Impact of Management Indicators on the Business Performance of Hotel SMEs in Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: Does the use of management indicators improve decision-making among hotel SME managers?

- RQ2: Do management indicators allow better investment and financing decision-making for hotel SMEs?

- RQ3: Does the use of financial information allow for better decisions to be made by hotel SMEs?

- RQ4: Does management control in hotel SMEs lead to better business performance?

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Question

2.1. Business Performance of Hotel SMEs

2.2. The Importance of Indicators Regarding Business Management in Hotel SMEs

2.3. Management Control Theory

2.4. Variable Development

2.4.1. Investment

2.4.2. Profitability

2.4.3. Funding Sources

2.4.4. Operating Indicators in Hotel SMEs

2.4.5. Use of Financial Information

2.5. Hypothesis Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurements

3.2. Content Validity

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Index Verification

3.6. Independent Factors

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Company Profile

4.2. Measurement Model

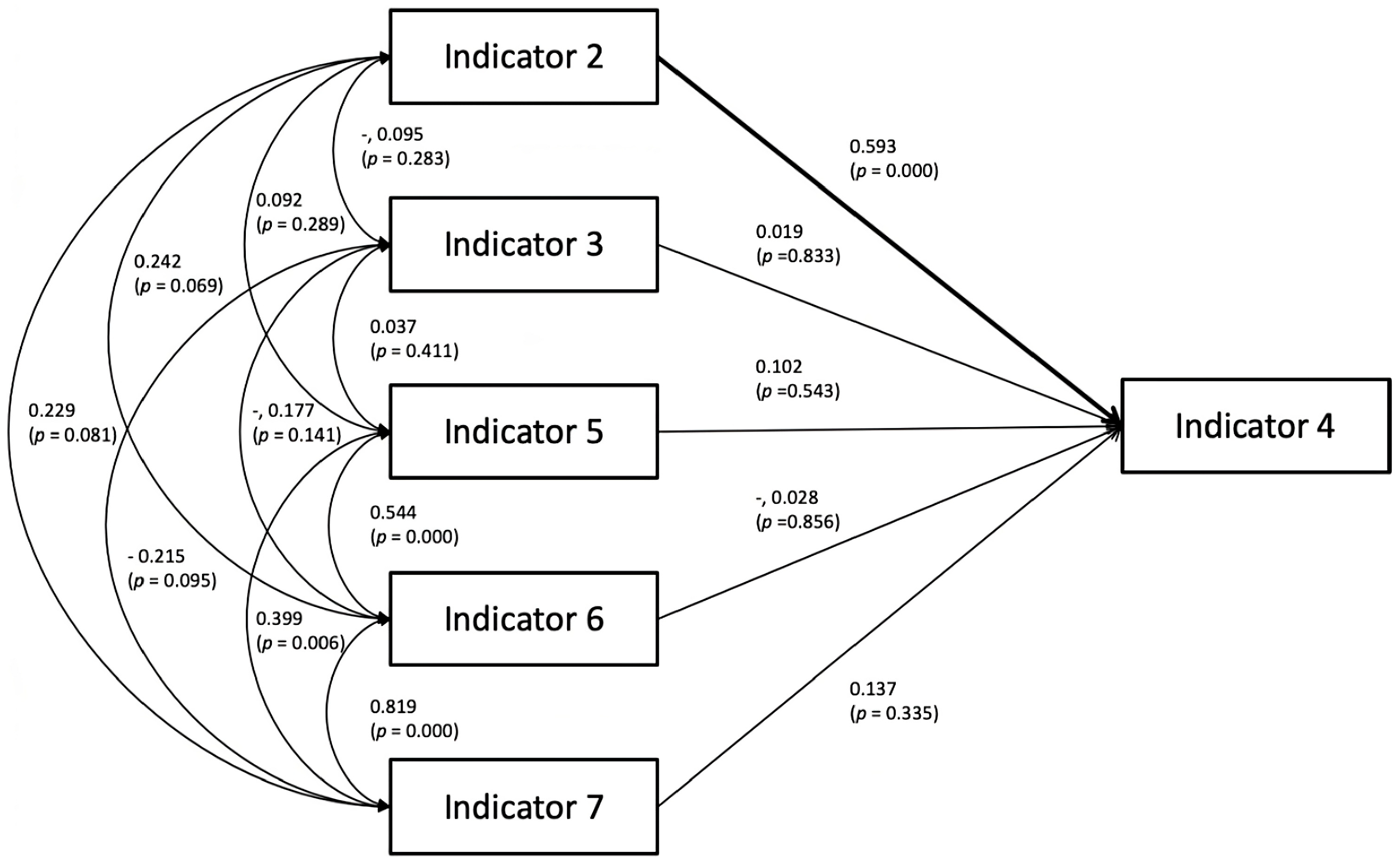

4.3. Multiple Linear Regression (MLR)

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agiomirgianakis, G., Magoutas, A., & Sfakianakis, G. (2013). Determinants of profitability in the greek tourism sector revisited: The impact of the economic crisis. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 1(1), 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhaafri, H. S., Al-Swidi, A. K., & Al-Ansi, A. A. (2016). Organizational excellence as the driver for organizational performance: A study on dubai police. International Journal of Business and Management, 11(2), 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M., Yan, M., & Okumus, F. (2021). Coopetition strategies for competitive intelligence practices-evidence from full-service hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 99(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shourah, S., & Shourah, A. (2020). An examination between total quality management and hotel financial performance: Evidence from jordanian international hotels. International Journal of Information and Decision Sciences, 12(1), 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altin, M., Schwartz, Z., & Uysal, M. (2017). Where you do it matters: The impact of hotels revenue-management implementation strategies on performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 67(1), 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación Mexicana de Hoteles en Yucatan. (2022). Informe anual. COPSA. [Google Scholar]

- Asree, S., Zain, M., & Razalli, R. (2010). Influence of leadership competency and organizational culture on responsiveness and performance of firms. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(4), 500–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barradas, M., Rodríguez, J., & Maya, I. (2021). Organizational performance. A theoretical review of its dimensions and measurement form. Revista de Estudios en Contaduría, Administración e Infomática, 10(28), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, E., & Neely, A. (2012). Managing performance in turbulent times: Analytics and insight. John Wiley & Son Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, A., Broadbent, J., & Otley, D. (1998). Management control theory. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolli, M., Roark, G., Urrutia, S., & Chiodi, F. (2017). Revisión de modelos de madurez en la medición del desempeño. INGE CUC, 13(1), 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. (1970). Back-Translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkov, V., Goubko, M., Korgin, N., & Novikov, D. (2015). Theory of control in organization. Plamar. [Google Scholar]

- Caban-Garcia, M., Ríos Figueroa, C., & Petruska, K. (2017). The impact of culture on internal control weaknesses: Evidence from firms that cross-list in the U.S. Journal of International Accounting Research, 16, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, J. (2024). El proceso administrativo y la toma de decisiones en hoteles de categoría 3 estrellas. Gestionar: Revista de Empresa y Gobierno, 3(4), 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F., Gomes, C., Malheiros, C., & Lima Santos, L. (2024). Hospitality environmental indicators enhancing tourism destination sustainable management. Administrative Sciences, 14(3), 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps, J., & Luna-Arocas, R. (2012). A matter of learning how human resources affect organizational performance. British Journal of Management, 23, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, G. (2012). Hospitality competitiveness measurement system. Journal of Global Business and Technology, 8(2), 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Caro, M., Leyva, C., & Vela, R. (2011). Calidad de las tecnologías de la información y competitividad en hoteles de la península de yucatán. Contaduría y Administración, 235, 121–146. [Google Scholar]

- Cerny, C., & Kaiser, H. (1977). A study of a measure of sampling adequacy for factor-analytic correlation matrices. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1(12), 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X., Fu, S., Sun, J., Bilgihan, A., & Okumus, F. (2019). An investigation on online reviews in sharing economy driven hospitality platforms: A viewpoint of trust. Tourism Management, 71, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, G., Azcué, I., Pérez, A., & Varisco, C. (2020). Pymes turísticas. Aportes conceptuales para su estudio. Universidad Nacional de Mar de Plata. [Google Scholar]

- Dev, C. (2020). The future of hospitality management programs: A wakeup call. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 44(8), 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrić, M., Žiković, I., & Arbula, A. (2019). Profitability determinants of hotel companies in selected mediterranean countries. Economic Research, 32(1), 1977–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru, T., & Bulut, U. (2018). Is tourism an engine for economic recovery? Theory and empirical evidence. Tourism Management, 67, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraan, S., Crissien, E., Virviesca, J., & García, J. (2017). Estrategias gerenciales para la formación de equipos de trabajos en empresas constructoras del caribe colombiano. Revista Espacios, 13(38), 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Estupiñán, R. (2020). Análisis financiero y de gestión. Ecoe Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraz, P., Román, C., & Cibrán, J. (2013). Planificación financiera. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Gitman, L. (2003). Principios de administración financiera. Pearson Educación de México, S.A. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, C., Aristizabal, C., & Fuentes, D. (2017). Importancia de la información financiera para el ejercicio de la gerencia. Desarrollo Gerencial, 9(2), 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guajardo Cantú, G. (2002). Contabilidad financiera (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 970103354X, 9789701033548. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D., & Chi, C. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality industry. Review of the Current Situations and a Research Agenda, 29(5), 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajar, I. (2015). The effect of business strategy on innovation and firm performance in the small industrial sector. International Journal of Engineering and Science, 4(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, C. (2017). New performance indicators for restaurant revenue management: ProPASH and ProPASM. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 61, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, N., Morosan, C., & DeFranco, A. (2015). The other side of technology adoption: Examining the relationships between e-commerce expenses and hotel performance. International Journal of Hosptality Management, 45, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Tecnológico Hotelero. (2017). Innovación en el sector hotelero. Recuperado de. [Google Scholar]

- Jokipii, A. (2010). Determinants and consequences of internal control in firms: A contingency theory based analysis. Journal of Management Governance, 14, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantis, H., Postigo, S., Federico, J., & Tamborini, M. (2020). El Surgimiento de emprendedores de base universitaria: ¿en qué se diferencian? Evidencias empíricas para el caso de argentina. LITTEC, 35(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M., & Hefny, M. (2019). Systematic assessment of theory-based research in hospitality management: A prelude to building theories. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 43(4), 464–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R., & Sharma, C. (2023). Does financial development raise tourism demand? A cross-country panel evidence. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 47(6), 1040–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Kim, S., & Lee, M. (2022). What to sell and how to sell matters: Focusing on luxury hotel properties’ business performance and efficiency. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 63(1), 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T., Kim, W., Park, S., Lee, G., & Jee, B. (2012). Intellectual capital and business performance: What structural relationships do they have in upper-upscale hotels? International Journal of Tourism Research, 14(4), 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, A. (1956). Els fonaments de la teoria de la probabilitat. Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lado, R., Vivel, M., & Otero, L. (2017). Determinants of TRevPAR: Hotel, management and tourist destination. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(12), 3138–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likert, R. (1976). The human organization. McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Lima Santos, L., Gomes, C., Faria, A. R., Lunkes, R. J., Malheiros, C., Silva da Rosa, F., & Nunes, C. (2016). Contabilidade de gestão hoteleira. ATF–Edições Técnicas. ISBN 978-989-98944-3-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lima Santos, L., Gomes, C., & Malheiros, C. (2020a). Achieving a competitive management in micro and small independent hotels. In S. Teixeira, & J. Ferreira (Eds.), Multilevel approach to competitiveness in the global tourism industry (pp. 229–255). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lima Santos, L., Gomes, C., Malheiros, C., & Lucas, A. (2021). Impact factors on portuguese hotels’ liquidity. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(4), 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima Santos, L., Malheiros, C., Gomes, C., & Guerra, T. (2020b). TRevPAR as hotels performance evaluation indicator and influecing factors in Portugal. Euro-Asia Tourism Studies Journal, 1(1), 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Meng, W., Mingers, J., Tang, N., & Wang, W. (2012). Developing a performance management system using soft systems methodology: A chinese case study. European Journal of Operational Research, 223(2), 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H. (2021). Optimization of hotel financial management information system based on computational intelligence. Hindawi, 20(21), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Granados, V., & Mancilla Rendón, M. (2010). Control en la administración para una información financiera confiable. Contabilidad Y Negocios, 5(9), 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroy, L., & Simbaqueba, N. (2017). La importancia de los indicadores de gestión en las organizaciones Colombianas. Equidad y Desarrollo, 43(1), 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsalve, C., & Hernández, S. (2015). Gestión de la calidad del servicio en la hotelería como elemento clave en el desarrollo de destinos turísticos sostenibles: Caso Bucaramanga. Revista EAN, 1(78), 160–173. [Google Scholar]

- Montero, R. (2016). Modelos de regresión lineal múltiple. Documentos de trabajo en economía aplicada. Universidad de Granada. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, C., Navarrete, M., & Membreño, J. (2020). Impacto del turismo en la hotelería en México. Journal of Tourism and Heritage Research, 3(3), 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napierala, T., & Birdir, K. (2017). Competition in hotel industry: Theory, evidence and business practice. EJTHR, 10(3), 200–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noe, R., Clarke, A., & Klein, H. (2014). Learning in the twenty-first-century workplace. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 245–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A., & Bojorquez, M. (2021). Competitiveness and financial management in SMEs hotel business in Yucatan, Mexico. Equidad y Desarrollo, 37, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peteraf, M. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristić, Ţ., & Komazec, S. (2011). Globalni finansijski menadţment. EtnoStil. [Google Scholar]

- Rohvein, C., Paravie, D., Urrutia, S., Nunes, D., & Ottogali, D. (2020). Metodología de evaluación del nivel de competitividad de las pymes. Ciencias Estratégicas, 21(29), 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Rummler, G., & Brache, A. (2013). Improving performance: How to manage the white space on the organization chart. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastián, J., Grünewald, L., & Cannizzaro, E. (2000). MiPyMEs turísticas. Perfil general de las mipymes familiares. Fundación Turismo para Todos. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, R., Kozitska, N., Oliveira, C., Oliveira, M., & Machado-Santos, C. (2021). An overview of management control theory. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 20(2), 36–53. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H., & Wei, W. (2024). Environmental practices and firm performance in the hospitality industry: Does national culture matter? Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 49(3), 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C., & Jang, S. (2017). Revisit to the Determinants of capital structure: A comparison between lodging firms and software firms. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 26(1), 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeremes, P., & Tzeremes, N. (2021). Productivity in the hotel industry: An order-α malmquist productivity indicator. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 45(1), 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeri, M. (2022). Tourism risk: Crisis and recovery management. Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Vivel-Búa, M., & Lado-Sestayo, R. (2023). Contagion effect on business failure: A spatial analysis of the hotel sector. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 47(3), 482–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujović, S., & Arsić, L. (2018). Financing in tourism. Basic sources of financing the accommodation offer. Silver & Smith Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A., Kim, S., Liu, Y., & Grace Baah, N. (2023). COVID-19 research in hospitality and tourism: Critical analysis, reflection, and lessons learned. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 49(1), 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Zhang, L., Baker, T., Harrington, R., & Marlowe, B. (2019). Drivers of degree of sophistication in hotel revenue management decision support systems. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 79, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. (2019). Effects of the size of acquisition on a hotel group’s financial performance. Journal of Hospitality Financial Management, 27(1), 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., & Xie, J. (2023). Influence of tourism seasonality and financial ratios on hotels’ exit risk. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 47(4), 714–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Section | KMO | p-Value Bartlett Test | Percentage of Explained Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of financial information | 0.813 | 0.000 | 75.0 |

| Investment | 0.788 | 0.000 | 80.3 |

| Operating indicators | 0.805 | 0.000 | 68.9 |

| Financing sources | 0.777 | 0.000 | 79.8 |

| Profitability | 0.777 | 0.000 | 55.3 |

| Section | Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Use of financial information | 0.974 |

| Investment | 0.984 |

| Operating indicators | 0.974 |

| Financing sources | 0.984 |

| Profitability | 0.960 |

| General | 0.989 |

| Variables | Authors |

|---|---|

| Investment | Dimitrić et al. (2019). |

| Profitability | Caro et al. (2011); Carmona (2012); Agiomirgianakis et al. (2013) |

| Funding sources | Ristić and Komazec (2011); Vujović and Arsić (2018) |

| Operating indicators | Tang and Jang (2017); Lado et al. (2017); Dimitrić et al. (2019); Lima Santos et al. (2020b) |

| Financial information | Martín Granados and Mancilla Rendón (2010); Duraan et al. (2017); Gomez et al. (2017) |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | Collinearity Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard Error. | Beta | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 28.312 | 9.991 | 2.834 | 0.007 | 8.069 | 48.555 | |||

| Inds2 Financial information | 0.593 | 0.119 | 0.635 | 4.996 | 0.000 | 0.352 | 0.833 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Inds3 Funding sources | 0.019 | 0.090 | 0.028 | 0.212 | 0.833 | −0.164 | 0.202 | 0.930 | 1.075 | |

| Inds5 Investment | 0.102 | 0.165 | 0.096 | 0.615 | 0.543 | −0.235 | 0.438 | 0.681 | 1.469 | |

| Inds6 Operating indicators | −0.028 | 0.152 | −0.045 | −0.183 | 0.856 | −0.337 | 0.282 | 0.269 | 3.713 | |

| Inds7 Profitability | 0.137 | 0.140 | 0.222 | 0.979 | 0.335 | −0.148 | 0.422 | 0.322 | 3.106 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez Brito, A.E.; Bojórquez Zapata, M.I.; Lima Santos, L.; Gomes, C. Impact of Management Indicators on the Business Performance of Hotel SMEs in Mexico. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050271

Pérez Brito AE, Bojórquez Zapata MI, Lima Santos L, Gomes C. Impact of Management Indicators on the Business Performance of Hotel SMEs in Mexico. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(5):271. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050271

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez Brito, Antonio Emmanuel, Martha Isabel Bojórquez Zapata, Luís Lima Santos, and Conceição Gomes. 2025. "Impact of Management Indicators on the Business Performance of Hotel SMEs in Mexico" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 5: 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050271

APA StylePérez Brito, A. E., Bojórquez Zapata, M. I., Lima Santos, L., & Gomes, C. (2025). Impact of Management Indicators on the Business Performance of Hotel SMEs in Mexico. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(5), 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050271