The digital Euro must achieve high perceived quality in acceptability by offering a seamless, secure, and user-friendly experience. Its design should be visually appealing and consistent with the physical Euro to facilitate trust and ease of use. Legal frameworks supporting the digital Euro’s use will be crucial for its acceptability, along with ensuring that it integrates well with existing digital payment systems (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020).

While the physical Euro’s established legal status and tangible nature support its high acceptability, the digital Euro’s perceived quality in acceptability benefits from its potential for seamless and secure integration into digital payment systems, offering greater convenience in modern transactions.

Qualitative verdict: “+” Digital Euro performs better than physical Euro.

- Legal Tender

Physical Euro: The perceived quality of the physical Euro as legal tender is solidified by its official status and the legal frameworks mandating its acceptance for all transactions within the Eurozone. The clear and consistent design elements, including national emblems and security features, visually reinforce its legitimacy and legal standing, which is essential for public trust and widespread use (ECB, 2024a; European Commission, 2023; IMF, 2020).

Digital Euro: For the digital Euro to achieve high perceived quality as legal tender, it must be supported by comprehensive legal recognition and robust regulatory frameworks. Ensuring that the digital Euro is legally accepted for all types of transactions will be crucial for its perceived quality. Consistent and secure digital design elements, reflecting its official status, will help convey its legal authority and ensure user trust (Bank of Canada et al., 2020; ECB, 2020; IMF, 2020).

The physical Euro’s established legal status and recognizable design elements strengthen its perceived quality as legal tender, while the digital Euro still requires comprehensive legal recognition and secure design to match the same level of public trust and acceptance.

Qualitative verdict: “−” Physical Euro performs better than Digital Euro.

The results of this qualitative comparison are displayed in summary form in Table 2.

Table 2.

Qualitative comparison of Digital Euro and Physical Euro.

In the next step this comparison is detailed by comparing the physical Euro to the Digital Euro in an ordinal fashion. For this purpose, a plus sign (+) is assigned if the Digital Euro is judged to perform better than the physical Euro, a minus (−) if the physical Euro outperforms the Digital Euro, or a zero (0) if they are considered functionally equivalent in that regard. When comparing the physical Euro to the Digital Euro in an ordinal way, advantages and disadvantages become apparent as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Ordinal comparison of Digital Euro and Physical Euro.

Across 8 instances of pairwise comparisons, the Digital Euro outperforms the physical Euro when it comes to quality and the characteristics of money. In 20 cases the physical Euro performs better than the Digital Euro. In the remaining 8 comparisons, they perform equally well.

Given the substantial differences across many characteristics and dimensions of quality, the null hypothesis derived from the underpinning research question has to be rejected:

H0:

The Digital Euro is an electronic equivalent of physical Euro cash in terms of the characteristics of money and the dimensions of quality.

Instead, the alternative hypothesis finds support:

H1:

The Digital Euro is not an electronic equivalent of physical Euro cash in terms of the characteristics of money and the dimensions of quality.

The assertion that the Digital Euro could function as a complete electronic equivalent of the physical Euro cash cannot be upheld.

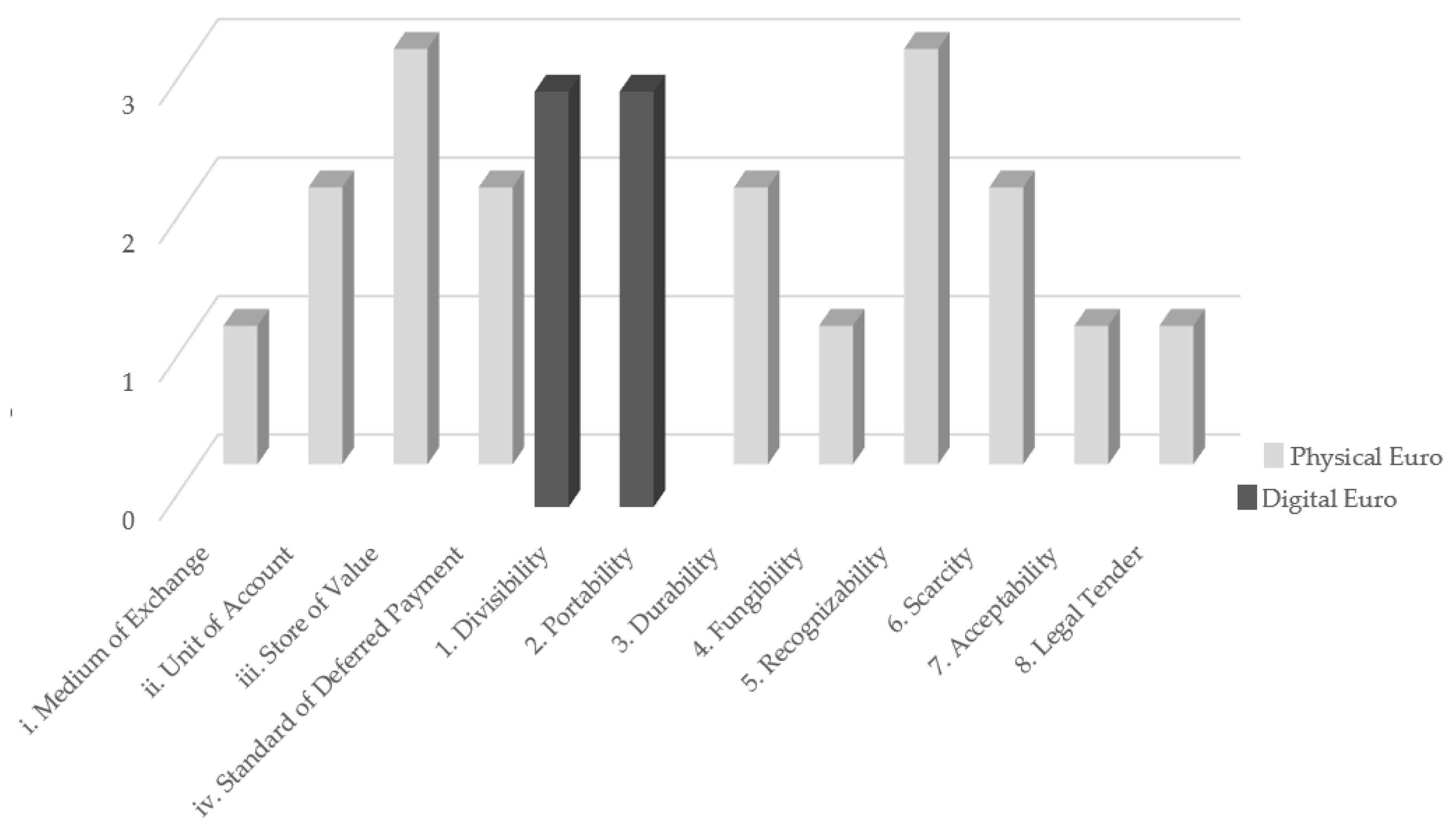

When building the sums of pluses and minuses presented in the table above and displaying the absolute value for the Digital Euro in case the sum is positive and for the physical Euro in case it is negative, the graph depicted in Figure 1 emerges.

Figure 1.

This figure displays in a comparative fashion the scores of the Digital Euro vs. the physical Euro along the twelve attributes of money.

The comparative assessment of the Digital Euro and physical Euro along twelve attributes of money reveals a distinct allocation of strengths between the two forms of currency. The attributes are evaluated on a scale from 0 to 3 due to the three quality dimensions of money (Performance, Reliability, and Perceived Quality), to determine the relative performance of each Euro form across monetary functions.

In terms of the core functions of money, the physical Euro exhibits higher scores in medium of exchange (1 vs. 0), Unit of Account (2 vs. 0), Store of Value (3 vs. 0), and Standard of Deferred Payment (2 vs. 0), demonstrating its continued dominance in traditional roles.

The Digital Euro outperforms the physical Euro by a great margin in both Divisibility and Portability (3 vs. 0 for both). However, in Durability, the Physical Euro scores higher (2 vs. 0). The physical Euro also has a slight lead in terms of Fungibility (1 vs. 0), but significantly higher one on Recognizability (3 vs. 0). Also, in terms of Scarcity, the physical Euro scores higher than its digital counterpart (2 vs. 0) and so it does for Acceptability and Legal Tender, but by lesser margin (1 vs. 0).

5. Discussion

The analysis presented in the previous section reveals that, overall, the physical Euro outperforms the Digital Euro across several critical dimensions of money and quality. This section will discuss these findings extensively, highlighting not only the areas where the physical Euro excels but also critically examining the limitations and challenges associated with the Digital Euro. The discussion is supported by relevant literature, offering a comprehensive perspective on the comparative performance of these two forms of currency.

The physical Euro remains a highly effective medium of exchange due to its established acceptance and immediate usability. Its physical tangibility ensures that transactions can be completed instantly without the need for digital infrastructure, making it indispensable for daily transactions, particularly in scenarios where digital access is limited or unreliable (Esselink & Hernández, 2017). While the Digital Euro promises enhanced transaction speed and geographical reach, its—at least occasionally—reliance on Internet access presents a significant limitation. The need for a robust digital infrastructure means that the Digital Euro cannot yet match the universality and reliability of the physical Euro in all contexts (Bank of Canada et al., 2020).