1. Introduction

The principal constraint to developing existing companies or creating new businesses is related to the restrictive conditions that financial institutions require on credit allocation. The concept of private equity came to fill this problem. It has been proven to accelerate company growth by introducing new products (or services) in the market. US experts affirm that companies that receive private equity capital increase their market share at a higher rate of 1.88% compared to those without private equity funds, which increases company revenues and sales and, consequently, company growth (

Alsina, 2013). Private equity is considered as a key to innovation. It contributes to job creation, promotes company investments, increases companies’ internalization capabilities, and lowers companies’ failure rate. Private equity has adopted socially responsible investment policies as an important element when deciding to invest.

As noted by highly regarded private equity associations (ASCRI, EVCA, and BVCA) and the

World Economic Forum (

2022), private equity has been proven to be a powerful tool for economic growth and an efficient source of financing for SMEs. Therefore, the cooperation between private equity and SMEs is rewarding for the economy, investors, and private businesses. The private equity sector has proven to be a driver of economic growth and is increasingly interested in the region. If we combine these two elements, we obtain a great opportunity for economic growth in the region, which needs government support to crystallize.

In the literature, several authors, such as

Harris et al. (

2018,

2023),

Lerner et al. (

2023),

Unruh and Rice (

2025), and

Sorensen and Yasuda (

2023), consider private equity an “appropriate” form of financial intermediation to support the financing of business creation and growth. However, private equity is a riskier business; hence, investors conduct a thorough assessment before investing in a company’s capital. In fact, project selection will bear on a certain number of criteria in line with a well-defined process. They also invest in other sectors or projects that promise a higher return that would cover the risk they take (

Boulton et al., 2007;

Citron & Wright, 2008;

Cressy et al., 2007;

Davis et al., 2008).

Many theories have been used to conceptualize research studies on private equity investment criteria. For example, the institutional theory focuses on norms, rules, and structures within countries. This theory is based on the principle that individuals are expected to accept and follow social norms (

Tolbert & Zucker, 1999). According to

Scott (

2005), this theory can be considered as a process by which rules have become authoritative guidelines for social behavior.

Kollmann and Kuckertz (

2010) presented their study by reference to the theory of information economics, according to which investment criteria are considered as “enabling the identification of valuation uncertainties”. Others, like

Feeney et al. (

1999), have selected the agency theory to present their study of private investor criteria, which focuses on the problems and conflicts between principal and agent. The resource-dependent theory has also been selected as it considers firms as open systems that should transact with other organizations (including private investors) to obtain resources such as equity funding. We also cite the strategic alliance theory, which refers to the cooperation between two parties to pursue mutual strategic objectives. According to the control theory, private equity-backed firms exercise more active monitoring and stricter control. According to this theory, the more concentrated ownership structure of private equity-backed firms leads to stronger shareholder control and more frequent CEO replacement in the event of poor performance than the dispersed ownership structure of listed firms.

Finally, the theory of the “internal information” hypothesis put forward by

Cornelli and Karakas (

2015) suggests that sophisticated investors (especially specialized private equity firms) are more inclined to use “soft” (internal) information to assess the competence of the CEO and to decide on their investment.

In this work, we are not seeking to compare the investment criteria of Tunisian private equity investment professionals with those of other countries but to think about existing criteria practices in making investment decisions. That is why the institutional theory seems to be the most relevant theory to our study.

From a theoretical perspective, our study contributes to the literature on private equity by deepening our understanding of how different types of private equity investors make investment decisions to minimize the risk linked to private equity investment. In fact, despite the importance of investment selection, only a few studies have yet assessed how private equity investors actually select their investments and conduct investment decisions. In this work, we try to shed light, for the first time, on the investment criteria used by Tunisian private equity investors when making investment decisions. The collective view of professionals was helpful in prioritizing the most important decision-making criteria.

In this context, many studies tried to identify the investment criteria used by private equity investors (

Hamman et al., 2021;

Dhochak & Sharma, 2016;

Muhammad et al., 2017;

Block et al., 2019;

Gompers et al., 2016;

Kollmann & Kuckertz, 2010). However, according to

Eloranta (

2018), the literature lacks consensus regarding the relevance of essential aspects, which poses challenges when considering private equity investment.

Private equity is relatively new in North African countries. Although some started operating in the industry by the 1980s, Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia started operating by 2000. In these twenty years, the development of this industry has been uneven: from 2003 to 2007, private equity funds grew in the region alongside the worldwide growth trend; from 2008 to 2009, the industry suffered from a period of recession; and since 2010, we have been witnessing a promising upturn of this sector.

The trend in the North African region has ordinarily been to invest in development investment projects of a considerable size; energy, infrastructure, and real estate are the main sectors for investment. Now, the trend might be changing. Funds invested in start-ups and venture stages of IT or cleantech firms have been increased, which has been encouraged by the government. The latter has implemented initiatives such as Business Angels, which are oriented towards promoting investments in business projects and start-ups (

Alsina, 2013).

To finance its economy, Tunisia was the first Arab country to open up to the private equity sector. Tunisia began operating in this market in 1990, and although its legislation and regulatory framework are quite advanced, private equity funds are still not fueling the Tunisian economy. In Tunisia, the legal framework established by laws 95-87 and 2008-78 provides for three vehicles to channel private equity investments, namely Venture Capital Investment Company, Seed Capital, and Venture Mutual Capital Funds (VMCF). The law applies the same requirements to these three vehicles in terms of investment and tax incentives. Here again, Tunisia, like Morocco, has a restrictive legal framework allowing investors to promote private equity. In the case of Tunisia, the restrictions concern the target companies. The law requires that these investments be targeted at “businesses located in development zones” or at “improved businesses”. These two requirements clearly illustrate how restrictive legal frameworks can prevent the private equity industry from growing. According to experts, cultural aspects of business management can also explain Tunisia’s underdevelopment of private equity. In Tunisia, there is a culture of debt, and the Tunisian population is still inclined to keep SMEs in the hands of the family. In summary, although Tunisia has more developed legislation, the requirements linked to zoning or SMEs prevent private equity from growing in this country.

Analysis of the current situation of private equity funds in the North African region, and among others in Tunisia, shows that private equity funds in the North African region are scarce. In fact, the existing funds have a very low, almost insignificant, impact on the economy of the region. Therefore, the region is missing the great economic and social impact that the private equity industry could provide. Furthermore, there is a lack of commercial investors in the region. Commercial investors are essential to this profession. They learned to identify investment opportunities and invest in private equity funds; therefore, they drive investments via the channels of private equity companies. This low number of commercial investors in the region is due to several aspects. First, local capital flow investing across the region is non-performing due to the control that the Central Banks exercise on money flows. Second, there is a lack of professionals in the region, which makes size attractive to general partners as the country funds are too small for financing good quality teams. Finally, regulatory frameworks are too restrictive, which prevents the development of the private equity industry itself locally, enabling the promotion of cash flow interaction regionally.

The record of private equity in Tunisia is mixed. Indeed, although Tunisia has the merit of being the first Arab country to have introduced private equity in 1988 as an alternative to financing its economy, and a reform was already initiated in 2011, private equity, unfortunately, failed its start-up, has always represented a last resort for business leaders and remains insufficiently efficient and with a low employability rate. Moreover, because private equity is a riskier business, investors thoroughly assess before investing in a company’s capital. Project selection will bear on a certain number of criteria in line with a well-defined process.

Furthermore, this work allows us to make many other contributions. First, we identify the relative importance of private equity investors’ investment criteria. Overall, the most important investment criteria in project selection are the following: (1) characteristics of the target product market, (2) contribution of managers in terms of competence, (3) financial contribution of the managers, and (4) anticipated exist horizon revenue growth. Forecasts of the dividend yield rate and general stock market conditions are relevant but of lower importance. In this regard, we can say that although the sample selected for this research is of moderate international relevance, it is made up of qualified practitioners, including CFOs and Managing Directors with significant private equity experience. It also provides a solid basis for a rigorous analysis of private equity investment criteria. Our results corroborate those of studies carried out in other contexts, notably the French context and the British context, which allows the generalization of these results. This study makes a major contribution to the still scant literature on private equity in emerging economies. It also enables interesting comparisons with other contexts, reinforcing its theoretical and comparative value from an international perspective.

Second, most studies and research analyzing the private equity sector in the Middle East. The North African region tends to focus more on the Middle East and less on North Africa. The case of Tunisia is probably the most attractive in the North African region regarding the transformation phase that the industry is going through there. Therefore, the principal object of this study is to provide some important elements to describe the private equity dynamic in Tunisia.

Third, stakeholders can benefit from a better understanding of the most important aspects that affect the decisions of Tunisian private equity investors. In fact, this study provides practical information for investors in Tunisia. Specifically, it helps investment companies to present the process of handling an investment file and to examine the project selection criteria used by Tunisian equity investors.

Fourth, this work can also benefit firms that want to attract funding from private equity investors. The results will aid in organizing themselves to become attractive investment opportunities. Furthermore, Tunisian professionals in private equity can use the results of the study to benchmark and assess their current investment decision-making practices.

Finally, results reveal that in the context of informational asymmetry between investors and entrepreneurs, these investment companies give greater weight to business plans drawn up by management. In such a context, this study encourages investors to use certified audit reports, showing the importance of accounting information in this process. Indeed, this study makes several significant contributions to the field of accounting, particularly in terms of assessing the quality of accounting information and its impact on investment decisions. The study shows that the quality of accounting information, namely certified, is a determining factor in private equity investment decisions. Thus, high-quality accounting information reduces information asymmetry between investors and firms, facilitating a more accurate assessment of risks and opportunities. This is particularly relevant in emerging markets, where financial information can be less transparent and reliable. In addition, by highlighting the importance of quality accounting information, the study contributes to the debate on corporate governance in Tunisia. Reliable and transparent accounting information is essential for efficient and responsible management, which can boost investor confidence and improve access to private equity financing. The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows: The next section is a literature review that is necessary to find the criteria to be assessed in the questionnaire.

Section 2 presents the research design, including the sample and hypothesis formulation, and discusses the study results. The last section concludes the paper.

2. Theoretical Background, Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Until now, the lack of credit problems, the established restrictive conditions, and the conditions required by financial institutions on credit allocation remain the main constraints to the development of existing companies or the creation of new businesses. It is in this context that the concept of private equity came to fill this problem.

Considered an alternative means of financing investments, it first appeared in the United States in 1946, after the Second World War. The first venture capital vehicle was founded by MIT President Karl Compton and Harvard professor Georges Doriot with input from others in the Massachusetts community, where they chose to invest in high-risk companies developing technology during World War II. This venture capital entity and the funds that followed were structured as exchange-traded funds.

In 1958, the first venture capital company, legally termed “Limited Partnership, LP”, was created. However, during the 1960s and 1970s, exchange-traded funds and small business investment companies were the most common.

At the beginning of the 1980s, and thanks to changes in the regulations of institutional investors, the Limited Partnership (LP) format became the most common legal form thanks to its tax advantages. In 1978, the US Department of Labor removed barriers to entry, preventing US institutional funds from devoting some of their assets to venture capital. Hence, there was an increase in the amounts dedicated to venture capital thanks to the contribution of American organizations.

In 2000, private equity experienced strong growth thanks to the combination of many favorable factors, such as the revolution in information technology, controlled inflation, and favorable regulatory conditions. Subsequently, it has been the subject of many books and research studies in which the authors have studied and analyzed all its different aspects.

Replacing debt and initial public offerings (IPOs), private equity, as presented in most documents, is an investment in equity or quasi-equity for a fixed period, generally not exceeding 7 years, in off-stock market entities. Indeed, investment capital companies take several forms depending on the legislation of the countries.

According to

Bayliss et al. (

2023), the shift from “managerial capitalism” to “financial capitalism” has resulted in a shift in economic agents, illustrated by the growing importance of private equity financing. This latter has been growing at a rate of over 10% per year since 2004.

Even though they mean the same, there are different ways of defining private equity. The French Association of Capital Investors (FACI) previously, France Invest Now, defines private equity as “real equity financing, i.e., exposed to business risks, without guarantees or entrepreneur or company; which takes the form of equity participation, most often a minority; for a limited period and supposed to cover the period necessary for the success of the project (from 3 to 7 years most often)”.

Moreover, the European Private Equity and Venture Capital Association, known as EVCA, suggests that “private equity is the contribution of equity capital by medium or long-term financial investors to unlisted companies with strong growth potential”.

In the literature, several authors, such as

Harris et al. (

2018,

2023) and

Lerner et al. (

2023), consider private equity as an “appropriate” form of financial intermediation to support the financing of business creation and growth.

Private equity is considered as closed capital, which cannot be exchanged freely, i.e., violators will be imprisoned for a period of time. This American terminology highlights both the non-negotiable and unlisted dimensions of the concept. It generally consists of a set of two activities, which are “venture capital, VE” and the acquisition of mature entities, “leveraged buyouts, LBOs”.

Sannajust and Groh (

2020) concluded that entrepreneurial private equity is needed, characterized by the demanding stance of the active minority shareholder and inspired by what American venture capital has been promoting for nearly 60 years. This conclusion is counterintuitive for those who focus on the visible characteristics of the SMEs considered: mature SMEs in emerging countries operate in traditional activities, are profitable, and exhibit moderate growth; in contrast, start-ups in developed countries operate in technological sectors, are structurally loss-making, and exhibit strong growth.

The conclusion of their research thus leads them to scientifically qualify the hypothesis of an entrepreneurial private equity model for emerging countries. Far removed from the figure of the financier who reads the past, designs the present, and projects the future through the analysis of reports and the simulation of mathematical models, the entrepreneurial capital investment that they offer for emerging countries presents itself as the double of the business leader, his alter ego in the financial sphere.

Kaplan and Strömberg (

2009) explain private equity through a study of LBOs and the private equity sector. The authors explain that a Corporate Investment (CI) company raises capital through a fund called a private equity fund. Most of these funds are considered “closed-end funds”, i.e., entities with fixed capital, in which investors have committed to pay an amount of money to finance corporate investments and pay management fees to CI companies.

These funds are structured as “Limited Partnerships” in which the “General Partners, GPs” manage the fund and the “limited partners, LPs” provide most of the capital.

Limited partners are generally institutional investors, such as public and private pension funds, banks, insurance companies, public authorities, “Sovereign wealth” (investing in innovation), and “family offices”. They can also be natural persons: “business angels” and wealthy people.

Equity investors are active investors who focus on the main challenges of the business without interfering in management. They are generally former entrepreneurs or former managers who invest in sectors in their field of expertise to capitalize on their experience and create a motivating environment for the management teams of the companies in which they invest. This is a real transfer of know-how to improve their potential for value creation. On the other hand, they also invest in other sectors or projects that promise a higher return that would cover the risk they take (

Boulton et al., 2007;

Citron & Wright, 2008;

Cressy et al., 2007;

Davis et al., 2008).

In addition to the traditional analysis of financial performance, in order to minimize the risk of their investment, they collect extra-accounting and qualitative information, such as the degree of expertise of entrepreneurs and the product’s features and market potential to circumvent information asymmetry governing the relationship between the capital investor and the company.

When studying a project, private equity investors are faced with a problem of contrary selection with regard to the project itself and a moral risk concerning the manager of the firm (

Sahlman, 1990;

Amit et al., 1993).

Private equity investors can limit risk of their investment, a priori, notably by carrying out an in-depth study of the project. The modes of regulation, a posteriori, are essentially based on rigorous control of the evolution of the performance of the firm and the behavior of entrepreneurs. Our study is located in the ex-ante management of the risk of opposite selection. We are interested in the criteria used by private equity investors to select their investment projects.

Muhammad et al. (

2017) used a pooled method and included individual criteria, company and industry criteria, and institutional or environmental criteria, which cover environmental risks and country conditions.

Block et al. (

2019) applied seven criteria: product/service and international scalability, profitability, reputation of the current investor, track record of the management team business model, and revenue growth.

Eloranta (

2018) noted that most studies followed the study of

Tyebjee and Bruno (

1984), based on a four sub-criteria framework of sub-criteria, which are the entrepreneur/management, product, market, and financial teams’ features. In the same line of research, some have structured their investment criteria into a certain number of subsections. From the literature, we grouped the investment criteria into the following four sections: investment phases, intervention framework (or sector criteria), investment and target-specific considerations—including manager competence, target product market, exit horizon, and dividend yield rate—and general stock market conditions (

Block et al., 2019;

Eloranta, 2018;

Muhammad et al., 2017;

Tyebjee & Bruno, 1984).

Works carried out on the selection criteria for capital investment projects, which initially involved essentially descriptive approaches to the variables taken into account, have gradually assessed their relative importance. For example,

MacMillan et al. (

1985) show that one of the most important sources of information is the business plan, which includes the entrepreneurs’ projections about the firm and presents the technical, legal, economic, and financial structuring of the project.

MacMillan et al. (

1988) also show that the degree of expertise and experience of the entrepreneur are particularly important selection criteria, dominating those relating to the company’s markets and products.

Fried et al. (

1993) find that capital investors are more interested in market absorptive capacity than in high potential rates of return and rapid exit.

The study by

Muzyka et al. (

1996) points out that ICs make trade-offs between different criteria in their investment selection process, a practice not taken into account in previous studies. On the basis of joint analysis, the authors find that of all the criteria required, a priori, private equity investors give the most importance to the management team and financial and product/market characteristics of the project under consideration. These results are corroborated by

Wright and Robbie (

1996), who show that private equity investors investing in British companies carry out a detailed and meticulous examination of all aspects of the business, paying particular attention to management CVs, discussions with contractors and staff, and give considerable weight to unpublished information (e.g., sales, marketing, production capacity, etc.) and subjective information (e.g., degree of involvement and entrepreneur potential).

These various studies show that private equity investors basically select their investments on the basis of the business plan, followed by other information on the characteristics of the company’s management, products, and markets. This rationality will be verified in our case if the following hypothesis is validated:

H1. In their selection process for investment projects, the Tunisian private equity investors give the greatest importance to the business plan, followed by the characteristics of the company to be financed.

In addition, various factors such as budgetary and time constraints, as well as other situational factors, can have a direct influence on the due diligence process during the project selection phase (

Harvey & Lush, 1995). It can be difficult to obtain sufficient, relevant, and high-quality information within a satisfactory particularly when the target company is small. Entrepreneurs may also intentionally or unintentionally withhold important information or communicate a distorted version of key facts (

Sahlman, 1990;

Amit et al., 1993). The increased cost of due diligence, relative to the amount invested and the time, can be detrimental to the completion of the transaction (

Wright & Robbie, 1996). However,

Wright and Robbie (

1996) have also shown that accounting data are the most important element in the due diligence report of British private equity investors. It is, therefore, expected that private equity investors place greater importance on certified reports issued by independent auditors than on uncertified accounting information, particularly that provided by the management team.t team. This preference should be all the more pronounced if the project is highly innovative or is being carried out in a market where historical data are scarce and forecasts are difficult. This leads to the following proposal:

H2. When selecting their investment projects, private equity investors place greater emphasis on certified reports issued by independent auditors or accountants than uncertified accounting documents.

2.1. The Experience of Tunisian Private Equity

In the Arab world, Tunisia is considered the first country to have introduced private equity into its financial system and to have established the concept of investment companies in Tunisian legislation in 1988 by law N° 88-92 of 2 August 1988.

Since then, the private equity sector in Tunisia has been faced with several restrictive factors. The law has often been modified over the last decades in order to remedy shortcomings and relaunch venture capital. Indeed, the law underwent several amendments in 1992, 1995, 2001, 2008, and 2011. Such amendments help us track the progress of the regulatory framework of private equity.

During the sixties and after independence, the first entrepreneurs of Tunisia were forced to deal with banks, the only creditors in the country, to finance their projects. However, the latter was very demanding and refused to finance most projects considered “innovative” or “out of the ordinary” by classifying them as projects with a high-risk potential. In fact, banks only finance projects operating in the real estate sector, the business sector, or the food sector.

This precautionary behavior of banks created a restricted and minimal economic and financial environment. Pressure from “innovative” entrepreneurs, who do not have enough equity required by banks or do not have guarantees to obtain a loan, has led the Tunisian State to create a set of funds such as the fund for industrial promotion and decentralization, the FOPRODI

1, to relaunch and diversify the country’s development. This attempt also aimed to encourage SMEs and strengthen the business climate. Thus, thanks to the encouragement of the State, manifested in the law of April 1972, a new range of industries intended for external markets was created.

The 1970s were also marked by the appearance of development banks. These institutions are more open and flexible in terms of diversity and cost of investment since they play the role of creditor and partner at the same time because they participate in the project’s capital.

Unlike commercial banks, development banks invest in agri-food projects, the chemical and pharmaceutical industry, tourism, and even hotels.

Around the 1980s, the Tunisian economy was booming, which led to an increase in demand for equity by entrepreneurs. Accordingly, the Tunisian legislator enacted the first law on investment companies, law N° 88-92 of 2 August 1988.

This law defines the objective of venture capital investment companies (VCICs) as “participation, for their own account or for the account of third parties and with a view to its retrocession or assignment, in the strengthening of opportunities for investment and equity of companies established in Tunisia and unlisted with the exception of those operating in the real estate sector relating to housing”.

From this definition, we see that venture capital is a series of all investment operations in equity or quasi-equity in companies most often not listed on the stock exchange to finance all stages of a business life cycle.

However, the European Private Equity and Venture Capital Association (EVCA) defines venture capital as “a part of private equity investments made for the launch, initial development and ‘expanding a business’.

According to these two definitions and those presented above, we notice that the definition of Law No. 88-92 of 2 August 1988 confuses investment capital with venture capital. The Tunisian legislator has, in fact, given the same meaning to the two concepts, which has generated a vague vision of the nature of private equity in general and, therefore, its scope of intervention.

Thus, this law gave rise to two different categories of investment companies, in particular, Variable Capital Investment Companies and Fixed Capital Investment Companies.

These two entities were created with the aim of participating financially in the capital of companies claiming funds. Since then, the law in question has been amended in 1992 and 1995.

Indeed, laws N° 92-113 of 23 November 1992 and N° 95-87 of 30 October 1995 come to modify and supplement that of 2 August 1988. In addition, the last law introduced a new class of investment companies: Venture Capital Investment Companies (VCICs).

The law of 30 October 1995 indicates that VCICs are required to participate on their behalf or on behalf of third parties in the capital of:

- −

Companies located in regional development zones (RDZs) (articles 23 and 34 of the investment incentive code),

- −

Projects for SMEs (article 44 of the investment incentive code),

- −

Companies promoting technology or its mastery, as well as those investing in innovation,

- −

Companies that can benefit from the deduction of income or profits reinvested in transmission operations,

- −

Investments made by member companies of the upgrading program and approved by the steering committee of this program,

- −

Companies in economic difficulty that can benefit from the deduction of income or profits reinvested in transmission operations.

According to the Budget Law of 2001, law 2000-98 of 25 December 2000 encourages Venture Capital Investment Companies to invest at least 30% of their resources in new technology projects. In fact, any investment made in this sector will benefit from the same tax advantages granted to projects carried out in the regional development zones.

According to Article 21 of Law No. 2008-78 of 22 December 2008, amending legislation on venture capital investment companies, Venture Capital Investment Companies are required to invest at least 65% of their paid-up capital and at least 65% of each amount made available to them in the form of venture capital funds unless they come from foreign financing sources or from the State budget.

Apart from the organizations mentioned above, the Tunisian legislature has introduced investment funds called mutual funds of risky investments.

Thus, under the terms of Article 21 of Law No. 88-92 of 2 August 1988, as amended and supplemented by subsequent texts, venture capital funds are required to invest at least 65% of their assets in a period not exceeding the end of the year following issuance of shares.

The tax and financial benefits for investments in regional development zones that previous laws have guaranteed only guide the choice of private equity investment towards these zones. Due to pressure from private equity investors to promote the sector in Tunisia, the legislature enacted a new reform in 2011.

Decree-Law No. 2011-99 of 21 October 2011 was drawn up in order to broaden the scope of intervention of industry players and introduce more incentives in the field.

Indeed, the field of intervention of Venture Capital Investment Companies and Venture Mutual Capital Funds (VMCF) has become a “free” field where they have the choice of intervening in all Tunisian companies not listed on the stock exchange with the exception, of course, of those operating in the housing-related real estate sector. Thus, instead of investing 65% at least, the minimum threshold has become 80% of their denominated capital within a period not exceeding the end of two years following the year in which the subscribed capital or the shares subscribed have been issued or the amounts made available have been released.

The new contribution of this decree-law is the appearance of the “fund of funds” concept. To this end, article 22 has been added to the Code of Undertakings of Collective Investment in order to explain that Venture Mutual Capital Funds have the possibility of being set up as funds using their assets to subscribe to units of Venture Mutual Capital Funds provided for by the Code. Seed fund units were also provided for by Law No. 2005-58 of 18 July 2005.

In addition, Venture Mutual Capital Funds can hold the majority of shares in the capital of the companies in which they invest. Decree-Law No. 2011-100 of 21 October 2011 aims to adapt the tax framework to the field of intervention of private equity players, which was amended by the previous decree-law. It also established a special regime for organizations specifically dedicated to regional development.

To conclude, here is the list of laws currently applicable to private equity operations:

- −

Law 88-92 of 2 August 1988 relating to investment companies, amended by Law No. 2008-78 of 22 December 2008, the two decree-laws No. 2011-99 and No. 2011-100 of 21 October 2011;

- −

The Code of Undertakings for Collective Investment enacted by Law No. 2001-83 of 24 July 2001 and rectified by Decree-Law No. 2011-100 of 21 October 2011;

- −

Law No. 2005-58 of 18 July 2005, associated with seed funds.

2.2. The Tunisian Private Equity Sector During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The virus has not reaped the lives of a number of victims only, but it has also affected the global economy. At the national level, the year 2020 was marked by Tunisia’s most severe economic decline since its independence.

The following

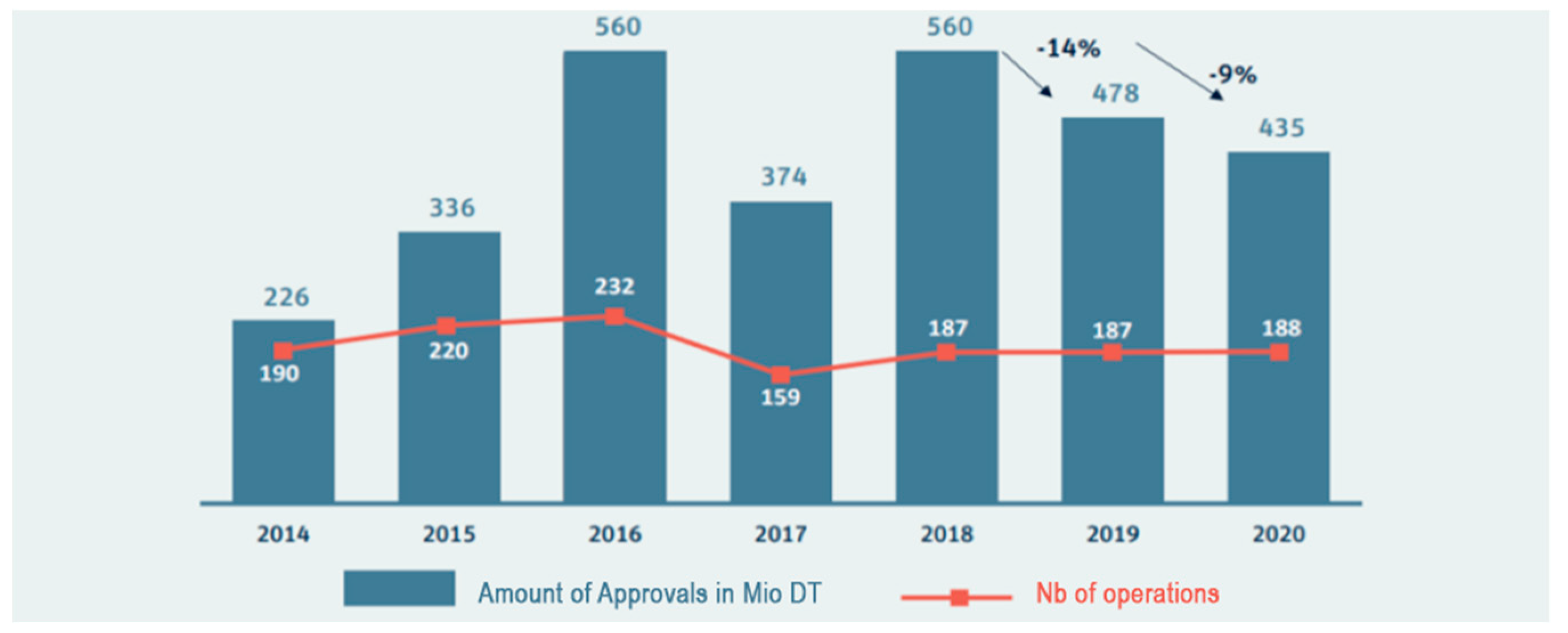

Figure 1 shows the evolution of investments and approvals between 2014 and 2020.

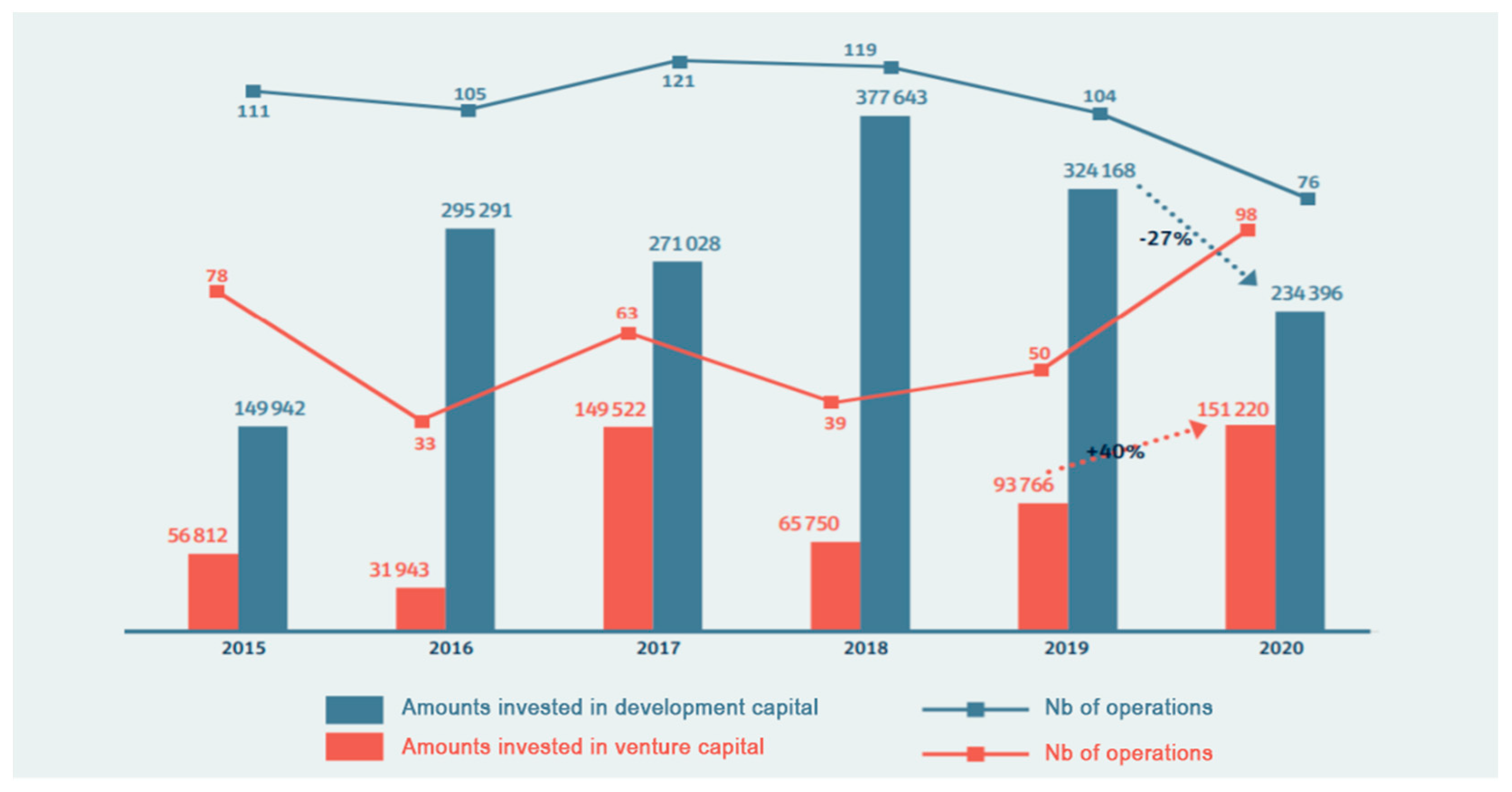

The crisis has increased venture capital investments and reduced those in development capital. The amounts invested in the former are around 151 MD (i.e., 40% in 2020 compared to 2019). Thus, the number of companies financed increased from 50 to 98 between 2019 and 2020, an increase of 96%. As for the decline in development capital investments, there was a drop of 27% in the amounts invested.

The following

Figure 2 shows the Evolution of venture capital and development capital between 2015 and 2020.

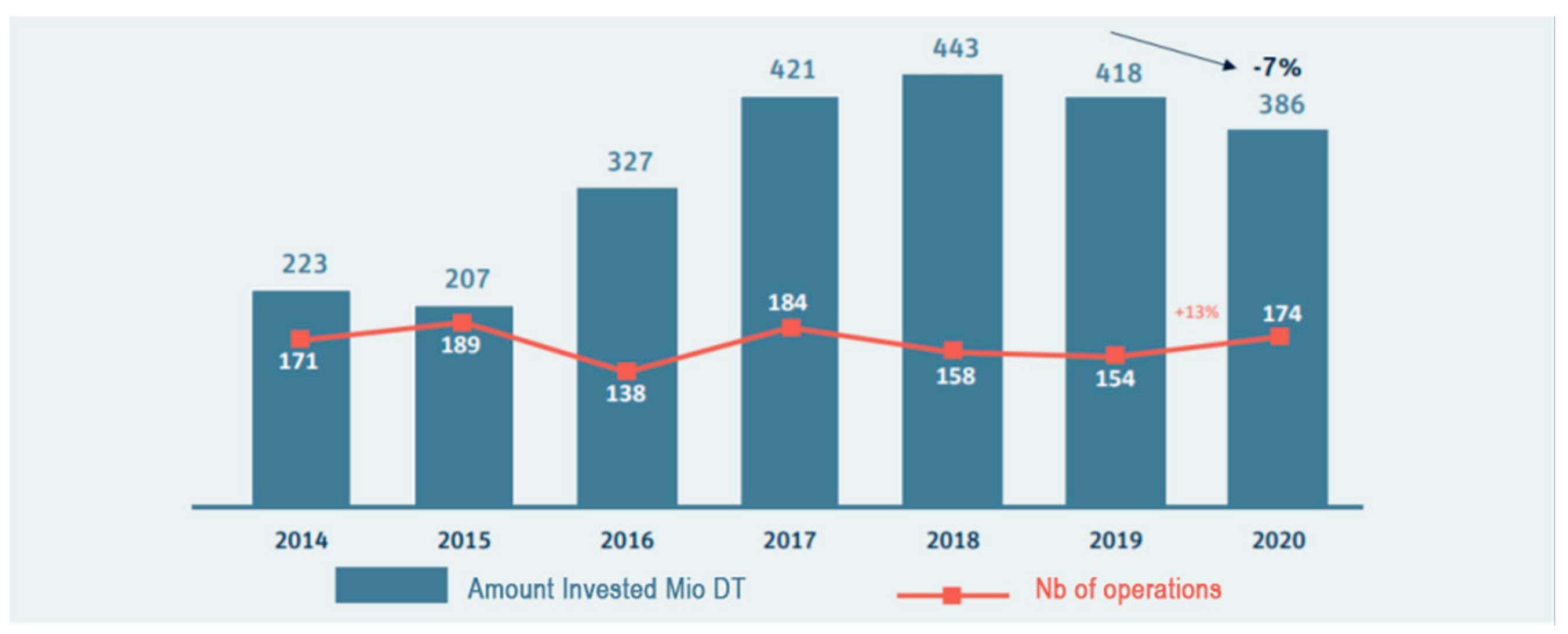

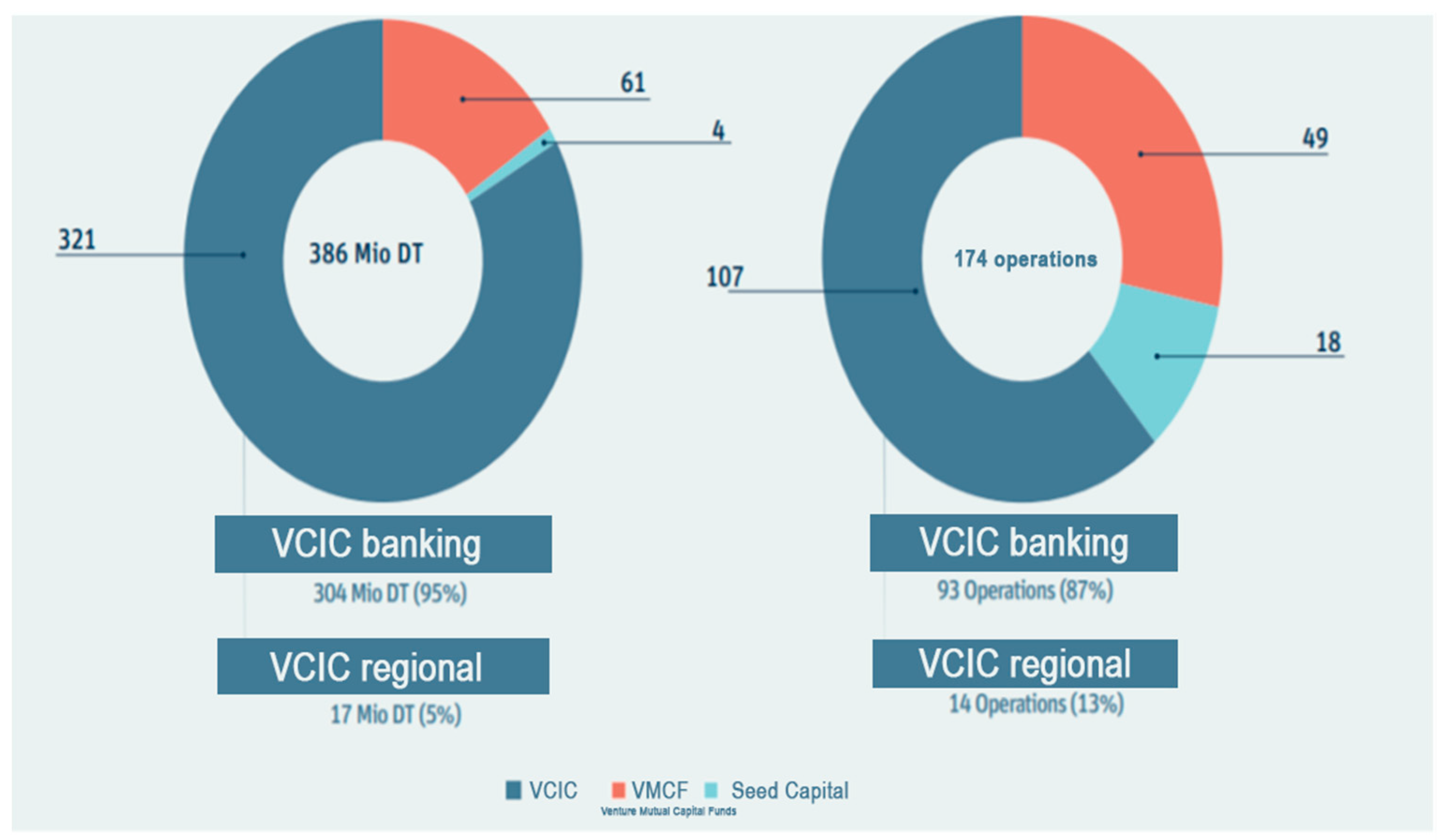

This critical year was marked by an increase in investments in the ceramic and glass building materials industries and in education, with figures showing a 110% increase in the first sector and a very significant 547% increase in the second (from 957 KDT in 2019 to 6200 KDT in 2020). Given the tax benefits granted to regional development zones, investors have devoted 50% of the amounts to them. Nevertheless, among the 174 companies financed in 2020 by private equity, start-ups only benefited from 18 projects. It should also be noted that the preponderant share of investments, whether in terms of amounts or number of operations, is dominated by Venture Capital Investment Company, followed by Venture Mutual Capital Funds and seed funds.

According to the 2020 annual report drawn up by ATIC, the private equity sector recorded a slight drop in financing (by 7% to 386 MD in 2020 compared to 418 MD in 2019) and approvals (by 9% to 435 MD in 2020 compared to 14% in 2019). These figures confirm that despite this difficult economic situation, the sector has continued to fulfill its role of supporting businesses and withstood the COVID-19 crisis. As shown in

Figure 3 belown, the 386 MD supported the financing of 174 companies.

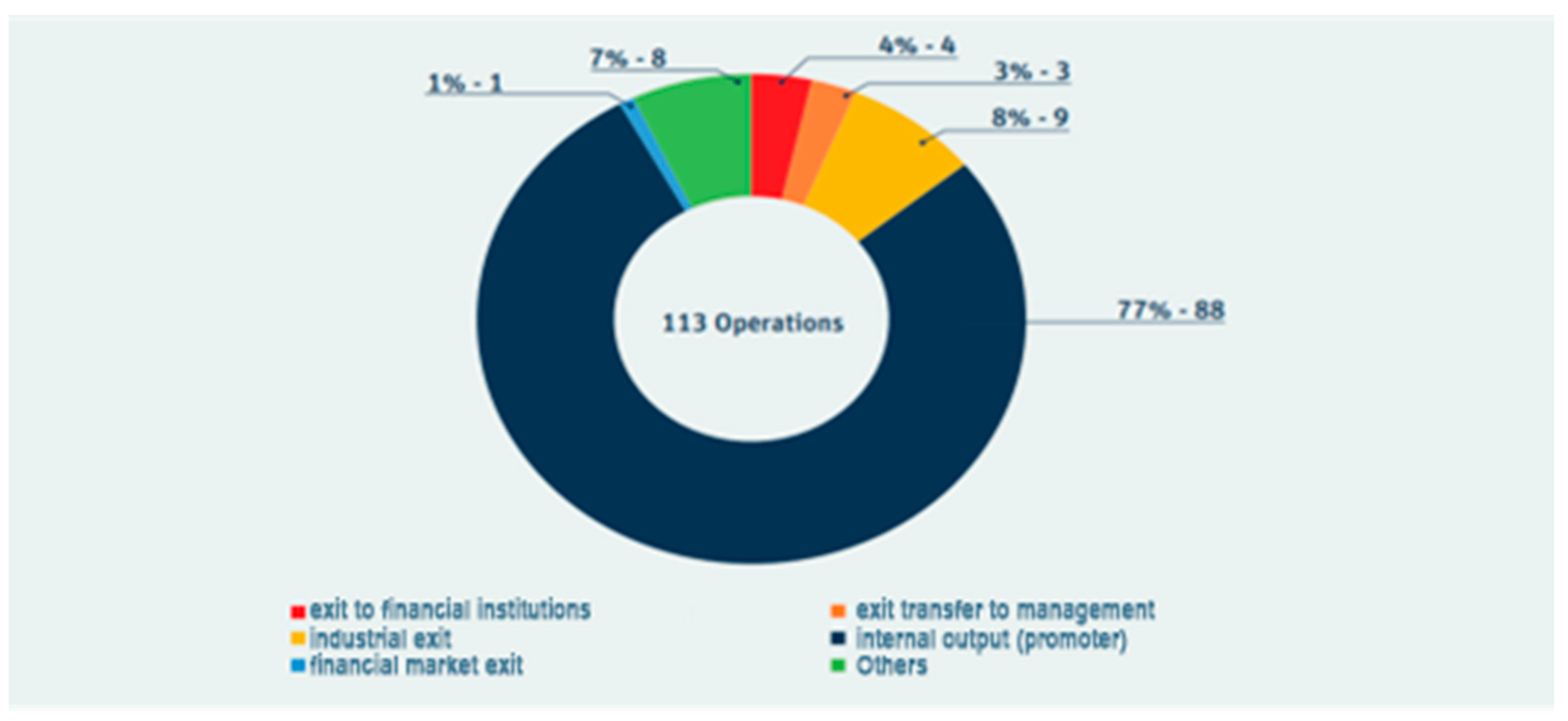

Thus, as shown in

Figure 4 below, 113 transfer operations were recorded under divestments for a total value of 112.2 MD, of which 54 MD were devoted to the education sector. Indeed, 77% of the total exit operations were carried out for the benefit of promoters (internal exit).

The private equity sector has shown strong resilience in this difficult moment, where it invested 397 million dinars in 2020 against 319 million dinars in 2019. However, most capital raised is predominated by local investors (99% Tunisian capital against 1% foreign capital). However, it is hoped that thanks to the adjustments made in the legal framework regulating the sector, these “outlying” values will improve in the coming years. Despite this important detail, the slight increase mentioned above is both proof of the dynamism of players in the sector and a sign of the attractiveness of Tunisian private equity.

Tunisia is only one example among the countries of the continent. Indeed, the African PE industry has shown signs of attractiveness over the past decades, even during the pandemic. The “2020 H1 African Private Equity Data Tracker” report testified to the resilience of the sector through funds raised and transactions concluded during the first half of the year.

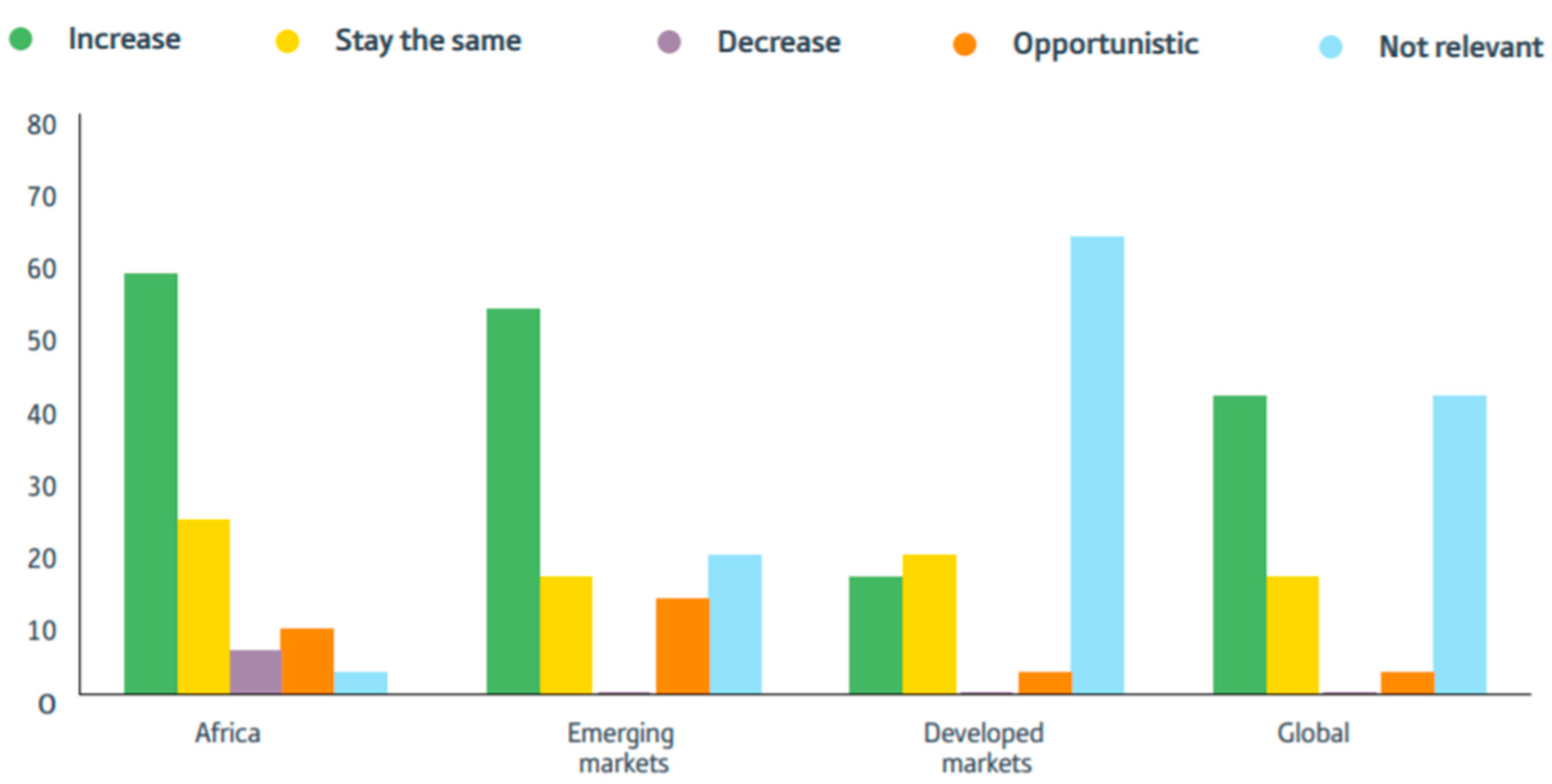

Figure 5 below shows the allocation plans for the African PE sector in 2020–2023.

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, we propose to study the selection criteria applied by Tunisian capital investors. Before presenting the results, we will detail the data collection method and the sample characteristics studied.

3.1. Methodology and Sample

The research method should depend primarily on the research question being asked. The broad purpose of this work is to analyze the criteria of private equity investment in emerging markets and, more specifically, to explore how different types of Tunisian private equity investors make investment decisions. Given the notable lack of research within these areas, a qualitative research approach seemed to be a good choice. Such a method provides a more holistic view of social dynamics, reduces the risk of oversimplifying the complexities of real-world phenomena, and is more likely to identify important factors that cannot easily be quantified (

Punch, 2005). More specifically, the methodological justification for making a qualitative study was to provide a rich and encompassing understanding of the phenomenon of study. This deepens our understanding of the investment criteria used by Tunisian private equity investors when making investment decisions.

In our case, the collective view of professionals will be helpful to prioritize the most important decision-making criteria. However, there is a lack of professionals in the region. This makes the number of respondents very small but reflects the reality of the Tunisian market.

Efforts were undertaken to interview key informants and the person in charge of the PE fund investment activities (

Barnes & Menzies, 2005). In other words, the respondents should all have a comprehensive understanding of their organizations’ way of managing PE investments. The respondents’ experiences from investing in the private equity sector are considered important criteria in the choice of target respondents. In our work, the more important thing is not the number of respondents but their experience and competence in the field.

The research methodology applied in our study aligns with those of

Desbrières and Broye (

2000),

Dhochak and Sharma (

2016), and

Mishra et al. (

2017) while studying investment criteria used by private equity investors. A questionnaire was constructed in order to collect all the necessary information to test our theoretical propositions regarding the relative importance of private equity investors’ investment criteria (See

Appendix A for the questionnaire). From the literature cited above, we applied a combination of sections: investment phases, intervention framework (or sector criteria), investment and target-specific considerations—including manager competence, target product market, exit horizon, and dividend yield rate—and general stock market conditions (

Block et al., 2019;

Eloranta, 2018;

Muhammad et al., 2017;

Tyebjee & Bruno, 1984). A pre-test was conducted, and the first version was sent to members of ATIC (Association Tunisienne d’Investissement en Capital) for validation. After that, it was improved by adding some additional criteria.

After the final validation, the questionnaire was sent again to target respondents (as explained above) by e-mail and via social networks (Facebook and LinkedIn). Of the respondents, 64.7% were in charge of private equity departments or were responsible for all alternative asset investments, and 35.3% percent of the respondents were CFOs (i.e., chief financial officers) with overall responsibility for the financial asset management within their organizations and held other senior management positions including the role of CEOs (i.e., chief executive officers).

Twenty-two usable responses were obtained out of the 51 questionnaires sent. Our response rate (43.13%) is above that reached by

Desbrières and Broye (

2000), who obtained 32 usable responses from 133 questionnaires sent, which means a response rate of 24%. However, our response rate is below that obtained by certain comparable studies (

Wright & Robbie, 1996), which testifies to the confidentiality of the Tunisian private equity sector and the significant cultural differences that may exist between different nations (

Hofstede, 1984;

Hampden-Turner & Trompenaars, 1993).

The qualitative approach allows for the exploration of the emotions, feelings, and personal experiences of the investors concerned, thus contributing to a better understanding of the impact of private equity in emerging markets.

Since the number of professionals was limited, we were obliged to incorporate experienced and knowledgeable people regarding private equity. These people were chosen on the basis of their experience and skills in the field.

We used PCA because it condenses data from many variables into just a few variables to make the results easier to understand.

3.2. Hypothesis Formulation

The object of this part is to test whether distributions of different items (presented in the questionnaire) are the same. Kendall’s and Friedman’s statistical tests were performed to attain this. Kendall’s W test, known as Kendall’s coefficient of concordance, is a non-parametric statistic for rank correlation. It is a normalization of the statistics of the Friedman test and is used to test the null hypothesis. In other words, they can be used to assess the trend of agreement among respondents and, in particular, inter-construct reliability.

Kendall’s W estimation process makes no prior assumptions about the nature of the data distribution but rather performs statistical calculations based on the ranking of the data.

As shown in

Table 1, according to both tests, we can reject the null hypothesis, which indicates that the distributions of the different items of our survey are not the same, and the respondents’ rankings are significantly different at a 5% level of significance.

3.3. Empirical Results

In this section, we will present the main results of the questionnaire on the key criteria for assessing private equity investment projects.

Respondents were invited to specify the contexts in which they invest, the phases in which they intervene most often, and the criteria they consider most important in the pre-selection phase.

Table 2 presents the intervention phases of the participants. For 100% of respondents, the development phase is considered a category in which it is essential to invest, followed by the restructuring phase (64.6%) and the transmission phase (53.1%). Finally, the start-up phase is ranked 4th with a percentage of 47.5%.

The analysis of the results on the intervention framework of our respondents shows that 82.7% of them prefer to operate in a free framework, followed by investments in innovative projects with a percentage of 70.8%.

Table 3 also shows that investors favor investment in the regional development zones (RDZs) of the 2nd group rather than in the regional development zones of the 1st group because of the tax advantages offered by the State in the 2nd zone. Indeed, the percentages of intervention are 53.1% in the RDZs of the 2nd group against 41.1% in the RDZs of the 1st group.

As shown in

Table 4, for Tunisian capital investors, two criteria are considered essential during the pre-selection phase: the characteristics of the target product market and the contribution of the managers in terms of competence (with percentages of 94% and 88.3%, respectively).

Then, we notice that the criterion of the financial contribution of managers is important for 59% of the respondents. However, the criterion of the anticipated exit horizon is considered to be crucial for 41.5% of them. Many investors consider the first criterion important because it can be considered as an agency variable: the higher the rate of participation of entrepreneur-managers in firm capital, the greater the convergence of interests between them and the investors. However, the weight of the exit horizon seems obvious: an extension of the exit horizon induces an additional risk for the investor who fears a drop in their profitability following a drop in the company’s performance.

Finally, the forecast dividend yield, general equity market conditions, and the anticipated horizon for the redemption of preferred shares are only considered important for 23.7%, 11.9%, and 5.7% of respondents, respectively.

3.4. The Most Important Information Source in the Project Selection Process

This part focuses on the prioritization of the individual information sources (components, items), as shown in

Table 5. A literature review is the basis for establishing this list.

Respondents were asked to indicate, for 17 information sources, the degree of importance of each of them, using a scale ranging from 1 (not important) to 5 (essential).

Table 5 shows the mean and the standard deviation for each item considered as a selection criterion in the decision-making process. The means were used to prioritize them. The components with the highest mean scores in

Table 5 are discussed below.

Analyzing the results separately, it can be seen that the most important criteria in the project selection process are the following: quality of information gathered from the interviews with entrepreneurs, information appearing in the balance sheet and income statement, product information, business plan and its overall consistency, information provided in due diligence reports, CVs of entrepreneurs, social accounts and finally information on production capacities and techniques. It should be noted that sales and marketing information, management forecast over one year ahead, exit horizon, interview with other staff members, one-year management forecasts, and industrial statistics are also important as their score is higher than 4.

Wright and Robbie (

1996) obtained the same individual score from British Cis as ours regarding the diligence report. On the other hand, the latter grants much less importance to the business plan and its coherence as well as to the second group information (interviews, product information, sales and marketing, projections, CVs of managers, etc.).

Furthermore, unlike the United States, where the characteristics of entrepreneurs represent one of the most important types of information for private equity investors, curriculum vitae and interviews with entrepreneurs only intervene respectively in the fifth and eleventh position for France (

Desbrières & Broye, 2000). This ranking, very close to that obtained in the United Kingdom (

Wright & Robbie, 1996), may indicate that the French private equity industry is, like its European counterparts, more oriented on financial criteria, as shown by

Sapienza et al. (

1996). However, the CV and interviews with managers obtain a score higher than 4, which means that even if they are not among the most valued sources of information, PE investors consider them very important, particularly in relation to British PE investors.

Accounting sources of information are also considered very important by Tunisian PE investors, especially the certified audit report, balance sheet, and income statement (scores largely greater than 4) in relation to audit reports and uncertified social accounts (high scores greater than 4), which is consistent with results found by

Desbrières and Broye (

2000).

Respondents were also asked about their preference for either certified reports issued by independent auditors or non-certified accounting information, i.e., those provided by the company’s management team. 100% of responses pointed to certified audit reports. This result can be explained by the fear of PE investors suffering information withholding or communicating a distorted version of important facts (

Sahlman, 1990;

Amit et al., 1993), which may mean that Tunisian PE investors experience greater information asymmetry or are more cautious. Generally speaking, it is striking to note the weakness of the standard deviation, which testifies to a great consensus among respondents on the sources of information.

3.5. Robustness and Reliability Using Principal Component Analysis

The next step of the exploratory analysis aimed to identify the most discriminating questions, their relationships, and the initial training of the respondents. A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was carried out for this purpose.

In our case, PCA allows us to test whether the existing measurement scale (which is the questionnaire) can be shortened to include fewer items (questions/statements), perhaps because such items may be superfluous (more than one item may be measuring the same construct). It is a statistical technique that combines related questions (correlated) into a smaller number of factors to create more robust measures.

By combining questions and using the resulting measures rather than analyzing and reporting them individually, this technique is useful as a dimensionality-reduction technique, and being based on correlations can help avoid some of the problems of collinearity that can arise in analyses. Additionally, by capturing overall dynamic characteristics and qualities rather than individual or separate items, factors/axes can often provide more meaningful results.

The first step in PCA is to calculate the correlations between each of the items. After that, the appropriate number of factors (axis) to be extracted is determined, and factor solutions are calculated based on the correlations. It groups together questions that are highly correlated to derive a smaller set of factors that retain a high proportion of the information in the original questions.

In our case, data from the completed questionnaires were initially captured on an Excel spreadsheet, after which the latest SPSS software (SPSS 27) further analyzed it. These quantitative data from Part 2 of the questionnaire were first analyzed descriptively to establish the mean and standard deviation of each of the 17 components/items. PCA was applied to show which of these individual criterion items “go together”. Therefore, the components were loaded into four initial constructs through initial exploratory PCA.

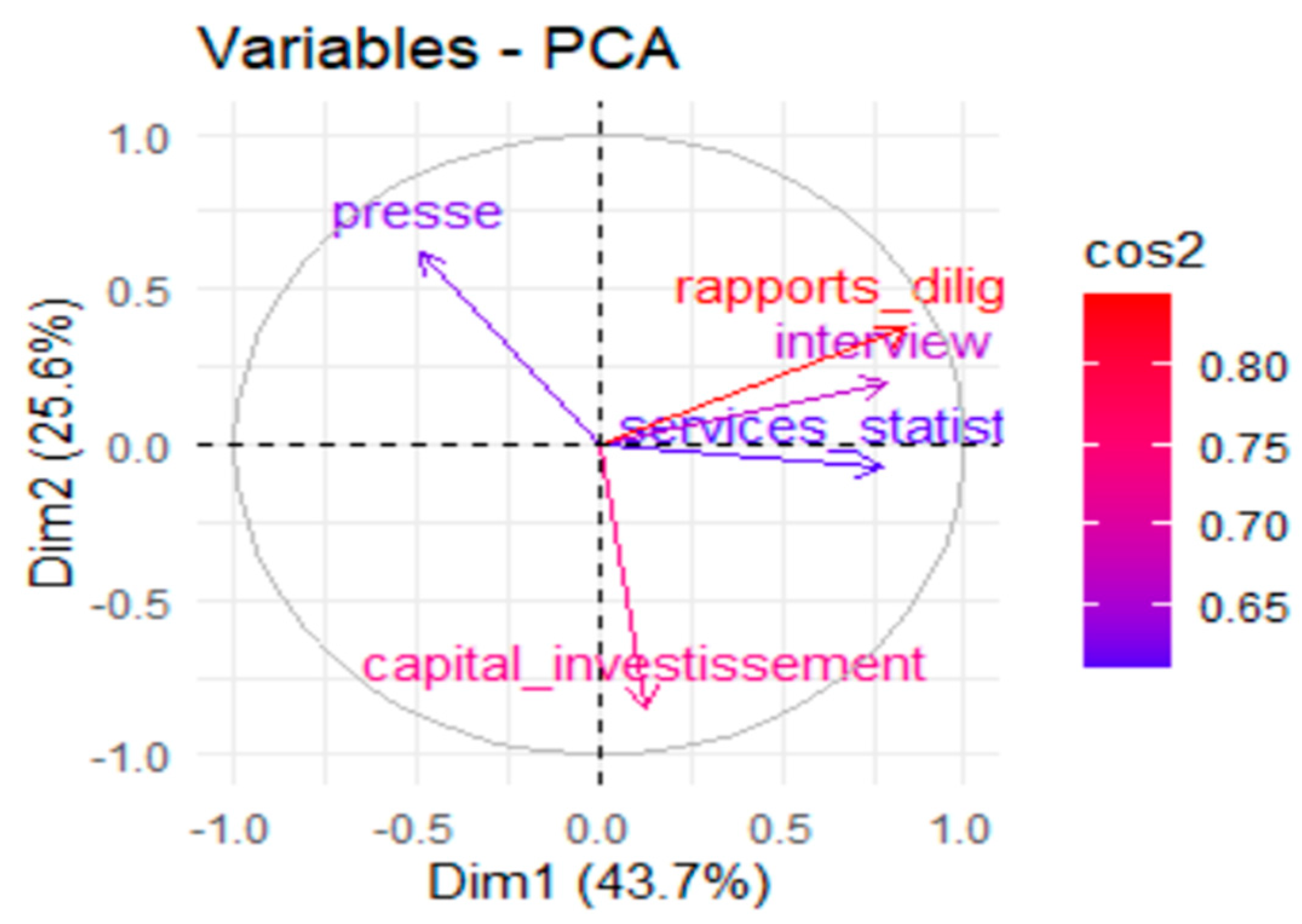

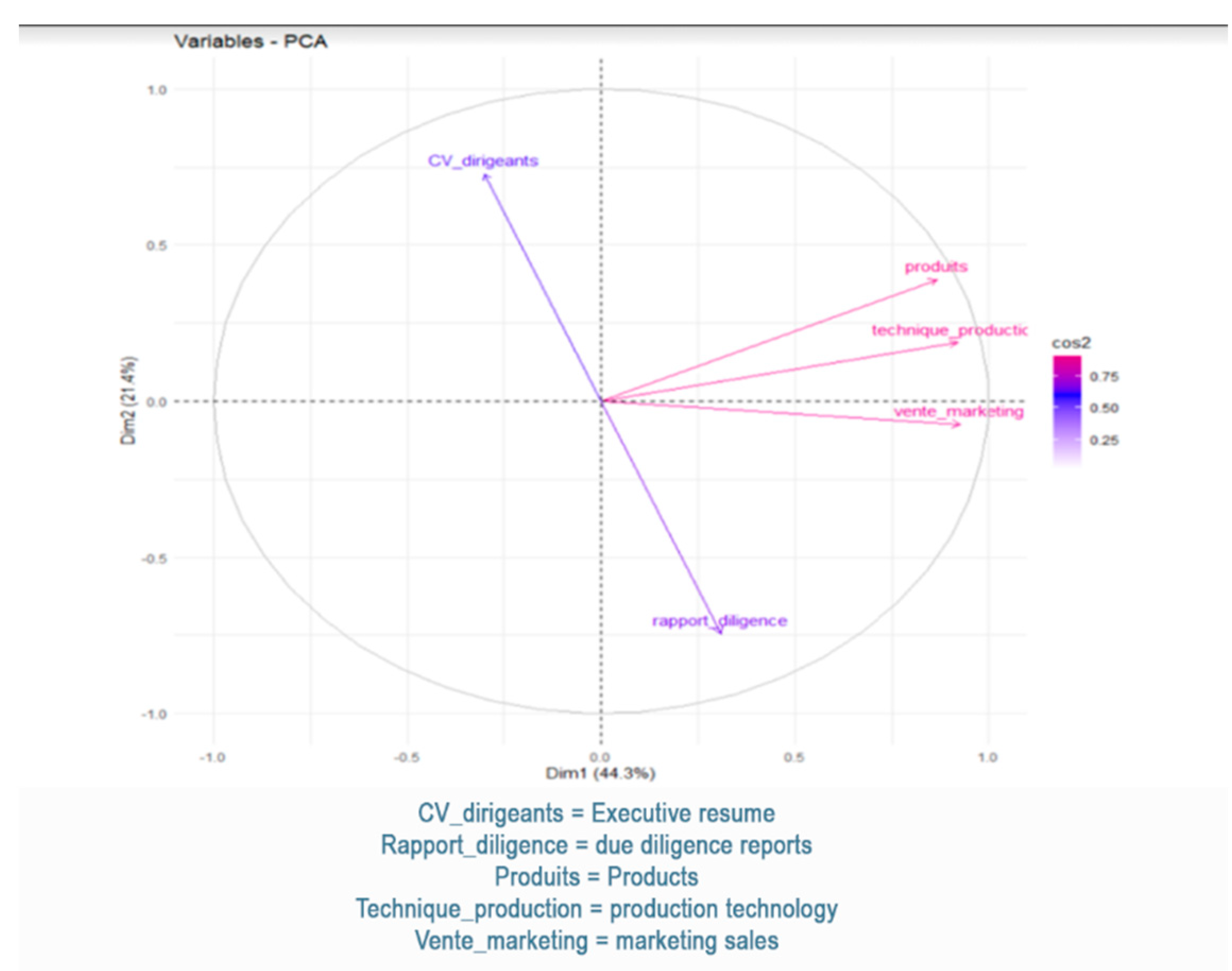

As shown in

Table 6, eigenvalues were calculated to determine the number of factors included under the factor’s ability to assess private equity projects. Four factors were identified and renamed, which explain 22.54%, 17.49%, 14.58%, and 12.05% of the variance, respectively. Descriptive statistics are also presented; the construct’s mean can be used to determine the relative importance of the construct.

Finally, Cronbach’s alpha was used to test for construct reliability, as shown in

Table 6. Reliability allows us to evaluate the ability of the instrument to measure consistently. Cronbach’s alpha indicates the internal consistency of the construct (reliability), which it expresses as a number between zero and one (

Tavakol & Dennick, 2001). According to the construct tested, different results could be judged to be appropriate. For example,

Field (

2009) states that whilst a value of 0.8 is appropriate for an intelligence test, values of 0.6 and 0.7 are acceptable for ability tests. Finally, to determine each of the individual criteria items and the newly found constructs, descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were calculated, and the mean values were used to rank them. The reliability of the four constructs is confirmed.

The results of the 17 components in Part 2 of the questionnaire, which tested the views of the respondents on how they assess PE investment, are presented in

Table 5. The mean value and standard deviations are presented for each component. The second objective is hereby accomplished as this table implies that the higher the individual criteria items’ mean values, the higher their relative importance. PCA was used to analyze the 17 components of Part 2 of the survey questionnaire.

We obtain four axes. The interpretation of these axes is simple. They characterize the general information (essentially external), accounting information, extra-accounting information, and the business plan. As the analysis of these sources of information taken individually could suggest, the degree of importance of this axis is increasing. The information provided by the business plan is considered almost essential by the PE investors, with that grouped in the other axis being, on average, considered important (Axis 3 and 2) and moderately important (Axis 1) (See

Figure 6). Obviously, disparities exist between the sources of information grouped in each axis, and the analysis of the PCA must not be dissociated from the different sources of information taken individually.

Moreover, the 2nd axis, that of accounting information, social accounts, and certified audit reports, is more valued by Tunisian capital investors (mean = 4.82). This is explained by the fact that most of the projects financed tend to be development investments and LBOs for which historical accounting data are available. This, therefore, makes it possible to confirm the consistency between the results already found.

Finally, it would be appropriate to note that the information collected from external sources (such as financial press, other private equity firms, and government statistics on the sector) is the least appreciated by Tunisian investors.

Figure 7 shows a very important finding: variables grouping information provided by the financial press and those collected from other private equity organizations are inversely correlated, i.e., if an investor chooses financial information, it will certainly undermine those coming from other organizations. The other criteria positively correlate.

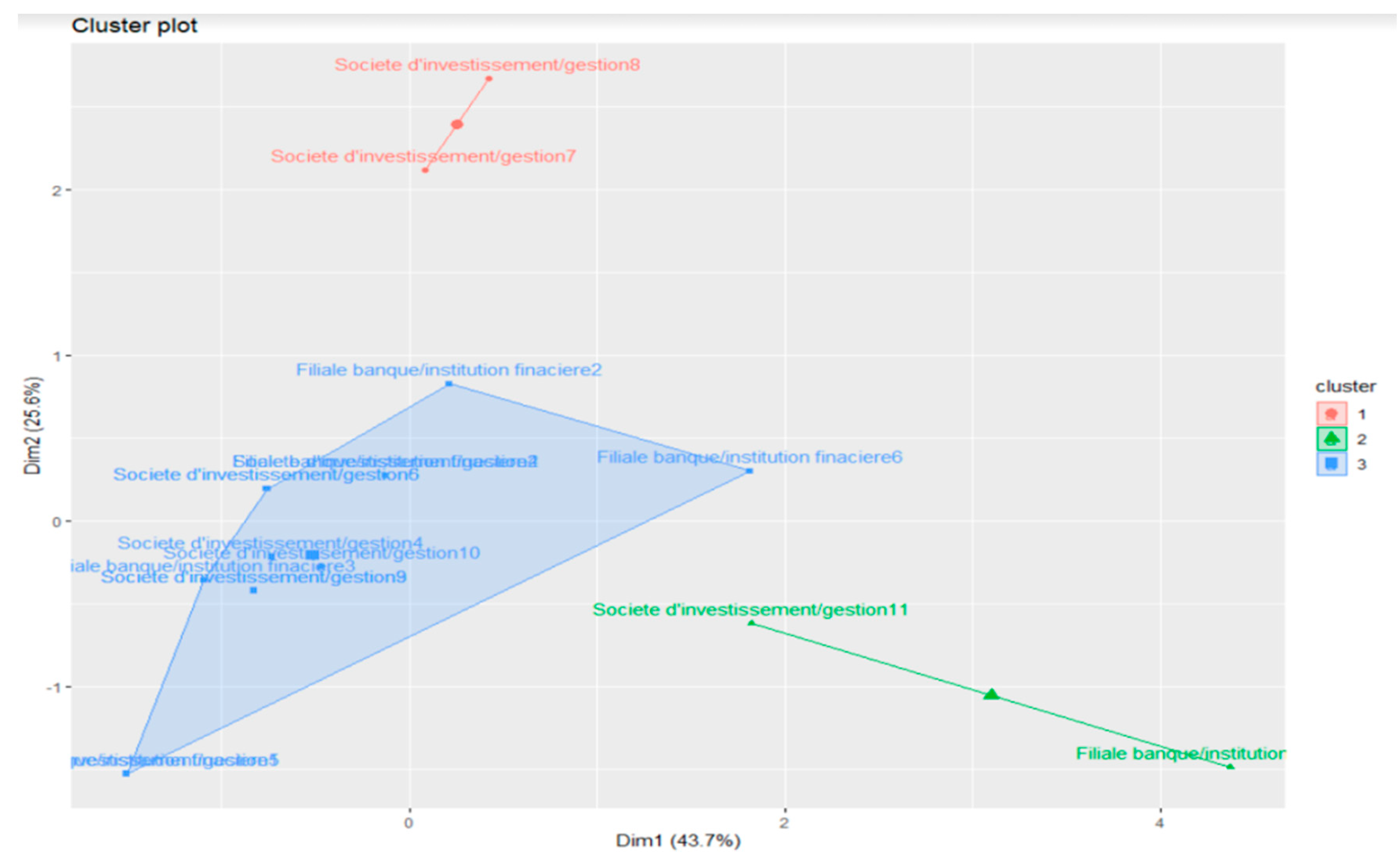

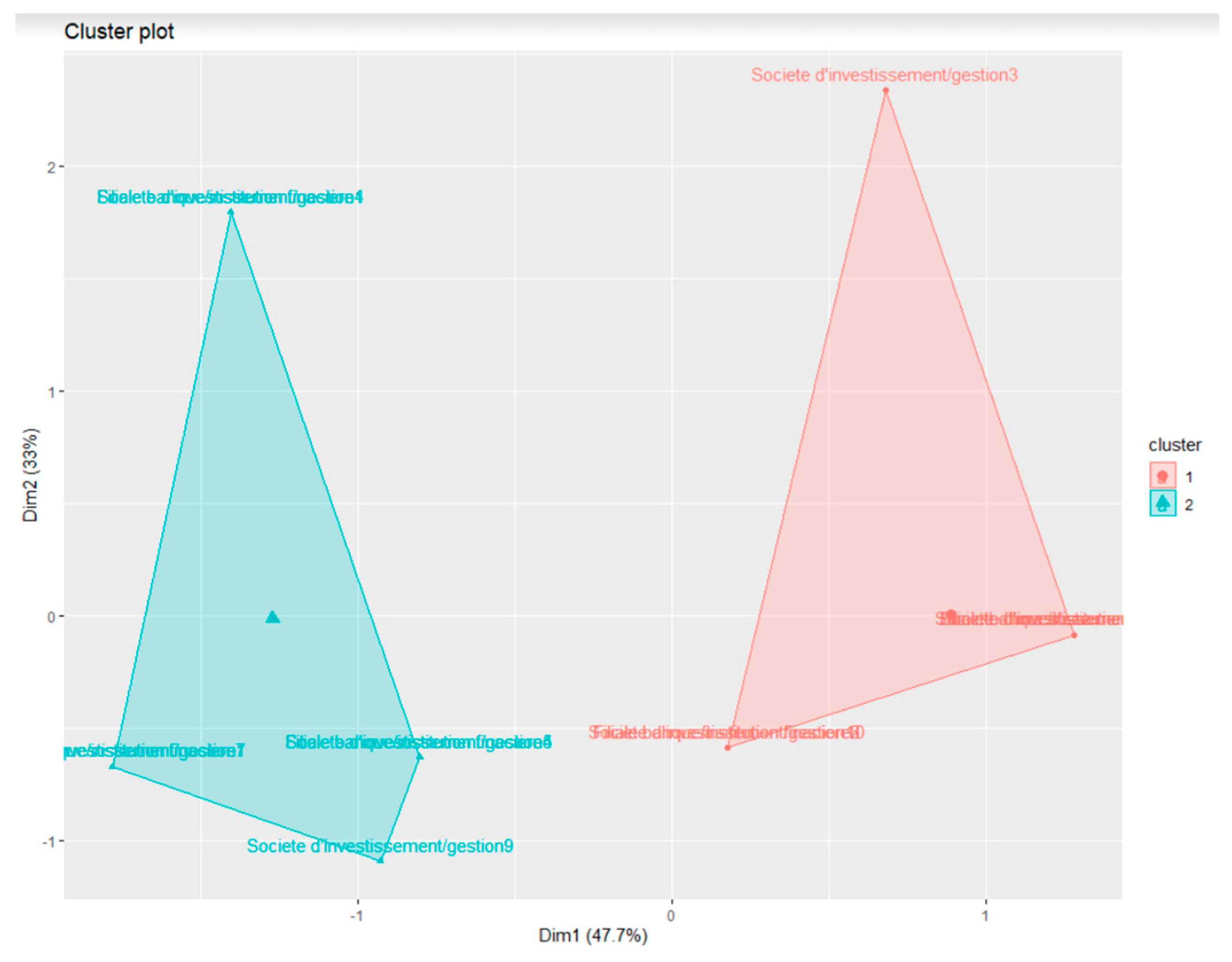

This figure groups the respondents according to the category to which they belong. From the figure above, it can be seen that most respondents provided similar answers on the first axis of the questionnaire (the blue geometric shape), while the other two groups (the red and green lines) each reflect the resemblance of the responses of only two investors.

Figure 8 shows that the variables of the first axis positively correlate while those of the second axis inversely correlate, i.e., if an investor gives more weight to the CVs of entrepreneurs, they will give less value to the diligence report.

For Axis 4,

Figure 9 indicates that respondents can be classified into two categories. Each includes all of the respondents who gave similar answers.

4. Conclusions

Our study sheds light, for the first time, on the investment criteria used by Tunisian private equity investors when making investment decisions. The collective vision of professionals was useful in prioritizing the most important decision criteria.

Within the framework of the conceptual paradigm according to which the institutional environment can influence investment criteria, the interest of the study is that the different stakeholders can benefit from a better understanding of the priority of the aspects that affect the decision of the Tunisian private equity investors.

Our article presents three theoretical and two practical contributions. The first theoretical contribution is to demonstrate the unique nature of private equity when practiced in emerging countries. As such, we suggest that this segment will continue to grow in favor of macroeconomics, geopolitics, and the global crisis—which specifically affects advanced economies and encourages geographic arbitrage favorable to emerging regions.

The second theoretical contribution is to propose a broad and multidimensional definition of the notion of emergence, characterized by significant turbulence and high potential. This notion encompasses societal emergence (start-ups), technological emergence (ICT and biotechnology), and macroeconomic emergence (emerging countries).

The third theoretical contribution consists of an in-depth review of the literature on private equity in emerging countries.

In addition to these three theoretical contributions, two practical contributions can be drawn from our work. The first practical contribution is to provide recommendations to management companies operating in emerging countries, both in terms of the composition of the management team and subscribers and the nature of the internal operational process “investment–monitoring–exit”.

The second practical contribution is to provide an up-to-date overview of emerging countries (in macro and microeconomics) and the practice of private equity in these countries beyond the hype regularly reported by the press and major research firms.

In order to fully understand the criteria when selecting investment projects, we interviewed several Tunisian capital investors using a questionnaire. The response rate was 41.46%. The questionnaire results concluded that 100% of investors tend to invest in companies that aim to achieve some growth and are in the development phase.

Thus, the most important conclusions drawn from the results are that Tunisian investment companies give more weight to business plans, information provided during interviews with entrepreneurs, and product information.

After analysis of empirical data, the results show that in the context of informational asymmetry between entrepreneurs and investors, the latter attaches greater importance to the business plan drawn up by the managers, information gathered during interviews with entrepreneurs, and product information. These results support the “internal information” hypothesis, which suggests that sophisticated investors, especially specialized private equity firms, are more inclined to use “soft” (internal) information to assess the competence of the CEO and to decide on their investments.

This study provides practical information for investors in Tunisia. Specifically, it helps investment companies to present the process of handling an investment file and to examine the project selection criteria used by Tunisian equity investors. In the context of informational asymmetry between investors and entrepreneurs, these investment companies give greater weight to business plans drawn up by management. In such a context, this study encourages investors to use certified audit reports, demonstrating the importance of accounting information in this process. This result supports the control theory, which states that private equity-backed firms exercise more active monitoring and stricter control. Indeed, the more concentrated ownership structure of private equity-backed firms leads to stronger shareholder control and more frequent CEO replacement in the event of poor performance than the dispersed ownership structure of listed firms.

This study could also benefit companies looking to attract funding from private equity investors. This prioritized list will aid in organizing themselves to become attractive investment opportunities. Furthermore, Tunisian private equity investment professionals can use the results of the study to assess their current practices. Results will aid in benchmarking their investment decision-making practices against the collective view of professionals.

With these findings, our work can make a contribution to the corporate finance literature by deepening our comprehension of how different types of private equity investors make investment decisions.

However, our article has three limitations. The first aspect of this work consists of a case study of emerging countries. Indeed, the study could be improved by considering new clinical cases of investment funds in emerging countries: this would allow, again using an inductive approach, to support or clarify certain contradictions in the Tunisian case study that underlies our work. If we had taken other emerging countries, we would have had to identify other important factors that could influence investors’ decisions.

A second limitation lies in the nature of the companies in our sample. Indeed, we need to increase our understanding of SMEs in emerging countries by taking into account their nature as family businesses.

Finally, a limitation of the study is that only 41% of those contacted responded to the questionnaire, which testifies to the confidentiality of the Tunisian private equity sector and the difficulty of collecting the contact details of its players.

In order to guard against information asymmetry or misrepresentation of data, investors, therefore, use certified audit reports in their analysis, which affirms that accounting information also plays a very important role in this process because most investments in Tunisia are devoted to development or LBOs.