The Moderating Role of Finance, Accounting, and Digital Disruption in ESG, Financial Reporting, and Auditing: A Triple-Helix Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Hypotheses Development

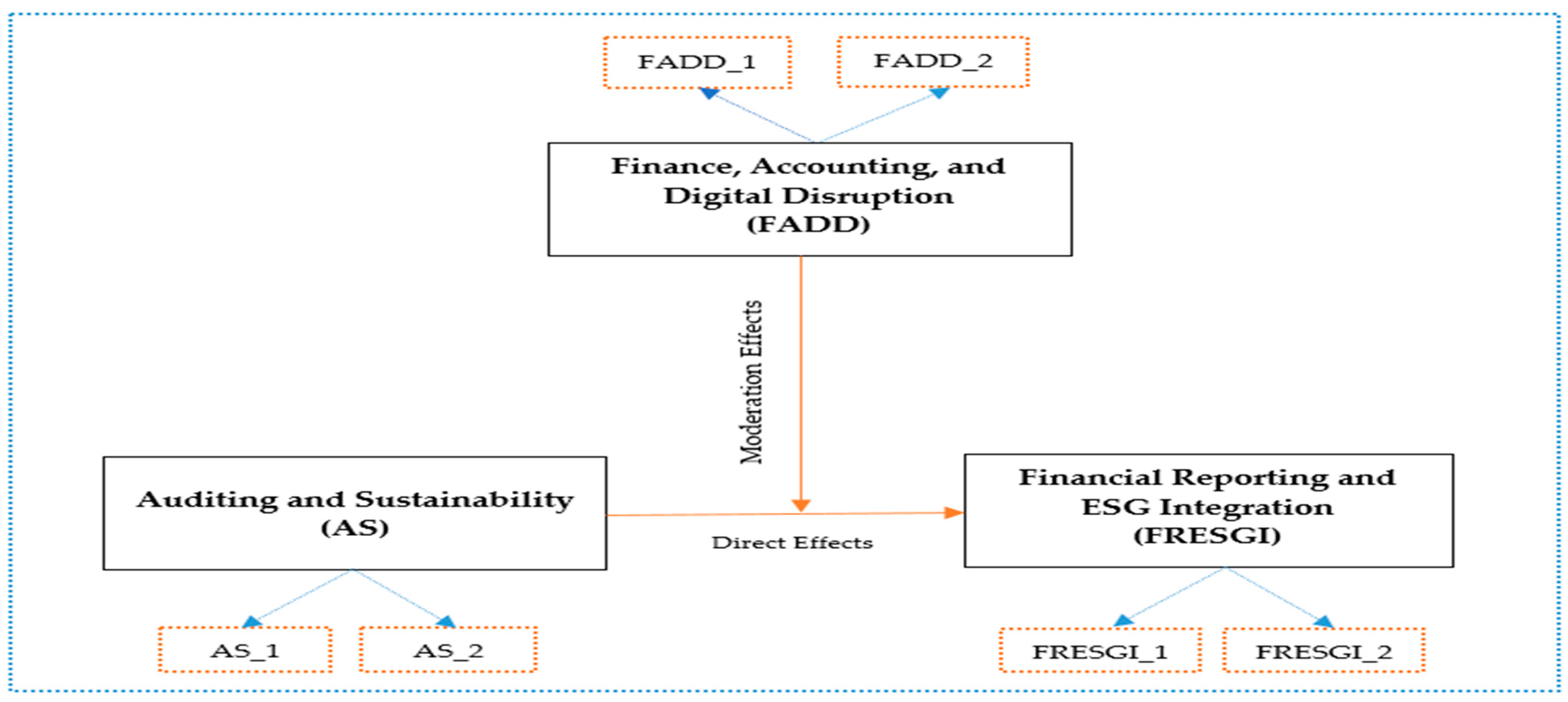

2.1.1. Direct Effects

2.1.2. Moderation Effects

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Purpose of This Paper

3.2. Survey Instrument Development

- ✓

- Expert review: Five academics and five industry practitioners reviewed the questionnaire for content validity, clarity, and relevance.

- ✓

- Pilot study: A small sample of 20 respondents participated in a pilot test. Based on their feedback, minor adjustments were made to item wording to enhance clarity and ensure respondent comprehension.

3.3. Sampling Procedure and Sample Size Justification

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Data Collection

3.6. Development and Validation of Key Constructs

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Practical Implications

6.2. Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdelwahed, N. A. A., Soomro, F. A., Bano, S., Aldoghan, M. A., Elrayah, M., & Soomro, B. A. (2025). Enabling sustainable futures: Examining organizational dynamics and technology platforms in digital transformation to achieve firm sustainability. International Journal of Innovation Science. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. M. A. (2023). The relationship between corporate governance mechanisms and integrated reporting practices and their impact on sustainable development goals: Evidence from South Africa. Meditari Accountancy Research, 31(6), 1919–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharasis, E. E. (2025). The implementation of IFRS electronic financial reporting—XBRL and usefulness of financial information: Evidence from Jordanian finance industry. International Journal of Law and Management. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almnadheh, Y., Samara, H., & AlQudah, M. Z. (2025). Enhancing ESG integration in corporate strategy: A bibliometric study and content analysis. International Journal of Law and Management. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsughayer, S. (2025). Role of ERP systems in management accounting in SMEs in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 21(2), 382–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H. M. G., Hassan, R. S., Ghoneim, H., & Abdallah, A. S. (2025). A bibliometric analysis of accounting education literature in the digital era: Current status, implications and agenda for future research. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 23(2), 742–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argento, D., Dobija, D., Grossi, G., Marrone, M., & Mora, L. (2025). The unaccounted effects of digital transformation: Implications for accounting, auditing and accountability research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdimetaj, E., Lulaj, E., & Alcoriza, G. B. (2025). Bridging theory to practice: Empowering indigenous businesses through innovative analysis of audited financial statements. In I. Ghosal, S. Gupta, S. Rana, & D. Saha (Eds.), Indigenous empowerment through human-machine interactions (pp. 35–52). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, M. M., & Zhang, J. H. (2025). Financial structure and innovation: Firm-level evidence from Africa. Asian Review of Accounting, 33(2), 189–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, R. (2025). Corporate sustainability reporting. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 49, 107280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J., & Larrinaga, C. (2024). The influence of Power’s audit society in environmental and sustainability accounting. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 21(1), 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhayoun, I., El Amrani, M., Barhdadi, A., & Azzaoui, W. (2025). Adoption of ISSB standards in emerging markets—Insights from Moroccan companies’ organizational readiness. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Harvard Business Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aquila, J. M. (1998). Is the control environment related to financial reporting decisions? Managerial Auditing Journal, 13(8), 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, P., Gunarathne, N., & Kumar, S. (2025). Exploring the impact of digital knowledge, integration and performance on sustainable accounting, reporting and assurance. Meditari Accountancy Research, 33(2), 497–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaif, A. R. (2025). Exploring the landscape of financial technology: Innovations, regulatory challenges and the disruptive impact of fintech on traditional financial services. In M. Shehadeh, & K. Hussainey (Eds.), From digital disruption to dominance (pp. 3–44). Technological Innovation and Sustainability for Business Competitive Advantage. Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulos, P. (2025). EU corporate sustainability performance and qualified audit opinion: The role of audit committee independence. Managerial Auditing Journal, 40(2), 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emblen-Perry, K. (2019). Can sustainability audits provide effective, hands-on business sustainability learning, teaching and assessment for business management undergraduates? International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 20(7), 1191–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emblen-Perry, K. (2022). Auditing a case study: Enhancing case-based learning in education for sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 381((Pt 1)), 134944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (1995). The Triple Helix—University-industry-government relations: A laboratory for knowledge based economic development. EASST Review, 14(1), 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Fauzel, S., Tandrayen-Ragoobur, V., & Matadeen, S. J. (2024). A literature survey of technological disruptions in the service sector. In R. P. Singh Kaurav, & V. Mishra (Eds.), Review of technologies and disruptive business strategies (Vol. 3, pp. 185–202). Review of Management Literature. Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdinands, R., Azam, S. M. F., & Khatibi, A. (2024). The work in progress of a developing nation’s Triple Helix and its impact on patent commercialization. The case of Sri Lanka. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 15(4), 839–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman. [Google Scholar]

- Galvao, A., Mascarenhas, C., Marques, C., Ferreira, J., & Ratten, V. (2019). Triple helix and its evolution: A systematic literature review. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 10(3), 812–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S. S., & Zhang, J. J. (2006). Stakeholder engagement, social auditing and corporate sustainability. Business Process Management Journal, 12(6), 722–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, J. L., Li, C., Liao, L., Yang, J., & Zhou, S. (2024). Audit firms’ corporate social responsibility activities and auditor reputation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 113, 101569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiew, L.-C., Lam, M.-T., & Ho, S.-J. (2025). Unveiling the nexus: Unravelling the dynamics of financial inclusion, FinTech adoption and societal sustainability in Malaysia. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 23(2), 575–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C., Mirza, S. S., Zhang, C., & Miao, Y. (2025). Corporate digital transformation and audit signals: Building trust in the digital age. Meditari Accountancy Research, 33(2), 553–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inder, S. (2023). Triple entry accounting with blockchain technology. In S. Grima, E. Thalassinos, G. G. Noja, T. V. Stamataopoulos, T. Vasiljeva, & T. Volkova (Eds.), Digital transformation, strategic resilience, cyber security and risk management (Vol. 111B, pp. 123–131). Contemporary Studies in Economic and Financial Analysis. Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, A. (2025). Sustainability committees’ influence on ESG controversies and sustainability assurance: A comparative study in polluting and non-polluting firms. Journal of Global Responsibility. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, I. (2024). From the Triple Helix model of innovations to the quantitative theory of meaning. Triple Helix, 10(2), 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaludin, A. F., Husain, M. F. H., & Razali, M. N. (2025). Assessing environmental, social and governance of property-listed companies in Malaysia. Property Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joreskog, K. G. (1969). A general approach to confirmatory maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 34(2), 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastrup, T., Grant, M., & Nilsson, F. (2025). Data analytics use in financial due diligence: The influence of accounting and commercial logic. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 22(2), 158–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A., Argento, D., Sharma, U., & Soobaroyen, T. (2025). “Everything, everywhere, all at once”: The role of accounting and reporting in achieving sustainable development goals. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 37(2), 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kukalaj, R., Lulaj, E., & Dragusha, B. (2025). Evaluating business performance through audited financial statements: Considerations for future trends in indigenous finance. In I. Ghosal, S. Gupta, S. Rana, & D. Saha (Eds.), Indigenous empowerment through human-machine interactions (pp. 133–151). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V., Verma, P., Mittal, A., Gupta, P., Raj, R., & Kaswan, M. S. (2024). Addressing the Kaizen business operations: The role of triple helix actors during COVID-19 outbreak. The TQM Journal, 36(6), 1665–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C. K., Ko, J., & Chen, X. (2025). Economic crises and the erosion of sustainability: A global analysis of ESG performance in 100 countries (1990–2019). Innovation and Green Development, 4(2), 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewa, E. M., Gatimbu, K. K., & Kariuki, P. W. (2025). Sustainability reporting in sub-Saharan Africa: Does audit committee diversity and executive compensation matter? Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 11, 101262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., & Han, Y. (2025). The unexpected effect of digital inclusive finance on enterprise resilience. Finance Research Letters, 78, 107148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Liu, Q., & Wei, Y. (2025). Digital finance, internal control, and audit quality. Finance Research Letters, 76, 107033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liudmyla, L., & Maria, K. (2022). Assessment of financial reporting quality: Theoretical background. In S. Grima, E. Özen, & H. Boz (Eds.), The new digital era: Other emerging risks and opportunities (Vol. 109B, pp. 141–150). Contemporary Studies in Economic and Financial Analysis. Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodhia, S., Farooq, M. B., Sharma, U., & Zaman, R. (2025). Digital technologies and sustainability accounting, reporting and assurance: Framework and research opportunities. Meditari Accountancy Research, 33(2), 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulaj, E. (2021). Quality and reflecting of financial position: An enterprises model through logisticregression and natural logarithm. Quality and reflecting of financial position: An enterprises model through logisticregression and natural logarithm. Journal of Economic Development, Environment and People, 10(1), 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulaj, E. (2023). A sustainable business profit through customers and its impacts on three key business domains: Technology, innovation, and service (TIS). Business, Management and Economics Engineering, 21(1), 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulaj, E. (2025a). Decoding the financial zeitgeist: A Scientific exploration of the calculus of capital for cost-efficient and sustainable growth in investments and operations. Brazilian Administration Review, 22(2), e230171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulaj, E. (2025b). Penny-wise acumen in costonomics: Transforming costs into entrepreneurial gold through smart financial management. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulaj, E., Dragusha, B., & Hysa, E. (2023). Investigating accounting factors through audited financial statements in businesses toward a circular economy: Why a sustainable profit through qualified staff and investment in technology? Administrative Sciences, 13(3), 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulaj, E., Dragusha, B., Hysa, E., & Voica, M. C. (2024a). Synergizing sustainability and financial prosperity: Unraveling the structure of business profit growth through consumer-centric strategies—The cases of Kosovo and Albania. International Journal of Financial Studies, 12(2), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulaj, E., Dragusha, B., & Lulaj, D. (2024b). Market mavericks in emerging economies: Redefining sales velocity and profit surge in today’s dynamic business environment. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(9), 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulaj, E., Gopalakrishnan, A., & Kehinde Lamidi, K. (2025). Financing and investing in women-led businesses: Understanding strategic profits and entrepreneurial expectations by analysing the factors that determine their company success. Periodica Polytechnica Social and Management Sciences, 33(1), 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulaj, E., Hysa, E., & Panait, M. (2024c). Does digitalization drive sustainable transformation in finance and accounting? Kybernetes. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulaj, E., & Iseni, E. (2018). Role of analysis CVP (Cost-Volume-Profit) as important indicator for planning and making decisions in the business environment. European Journal of Economics and Business Studies, 4(2), 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulaj, E., & Minguez-Vera, A. (2024). Cash flow dynamics: Amplifying swing models in a volatile economic climate for financial resilience and outcomes. Scientific Annals of Economics and Business, 71(3), 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulaj, E., Tahiraj, D., Hameed, A. A., & Lulaj, D. (2024d, September 7–8). Seeing isn’t always believing: Unveiling the financial risks of fraudulent images on personal finances in online shopping. 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Blockchain, and Internet of Things (AIBThings) (pp. 1–10), Mt Pleasant, MI, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahsina, M., Agustia, D., Nasution, D., & Dianawati, W. (2025). The mediating role of risk management in the relationship between audit committee effectiveness and firm sustainability performance. Corporate Governance, 25(3), 534–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mêgnigbêto, E. (2024). Convexity of the triple helix of innovation game. International Journal of Innovation Science. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouazen, A. M., Hernández-Lara, A. B., Chahine, J., & Halawi, A. (2025). Triple bottom line sustainability and Innovation 5.0 management through the lens of Industry 5.0, Society 5.0 and Digitized Value Chain 5.0. European Journal of Innovation Management. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muaaz, H., & Ali, M. (2024). Sustainability and ESG Integration. In M. Ali, L. Choi-Meng, C.-H. Puah, S. A. Raza, & P. Sivanandan (Eds.), Strategic financial management (pp. 13–33). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, K., Farooq, M. B., Zahir-Ul-Hassan, M. K., & Rauf, F. (2025). AI adoption, ESG disclosure quality and sustainability committee heterogeneity: Evidence from Chinese companies. Meditari Accountancy Research, 33(2), 708–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N. M., Abu Afifa, M. M., Thi Truc Dao, V., Van Bui, D., & Vo Van, H. (2025). Leveraging artificial intelligence and blockchain in accounting to boost ESG performance: The role of risk management and environmental uncertainty. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T., Le-Anh, T., Nguyen Thi Hong, N., Huong Nguyen, L. T., & Nguyen Xuan, T. (2025). Digital transformation in accounting of Vietnamese small and medium enterprises. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 23(2), 769–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). The assessment of reliability. Psychometric Theory, 3, 248–292. [Google Scholar]

- Oyinlola, B. (2025). Do CEO and board characteristics matter in the ESG performance of their firms? Corporate Governance, 25(8), 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Domínguez, J., Sanz Martín, L., López Pérez, G., & Zafra Gómez, J. L. (2025). The disruption of blockchain technology in accounting: A review of scientific progress. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumphrey, L. D., & Crain, G. (2008). Do the existing financial reporting and auditor reporting standards adequately protect the public interest? A case study. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 20(3), 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W., Dissanayake, D., Leong, S., Kuruppu, S., & Tilt, C. (2025). Sustainability reporting in Indo-Pacific countries: An integrative response to local and global frameworks. Meditari Accountancy Research, 33(7), 157–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, R., Vasishta, P., Singla, A., & Tanwar, N. (2025). Mapping ESG and CSR literature: A bibliometric study of research trends and emerging themes. International Journal of Law and Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Barbadillo, E., & Martínez-Ferrero, J. (2022). The choice of incumbent financial auditors to provide sustainability assurance and audit services from a legitimacy perspective. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 13(2), 459–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, N., & Kharb, R. (2025). Strategic enablers for ESG adoption: A modified TISM perspective. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schebesch, K. B., ȘSoim, H. F., & Blaga, R. L. (2024). The triple-helix model as foundation of innovative entrepreneurial ecosystems. Journal of Ethics in Entrepreneurship and Technology, 4(2), 104–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, C. (1927). The abilities of man. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, S. G. (2010). The fundamental role of technology in accounting: Researching reality. In V. Arnold (Ed.), Advances in accounting behavioral research (Vol. 13, pp. 1–11). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauseef, S., & Khurshid, A. A. (2025). ESG disclosure, ranking and firm’s characteristics: Evidence from Pakistan. South Asian Journal of Business Studies. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R., AlSaleh, D., & Hale, D. (2023). Digital disruption: A manager’s eye view. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 38(1), 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twesigye, M., Obedgiu, V., Nkurunziza, G., & Oceng, P. (2025). The mediating role of stewardship behaviour on leadership competencies and sustainability of government projects in developing economies. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, U. H., Baita, A. J., Hamadou, I., & Abduh, M. (2025). Digital finance and SME financial inclusion in Africa. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 16(1), 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, O., & Calvo, N. (2015). From the Triple Helix model to the global open innovation model: A case study based on international cooperation for innovation in Dominican Republic. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 35, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawak, S., Teixeira Domingues, J. P., & Sampaio, P. (2024). Quality 4.0 in higher education: Reinventing academic-industry-government collaboration during disruptive times. The TQM Journal, 36(6), 1569–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R. F., Meserve, R. J., & Stanovich, K. E. (2012). Cognitive sophistication does not attenuate the bias blind spot. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(3), 506–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcı, A. M. (2023). The Quintuple Helix, Industrial 5.0, and Society 5.0. In B. Akkaya, S. A. Apostu, E. Hysa, & M. Panait (Eds.), Digitalization, sustainable development, and Industry 5.0 (pp. 317–336). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Zhang, L., Wang, S., & Zhang, D. (2025). Firm digitalization and inter-firm financing along the supply chain. Economic Analysis and Policy, 86, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C. (2011). The future roles of STPs in green growth of China: Based on the public-university-industry triple helix for sustainable development. Journal of Knowledge-Based Innovation in China, 3(3), 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimand-Sheiner, D., & Earon, A. (2019). Disruptions of account planning in the digital age. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 37(2), 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Role | Interaction | Equation | Moderates | Outcome | Theories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auditing and Sustainability (AS) Financial Reporting and ESG Integration (FRESGI) Finance, Accounting, and Digital Disruption (FADD) | IV DV Mod. | Interaction 1 Interaction 2 Interaction 3 Interaction 4 | (AS_1 × FADD_1) (AS_1 × FADD_2) (AS_2 × FADD_1) (AS_2 × FADD_2) | H3a, H3b H3c, H3d H3e, H3f H3g, H3h | FRESGI_2, FRESGI_1 FRESGI_2, FRESGI_1 FRESGI_2, FRESGI_1 FRESGI_2, FRESGI_1 | Triple-Helix Model of Innovation (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 1995) Stakeholder Theory (Freeman, 1984) Legitimacy Theory-Suchman (1995) Agency Theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1976) Signaling Theory (Spence, 1973) Theory of Disruptive Innovation (Christensen, 1997) Institutional Theory (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) |

| Factor 1 Auditing and Sustainability (AS) | ||

| Subfactor 1: Corporate Perspective (ASCP) | ||

| Item | Constructs | Source |

| AS1 | Auditing helps corporates implement fair labor policies and uphold decent work conditions. | Emblen-Perry (2019) Lulaj (2025b) Pumphrey and Crain (2008) Kukalaj et al. (2025) Lulaj et al. (2024b) Avdimetaj et al. (2025) Ruiz-Barbadillo and Martínez-Ferrero (2022) Lulaj et al. (2024a) Gao and Zhang (2006) |

| AS2 | Strong internal auditing practices improve corporate governance, sustainability accountability, and risk management. | |

| AS3 | The digital transformation of auditing (AI, blockchain, automation) enhances transparency, efficiency, and fraud detection. | |

| AS4 | Independent auditing helps detect and prevent financial misstatements, fraud, and ESG violations. | |

| AS5 | Ethical and sustainable auditing practices drive long-term economic growth and responsible business conduct. | |

| Subfactor 2: Government and Academia Perspectives (ASGAP) | ||

| AS6 | Government regulations play a critical role in ensuring ethical, transparent, and sustainable auditing practices. | |

| AS7 | Auditing contributes to financial stability and reduces the risk of economic and labor market crises. | |

| AS8 | Public sector audits strengthen fiscal accountability, ensuring effective use of resources for economic development. | |

| AS9 | Auditing standards should evolve to integrate ESG (environmental, social, and governance) factors into financial oversight. | |

| AS10 | Collaborations between corporates, the government, and academia advance research and innovation in sustainable auditing. | |

| Factor 2 Financial Reporting and ESG Integration (FRESGI) | ||

| Subfactor 1: Corporate Perspective (FRESGICP) | De Silva et al. (2025) N. M. Nguyen et al. (2025) Rani et al. (2025) Jamaludin et al. (2025) Liudmyla and Maria (2022) D’Aquila (1998) | |

| FRESGI1 | Transparent financial reporting enhances investor confidence and supports sustainable economic growth. | |

| FRESGI2 | Real-time and digital financial reporting systems improve decision-making and risk assessment. | |

| FRESGI3 | Reliable and verifiable financial statements improve corporate creditworthiness and long-term financial stability. | |

| FRESGI4 | Corporate fiscal transparency enhances responsible governance, risk management, and equitable economic policies. | |

| FRESGI5 | The integration of sustainability metrics into financial reports supports long-term business profitability and economic resilience. | |

| Subfactor 2: Government and Academia Perspectives (FRESGIGAP) | ||

| FRESGI6 | ESG and sustainability disclosures should be mandatory for corporate reporting and investor decision-making. | |

| FRESGI7 | International financial reporting standards (IFRS) improve global trade, cross-border investments, and sustainability compliance. | |

| FRESGI8 | Third-party verification of financial and ESG reports enhances corporate credibility and stakeholder trust. | |

| FRESGI9 | Effective financial reporting reduces economic inequality by promoting fair wages, job creation, and inclusive growth. | |

| FRESGI10 | The use of AI and blockchain in financial reporting has increased accuracy, efficiency, and fraud prevention. | |

| Factor 3 Finance, Accounting, and Digital Disruption (FADD) | ||

| Subfactor 1: Corporate Perspective (FADDCP) | Lulaj et al. (2024c) Thakur et al. (2023) Zimand-Sheiner and Earon (2019) Lulaj (2021) Fauzel et al. (2024) Wawak et al. (2024) Ayalew and Zhang (2025) Alsughayer (2025) Hiew et al. (2025) Lulaj and Iseni (2018). Sutton (2010) Inder (2023) | |

| FADD1 | Responsible financial management is essential for corporate sustainability, job security, and economic stability. | |

| FADD2 | The adoption of fintech (AI, blockchain, digital banking) expands financial accessibility and promotes economic participation. | |

| FADD3 | Corporate financial planning and responsible investment strategies drive sustainable national economic development. | |

| FADD4 | Ethical financial decision-making supports fair employment, decent wages, and long-term job creation. | |

| FADD5 | Investment in human capital strengthens financial stability, innovation, and sustainable business growth. | |

| Subfactor 2: Government and Academia Perspectives (FADDGAP) | ||

| FADD6 | Risk management strategies, including ESG risk assessment, are crucial for corporate resilience in uncertain economic environments. | |

| FADD7 | Corporate financial policies and tax strategies influence employment, wages, and sustainable business growth. | |

| FADD8 | Corporate financial regulations should align with sustainability goals, responsible investments, and green financing. | |

| FADD9 | Access to financial education and digital literacy enhances workforce productivity and financial inclusion. | |

| FADD10 | Accounting innovations, including automation and AI-driven analytics, improve corporate financial decision-making and sustainability reporting. | |

| Category | Variable | Freq. | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gen. | G A C | Male | 100 | 50.0 |

| Female | 78 | 39.0 | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 22 | 11.0 | ||

| Age | G A C | 18–25 years | 12 | 6.0 |

| 26–35 years | 65 | 32.5 | ||

| 36–45 years | 64 | 32.0 | ||

| 46–55 years | 36 | 18.0 | ||

| Over 56 years | 23 | 11.5 | ||

| Edu. | G A C | Bachelor’s degree | 76 | 38.0 |

| Master’s degree | 91 | 45.5 | ||

| PhD | 33 | 16.5 | ||

| Pos. | G | Ministry Official (ME, MFLT) | 2 | 1.0 |

| A | Academic Staff | 33 | 16.5 | |

C | Financial Manager | 27 | 13.5 | |

| General Manager | 38 | 19.0 | ||

| Accountant | 50 | 25.0 | ||

| Business Owner | 21 | 10.5 | ||

| Internal Auditor | 15 | 7.5 | ||

| Director | 14 | 7.0 | ||

| WE | G A C | 1–5 years | 10 | 5.0 |

| 6–10 years | 91 | 45.5 | ||

| Over 10 years | 99 | 49.5 | ||

| ES | G A C | Public | 33 | 16.5 |

| Private | 167 | 83.5 | ||

| DIAD | G A C | Yes | 195 | 97.5 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Don’t know | 5 | 2.5 | ||

| CPFRS | G A C | Yes | 199 | 99.5 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Don’t know | 1 | 0.5 | ||

| UATFMA | G A C | Yes | 191 | 95.5 |

| No | 2 | 1.0 | ||

| Don’t know | 7 | 3.5 | ||

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Gen. | Age. | Edu. | Pos. | WE | ES | AS | FRESGI | FADD | DIAD | CPFRS | UATEMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gen | 1.61 | 0.69 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Age | 2.97 | 1.11 | −0.01 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Edu | 2.79 | 0.71 | −0.06 | −0.10 | 1 | |||||||||

| Pos. | 4.64 | 2.03 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.15 * | 1 | ||||||||

| WE | 2.46 | 0.60 | −0.00 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 1 | |||||||

| ES | 1.84 | 0.37 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.13 | −0.10 | 1 | ||||||

| AS | 4.34 | 0.39 | −0.13 | −0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.10 | 0.08 | 1 | |||||

| FRESGI | 4.31 | 0.37 | −0.10 | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.03 | −0.10 | 0.10 | 0.88 ** | 1 | ||||

| FADD | 4.31 | 0.38 | −0.12 | −0.13 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.81 ** | 0.85 ** | 1 | |||

| DIAD | 1.05 | 0.31 | −0.10 | 0.18 * | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.00 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 1 | ||

| CPFRS | 1.01 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.16 * | −0.11 | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 1 | |

| UATFMA | 1.08 | 0.38 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.11 | −0.05 | −0.18 * | −0.17 * | −0.19 ** | 0.05 | −0.02 | 1 |

| Component Matrix | KMO | TVE | α | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Subfactors | AS | FADD | FRESGI | |||

| AS_1 | AS1 | 0.99 | 0.74 | 0.88 | |||

| AS2 | 0.80 | ||||||

| AS3 | 0.78 | ||||||

| AS4 | 0.73 | ||||||

| AS5 | 0.79 | ||||||

| AS_2 | AS6 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 54.67 | 0.79 | ||

| AS7 | 0.73 | ||||||

| AS8 | 0.74 | ||||||

| AS9 | 0.67 | ||||||

| AS10 | 0.81 | ||||||

| FADD_1 | FADD1 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 53.04 | 0.78 | ||

| FADD2 | 0.75 | ||||||

| FADD3 | 0.73 | ||||||

| FADD4 | 0.75 | ||||||

| FADD5 | 0.68 | ||||||

| FADD_2 | FADD6 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 56.68 | 0.81 | ||

| FADD7 | 0.80 | ||||||

| FADD8 | 0.70 | ||||||

| FADD9 | 0.75 | ||||||

| FADD10 | 0.78 | ||||||

| FRESGI_1 | FRESGI1 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 52.10 | 0.77 | ||

| FRESGI2 | 0.72 | ||||||

| FRESGI3 | 0.75 | ||||||

| FRESGI4 | 0.68 | ||||||

| FRESGI5 | 0.66 | ||||||

| FRESGI_2 | FRESGI6 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 55.29 | 0.80 | ||

| FRESGI7 | 0.83 | ||||||

| FRESGI8 | 0.76 | ||||||

| FRESGI9 | 0.57 | ||||||

| FRESGI10 | 0.75 | ||||||

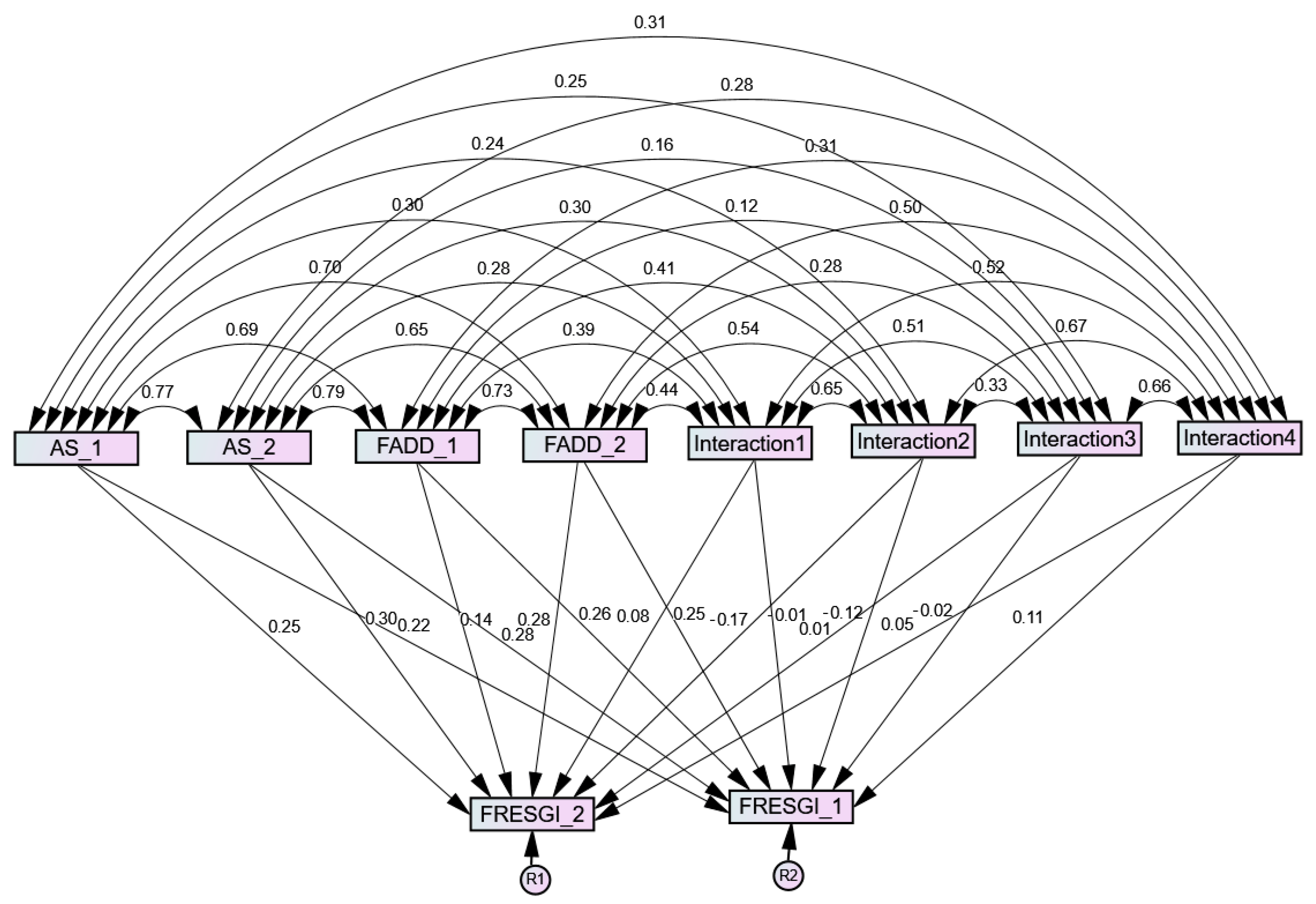

| Path | B | β | S.E. | C.R. | p-Value | Direct Effects | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FADD → FRESGI | 0.401 | 0.401 | 0.050 | 7.958 | *** | 0.013 | Highly Significant (p < 0.001) |

| AS → FRESGI | 0.553 | 0.553 | 0.050 | 10.970 | *** | 0.009 | Highly Significant (p < 0.001) |

| Path | B | β | S.E. | C.R. | p-Value | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FADD_2 → FRESGI_2 | 0.281 | 0.281 | 0.067 | 4.181 | *** | Highly Significant (p < 0.001) |

| FADD_1 → FRESGI_2 | 0.143 | 0.143 | 0.071 | 2.025 | 0.043 | Significant (p < 0.05) |

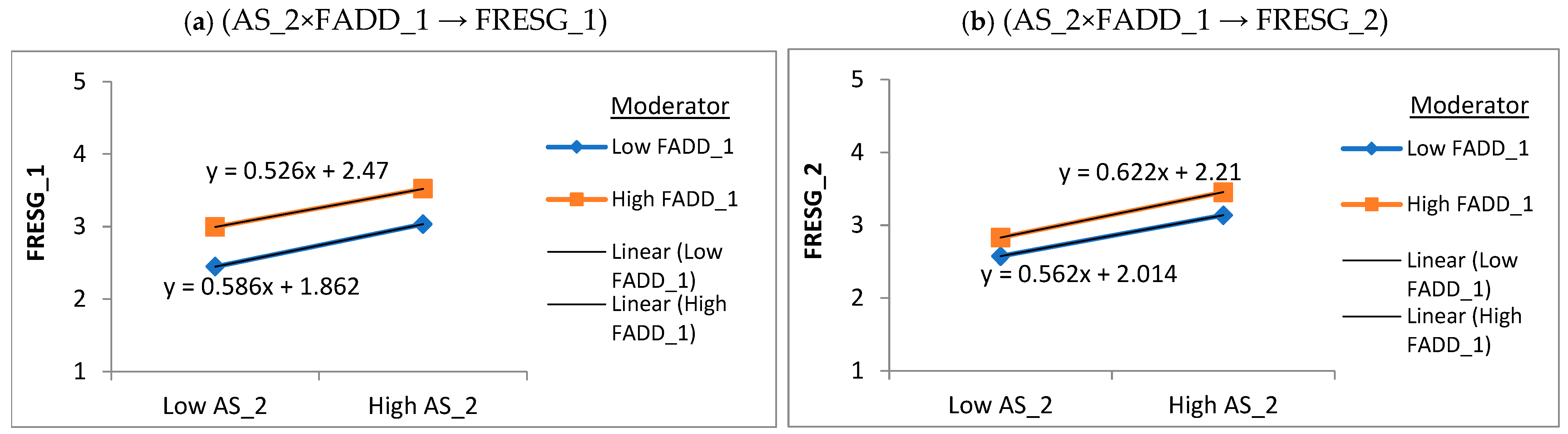

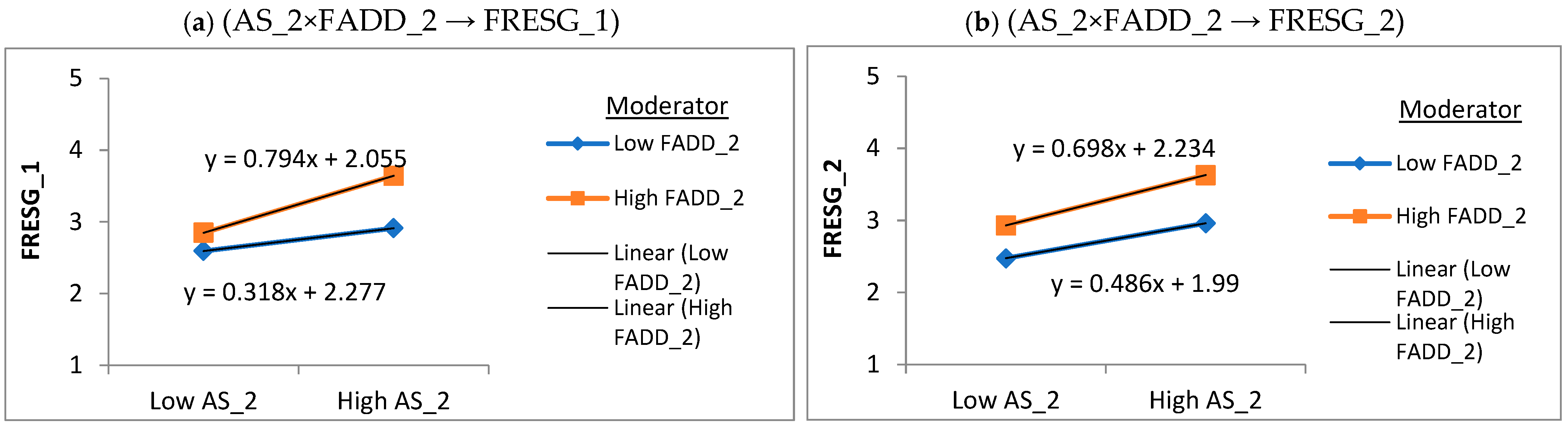

| AS_2 → FRESGI_2 | 0.296 | 0.296 | 0.070 | 4.242 | *** | Highly Significant (p < 0.001) |

| AS_1 → FRESGI_2 | 0.252 | 0.252 | 0.066 | 3.822 | *** | Highly Significant (p < 0.001) |

| Interaction1 → FRESGI_2 | 0.090 | 0.080 | 0.063 | 1.428 | 0.153 | Not Significant (p > 0.05) |

| Interaction1 → FRESGI_1 | −0.016 | −0.014 | 0.058 | −0.276 | 0.783 | Not Significant (p > 0.05) |

| Interaction2 → FRESGI_2 | −0.179 | −0.170 | 0.069 | −2.600 | 0.009 | Significant (p < 0.01) |

| Interaction3 → FRESGI_2 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.057 | 0.257 | 0.797 | Not Significant (p > 0.05) |

| Interaction4 → FRESGI_2 | 0.053 | 0.048 | 0.073 | 0.725 | 0.468 | Not Significant (p > 0.05) |

| FADD_2 → FRESGI_1 | 0.246 | 0.246 | 0.062 | 3.979 | *** | Highly Significant (p < 0.001) |

| FADD_1 → FRESGI_1 | 0.259 | 0.259 | 0.065 | 3.990 | *** | Highly Significant (p < 0.001) |

| AS_2 → FRESGI_1 | 0.278 | 0.278 | 0.064 | 4.342 | *** | Highly Significant (p < 0.001) |

| AS_1 → FRESGI_1 | 0.218 | 0.218 | 0.061 | 3.606 | *** | Highly Significant (p < 0.001) |

| Interaction2 → FRESGI_1 | −0.125 | −0.118 | 0.063 | −1.970 | 0.049 | Significant (p < 0.05) |

| Interaction3 → FRESGI_1 | −0.015 | −0.015 | 0.052 | −0.297 | 0.767 | Not Significant (p > 0.05) |

| Interaction4 → FRESGI_1 | 0.119 | 0.108 | 0.067 | 1.779 | 0.075 | Not Significant (p > 0.05) |

| Path | Estimate | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| AS_2 ↔ AS_1 | 0.766 | Strong positive correlation |

| AS_1 ↔ FADD_1 | 0.686 | Strong positive correlation |

| AS_1 ↔ FADD_2 | 0.703 | Strong positive correlation |

| AS_1 ↔ Interaction1 | 0.296 | Moderate positive correlation |

| AS_1 ↔ Interaction2 | 0.237 | Moderate positive correlation |

| AS_1 ↔ Interaction3 | 0.249 | Moderate positive correlation |

| AS_1 ↔ Interaction4 | 0.307 | Moderate positive correlation |

| AS_2 ↔ FADD_1 | 0.790 | Very strong positive correlation |

| AS_2 ↔ FADD_2 | 0.652 | Strong positive correlation |

| AS_2 ↔ Interaction1 | 0.281 | Moderate positive correlation |

| AS_2 ↔ Interaction2 | 0.295 | Moderate positive correlation |

| AS_2 ↔ Interaction3 | 0.163 | Weak positive correlation |

| AS_2 ↔ Interaction4 | 0.276 | Moderate positive correlation |

| FADD_1 ↔ FADD_2 | 0.731 | Strong positive correlation |

| FADD_1 ↔ Interaction1 | 0.394 | Moderate positive correlation |

| FADD_1 ↔ Interaction2 | 0.410 | Moderate positive correlation |

| FADD_1 ↔ Interaction3 | 0.123 | Weak positive correlation |

| FADD_1 ↔ Interaction4 | 0.309 | Moderate positive correlation |

| FADD_2 ↔ Interaction1 | 0.438 | Moderate positive correlation |

| FADD_2 ↔ Interaction2 | 0.544 | Moderate to strong positive correlation |

| FADD_2 ↔ Interaction3 | 0.282 | Moderate positive correlation |

| FADD_2 ↔ Interaction4 | 0.498 | Moderate positive correlation |

| Interaction1 ↔ Interaction2 | 0.655 | Strong positive correlation |

| Interaction1 ↔ Interaction3 | 0.511 | Moderate to strong positive correlation |

| Interaction1 ↔ Interaction4 | 0.520 | Moderate to strong positive correlation |

| Interaction2 ↔ Interaction3 | 0.329 | Moderate positive correlation |

| Interaction2 ↔ Interaction4 | 0.672 | Strong positive correlation |

| Interaction3 ↔ Interaction4 | 0.664 | Strong positive correlation |

| Variable | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS_2 | 0.995 | 0.100 | 9.975 | *** | Significant |

| AS_1 | 0.995 | 0.100 | 9.975 | *** | Significant |

| FADD_1 | 0.995 | 0.100 | 9.975 | *** | Significant |

| FADD_2 | 0.995 | 0.100 | 9.975 | *** | Significant |

| Interaction1 | 0.781 | 0.078 | 9.975 | *** | Significant |

| Interaction2 | 0.890 | 0.089 | 9.975 | *** | Significant |

| Interaction3 | 0.991 | 0.099 | 9.975 | *** | Significant |

| Interaction4 | 0.822 | 0.082 | 9.975 | *** | Significant |

| Test | Value | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMR | 0.007 | <0.05 | Good fit |

| GFI | 0.992 | >0.90 | Excellent fit |

| NFI | 0.995 | >0.90 | Excellent fit |

| CFI | 0.995 | >0.90 | Excellent fit |

| Hypothesis | Path | Supported/Not Supported | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | |||

| H1 (Effect of FADD on FRESGI) | FADD → FRESGI | Supported (p = 0.013) | |

| H1a | FADD_1 → FRESGI_2 | Supported (p = 0.043) | |

| H1b | FADD_2 → FRESGI_2 | Supported (p < 0.001) | |

| H1c | FADD_1 → FRESGI_1 | Supported (p < 0.001) | |

| H1d | FADD_2 → FRESGI_1 | Supported (p < 0.001) | |

| H2 (Effect of AS on FRESGI) | AS → FRESGI | Supported (p = 0.009) | |

| H2a | AS_1 → FRESGI_2 | Supported (p < 0.001) | |

| H2b | AS_2 → FRESGI_2 | Supported (p < 0.001) | |

| H2c | AS_1 → FRESGI_1 | Supported (p < 0.001) | |

| H2d | AS_2 → FRESGI_1 | Supported (p < 0.001) | |

| Moderation Effects | |||

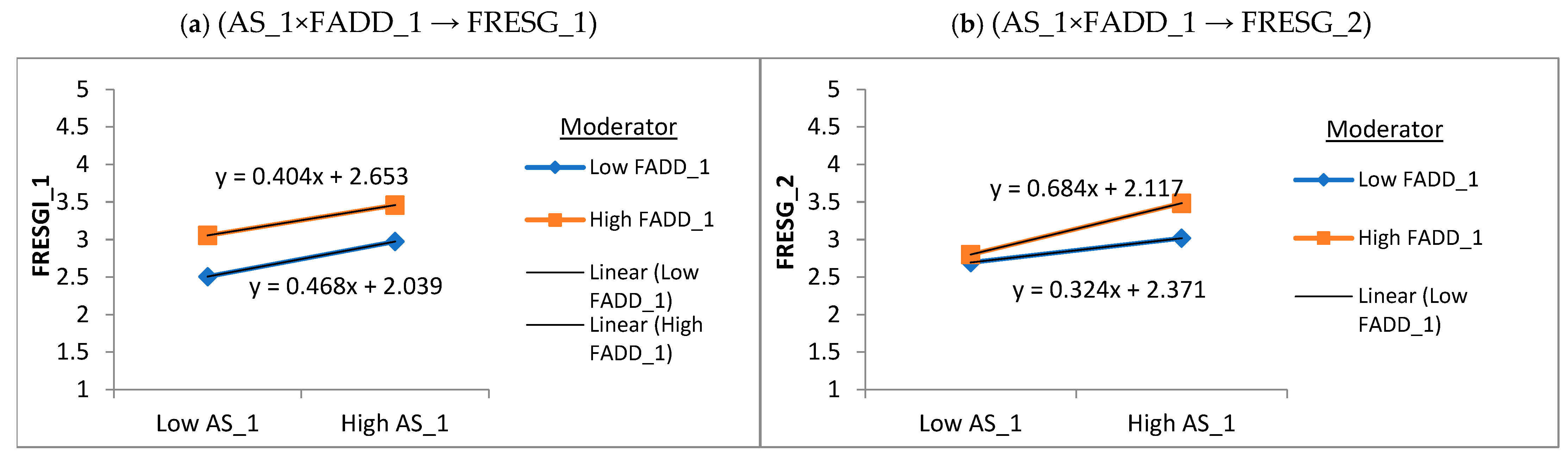

| H3a | Interaction1 | (AS_1 × FADD_1) → FRESGI_2 | Not Supported (p = 0.153) |

| H3b | (AS_1 × FADD_1) → FRESGI_1 | Not Supported (p = 0.783) | |

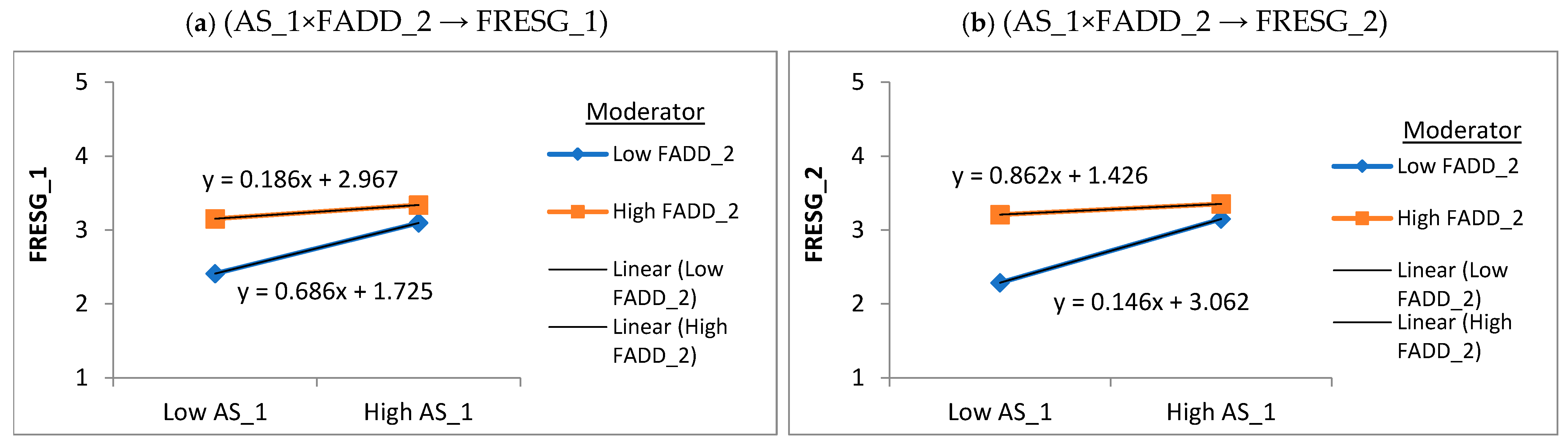

| H3c | Interaction2 | (AS_1 × FADD_2) → FRESGI_2 | Supported (Negative Moderation) (p = 0.009) |

| H3d | (AS_1 × FADD_2) → FRESGI_1 | Supported (Negative Moderation) (p = 0.049) | |

| H3e | Interaction3 | (AS_2 × FADD_1) → FRESGI_2 | Not Supported (p = 0.797) |

| H3f | (AS_2 × FADD_1) → FRESGI_1 | Not Supported (p = 0.767) | |

| H3g | Interaction4 | (AS_2 × FADD_2) → FRESGI_2 | Not Supported (p = 0.468) |

| H3h | (AS_2 × FADD_2) → FRESGI_1 | Not Supported (p = 0.075) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lulaj, E.; Brajković, M. The Moderating Role of Finance, Accounting, and Digital Disruption in ESG, Financial Reporting, and Auditing: A Triple-Helix Perspective. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050245

Lulaj E, Brajković M. The Moderating Role of Finance, Accounting, and Digital Disruption in ESG, Financial Reporting, and Auditing: A Triple-Helix Perspective. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(5):245. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050245

Chicago/Turabian StyleLulaj, Enkeleda, and Mileta Brajković. 2025. "The Moderating Role of Finance, Accounting, and Digital Disruption in ESG, Financial Reporting, and Auditing: A Triple-Helix Perspective" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 5: 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050245

APA StyleLulaj, E., & Brajković, M. (2025). The Moderating Role of Finance, Accounting, and Digital Disruption in ESG, Financial Reporting, and Auditing: A Triple-Helix Perspective. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(5), 245. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050245