4.1. Descriptive Analysis

After the selection process, a brief analysis allowed us to make some general observations.

Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the publications from 2000 to November 2024, including key metrics such as citation rates, publication-to-citation time, and author productivity. Additionally, the table highlights the extent of collaboration within the field. The publications included 183 articles, 49 proceeding papers, 10 review articles, and 5 early access articles, authored by 747 researchers. These publications were associated with 160 scientific journals and conference proceedings.

Only six journals had four or more publications on the topic (Sustainability; Journal of Cleaner Production; International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management; Journal of Business Ethics; and Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal). However, these six journals were responsible for twenty eight percent of our dataset. It is interesting to note that none of the most influent journals were from the accounting field. A significant portion of the research (83%) was collaborative, involving an average of 3.27 co-authors per paper. The average number of citations per paper was 21.91, suggesting a substantial impact of research in this area, and 24.29% of the collaborations were international, highlighting the global nature of this field.

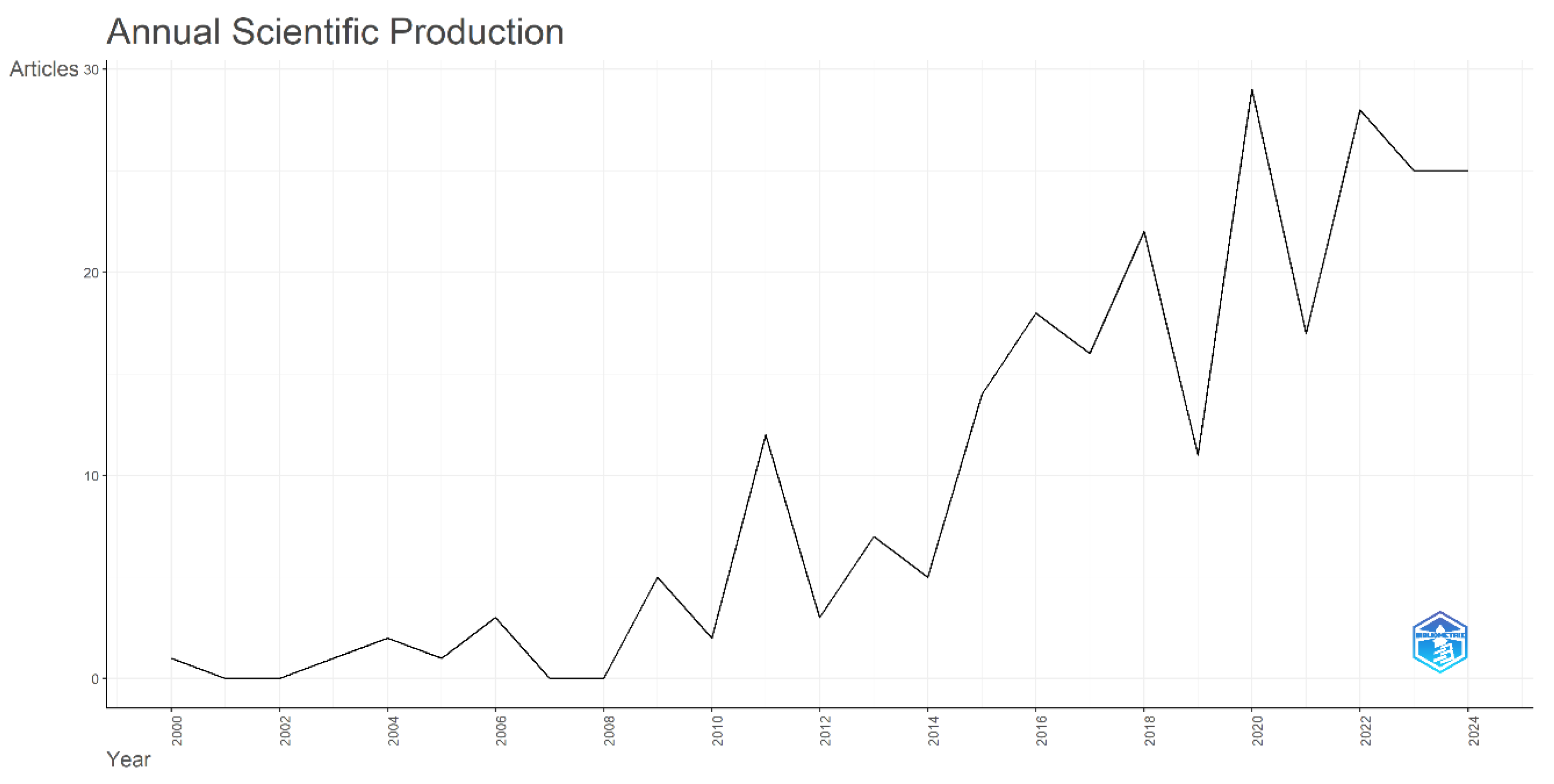

From 2000 to 2010, only 15 documents were published. The first paper identified was published in 2000 in conference proceedings. During this early period, applications of the SBSC were largely conceptual, with few empirical cases. In 2011, the number of publications reached 12, demonstrating a growing interest in the topic. From 2018 onwards, a significant shift was observed: the most fruitful recent years were 2018, 2020, 2022, 2023, and 2024, with annual publications ranging between 22 and 29 (

Figure 2). The annual percentage growth rate was 14.35, reflecting the rising integration of SBSCs into organizational practice. In 2020, applications expanded into healthcare, with case studies from hospitals in Iran (

Asadi Louye et al., 2026), highlighting the role of SBSCs in managing sustainability and patient care simultaneously. The years 2022 and 2023 saw further diversification, including the use of SBSCs in SMEs in Brazil’s manufacturing sector (

Barbosa et al., 2020b), and in logistics and supply chain management in China (

Zhang et al., 2023), often combined with digitalization tools such as IoT and big data analytics. These recent trends illustrate not only the quantitative growth of the field but also a qualitative shift toward sector-specific applications and digital integration.

4.2. Performance Analysis

Table 3 presents the top 20 most successful authors in the field of SBSC, ranked by various metrics, including the h-index, g-index, m-index, and total citations.

Hubbard, G. (

Hubbard, 2009) stands out as the most influential author, with over 438 citations for only one publication in 2009, “Measuring organizational performance: beyond the triple bottom line”, published in

Business Strategy and the Environment. Yet among the top twenty, there are nineteen other authors with more than one hundred citations. Schaltegger, S. follows closely with 336 citations, and Di Vaio, A. and Varriale, L. present 216 citations each. While Hubbard, G. has a higher citation count, it is important to consider the h-index, which measures both productivity and impact. Schaltegger, S. (

Möller & Schaltegger, 2005), with “The sustainability balanced scorecard as a framework for eco-efficiency analysis” published in the

Journal of Industrial Ecology, demonstrated a strong h-index, indicating substantial contributions to the field. For emerging researchers, the m-index is a more suitable metric. Di Vaio, A. and Varriale, L. exhibit promising m-indices, signifying their potential for future impact. The majority of top-contributing authors began their research careers after 2013/2014, highlighting the recent growth and increasing interest in SBSC research.

Table 4 presents the most influential articles based on global citations. This metric reflects the total number of times an article has been cited across various databases, and the number of citations received from highly cited papers serves as a measure of an article’s impact. The paper titled “Measuring Organizational Performance: Beyond the Triple Bottom Line” by

Hubbard (

2009) is the most influential article, with a total of 438 citations, averaging 27.38 citations per year. This paper has become a central reference pillar in BSC research, addressing the challenge of measuring sustainable organizational performance. It proposes a simplified, stakeholder-based SBSC framework, along with an organizational sustainability performance index. This index aims to integrate various sustainability measures into a single, easily understandable metric, making it more accessible to stakeholders.

Hsu et al. (

2011) and

Costa and Menichini (

2013) follow with 140 and 133 citations per year, respectively.

Hsu et al. (

2011), with “Using the FDM and ANP to construct a sustainability balanced scorecard for the semiconductor industry”, adapt the traditional BSC by replacing the financial and customer perspectives with sustainability and stakeholder perspectives. Their proposed framework aims to enhance the sustainable competitiveness of Taiwanese semiconductor companies. “A multidimensional approach for CSR assessment: The importance of the stakeholder perception” by and

Costa and Menichini (

2013) investigates the impact of CSR on stakeholder perception and business performance. By combining Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) indicators and the BSC framework, the authors develop a multi-criterion model to assess CSR performance. The model considers both financial and non-financial dimensions, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of a company’s social behavior from various stakeholder perspectives. The study highlights the importance of effective communication and transparency in CSR initiatives to positively influence stakeholder perceptions and ultimately enhance business outcomes.

Along with

Hubbard (

2009),

Mio et al. (

2022) have one of the highest average citation counts per year at 24.67. The authors investigate the factors that influence SBSC adoption, implementation approaches, and their impact on sustainability control and management, aiming to contribute to the understanding of SBSCs and identify potential future research directions.

However, the most productive author is Schaltegger, S. with five articles since 2005: “The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard as a Framework for Eco-Efficiency Analysis” (

Möller & Schaltegger, 2005), “Managing Sustainability Performance Measurement and Reporting in an Integrated Manner—Sustainability Accounting as the Link Between the Sustainability Balanced Scorecard and Sustainability Reporting” (

Schaltegger et al., 2006), “Management Roles and Sustainability Information. Exploring Corporate Practice” (

Schaltegger et al., 2015), “The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard: A Systematic Review of Architectures” (

Hansen & Schaltegger, 2016), and “Sustainability Balanced Scorecards and their Architectures: Irrelevant or Misunderstood?” (

Hansen & Schaltegger, 2018) (

Table 5).

In

Table 5, we present the twenty most productive authors, aiming to highlight the authors’ contributions both in terms of the total number of articles published and their fractional authorship. Fractional authorship quantifies an individual author’s contribution to a set of papers, considering factors like co-authorship (

Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017). Our analysis revealed that Schaltegger, S. also demonstrated the higher level of individual contribution, with a fractional authorship score of 2.2, indicating his involvement in multiple papers.

Figure 3 visualizes the authors’ productivity and impact over time. The line chart represents the publication timeline of each author, with Schaltegger, S. showing the longest active period from 2005 to 2018. The size of the bubbles indicates the number of documents published in a given year, and the color intensity of the bubbles reflects the total citations received per year, with 2018 being the most productive by author and number of citations: Di Vaio, A. and Varriale, L. with two articles (“Key performance indicators for developing environmentally sustainable and energy efficient ports: evidence from Italy” (

Di Vaio et al., 2018) and “Management innovation for environmental sustainability in seaports: managerial accounting instruments and training for competitive green ports beyond the regulations”) (

Di Vaio & Varriale, 2018) and 25.9 citations per year (

Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017).

These authors are followed by

Barbosa et al. (

2020a,

2020b) with two articles (“Sustainable strategic management (GES): sustainability in small business” and “Sustainable management, balanced scorecard and small business: a systematic review and state of the art”) and 11.4 citations per year and by Alvarez-Perez, C. in 2017 with two articles (“Integration of balanced scorecard (BSC), strategy map, and fuzzy analytic hierarchy process (FAHP) for a sustainability business framework: a case study of a Spanish software factory in the financial sector” and “Integrating analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and balanced scorecard (BSC) framework for sustainable business in a software factory in the financial sector”) and 2.12 citations per year (

Álvarez Pérez et al., 2017a,

2017b).

Authors such as Dincer, H.; Yuksel, S.; Kant, R.; Ali, S.M.; and Cheikhrouhou, N. started publishing in this area more recently and had several new publications in 2024.

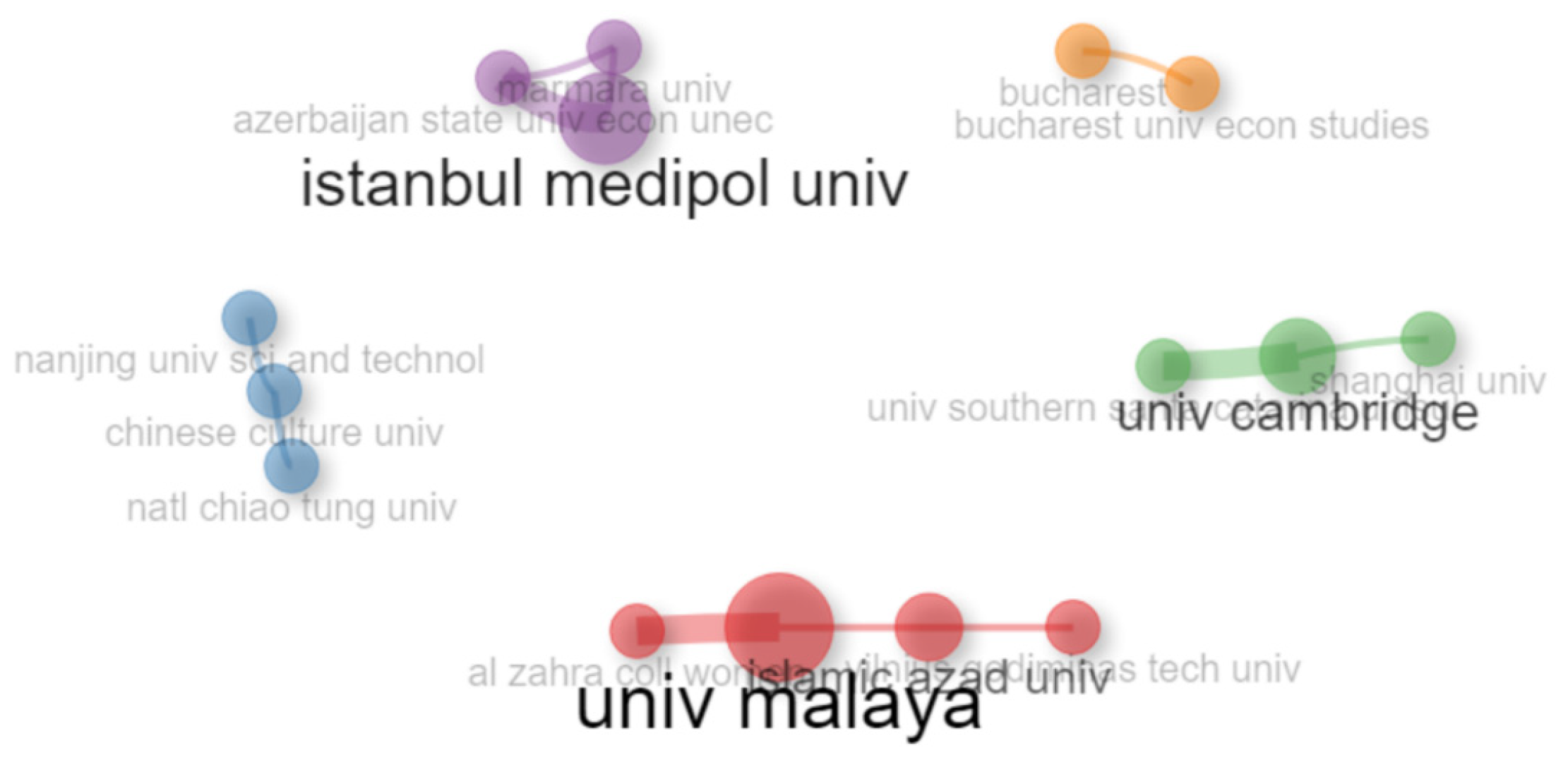

Regarding the author’s affiliations, in

Table 6, the Univ. Naples Parthenope—Italy presents the higher number of articles, followed by Istanbul Medipol Univ.—Turkey and Univ. Malaya—Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. It is interesting to note that these authors come from universities in diverse countries with different levels of development, and it is clear that the concern for sustainability and sustainability reporting is universal.

To gain insights into the collaborative landscape of research in this field, we also analyzed the network of institutional collaborations. By mapping the connections between institutions, we can identify key players and collaboration patterns. This analysis helps us understand how knowledge and resources are shared and how research communities evolve over time.

Figure 4 illustrates the network of institutional collaborations, highlighting the most influential institutions and their interconnections.

Figure 4 visually represents the clustering of research institutions, and the size of each node corresponds to the institution’s research output, with larger nodes indicating higher productivity.

The connections between nodes signify cross-citations between researchers from different institutions, reflecting the extent of international collaboration.

Table 7 presents the institutions with the highest centrality index, highlighting their significant influence within the research network.

The analysis of institutional connections reveals that Asian institutions hold a prominent position in the global research network on SBSC, as indicated by their high centrality index. Additionally, some European institutions play significant roles in international collaborations, highlighting the importance of global scientific cooperation in addressing sustainability reporting.

To understand the current state of research on SBSCs and their future trajectory, it is also crucial to identify the main journals in this field. Our total of 247 articles analyzed were published in 53 journals and conference proceedings.

Table 8 shows the main journals based on the number of publications.

Sustainability ranks first, with 34 articles, followed by

Journal of Cleaner Production with 17 articles. These two journals together published approximately 21% of the total number of articles analyzed in this study.

Only three journals reached five publications on the topic: the International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management; Journal of Business Ethics; and Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal. Collectively, the top ten journals accounted for a 32% of the total number of articles from our dataset. It is interesting to note that none of the most influent journals were specific to the accounting field.

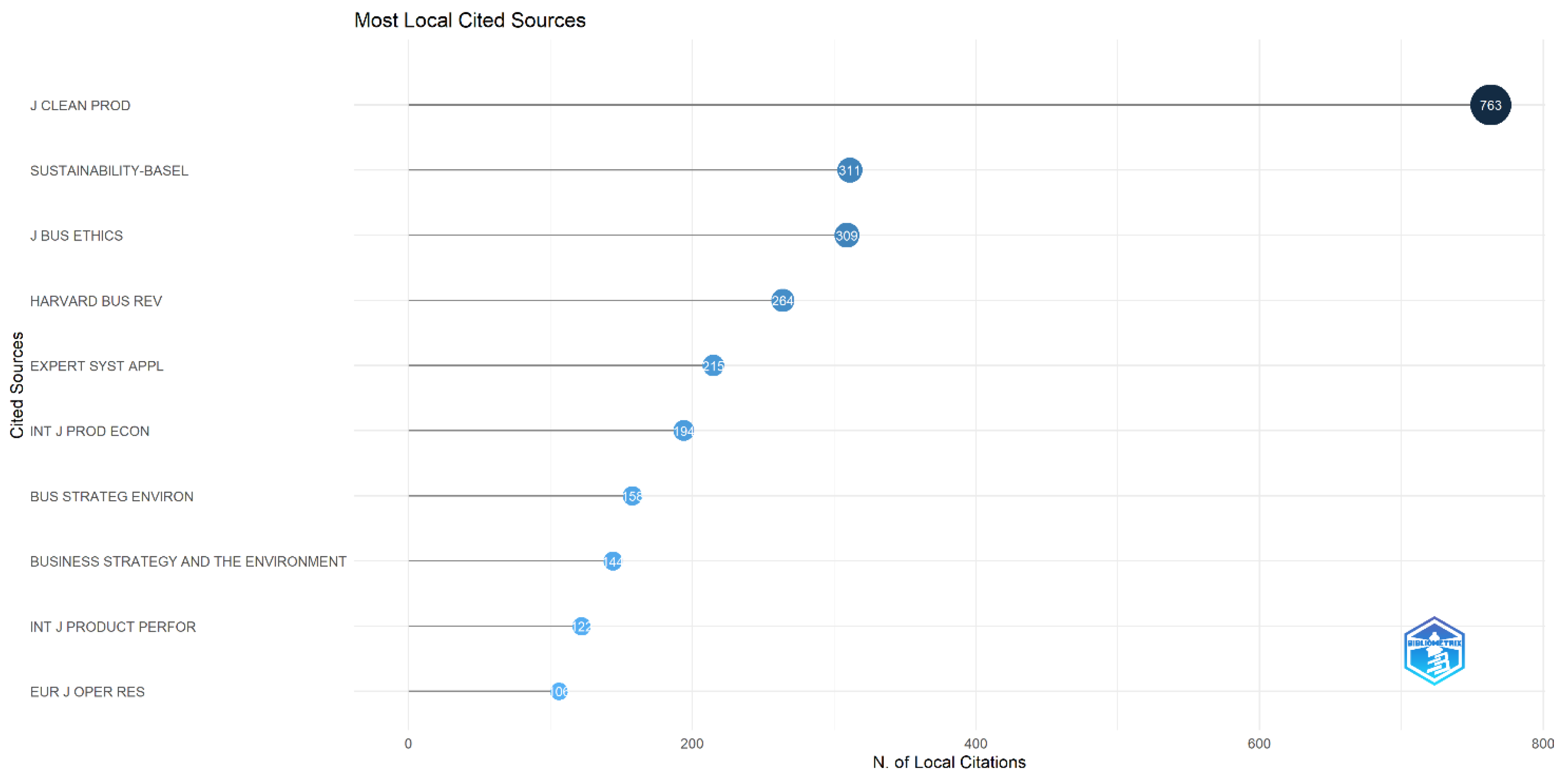

Regarding the most cited sources in the WoS database, we find the

Journal of Cleaner Production, with 763 citations for 17 articles. Next, we find

Sustainability with 311 citations and the

Journal of Business Ethics with 309 citations (

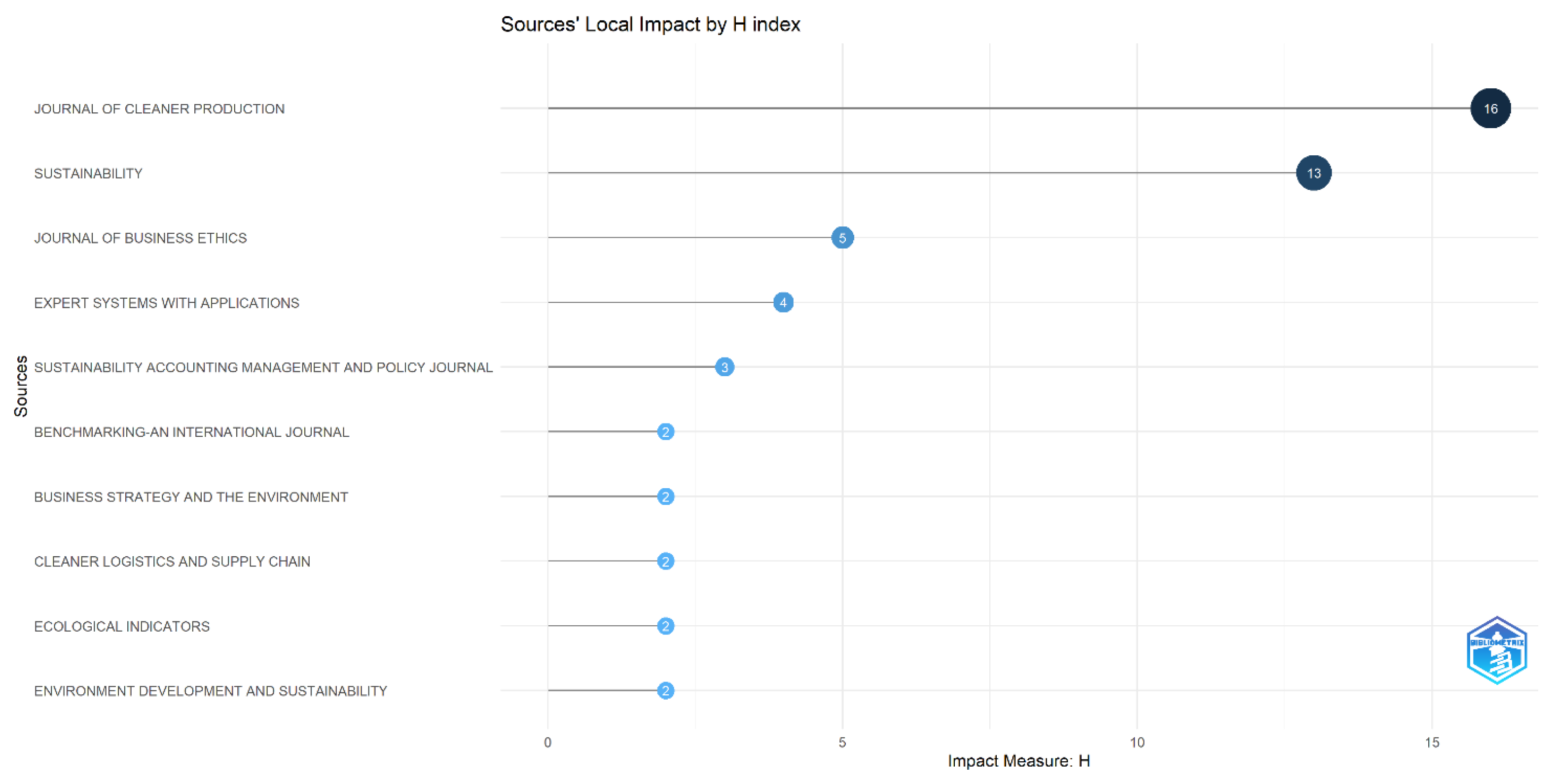

Figure 5). This analysis also allows us to evaluate the sources impact, with the

Journal of Cleaner Production publishing 17 articles, reaching 763 citations and an impact measure of H = 16, while

Sustainability, with twice as many articles, has 311 citations and an impact measure of H = 13 (

Figure 6).

Figure 6 presents the publication sources’ local impact for our final sample of 247 documents collected from the WoS database using a combination of terms, namely, “BSC or Balanced Scorecard” AND “Sustainability”, for the timespan of 2000–2024.

When analyzing the contributions of various countries to scientific publications on SBSCs (sustainable business and social responsibility), it can be seen that the studies originate from a wide range of countries, covering Europe, Asia, Oceania, and South America (

Figure 7). This geographical diversity shows that concern for sustainability and SBSC usage is a global priority, adopted by companies in economies at all levels of development. This widespread involvement underlines the universal recognition of the importance of integrating sustainable practices and social responsibility into business models in different economic contexts.

The analysis of the most productive countries in

Figure 8 reveals that China and Spain lead the ranking with 22 (16 single-country and 6 collaborative) and 20 (17 single-country and 3 collaborative) publications, respectively. Next, we find Germany (15 publications = 13 SCP + 2 MCP), India (14 publications = 13 SCP + 1 MCP), Brazil (15 publications = 8 SCP + 4 MCP), Italy (15 publications = 10 SCP + 2 MCP), and Australia (10 publications = 5 SCP + 5 MCP). Australia presents the one of the highest MCP ratios at 0.5. This global participation also signifies a collective movement toward a more sustainable and responsible future.

4.3. Thematic Evolution and Cluster Analysis

Sustainability balanced scorecard (SBSC) studies have gained increasing academic and practical attention, reflecting organizations’ demand for tools that align financial performance with sustainability objectives (

Agarwal et al., 2022;

Fatima & Elbanna, 2023;

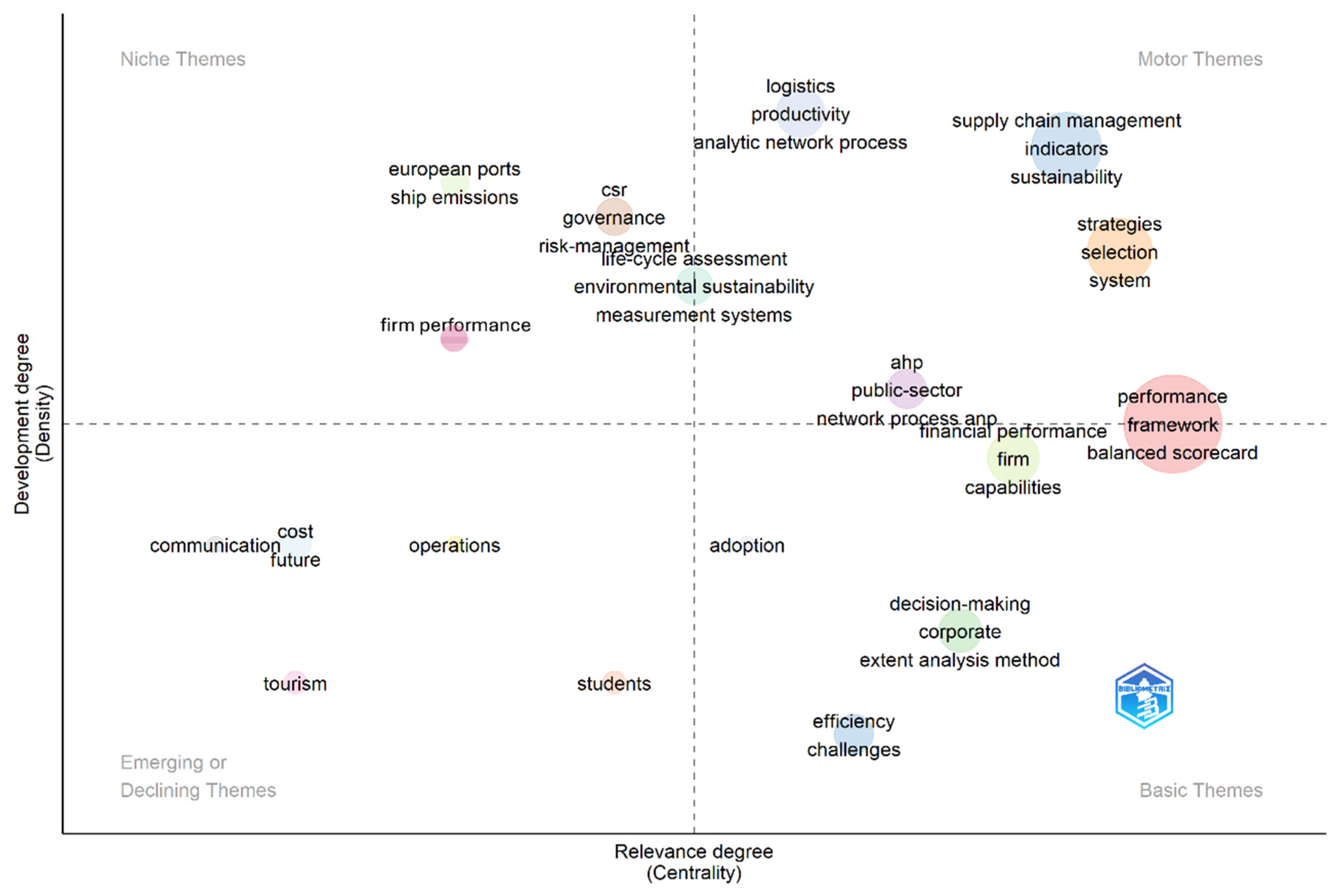

Fernández-González et al., 2023). The strategic diagram presented in

Figure 8 is a valuable tool for understanding the intellectual structure of a research field. It helps to visualize the relationships between different research themes and identify potential areas for future research. The four quadrants represent different thematic areas based on their centrality (relevance degree) and density (development degree), identifying emerging or declining themes, niche themes, basic themes, and motor themes.

In the motor themes quadrant, we find sustainability, performance measurement systems, and balanced scorecard. These themes are well established, highly cited, and central to the field, representing the core research topics that drive the SBSC field forward. Sustainability is central to the field, indicating a strong focus on environmentally and socially responsible practices; performance measurement systems are crucial for evaluating organizational performance, particularly in relation to sustainability; and the balanced scorecard is a widely used framework for strategic performance measurement and is a fundamental tool for integrating sustainability into organizational strategies. Regarding niche themes, the thematic map highlights ship emissions and European ports. This indicates a growing interest in the environmental impact of maritime transportation and the need for sustainable port operations.

The connections between themes highlight the interdisciplinary nature of the field. For instance, the link between “sustainability” and “performance measurement systems” indicates that sustainability is increasingly being integrated into performance measurement frameworks. Based on the thematic map, future research can focus on deepening the integration of sustainability into performance measurement systems, exploring how to effectively incorporate sustainability indicators into existing performance frameworks. Addressing the challenges of implementing sustainability initiatives, exploring the barriers to sustainability implementation and developing strategies to overcome them, and investigating the potential of technologies like AI, IoT, and blockchain to drive sustainable innovation are also future fields of research.

Using co-citation clustering, this study employed CiteSpace software, 6.3.R1 Basic version, to map research clusters by analyzing keyword patterns and tracking their frequency to uncover the main terms prioritized by researchers (

Chen, 2006). This approach identified a network of 288 nodes (representing key terms) and 1180 academic connections, all associated with discussions on the BSC and sustainability. The most significant and frequently cited keywords found in articles are depicted in

Figure 9.

The silhouette score, which ranges from 0 to 1, measures the clarity in defining each cluster’s main themes, with higher scores suggesting greater internal consistency and coherence within clusters (

Issah & Rodrigues, 2021). In this analysis, each cluster received scores close to 1, demonstrating that articles were accurately categorized into distinct thematic groups. Among these, the leading clusters emerged around the terms “ Performance Evaluation”, “Sustainability Balanced Scorecard” and “Small Business”.

Based on the methodology of

Enciso-Alfaro and García-Sánchez (

2023), clusters with fewer than 20 keywords were excluded from the analysis to maintain focus on significant thematic areas. Using the log-likelihood ratio clustering algorithm, the program identified seven prominent clusters. Each cluster’s size reflects the number of articles it contains, which ranges from clusters with 51 articles down to those with 35, corresponding to cluster silhouette scores between 0 and 2 (

Table 9).

Cluster 0—Performance Evaluation

This cluster focuses on integrating “performance evaluation” with sustainability aspects. The top terms suggest an emphasis on assessing corporate sustainability practices and incorporating environmental considerations into evaluation frameworks (

Hansen & Schaltegger, 2018). The inclusion of “Sustainability Balanced Scorecard Knowledge” implies a link between traditional performance metrics and sustainability-focused ones, reflecting a shift toward evaluating not just financial outcomes but also environmental and societal impacts.

Seminal works by

Bieker et al. (

2002),

Figge et al. (

2002), and

Mio et al. (

2022) have highlighted the value of integrating sustainability indicators into corporate strategies. For example,

Asadi Louye et al. (

2026) demonstrated how Iranian hospitals integrated resource consumption and patient care metrics into their SBSC frameworks to enhance environmental management while maintaining healthcare quality.

The mentions of “corporate environmental management” and “digital innovation” suggest that this cluster captures trends where organizations leverage technologies such as big data and IoT to optimize sustainability metrics, as seen in

Zhang et al. (

2023), who analyzed SBSC adoption in China’s logistics sector. In essence, this cluster represents the evolution of performance evaluation systems to include sustainability as a core component of strategic management. Researchers such as

Adams and Frost (

2008),

Hristov et al. (

2019), and

Stavropoulou et al. (

2023), have explored modifications to the existing BSC perspectives, incorporating sustainability metrics within internal processes (e.g., energy efficiency, waste management) and learning and growth (e.g., sustainability training and fostering a socially responsible organizational culture).

Cluster 1—Sustainability Balanced Scorecard

The second cluster is centered around the SBSC, a framework that enhances the traditional balanced scorecard by integrating sustainability dimensions—environmental, social, and governance—into strategic performance management. The SBSC enables organizations to align long-term sustainable development goals with financial, operational, and strategic priorities.

Recent applications underscore its versatility:

Barbosa et al. (

2020b) demonstrated its use in Brazilian manufacturing SMEs, where an SBSC facilitated the alignment of eco-efficiency goals with production targets. In the resource recovery sector, studies such as that by

Zhang et al. (

2023) have combined the SBSC with MCDM techniques like AHP to optimize decisions on waste valorization and logistics. These quantitative methodologies assist businesses in evaluating trade-offs between profitability and ecological or social impact.

The prominence of sustainable development in this cluster underscores SBSC’s ability to balance financial outcomes with societal benefits, enabling organizations to adopt sustainable practices while maintaining competitiveness. The SBSC helps organizations prioritize sustainable practices, address stakeholder demands, and enhance resilience in a resource-constrained world (

Hansen & Schaltegger, 2016,

2018). By systematically linking sustainability objectives to KPIs, the SBSC ensures that sustainability is embedded into both strategic planning and daily operations (

Hahn & Figge, 2018), as evidenced in its adoption by logistics firms in China (

Zhang et al., 2023). This cluster reflects sectors and organizations that are pioneers in adopting sophisticated tools to navigate sustainability challenges.

Cluster 2—Small Business

This cluster highlights the role of small businesses in adopting sustainability practices. Despite significant obstacles such as limited resources and informality (

Barbosa et al., 2020a;

Shields & Shelleman, 2015), the SBSC is emerging as a valuable tool for SMEs. For instance,

Barbosa et al. (

2020b) detailed how Brazilian SMEs incorporated energy efficiency and waste reduction metrics within SBSC frameworks, overcoming integration challenges and enhancing competitiveness.

The presence of terms like “green supply chain management” and “sustainable management” signals rising environmental awareness among small businesses, which are adopting structured frameworks to evaluate and improve their sustainability performance. Applications in sectors like textile SMEs (Iran) and food processing (Brazil) further demonstrate the adaptability of the SBSC to varied small business contexts. Additionally, digitalization trends are enabling SMEs to operationalize the SBSC more effectively using user-friendly dashboards and performance tracking tools. This cluster likely reflects the growing role of small businesses as active agents in achieving sustainability objectives, leveraging methodologies traditionally reserved for large corporations.

In

Figure 10, larger nodes represent the most frequently used terms per year, and the curved lines between them indicate co-occurrence.

As can be seen, the first and second clusters are the clusters with the most frequently used terms. Despite this, all clusters follow the timeline under study and are still very recently reflected in the literature. Cluster 0—Performance Evaluation shows that the literature has evolved to integrate sustainability metrics, allowing companies to align their strategies with long-term goals, mitigate risks, and identify opportunities for sustainable innovation (e.g.,

Mio et al., 2022;

Stavropoulou et al., 2023). In Cluster 2—Small Business, as the literature shows, the BSC has been highlighted as a valuable tool for small businesses, allowing them to overcome the challenges of sustainability integration, improve their competitive advantage, and contribute to a more sustainable future, despite costs and implementation difficulties (e.g.,

Barbosa et al., 2020a).

To conclude, Cluster 1—Sustainability Balanced Scorecard is considered the most recent due to the growing relevance and sophistication of the methodologies used to integrate sustainability into strategic management. The SBSC concept, initially developed to incorporate environmental, social, and governance dimensions into the traditional balanced scorecard, has evolved significantly with the adoption of approaches such as MCDM and AHP. These methodologies enable organizations to assess and balance trade-offs between financial goals and ecological or social impacts, responding to growing demands for corporate responsibility and resilience in the context of limited resources. The recent literature, such as the work of

Hansen and Schaltegger (

2018) and

Hahn and Figge (

2018), highlights the effectiveness of the SBSC in aligning sustainability objectives with the strategic and operational priorities of organizations. This approach is especially relevant in sectors facing complex challenges such as resource recovery and corporate sustainability. Furthermore, the SBSC not only incorporates sustainable practices but ensures that they are systematically integrated into strategic planning and daily operations, strengthening companies’ competitiveness. The recent relevance of this cluster reflects the increasingly widespread adoption of the SBSC in innovative organizations, which are leading the transition to more sustainable practices. These trends show how the SBSC has evolved from a theoretical idea to a widely applied strategic tool, positioning it as an essential element in contemporary management.

The results confirm the SBSC’s effectiveness in promoting strategic alignment with sustainability objectives while emphasizing the need for additional empirical studies to validate its application in specific contexts. The identified international collaborations, particularly between European and Asian institutions, point to the increasing globalization of research in this field. The SBSC framework not only provides a structured approach to monitoring and evaluating sustainability initiatives but also enhances innovation and competitiveness by aligning organizational practices with long-term goals. Despite these advancements, challenges persist, including the definition of relevant indicators and organizational resistance (

Hristov et al., 2019). In particular, SMEs face specific challenges such as organizational resistance and resource constraints, but they can benefit from an adapted SBSC implementation by including metrics tailored to their needs, such as energy efficiency indicators and waste reduction measures (

Stavropoulou et al., 2023). Furthermore, the integration of ESG indicators into the SBSC framework enables SMEs to strengthen their stakeholder reputation and boost their capacity for sustainable innovation—key factors in responding to regulatory pressures and market demands (

Hansen & Schaltegger, 2016). These results highlight that while significant barriers remain, SMEs can leverage the SBSC’s flexibility as a catalyst for achieving both their strategic and sustainability objectives in a practical and integrated manner. Furthermore, the limited integration of sustainability goals with existing management systems requires greater attention, particularly in industries that are less mature regarding sustainable practices.

4.4. Practical Implications and Sectoral Considerations

In the context of SMEs (Cluster 2), the literature highlights recurring challenges such as limited financial and human resources, informality in sustainability practices, and insufficient strategic alignment (

Barbosa et al., 2020a;

Shields & Shelleman, 2015). Despite these constraints, recent studies (e.g.,

Stalmachova et al., 2022) suggest that the SBSC can be operationalized effectively in SMEs by leveraging digital tools and simplified indicator frameworks. Practical recommendations for SMEs include integrating metrics related to energy efficiency, waste reduction, and employee sustainability training into the internal process and learning SBSC perspectives. Furthermore, government agencies and business associations can facilitate adoption by offering subsidized access to digital sustainability dashboards, standardized ESG reporting templates, and targeted training programs. Case examples from manufacturing SMEs in Europe show that digitalization—through smart meters and IoT devices—has enabled the real-time monitoring of energy consumption, directly feeding into SBSC performance reviews.

The performance measurement cluster (Cluster 0) underscores the need to position sustainability indicators at the strategic BSC core rather than as peripheral or compliance-oriented add-ons. Practical implementation requires deliberate alignment of environmental and social metrics with financial targets, creating an integrated value proposition. For example, leading firms in the consumer goods sector have linked reductions in carbon emissions with cost savings and brand equity enhancement, thus reinforcing the financial relevance of ESG goals. Recommended practices include adopting sectoral ESG standards—such as the GRI and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB)—to ensure comparability while customizing specific metrics to reflect the company’s operational realities. Digitalization further supports this process by enabling automated data collection, real-time dashboards, and predictive analytics for sustainability performance.

For large corporations and public sector organizations, the growing application of multi-criterion decision-making methods (e.g., AHP, MCDM) reflects a more advanced approach to embedding sustainability in strategic planning. In these contexts, the SBSC functions not only as a management tool but also as a mechanism for demonstrating accountability, transparency, and legitimacy. However, common barriers such as organizational resistance, a lack of standardized metrics, and coordination difficulties persist. To overcome these, organizations are advised to establish cross-functional sustainability committees, adopt internationally recognized frameworks such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and ensure that stakeholder engagement is embedded in SBSC design. In the public sector, best practices include linking SBSC indicators directly to institutional mandates (e.g., public health, education outcomes) and involving citizens and NGOs in the performance evaluation process, thereby reinforcing social value creation.

Overall, the findings suggest that the SBSC should not be applied as a one-size-fits-all model but adapted to organizational characteristics, sectoral requirements, and technological capabilities. Enabling policies such as public incentives for digital sustainability tools, ESG reporting regulations, and capacity-building initiatives can further support effective SBSC implementation. In doing so, the SBSC can evolve into a dynamic and adaptable tool for aligning sustainability objectives with strategic management practices in all sectors, including those undergoing rapid digital transformation.

4.5. Conceptual Tensions and Structural Debates in SBSC Research

Although SBSC is becoming increasingly important in the academic and management fields, the literature reveals several conceptual tensions and unresolved structural issues that require further analysis. These issues focus particularly on the SBSC architectural configuration, the selection and harmonization of performance indicators and the adaptability of the reference framework to different sectors.

One of the main discussions is centered on the introduction of sustainability into the balanced scorecard model structure. Authors differ on whether sustainability should be presented as a fifth autonomous perspective (

Figge et al., 2002) or whether it should be integrated into the four traditional perspectives (financial, customer, internal processes, and learning and growth). Authors who defend the autonomous model argue that it ensures greater visibility and prioritization of environmental, social, and governance objectives (

Hansen & Schaltegger, 2016). However, this approach has been criticized for potentially isolating sustainability from the organization’s core strategic narrative. The integrated model, on the other hand, promotes consistency by distributing sustainability considerations across existing dimensions, as argued by

Hansen and Schaltegger (

2016). However, this can run the risk of underestimating sustainability unless it is explicitly prioritized in each domain.

A second point of divergence relates to sustainability indicators. Although the SBSC seeks to align strategic objectives with measurable ESG performance, there is still a lack of consensus on the selection of indicators. Studies often adopt sectoral or case-specific metrics, which makes comparison difficult. This issue becomes particularly important in global or multi-sector analyses, where contextual variability further fractures the research fields.

Finally, there is ongoing discussion about the transferability of the SBSC from business organizations to other types of organizations. While some authors propose universal applicability, the literature also emphasizes the barriers to adoption among SMEs, including limited resources, insufficient technical expertise, and resistance to structural change. Public sector organizations face different obstacles, often requiring the adaptation of SBSCs to emphasize legitimacy, transparency, and stakeholder involvement rather than competitive advantage.

These tensions reveal a field in active evolution. To increase theoretical and practical coherence, future researchers should seek to carry out comparative assessments of SBSC models, investigate sector-specific adaptations, and work toward greater standardization of sustainability measurement. In doing so, it will contribute to the maturity of SBSC, both as a conceptual framework and as a practical tool.

To improve the practical application of SBSC, organizations should first carefully evaluate whether sustainability goals are better served by adopting an autonomous fifth perspective or by integrating them into the existing four perspectives. This decision should be guided by the organization’s structure, strategic priorities, and the need for visibility in ESG objectives. Second, when selecting performance indicators, practitioners are advised to combine internationally recognized ESG standards (such as the GRI, Sustainability Accounting Standards Board—SASB, or United Nations Sustainable Development Goals—SDGs) with sector-specific metrics to ensure both comparability and relevance. To enhance adaptability, especially in SMEs and public sector organizations, SBSC frameworks should be simplified where necessary, supported by training programs to build technical expertise, and designed to include stakeholder engagement mechanisms that foster transparency and legitimacy. Finally, organizations should establish regular review and benchmarking processes to refine their SBSCs in line with emerging sustainability practices and evolving sectoral challenges.