Student and Practitioner Cheating: A Crisis for the Accounting Profession

Abstract

:1. A Crisis for the Accounting Profession

The events of the last eighteen plus months have focused a bright light on the profession’s core values: integrity, competence and objectivity. Unfortunately, the failures have rightly caused the public to ask if we have been true to those core values. For the first time in my memory our credibility has been called into question and that is the most troubling consequence of these recent events. In point of fact, our core values are actually the solution and we have to do whatever it takes to live up to those values and to instill them in the next generation of CPAs. The real solution to our crisis in confidence rests with the rank and file CPA. Each CPA has a significant influence in their professional and personal community and the best opportunity to shape opinion. How we live our values on a daily basis will have more impact, good or bad, than any high profile CPAs. I am more concerned about those who make a difference than about those who make headlines.

Leaders in the accounting profession and in academe should focus on calling individuals to excellence. By presenting the importance of high ethical standards, by teaching the importance of personal integrity, we summon current and future accountants to his or her nobility. In doing so, we ensure the future of the accounting profession, which will continue its historic role of fostering the success of the economy and the nation.

2. Professional Guidance

- Refrain from engaging in any conduct that would prejudice carrying out duties ethically.

- Abstain from engaging or supporting any activity that might discredit the profession.

- Contribute to a positive ethical culture and place integrity of the profession above personal interest (IMA, 2017, p. 2).

- A professional accountant shall comply with the principle of integrity, which requires an accountant to be straightforward and honest in all professional and business relationships.

- Integrity involves fair dealing, truthfulness, and having the strength of character to act appropriately, even when facing pressure to do otherwise or when doing so might create potential adverse personal or organizational consequences (IFAC, 2024, p. 20).

- Integrity is an element of character fundamentals to professional recognition. It is the quality from which the public trust derives and the benchmark against which a member must ultimately test all decisions.

- Integrity requires a member to be, among other things, honest and candid within the constraints of client confidentiality. Service and the public trust should not be subordinated to personal gain and advantage. Integrity can accommodate the inadvertent error and an honest difference in opinion; it cannot accommodate deceit or the subordination of principle.

- Integrity is measured in terms of what is right and just. In the absence of specific rules, standards, or guidance or in the face of conflicting opinions, a member should test decisions and deeds by asking: “Am I doing what a person of integrity would do? Have I retained my integrity?” Integrity requires a member to observe both the form and the spirit of technical and ethical standards; the circumvention of those standards constitutes the subordination of judgment (AICPA, 2014, p. 5).

(a) Gather an understanding of culture and governance and their impact on compliance with ethics and independence requirements in accounting firms and, where applicable, their networks (“firms”); (b) Review the extant provisions on organizational firm culture in the Code and consider whether the Code should be further strengthened to reinforce a robust culture of ethical behavior within firms; (c) Raise awareness of the issues relating to and the importance of governance and ethical culture within firms through outreach activities; (d) Develop a report and recommendations to the IESBA.

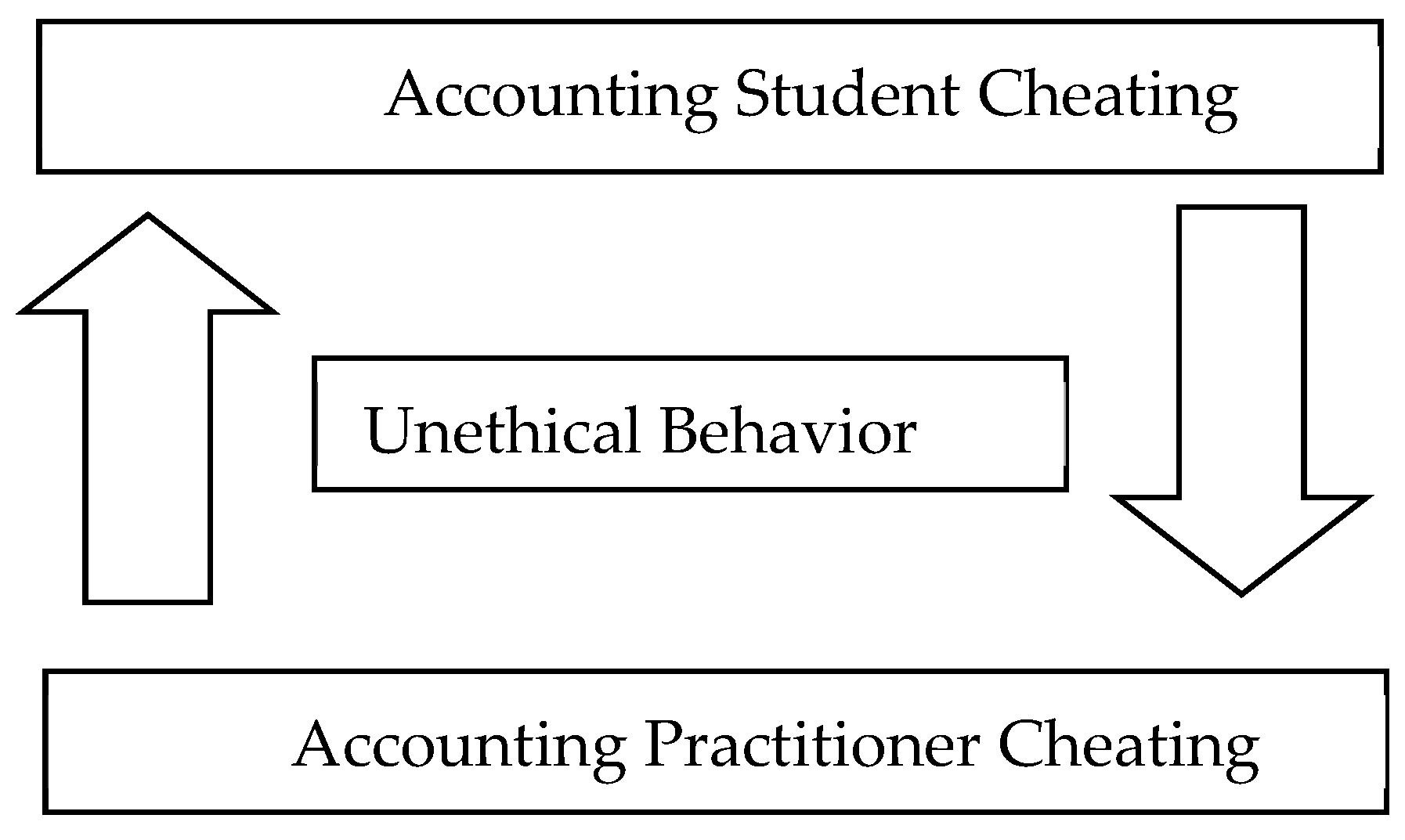

3. The Vicious Cycle of Cheating

4. Student Cheating

…learning is largely due to modeling, imitation, and other social interactions. More specifically, behavior is assumed to be developed and regulated by external stimulus events, such as the influence of other individuals. …Indeed modeling is one of the most pervasive and powerful means of transmitting patterns of behavior: Once observers extract the rules and structure underlying the modeled activities, they can generate new patterns of behavior that conform to those properties but go beyond what they have seen or heard, expanding their knowledge and skills rapidly without having to go through the process of learning response consequences.

5. Practitioner Cheating

Today’s actions demonstrate our resolve to hold accountable those who play fast and loose with the tax code. At some point such conduct passes from clever accounting and lawyering to theft from the people. We simply can’t tolerate flagrant abuse of the law and professional obligations by tax practitioners, particularly those associated with so-called blue chip firms like KPMG, that by virtue of their prominence set the standard of conduct for others. Accountants and attorneys should be the pillars of our system of taxation, not the architects of its circumvention.(IRS, 2005, 29 April, para. 3)

5.1. KPMG

5.2. PwC

5.3. EY

This action involves breaches of trust by gatekeepers within the gatekeeper entrusted to audit many of our Nation’s public companies. It is simply outrageous that the very professionals responsible for catching cheating by clients cheated on the ethics exams of all things and it’s equally shocking that Ernst & Young hindered our investigation of this misconduct. This action should serve as a clear message that the SEC will not tolerate integrity failures by independent auditors who choose the easier wrong over the harder right.

5.4. Deloitte

6. How Accounting Educators Can Respond

7. How Accounting Practitioners Can Respond

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AICPA. ((2014,, December 15)). AICPA code of professional conduct. Available online: https://us.aicpa.org/content/dam/aicpa/research/standards/codeofconduct/downloadabledocuments/2014december15contentasof2016august31codeofconduct.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Alshurafat, H., Al Shbail, M. O., Hamdan, A., Al-Dmour, A., & Ensour, W. (2024). Factors affecting accounting students’ misuse of ChatGPT: An application of the fraud triangle theory. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 22(2), 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, P., & Sundaram, S. (2021). Prevalence, types and reasons for academic misconduct among college students. Journal of Studies in Social Sciences and Humanities, 7(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- APA Dictionary of American Psychology. (n.d.). Social learning theory. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/social-learning-theory (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Ariail, D. L., Cavico, F. J., & Vasa-Sideris, S. (2015). Academic dishonesty in an accounting ethics class: A case study in an accounting ethics class (teaching notes). Journal of the International Academy for Case Studies, 21(6), 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ariail, D. L., Khayati, A., Melnik, M., & Smith, L. M. (2024a). Business and accounting student academic dishonesty: Ethical theory-related rationalizations and cheating perceptions. Research on Professional Responsibility and Ethics in Accounting, 27. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Ariail, D. L., Smith, K. T., & Smith, L. M. (2020). Do United States accountants’ personal values match the profession’s values (ethics code)? Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 35(5), 1047–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariail, D. L., Smith, K. T., & Smith, L. M. (2021). A pedagogy for inculcating professional values in accounting students: Results from an experimental intervention. Issues in Accounting Education, 36(4), 5–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariail, D. L., Smith, K. T., Smith, L. M., Steyn, R., & Khayati, A. (2024b). Improving ethical compliance in accounting and business: An ethics code focused value self-confrontation approach. Research on Professional Responsibility and Ethics in Accounting, 26, 23–54. [Google Scholar]

- Arieli, S., Grant, A. M., & Sagiv, L. (2014). Convincing yourself to care about others: An intervention for enhancing benevolence values. Journal of Personality, 82(1), 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, D. (2014). Look on the bright side: A comparison of positive and negative role models in business ethics education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 13(2), 154–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ball-Rokeach, S. J., Rokeach, M., & Grube, J. W. (1984). The great American values test: Influencing behavior and belief through television. The Free Press, A Division of Macmillan, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Boulianne, E., Lecompte, A., & Fortin, M. (2023). Technology, ethics, and the pandemic: Responses from key accounting actors. Accounting and the Public Interest, 23(1), 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, D. M., Boyle, J. F., & Carpenter, B. W. (2016). Accounting student academic dishonesty: What accounting faculty and administrators believe. The Accounting Educators’ Journal, 26, 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, M. (2003). Unaccountable: How the accounting profession forfeited a public trust. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Brodowsky, G. H., Tarr, E., Ho, F. N., & Sciglimpaglia, D. (2020). Tolerance for cheating from the classroom to the boardroom: A study of underlying personal and cultural drivers. Journal of Marketing Education, 42(1), 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2014). Do role models matter? An investigation of role modeling as an antecedent of perceived ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 122, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundura, A. (1971). Social learning theory. General Learning Press. Available online: https://www.asecib.ase.ro/mps/Bandura_SocialLearningTheory.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Burke, A. B., Polimeni, R. S., & Slavin, N. S. (2007). Academic dishonesty: A crisis on campus. The CPA Journal, 77(5), 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Cheffers, M., & Pakaluk, M. (2007). Understanding accounting ethics (2nd ed.). Allen David Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, M., Kreuze, J., & Langsam, S. (2004). The new scarlet letter: Student perceptions of the accounting profession after Enron. Journal of Education for Business, 79(3), 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, W. J. (1979). Human values, smoking behavior, and public health programs. In M. Rokeach (Ed.), Understanding human values: Individual and societal. The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, P. (2024). Rogue auditors: Dark motivations of the Big 4 accountants in regional sustainability and the creative economy. European Planning Studies, 32(9), 1965–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressey, D. R. (1973). Other people’s money: A study of the social psychology of embezzlement. Patterson Smith Publishing Corporation. (Original work published 1953). [Google Scholar]

- da Costa Diniz, P. K. (2016). Values and their relationship to pro-environmental engagement: A comprehensive and systematic investigation [Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Victoria University of Wellington]. [Google Scholar]

- DOJ. ((2005,) August 9). Department of justice, immediate release. KPMG to pay $456 million for criminal violations in relation to largest-ever tax shelter fraud. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2005/August/05_ag_433.html (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Eagly, A. H., & Koening, A. M. (2021). The vicious cycle linking stereotypes and social roles. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(4), 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grube, J. W., Mayton, D. M., & Ball-Rokeach, S. J. (1994). Inducing change in values, attitudes, and behaviors: Belief system theory and the method of value self-confrontation. Journal of Social Issues, 50(4), 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Dib, J. G., Portales, L., & Heredia-Escorza, Y. (2020). Impact of academic integrity on workplace ethical behaviour. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 16(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havranek, A. ((2020,, October 13)). University of Missouri catch more than 150 students in three cheating incidents. KY3.com. Available online: https://www.ky3.com/2020/10/13/university-of-missouri-catches-more-than-150-students-in-three-cheating-incidents/ (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Hendy, N. T., Montargot, N., & Papadimitriou, A. (2021). Cultural differences in academic dishonesty: A social learning perspective. Journal of Academic Ethics, 19(1), 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirawati, H., Sijabat, Y. P., & Giovanni, A. (2021). Financial literacy, risk tolerance, and financial management of micro-enterprise actors. Society, 9(1), 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R. L. (1998). Basic moral philosophy (2nd ed.). Wadsworth Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- ICAI. (2020). International center for academic integrity. Facts and statistics. Available online: https://academicintegrity.org/resources/facts-and-statistics (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- IESBA. ((2025,, February)). Firm culture and governance: IESBA firm culture and governance working group final report. Available online: https://www.ethicsboard.org/publications/iesba-firm-culture-and-governance-working-group-final-report (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- IFAC. (2024). Handbook of the international code of ethics for professional accountants. Available online: https://ifacweb.blob.core.windows.net/publicfiles/2024-08/2024%20IESBA%20Handbook%20of%20the%20International%20Code%20of%20Ethics%20for%20Professional%20Accountants.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- IIA. (n.d.). The IIA global standard of integrity. Available online: https://www.theiia.org/en/standards/what-are-the-standards/mandatory-guidance/code-of-ethics/ (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- IMA. (2017). IMA statement of ethical professional practice. Available online: https://www.imanet.org/career-resources/ethics-center/statement (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- IRS. ((2005,) April 29). Internal revenue service IRS.gov. Statement by IRS commissioner Mark W. Everson regarding KPMG corporate fraud case delivered at the justice department. Available online: https://www.corporatecrimereporter.com/eversonstatement.htm (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Jones, J. M. (2002, December 4). Effects of year’s scandals evident in honesty and ethics ratings. Gallup Poll News Service Report. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/1654/honesty-ethics-professions.aspx (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Kelly, M., Smith, K. J., & Emerson, D. (2022). Perceptions among UK accounting and business students as to the ethicality of using assignment assistance websites. The Accounting Educators’ Journal, 32, 81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Klimek, J., & Wenell, K. (2011). Ethics in accounting: An indispensable course? Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 15(4), 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Loeb, L. ((2021,, March 30)). Cal State LA was caught in a large-scale cheating scandal, but it’s not alone. Express Newspaper & Magazine. Available online: https://goldengatexpress.org/97004/campus/cal-state-la-was-caught-in-a-large-scale-cheating-scandal-but-its-not-alone/ (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Lungariello, M. ((2021,, May 10)). Dartmouth cheating scandal came after students were tracked online. New York Post. Available online: https://nypost.com/2021/05/10/dartmouth-cheating-scandal-came-after-students-tracked-online/ (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Ma, Z. (2013). Business students’ cheating in classroom and their propensity to cheat in the real world: A study of ethicality and practicality in China. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 2, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, G. R., Pakizeh, A., Cheung, W., & Rees, K. J. (2009). Changing, priming, and acting on values: Effects via motivational relations in a circular model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(4), 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malz, A. M. (2011). Financial risk management: Models, history, and institutions. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Mayville, E. A. (1997). The utilization of value self-confrontation in increasing employment opportunities for the mentally ill [Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of the Pacific]. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, D. L., Butterfield, K. D., & Trevino, L. K. (2006). Academic dishonesty in graduate business programs: Prevalence, causes, and proposed action. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(3), 294–305. [Google Scholar]

- McCombs School of Business. (n.d.). Moral relativism. Available online: https://ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu/glossary/moral-relativism (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Merriam-Webster. (2024). Vicious circle. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/vicious%20circle (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Mintz, S. M., & Miller, B. (2023). Ethical obligations and decision making in accounting: Text and cases (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Moberg, D. J. (2000). Role models and moral exemplars: How do employees acquire virtues by observing others? Business Ethics Quarterly, 10(3), 675–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, M., & Shah, A. (2023). Academic dishonesty: An exploratory study of traditional versus non-traditional students. Research in Higher Education Journal, 43, 1–12. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1382877.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Mushtaque, A. (2023). 20 most trusted professions in America. Yahoo!Finance. Available online: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/20-most-trusted-professions-america-094909043.html (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Neto, A. V. D. S., Bonfim, M. P., & Silva, C. A. T. (2024). Academic dishonesty: Motivations of accounting students. Revista Ambiente Contabil, 16(1), 370–392. Available online: https://periodicos.ufrn.br/ambiente/article/view/34957 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Neville, L. (2012). Do economic equality and generalized trust inhibit academic dishonesty? Evidence from state-level search-engine queries. Psychological Science, 23(4), 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PCAOB. (n.d.-a). PCAOB auditing and professional practice standards, rule 3500T. Available online: https://pcaobus.org/about/rules-rulemaking/rules/section_3 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- PCAOB. (n.d.-b). PCAOB QC section 20. PCAOB system of quality control for a CPA firm’s accounting and auditing practice. Available online: https://pcaobus.org/oversight/standards/qc-standards/details/QC20 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- PCAOB. (2021). PCAOB release No. 105-2021-008, September 13, 2021. Order instituting disciplinary proceedings, making findings, and imposing sanc-tions in the matter of KPMG. Available online: https://pcaobus.org/enforcement/decisions/documents/105-2021-008-kpmg-australia.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- PCAOB. (2022a). PCAOB release No. 105-2022-002, February 24, 2022. Order instituting disciplinary proceedings, making findings, and imposing sanc-tions in the matter of PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (PwC Canada). Available online: https://assets.pcaobus.org/pcaob-dev/docs/default-source/enforcement/decisions/documents/105-2022-002_pwc-canada.pdf?sfvrsn=7913aea3_4 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- PCAOB. (2022b). PCAOB release No. 105-2022-032, December 6, 2022. Order instituting disciplinary proceedings, making findings, and imposing sanc-tions in the matter of KPMG LLP (United Kingdom). Available online: https://assets.pcaobus.org/pcaob-dev/docs/default-source/enforcement/decisions/documents/105-2022-032-kpmg-uk.pdf?sfvrsn=e941fbab_4 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- PCAOB. (2024a). PCAOB release No. 105-2024-022, April 10, 2024. Order instituting disciplinary proceedings, making findings, and imposing sanctions in the matter of KPMG Accountants N.V. [KPMG Netherlands]. Available online: https://assets.pcaobus.org/pcaob-dev/docs/default-source/enforcement/decisions/documents/105-2024-022-kpmg-netherlands.pdf?sfvrsn=ce46c211_2 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- PCAOB. (2024b). PCAOB release No. 105-2024-024, April 10, 2024. Order instituting disciplinary proceedings, making findings, and imposing sanctions in the matter of Imelda & Rekan (DT Indonesia). Available online: https://assets.pcaobus.org/pcaob-dev/docs/default-source/enforcement/decisions/documents/105-2024-024-dt-indonesia.pdf?sfvrsn=77f4a344_2 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- PCAOB. (2024c). PCAOB release No. 105-2024-025, April 10, 2024. Order instituting disciplinary proceedings, making findings, and imposing sanctions in the matter of Navarro Amper & Co. [DT Philippines]. Available online: https://assets.pcaobus.org/pcaob-dev/docs/default-source/enforcement/decisions/documents/105-2024-025-dt-philippines.pdf?sfvrsn=6cd202b_2 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Perry, G. M., & Nixon, C. J. (2005). The influence of role models on negotiation ethics of college students. Journal of Business Ethics, 62, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rujoiu, O., & Rujoiu, V. (2014, November). Academic dishonesty and workplace dishonesty. An overview. In Proceedings of the International Management Conference (Vol. 8, pp. 928–938). Faculty of Management, Academy of Economic Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Sarbanes-Oxley act of 2002. (2002). Public law 107-204; 107th congress; enacted July 20, 2002. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/about/laws/soa2002.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Schwartz, S. H., & Inbar-Saban, N. (1988). Value self-confrontation as a method to aid in weight loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(3), 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SEC. (2019). United States of America before the securities and exchange commission in the matter of KPMG LLP respondent. Securities exchange act of 1934, Release No. 86118/June 17, 2019; Accounting and auditing enforcement release No. 4051/June 17, 2019; Administrative pro-ceeding file No. 3-19203. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/files/litigation/admin/2019/34-86118.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- SEC. (2022a). Ernst & young to pay $100 million penalty for employees cheating on CPA ethics exam and misleading investigation. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022-114 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- SEC. (2022b). Securities and exchange commission, accounting and enforcement in the matter of ernst & young LLP, June 28, 2022. SEC release No. 95167; Accounting and enforcement release No. 4313. Administrative proceeding file No. 3-20911. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/files/litigation/admin/2022/34-95167.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Sims, R. L. (1993). The relationship between academic dishonesty and unethical business practices. Journal of Education for Business, 68(4), 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirdeshmukh, G. ((2021,, April 7)). Academic misconduct spikes during pandemic, professors offer solutions. The Chronicle. Available online: https://www.dukechronicle.com/article/2021/04/duke-university-academic-misconduct-student-professor-cheating-stress (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Smith, L. M. (2003). A Fresh Look at Accounting Ethics. Accounting Horizons, 17(1), 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stogner, J. M., Miller, B. L., & Marcum, C. D. (2013). Learning to e-cheat: A criminological test of internet facilitated academic cheating. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 24(2), 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nunspeet, F., & Ellemers, N. (2024). Regulating other people’s moral behaviors: Turning vicious cycles into virtuous cycles. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 27(1), 196–213. [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez, M., Andre, C., Shanks, T., & Meyer, M. J. (1992). Ethical relativism. Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Available online: https://www.scu.edu/ethics/ethics-resources/ethical-decision-making/ethical-relativism/ (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Voynich, S. S. ((2003,, September 13)). (Chair elect, American Institute of Public Accountants, New York, NY, USA). Personal Communication with Dr. Donald L. Ariail. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T. (2022, July 13). One in six UK students admits cheating in online exams. Times Higher Education. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/one-six-uk-students-admits-cheating-online-exams (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Wolfe, D. T., & Hermanson, D. R. (2004). The fraud diamond: Considering the four elements of fraud. The CPA Journal, 74(12), 38. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L., Mao, H., Compton, B. J., Peng, J., Fu, G., Fang, F., Heyan, G. D., & Lee, K. (2022). Academic dishonesty and its relations to peer cheating and culture: A meta-analysis of the perceived peer cheating effect. Education Research Review, 36, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ariail, D.L.; Smith, L.M.; Khayati, A. Student and Practitioner Cheating: A Crisis for the Accounting Profession. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050285

Ariail DL, Smith LM, Khayati A. Student and Practitioner Cheating: A Crisis for the Accounting Profession. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(5):285. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050285

Chicago/Turabian StyleAriail, Donald L., Lawrence Murphy Smith, and Amine Khayati. 2025. "Student and Practitioner Cheating: A Crisis for the Accounting Profession" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 5: 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050285

APA StyleAriail, D. L., Smith, L. M., & Khayati, A. (2025). Student and Practitioner Cheating: A Crisis for the Accounting Profession. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(5), 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050285