Impression Management Tactics in the Chairperson’s Statement: A Systematic Literature Review and Avenues for Future Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose

1.2. Background

1.3. Problem Statement

1.4. Contribution

2. Method

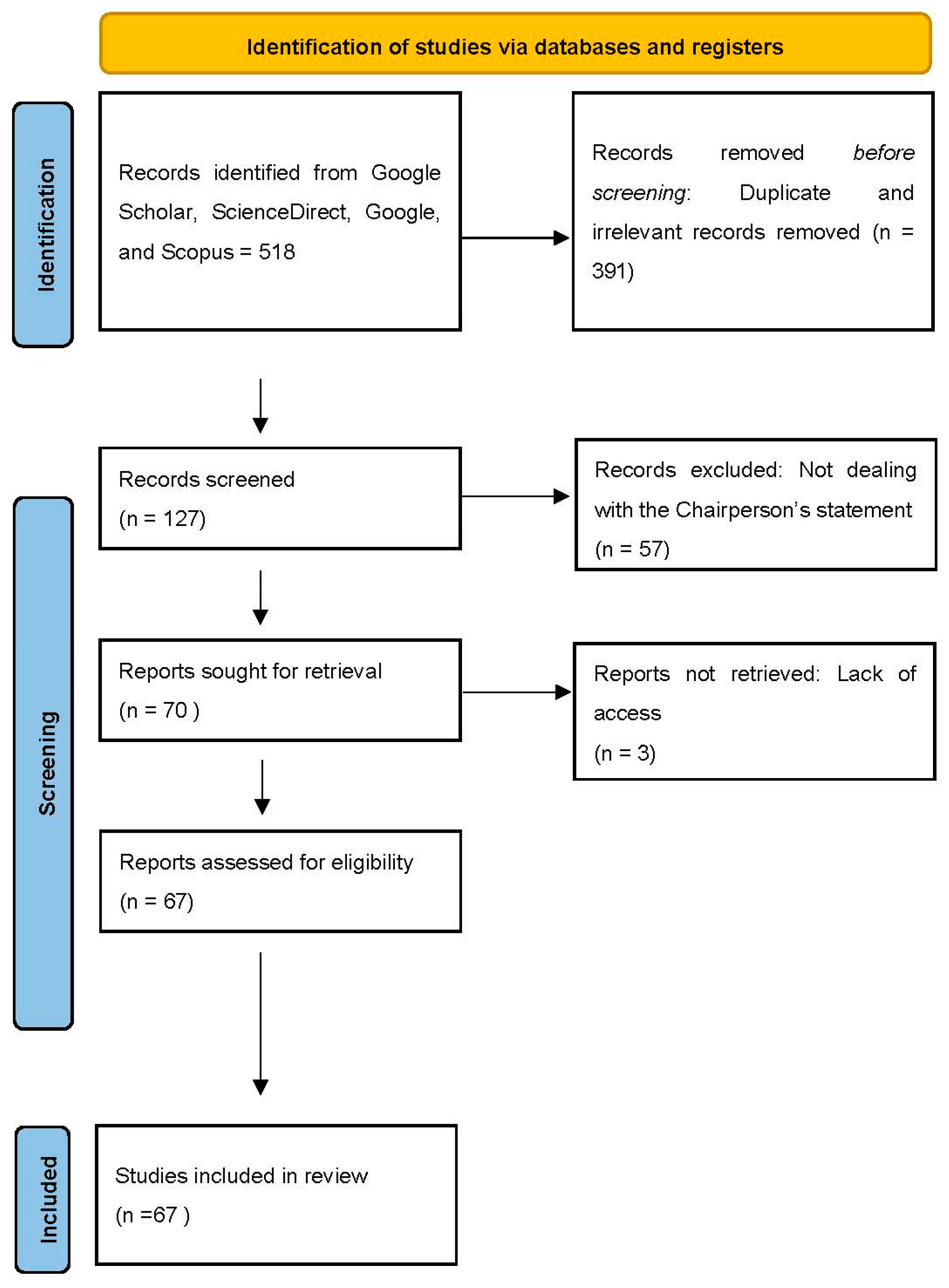

2.1. Stage 1: Selection of Research

2.2. Stage 2: Design of Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Stage 3: Study Identification

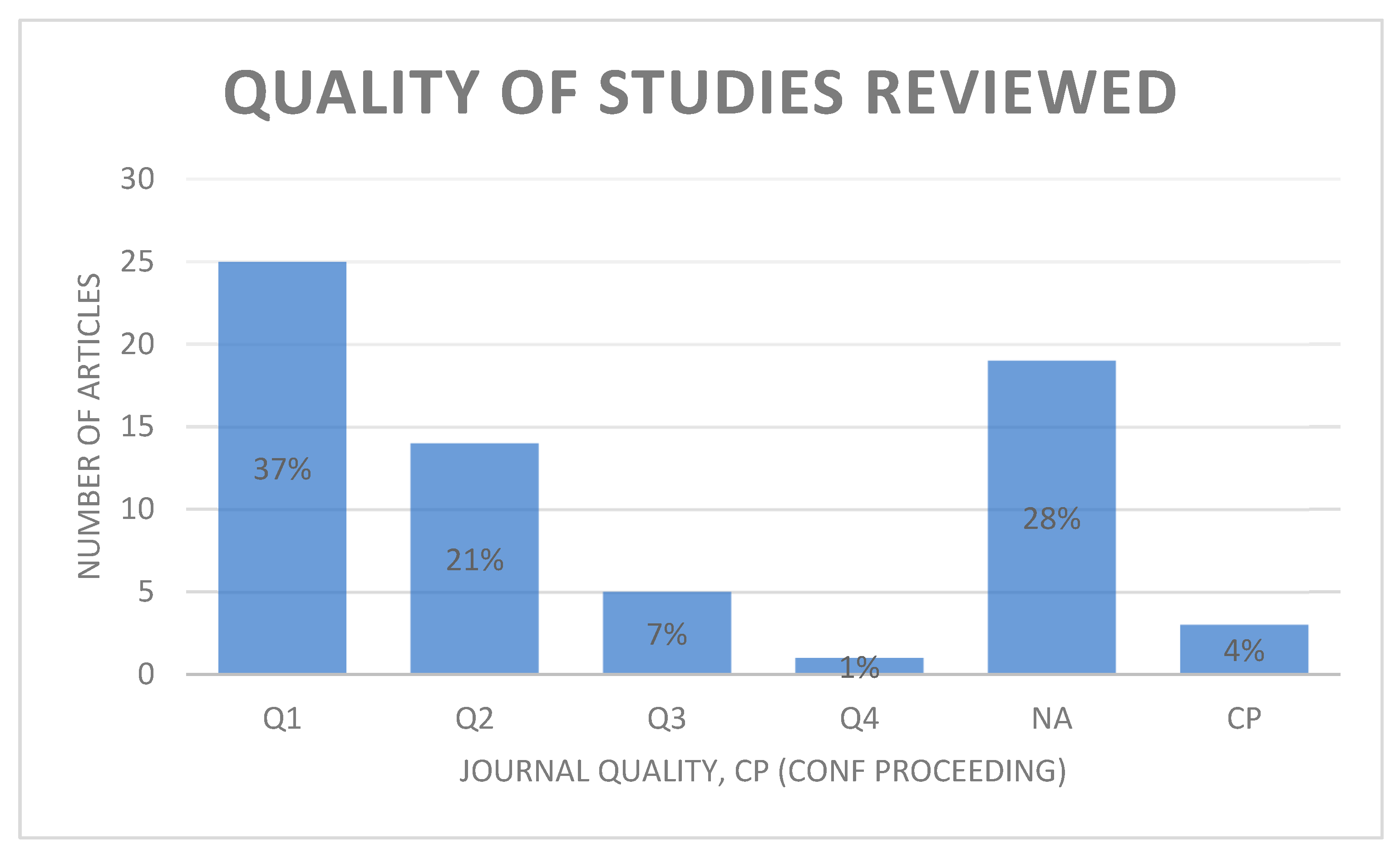

2.4. Stage 4: Study Quality Examination

2.5. Stage 5: Extraction of Data

2.6. Stage 6: Synthesis of Data

3. Results

Descriptive Analysis of the Identified and Reviewed Literature

4. IM Tactics

4.1. Readability

4.2. Textual Characteristics

4.3. Culture, Legal Systems, and Capital Markets

4.4. Paratext

4.5. Intertextuality

4.6. Retrospective Sense-Making

4.7. Obscure Language

4.8. Language Tone

4.9. Self-Serving Attribution

4.10. Photographs

4.11. Impersonalisation and Evaluation

4.12. Forward-Looking Statements

4.13. Graphs

5. Integrative Conceptual Framework

6. Research Gaps

6.1. Audit/Verifiability of CS

6.2. Standardisation of Voluntary Narrative Disclosures

6.3. Perceptions of CS Users

6.4. Culture as Determinant of the Use of IM

6.5. Use of Artificial Intelligence to Detect IM

6.6. IM Use During Crises

6.7. Longitudinal Research Design

6.8. The Actual Preparers of CSs

6.9. Studies Based on Primary Data

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SLR | Systematic literature review |

| IM | Impression management |

| CS | Chairperson’s statement |

| CEO | Chief executive officer |

References

- Abhayawansa, S. (2011). A methodology for investigating intellectual capital information in analyst reports. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 12(3), 446–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, W. (2001). Inertia in the attributional content of annual accounting narratives. European Accounting Review, 10(1), 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, W. (2005). Picking up the pieces: IM in the retrospective attributional framing of accounting outcomes. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 30(6), 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I. U., & Salat, A. (2019). A thematic analysis of chairman’s statement of the commercial banks of Bangladesh. Barishal University Journal (Part-3), A Journal of Business Studies, 5(2), 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Alaka, H. A., Oyedele, L. O., Owolabi, H. A., Kumar, V., Ajayi, S. O., Akinade, O. O., & Bilal, M. (2018). Systematic review of bankruptcy prediction models: Towards a framework for tool selection. Expert Systems with Applications, 94, 164–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Lawati, H., Hussainey, K., & Sagitova, R. (2023). Forward-looking disclosure tone in the chairman’s statement: Obfuscation or truthful explanations. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management, 31(5), 838–863. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sayani, Y. M., & Al-Matari, E. M. (2023). Corporate governance characteristics and IM in financial statements. A further analysis. Malaysian evidence. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1), 2191431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sayani, Y. M., Mohamad Nor, M. N., & Amran, N. A. (2020). The influence of audit committee characteristics on IM in chairman statement: Evidence from Malaysia. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1774250. [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris, E., & Pearson, A. (2014). The systematic review: An overview. AJN The American Journal of Nursing, 114(3), 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, V., Pei, B. K., & Steinbart, P. J. (2002). IM with graphs: Effects on choices. Journal of Information Systems, 16(2), 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasakou, V., & Hussainey, K. (2014). The perceived credibility of forward-looking performance disclosures. Accounting and Business Research, 44(3), 227–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, S. A., & Chandler, R. A. (1997). The corporate report and the private shareholder: Lee and Tweedie twenty years on. The British Accounting Review, 29(3), 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayerlein, L., & Davidson, P. (2012). The influence of connotation on readability and obfuscation in Australian chairman addresses. Managerial Auditing Journal, 27(2), 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, V. (2014). Accounting narratives and the narrative turn in accounting research: Issues, theory, methodology, methods and a research framework. The British Accounting Review, 46(2), 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, V., Dhanani, A., & Jones, M. J. (2008). Investigating presentational change in UK annual reports: A longitudinal perspective. The Journal of Business Communication, 45(2), 181–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, V., & Jones, M. J. (1992). The use and abuse of graphs in annual reports: Theoretical framework and empirical Study. Accounting and Business Research, 22(88), 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, M. J., Clatworthy, M. A., & Jones, M. J. (2004). The prediction of profitability using accounting narratives: A variable-precision rough set approach. Intelligent Systems in Accounting, Finance & Management: International Journal, 12(4), 227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Bhana, N. (2009). The chairman’s statements and annual reports: Are they reporting the same company performance to investors? Investment Analysts Journal, 38(70), 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckel, A., Hörisch, J., & Tenner, I. (2021). A systematic literature review of crowdfunding and sustainability: Highlighting what really matters. Management Review Quarterly, 71, 433–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, N. M., & Merkl-Davies, D. M. (2013). Accounting narratives and IM. In The Routledge companion to accounting communication (pp. 123–146). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brocke, J. V., Simons, A., Niehaves, B., Niehaves, B., Riemer, K., Plattfaut, R., & Cleven, A. (2009, June 7–10). Reconstructing the giant: On the importance of rigour in documenting the literature search process. ECIS 2009 Proceedings (pp. 161–175), Verona, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Busenbark, J. R., Lange, D., & Certo, S. T. (2017). Foreshadowing as IM: Illuminating the path for security analysts. Strategic Management Journal, 38(12), 2486–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callagher, L., & Garnevska, E. (2023). Multistakeholder IM tactics and sustainable development intentions in agri-food co-operatives. Journal of Management & Organization, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, Z., & Cai, R. (2013). ‘IM’ in Chinese corporations: A study of chairperson’s statements from the most and least profitable Chinese companies. Asia Pacific Business Review, 19(4), 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, Z., & Cai, R. (2014). Preference in presentation or IM: A comparison study between chairmen’s statements of the most and least profitable Australian companies. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 8(3), 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channel, J. (2000). Vague language. Shanghai Foreign Language Teaching Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. J., Song, P., & Loi, F. L. (2024). Strategic forward-looking nonearnings disclosure and overinvestment. The British Accounting Review, 56(6), 101431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, C., Mohamed, W., & Brahmbhatt, Y. (2023). Using FinBERT as a refined approach to measuring IM in corporate reports during a crisis. Communicare: Journal for Communication Sciences in Southern Africa, 42(1), 64–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chim-Miki, A. F., Fernandes, R. L. C., & Monticelli, J. M. (2024). Rethinking cluster under coopetition strategy: An integrative literature review and research agenda. Management Review Quarterly, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C. H., Michelon, G., & Patten, D. M. (2012). IM in sustainability reports: An empirical investigation of the use of graphs. Accounting and the Public Interest, 12(1), 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W. R., Clark, L. A., Raffo, D. M., & Williams, R. I. (2021). Extending Fisch and Block’s (2018) tips for a systematic review in management and business literature. Management Review Quarterly, 71, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clatworthy, M., & Jones, M. J. (2001). The effect of thematic structure on the variability of annual report readability. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 14(3), 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clatworthy, M., & Jones, M. J. (2003). Financial reporting of good news and bad news: Evidence from accounting narratives. Accounting and Business Research, 33(3), 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clatworthy, M. A., & Jones, M. J. (2006). Differential patterns of textual characteristics and company performance in the chairman’s statement. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 19(4), 493–511. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, P., Quinn, M., & Moreno, A. (2019). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: A longitudinal content analysis of corporate disclosures. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 10(2), 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C., Booth, A., Varley-Campbell, J., Britten, N., & Garside, R. (2018). Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: A literature review of guidance and supporting studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, S., & Slack, R. (2015). Reporting practice, IM and company performance: A longitudinal and comparative analysis of water leakage disclosure. Accounting and Business Research, 45(6–7), 801–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtis, J. K. (1998). Annual report readability variability: Tests of the obfuscation hypothesis. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 11(4), 459–472. [Google Scholar]

- Courtis, J. K. (2004). Corporate report obfuscation: Artefact or phenomenon? The British Accounting Review, 36(3), 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtis, J. K., & Hassan, S. (2002). Reading ease of bilingual annual reports. The Journal of Business Communication, 39(4), 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, R., Mortensen, T., & Iyer, S. (2013). Exploring top management language for signals of possible deception: The words of Satyam’s chair Ramalinga Raju. Journal of Business Ethics, 113, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cram, W. A., Templier, M., & Paré, G. (2020). (Re) considering the concept of literature review reproducibility. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 21(5), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, J. (2002). Communication and antithesis in corporate annual reports: A research note. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15(4), 594–608. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, J. (2008). Rhetoric, repetition, reporting and the “dot.com” era: Words, pictures, intangibles. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 21(6), 791–826. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, J. (2010). [In] visible [in] tangibles: Visual portraits of the business élite. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(2), 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, J. (2011). Paratextual framing of the annual report: Liminal literary conventions and visual devices. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 22(2), 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, E. B., Korzilius, H., Nickerson, C., & Gerritsen, M. (2006). A corpus analysis of text themes and photographic themes in managerial forewords of Dutch-English and British annual general reports. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 49(3), 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhludhlu, N., Phesa, M., & Sibanda, M. (2022). IM during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative analysis of the CS by JSE-listed profitable and least profitable companies. Journal of Accounting and Finance in Emerging Economies, 8(4), 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Northwood, G. (2015, July 2–3). A comparative linguistic analysis of statements by the chairman and chief executive officer (CEO) in BP plc’s published annual report of 2010. British Accounting & Finance Association Financial Reporting and Business Communication, Nineteenth Annual Conference, Bristol, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Doupnik, T. S., & Riccio, E. L. (2006). The influence of conservatism and secrecy on the interpretation of verbal probability expressions in the Anglo and Latin cultural areas. The International Journal of Accounting, 41(3), 237–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Text analysis for social research. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fisch, C., & Block, J. (2018). Six tips for your (systematic) literature review in business and management research. Management Review Quarterly, 68, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R., van Staden, C., & Richards, G. (2019, January 3–5). Tone and the accounting narrative. Hawaii Accounting Research Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Genette, G. (1997). Paratexts. Thresholds of interpretation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gimbar, C., Hansen, B., & Ozlanski, M. E. (2016). Early evidence on the effects of critical audit matters on auditor liability. Current Issues in Auditing, 10(1), A24–A33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitahi, J., Memba, F., & Nasieku, T. (2018). Relationship between the chairman’s statement and the value relevance of annual reports for listed banks in Kenya. Scientific Research Journal, VI(I), 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Guillamon-Saorin, E., Isidro, H., & Marques, A. (2017). IM and non-GAAP disclosure in earnings announcements. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 44(3–4), 448–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillamon-Saorin, E., & Sousa, C. M. (2010). Press release disclosures in Spain and the UK. International Business Review, 19(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Ponce, H., Chamizo González, J., & Al-Mohareb, M. (2024). The moderating effect of corporate governance on readability of the chairman’s statement: An analysis of Jordanian listed companies. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1994). An introduction to functional grammar (2nd ed.). Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, E. G., & Schaltegger, S. (2016). The sustainability balanced scorecard: A systematic review of architectures. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(2), 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herenia, G. P., Julián, C. G., & Al-mohareb, M. M. A. (2024). Does corporate governance influence readability of the report by the chairman of the board of directors? The case of Jordanian listed companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(4), 3535–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebl, M. R. (2023). Sample selection in systematic literature reviews of management research. Organizational Research Methods, 26(2), 229–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D., & Wang, Y. (2020). A CGA-based study on translation characteristics of chairman speeches in company annual reports. Journal of Literature and Art Studies, 10(2), 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, E., & Bucior, G. (2020). IM in financial reporting: Evidence on management commentary. IBIMA Business Review, 2020, 693684. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. J. (1988). A longitudinal study of the readability of the chairman’s narratives in the corporate reports of a UK company. Accounting and Business Research, 18(72), 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M. J., Melis, A., Gaia, S., & Aresu, S. (2020). IM and retrospective sense-making in corporate annual reports: Banks’ graphical reporting during the global financial crisis. International Journal of Business Communication, 57(4), 474–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugnandan, S., & Willows, G. D. (2022). “It’s a long story …”—IM in South African corporate reporting. Accounting Research Journal, 35(5), 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejeune, P. (1975). Le pacte autobiographique. Le Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Leventis, S., & Weetman, P. (2004). IM: Dual language reporting and voluntary disclosure. Accounting Forum, 28(3), 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboub, R., Mostapha, N., & Hegazy, W. (2016). IM in chairmen’s letters: An empirical study of banks’ annual reports in MENA region. Corporate Board: Role, Duties, and Composition, 12(3), 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Man, N. I., Abdullah, Z., Hasan, N. A. M., & Tamam, E. (2019). Chairman’s statement of a Malaysian public university: A critical discourse analysis. International Journal of Accounting, 4(19), 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mankayi, S., Matenda, F. R., & Sibanda, M. (2023). An analysis of the readability of the chairman’s statement in South Africa. Risks, 11(3), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matenda, F. R., Sibanda, M., Chikodza, E., & Gumbo, V. (2021). Bankruptcy prediction for private firms in developing economies: A scoping review and guidance for future research. Management Review Quarterly, 72, 927–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matenda, F. R., Sibanda, M., Nomlala, B. C., & Gumede, Z. H. (2023). South African business rescue regime: Systematic review highlighting shortcomings, recommendations and avenues for future research. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 12(2), 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melloni, G., Stacchezzini, R., & Lai, A. (2016). The tone of business model disclosure: An IM analysis of the integrated reports. Journal of Management and Governance, 20(2), 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkl-Davies, D. M., Brennan, N., & McLeay, S. (2005, May 18–20). A new methodology to measure IM-A linguistic approach to reading difficulty. 28th Annual Congress of the European Accounting Association, Göteborg, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Merkl-Davies, D. M., & Brennan, N. M. (2007). Discretionary disclosure strategies in corporate narratives: Incremental information or IM? Journal of Accounting Literature, 27, 116–196. [Google Scholar]

- Merkl-Davies, D. M., Brennan, N. M., & McLeay, S. J. (2011). IM and retrospective sense-making in corporate narratives: A social psychology perspective. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 24(3), 315–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkl-Davies, D. M., & Koller, V. (2012). ‘Metaphoring’people out of this world: A critical discourse analysis of a chairman’s statement of a UK defence firm. Accounting Forum, 36(3), 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M. Z., Chatterjee, B., & Rahaman, A. S. (2009). Culture and corporate voluntary reporting: A comparative exploration of the chairperson’s report in India and New Zealand. Managerial Auditing Journal, 24(7), 639–667. [Google Scholar]

- Mlawu, L., Matenda, F. R., & Sibanda, M. (2023). Linking financial performance with CEO statements: Testing IM theory. Risks, 11(3), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmako, N. (2016). The chairperson’s statement: Understanding prioritisation of discretionary disclosures by Johannesburg Security Exchange listed companies. Journal of Contemporary Management, 13(1), 385–408. [Google Scholar]

- Moola, M. (2016). An exploratory study into IM practices of chairman’s statements in South African annual reports [Ph.D. thesis, School of Accountancy, Faculty of Commerce, Law and Management, University of the Witwatersrand]. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, A., & Jones, M. J. (2022). IM in corporate annual reports during the global financial crisis. European Management Journal, 40(4), 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A., Jones, M. J., & Quinn, M. (2019). A longitudinal study of the textual characteristics in the chairman’s statements of Guinness: An IM perspective. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(6), 1714–1741. [Google Scholar]

- Moritz, A., Block, J. H., & Morina, F. (2024). Entrepreneurship in post-conflict countries: A literature review. Review of Managerial Science, 18, 3025–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, G. F., Arendse-Fourie, S. L., & Ontong, J. M. (2022). The association between optimism and future performance: Evidence of IM from chief executive officer and chairperson letters. South African Journal of Business Management, 53(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, A. (2009). A guide to systematic literature reviews. Surgery, 27(9), 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J., Azevedo, G., & Borges, F. (2016). IM and self-presentation dissimulation in Portuguese chairman’s statements. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 21(3), 388–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, D. L., & Peachey, J. W. (2013). A systematic literature review of servant leadership theory in organizational contexts. Journal of Business Ethics, 113(3), 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phesa, M., Khumalo, Q. P., & Sibanda, M. (2021). IM examination in chairpersons’ statements in the top 40 JSE listed companies. In Mbali conference 2021 proceedings. University of Zululand. [Google Scholar]

- Phesa, M., & Sibanda, M. (2022). A manifestation of IM in corporate reporting in JSE top 40 listed companies. Journal of Business and Social Review in Emerging Economies, 8(4), 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phesa, M., & Sibanda, M. (2023). IM in voluntary narrative disclosure through length and tone, stakeholder theory lens. Journal of Accounting and Finance in Emerging Economies, 9(3), 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phesa, M., Sibanda, M., & Gumede, Z. (2024). Assuring the CSin the integrated report: An auditing framework to curb the use of IM in corporate reporting. International Journal of Research in Business & Social Science, 13(5), 663–683. [Google Scholar]

- Phesa, M., Sibanda, M., & Gumede, Z. H. (2023). JSE delisted companies’ use of IM practices in the chairman’s statement and audit committee report preceding delisting from the 2016–2021 period. International Journal of Environmental, Sustainability, and Social Science, 4(4), 1162–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkina, L., & Sri Ramalu, S. (2024). Determinants and trends of executive coaching effectiveness in post-pandemic era: A critical systematic literature review analysis. Management Review Quarterly, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A. A., Hamdan, M. D., & Ibrahim, M. A. (2014). The use of graphs in Malaysian companies’ corporate reports: A longitudinal study. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 164, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, S. J. S., & Kawshalya, M. D. P. (2022). Differential patterns of textual characteristics in the chairman’s statement and company performance: Evidence from Sri Lanka. International Journal of Accountancy, 2(1), 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseberry, R. L. (1995). A texture index: Measuring texture in discourse. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 5(2), 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salancik, G. R., & Meindl, J. R. (1984). Corporate attributions as strategic illusions of management control. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29(2), 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassmannshausen, S. P., & Volkmann, C. (2018). The scientometrics of social entrepreneurship and its establishment as an academic field. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(2), 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, T., & Walker, M. (2010). Bias in the tone of forward-looking narratives. Accounting and Business Research, 40(4), 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, R. W. (2007). Appraising the quality of systematic reviews. Focus, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Segotso, T., Mvunabandi, J. D., & Phesa, M. (2024). A Systematic Literature Review of the Challenges of Adopting and Implementing IFRS for SMEs in South Africa. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 14(5), 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S., Varachia, Z., & Myeza, L. (2024). Integrated reports of IM techniques of the South African state-owned enterprises. Journal of Public Administration, 59(1), 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P., & Pecorari, D. (2013). Types of intertextuality in chairman’s statements. Nordic Journal of English Studies, 12(1), 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjovall, A. M., & Talk, A. C. (2004). From actions to impressions: Cognitive attribution theory and the formation of corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 7(3), 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skare, R. (2021). The paratext of digital documents. Journal of Documentation, 77(2), 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M., Dong, Y., & Ren, Y. (2011). The predictive ability of corporate narrative disclosures: Australian evidence. Asian Review of Accounting, 19(2), 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M., Jamil, A., Chik Johari, Y., & Ahmar Ahmad, S. (2006). The chairman’s statement in Malaysian companies: A test of the obfuscation hypothesis. Asian Review of Accounting, 14(1/2), 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M., & Taffler, R. (1992a). The chairman’s statement and corporate financial performance. Accounting & Finance, 32(2), 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M., & Taffler, R. (1992b). Readability and understandability: Different measures of the textual complexity of accounting narrative. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 5(4), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M., & Taffler, R. J. (2000). The chairman’s statement—A content analysis of discretionary narrative disclosures. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 13(5), 624–647. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stainbank, L., & Peebles, C. (2006). The usefulness of corporate annual reports in South Africa: Perceptions of preparers and users. Meditari: Research Journal of the School of Accounting Sciences, 14(1), 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, P., & Stanton, J. (2002). Corporate annual reports: Research perspectives used. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15(4), 478–500. [Google Scholar]

- Stenbacka, C. (2001). Qualitative research requires quality concepts of its own. Management Decision, 39(7), 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, C., Harr, M. D., & Pieper, T. M. (2024). Analyzing digital communication: A comprehensive literature review. Management Review Quarterly, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydserff, R., & Weetman, P. (1999). A texture index for evaluating accounting narratives: An alternative to readability formulae. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 12(4), 459–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydserff, R., & Weetman, P. (2002). Developments in content analysis: A transitivity index and DICTION scores. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15(4), 523–545. [Google Scholar]

- Talha, M., & Salim, A. S. A. (2011). Chairman statement characteristics and firms performance: A study of Malaysian construction companies. International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting, 3(2), 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templier, M., & Paré, G. (2018). Transparency in literature reviews: An assessment of reporting practices across review types and genres in top IS journals. European Journal of Information Systems, 27(5), 503–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totowa, J., & Mokoaleli-Mokoteli, T. (2021). Chairman’s letter, IM and governance mechanisms: A case of South African listed firms. African Finance Journal, 23(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregidga, H., Milne, M., & Lehman, G. (2012). Analyzing the quality, meaning and accountability of organizational reporting and communication. Accounting Forum, 36(3), 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varachia, Z., & Yasseen, Y. (2020). The use of graphs as an IM tool in the annual integrated reports of South African listed entities. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences, 13(1), a548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivian, Y. C. L., & Mei, C. C. Y. (2022). Move structuring and metadiscourse strategies in public listed companies’ chairperson statements. LSP International Journal, 9(1), 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, R. (2018). Persuasion in business documents: Strategies for reporting positively on negative phenomena. Ostrava Journal of English Philology, 10(1), 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- vom Brocke, J., Simons, A., Riemer, K., Niehaves, B., Plattfaut, R., & Cleven, A. (2015). Standing on the shoulders of giants: Challenges and recommendations of literature search in information systems research. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 37, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Li, L., & Cao, J. (2012). Lexical features in corporate annual reports: A corpus-based study. European Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 1(9), 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. (2016). Literature review on the IM in corporate information disclosure. Modern Economy, 7(6), 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K. E. (1995). The social psychology of organizing. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, L., & Kanbach, D. (2022). Toward an integrated framework of corporate venturing for organizational ambidexterity as a dynamic capability. Management Review Quarterly, 72(4), 1129–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z. (1999). Corporate disclosures made by Chinese listed companies. The International Journal of Accounting, 34(3), 349–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasseen, Y., Mohamed, W., & Moola-Yasseen, M. (2019). The use of IM practices in the chairman’s statements in South African annual reports: An agency theory perspective. Communicare: Journal for Communication Sciences in Southern Africa, 38(1), 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yasseen, Y., Moola-Yasseen, M., & Padia, N. (2017). A preliminary study into IM practices in chairman’s statements in South African annual reports: An attribution theory perspective. Communicare: Journal for Communication Sciences in Southern Africa, 36(1), 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, V. C. L., & Cheong, C. Y. M. (2022). Socio-cognitive and Professional Practice Perspectives on Chairperson Statements. Journal of Modern Languages, 32(1), 19–36. [Google Scholar]

| Author(s) (Publication Year) | Title of the Article | Name of the Journal/Conference Proceedings | Quality of the Journal (Scopus) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jones (1988) | A longitudinal study of the readability of the chairman’s narratives in the corporate reports of a UK company | Accounting and Business Research | Q2 | Corporate reports are challenging to read and have become more challenging to read over time. |

| Smith and Taffler (1992a) | The chairman’s statement and corporate financial performance | Accounting and Finance | Q1 | There is a correlation between readability of the chairperson’s narrative and financial performance and distinct performance measures, whilst poor readability is related to poor financial performance. |

| Smith and Taffler (1992b) | Readability and understandability: different measures of the textual complexity of accounting narrative | Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal | Q1 | Understandability and readability are dissimilar notions. Standards designers must focus on “understandability” as a wanted feature of accounting disclosures. |

| Courtis (1998) | Annual report readability variability: tests of the obfuscation hypothesis | Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal | Q1 | Discernible reading-ease patterns exist. Obfuscation is associated with firms with high financial press coverage. |

| Smith and Taffler (2000) | The CS—a content analysis of discretionary narrative disclosures | Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal | Q1 | CSs are closely related to financial performance, supporting the claim that such unaudited disclosures encompass significant information. |

| Clatworthy and Jones (2001) | The effect of thematic structure on the variability of annual report readability | Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal | Q1 | The CS’s introduction is easier to read than other portions of the CS. The CS’s thematic structure is an essential determinant of annual report readability variability. |

| Courtis and Hassan (2002) | Reading ease of bilingual annual reports | The Journal of Business Communication | N/A | Indigenous language versions are more straightforward to read than English-written ones. Dissimilar language versions produce dissimilar reading behaviour and can have resource distribution decision-making inferences. |

| Davison (2002) | Communication and antithesis in corporate annual reports: a research note | Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal | Q1 | The visual and textual material offers a wider context by merging instants from world and corporate history with the bulletin of corporate developments and recent matters. |

| Sydserff and Weetman (2002) | Developments in content analysis: a transitivity index and DICTION scores | Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal | Q1 | Differentiation results between poor performers and good performers are mixed. There is evidence of IM. |

| Courtis (2004) | Corporate report obfuscation: artefact or phenomenon? | The British Accounting Review | N/A | Reading is complex, and variability is pervasive. |

| Clatworthy and Jones (2003) | Financial reporting of good news and bad news: evidence from accounting narratives | Accounting and Business Research | Q2 | Firms underscore the positive characteristics of their performance. Firms seize credit for good news themselves, condemning the external atmosphere for bad news. |

| Beynon et al. (2004) | The prediction of profitability using accounting narratives: a variable-precision rough set approach | Intelligent Systems in Accounting, Finance and Management: International Journal | Q2 | Most informative is the percentage of good news words, lousy news words, and positive keywords. |

| Clatworthy and Jones (2006) | Differential patterns of textual characteristics and company performance in the chairperson’s statement | Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal | Q1 | The CS is exposed to IM tactics as managers’ inclination to relate themselves to the firm financial results is related to the firm’s financial performance. Firms that are not profitable focus more on the future instead of past performance. |

| de Groot et al. (2006) | A corpus analysis of text themes and photographic themes in managerial forewords of Dutch-English and British annual general reports | IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication | N/A | Substantial thematic disparities exist between the Dutch–English CEO’s statements, the British CEO’s statements, and the British CS. These differences may be accredited to communicative and historical arrangements and recent affairs in a specific business environment. |

| Smith et al. (2006) | The chairman’s statement in Malaysian companies: a test of the obfuscation hypothesis | Asian Review of Accounting | Q2 | There are substantial associations between financial performance and corporate language. |

| Merkl-Davies and Brennan (2007) | Discretionary disclosure strategies in corporate narratives: incremental information or IM? | Journal of Accounting Literature | Q3 | Firm narrative documents are viewed as conduits for manipulating the verdicts and insights of external parties concerning corporate prospects and performance. |

| Beattie et al. (2008) | Investigating presentational change in UK annual reports: a longitudinal perspective | The Journal of Business Communication | N/A | IM via graphical measurement distortion, selectivity, and manipulation of the length of time series graphs is widespread. |

| Davison (2008) | Rhetoric, repetition, reporting and the “dot.com” era: words, pictures, intangibles | Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal | Q1 | Repetition highlights BT plc’s intangible assets; less intentionally, repetition indicates BT plc’s corporate uniqueness and its partaking in the “dot.com” era. |

| Bhana (2009) | The chairperson’s statements and annual reports: are they reporting the same company performance to investors? | Investment Analysts Journal | Q3 | Firms highpoint the positive facets of their performance. Companies seize credit for good news while condemning the external atmosphere for bad news. |

| Mir et al. (2009) | Culture and corporate voluntary reporting: a comparative exploration of the chairperson’s report in India and New Zealand | Managerial Auditing Journal | Q1 | Conflicting with suggestions premised on Hofstede’s cultural framework, Indian firms offer more disclosure in their chairperson’s reports than New Zealand firms. |

| Davison (2011) | Paratextual framing of the annual report: liminal literary conventions and visual devices | Critical Perspectives on Accounting | Q1 | Narrative and visual components of the annual report (physical format, names, authorship, titles, epigraphs, prefaces (introduction/CS) and intertitles) frame the reception of the text. |

| Merkl-Davies et al. (2011) | IM and retrospective sense-making in corporate narratives: a social psychology perspective | Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal | Q1 | Negative firm results stimulate managers to participate in retrospective sense-making instead of giving a picture of firm performance conflicting with the opinion. |

| Smith et al. (2011) | The predictive ability of corporate narrative disclosures: Australian evidence | Asian Review of Accounting | Q2 | Word-based variables premised on discretionary disclosures are considerably associated with corporate performance. |

| Talha and Salim (2011) | Chairman statement characteristics and firms performance: a study of Malaysian construction companies | International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting | Q3 | No substantial differences between profitable and unprofitable firms besides the fact that profitable firms have a habit of presenting more graphs and pictures in the CS segment while presenting their bottom-line performance. |

| Bayerlein and Davidson (2012) | The influence of connotation on readability and obfuscation in Australian chairman addresses | Managerial Auditing Journal | Q1 | Mid-segment of the CSs was substantially more challenging to read than the first and last segments. |

| Merkl-Davies and Koller (2012) | ‘Metaphoring’ people out of this world: a critical discourse analysis of a chairman’s statement of a UK defence firm | Accounting Forum | Q1 | Impersonalisation and evaluation are intentionally utilised to direct organisational audiences’ interpretations of financial success as well as to legitimise and normalise violence and devastation by abstracting and sanitising its representation. |

| H. Wang et al. (2012) | Lexical features in corporate annual reports: a corpus-based study | European Journal of Business and Social Sciences | N/A | Vocabulary of the CSs is the richest, whereas that of the auditor’s report is not rich. In auditor’s and corporate social responsibility reports, words are lengthier and more sophisticated than those in financial and CSs. |

| Cen and Cai (2013) | ‘IM’ in Chinese corporations: a study of chairperson‘s statements from the most and least profitable Chinese companies | Asia Pacific Business Review | Q2 | IM drives and inspires CSs in the Chinese environment in several ways. |

| Craig et al. (2013) | Exploring top management language for signals of possible deception: the words of Satyam’s chair Ramalinga Raju | Journal of Business Ethics | Q1 | Raju’s selection of words was transformed strikingly in his five yearly report communications before Satyam’s failure as the degree and effect of his financial misstatements amplified. |

| Shaw and Pecorari (2013) | Types of intertextuality in CSs | Nordic Journal of English Studies | Q1 | Production format for the texts shows signs of templates and repetition. They are frequent and appear in all thematic units. |

| Athanasakou and Hussainey (2014) | The perceived credibility of forward-looking performance disclosures | Accounting and Business Research | Q2 | Firms release more forward-looking performance disclosures (FLPDs) when soliciting debt or transmitting bad news in the financial statements. |

| Cen and Cai (2014) | Preference in presentation or IM: a comparison study between chairmen’s statements of the most and least profitable Australian companies | Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance | Q2 | Chairperson’s letters from profitable and non-profitable Australian firms show diverse presentational preferences. |

| Cooper and Slack (2015) | Reporting practice, IM and company performance: a longitudinal and comparative analysis of water leakage disclosure | Accounting and Business Research | Q2 | The nature, level, and appearance of a sewerage and water firm’s leakage disclosures vary distinctly depending on their performance against the Water Services Regulation Authority’s target. |

| D’Northwood (2015) | A comparative linguistic analysis of statements by the chairperson and chief executive officer (CEO) in BP plc’s published annual report of 2010 | British Accounting and Finance Association Financial Reporting and Business Communication, Nineteenth Annual Conference | N/A | Readers’ observations are moulded by the CSs and CEO statements of BP plc in the firm’s 2010 annual report. However, resemblances and disparities are evident in how this positioning is engineered. Resemblances and disparities are not restricted to BP plc. |

| Oliveira et al. (2016) | IM and self-presentation dissimulation in Portuguese chairmen’s statements | Corporate Communications | Q2 | Implementation of IM strategies is unaffected by organisational results. Critical elements in describing them are consumer proximity and public visibility. |

| Mahboub et al. (2016) | IM in chairmen’s letters: an empirical study of banks’ annual reports in MENA region | Corporate Board: Role, Duties and Composition | N/A | IM strategies in the chairperson’s letters: reading-ease manipulation, performance comparisons, structural and visual manipulation, and performance attribution. Annual report narrative is complicated to read. Yardsticks that depict present bank performance in the best imaginable light are chosen. |

| Mmako (2016) | The chairperson’s statement: understanding prioritisation of discretionary disclosures by Johannesburg Security Exchange listed companies | Journal of Contemporary Management | Q1 | Significant variances between the CSs of poor-performing and high-performing firms were the weight put on issues like devotion to corporate governance. High-performing firms could better deal with most content essentials of an integrated report in their CS and the proactive and reactive reactions to the firms’ performance. |

| Yasseen et al. (2017) | A preliminary study into IM practices in chairperson’s statements in South African annual reports: an attribution theory perspective | Communicare: Journal for Communication Studies in Africa | N/A | IM exists in the CSs of the JSE main board listed firms. “Extremely unprofitable” firms are less expected to use IM. |

| Gitahi et al. (2018) | Relationship between the CS and the value relevance of annual reports for listed banks in Kenya | Scientific Research Journal | N/A | The CS was positively and significantly connected to the value relevance of annual reports. |

| Vogel (2018) | Persuasion in business documents: strategies for reporting positively on negative phenomena | Ostrava Journal of English Philology | Q3 | Ten approaches have been recognised, fitting into two big clusters (i.e., facing problems vs. relativising problems). |

| Ahmed and Salat (2019) | A thematic analysis of chairman’s statement of the commercial banks of Bangladesh | Barishal University Journal (Part-3) | N/A | Banks highlight the positive facets of their performance while accusing the external environment of bad reports. Consequently, IM practices were apparent. |

| Cleary et al. (2019) | Socioemotional wealth in family firms: a longitudinal content analysis of corporate disclosures | Journal of Family Business Strategy | Q1 | CS does contain FIBER dimensions (“Family control and influence, Identification of family members with the firm, Binding social ties, Emotional attachment of family members, and Renewal of family bonds to the firm through dynastic succession”), and they do alter over time. |

| Fisher et al. (2019) | Tone and the accounting narrative | Hawaii Accounting Research Conference | N/A | Chairperson’s and corporate social responsibility opening letters display high optimism, positivity, and realism. Readability throughout all disclosure kinds was “very difficult”. |

| Man et al. (2019) | Chairman’s statement of a Malaysian public university: a critical discourse analysis | International Journal of Accounting, Finance and Business | N/A | Management strategically employs linguistic and semiotic strategies to meet several economic and political objectives and aims. |

| Moreno et al. (2019) | A longitudinal study of the textual characteristics in the chairman’s statements of Guinness: an IM perspective | Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal | Q1 | Guinness constantly employed qualitative textual features with a self-centred bias. Nevertheless, Guinness did not employ those with a more quantitative nature. |

| Yasseen et al. (2019) | The use of IM practices in the chairperson’s statements in South African annual reports: an agency theory perspective | Communicare: Journal for Communication Studies in Africa | N/A | Managers use IM strategies that are contingent on the firm’s performance. Readability variability was not implemented as a strategy to handle impressions. The CS was mainly challenging to understand. |

| Al-Sayani et al. (2020) | The influence of audit committee characteristics on IM in chairman statement: evidence from Malaysia | Cogent Business and Management | Q2 | Audit Committee (AC) independence is adversely related to the IM level measured, premised on quantitative and qualitative scores. AC meetings are positively related to the IM level, premised on qualitative scores. |

| Huang and Wang (2020) | A CGA-based study on translation characteristics of chairman speeches in company annual reports | Journal of Literature and Art Studies | N/A | Chairperson speeches comprise particular move structures and explicit communication aims, with industry atmosphere and self-interest contribution strongly affecting the rhetorical selections and wording of the chairperson speeches, and this can be elucidated as follows: the interactivity generates an interdiscursive association between business genre society and industry routine. |

| Phesa et al. (2021) | IM examination in chairpersons’ statements in the top 40 JSE-listed companies | Mbali Conference 2021 Proceedings | N/A | Top 40 JSE-listed firms participate in IM. Unprofitable firms implemented more personal references than profitable firms, while profitable firms implemented more positive sentiments than unprofitable firms. |

| Rosa and Kawshalya (2022) | Differential patterns of textual characteristics in the CS and company performance: evidence from Sri Lanka | International Journal of Accountancy | N/A | Corporation’s performance substantially influences the content of the CS. |

| Totowa and Mokoaleli-Mokoteli (2021) | Chairman’s letter, IM and governance mechanisms: a case of South African listed firms | African Finance Journal | Q4 | Managers employ mainly optimistic language in the chairperson’s letter to generate an impression regarding their corporates. This optimistic language is less employed by poorly performing corporates. |

| Dhludhlu et al. (2022) | IM during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparative analysis of the CS by JSE-listed profitable and least profitable companies | Journal of Accounting and Finance in Emerging Economies | N/A | Least profitable and profitable top 100 JSE-listed firms employed IM throughout the pandemic. Firms employed passive voice and personal, future, and quantitative references in the CS. No substantial differences in quantitative references, readability, passive voice, length, personal references, and future references between these two groups of firms. |

| Moreno and Jones (2022) | IM in corporate annual reports during the global financial crisis | European Management Journal | Q1 | No proof exists that IM was used during the global financial crisis. Businesses strived not to employ obvious IM and, to a certain degree, stated how a crisis has affected their performance. Businesses used optimistic attributions, praise benchmarks, and improvement techniques. |

| Nel et al. (2022) | The association between optimism and future performance: evidence of IM from chief executive officer and chairperson letters | South African Journal of Business Management | Q3 | CSs were more optimistic than CEO statements. There was evidence of IM in both CSs. |

| Phesa and Sibanda (2022) | Manifestation of IM in corporate reporting in JSE top 40 listed companies | Journal of Business and Social Review in Emerging Economies | N/A | Profitable and unprofitable firms employed self-attribution bias. No substantial differences exist even though profitable firms employ more self-attribution than unprofitable firms. |

| Vivian and Mei (2022) | Move structuring and metadiscourse strategies in public listed companies’ chairperson statements | LSP International Journal | N/A | Schematic structuring of CSs is dissimilar from the prior structuring models with four novel moves. Variances were discovered in the distribution of interactive and interactional markers throughout the moves. |

| Yee and Cheong (2022) | Socio-cognitive and professional practice perspectives on chairperson statements | Journal of Modern Languages | N/A | Three informational moves are implemented to help investment verdicts, whereas seven non-informational moves are envisioned to promote a good image and goodwill and to guarantee adherence to prerequisites. CSs are promotional, interdiscursively informational, and public relational. |

| Al-Sayani and Al-Matari (2023) | Corporate governance characteristics and IM in financial statements. A further analysis. Malaysian evidence | Cogent Social Sciences | Q2 | Board of directors characteristics have a substantial relationship with IM. Features of board chairperson, audit committee, and ownership structure significantly influence IM. The effectiveness of the board of directors and chairperson has a substantial effect on IM. |

| Al Lawati et al. (2023) | Forward-looking disclosure tone in the chairman’s statement: obfuscation or truthful explanations | International Journal of Accounting and Information Management | Q1 | Good-performing corporates reveal more good news, whereas poor ones reveal more bad news. |

| Callagher and Garnevska (2023) | Multistakeholder IM tactics and sustainable development intentions in agri-food co-operatives | Journal of Management and Organization | Q1 | Three themes were revealed: (i) a commonness of impression statements that offer accounts or make justifications concerning the People and Profit themes, (ii) escalating impressions regarding affairs for the Planet ensuing Sustainable Development Goals endorsement, and (iii) escalating impressions of integrative conceptions by several co-operatives. |

| Mankayi et al. (2023) | An analysis of the readability of the CS in South Africa | Risks | Q2 | It is difficult to read the CSs for the chosen firms. |

| Phesa and Sibanda (2023) | IM in voluntary narrative disclosure through length and tone, stakeholder theory lens | Journal of Accounting and Finance in Emerging Economies | N/A | Profitable and unprofitable corporates employ IM via the CS length and positive tone. |

| Cherry et al. (2023) | Using FinBERT as a refined approach to measuring IM in corporate reports during a crisis | Communicare: Journal for Communication Sciences in Southern Africa | N/A | No general configuration of communication appeared in the CSs. |

| Phesa et al. (2023) | JSE delisted companies’ use of IM practices in the chairman’s statement and audit committee report preceding delisting from the 2016–2021 period | International Journal of Environmental, Sustainability, and Social Science | N/A | Delisted firms employed IM prior to delisting. |

| Gutiérrez Ponce et al. (2024) | The moderating effect of corporate governance on the readability of the chairman’s statement: an analysis of Jordanian listed companies | Environment, Development and Sustainability | Q1 | Corporate governance substantially moderates the readability of the CS and the corporation’s performance. There is an association between the CS readability and features of the board like directors’ accounting know-how, independence, and board’s ownership concentration. |

| Herenia et al. (2024) | Does corporate governance influence the readability of the report by the chairman of the board of directors? The case of Jordanian listed companies | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | Q1 | Corporate governance moderates the president’s statement readability and the corporation’s performance. There is a connection between the CS readability and the accounting experience of directors. |

| Shaikh et al. (2024) | Integrated reports of IM techniques of the South African state-owned enterprises | Journal of Public Administration | Q2 | State-owned enterprises implement IM tactics in their integrated reports. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Phesa, M.; Sibanda, M.; Matenda, F.R.; Gumede, Z. Impression Management Tactics in the Chairperson’s Statement: A Systematic Literature Review and Avenues for Future Research. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050270

Phesa M, Sibanda M, Matenda FR, Gumede Z. Impression Management Tactics in the Chairperson’s Statement: A Systematic Literature Review and Avenues for Future Research. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(5):270. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050270

Chicago/Turabian StylePhesa, Masibulele, Mabutho Sibanda, Frank Ranganai Matenda, and Zamanguni Gumede. 2025. "Impression Management Tactics in the Chairperson’s Statement: A Systematic Literature Review and Avenues for Future Research" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 5: 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050270

APA StylePhesa, M., Sibanda, M., Matenda, F. R., & Gumede, Z. (2025). Impression Management Tactics in the Chairperson’s Statement: A Systematic Literature Review and Avenues for Future Research. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(5), 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050270