Abstract

This study highlights the pivotal role of women in corporate governance and their potential influence on achieving sustainable goals, particularly in the context of emerging countries. Using the two-step System-Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) with the dynamic short panel data of 351 nonfinancial listed companies in Vietnam from 2010 to 2022, this research examines the dynamics between earnings management and tax avoidance, focusing on the moderating role of women on the board of directors. The results confirm that both accrual-based and real earnings management are positively associated with corporate tax avoidance. However, there is a significant negative relationship between female representation on the board and tax avoidance, as well as a significant moderation of the relationship between earnings management and tax avoidance. This study reinforces that female leadership contributes to reducing earnings management and tax avoidance through improved monitoring and governance of corporate ethical activities, emphasizing the importance of strategically empowering women in leadership roles. The implications of this study are given to minimize harmful financial practices and align corporate strategies with ethical practices.

1. Introduction

The relationship between earnings management and corporate tax avoidance has attracted growing attention in the corporate finance and governance literature. Earnings management, often regarded as a managerial tool to influence reported financial performance, can serve both beneficial and opportunistic purposes. On the one hand, it may help firms smooth earnings and signal stability (Chauhan & Jaiswall, 2023; Krystyniak & Staneva, 2023); on the other, it can be used to manipulate income and take advantage of tax loopholes to reduce tax obligations, known as tax avoidance (Chen et al., 2025). Under the lens of agency theory, managers incentivized by performance-linked compensation may use earnings management as a vehicle for tax minimization, reflecting a conflict between managerial self-interest and shareholder value (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). This view is supported by numerous studies that have demonstrated that earnings management is often aligned with aggressive tax strategies (e.g., Chen et al., 2025; Amidu et al., 2019). However, contrasting arguments suggest that earnings management does not always facilitate tax avoidance. For instance, firms engaging in certain forms of earnings management may inadvertently increase their effective tax burden (Richardson et al., 2016b), and some types of real earnings management have been associated with reduced levels of tax avoidance (Wang & Mao, 2021). These contradictions suggest that the assumption of a universally positive link between earnings management and tax avoidance may be contingent on various factors.

In parallel, the role of female directors on corporate boards has emerged as a critical area of interest, particularly regarding their influence on financial reporting quality and tax planning. Female directors are theorized to improve board effectiveness through ethical orientation, prudence, and enhanced monitoring capabilities (Kwamboka et al., 2025; Hossain et al., 2024). According to agency theory, female directors contribute to improved oversight, ethical judgment, and risk aversion, which may restrain managers from engaging in earnings management or tax avoidance (Amin et al., 2021; Bart & McQueen, 2013). Likewise, political cost theory suggests that gender-diverse boards improve transparency and accountability, helping firms avoid reputational and regulatory risks (Bazel-Shoham et al., 2024; Tseng et al., 2020; Damayanti & Supramono, 2019). Resource dependence theory further posits that female directors enhance firms’ legitimacy and access to external resources (Hillman & Dalziel, 2003). Despite these theoretical assertions, empirical findings remain inconsistent. While several studies support the view that female board participation reduces both earnings management and tax avoidance (e.g., Zhang et al., 2022; Richardson et al., 2016a), others report insignificant or even positive associations (Suleiman, 2020; Oyenike et al., 2016). These discrepancies highlight the possibility that the effectiveness of female directors depends on contextual factors such as the institutional environment, enforcement mechanisms, and the nature of the firm’s governance structure. For instance, in emerging markets where gender bias and concentrated ownership persist, female directors may lack the authority or necessary independence to influence financial decision-making meaningfully (Anita et al., 2024; Mobbs et al., 2021).

This contextual variation underscores the importance of extending research into emerging economies, where both governance systems and gender inclusiveness are still evolving, such as Vietnam. In Vietnam, corporate scandals involving earnings management and financial misreporting have raised concerns about managerial opportunism and the effectiveness of board oversight (Q. Nguyen et al., 2024; T. K. Tran et al., 2023). Furthermore, Vietnam’s enterprises are characterized by concentrated ownership, limited enforcement, and insufficient gender inclusion in leadership roles (N. H. Tran & Le, 2020; H. A. Nguyen et al., 2021), making it a suitable case for examining whether female directors can constrain aggressive financial behaviors such as earnings management and tax avoidance. Moreover, corporate income tax often accounts for a large proportion of the total tax revenue in developing countries, thereby playing a strategic role in mobilizing financial resources to serve economic development goals. Additionally, prior research has largely examined these issues in isolation without exploring how female board representation may moderate the relationship between earnings management and tax avoidance. In such a setting, investigating the moderating role of female directors in the earnings management-tax avoidance nexus is both timely and necessary. It enables scholars and policymakers to assess whether promoting board gender diversity in emerging markets can serve as an effective tool for improving financial integrity and reducing opportunistic behaviors.

To address these gaps, this study investigates the influence of earnings management on tax avoidance and the direct and moderating role of female directors in the link between earnings management and tax avoidance. Drawing on agency theory, political cost theory, and resource dependence theory, this study examines how internal governance structures shape corporate tax behavior in the context of Vietnam. Using a sample of 351 nonfinancial listed firms from 2010 to 2022, the study employs the System-Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) to control for endogeneity and dynamic effects, consistent with the approaches of Arellano and Bond (1991) and Arellano and Bover (1995) and recent applications in tax research (Hlel, 2024; Sani et al., 2024; T. K. Tran et al., 2023; Khuong et al., 2019). This study makes several contributions: First, it extends the prior research by jointly analyzing the impact of earnings management and board gender diversity on tax avoidance, highlighting the interdependence of financial reporting and governance mechanisms. Second, it adds empirical evidence from a transitional economy, offering insights into how female leadership can enhance financial accountability in environments with weaker regulatory systems. The influence of female leadership on earnings management and tax avoidance is not universally consistent but appears to be mediated by broader cultural, institutional, and organizational factors. Third, the study provides policy-relevant findings that support the promotion of gender diversity as a tool for improving governance transparency. Understanding these dynamics is essential for designing governance reforms that are both equitable and effective in advancing sustainable corporate behavior. Lastly, the study contributes to the discourse on sustainable development, specifically in relation to “Gender Equality” (SDG5) and “Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions” (SDG 16), by demonstrating how ethical leadership and board diversity can reduce harmful financial practices and support responsible corporate behavior.

In addition to Section 1—the introduction—the rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the debate around relevant theories and research and proposes some hypotheses. Section 3 presents the background, econometric model, data, and estimation methods. Section 4 presents the main results and discussions, while Section 5 provides a summary of the main conclusions, implications, and limitations of this study.

2. Literature Review

This section discusses theories and empirical studies that describe the role of female involvement on boards of directors and how the presence of women affects earnings management and tax avoidance behavior.

2.1. Theory Review

The first pillar of this study—agency theory—articulated by Jensen and Meckling (1976), explains the conflicts between principals (shareholders or owners) and agents (managers), which arise primarily from divergent interests and information asymmetry. According to agency theory, managers may prioritize personal gain over shareholders’ welfare, especially when their incentives are misaligned with firm interests; hence, shareholders usually implement incentive and monitoring mechanisms to mitigate such agency problems. Agency theory effectively describes how managerial incentives influence earnings management and tax avoidance behaviors. According to Desai and Dharmapala (2009), when managerial compensation—such as bonuses or stock options—is linked directly to financial performance, managers are incentivized to pursue aggressive tax avoidance strategies to enhance reported earnings, often ignoring potential long-term risks. Consequently, tax avoidance becomes intertwined with earnings management, as managers manipulate accounting practices (e.g., transfer pricing, cost allocation, and revenue recognition) to artificially inflate profits, maximize bonuses, or bolster their financial reputations (Kovermann & Velte, 2019; Amidu et al., 2019). Such managerial actions clearly illustrate the principal-agent conflict: managers may prioritize short-term personal gains even when such actions harm long-term shareholder value (Goh et al., 2013). Thus, the effectiveness of shareholder monitoring and the incentive structures set by corporations profoundly affect managers’ behavior. If monitoring is weak or compensation is insufficiently aligned with long-term outcomes, managerial opportunism can become prevalent, exacerbating conflicts and damaging firms’ sustainable goals (T. K. Tran et al., 2023).

Itan et al. (2024) suggested that corporate governance is a crucial factor influencing earnings management and, furthermore, that gender diversity is becoming critical in effective corporate governance. Increasing gender diversity, particularly through female participation on the board of directors, significantly alleviates agency problems (Wellalage & Locke, 2018; Matsa & Miller, 2013). Diverse boards exhibit improved monitoring and transparency, effectively reducing agency costs (Hossain et al., 2024; Amin et al., 2021). The presence of women on boards disrupts entrenched power dynamics, enhances the governance pillar, prevents domination by any individual or group, and promotes balanced decision-making (Zharfpeykan & Bai, 2025). Previous research showed that female directors often function independently from established male networks, enhancing their effectiveness as monitors with great communication skills (Alhossini et al., 2024; Oino & Liu, 2022). Female directors also adopt more cautious, risk-averse decision-making (Srinidhi et al., 2011), make consistently fair decisions when competing interests are at stake (Bart & McQueen, 2013), and advocate for rigorous auditing practices (Bona-Sánchez et al., 2024). These qualities are particularly vital in curbing earnings management, thus indirectly mitigating aggressive tax avoidance. However, it has also been argued that female directors tend to be less active and exhibit more emotional behavior than male directors (Chadwick & Dawson, 2018; Martinez Jimenez, 2009), which can lead to conflict among directors and increase potential costs for the firm (Wellalage & Locke, 2013). Furthermore, greater gender diversity among board members creates more questions and, again, more conflict, leading to more time-consuming and less effective decision-making (Ferrary & Déo, 2023). Gender diversity, therefore, emerges as a governance paradox in emerging markets: while traditionally overlooked or undervalued, female leadership within new corporate governance structures significantly enhances monitoring, reduces biases, and mitigates opportunistic managerial behavior.

In the second pillar of this study—political cost theory—Watts and Zimmerman (1983) asserted that large, profitable firms attract heightened public and governmental scrutiny, leading to significant costs, including increased regulatory oversight and higher financial burdens. Due to their visibility, these firms strategically adopt conservative accounting practices to lower reported profits, thus minimizing their exposure to political costs (Patten & Trompeter, 2003). Corporate income taxes exemplify such political costs, particularly for prominent companies facing higher Effective Tax Rates (ETRs), inherently reducing firms’ capacity to engage in aggressive tax avoidance (Zingales, 2017). Within this framework, earnings management serves as a strategic tool for influencing taxable income. Managers selectively adjust accounting figures to cautiously reduce reported profits, mitigating political scrutiny without significantly harming the firm’s reputation or attracting undue regulatory attention. Consequently, firms facing higher ETRs strategically manage earnings to diminish taxable income, effectively reducing their political costs related to taxes (Belz et al., 2018). Although political cost theory primarily addresses political scrutiny and cost minimization through earnings management, introducing gender diversity within corporate governance structures adds an interesting dimension.

Female leadership, characterized by enhanced ethical standards and a stronger emphasis on corporate transparency, may moderate earnings management behaviors by demanding clearer accountability and stricter adherence to regulations (Bazel-Shoham et al., 2024; Mensah & Onumah, 2023; Damayanti & Supramono, 2019). The presence of women on the board of directors is believed to contribute to reducing the risk of financial statement manipulation, as they tend to behave more honestly and prudently and demonstrate more independent thinking (Riguen et al., 2020; Richardson et al., 2016a). The intersection between gender diversity and political cost theory reveals an intriguing paradox: while female directors tend to reduce tax avoidance and earnings management (i.e., reduce managers’ benefits), their ethical oversight and prudent decision-making align well with firms’ broader strategic goal of minimizing their costs (Kwamboka et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2022). In other words, female leadership, though potentially limiting aggressive financial strategies, contributes positively by fostering responsible governance, thereby helping firms manage both political scrutiny and tax obligations. Thus, through enhanced corporate governance, female leadership emerges as a crucial factor in reconciling the tensions between earnings management and tax avoidance strategies under the lens of political cost theory in emerging markets.

In the third pillar of this study—resource dependence theory—the board of directors serves not only as a governance mechanism but also as a critical strategic link between the firm’s development and its external environment (Tan et al., 2025). A gender-diverse board, particularly one featuring the inclusion of female members, significantly strengthens this strategic linkage, improving the firm’s access to vital external resources and reinforcing its legitimacy among stakeholders and the public (Hillman & Dalziel, 2003; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). Female directors play a crucial role in addressing stakeholder expectations regarding external legitimacy, positioning them effectively to satisfy societal norms that call for greater gender diversity on corporate boards (Mukherjee & Krammer, 2024). Such relationships significantly boost the firm’s reputation, enhance legitimacy, and positively influence its public image (Tseng et al., 2020; Gulzar et al., 2019). Moreover, female leaders’ sensitivity to ethical standards and legal risks often deters management from short-term, aggressive tax avoidance strategies through earnings management (Zhang et al., 2022; Richardson et al., 2016a). Hence, while aggressive earnings management might offer short-term financial benefits through tax avoidance, the presence of women on boards offers ethical and governance benefits and strategically positions the firm to sustain and strengthen vital external relationships.

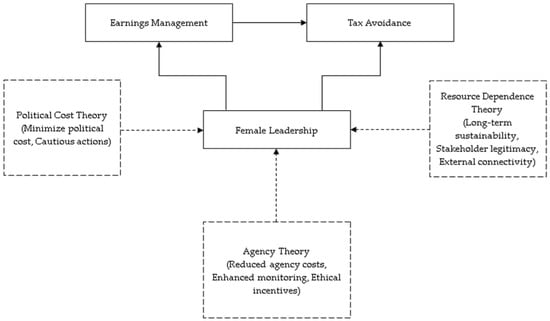

Therefore, this intersection of gender, governance, earnings management, and tax avoidance clearly illustrates the complex yet crucial role of female leadership in strengthening corporate governance. The presence of women on boards not only offers ethical and governance benefits but strategically positions the firm to sustain governance practices. However, this is not without controversy. While agency theory emphasizes that female leadership can contribute to reducing conflicts of interest between shareholders and managers, thereby reducing agency costs, it also allows them to engage in more sophisticated financial practices that are difficult for stakeholders to detect. Furthermore, although female leadership is viewed as a strategic resource, as per resource dependence theory, capable of expanding the network of relationships, increasing access to diverse resources, attracting greater attention from the public and management agencies, and providing opportunities to improve corporate image and enhance legitimacy, it is also possible, as per political cost theory, that firms may use the image of female leadership as a shield and that social expectations of female leadership ethics may serve to camouflage complex tax avoidance strategies employed to reduce political risk. Together, these three theories illustrate the different (and perhaps opposing) roles of female leadership in corporate financial strategies. The ongoing debate, both theoretical and empirical, suggests the need for further research, especially in emerging countries, which are characterized by male-biased governance and power concentration. The following section presents previous studies on this topic and analyzes the pros and cons of female leadership concerning tax avoidance and earnings management. Figure 1 shows the relationship between female directors, earnings management behavior, and tax avoidance (arrowed lines) from the perspectives of relevant theories (dashed lines).

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

2.2. Previous Study Review and Hypothesis Development

Previous research has examined corporate tax avoidance and earnings management separately, primarily investigating their determinants independently (e.g., T. K. Tran et al. (2023), Khuong et al. (2022), Thu et al. (2018), etc.). However, there is relatively limited but growing empirical interest in understanding the interplay between these two phenomena. Recent evidence supports the idea that managers frequently engage in earnings management specifically to facilitate corporate tax avoidance strategies. For example, Amidu et al. (2019) explored firms in Ghana between 2008 and 2015, specifically linking earnings management and transfer pricing to corporate tax avoidance. The study found substantial evidence supporting the role of managers as self-interested agents engaging in earnings management to reduce corporate tax liabilities. This aligns strongly with agency theory, which argues that managerial self-interest often leads to decisions that are detrimental to shareholder value. Similarly, Thalita et al. (2022) conducted an empirical investigation on 234 companies in Indonesia from 2016 to 2020, introducing political connections as a moderating factor. The study reinforced the hypothesis that earnings management positively and significantly enhances corporate tax avoidance behavior. Crucially, politically connected firms showed even stronger incentives, suggesting that political ties amplify managers’ motivation to leverage earnings management for tax avoidance purposes. As highlighted by Hlel (2024), using data from 323 French companies from 2010 to 2017, tax avoidance has a positive relationship with earnings management, consistent with agency theory and political cost theory. The authors emphasize that a lack of supervision and discretion in financial preparation and disclosure leads to opportunistic behavior and portrays the financial situation to be more favorable than it actually is.

However, contrary evidence comes from Richardson et al. (2016b), who similarly studied Chinese firms from 2005 to 2010 using a robust sample of 1242 observations. The authors measured tax avoidance through the ETR and the book-tax gap, with earnings management assessed via discretionary accruals based on Dechow et al.’s (1995) model (1995). Contrary to common expectations, their results suggested that earnings management activities could inadvertently increase the effective tax burden, thus reducing the intended level of tax avoidance. Also, Wang and Mao (2021) analyzed an extensive dataset comprising 9428 Chinese firm observations spanning from 2003 to 2015. Their evaluation was based on real earnings management activities, following Roychowdhury’s (2006) model (2006). Interestingly, their findings revealed an inverse relationship, indicating that managers extensively involved in real earnings management activities exhibited fewer tax avoidance behaviors. Similarly, Delgado et al. (2023) found from data from Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Spain during the period of 2006–2015 that earnings management was associated with lower levels of tax avoidance—implying higher ETRs. This counterintuitive result suggests that the nature of earnings management—accrual versus real earnings—could significantly affect its association with tax avoidance.

Although empirical findings exhibit some variations, the majority support agency theory’s predictions: managers’ earnings management activities frequently stem from incentives to minimize corporate tax obligations, thereby promoting tax avoidance. Agency theory explicitly underscores this by highlighting the inherent conflict between managerial self-interest and shareholder interests, providing a clear rationale for why managers might engage in potentially opportunistic behaviors beneficial to themselves at the shareholders’ expense. Based on the above empirical evidence and theoretical underpinning, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1.

Earnings management promotes corporate tax avoidance.

However, gender diversity on corporate boards can reduce agency conflicts between managers and shareholders, thereby lowering earnings management and tax avoidance through governance effectiveness (Amin et al., 2021). For example, Richardson et al. (2016a) conducted an influential study on 205 of Australia’s largest market capitalization firms from 2006 to 2010. They measured tax avoidance through an indicator based on firms’ involvement in tax disputes with the Australian Tax Office (ATO), which is specifically linked to aggressive tax positions. Their findings confirmed that boards with more female directors were significantly associated with lower levels of corporate tax avoidance. The authors attributed this reduction to women’s monitoring capabilities, arguing that female directors effectively oversee managerial activities related to tax strategies. Thus, they concluded that increased female representation substantially improves board effectiveness in supervising management behaviors, advocating the strategic benefit of gender-diverse boards in mitigating tax avoidance. This is also consistent with the study of Hoseini et al. (2019) on the Tehran Stock Exchange from 2012 to 2016, which investigated the direct impact of female presence on boards on corporate tax avoidance. Their results strongly support the view that female directors enhance corporate governance effectiveness, reflected in notably lower tax avoidance levels compared to firms lacking female board representation. Jarboui et al. (2020) also showed that the tax avoidance of corporations decreases when the number of women on the board increases. In their arguments, female directors actively deter managers’ opportunistic and self-serving behaviors, including unethical tax avoidance practices, ultimately safeguarding shareholder interests and supporting sustainable long-term corporate operations. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2022) recently demonstrated a negative correlation between board gender diversity and tax avoidance practices by analyzing listed firms on the Pakistan stock exchange from 2013 to 2017. Consistent with previous findings, the study firmly suggests that improving gender diversity enhances the board’s capability to oversee managerial actions effectively, limiting the occurrence of unethical tax-related decisions. Suleiman (2020) argued that the role of women, the proportion of female directors, and the presence of women on boards have a significant positive impact on the tax avoidance of firms on the Nigerian stock exchange, reflecting the conservatism of women in firms where management compensation is tied to performance. The studies of Oyenike et al. (2016) and Hossain et al. (2024) showed an insignificant association between female directors and tax avoidance.

Therefore, the evidence provided by previous empirical studies favors gender diversity’s role in significantly improving corporate governance practices. Female board directors consistently demonstrate stronger ethical judgment, more effective monitoring capabilities, and greater risk aversion, effectively reducing agency conflicts and discouraging managers from engaging in tax avoidance. Given the strong empirical support from previous research, this study hypothesizes the following:

H2.

Female involvement on the board of directors reduces corporate tax avoidance.

Further debating the role of female directors in earnings management and tax avoidance, agency and political cost theories explain that female board representation significantly affects incentives by mitigating both agency conflicts (Amin et al., 2021) and political costs (DeBoskey et al., 2018). Thus, female directors act as important moderators, potentially weakening the relationship between managerial earnings management and corporate tax avoidance.

Although studies directly examining gender diversity’s moderating role specifically in the earnings management-tax avoidance relationship are limited, several related investigations provide valuable insights. Riguen et al. (2020), for instance, studied 270 UK enterprises from 2005 to 2017, assessing how gender-diverse boards influence the link between audit quality and tax avoidance behaviors. Their results indicated that female board members substantially moderated this relationship by emphasizing higher audit quality demands, reducing managerial opportunism, and subsequently lowering corporate tax avoidance. Giannarou and Tzeremes (2025) also examined data from 191 publicly traded hospitality and tourism firms between 2011 and 2022. They confirmed the moderating role of female directors in the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and tax avoidance. Their study, underpinned by agency, stakeholder, and resource dependence theories, highlighted that female board members’ inherent risk aversion and conservative decision-making significantly enhanced board monitoring effectiveness and decision-making quality. Further empirical evidence from Hossain et al. (2024) strengthened this perspective by considering 62 listed companies in Bangladesh from 2009 to 2020. Their analysis focused on how board gender diversity moderated the influence of firm characteristics such as profitability and firm size on tax avoidance. According to their results, female directors effectively controlled managerial behavior and limited tax avoidance strategies by introducing more stringent oversight, ethical governance practices, and enhanced risk management. According to T. K. Tran et al. (2023), firms typically engage in aggressive tax planning when facing heightened risks. For instance, managers primarily resort to earnings management tactics to enhance the firm’s financial appearance, thus managing perceived short-term risks. Hence, it is reasonable to anticipate that boards with female members, characterized by higher ethical standards, greater conservatism, and stronger risk aversion, will effectively moderate the impact of earnings management on corporate tax avoidance. Such boards inherently constrain managers’ ability to manipulate earnings to achieve aggressive tax objectives, leading to more responsible and sustainable corporate behavior.

In summary, the empirical evidence and theoretical foundations clearly illustrate that female directors, through superior ethical practices, stronger monitoring capabilities, and strategic risk management, help to reduce managerial opportunism in earnings management, ultimately limiting tax avoidance practices. Consequently, the following hypothesis emerges:

H3.

Female involvement on the board of directors reduces the impact of earnings management on corporate tax avoidance.

3. Background, Econometric Model, Data, and Method

This section discusses the Vietnamese context, the relevant measurement and empirical models of income management and tax evasion, and the relevant data and estimation methods.

3.1. Vietnamese Background

According to Q. Nguyen et al. (2024), investigating earnings management and tax avoidance in Vietnam is critical due to the significant corporate governance failures revealed by several high-profile scandals, e.g., the sudden bankruptcies, earnings inflation cases, and downward manipulations by some listed companies on the Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange (HOSE) or the Hanoi Stock Exchange (HNX). These scandals highlighted serious weaknesses in Vietnam’s corporate governance structure, notably the higher concentration of managerial power at the top, conflicts of interest on boards, and ineffective supervisory mechanisms (T. K. Tran et al., 2023; Q. Nguyen et al., 2024). Given the unique institutional characteristics of its emerging economy, such as weak supervision, lack of knowledge of corporate governance and heavy reliance on accounting data that is not reliable enough for decision-making (Truong, 2022; Binh et al., 2022), Vietnam is a suitable representation of developing countries in this paper. In addition, female representation on the boards of listed companies in Vietnam remains a significant challenge despite some progress in terms of women’s rights and gender equality on the part of employers (Anh & Khuong, 2022). In societies characterized by patriarchal cultures, the influence of female leaders may be limited by structural and cultural factors. While women may hold board positions, they often face accusations of “tokenism”—that is, only nominal representation—and have few opportunities to actually participate in key decision-making processes (Nakajima et al., 2025). In addition, traditional social norms often assign management and power roles to men, thereby reducing the actual level of influence of female leaders in businesses. These limitations, therefore, provide an excellent opportunity to revisit the female role in reducing unethical practices, including earnings management and tax avoidance, address Vietnam’s specific corporate governance challenges, and contribute to enhancing financial transparency and protecting stakeholder interests in this emerging market. This will also provide a more comprehensive understanding to the public about the image of female leadership in companies in emerging countries.

3.2. Econometric Model

This study developed a research model based on prior studies to examine the relationship between gender diversity, earnings management, and corporate tax avoidance in nonfinancial listed companies in Vietnam. The model builds on the frameworks of tax avoidance—represented by the Effective Tax Rate (ETR)—used in the studies of T. K. Tran et al. (2023), Delgado et al. (2023), and Zingales (2017), with the inclusion of two new explanatory variables: earnings management (Thalita et al., 2022; Anh & Khuong, 2022) and female involvement on the board of directors (Hossain et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2022). The core model is formulated as follows:

Equation (1) is interpreted into the linear Equation (2) with the participation of control variables (CV) representing the characteristics of the enterprise:

where TAXV measures tax avoidance, calculated by the opposite Effective Tax Rate (ETR), including TAXV1 (current tax expense/income before tax) and TAXV2 (total tax expense/income before tax). TAXV1 calculates the current taxes payable immediately, showing the level of tax avoidance in the short term more clearly, while TAXV2 reveals the collective proportion of accounting income payable as taxes, measuring tax avoidance relative to accounting earnings. Hence, a higher TAXV indicates greater tax avoidance in both indices (Habib et al., 2024). EM represents earnings management, evaluated through accrual earnings management (AEM) and real earnings management (REM) (see details in Appendix A), as in previous studies such as those by Cui et al. (2020) and Kim and Yasuda (2021). Meanwhile, FEIB captures female directors on the board of directors, measured by the proportion of female directors on the board. In addition, this study also explains the moderating role of female involvement on the board of directors in the relationship between EM and TAXV as follows:

If the regression coefficient of the interaction variable β4 is statistically significant, it shows that gender diversity on the board of directors plays a moderating role in the relationship between the earnings management and tax avoidance behavior of enterprises. To control specific characteristics of the firm, a set of control variables (CV) was established—financial leverage (DEBT), fixed assets (FIXA), firm size (LNTA), and firm age (FAGE)—and their hypotheses are based on the related previous studies. For example, greater DEBT increases tax shields, encouraging tax avoidance (Badertscher et al., 2013); a larger LNTA may mean the firm has more resources and opportunities for tax planning (Kimea et al., 2023); a higher number of FIXA is associated with greater depreciation, reducing taxable income (Duhoon & Singh, 2023); and older firms (measured by FAGE) may be more experienced in tax planning but also face higher reputational risk, which can discourage tax avoidance (Lanis & Richardson, 2016). Table 1 shows the variable descriptions and their references.

Table 1.

Variable descriptions and references.

3.3. Data

To address the study’s objectives, we collected data from companies listed on Vietnam’s two main exchanges, the Ho Chi Minh City Stock Exchange (HSX) and the Hanoi Stock Exchange (HNX), covering the period from 2010 to 2022. The period of 2010–2022 was characterized by the issuing of the National Strategy on Gender Equality 2011–2020 (Decision 2351/QD-TTg, made by the Prime Minister on 24 December 2012), the Law on Independent Audit (No. 67/2011/QH12, issued on 29 March 2011), and the Accounting Law (No. 88/2015/QH13, issued on 20 November 2015), which emphasized transparency, accountability, and alignment with international standards. These national changes provided unique frameworks for observing potential shifts in board composition and their implications for corporate behavior as well as gender equality initiatives.

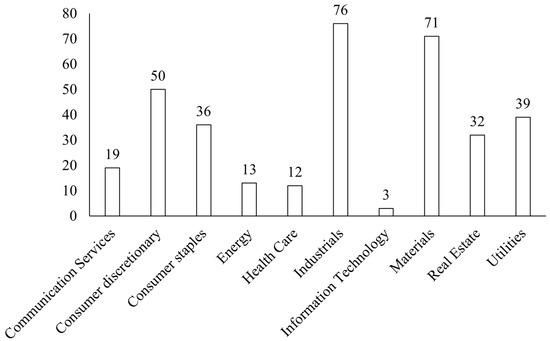

Following the method of previous studies, firms in the financial sector, including banks, financial institutions, securities companies, and insurance firms, were excluded to maintain consistency with the study’s focus. This study also excluded companies that failed to fully disclose information during the study period or were delisted before 2022 to ensure data completeness. This study further excluded firms with an ETR value greater than 1 or with negative values (Habib et al., 2024; Delgado et al., 2023). After applying these criteria, the final sample consisted of a panel of 351 nonfinancial listed companies, totaling 3685 observations. Details on the sample selection are provided in Figure 2, illustrating the number of firms and observations by year over the period of 2010–2022 by different industries and showing a diverse distribution and a sample size large enough to ensure representativeness.

Figure 2.

Number of listed companies in the Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange (HOSE) or the Hanoi Stock Exchange (HNX) by industry.

3.4. Method

The regression method chosen when analyzing the tax avoidance behavior of enterprises is usually the classical/panel Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method. However, recent studies analyzing this topic tended to address the potential endogeneity problem in the research model of tax avoidance behavior. Some authors argued that tax avoidance behavior may have a causal impact on firm characteristics, e.g., firm size and financial leverage (Hlel, 2024; Hossain et al., 2024), and, hence, causality with the error term. Moreover, this endogeneity problem has also been reflected by the presence of a lagged variable of the dependent variable (tax avoidance behavior) (Sani et al., 2024; T. K. Tran et al., 2023; Khuong et al., 2019), which is understood as part of the dynamic nature of the data. A typical dynamic panel model is as follows:

where is a dependent variable for unit i at time t, is a lagged dependent variable (which introduces the dynamic variable), is a vector of explanatory variables, is unobserved individual-specific effects (e.g., firm characteristics), and is an idiosyncratic error term. In dynamic model regression, is correlated with , and, hence, with the error term. This problem violates the standard assumptions of the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method, and panel regressions based on the OLS method, such as Fixed-Effect Models (FEMs) and Random-Effect Models (REMs), leading to biased and inconsistent estimators (Roodman, 2009).

The GMM approach, introduced by Arellano and Bond (1991) and Arellano and Bover (1995), solves endogeneity by using internal instruments, i.e., variables from within the dataset that are correlated with endogenous regressors but not with the error term (e.g., or as instruments for or ). The GMM uses moment conditions (expected value relationships) to exploit these instruments and provide consistent estimates. Hence, the assumptions of the GMM are as follows:

- No second-order serial correlation in errors (AR(2) test).

- Validity of instruments (tested with Sargan/Hansen tests).

- Strict exogeneity of instruments used.

For dynamic panels, Arellano and Bond (1991) introduced the Difference-GMM. It uses first differences to eliminate unobserved individual-specific effects as follows: . Instruments for could be , , etc. However, weak instruments occur when variables are persistent, making weakly correlated with in short panels (a few time periods). Then, Arellano and Bover (1995) and Blundell and Bond (1998) enhanced the Difference-GMM by combining the differenced and level equations to make a System-GMM estimation. It uses the following:

- Lagged levels are instruments for first differences (like the Difference-GMM).

- The second equation (level equation): , using lagged differences as instruments for levels (e.g., as an instrument for ).

Hence, the System-GMM has more advantages than the Difference-GMM, especially when variables are persistent. It also gives greater efficiency, lowers finite sample bias (particularly in short panels), and effectively handles endogenous and predetermined variables (Blundell et al., 2001). Recent studies, such as those by Hlel (2024), Sani et al. (2024), T. K. Tran et al. (2023), and Khuong et al. (2019), and many other studies employed these techniques to explore similar dynamics in tax avoidance, reinforcing the appropriateness and reliability of this method.

4. Findings and Discussions

This section focuses on interpreting the estimation results and discussing the results with related theories and previous research.

4.1. Findings

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the dependent, independent, and control variables used in the research model. The ETR variable reflects the proportion of tax paid by enterprises relative to their pre-tax income, with a mean value of 0.1912 and a standard deviation of 0.0839. This suggests that, on average, firms in the sample pay approximately 19.12% of their pre-tax income in taxes. In terms of accrual-based earnings management, the proxies AEM1, AEM2, and AEM3 each report a mean value of 0.0822, indicating that the enterprises manage earnings through accruals equivalent to about 8.22% of their total assets. Similarly, real earnings management, measured using EM1, EM2, and EM3, shows average values of 0.0974, 0.0627, and 0.1094, respectively. These figures imply that managers engage in earnings management of approximately 9.74%, 6.27%, and 10.94% of the total assets through operational activities such as manipulating cash flows, production costs, and discretionary expenditures. Finally, FE, which represents gender diversity on the board of directors, has a mean of 0.1534 and a standard deviation of 0.1663. This indicates that female directors constitute roughly 15.34% of board members, a relatively low proportion. For instance, based on the typical board size of 11 members regulated by Vietnam’s Enterprise Law, this equates to only one or two female directors per board.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3 presents the correlation matrix of the variables used in the research model. The results indicate that the proxies for earnings management exhibit a negative univariate linear correlation with the tax avoidance variable, significant at the 10% level. Furthermore, the correlations among the independent variables are all below 0.8, suggesting a relatively low degree of association and reducing initial concerns about multicollinearity.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix.

In addition, the results of autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity tests are presented in Table 4. As shown, the Wooldridge test for autocorrelation rejects the null hypothesis of no serial correlation, with a p-value of 0.0000, indicating the presence of autocorrelation in the error terms. Similarly, the results of the Modified Wald test for groupwise heteroskedasticity showed that all p-values are below the 10% significance level. This led to the rejection of the null hypothesis, confirming that heteroskedasticity is also present. These findings suggest that the model’s residuals violate classical assumptions, necessitating robust estimation techniques.

Table 4.

Diagnostic tests.

Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 present the relationship between earnings management (EM) and corporate tax avoidance (TAXV) under FEM and REM regressions. Based on their results, it can be seen that there is an inconsistency in the direction of the impact of earnings management variables on corporate tax avoidance. Specifically, when using models with AEM variables, the impact of earnings management on tax avoidance is often negative and statistically significant, indicating that accounting earnings management can reduce the level of tax avoidance. However, when using EM variables, the results are unstable: some models show a positive impact, and some are not statistically significant, reflecting the ambiguity in the relationship. This inconsistency may originate from endogeneity as well as from the phenomenon of heteroscedasticity, which cannot be resolved by FEM and REM estimation, reducing the reliability of the estimates. These are common limitations in panel data analysis and need to be controlled in the next steps of the GMM analysis.

Table 5.

Earnings management, female leadership, and firm tax avoidance (TAXAV1)—FEM regression.

Table 6.

Earnings management, female leadership, and firm tax avoidance (TAXAV1)—REM regression.

Table 7.

Earnings management, female leadership, and firm tax avoidance (TAXAV2)—FEM regression.

Table 8.

Earnings management, female leadership, and firm tax avoidance (TAXAV2)—REM regression.

The tables below present the relationship between earnings management (EM) and corporate tax avoidance (TAXV) and assess the role of female board participation (FEIB) as a control variable (Table 9 and Table 10) and a moderator variable, EM × FEIB (Table 11 and Table 12). The GMM regression results presented in these tables show that the model’s suitability and reliability have been verified through important diagnostic tests. Specifically, the AR(2) tests indicate that all p-values exceed the 0.1 significance threshold, indicating that there is no second-order serial correlation in error terms, a necessary condition to ensure the validity of the GMM estimate (Arellano & Bover, 1995; Blundell & Bond, 1998). In addition, the Hansen test for the validity of the instrumental variables also gives positive results, with most p-values ranging from 0.1 to 0.4, following the suggestions of Roodman (2009). This shows that the instruments used in the model are appropriate and show no signs of misuse. Furthermore, the difference-in-Hansen test continues to confirm the exogeneity of the instrument subsets with high p-values (p-value ≥ 0.5), confirming that they are exogenous and appropriate for the system estimations. These results collectively support the robustness of the instrument set and justify the use of the System-GMM estimator over the Difference-GMM alternative. After using the two-step System-GMM estimation, the results show consistency in the direction of the impact of earnings management and the control variables on corporate tax avoidance.

Table 9.

Earnings management, female leadership, and firm tax avoidance (TAXAV1)—GMM regression.

Table 10.

Earnings management, female leadership, and firm tax avoidance (TAXAV2)—GMM regression.

Table 11.

Earnings management, the interaction of female leaders, and firm tax avoidance (TAXAV1)—GMM regression.

Table 12.

Earnings management, the interaction of female leaders, and firm tax avoidance (TAXAV2)—GMM regression.

In the FEM/REM estimations (Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8), the effects of AEM and REM on tax avoidance (TAXV1 and TAXV2) are inconsistent and mostly statistically insignificant, or even slightly negative. However, the results in Table 9 and Table 10 show that all six proxies of earnings management (including the three proxies of earnings management through accruals (AEM1, AEM2, and AEM3) and the three proxies of real earnings management (REM1, REM2, and REM3)) have a positive and statistically significant effect at the 1% level on TAXV1 and TAXV2. These results suggest that when dynamic and endogenous factors are not well controlled, as in FEM/REM, the true relationship between earnings management and tax avoidance may be misjudged or obscured. In Table 9, the coefficient of AEM1 is 0.0258 (t = 3.98), while the coefficient of REM1 is 0.0364 (t = 6.80), indicating that firms that practice earnings management have a greater tendency to avoid taxes. For the FEIB variable, the results also show a clear differentiation between the two methods, with most of them being statistically insignificant in the FEM/REM estimations. In the GMM estimations, the FEIB variable exhibits a highly significant negative coefficient in all models, with values ranging from −0.0315 to −0.0943 (e.g., 0.0336 in AEM1, −0.0345 in REM1), indicating that the presence of women on the board of directors is negatively related to tax avoidance. In other words, a higher proportion of women on the management team is associated with fewer firm tax avoidance behaviors.

Table 10 extends the analysis with TAXAV2 as the dependent variable, an alternative measure of tax avoidance. The results maintain a similar trend, with AEM coefficients ranging from 0.0397 (AEM1) to 0.0630 (AEM3) and REM coefficients ranging from 0.0089 (REM3) to 0.0344 (REM2). Notably, AEM is often noted as a popular method of earnings management that is more influential than REM (Richardson et al., 2016b). However, this study shows that the two indices, REM1 (based on discretionary cash flows from operations) and REM2 (based on discretionary production costs), have a stronger or equivalent impact on tax avoidance behavior than the AEM indices. Moreover, in the models using AEM, the EM coefficient is higher than that of TAXAV1, reflecting that accrual accounting has a stronger relationship with tax avoidance in the short term. Similarly, FEIB continues to have negative coefficients ranging from −0.0244 to −0.0764 and is significant at the 1% level, but the absolute values of the coefficients are lower than in Table 9. All of these results will be discussed in detail in Section 4.2.

In Table 11 and Table 12, when the interaction variable between earnings management and the proportion of women on the board of directors (EM × FEIB) is included, the results continue to confirm the positive relationship between EM and TAXV1 as well as TAXV2. In Table 11, all coefficients of the interaction variable are negative and statistically significant at the 1% level, ranging from −0.1625 (REM2) to −0.6002 (AEM1). At the same time, the coefficient of EM increases significantly compared to that in Table 9 (e.g., AEM1 increases from 0.0258 to 0.1095), reflecting that, in the absence of female leadership, the impact of earnings management on tax avoidance becomes more pronounced. In Table 12, the coefficient of the interaction variable EM × FEIB continues to be statistically significant at the 1% level and ranges from −0.2629 (REM1) to −0.8552 (AEM1). These results confirm that female leadership also weakens the relationship between earnings management and tax avoidance. The coefficient of EM in the interaction model continues to increase, notably reaching values of 0.1771 (AEM1) and 0.1114 (REM3), reinforcing the argument that earnings management has a stronger impact on tax avoidance in the absence of women on the board of directors. In both tables, the individual effect of FEIB becomes unstable and is insignificant in some models, emphasizing the significance of the moderating role of the interaction variable. Indeed, the individual coefficient of FEIB in these models reflects the impact of female leadership on tax avoidance when the FEIB x EM interaction is zero, a rare case in practice. Therefore, the real impact of female leadership is only evident when firms engage in earnings management, which is reflected by the negative and highly significant coefficient of the interaction variable. These results suggest that female participation not only directly reduces the level of tax avoidance but also weakens the relationship between earnings management and tax avoidance.

In addition, the control variables DEBT and LNTA have positive effects, while FEIB, FIXA, and FAGE consistently have significant negative effects on tax avoidance behavior, as shown in Table 9, Table 10, Table 11 and Table 12. DEBT (the financial leverage ratio) has a positive coefficient and is statistically significant at the 1% level in all models (e.g., DEBT (AEM1 and AEM3) is 0.0200 in Table 10 and 0.0421 (AEM2) in Table 11, while DEBT (REM1) is 0.0123 in Table 10 and 0.0539 (REM2) in Table 9), suggesting that firms with high debt ratios tend to avoid taxes more, possibly because the pressure from debt obligations motivates tax optimization behavior. Meanwhile, FIXA (the fixed asset ratio) has a negative coefficient in TAXV1 models and is statistically significant in many cases (e.g., FIXA (AEM1) is −0.0153 in Table 9 and −0.0099 (AEM3) in Table 11) but is mostly not statistically significant in the models with TAXAV2, except for when it has the value of −0.0093 (t = −2.79) in the REM2 model. This result suggests that large numbers of fixed assets may reduce the possibility of adopting flexible tax avoidance strategies due to their rigidity and transparency. LNTA (the logarithm of assets) has a positive and statistically significant coefficient ranging from 10% to 1% in the four tables. For example, LNTA (AEM1) is 0.0012 (t = 1.77) in Table 9 and increases to 0.0038 (t = 3.09) in Table 11 (AEM3), and LNTA in REM3 is 0.0012 (t = 2.48) in Table 10 and increases to 0.0046 (t = 3.76) in Table 12, suggesting that larger firms tend to have higher levels of tax avoidance, possibly because they have the resources and capabilities to implement more sophisticated tax strategies. FAGE (firm age) is always negative and highly statistically significant in all models. For example, FAGE in AEM1 is −0.0052 (t = −4.59) in Table 11 and –0.0026 (t = −4.59) in Table 12. Similarly, FAGE (REM2) is −0.0156 (t = −13.67) in Table 11, while FAGE (REM1) is –0.0051 (t = −4.33) in Table 11. These results suggest that older firms are less likely to avoid taxes because they have established a reputation and tend to better comply with the law.

4.2. Discussions

The empirical findings provide clear support for all three proposed hypotheses, interpreted through the frameworks of agency theory, political cost theory, and resource dependence theory. First, the regression results from Table 9 and Table 10 confirm a statistically significant and positive association between all proxies of earnings management (both accrual-based and real-activity-based) and corporate tax avoidance. This outcome is consistent with the predictions of agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Desai & Dharmapala, 2009), which emphasizes the conflict of interest between managers and shareholders. Managers, incentivized by performance-linked compensation, may engage in earnings management to reduce taxable income and enhance reported profitability (Amidu et al., 2019; Kovermann & Velte, 2019). This behavior reflects managerial opportunism aimed at maximizing personal benefits. Previous empirical studies support this view, including those by Hlel (2024), Thalita et al. (2022), and Amidu et al. (2019), all of which found that earnings management is commonly used to support tax minimization strategies. These findings are also consistent with political cost theory (Watts & Zimmerman, 1983), which posits that large firms may adopt conservative reporting practices to reduce public scrutiny and tax burdens. The consistent and significant results across models confirm Hypothesis 1 and reinforce the argument that earnings management is closely linked to tax avoidance behavior.

However, this study shows that indicators such as REM1 (based on discretionary cash flows from operations) and REM2 (based on discretionary production costs) have a stronger impact on tax avoidance than the AEM indicators in some models. This is because the institutional environment and accounting systems in developing countries are still in the process of being perfected, and enterprises tend to prioritize forms of earnings management that are difficult to detect, typically REM—disguised as normal business decisions (e.g., operating cash flows or production cash flows)—which is harder to trace than AEM, which leaves clear traces in accounting items such as provisions, depreciation, or revenue recognition (Almaharmeh et al., 2024). Moreover, in the context of a tax system that does not have a strict separation between accounting profits and real taxable profits, the manipulation of costs and cash flows through real operations easily leads to higher tax avoidance efficiency. Indeed, AEM, with its clear reporting characteristics, is more easily detected by auditors or regulators, while REM is a less risky strategy for concealing tax avoidance through real earnings management (Elmawazini et al., 2024). This result reflects the preferred difference in accounting practices that help businesses achieve their profit and tax objectives in the context of a developing economy.

Second, the findings support Hypothesis 2 by demonstrating a significant negative relationship between female board representation and corporate tax avoidance (Table 9 and Table 10). These findings reflect the governance-enhancing role of women in the boardroom, as suggested by agency theory. Female directors contribute to more effective monitoring, promote ethical standards, and reduce managerial discretion in tax-related decisions (Kwamboka et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2022; Amin et al., 2021). These results align with earlier studies such as those by Richardson et al. (2016a), Hoseini et al. (2019), and Zhang et al. (2022) which found that boards with higher levels of female participation are associated with lower levels of tax avoidance. This finding is further supported by resource dependence theory (Hillman & Dalziel, 2003), which emphasizes that gender-diverse boards enhance a firm’s legitimacy and stakeholder trust. Aggressive tax practices can undermine external relationships and public reputation, whereas the presence of women in leadership helps promote transparency and compliance. Thus, female directors play a preventative role against high-risk or unethical tax strategies, contributing to more sustainable governance outcomes.

Third, the most significant theoretical contribution of this study lies in the confirmation of Hypothesis 3, where the interaction term (EM × FEIB) across all models in Table 11 and Table 12 exhibits a strong and statistically significant negative effect. This finding implies that the presence of women on corporate boards mitigates the extent to which earnings management contributes to tax avoidance. In other words, in firms without female directors, the practice of earnings management, whether through accounting adjustment (AEM) or real operation (REM), is associated with an increased tendency to engage in tax avoidance. However, when firms have female directors, this association becomes weaker or even reverses. These results align with the combined predictions of agency theory and political cost theory. Female directors—through their enhanced ethical awareness, risk aversion, and monitoring effectiveness—limit managers’ ability to exploit earnings management as a vehicle for tax avoidance (Srinidhi et al., 2011; Bart & McQueen, 2013). These results echo prior findings from Riguen et al. (2020) and Giannarou and Tzeremes (2025), which demonstrated that gender-diverse boards are more effective in supervising complex managerial decisions, particularly in ethically sensitive areas such as tax and auditing. Furthermore, this moderating role highlights the governance function of female directors. While earnings management alone increases tax avoidance, the presence of women on the board suppresses direct tax aggressiveness and also disrupts the transmission mechanism from earnings management to tax behavior. This dual effect of direct and moderating influence underscores the strategic importance of board gender diversity in constraining managerial opportunism and maintaining responsible corporate conduct.

Hence, the consistency of the findings in this study, especially in the context of an emerging economy like Vietnam, reinforces the importance of cultural and institutional factors in shaping the effectiveness of gender diversity. This study contributes to the literature by providing comprehensive evidence that not only supports the individual impacts of earnings management and gender diversity on tax avoidance but also sheds light on the interplay between these mechanisms, a dimension that has been underexplored in previous research.

5. Conclusions

This study was motivated by the growing concern over earnings management and tax avoidance practices in emerging markets, where corporate governance systems are often weak, and gender diversity in leadership remains limited. With its history of corporate scandals and underdeveloped regulatory enforcement, Vietnam presents an ideal setting for exploring how internal governance mechanisms—specifically board gender diversity—shape financial behavior. Building on agency, political cost, and resource dependence theories, this study sought to clarify the complex relationships between earnings management, tax avoidance, and female board participation. Using panel data from 351 nonfinancial listed companies in Vietnam between 2010 and 2022 and applying the System-GMM to address endogeneity concerns, this study produced several key findings: First, the results confirmed that both accrual-based and real earnings management are positively associated with corporate tax avoidance, aligning with theoretical expectations of managerial opportunism. Second, the study found a significant negative relationship between female board representation and tax avoidance, reinforcing the view that women contribute to stronger board oversight and ethical governance. Third, and most notably, the findings revealed that female directors significantly moderate the relationship between earnings management and tax avoidance, underscoring the important governance role of women in weakening the pathway through which managers exploit earnings management to reduce tax liabilities.

The findings support initiatives that promote internal control systems and gender diversity on corporate boards to enhance transparency, accountability, and financial integrity. The significant positive link between earnings management and tax avoidance underscores the need for tighter oversight of firms’ financial reporting practices. Auditors, internal control systems, and audit committees should be more vigilant in reviewing accrual-based and real earnings management techniques, particularly when tax outcomes deviate from economic performance. Also, tax authorities should develop risk-based audit models that incorporate earnings management indicators such as abnormal accruals or production costs, which are early warning signals of potential tax avoidance. Regulators and policymakers should consider implementing mandatory or voluntary gender quotas, board diversity disclosure requirements, or targeted leadership development programs for women. For corporate decision-makers, the study highlights the strategic value of including women in leadership roles—not only as a matter of equity but as a governance mechanism that can curb aggressive financial practices. Moreover, gender diversity, as a component of ESG scores, may signal ethical corporate behavior and reduce financial manipulation risk. Institutional investors and asset managers can leverage this information to make more informed capital allocation decisions, encouraging firms to adopt long-term, sustainable strategies over short-term tax arbitrage.

This study also supports SDG 16 and SDG 5 by demonstrating how gender-inclusive governance practices can reduce harmful financial manipulation and promote ethical behavior. It also strengthens women’s roles in decision-making throughout economic life. Encouraging such practices contributes to stronger institutions and more equitable and resilient economic systems. However, this study has certain limitations: It focuses solely on 351 listed firms in Vietnam during 2010–2022, limiting the generalizability of the results to other institutional and timing contexts. The scope is also restricted to quantitative metrics of the number of women on the boards of directors without assessing qualitative aspects such as ethical concerns, educational level, the influence of female directors in strategic committees, or their experience and actual power in decision-making. Future research could expand on these findings by exploring cross-country or group-of-countries comparisons, particularly in Southeast Asian or other emerging markets, to examine the institutional and economic factors that condition the effectiveness of female board participation. Further studies could also incorporate qualitative methods and surveying methods to understand how women in leadership influence board dynamics and ethical decision-making processes in practice. Additionally, integrating variables such as economic factors, political connections, board independence, and corporate social responsibility may provide a more varied understanding of how internal and external governance elements interact to shape corporate tax behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T.H.N. and B.D.M.; methodology, T.T.H.N. and G.Q.P.; software, G.Q.P.; validation, D.K.P., T.V.P. and B.D.M.; data curation, G.Q.P.; writing-original draft preparation, B.D.M.; writing-review and editing, D.K.P., T.V.P. and T.T.H.N.; visualization, D.K.P. and T.V.P.; supervision, T.T.H.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The below section will describe the measurements of earnings management, and the study uses widely accepted models:

- EM1—Jones (1991) model: this model helps separate normal (non-discretionary) accruals—those expected based on a firm’s normal operations—from abnormal (discretionary) ones, which may indicate management. The model assumes that managers can influence accruals to alter reported earnings, but non-discretionary accruals are often tied to fundamental business factors like operating cash flow, revenue and asset changes. The model formula is as follows:where TARit reflects the difference between net income and operating cash flow of firm i at t time. TASit−1 is the lagged total assets of firm i. SALEit is the revenue of the firm i at t time, while ΔSALEit is the change of revenue, measured by , and PPEit is property, plant, and equipment.

- EM2—Dechow et al. (1995) model: this model improves the original Jones model to better capture earnings management by introducing performance-matched discretionary accruals to improve detection accuracy. The authors proposed adjusting revenue changes by subtracting receivables, helping isolate true earnings management from normal performance-driven accruals. The formula is as follows:where ΔRECit is the change of receivables of firms i, and other variables are detailed in Equation (A1).

- EM3—Kothari et al. (2005) model: their model develops on the Modified Jones model by incorporating return on assets (ROA) into the regression equation, controlling for firm performance within the model itself rather than relying on matching techniques. This adjustment makes the Kothari model more robust and less prone to detecting false positives, particularly for high-performing firms whose accruals may otherwise appear abnormal. The model is formulated as:ROAit is measured by the ratio of net income to assets, and other variables are detailed in Equations (A1) and (A2).

While Kothari et al. (2005) focused on accrual-based earnings management, Roychowdhury (2006) specifically developed a model to detect real earnings management (REM), and later studies applied performance-adjustments similar to Kothari’s approach to REM, hence, have influenced later research, including work on real earnings management. REM is typically carried out via:

- Abnormal cash flows from operations (REM1):where REM1 is estimated by the residuals () from the regressions, presenting the difference between the actual cash flows from operations (CFOit) and estimated CFOit from Equation (A4).

- Abnormal production costs (REM2):where REM2 is estimated by the residuals () from the regressions, presenting the difference between the actual production cost (PRODit) and estimated PRODit from Equation (A5) with PRODit = Cost of goods soldit + Chang in inventoryit.

- Abnormal discretionary expenses (REM3)where REM3 is estimated by the residuals () from the regressions, presenting the difference between the actual discretionary expenses (SG&Ait) and estimated SG&Ait from Equation (A6), with SG&Ait as selling, general and administrative expenses.

References

- Alhossini, M. A., Mansour, Z. A., Elmahdy, S. S., & Hessian, M. (2024). Monitoring female directors and earnings management, does corporate governance matter? Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2396538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaharmeh, M. I., Liu, J., & Iskandrani, M. (2024). Analyst coverage and real earnings management: Does IFRS adoption matter? UK evidence. Heliyon, 10(11), e31890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidu, M., Coffie, W., & Acquah, P. (2019). Transfer pricing, earnings management and tax avoidance of firms in Ghana. Journal of Financial Crime, 26(1), 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A., Ur Rehman, R., Ali, R., & Ntim, C. G. (2021). Does gender diversity on the board reduce agency cost? Evidence from Pakistan. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 37(2), 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, L. H. T., & Khuong, N. V. (2022). Gender diversity and earnings management behaviours in an emerging market: A comparison between regression analysis and FSQCA. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2101243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anita, R., Suseno, G., Abdillah, M. R., & Zakaria, N. B. (2024). How do female directors moderate the effect of family control on firm value and leverage? Evidence from Indonesia. Indian Journal of Corporate Governance, 17(1), 102–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badertscher, B. A., Katz, S. P., & Rego, S. O. (2013). The separation of ownership and control and corporate tax avoidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 56(2–3), 228–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bart, C., & McQueen, G. (2013). Why women make better directors. International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics, 8(1), 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazel-Shoham, O., Lee, S. M., Munjal, S., & Shoham, A. (2024). Board gender diversity, feminine culture, and innovation for environmental sustainability. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 41(2), 293–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, T., Hagen, D. V., & Steffens, C. (2018). Taxes and firm size: Political cost or political power? Journal of Accounting Literature, 42(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binh, V. T. T., Tran, N.-M., & Vu, M.-C. (2022). The effect of organizational culture on the quality of accounting information systems: Evidence from Vietnam. SAGE Open, 12(3), 21582440221121599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R., Bond, S., & Windmeijer, F. (2001). Estimation in dynamic panel data models: Improving on the performance of the standard GMM estimator. In H. Baltagi Badi, B. Fomby Thomas, & R. Carter Hill (Eds.), Nonstationary panels, panel cointegration, and dynamic panels (Vol. 15, pp. 53–91). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Bona-Sánchez, C., Fleitas-Castillo, G. C., Pérez-Alemán, J., & Santana-Martín, D. J. (2024). Gender diversity and audit fees: Insights from a principal-principal agency conflict setting. International Review of Financial Analysis, 96, 103614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, I. C., & Dawson, A. (2018). Women leaders and firm performance in family businesses: An examination of financial and nonfinancial outcomes. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 9(4), 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, Y., & Jaiswall, M. (2023). Economic policy uncertainty and incentive to smooth earnings. International Review of Economics & Finance, 85, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Niu, F., & Zeng, T. (2025). Tax planning and earnings management: Their impact on earnings persistence. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 26(2), 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J., & Park, H. (2022). Tax avoidance, tax risk, and corporate governance: Evidence from Korea. Sustainability, 14(1), 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X., Yao, S., Fang, Z., & Wang, H. (2020). Economic policy uncertainty exposure and earnings management: Evidence from China. Accounting & Finance, 61(3), 3937–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damayanti, T. W., & Supramono, S. (2019). Women in control and tax compliance. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 34(6), 444–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBoskey, D. G., Luo, Y., & Wang, J. (2018). Does board gender diversity affect the transparency of corporate political disclosure? Asian Review of Accounting, 26(4), 444–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechow, P. M., Sloan, R. G., & Sweeney, A. P. (1995). Detecting earnings management. The Accounting Review, 70(2), 193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, F. J., Fernández-Rodríguez, E., García-Fernández, R., Landajo, M., & Martínez-Arias, A. (2023). Tax avoidance and earnings management: A neural network approach for the largest European economies. Financial Innovation, 9(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M. A., & Dharmapala, D. (2009). Corporate tax avoidance and firm value. Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(3), 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhoon, A., & Singh, M. (2023). Corporate tax avoidance: A systematic literature review and future research directions. LBS Journal of Management & Research, 21(2), 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmawazini, K., Galariotis, E., Hossain, A. T., & Rjiba, H. (2024). Federal judge ideology and real earnings management. International Review of Financial Analysis, 92, 103110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrary, M., & Déo, S. (2023). Gender diversity and firm performance: When diversity at middle management and staff levels matter. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(14), 2797–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannarou, L., & Tzeremes, P. (2025). CSR performance and corporate tax avoidance in the hospitality and tourism industry: Do women directors moderate this relationship? International Hospitality Review. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, J., Lee, H. Y., & Lee, J. W. (2013). Majority shareholder ownership and real earnings management: Evidence from Korea. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 24(1), 26–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, M. A., Cherian, J., Hwang, J., Jiang, Y., & Sial, M. S. (2019). The impact of board gender diversity and foreign institutional investors on the corporate social responsibility (csr) engagement of chinese listed companies. Sustainability, 11(2), 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A., Ranasinghe, D., & Perera, A. (2024). Strategic deviation and corporate tax avoidance: A risk management perspective. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(4), 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A. J., & Dalziel, T. (2003). Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlel, K. (2024). Tax avoidance and earnings management: Evidence from French firms. International Journal of Financial Engineering, 23, 2450013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, M., Safari Gerayli, M., & Valiyan, H. (2019). Demographic characteristics of the board of directors’ structure and tax avoidance. International Journal of Social Economics, 46(2), 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. S., Islam, M. Z., Ali, M. S., Safiuddin, M., Ling, C. C., & Fung, C. Y. (2024). The nexus of tax avoidance and firms characteristics—does board gender diversity have a role? Evidence from an emerging economy. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 17(2), 401–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itan, I., Zamri, A., Jaslin, S., & Karjantoro, H. (2024). Corporate governance, tax avoidance and earnings management: Family CEO vs. non-family CEO managed companies in Indonesia. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2312972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarboui, A., Kachouri Ben Saad, M., & Riguen, R. (2020). Tax avoidance: Do board gender diversity and sustainability performance make a difference? Journal of Financial Crime, 27(4), 1389–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial Behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J. J. (1991). Earnings management during import relief investigations. Journal of Accounting Research, 29(2), 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuong, N. V., Anh, L. H. T., & Van, N. T. H. (2022). Firm life cycle and earnings management: The moderating role of state ownership. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2085260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuong, N. V., Ha, N. T. T., Minh, M. T. H., & Thu, P. A. (2019). Does corporate tax avoidance explain cash holdings? The case of Vietnam. Economics & Sociology, 12(2), 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., & Yasuda, Y. (2021). Economic policy uncertainty and earnings management: Evidence from Japan. Journal of Financial Stability, 56, 100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimea, A. J., Mkhize, M., & Maama, H. (2023). Firm-specific determinants of aggressive tax management among east African firms. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 13(3), 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, S. P., Leone, A. J., & Wasley, C. E. (2005). Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(1), 163–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]