An Interdisciplinary Study: Deferred Tax Implications of Lay-By Agreements for Financial Planning and Decision Making

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Background

(2A) In the case of a lay-by agreement as contemplated in section 62 of the Consumer Protection Act, 2008 (Act No. 68 of 2008), the Commissioner may make an allowance in respect of all amounts which are deemed to have accrued under such agreement but which have not been received by the end of the taxpayer’s year of assessment.

- SARS’s view (Interpretation 1);

- Haupts’ view (Interpretation 2);

- Hassan and Van Heerden’s view (Interpretation 3).

1.2. Research Problem and Justification for the Study

1.3. Research Objective

- Sub-research question 1: What are the revenue recognition implications of lay-by agreements? and

- Sub-research question 2: What are the deferred tax implications following from the three tax interpretations?

1.4. Contribution of This Research

2. Materials and Methods

3. Literature Review

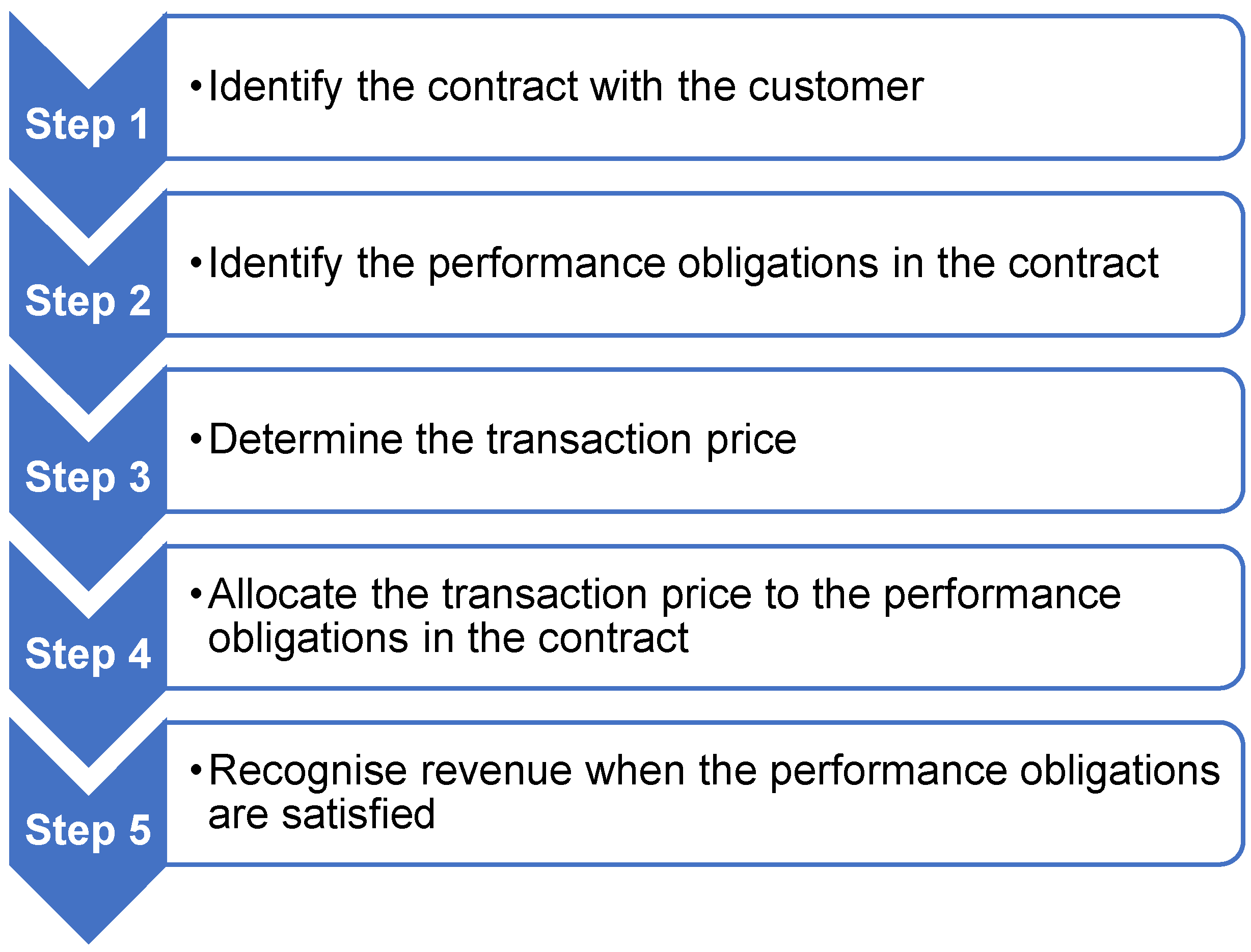

3.1. Accounting Implications for Revenue Recognition in Terms of IFRS 15

“Control of an asset refers to the ability to direct the use of, and obtain substantially all of the remaining benefits from, the asset. Control includes the ability to prevent other entities from directing the use of, and obtaining the benefits from, an asset.”

3.2. Deferred Tax Implications in Terms of IAS 12

“The tax base of an asset or liability is the amount attributed to that asset or liability for tax purposes.The tax base of an asset is the amount that will be deductible for tax purposes against any taxable economic benefits that will flow to an entity when it recovers the carrying amount of the asset. If those economic benefits will not be taxable, the tax base of the asset is equal to its carrying amount.The tax base of a liability is its carrying amount, less any amount that will be deductible for tax purposes in respect of that liability in future periods. In the case of revenue which is received in advance, the tax base of the resulting liability is its carrying amount, less any amount of the revenue that will not be taxable in future periods.”

“… taxable temporary differences, which are temporary differences that will result in taxable amounts in determining taxable profit (tax loss) of future periods when the carrying amount of the asset or liability is recovered or settled; ordeductible temporary differences, which are temporary differences that will result in amounts that are deductible in determining taxable profit (tax loss) of future periods when the carrying amount of the asset or liability is recovered or settled.”;

4. Results

4.1. The Revenue Recognition Implications of Lay-By Agreements

4.1.1. Identify the Contract with the Customer

- (a)

- each amount paid by the consumer to the supplier remains the property of the consumer, and is subject to section 65, until the goods have been delivered to the consumer; and

- (b)

- the particular goods remain at the risk of the supplier until the goods have been delivered to the consumer. [emphasis added]

4.1.2. Identify the Performance Obligations in the Contract

4.1.3. Determine the Transaction Price

4.1.4. Allocate the Transaction Price to the Performance Obligations in the Contract

4.1.5. Recognise Revenue When the Performance Obligations Are Satisfied

4.2. The Resulting Deferred Tax Implications

4.2.1. Deferred Tax Implications for Contract Liability

4.2.2. Deferred Tax Implications for Unearned Revenue

4.2.3. Deferred Tax Implications for Section 24 Allowance

4.2.4. Deferred Tax Implications for Inventory

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPA | Consumer Protection Act |

| EFRAG | European Financial Reporting Advisory Group |

| IASB | International Accounting Standards Board |

| IFRS | International Financial Reporting Standards |

| SARS | South African Revenue Services |

References

- Australian Taxation Office. (1995). Income tax: Lay-by sales (TR 95/7). Available online: https://www.ato.gov.au/law/view/document?locid=%27TXR/TR957/NAT/ATO%27&PiT=20010620000001#LawTimeLine (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Chynoweth, P. (2008). Legal research. In A. Knight, & L. Ruddock (Eds.), Advanced research methods in the built environment (pp. 28–38). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Coetsee, D. (2019). Policy research in accounting: A doctrinal research perspective. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences, 12(1), a405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst & Young. (2015). International GAAP. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- European Financial Reporting Advisory Group. (2011). Improving the financial reporting of income tax. Available online: https://www.efrag.org/sites/default/files/sites/webpublishing/SiteAssets/120127_Income_tax_DP_final.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Evans, E., Burritt, R., & Guthrie, J. (2011). Bridging the gap between academic accounting research and professional practice. The Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Görlitz, A., & Dobler, M. (2021). Financial accounting for deferred taxes: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Management Review Quarterly, 73, 113–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J., Raedy, J., & Shackelford, D. (2012). Research in accounting for income taxes. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 53(1–2), 412–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M., & Van Heerden, M. (2024). Section 24 amendment introduces additional uncertainty in interpretation, enforcement and tax compliance. In T. Moloi, & B. George (Eds.), Towards digitally transforming accounting and business processes, ICAB 2023 Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics (pp. 305–320). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, P., & Haupt, E. (2023). Notes on South African income tax. H&H Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, T., & Duncan, N. (2012). Defining and describing what we do: Doctrinal legal research. Deakin Law Review, 17(1), 83–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inanga, E. L., & Schneider, W. B. (2005). The failure of accounting research to improve practice: A problem of theory and lack of communication. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 16(3), 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2022a). Basis for conclusions on IFRS 15 revenue from contracts with customers. In IASB (Ed.), The annotated IFRS standards (Part C2, pp. B1229–B1446). The IFRS Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2022b). IAS 12 income taxes. In IASB (Ed.), The annotated IFRS standards (Part A2, pp. A1305–A1365). The IFRS Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2022c). IFRS 15 revenue from contracts with customers. In IASB (Ed.), The annotated IFRS standards (Part A1, pp. A885–A972). The IFRS Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Louw, H. (2022). Lay-by arrangements and debtors allowances. Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr. Available online: https://www.cliffedekkerhofmeyr.com/en/news/publications/2022/Practice/Tax/tax-and-exchange-control-alert-23-february-special-edition-2022-budget-speech-Lay-by-arrangements-and-debtors-allowances.html (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- McKerchar, M. (2010). Design and conduct of research in tax, law and accounting. Lawbook Co., Thomson Reuters (Professional) Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Mear, K., Bradbury, M., & Hooks, J. (2021). The ability of deferred tax to predict future tax. Accounting and Finance, 61, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napier, C., & Stadler, C. (2020). The real effects of a new accounting standard: The case of IFRS 15 revenue from contracts with customers. Accounting and Business Research, 50(5), 474–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Treasury. (2023a). Explanatory memorandum on the taxation laws amendment bill, 2022. Available online: https://www.sars.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/Legal/ExplMemo/Legal-LPrep-EM-2022-02-Explanatory-Memorandum-on-the-Taxation-Laws-Amendment-Bill-2022-16-January-2023.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- National Treasury. (2023b). Taxation laws amendment act, 2022. Available online: https://www.sars.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/Legal/AmendActs/LPrim-AA-2022-02-Taxation-Laws-Amendment-Act-20-of-2022-GG-47826-5-Jan-2023.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Nel, P. J. (2023). Manage your practice: Lay-by agreements and tax. SAICA. Available online: https://www.accountancysa.org.za/manage-your-practice-lay-by-agreements-and-tax/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Parker, L. D., & Guthrie, J. (2014). Assessing the directions of interdisciplinary accounting research. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 27(8), 1218–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepkor Holdings Limited. (2024). Pepkor holdings limited integrated report 2024. Available online: https://pepkor.co.za/wp-content/uploads/Pepkor-integrated-report-2024.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Purnamasari, D. (2019). How the effect of deferred tax expenses and tax planning on earnings management? International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research, 8(2), 78–83. Available online: https://www.ijstr.org/final-print/feb2019/How-The-Effect-Of-Deferred-Tax-Expenses-And-Tax-Planning-On-Earning-Management-.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- PwC. (2007). Measuring assets and liabilities—Investment professionals’ views. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/audit-services/corporate-reporting/assets/pdfs/measuring-asset-and-liabilities.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Republic of South Africa. (1962). (Act No. 58 of 1962) (as amended). Government Printer. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of South Africa. (2008). Consumer protection act (Act No. 68 of 2008). Government Printer. [Google Scholar]

- Saptono, P. B., & Khozen, I. (2021). Tax administration issues on revenue recognition after IFRS 15 adoption in Indonesia. Jurnal Borneo Administrator, 17(2), 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton-Green, B. (2009). The communication gap: Why doesn’t accounting research make a greater contribution to debates on accounting policy? Accounting in Europe, 7(2), 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Revenue Service. (2018). Interpretation note 48: Instalment credit agreements and debtors’ allowance. Available online: https://www.sars.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/Legal/Notes/LAPD-IntR-IN-2012-48-Instalment-Credit-Agreements-Debtors-Allowance.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Stack, E. (2019). Research methodology module: Legal research. Department of Accounting, Rhodes University. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, B. P., & Lowe, A. D. (2014). Practitioners are from Mars, academics are from Venus? An investigation of the research-practice gap in management accounting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 27(3), 394–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoecke, M. (2011). Legal doctrine: Which method(s) for what kind of discipline? In M. Van Hoecke (Ed.), Methodologies of legal research: Which kind of method for what kind of discipline? (pp. 1–18) Hart. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk, M., & Coetsee, D. (2020). The adequacy of IFRS 15 for revenue recognition in the construction industry. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences, 13(1), a474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, B. R., & Durden, C. H. (2015). Inducing structural change in academic accounting research. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 26, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Income Tax Implication | Interpretation 1 | Interpretation 2 | Interpretation 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tax position at year-end in respect of lay-by agreements | ZAR | ZAR | ZAR |

| Deemed accrual of sales proceeds, per section 24(1) of the Income Tax Act | 1,000,000 | 1,000,000 | 0 |

| Section 24(2A) debtors’ allowance (based on gross profit %, therefore ZAR 900,000 × 20%) | (180,000) | 0 | |

| Section 24(2A) debtors’ allowance (100% of the deemed accrual amount) | (1,000,000) | ||

| Purchases, deduction (ZAR 1,000,000 × 80% = ZAR 800,000) | (800,000) | (800,000) | (800,000) |

| Add: Closing stock, per section 22(1) | 0 * | 800,000 | 800,000 |

| Effect on taxable income of Company A | 20,000 | 0 | 0 |

| Interpretation 1 | Interpretation 2 | Interpretation 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deferred Tax Implications Using the Balance Sheet Method | ZAR | ZAR | ZAR |

| Deferred tax implications for contract liability (Section 4.2.1) | |||

| Carrying amount of the contract liability | ZAR 100,000 1 | ZAR 100,000 1 | ZAR 100,000 1 |

| Tax base | 0 2 | 0 2 | ZAR 100,000 3 |

| Deductible temporary difference | ZAR 100,000 | ZAR 100,000 | 0 |

| Deferred tax asset @ 27% | ZAR 27,000 | ZAR 27,000 | 0 |

| Deferred tax implications for unearned revenue (Section 4.2.2) | |||

| Carrying amount of unrecognised revenue | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tax base | ZAR 900,000 4 | ZAR 900,000 4 | 0 |

| Deductible temporary difference | ZAR 900,000 | ZAR 900,000 | 0 |

| Deferred tax asset @ 27% | ZAR 243,000 | ZAR 243,000 | 0 |

| Deferred tax implications for section 24 allowance (Section 4.2.3) | |||

| Carrying amount of the section 24 allowance | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tax base | ZAR 180,000 | ZAR 1,000,000 | 0 |

| Taxable temporary difference | ZAR 180,000 5 | ZAR 1,000,000 5 | 0 |

| Deferred tax liability @ 27% | (ZAR 48,600) | (ZAR 270,000) | 0 |

| Deferred tax implications for inventory (Section 4.2.4) | |||

| Carrying amount of inventory | ZAR 800,000 6 | ZAR 800,000 6 | ZAR 800,000 6 |

| Tax base | 0 7 | ZAR 800,000 8 | ZAR 800,000 8 |

| Taxable temporary difference | (ZAR 800,000) | 0 | 0 |

| Deferred tax liability @ 27% | (ZAR 216,000) | 0 | 0 |

| Total deferred tax asset recognised | ZAR 5400 | 0 | 0 |

| Interpretation 1 | Interpretation 2 | Interpretation 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deferred Tax Implications Using the Income Statement Method | ZAR | ZAR | ZAR |

| Accounting profit | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Add: Deemed accrual of sales proceeds, as per section 24(1) | 1,000,000 | 1,000,000 | 0 |

| Deduct: Section 24 allowance (ZAR 900,000 × 20%) | (180,000) | 0 | |

| Deduct: Section 24 allowance (100% of deemed accrual) | (1,000,000) | 0 | |

| Deduct: Purchases, deduction (ZAR 1,000,000 × 80% = R800,000) | (800,000) | (800,000) | (800,000) |

| Add: Closing stock (section 22(1)) | 0 | 800,000 | 800,000 |

| Total deductible temporary differences | 20,000 | ||

| Deferred tax asset @ 27% | ZAR 5400 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohammadali Haji, A.; Hassan, M.; van Heerden, M.; van Wyk, M. An Interdisciplinary Study: Deferred Tax Implications of Lay-By Agreements for Financial Planning and Decision Making. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050273

Mohammadali Haji A, Hassan M, van Heerden M, van Wyk M. An Interdisciplinary Study: Deferred Tax Implications of Lay-By Agreements for Financial Planning and Decision Making. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(5):273. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050273

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohammadali Haji, Ahmed, Muneer Hassan, Michelle van Heerden, and Milan van Wyk. 2025. "An Interdisciplinary Study: Deferred Tax Implications of Lay-By Agreements for Financial Planning and Decision Making" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 5: 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050273

APA StyleMohammadali Haji, A., Hassan, M., van Heerden, M., & van Wyk, M. (2025). An Interdisciplinary Study: Deferred Tax Implications of Lay-By Agreements for Financial Planning and Decision Making. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(5), 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050273