Abstract

Despite the recognized importance of ethical idealism in enhancing fraud detection in the audit context, there remains limited understanding of the mediating role of conscientiousness in the relationship between auditors’ ethical idealism and fraud detection. The purpose of this paper is to analyze the influence of auditors’ ethical idealism on fraud detection via using the conscientiousness of auditors as a mediator. This study employs a cross-sectional approach, and quantifiable data were gathered via structured surveys from 401 external auditors employed in offices licensed to practice the accounting and auditing profession in Saudi Arabia. Accidental sampling was used to ensure a representative sample of auditors in Saudi audit firms. This study utilized the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) technique to examine the relationships between ethical idealism (as independent variable), conscientiousness (as mediating variable), and fraud detection (as dependent variable). The result showed that ethical idealism has a positive effect on auditors’ detection of fraud. However, the proposed mediation effect of conscientiousness between ethical Idealism and fraud detection was not statistically significant. The research underscores that the ethical idealism of auditors can enhance fraud detection, especially when accounting firms give priority to ethical training programs, ensuring that they are guided by strong ethical idealism rather than personal conscientiousness.

1. Introduction

Fraud occurs in almost every organization throughout the world (Heliantono et al., 2020). Fraud is a persistent and serious problem, as illustrated by the recent scandals at Wirecard and Adler Group in Germany, Patisserie Valerie in the United Kingdom, Evergrande in China, and NMC Health in the United Arab Emirates (Tümmler & Quick, 2025). It is important to note that these are recent scandals that occurred between 2019 and 2024. These necessitate us to conduct more research and reviews of the literature to be able to understand this issue. According to the Legal Dictionary, fraud is the intentional use of deceit, trickery, or other dishonest means to deprive another of money, property, or legal rights (Hill & Hill, 2024). The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners detected and examined 2410; 2690; and 1921 fraud cases in 2016, 2018, and 2024 respectively with losses of USD 6.3 billion in 2016, USD 7 billion in 2018, and USD 3.1 billion in 2024 (ACFE, 2024, 2018, 2016). The ACFE has divided fraud into three broad categories, including asset misappropriation, financial reporting fraud, and corruption (ACFE, 2022). The least common type of fraud is financial statement fraud, which accounts for just 5%. However, it is the most costly, accounting for a median loss of USD 766,000 in 2024. Therefore, these frauds are of particular concern to society and stakeholders (ACFE, 2024). The early detection of fraud is crucial because it could prevent significant financial losses and protect the integrity of organizations. Early detection allows businesses to mitigate damages, preserve their reputation, and maintain stakeholder trust. Additionally, the timely identification of fraudulent activities can lead to more effective law enforcement interventions, ultimately deterring future fraudulent behavior (Lannai et al., 2021; Tümmler & Quick, 2025).

Fraud detection can be enhanced by implementing the ethical idealism of auditors. The concept of auditor ethical idealism is a moral principle that auditors should adhere to when conducting audits in order to perform high quality audits (Verwey & Asare, 2022). According to Lannai et al. (2021), ethical idealism refers to the rules and norms that govern human behavior. Following applicable ethical principles leads to the best practices in detecting fraud, and hence maintaining public confidence in the accounting profession (Idawati, 2020; Hassan, 2019; Harahap & Putri, 2018). If an audit firm is unable to implement quality control policies and practices that are well understood by all its staff, it is the responsibility of idealistic auditors to eliminate these challenges (Kerler & Killough, 2009). In reality, however, the process of detecting fraud is not as straightforward as it seems. In spite of ethical idealism, auditors may not be able to detect fraud. Auditors are evaluated based on their professional principles, ethics, and attitudes, and they must maintain moral standards (Agus et al., 2024).

Due to the various motivations and methods used for financial statement fraud, financial statement fraud is not always detected and revealed (Lannai et al., 2021). Audits are supposed to provide clients with honest, reliable, and unbiased opinions about their financial information (Hussin et al., 2017). An accounting professional code of conduct is an example of a social contract and belongs to the conscientious approach (Samagaio & Felício, 2022). When a conscientious individual is committed to moral principles, his or her actions will not be subdued until they are in accordance with these principles (Faramarzi et al., 2022). In other words, ethical idealism will strengthen auditor conscientiousness. Developing ethical idealism will enable auditors to strengthen their integrity, honesty, and objectivity, thereby enhancing their conscientiousness. As a result, conscientious auditors are quite vigilant, pay close attention to details, and remain persistent in detecting fraud during an audit (Alsughayer, 2021).

Though ethics in auditing is becoming more and more important, very little empirical research has been performed in Saudi Arabia, where new rules, digitalization, and higher public expectations of openness and responsibility are causing the audit profession to change dramatically. Saudi Arabia is quickly matching worldwide accounting and auditing norms as a G20 economy with significant changes under Vision 2030 (AlNaimi, 2022). Still, the cultural, legal, and institutional setting is unique from Western settings where much research on audit ethics is focused. This generates a significant knowledge gap in the field of how human values—such as ethical idealism and conscientiousness—affect auditor conduct in this particular environment. By closing this disparity, the study provides significant new perspectives on how ethical frameworks function in developing nations—especially in areas where audit supervision and ethical behavior are still developing.

There are numerous significant contributions to the literature that this study makes. First, it addresses limitations in previous audit-related studies generally depending on linear regression by applying Structural Equation Modeling using Partial Least Squares (SEM-PLS), a technique well-suited for investigating complex, non-normally distributed data. Second, although other studies have independently examined the effects of ethics or personality on fraud detection, this study especially examines at the mediating function of conscientiousness in the relationship between auditors’ ethical idealism and fraud detection. This integration offers a more complex perception of how individual characteristics affect ethical audit performance. Finally, the study is contextually unique as it centers on Saudi Arabia’s external auditors—a demographic not often examined in fraud detection literature. These elements, taken together, offer novel theoretical and methodological ideas on how to raise audit quality by means of ethical and personality-based elements.

Based on the gaps identified in the literature, this study is guided by the following research questions:

- To what extent does ethical idealism influence auditors’ ability to detect fraud?

- Does conscientiousness mediate the relationship between ethical idealism and fraud detection among external auditors?

Three main contributions are made in the present study. First, it offers an expanded perspective by examining how ethical idealism affects fraud detection both directly and indirectly via conscientiousness, therefore transcending research that focuses on these interactions in isolation. Second, it improves the validity of the results by applying Structural Equation Modeling using Partial Least Squares (SEM-PLS), a technique fit for analyzing complicated relationships and non-normal data. Third, by concentrating on external auditors in Saudi Arabia, the study provides insightful analysis of ethical behavior inside a Middle Eastern audit environment, therefore bridging a gap in the body of knowledge worldwide when such environments are sometimes neglected.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Introduction

The identification of fraud in financial statements is profoundly affected by the ethical principles and character attributes of auditors. Ethical idealism, the conviction that positive outcomes are perpetually attainable, informs an auditor’s dedication to ethical behavior and affects their decision-making in intricate scenarios. Conscientiousness, defined by diligence, organization, and a robust sense of responsibility, influences auditors’ work approach and compliance with professional standards (Ajina et al., 2020). Previous research has demonstrated a positive correlation between high levels of ethical idealism in auditors and an increased likelihood of detecting fraudulent financial reporting, suggesting that auditors who strongly believe in the possibility of positive ethical outcomes are more inclined to rigorously examine financial statements for irregularities and discrepancies (Indrasti & Karlina, 2020).

The interaction between ethical idealism and conscientiousness is essential in influencing auditors’ professional conduct (Kusumastuti et al., 2016). Auditors with elevated ethical idealism are more inclined to detect fraud, whereas those with high conscientiousness are more prone to adhere to procedures and focus on details, thereby enhancing the probability of identifying fraudulent activities (Heni et al., 2020). The characteristics of ethical idealism and conscientiousness substantially affect auditors’ ability to identify fraud, with this effect intensified in specific cultural and regulatory contexts (Emerson & Yang, 2012; Verwey & Asare, 2022).

However, the purpose of the current study is to analyze the influence of auditors’ ethical idealism on fraud detection via using the conscientiousness of auditors as mediators. This paper contributes to clarifying how ethical idealism, both directly and indirectly through conscientiousness, affects fraud detection. Thus, the literature review of this paper will focus on the relationship between fraud detection, ethical idealism, and conscientiousness in the auditing field. The review will lead to the development of the conceptual framework and the hypotheses of the study.

Even though there has been a lot of study on ethical behavior and fraud detection independently, there is still a lack of knowledge on how these two domains interact, especially when considering personality attributes like conscientiousness. While paying significantly less attention to the internal psychological traits of auditors themselves, most current research has concentrated on outside factors such as corporate rules, professional standards, or regulatory compliance. Though they are sometimes disregarded, factors including personal moral convictions and personality qualities might greatly influence how auditors view, understand, and handle possible fraud. Most earlier studies have also been undertaken in Western or highly developed nations, where organizational structures, legal systems, and ethical standards differ greatly from those in developing nations (Emerson & Yang, 2012; Farag & Elias, 2012). Better knowledge of how individual-level factors like ethical idealism and conscientiousness influence fraud detection behavior is needed in places like Saudi Arabia, where the auditing profession is still developing and ethical frameworks may be shaped by different cultural and institutional dynamics. By investigating how these auditor characteristics function in Saudi Arabia, the present study seeks to address that disparity.

2.2. Fraud Detection

Fraud is a deliberate act of taking advantage of an organization’s resources or wealth for personal gain (ACFE, 2016). It is an intentional violation of law for a particular purpose (manipulation or giving false information to others) that is carried out both inside and outside the organization for financial gain (ACFE, 2016). Fraud is defined by Audit Standard 240 as intentional acts committed by employees, management, or the entity responsible for governance, that involve deception in order to gain an unfair advantage or violate the law (IAASB, 2024). For the purpose of the current study, fraud is defined as financial reporting fraud and misuse of assets, excluding corruption as a form of fraud. As discussed by Hayes et al. (2014), this exclusion complies with the definition of fraud as determined by external auditors’ responsibility. According to them, fraud is defined as a deliberate inaccuracy in the financial statements.

The Fraud Triangle is a model that explains the factors that lead an individual or organization to commit fraud. This Triangle is composed of three components, Pressure, Opportunity, and Rationalization, which together lead to the commission of fraud. There are two types of pressure: the urgent need for financial resources and the perceived obligation that cannot be disseminated among others. Opportunity refers to a situation that allows a person or company to commit fraud. Rationalization is a set of values and demographics that justify certain parties committing fraud (Heliantono et al., 2020). In the financial reporting space, fraudulent financial reporting has severe repercussions for multiple stakeholders (Verwey & Asare, 2022). Thus, auditors are required to plan their audits in such a way that they are likely to detect fraud (IAASB, 2024; PCAOB, 2016). However, prior research indicates that auditors rarely detect fraud, despite the fact that the incidence of fraud continues to rise. In order to effectively evaluate fraud, it is necessary to provide evidence that an intentional misstatement took place as well as to assess the potential consequences of such an event (Nallareddy & Ogneva, 2017).

Regulators have identified ethical lapses as a major cause of auditors’ failure to detect fraud (Arirail & Crumbley, 2019; SEC, 2019). The use of ethical idealism and personality traits to gain insight into auditors’ fraud planning judgments has been limited, despite long-standing theorization suggesting that ethical idealism is associated with tolerance for deception (Forsyth, 1980). Auditors aim to ensure that audited financial statements are free from material misstatements. Professional standards outline several steps that auditors should follow when assessing financial statements for material fraud, including the following: identifying fraud risks; assessing these risks; responding to the assessment results; evaluating the resulting audit evidence; communicating the identified fraud to management; and incorporating these findings in report (IAASB, 2024; PCAOB, 2016).

The harmful consequences of fraud encourage the investigation of the role of ethical position in fraud detection (ACFE, 2024; Free & Murphy, 2015; Forsyth, 1980). Less idealistic auditors are likely to render less effective fraud judgments as they tend to favor their clients (Verwey & Asare, 2022). Auditors should be aware that when they are under pressure, they can compromise their moral standards when it comes to ethical idealism and fraud detection. As a result of ethics, auditors are able to resist such scenarios so that they can be considered technically conscientious. This attitude of resistance makes auditors more conscientious regarding the validity and integrity of the evidence provided by management. Research has demonstrated that audits of high levels of conscientiousness have greater validity (Emerson & Yang, 2012). The fact that conscientious auditors are likely to be disciplined and persistent supports the need for more rigorous fraud detection standards (Samagaio & Felício, 2022). It has been demonstrated that conscious auditors are more likely to examine management’s assertions in greater detail and to seek additional corroborating information to support their audit judgments, thus playing a crucial role in enforcing stringent levels of fraud detection (Emerson & Yang, 2012).

2.3. Ethical Idealism

Ethical idealism is a philosophy that guides one in recognizing the pertinence of moral principles and values in decision-making (Forsyth, 1980). When considered against the backdrop of auditing, ethical idealism plays an important role in shaping auditors’ behavior and attitudes regarding their professional responsibilities such as fraud detection (Rininda, 2024; Alsughayer, 2021; Ratna & Anisykurlillah, 2020; Cameran & Campa, 2020; Awaluddin et al., 2019; Putri et al., 2017; Arditiyan & Suryandari, 2016; Ashari, 2013; Farag & Elias, 2012; Cabrera-Frias, 2012; Shaub & Lawrence, 1996; Jones, 1991). High ethical idealism in auditors strengthens integrity, honesty, objectivity, and conscientiousness in auditors; so, they tend to approach work with a higher sense of moral responsibility (Alsughayer, 2021). It is more likely that highly ethical, idealistic auditors would detect fraud because of the reflection of their ethics on their decisions and actions (Cameran & Campa, 2020). For instance, such auditors will question management assertions rigorously and vigilantly against any attempts to manipulate financial reporting for personal or organizational benefit. They achieve this by meticulously examining accounting records and verifying their accuracy against established accounting standards and regulations. Auditors also assess internal control systems to ensure they effectively prevent and detect errors or fraud. Through these processes, they ensure financial statements are reliable and compliant with legal requirements (Rininda, 2024).

When an audit office does not have strict quality control policies and practices that are well-understood by all of its professionals, it is the idealistic auditors’ duty to eliminate those challenges (Kerler & Killough, 2009). Auditors are judged by their professional principles, ethics, and attitudes, and they are required to uphold moral standards. An auditor is supposed to provide honest, trustworthy, and unbiased judgments on clients’ financial information (Hussin et al., 2017). A person who is conscientious is one who performs an action or assumes their responsibility correctly. When the conscientious auditors are committed to ethical principles, they will not feel calm until their actions are in accordance with such principles. Faramarzi et al. (2022) described conscientious auditors as loyal to their families, obedient to their superior officials, ambitious, and hardworking. In other words, ethical idealism strengthens the conscientiousness of auditors. Ethical idealism strengthens the integrity, honesty, and objectivity of auditors, and hence strengthens their conscientiousness. The attribute of conscientiousness is, therefore, quite necessary to ensure that auditors are quite vigilant, pay close attention to details, and remain persistent in detection fraud during the audit (Alsughayer, 2021).

The most significant relationship between ethical idealism and fraud detection is when auditors face pressure that could compromise their moral standards. Ethics enables auditors to resist such scenarios so that they hold themselves as technically conscientious. This attitude of resistance also means auditors have a more skeptical mind when evaluating management’s evidence because they will deeply think about the validity and integrity of the kind of information provided (Arditiyan & Suryandari, 2016). Ethical idealism encourages fraud detection by auditors since it strengthens their commitment towards ethical principles and provides them with conscientiousness in situations of conflicts of interest. As a part of ethics, auditors must also be conscientious to support the integrity of the audit process in order to achieve greater financial reporting reliability and to increase stakeholder confidence (Rininda, 2024).

2.4. Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness is a component of the Big Five personality traits (Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Emotional Stability, Openness to Experiences) characterized by attributes such as organization, carefulness, industriousness, and responsibility (McCrae & Costa, 2008). A conscientious auditor is careful and thorough in his work approach, which improves fraud detection (Chen et al., 2023). McCrae and John (1992) assert that individuals with a pronounced sense of responsibility exhibit diligence, ambition, vitality, perseverance, high accountability, meticulousness, and potentially ethical behavior. Conscientious workers typically exhibit personality characteristics including organization, rigor, discipline, diligence, dependability, and technique (McCrae & Costa, 1989). In other words, conscientious workers will use their highest effort to finish the assignment, can take action to address issues, and can demonstrate work performance in accordance with business policy while concentrating on the task at hand (Emerson & Yang, 2012). An external auditor that is conscientious would probably attempt the audit with increased attention and focus on details. This will make it easier for them to spot and address any potential warning signs or fraud (Janssen et al., 2021). This attention to detail and perseverance may translate to a more rigorous fraud detection, leading to a more trustworthy and effective audit. Thus, fraud detection can be enhanced by conscientious auditors (Samagaio & Felício, 2022).

Also, previous research studies demonstrated that auditors with a high level of conscientiousness have more validity (Asare et al., 2024). Being meticulous, they can evaluate audit evidence critically, verify facts, and maintain concentration at the workplace. This will aid them in producing accurate and reliable results for the audit. Conscientious auditors are likely to be disciplined and persistent, hence, they support the applicability of a more rigorous fraud detection level (Samagaio & Felício, 2022). They tend to have a sense of responsibility and are unlikely to compromise on shortcuts or assumptions without sufficient evidence. Due diligence-oriented efforts focus attention on inconsistencies or red flags that may indicate misstatements or fraud. There is evidence that conscious auditors are likely to probe management’s assertions more extensively and seek supplementary corroborative evidence to support their audit judgment, therefore playing a crucial role in enforcing stringent degrees of fraud detection (Emerson & Yang, 2012).

The more conscientious a person is, the more disciplined, diligent, precise, and reliable he or she tends to be. In contrast, individuals with lower scores in conscientiousness tend to be more negligent, disorganized, lazy, and lack purpose and direction, as well as more flexible, spontaneous, and impulsive (Christiansen & Tett, 2013). A conscientious employee behaves morally as a function of their belief in their individual inherent morality as well as their understanding and appreciation of ethical inclinations (Archontikis & Galanakis, 2022). They maintain their ethical idealism by not succumbing to seemingly inevitable matters such as time pressures and client pressures. In addition, a conscientious individual usually has proactive internal activities such as ethical idealism for learning and developing their skills, which contributes to detecting fraud (Abdo et al., 2022). Ethical idealism allows for the learning of new auditing standards and strengthening the integrity, honesty, and objectivity of auditors, which leads to strengthening their conscientiousness. The attribute of conscientiousness is, therefore, quite necessary to ensure that auditors are quite vigilant, pay close attention to details, and remain persistent in detection of fraud when performing the audit (Alsughayer, 2021).

2.5. The Attribution Theory

The grand theoretical foundation for this research is the Attribution Theory. Originally published by Heider (1958) and developed by Kelley (1973), the Attribution Theory clarifies how individuals understand and attribute causes to events and actions. The idea is frequently applied in organizational behavior and psychology to explain the internal (dispositional) as opposed to external (situational) elements influencing professional behavior. Particularly in the identification of fraud, the theory helps explain how internal characteristics, including ethical idealism and conscientiousness influence an auditor’s judgment, conduct, and decision-making processes in the framework of auditing. This paper uses the internal dimension of Attribution Theory to propose that auditors’ capacity to identify and react to fraudulent conduct is much influenced by these personal inclinations.

Attribution Theory is a basic theory that is frequently used to study factors that affect auditor performance. The term “attribution theory” describes the mental behavior of people and how it is employed to make judgments about the variables influencing other people’s conduct (Kelley & Michela, 1980). Attribution Theory posits that when elucidating another individual’s conduct, people attach causality either to the individual (dispositional or internal traits) or to the situation (environmental or external factors) (Heider & Simmel, 1944; Kelley, 1973). Several factors affect auditor performance, including ethical and personality traits (Agus et al., 2024). The Attribution Theory explains how we judge individuals differently depending on the meaning we assign to certain behaviors. According to this theory, people attempt to determine whether a given behavior is caused internally or externally when they observe an individual’s behavior (Ross & Nisbett, 2010). For the purpose of the current research, the focus is on the internal attributes of the Attribution Theory only.

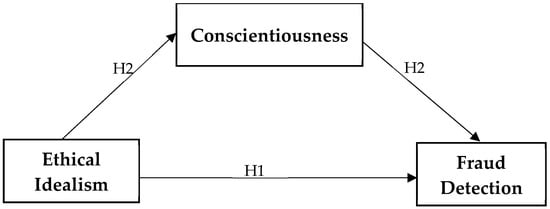

To support auditors’ performance in fraud detection, auditors need to understand their ethical idealism and how it affects their conscientiousness. The auditor’s function requires ethical idealism to achieve more optimal performance in fraud detection. In this research, Attribution Theory (internal attributes section) is used to explain how the ethical idealism of auditors can influence the auditor’s ability to detect fraud via conscientiousness. As a result of the discussion above, Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of the study.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework.

Despite the growing body of literature on ethical decision-making, a striking gap remains in our understanding of the relationship between ethical principles and individual characteristics, particularly as it pertains to auditing. Particularly, the relationship between conscientiousness—traits like thoroughness and responsibility—and ethical idealism—a person’s commitment to do what is ethically right—has not been adequately investigated in how it affects an auditor’s capacity to identify fraud. In non-Western environments, where cultural standards and legal systems can influence ethical behavior differently than in Western nations, this disparity is even more evident. The present study presents a novel paradigm based on Attribution Theory to solve this and clarifies how people’s internal characteristics affect their behavior. This study offers novel insights on how personal ethics and personality mix to influence professional judgment by gathering and evaluating data from outside auditors in Saudi Arabia. These results not only advance scholarly knowledge but also provide useful direction for enhancing ethical standards in the auditing field, especially in developing countries.

2.6. Research Hypotheses

Based on the purpose of this paper, which is to analyze the influence of auditors’ ethical idealism on fraud detection via the conscientiousness of auditors, and based on the literature review and the Attribution Theory discussed above, the hypotheses of the research can be formulated as follows:

H1.

Ethical idealism has a positive effect on auditors’ detection of fraud.

H2.

Ethical idealism has a positive effect on auditors’ detection of fraud through conscientiousness.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Introduction

According to Kothari (2004), a research methodology is a specific strategy selected to investigate a subject and its related issues from a theoretical perspective. It entails the practical aspects of data collection, analysis, interpretation, and understanding. It focuses on research achieving particular objectives (Klassen et al., 2012). Numerous research techniques are used to gather, examine, and interpret data as well as to determine how well they address particular issues (Klassen et al., 2012). Any study must carefully consider the nature of the topic before selecting an appropriate research methodology. This study aims to shed light on the influence of auditors’ ethical idealism on fraud detection via using the conscientiousness of auditors as a mediator. The study employs quantitative data analysis to assess the relationships between significant factors. External auditors working in Saudi offices licensed to practice the accounting and auditing profession were requested to fill out structured questionnaires to collect quantitative data. The surveys include their opinions and emotions towards ethical idealism, fraud detection, and conscientiousness.

To examine the relationships between ethical idealism, conscientiousness, and fraud detection, this research used Structural Equation Modeling with Partial Least Squares (SEM-PLS). SEM-PLS was chosen for a valid reason, among other things. First, especially when the aim is to investigate both direct and indirect (mediating) effects inside a single model, SEM-PLS is ideally suited for exploratory or theory-building research. Second, unlike Covariance-Based SEM, SEM-PLS does not depend on multivariate normality, which is crucial in this study considering that the data distribution diverged much from normality (as revealed by the Cramér–von Mises test findings). Third, both of which apply to this study, SEM-PLS is appropriate for models with smaller to intermediate sample numbers and reflecting components (Islam & Ali Khan, 2024). SEM-PLS is, therefore, perfect for combining personality characteristics, ethical orientations, and performance-based results as it offers strong estimates even when indicators have distinct measuring scales. These methodological attributes make SEM-PLS the most suitable option for the aims and data features of this research (Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, 2012).

3.2. Research Design

The study provides explanations through a quantitative method and a cross-sectional approach. The purpose of using this explanation design is to investigate the relationship between the ethical idealism of auditors and their ability to detect fraud through using their conscientiousness. Quantifying variables like ethical idealism, fraud detection, and conscientiousness is the main emphasis of the study, which collects data using structured surveys. The research is cross-sectional, so it only gathers data at one point in time; this gives an accurate representation of the level of auditors’ ethical idealism and conscientiousness and their performance regarding fraud detection. This design is suitable for testing the study hypotheses and for investigating the direct and indirect impacts of the study variables.

3.3. Sample Size

The study targets external auditors employed in offices licensed to practice the accounting and auditing profession in Saudi Arabia. The positions and educational backgrounds of participants will be used to capture a wide range of auditors’ attitudes and behaviors. The population of external auditors in Saudi Arabia is unknown. Therefore, the accidental sampling method was used to ensure a representative sample size. The sample was determined using Daniel (1999)’s infinite sample size formula. Daniel (1999)’s infinite sample size formula is applied by using a standard confidence level, typically 95%, and an acceptable margin of error, often set at 5%. The formula accounts for the variability within the population and ensures that the sample size is sufficient to make statistically significant inferences. This method is particularly useful when the total population size is large or unknown, as it provides an accurate estimate for the required sample size. Following this method the sample size was determined to be 384 auditors. A total of 415 responses were obtained, and 14 questionnaires were excluded because they were filled out by non-external auditors. This resulted in a total of 401 valid responses, yielding a response rate of approximately 104%, which exceeds the initially determined sample size. The high response rate enhances the reliability and validity of the study, ensuring that the findings are representative of the population of external auditors in Saudi Arabia. This robust response allows for more accurate generalizations and insights into the practices and perspectives within the profession.

3.4. Data Collection

The research employed a questionnaire to collect data. The questionnaire comprised two sections: one for gathering respondent characteristics and another for assessing ethical idealism, conscientiousness, and fraud detection among respondents. The questionnaire was distributed via the official email registered for the Saudi audit firms and was also distributed manually to a group of Saudi audit firms around the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The questionnaire was presented in multiple forms to ensure it was filled out by the study population. It was presented as a paper copy, electronic link, and quick response code. Participants’ identities were safeguarded using data anonymization techniques, therefore guaranteeing their confidentiality. The data-collecting process was intended to avoid biases, including selection bias. The studies followed ethical standards, including informed permission, data protection, and confidentiality. Participants were offered informed permission before data collection. Only the research team has access to the private data. Protection is guaranteed by secure online data collection and storage.

During data collection, several challenges were encountered. One major issue was the low response rate, as many auditors were either too busy or hesitant to participate due to confidentiality concerns. Additionally, technical difficulties with the electronic links and quick response codes occasionally hindered the accessibility and completion of the questionnaires. To address these challenges, follow-up reminders were sent to encourage participation and alleviate confidentiality concerns. Additionally, technical support was provided to resolve issues with the electronic links and quick response codes, ensuring that all auditors had equal access to the questionnaire. This method ensured a diverse sample of external auditors.

3.5. Data Analysis

This study uses the SEM technique to calculate path coefficients and loadings to evaluate the measurement model for ethical idealism indicators, conscientiousness indicators, and fraud detection indicators. This stage determines the validity of the relations between observable variables and theoretical concepts. Bootstrapping examines hypothesis robustness and statistical significance by establishing confidence intervals for path coefficients. This method verifies the relationships’ consistency and validity to exclude chance. This combination provides a robust foundation for examining the model’s structural and measurement qualities, delivering accurate and insightful results. Researchers can use Performance Map Analysis (IPMA) to discover which efforts boost fraud detection. Together, these methods reveal how idealistic auditors act on fraud detection.

3.6. Measurement of Variables

Using a structured survey instrument, this study measures variables related to the ethical idealism of auditors, the conscientiousness of auditors, and the ability of auditors to detect fraud. To guarantee accuracy and consistency, all measurements were taken from previous research (Verwey & Asare, 2022; Said & Munandar, 2018; Fullerton & Durtschi, 2004; Gosling et al., 2003; Forsyth, 1980). This ensures that these selected measurements were very well tested and validated by many researchers. The following three paragraphs illustrate these three measurements.

The Forsyth (1980) ethical stance scale is used to measure the external auditor’s ethics. This scale includes 20 questions in all; these questions are divided into two main parts which are: “(1) Idealism; and (2) Relativism. Idealism scores are calculated by summing responses from items 1 to 10. Relativism scores are calculated by summing responses from items 11 to 20” (Forsyth, 1980). The responses indicate the degree of agreement with each item using a scale that ranges from 1 = Completely disagree; 2 = Moderately disagree; 3 = Slightly disagree; 4 = Neither agree nor disagree; 5 = Slightly agree; 6 = Moderately agree; 7 = Completely agree. This paper utilized only the first five items of the ethical idealism scale to fulfill its objectives.

The Ten-Item Personality Inventory (Gosling et al., 2003) is used to measure the external auditor’s personality traits. This scale includes Ten-item to measure the Big Five personality traits which are: (1) Extraversion (sociable, talkative, assertive, active, NOT shy, or reserved); (2) Agreeableness (trusting, sympathetic, generous, cooperative, NOT cold, or aggressive); (3) Conscientiousness (hard-working, thorough, responsible, self-disciplined, NOT impulsive, or careless); (4) Emotional Stability (self-confident, relaxed, NOT moody, anxious, easily stressed, or easily upset); (5) Openness to Experiences (curious, reflective, open-minded, creative, deep, NOT conventional). Each one of the Big Five personality traits has two items, one of them is a reverse-scored item and the other is a standard item. These ten items have been measured using a 7-point scale that varies between 1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Moderately disagree; 3 = A little disagree; 4 = Neither agree nor disagree; 5 = A little agree; 6 = Moderately agree; 7 = Strongly agree. The responders should evaluate the degree to which each attribute applies to them, regardless of whether one characteristic is more dominant than the other. TIPI scale is scored as the following “(“R” denotes reverse-scored items): Extraversion: 1, 6R; Agreeableness: 2R, 7; Conscientiousness; 3, 8R; Emotional Stability: 4R, 9; Openness to Experiences: 5, 10R” (Gosling et al., 2003). The Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) is assessed by calculating the average of the two items that constitute each of the Big Five personality traits. To achieve the objectives of this paper, only the scale of conscientiousness was used.

The variable of the external auditor’s ability to detect fraud is measured by the fraud indicator scale (Fullerton & Durtschi, 2004). There are 42 questions in all. These questions are divided into three main parts related to fraud symptoms, which are: (1) symptoms pertaining to the business environment; (2) symptoms associated with the culprit; and (3) symptoms that relate to financial records and accounting practices. To achieve the objectives of this paper, only the third part (symptoms that relate to financial records and accounting practices) of the scale was used. The respondents were asked to indicate to what degree they would want to expand their search for information if they observed a specified situation. Responses in this section are also marked on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 = not at all to 6 = a great deal. The operational definitions of study variables are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Operational Definitions of Study Variables.

Although the inclusion of validated measures such as Forsyth’s Ethical Stance Scale, Gosling’s TIPI, and Fullerton and Durtschi’s Fraud Indicator Scale improves the methodological rigor of this research, it is crucial to recognize that these instruments depend on self-assessment. Participants must reflect on their ethical standards, conscientiousness, and judgment capacity, therefore adding a degree of subjectivity. Social desirability bias, self-perception errors, or overconfidence might all affect such self-reported assessments, hence compounding what has been called a “double-dip” into subjectivity. Complementing self-report data with supervisor evaluations, peer assessments, or scenario-based audit simulations can help future studies validate constructs and reduce bias. Despite this restriction, the use of already validated scales offers a useful basis for exploratory insight into these psychological and behavioral variables within the audit setting.

4. Data Analysis and Interpretation

The study utilized measurement and structural models in this study to comprehensively analyze the relationship between ethical idealism and fraud detection, mediated by conscientiousness within the audit context. The measurement approach enabled the assessment of the validity and reliability of the variables under investigation, ensuring that the data accurately represented the core constructs (Chua, 2023). Techniques such as confirmatory factor analysis were employed, alongside evaluations of both convergent and discriminant validity, to verify the reliability of the measurement instruments (Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016). The structural model allowed exploring the complex interrelationships between the variables and examining their impact on fraud detection. Through the application of structural equation modeling, the research effectively visualized the connections between variables, providing a detailed understanding of the underlying mechanisms that drive the observed outcomes (Hair et al., 2019). Consequently, the integration of measurement and structural models established a robust methodological framework for this study, facilitating a confident and rigorous investigation into the influence of ethical idealism on fraud detection, mediated by conscientiousness in the audit context.

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

Positive median values and negative skewness for all dimensions imply that auditors in the sample rated themselves above average on conscientiousness, ethical idealism, and fraud detection. This is supported by descriptive statistics. Conscientiousness and ethical idealism had peaked (leptokurtic), implying most respondents concentrated around higher values with few low outliers. Though they were somewhat more balanced, fraud detection ratings still tended towards greater self-assessment. The Cramér–von Mises test (p < 0.001) indicated that all three constructs greatly departed from a normal distribution, therefore supporting the use of non-parametric approaches such as PLS-SEM to examine the interactions among these variables, as mentioned in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Main Variables.

4.2. Model Measurement

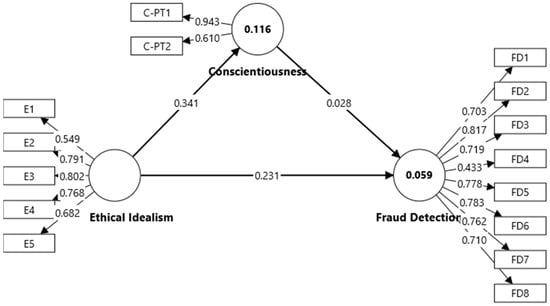

Figure 2 presents the measurement model, a crucial statistical technique for evaluating the robustness of the study. It is an approach to access and validate the robustness of the model. Determining factor loadings offers a straightforward method to assess the alignment between measures and underlying constructs. The key components of a measurement model, validity, and reliability should be examined to determine its quality. Metrics such as composite reliability, Cronbach’s alpha, and average variance extracted (AVE) are commonly used for this purpose. Employing a robust measurement technique underpins empirical research, lending it legitimacy and rigor, while also laying the groundwork for future investigations (Hair et al., 2020).

Figure 2.

Measurement Model.

Accounting for factor loadings and measurement error, Table 3 shows the composite reliability values (ρa and ρc) evaluating how consistently a set of items assesses a given construct. While ρa provides an adjusted estimate usually chosen in PLS-SEM owing to its resilience against loading bias, composite reliability (ρc) analyses internal consistency more precisely than Cronbach’s alpha. Combining both tests improves the evaluation of dependability.

Table 3.

Construct reliability and validity.

The results reveal different degrees of dependability among the constructs. Although conscientiousness has a low Cronbach’s alpha (0.475), showing weak internal consistency, its composite reliability (ρa = 0.713; ρc = 0.656) and AVE (0.631) are within reasonable levels, therefore indicating moderate construct dependability. Although one item (C-PT2) exhibited a somewhat low factor loading (0.61), the other item (C-PT1 = 0.943) corrected, thereby confirming retention of the construct owing to the theoretical significance and suitable overall measurements. Regarding both items, the VIF values (1.107) show no multicollinearity issues.

With Cronbach’s alpha (0.772), ρa (0.801), and ρc (0.845), Ethical Idealism displayed strong consistency above the recommended 0.70 level. Although one indicator (E1 = 0.549) dropped somewhat below the recommended loading of 0.70, its inclusion was supported based on content authenticity and since the total AVE (0.525) stayed above the acceptable threshold. For every item, VIF values were less than two, therefore verifying indication independence.

With a high Cronbach’s alpha (0.868), ρa (0.894), ρc (0.895), and reasonable AVE (0.521), Fraud Detection showed the strongest measurement qualities. Though one item (FD4 = 0.433) fell below the average threshold, most loadings were above 0.70. This item was kept because of its conceptual importance, since general construct dependability stayed good. Suggesting no multicollinearity issues, the VIF values for every item varied from 1.247 to 2.263.

With reasonable degrees of internal consistency, convergent validity, and indicator relevance across constructions, the reliability and validity results generally supported the idea that the measurement model is suitably strong for structural modeling.

Table 4 presents the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio, a metric used to assess the uniqueness of each construct. HTMT values are derived by examining the relationships between different constructs and the correlations within a single construct, known as monotrait correlations. The Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio values indicate the level of discriminant validity between the constructs. The HTMT value between conscientiousness and Ethical Idealism is 0.497, which is below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.85, suggesting that these two constructs are sufficiently distinct. The HTMT value between conscientiousness and Fraud Detection is 0.192, indicating a low correlation and strong discriminant validity. Similarly, the HTMT value between Ethical Idealism and Fraud Detection is 0.278, further confirming that these constructs are distinct. Overall, the results suggest that discriminant validity is well established, as none of the HTMT values exceed the recommended threshold.

Table 4.

Discriminant Validity (HTMT).

Table 5 represents the R-square values for the constructs, indicating the amount of variance explained by the model. Conscientiousness has an R-square of 0.116, suggesting that the model explains about 11.6% of the variance in this construct, which is relatively low. Fraud Detection has an R-square of 0.059, indicating that only about 5.9% of the variance is explained, which is also a modest amount. These values suggest that while the model captures some of the variance, there are likely other factors not accounted for in explaining these constructs.

Table 5.

Model Fit and Effect Size Indicators.

The f-square values reveal the strength of the relationships between the variables. The relationship between conscientiousness and Fraud Detection is very weak, with an effect size of 0.001, indicating almost no impact. On the other hand, the relationship between Ethical Idealism and conscientiousness shows a moderate effect, with an f-square value of 0.131, suggesting a small but meaningful influence. The effect of Ethical Idealism on Fraud Detection is similarly small, with an f-square value of 0.050, indicating a minor impact.

The model fit indicators suggest that the model is close to an acceptable fit. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) value (0.074) is slightly below the recommended threshold of 0.08, indicating a reasonably good fit. The Unweighted Least Squares discrepancy (d_ULS) (0.663) and Geodesic Distance (d_G) (0.175) values are within acceptable ranges, further supporting model consistency. While the Chi-square value (422.326) is relatively high, this is common in larger sample sizes. The Normed Fit Index (NFI) (0.796) is approaching the recommended threshold of 0.90, suggesting that the model fit could be improved but remains within a reasonable range. Overall, the results indicate that the model demonstrates a moderately acceptable fit, with some room for refinement.

4.3. Structural Model

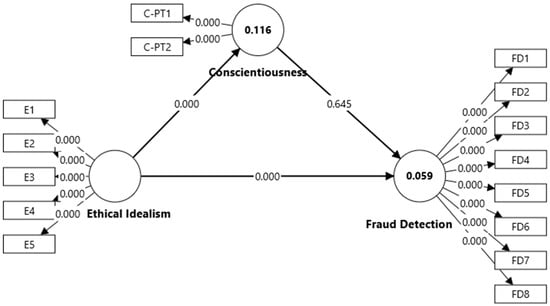

The structural model serves as a visual representation for constructing a Structural Equation Model (SEM). This approach facilitates the acquisition of knowledge by integrating the primary components that form the foundation of the study. The structural model facilitates the formulation of reliable hypothesis–testing links between theoretical constructs and their empirical indicators, as well as among the constructs themselves. Additionally, it permits the concurrent utilization of many indicator variables for each construct. Path factors elucidate the extent and orientation of these interactions. This method can be utilized to validate concepts and ensure a systematic organization of the structure (Prayitno et al., 2021). The visual representation of the structural model is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Structural Model.

The hypothesis testing analysis presented in Table 6 provides significant and insightful perspectives. Path coefficients and t-values indicate the strength and relevance of these interactions. H1 (Ethical Idealism -> Fraud Detection) shows a significant positive relationship, with a t-statistic of 4.719 and a p-value of 0.000, since the p value is less than 0.05, the hypothesis is accepted. On the other hand, H2 (Ethical Idealism -> conscientiousness -> Fraud Detection) shows a very weak effect, with an original sample value of 0.009 and a t-statistic of 0.437, which is below the commonly accepted threshold of 1.96 for significance. Additionally, the p-value of 0.662 is much higher than the 0.05 threshold, indicating that this indirect relationship (via conscientiousness) is not statistically significant. As a result, the hypothesis is rejected, meaning that the proposed mediation effect for conscientiousness between Ethical Idealism and Fraud Detection is not statistically significant.

Table 6.

Hypothesis Testing.

Additionally, with a p-value of 0.000, the findings in Table 5 show that Hypothesis 1 (H1), which holds a direct positive association between ethical idealism and fraud detection, is statistically significant. This implies that the outcome is quite significant (p < 0.01), thereby indicating strong support for the claim that more ethical idealism improves auditors’ capacity to identify fraud. By comparison, Hypothesis 2 (H2), which suggested a mediating function of conscientiousness in the link between ethical idealism and fraud detection, had a p-value of 0.662. Conscientiousness does not clearly moderate this link in the current model as indicated by this non-statistically significant (p > 0.05). H2 is disregarded as there is no significant indirect influence.

Again, indicating a statistically significant and regularly positive connection, the confidence interval for the direct effect of ethical idealism on fraud detection ranges from 0.140 to 0.337. By comparison, the confidence range for the indirect impact via conscientiousness runs from −0.050 to 0.086, including zero. This implies that conscientiousness does not significantly change the mediating effect, which is low and not statistically significant, so the influence of ethical idealism on fraud detection is not clear.

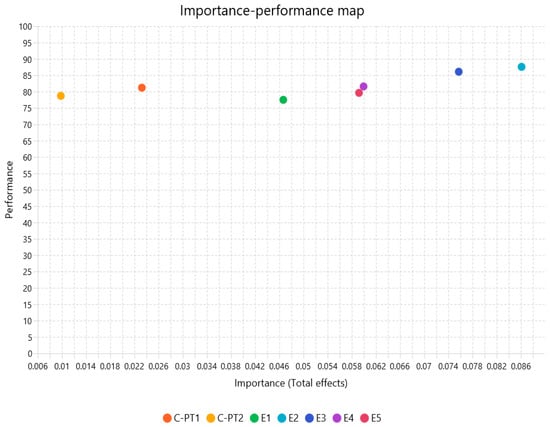

Importance-Performance Map Analysis (IPMA) in PLS-SEM is a technique used to assess the relative importance and performance of different constructs and their indicators in a model. It helps identify which variables have the greatest impact on the target construct and where improvements can be made by combining both the importance and performance of variables (Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016). Measurement Variable (MV) Performance refers to the observed indicators used to measure the latent constructs in the model (Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016). In the present study, IPMA and MV performance are used to assess the relationship between key factors and their impact on fraud detection. MV performance helps quantify the effectiveness of different attributes, while IPMA highlights areas where improvements can maximize overall outcomes. This approach ensures a clear understanding of which factors significantly influence fraud detection and where strategic efforts should be focused. Table 5 shows that ethical issues (E1–E2) perform well but vary in relevance, indicating strategic focus. Dependability (C-PT1) and organization (C-PT2) are low-priority but high-performing, suggesting they may not be improvement priorities. The poor fraud detection rates emphasize the need for focused measures to match importance with performance, as shown in Table 7 and Figure 4.

Table 7.

IPMA—Analysis.

Figure 4.

IPMA.

5. Discussions

Based on the structural model created to evaluate the links among ethical idealism, conscientiousness, and fraud detection, this part shows the results of the research. The results are reviewed concerning pertinent literature and theoretical underpinnings, given the suggested hypothesis.

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the role of ethics, conscientiousness, and fraud detection. The structural model assessment reveals interesting patterns in the relationships between these variables. As shown in Appendix A, the study indicated a small and negligible direct effect of conscientiousness on fraud detection (β = 0.028, p = 0.645). This implies that conscientiousness alone may not improve fraud detection. One rationale is that conscientious people are careful and responsible, but fraud detection takes deeper understanding to comprehend the behavior of fraudulent. Specialized expertise, analytical abilities, and some external incentives are often required (Bolton et al., 2010; Berry et al., 2007; Bennett & Robinson, 2000). Although personality qualities might affect ethical behavior, fraud detection is usually driven by systematic processes, technological instruments, and regulatory control (Abiola, 2013). The study indicates a significant positive relationship between ethics and conscientiousness (β = 0.341, p < 0.001). This supports previous research that shows conscientiousness increases with ethical ideals (Faramarzi et al., 2022). Idealistic auditors are more disciplined, accountable, and thorough, which promotes conscientiousness (Samagaio & Felício, 2022). These findings imply that ethical training and organizational culture should be prioritized to promote employee conscientiousness. A significant positive correlation (β = 0.241, p < 0.001) suggests that ethical concerns are vital in detecting fraudulent activity. This supports previous study that ethical awareness improves fraud detection (Rininda, 2024; Alsughayer, 2021; Verwey & Asare, 2022; Ratna & Anisykurlillah, 2020; Cameran & Campa, 2020; Arirail & Crumbley, 2019; Awaluddin et al., 2019; Putri et al., 2017; Arditiyan & Suryandari, 2016; Free & Murphy, 2015; Ashari, 2013; Farag & Elias, 2012; Cabrera-Frias, 2012; Shaub & Lawrence, 1996; Jones, 1991). Strong idealistic employees are more likely to report unethical behaviors, investigate suspicious activity, and follow company standards (Henle et al., 2005). Research suggests that ethical training programs might enhance fraud detection by increasing awareness of unethical behavior (Heliantono et al., 2020).

As shown in Table 5, findings from the Importance-Performance Map Analysis (IMPA) provide light on how important ethical principles and diligence are for detecting fraud. “One should never psychologically or physically harm another person” (E2) stands out among the ethical considerations, with the highest influence on fraud detection (0.086) and performance value (87.583). This emphasizes its significance in influencing ethical behavior and preventing fraud. The significance of ethical responsibility in identifying and preventing fraudulent activities is further emphasized by the statements “One should not perform an action which might in any way threaten the dignity and welfare of another individual” (E4, impact = 0.06, performance = 81.583) and “If an action could harm an innocent other, then it should not be done” (E3, impact = 0.076, performance = 86.083). According to Samagaio and Felício (2022), previously published research has shown that being ethically conscious improves one’s ability to identify fraud since it promotes a moral code that forbids immoral actions. Having a high level of conscientiousness is not a substantial predictor of fraud detection. Attributes associated with conscientiousness, such as dependability and self-discipline, have a lesser importance (C-PT1, effect = 0.023, performance = 81.208), which supports previous statistical findings. While broad ethical concerns are important, it is more critical to focus on particular moral principles that address harm and welfare when trying to detect fraud. One such principle is “People should make certain that their actions never intentionally harm another even to a small degree” (E1, impact = 0.047, performance = 77.5), which has a moderate impact. Instead of solely focusing on character attributes like conscientiousness, these findings show how important it is for companies to implement ethical training programs that teach employees to have strong moral convictions (refer to Appendix A for details).

The findings complement other studies (e.g., Alsughayer, 2021; Rininda, 2024) stressing the key part that ethical orientation plays in determining the professional behavior of auditors. The major direct influence of ethical idealism supports the view that auditors’ attentiveness in spotting fraud depends critically on moral values, especially the conviction in doing no harm. Conversely, the non-significant mediation effect of conscientiousness implies that, although crucial, personality qualities like diligence and organization do not either strengthen or diminish the influence of ethical idealism in this regard. This outcome runs counter to research such as Emerson and Yang (2012), which discovered that ethical auditing behavior is much influenced by conscientiousness. Theoretically, these findings support the relevance of Attribution Theory in the field of auditing. According to the notion, knowledge of ethical behavior depends mostly on internal characteristics like ethical idealism. This study clarifies that in fraud detection moral orientation is more important than personality-based discipline.

For regulatory authorities and audit firms, these results have practical consequences. Training courses should stress ethical thinking, moral judgment, and value-based decision-making more highly than they would technical ability or procedural discipline. More successful than personality screening alone are ethical awareness initiatives, ethical problem simulations, and ethics-based performance assessments in improving fraud detection results.

6. Conclusions

The purpose of this paper is to analyze the influence of auditors’ ethical idealism on fraud detection via using the conscientiousness of auditors as a mediator. This study employs a cross-sectional approach, and quantifiable data were gathered via structured surveys from 401 external auditors employed in offices licensed to practice the accounting and auditing profession in Saudi Arabia. This study indicates that ethical idealism is more important than conscientiousness in fraud detection. The data show that ethical idealism, especially damage reduction and dignity, has more impact on fraud detection. Importance-Performance Map Analysis (IMPA) stresses that ethical decision-making depends on principles, including preventing psychological or physical damage and prioritizing social welfare. Ethical awareness and moral reasoning improve fraud detection, while ethical idealism contributes to conscientiousness, and conscientiousness has a negligible effect on fraud detection. To increase fraud detection measures, organizations should prioritize ethical training and awareness programs to ensure that personnel are guided by strong ethical idealism rather than personal conscientiousness. Theoretically, ethical idealism helps identify fraud, whereas conscientiousness does not.

6.1. Implications of the Study

This study presents significant theoretical and practical ramifications for the auditing profession. It theoretically enhances the existing literature by illustrating the impact of ethical idealism on auditors’ conscientiousness and their capacity to identify fraud. This research helps us understand how thinking and behavior influence ethical performance in audits by combining ideas from ethical orientation and personality psychology. The findings underscore the importance of accounting for individual personality traits and ethical convictions in the selection and training of auditors. Audit firms could gain advantages by integrating psychological evaluations, especially regarding ethical idealism, into their recruitment and professional development strategies to improve auditors’ proficiency in detecting fraud. Moreover, ethics training programs in audit firms may be more effective when combined with strategies that promote conscientious behavior, including responsibility, diligence, and perseverance. This study offers culturally pertinent insights within the Saudi Arabian context, illustrating the functioning of personal ethics and traits amid the region’s distinct professional and societal norms.

6.2. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Despite the value of the study’s findings, it is important to acknowledge several limitations. First, the research was conducted solely within Saudi Arabia, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other countries with different regulatory, cultural, or professional auditing environments. Second, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the risk of social desirability bias, particularly given the sensitive nature of topics such as ethics and fraud detection. Third, using a cross-sectional research design limits the ability to determine cause-and-effect relationships between ethical idealism, conscientiousness, and fraud detection. Fourth, the study focused exclusively on conscientiousness as a mediating variable, potentially overlooking the influence of other relevant personality traits such as openness or agreeableness. Lastly, the measurement of fraud detection capability was based on perceived or self-assessed competence, which may not accurately reflect actual performance or outcomes in real-world audit settings.

Future studies can build on the findings of the current study by addressing the limitations and expanding the research scope. One direction for future research is to conduct comparative studies across different cultural and regulatory environments to examine whether the mediating role of conscientiousness holds in diverse audit contexts. Employing a longitudinal research design would also be beneficial in establishing stronger causal inferences and understanding how auditors’ ethical orientation and personality traits evolve. Researchers could also explore a broader range of personality characteristics, such as the full Big Five model (Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional Stability, and Openness to Experiences), to gain a more comprehensive view of how different traits influence ethical behavior and fraud detection. Furthermore, future studies should look at using real ways to measure how well fraud detection works, like practice audit tasks or evaluations from supervisors, to confirm what people say about their results. Investigating organizational and situational factors—such as audit firm culture, leadership style, and team dynamics—could also provide more profound insights into the environmental influences on ethical decision-making. Lastly, it may be useful to examine the role of demographic variables like gender, years of experience, and professional certification in shaping the relationship between ethical idealism, personality traits, and fraud detection effectiveness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A., Y.B. and H.B.; methodology, A.A.; software, A.A.; validation, A.A., Y.B. and H.B.; formal analysis, A.A.; investigation, A.A.; resources, A.A.; data curation, A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A., Y.B. and H.B.; visualization, A.A., Y.B. and H.B.; supervision, Y.B. and H.B.; project administration, Y.B. and H.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by King Abdulaziz University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical review and approval were waived for this study, for the reason that this study was conducted individually and independently by the institution where they work, respecting the anonymity of the interviewer.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Total effect.

Table A1.

Total effect.

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conscientiousness -> Fraud Detection | 0.028 | 0.032 | 0.060 | 0.461 | 0.645 |

| Ethical Idealism -> Conscientiousness | 0.341 | 0.350 | 0.056 | 6.117 | 0.000 |

| Ethical Idealism -> Fraud Detection | 0.241 | 0.253 | 0.051 | 4.719 | 0.000 |

References

- Abdo, M., Feghali, K., & Zgheib, M. A. (2022). The role of emotional intelligence and personality on the overall internal control effectiveness: Applied on internal audit team member’s behavior in lebanese companies. Asian Journal of Accounting Research, 7(2), 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiola, J. (2013). The impact of information and communication technology on internal control’s prevention and detection of fraud. De Montfort University. [Google Scholar]

- Agus, R. M., Usman, A., & Sundari, S. (2024, December 6–8). Determinant of auditor’s ability to detect fraud. IECON: International Economics and Business Conference (Vol. 2, pp. 1–12), Osaka, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Ajina, A. S., Roy, S., Nguyen, B., Japutra, A., & Al-Hajla, A. H. (2020). Enhancing brand value using corporate social responsibility initiatives: Evidence from financial services brands in Saudi Arabia. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 23(4), 575–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlNaimi, S. M. (2022). Economic diversification trends in the Gulf: The case of Saudi Arabia. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 2, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsughayer, S. A. (2021). Impact of auditor competence, integrity, and ethics on audit quality in Saudi Arabia. Open Journal of Accounting, 10(04), 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archontikis, K., & Galanakis, M. (2022). Implications of conscientiousness for ethical leadership: The new role of organizational psychology. Psychology, 12(12), 925–932. [Google Scholar]

- Arditiyan, A. K., & Suryandari, D. (2016). Influences of experiences, competencies, independence and professional ethics toward the accuracy of audit opinion delivery through auditors’ professional skepticism as an intervening variabel. Accounting Analysis Journal, 5(3), 238–247. [Google Scholar]

- Arirail, D., & Crumbley, L. (2019). PwC and the colonial bank fraud: A perfect storm. Journal of Forensic and Investigative Accounting, 11(3), 440–458. [Google Scholar]

- Asare, S. K., van Brenk, H., & Demek, K. C. (2024). Evidence on the homogeneity of personality traits within the auditing profession. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 99, 102584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashari, A. (2013, April 4–5). Corruption awareness, ethical sensitivity, professional skepticism and risk of corruption assessment: Exploring the multiple relationship in Indonesian case. 2013 Financial Markets & Corporate Governance Conference, Wellington, New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). (2016). Report to the nations: On occupational fraud and abuse: 2016 global fraud study. ACFE. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). (2018). Report to the nations: 2018 Global study on occupational fraud and abuse. ACFE. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). (2022). Occupational fraud 2022: A report to the nations. ACFE. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). (2024). Occupational fraud 2024: A report to the nations. ACFE. [Google Scholar]

- Awaluddin, M., Wardhani, R. S., & Sylvana, A. (2019). The effect of expert management, professional skepticism and professional ethics on auditors detecting ability with emotional intelligence as modeling variables. International Journal of Islamic Business an Economics, 3(1), 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, C. M., Ones, D. S., & Sackett, P. R. (2007). Interpersonal deviance, organizational deviance, and their common correlates: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, L. R., Becker, L. K., & Barber, L. K. (2010). Big Five trait predictors of differential counterproductive work behavior dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(5), 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Frias, L. (2012). The ethics of professional skepticism in public accounting: How the auditor-client relationship impacts objectivity. Georgetown University. [Google Scholar]

- Cameran, M., & Campa, D. (2020). Crticial thinking in today’s accounting education: A reflection note following the international ethics standards board for accountants consultation paper ‘professional skepticism meeting public expectations’. Accounting, Finance & Governance Review, 26(1), 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. H., Wang, K. J., & Liu, S. H. (2023). How personality traits and professional skepticism affect auditor quality? A Quantitative Model. Sustainability, 15(2), 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, N., & Tett, R. (2013). Handbook of personality at work (applied psychology series). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, Y. P. (2023). A step-by-step guide PLS-SEM data analysis using SmartPLS 4. Researchtree Education. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, W. W. (1999). Biostatistics: A foundation for analysis in the health sciences (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, D., & Yang, L. (2012). Perceptions of auditor conscientiousness and fraud detection. Journal of Forensic & Investigative Accounting, 4(2), 110–141. [Google Scholar]

- Farag, M. S., & Elias, R. Z. (2012). The impact of accounting students’ professional skepticism on their ethical perception of earnings management. In Research on professional responsibility and ethics in accounting (pp. 185–200). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Faramarzi, A., Jamshidinavid, B., Ghanbari, M., & Mohammadi, S. (2022). Studying the effect of cultural models on the development of ethical behavior of accountants and auditors. International Journal of Finance & Managerial Accounting, 7(27), 291–310. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, D. R. (1980). A taxonomy of ethical ideologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(1), 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, C., & Murphy, P. (2015). The ties that bind: The decision toco-offend in fraud. Contemporary Accounting Research, 32(1), 18–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, R., & Durtschi, C. (2004). The effect of professional skepticism on the fraud detection skills of internal auditors. SSRN, 617062. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=617062 (accessed on 8 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, R. U., & Putri, S. A. A. (2018). The influence of the implementation of the code of ethics and professional skepticism of auditors on fraud detection at the BPKP representative office of north sumatra province. Liabilities (Jurnal Pendidikan Akuntansi), 1(3), 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R. (2019). The influence of professional ethics and auditor independence on fraud detection with auditor professionalism as a moderating variable. Jurnal Magister Akuntansi Trisakti, 6(2), 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, R., Wallage, P., & Gortemaker, H. (2014). Principles of auditing an introduction to international standard on auditing (3th ed.). Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F., & Simmel, M. (1944). An experimental study of apparent behavior. The American Journal of Psychology, 57(2), 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heliantono, H., Gunawan, I. D., Khomsiyah, K., & Arsjah, R. J. (2020). Moral development as the influencer of fraud detection. International Journal of Financial, Accounting, and Management, 2(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heni, H., Sayekti, Y., & Wardayati, S. M. (2020). New perspective: Measuring auditor professionalism in fraud detection. Wiga: Jurnal Penelitian Ilmu Ekonomi, 10(2), 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henle, C. A., Giacalone, R. A., & Jurkiewicz, C. L. (2005). The role of ethical ideology in workplace deviance. Journal of Business Ethics, 56, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G., & Hill, K. (2024). The people’s law dictionary: Legal dictionary. Available online: https://dictionary.law.com/Default.aspx?selected=785 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Hussin, S. A. H. S., Iskandar, T. M., Saleh, N. M., & Jaffar, R. (2017). Professional skepticism and auditors’ assessment of misstatement risks: The moderating effect of experience and time budget pressure. Economics & Sociology, 10(4), 225–250. [Google Scholar]

- Idawati, W. (2020). Analysis of fraud detection in financial reports. BAJ: Behavioral Accounting Journal, 3(1), 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Indrasti, A. W., & Karlina, B. (2020, March). Determinants affecting the auditor’s ability of fraud detection: Internal and external factors (empirical study at the public accounting firm in Tangerang and South Jakarta Region in 2019). In Annual international conference on accounting research (AICAR 2019) (pp. 19–22). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Federation of Accountants (IFAC): International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB). (2024). Proposed international standard on auditing 240 (revised): The auditor’s responsibilities relating to fraud in an audit of financial statements and proposed conforming and consequential amendments to other ISAs. IFAC. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, Q., & Ali Khan, S. M. F. (2024). Assessing consumer behavior in sustainable product markets: A structural equation modeling approach with partial least squares analysis. Sustainability, 16(8), 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, S., Hardies, K., Vanstraelen, A., & Zehms, K. M. (2021). Auditors’ professional skepticism: Traits, behavioral intentions, and actions. Behavioral Intentions, and Actions. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H. H. (1973). The processes of causal attribution. American Psychologist, 28(2), 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H. H., & Michela, J. L. (1980). Attribution theory and research. Annual Review of Psychology, 31(1), 457–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerler, W. A., & Killough, L. N. (2009). The effects of satisfaction with a client’s management during a prior audit engagement, trust, and moral reasoning on auditors’ perceived risk of management fraud. Journal of Business Ethics, 85, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, A. C., Creswell, J., Plano Clark, V. L., Smith, K. C., & Meissner, H. I. (2012). Best practices in mixed methods for quality of life research. Quality of life Research, 21, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques (2nd ed.). New Age International (P) Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Kusumastuti, R., Ghozali, I., & Fuad, F. (2016). Auditor professional commitment and performance: An ethical issue role. Risk Governance and Control Financial Markets & Institutions, 6(4), 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]