Exploring Antecedents of Rural Users’ Continuance of Use Intention Toward Mobile Financial Services in Bangladesh: Deployment of Expectation Confirmation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

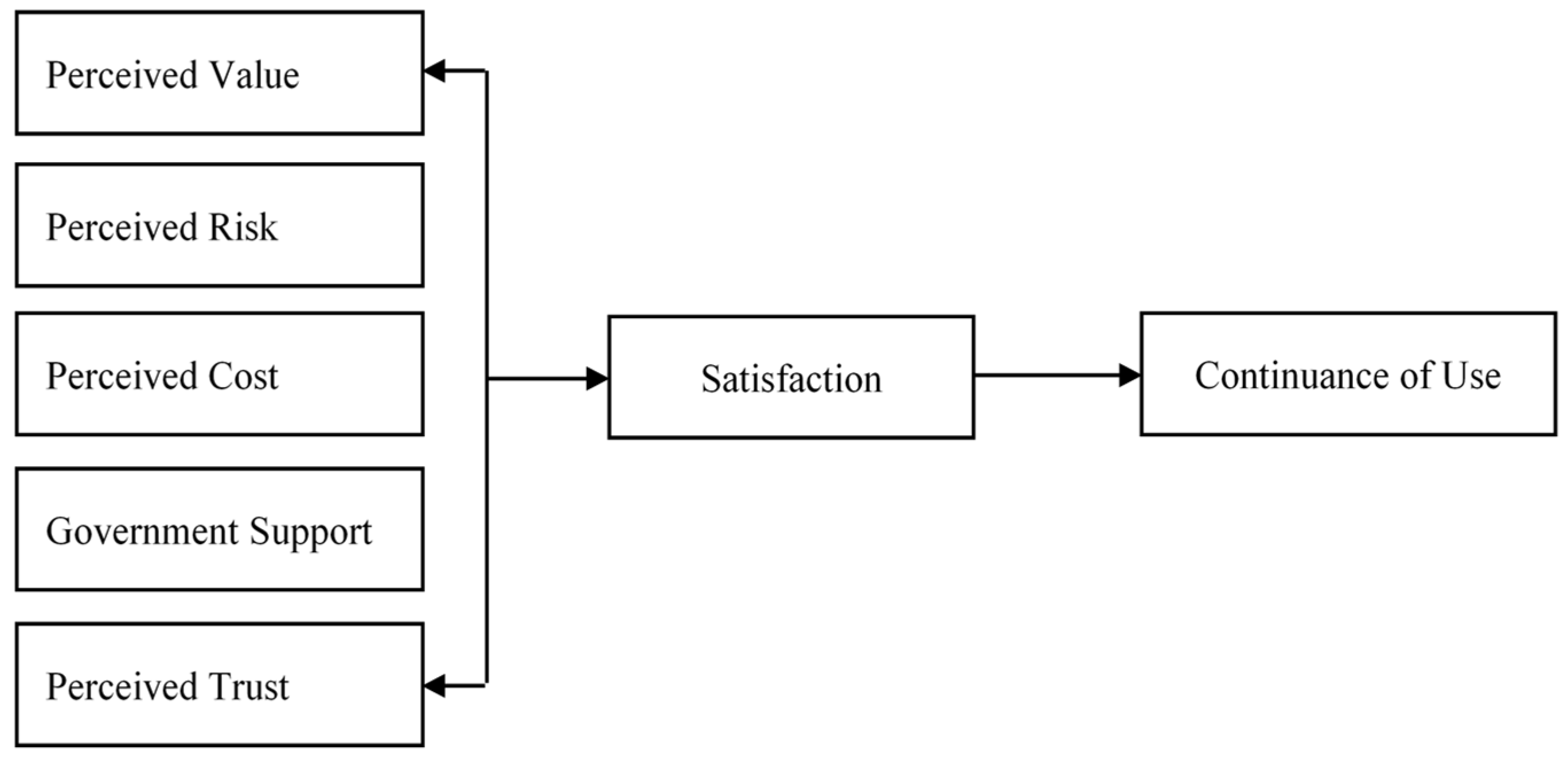

- I.

- To explore the significant determinants of satisfaction in a rural MFS context;

- II.

- To investigate the impact of satisfaction on the continuance of the use of MFS.

2. Literature Review

Expectation Confirmation Theory (ECM)

3. Hypothesis Developments

3.1. Perceived Value

3.2. Perceived Risk

3.3. Perceived Cost

3.4. Government Support

3.5. Perceived Trust

3.6. Satisfaction

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Context

4.2. Questionnaire Design

4.3. Sampling and Data Collection

4.4. Analysis and Findings

5. Results

5.1. Common Method Variance (CMV)

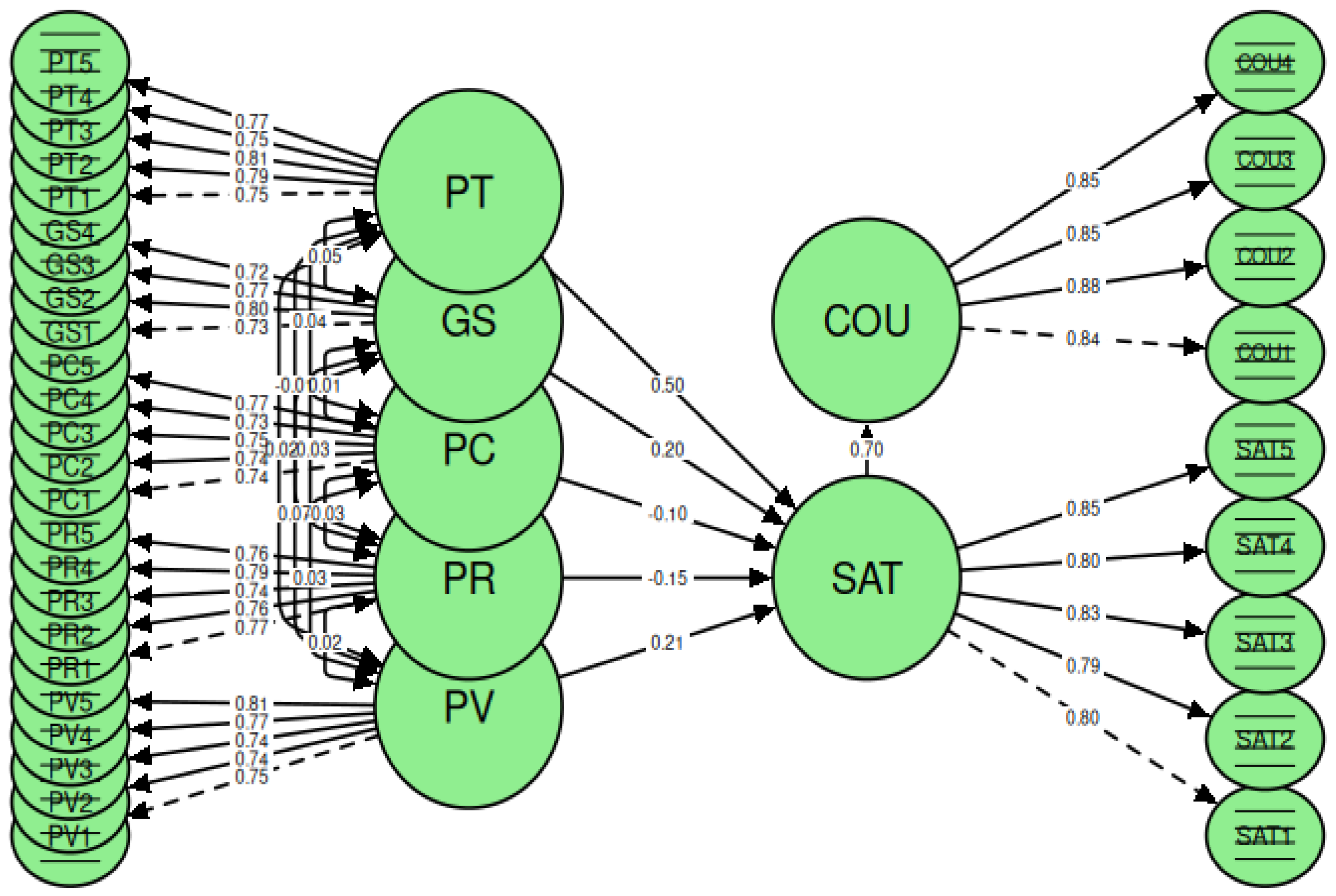

5.2. Measurement Model

5.2.1. Convergent Validity

5.2.2. Discriminant Validity

5.3. Structural Model

5.3.1. Multicollinearity

5.3.2. Hypothesis Testing

5.3.3. Effect Size, Standard Errors, and Confidence Intervals

5.3.4. Model Fit Indices

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Implications

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akter, M. S., Islam Bhuiyan, M. R., Tabassum, S. S. M. A. A., Uddin Milon, M. N., & Hoque, M. R. (2023). Factors affecting continuance intention to use E-wallet among university students in Bangladesh. International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technology, 71(6), 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amin, M., Muzareba, A. M., Chowdhury, I. U., & Khondkar, M. (2023). Understanding e-satisfaction, continuance intention, and e-loyalty toward mobile payment application during COVID-19: An investigation using the electronic technology continuance model. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 29(2), 318–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, Z., Amin, M. I., & Khan, M. S. A. (2019). Assessment of factors contributing to adoption of mobile financial services: A perspective of Bangladesh. Journal of Business Administration, 40(2), 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Balaskas, S., Koutroumani, M., Komis, K., & Rigou, M. (2024). FinTech services adoption in greece: The Roles of trust, government support, and technology acceptance factors. FinTech, 3(1), 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangladesh Bank. (2022). Bangladesh Mobile Financial Services (MFS) regulations, 2022. Payment Systems Department (PSD), Central Bank of Bangladesh. Available online: https://www.bb.org.bd/mediaroom/circulars/psd/feb152022psd04e.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Bangladesh Bank. (2024). Mobile Financial Services (MFS) comparative summary statement of September, 2024 and October, 2024. Payment Systems Department (PSD), Central Bank of Bangladesh. Available online: https://www.bb.org.bd/en/index.php/financialactivity/mfsdata (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. (2024). Report on socio-economic and demographic survey 2023. Statistics & Informatics Division (SID), Ministry of Planning, Bangladesh. Available online: http://nsds.bbs.gov.bd/storage/files/1/SEDS_2023_Report.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Quarterly, 25(3), 351–370. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3250921 (accessed on 15 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological methods & research, 21(2), 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dass, R., & Pal, S. (2011). Exploring the factors affecting the adoption of mobile financial services among the rural under-banked. ECIS 2011 Proceedings, 246. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2011/246/ (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Davis, F. D. (1986). A technology acceptance model for testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results. Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- De Mariz, F. (2022). Finance with a Purpose: FinTech, development and financial inclusion in the global economy. In Transformations in banking, finance and regulation. World Scientific. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J. (2015). Applied regression analysis and generalized linear models. Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Franque, F. B., Oliveira, T., Tam, C., & de Oliveira Santini, F. (2020). A meta-analysis of the quantitative studies in continuance intention to use an information system. Internet Research, 31(1), 123–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbongli, K., Xu, Y., Amedjonekou, K. M., & Kovács, L. (2020). Evaluation and classification of mobile financial services sustainability using structural equation modeling and multiple criteria decision-making methods. Sustainability, 12(4), 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geebren, A., Jabbar, A., & Luo, M. (2021). Examining the role of consumer satisfaction within mobile eco-systems: Evidence from mobile banking services. Computers in Human Behavior, 114, 106584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, P., Garg, A., Sharma, A., & Rana, N. P. (2022). I won’t touch money because it is dirty: Examining customer’s loyalty toward M-payment. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 40(5), 992–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X., & Jiang, X. (2023). Understanding consumer impulse buying in livestreaming commerce: The product involvement perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1104349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GSMA. (2024). The state of the industry report on mobile money 2024. Global system for mobile communications (pp. 1–96). Available online: https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/260224-The-Mobile-Economy-2024.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Gupta, A., Yousaf, A., & Mishra, A. (2020). How pre-adoption expectancies shape post-adoption continuance intentions: An extended expectation-confirmation model. International Journal of Information Management, 52, 102094. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0268401219305857 (accessed on 9 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S., & Dhingra, S. (2022). Past, Present and future of mobile financial services: A critique, review and future agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 46(6), 2104–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M. S., Islam, M. A., Sobhani, F. A., Nasir, H., Mahmud, I., & Zahra, F. T. (2022). Drivers influencing the adoption intention towards mobile fintech services: A study on the emerging bangladesh market. Information, 13(7), 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazra, U., & Priyo, A. K. K. (2021). Mobile financial services in Bangladesh: Understanding the affordances. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Counties, 87(3), e12166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhsan, R. B., Fernando, Y., Mariani, V., Gui, A., Fakhrorazi, A., & Wahyuni-TD, I. S. (2023, August 24–25). What makes customers satisfied and continuence using m-fintech payment? The multidimensional investigation of perceived security. International Conference on Information Management and Technology (ICIMTech) (pp. 615–620), Malang, Indonesia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, N., & Shahria, G. (2022). Factors effecting customer satisfaction of mobile banking in Bangladesh: A study on young users’ perspective. South Asian Journal of Marketing, 3(1), 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y. S., & Lee, H. (2010). Understanding the role of an IT artifact in online service continuance: An extended perspective of user satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(3), 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. R., & Chaipoopirutana, S. (2020). Factors influencing users’ behavioral intention to reuse mobile financial services in bangladesh. Journal of Management & Marketing Review (JMMR), 5(3), 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-W., Chan, H. C., & Gupta, S. (2007). Value-based adoption of mobile internet: An empirical investigation. Decision Support Systems, 43(1), 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. The Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Naruetharadhol, P., Ketkaew, C., Hongkanchanapong, N., Thaniswannasri, P., Uengkusolmongkol, T., Prasomthong, S., & Gebsombut, N. (2021). Factors affecting sustainable intention to use mobile banking services. Sage Open, 11(3), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P. (2001). Consumer intentions to adopt electronic commerce-incorporating trust and risk in the technology acceptance model. Digit 2001 Proceedings, 2. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=digit2001 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Pesha, A. V., & Shramko, N. V. (2020, November 5–6). The importance of developing communicative competencies of future specialists in the digital age. 2nd International Scientific and Practical Conference “Modern Management Trends and the Digital Economy: From Regional Development to Global Economic Growth” (MTDE 2020) (pp. 886–892), Yekaterinburg, Russia. Available online: https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/mtde-20/125939674 (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabaa’i, A. A., & ALMaati, S. A. (2021). Exploring the determinants of users’ continuance intention to use mobile banking services in kuwait: Extending the expectation-confirmation model. Asia Pacific Journal of Information Systems, 31(2), 141–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. A., Akter, S., & Rifat, A. (2020). The impact of government support on the adoption of mobile financial services: Evidence from rural Bangladesh. Journal of Financial Technology and Services, 5(2), 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M. M. (2021). Users’ experiences of mobile financial services in rural areas of bangladesh. Shirkah: Journal of Economics and Business, 6(2), 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandra, D. (2016). Factors influencing mobile banking adoption in Kurunegala district, Pakistan. Journal of Information Technology, 1(1), 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rivière, A., & Mencarelli, R. (2012). Towards a theoretical clarification of perceived value in marketing. Recherche et Applications En Marketing (English Edition), 27(3), 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, M. J. (2015). Financial inclusion in Latin America and the Caribbean: Access, usage and quality (Vol. 10). CEMLA. Available online: https://www.findevgateway.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/financial_inclusion_in_latin_america_and_the_caribbean_access_usage_and_quality.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- Rokhimah, R., & Suhermin, S. (2024, July 18–20). Factors influencing continuation intention of mobile Banking usage: Extending the expectancy confirmation model (ECM) and artificial intelligence (AI) with security as moderation. International Conference of Business and Social Sciences (pp. 162–178), Fukuoka, Japan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouf, M. A., Begum, H., & Babu, M. A. (2024). Customer trust and satisfaction: Insights from mobile banking sector in Bangladesh. International Journal of Science and Business, 34(1), 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, R. K., & Ali, M. B. (2024). Does enduring brand loyalty in mobile financial service platforms require strong commitment? A stimulus-organism-response (SOR) perspective. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 29(4), 1623–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saima, F. N., Rahman, M. H. A., & Ghosh, R. (2024). MFS usage intention during COVID-19 and beyond: An integration of health belief and expectation confirmation model. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 40(2), 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A. A., & Karjaluoto, H. (2015). Mobile banking adoption: A literature review. Telematics and Informatics, 32(1), 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A., Mishra, A., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2023). Expectation confirmation theory: A review. In S. Papagiannidis (Ed.), TheoryHub book. Theory Hub. Available online: https://open.ncl.ac.uk/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Sriwidadi, T., & Prabowo, H. (2023). The effect of service quality on customer loyalty through perceived value and customer satisfaction of jakarta mobile banking application. Mix Jurnal Ilmiah Manajemen, 13(3), 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, T. (2023). The mobile financial services: Fast growing financial sector in Bangladesh [Ph.D. Thesis, Brac University]. Available online: https://dspace.bracu.ac.bd/xmlui/handle/10361/18719 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Tse, D. K., & Wilton, P. C. (1988). Models of consumer satisfaction formation: An extension. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(2), 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M. K., & Nasrin, S. (2023). The mediating effect of customer satisfaction on fintech literacy and sustainable intention of using mobile financial services. Open Journal of Business and Management, 11(05), 2488–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M., Odekerken-Schröder, G., & Van Oppen, C. (2009). Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Quarterly, 177–195. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20650284 (accessed on 7 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Williams, B., Onsman, A., & Brown, T. (2010). Exploratory factor analysis: A five-step guide for novices. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winata, H., Thoyib, A., Rohman, F., & Yuniarinto, A. (2024). The effect of perceived risk and customer experience on loyalty intention for mobile banking: The moderating role of customer satisfaction. International Journal of Religion, 5(10), 3405–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J., Ye, L., Huang, W., & Ye, M. (2021). Understanding fintech platform adoption: Impacts of perceived value and perceived risk. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16(5), 1893–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C., Siddik, A. B., Akter, N., & Dong, Q. (2021). Factors influencing the adoption intention of using mobile financial service during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of FinTech. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(22), 61271–61289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Q., Li, H., Wang, Z., & Law, R. (2014). The influence of hotel price on perceived service quality and value in e-tourism: An empirical investigation based on online traveler reviews. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 38(1), 23–39. [Google Scholar]

| Constructs | Items | Loadings | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Value (PV) | PV1: The usefulness of MFS platform is much helping me compared to the effort needed. | 0.75 | ||

| PV2: In terms of time consumption, using MFS is more beneficial. | 0.74 | |||

| PV3: Using MFS delivers value for me compared to fees or costs that need to be paid. | 0.74 | |||

| PV4: Because of many proportional benefits, employing MFS is financially viable. | 0.77 | |||

| PV5: Overall, the MFS platform offers decent value. | 0.81 | 0.8443 | 0.58 | |

| Perceived Risk (PR) | PR1: There is little chance of fraud while using MFS. | 0.77 | ||

| PR2: Hacking (OTP, Password) of an MFS account is not very likely. | 0.76 | |||

| PR3: There is little chance of bad transactions because of network issues. | 0.73 | |||

| PR4: Using MFS transactions is not riskier than using regular transaction techniques (Cash, card). | 0.79 | |||

| PR5: MFS safeguards my privacy and transactions. | 0.76 | 0.8427 | 0.60 | |

| Perceived Cost (PC) | PC1: The MFS cash-out charge is minimal. | 0.74 | ||

| PC2: The MFS balance transfer charge is minimal. | 0.74 | |||

| PC3: Merchant payment and pay bill charges are minimal while using MFS. | 0.75 | |||

| PC4: There is no hidden charge while using MFS. | 0.73 | |||

| PC5: Compared to banking transaction costs, MFS is less expensive. | 0.77 | 0.8398 | 0.56 | |

| Government Support (GS) | GS1: The government has approved the usage of MFS in Bangladesh. | 0.73 | ||

| GS2: The government is actively putting in place the infrastructure needed to make MFS use easier. | 0.80 | |||

| GS3: The government has passed laws and regulations that benefit MFS. | 0.76 | |||

| GS4: The government must provide financial and legal support for MFS to be used effectively. | 0.72 | 0.7960 | 0.57 | |

| Perceived Trust (PT) | PT1: The MFS system is reliable. | 0.75 | ||

| PT2: The MFS system is safe. | 0.79 | |||

| PT3: Through the MFS channel, service is guaranteed. | 0.80 | |||

| PT4: The MFS channel’s technological and legal support protects me from issues. | 0.75 | |||

| PT5: I do believe MFS is trustworthy. | 0.77 | 0.8551 | 0.60 | |

| Satisfaction (SAT) | SAT1: I am pleased that I am utilizing the MFS. | 0.80 | ||

| SAT2: My MFS usage experience was satisfactory. | 0.79 | |||

| SAT3: MFS has allowed me to make personal financial decisions with only a few clicks. | 0.84 | |||

| SAT4: I made the proper choice to use MFS. | 0.81 | |||

| SAT5: I was satisfied with MFS overall. | 0.85 | 0.8857 | 0.67 | |

| Continuance of Use (COU) | COU1: Using MFS has become a daily requirement for many people. | 0.84 | ||

| COU2: I got used to using MFS. | 0.88 | |||

| COU3: I am unable to stop using MFS. | 0.85 | |||

| COU4: I plan to keep using MFS since those around me are growing dependent on it. | 0.85 | 0.8838 | 0.73 |

| PV | PR | PC | GS | PT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV | 0.762 | 0.015 | 0.034 | 0.067 | −0.021 |

| PR | 0.015 | 0.765 | −0.034 | −0.034 | −0.010 |

| PC | 0.034 | −0.034 | 0.746 | 0.006 | 0.039 |

| GS | 0.067 | −0.034 | 0.006 | 0.755 | 0.055 |

| PT | −0.021 | −0.010 | 0.039 | 0.055 | 0.774 |

| Construct | √AVE | Max Correlation with Others | Passes FL? |

|---|---|---|---|

| PV | 0.762 | 0.067 (with GS) | Yes |

| PR | 0.765 | 0.034 (with PV) | Yes |

| PC | 0.746 | 0.039 (with PT) | Yes |

| GS | 0.755 | 0.067 (with PV) | Yes |

| PT | 0.774 | 0.055 (with GS) | Yes |

| Variable Group | Items | MSA Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PR (Perceived Risk) | PR1, PR2, PR3, PR4, PR5 | 0.77–0.86 | All items have an acceptable sampling adequacy; PR4 has the lowest value but is still acceptable. |

| PC (Perceived Cost) | PC1, PC2, PC3, PC4, PC5 | 0.80–0.83 | All items show good sampling adequacy, indicating suitability for analysis. |

| GS (Government Support) | GS1, GS2, GS3, GS4 | 0.75–0.83 | Acceptable values, though GS1 and GS3 are on the lower end. |

| PT (Perceived Trust) | PT1, PT2, PT3, PT4, PT5 | 0.86–0.89 | High sampling adequacy, suitable for factor analysis. |

| PV (Perceived Value) | PV1, PV2, PV3, PV4, PV5 | 0.82–0.85 | Good sampling adequacy across all items. |

| SAT (Satisfaction) | SAT1, SAT2, SAT3, SAT4, SAT5 | 0.90–0.93 | Excellent sampling adequacy, indicating a very strong factor structure. |

| COU (Continuance of Use) | COU1, COU2, COU3, COU4 | 0.88–0.93 | Excellent sampling adequacy across all items. |

| Relations | Path Coefficient | t-Statistics | p-Value | Decision | Q2 | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAT | ~ | PV | 0.210128 | 3.95632 ** | <0.01 | Supported | 0.8913348 | 0.3738413 |

| SAT | ~ | PR | −0.153807 | −2.9862 ** | <0.01 | Supported | ||

| SAT | ~ | PC | −0.100052 | −1.85556 * | 0.06 | Supported | ||

| SAT | ~ | GS | 0.201831 | 3.6769 ** | <0.01 | Supported | ||

| SAT | ~ | PT | 0.496830 | 10.9392 ** | <0.01 | Supported | ||

| COU | ~ | SAT | 0.699662 | 20.784 ** | <0.01 | Supported | 0.9038131 | 0.4895269 |

| Directions | Estimate | SE | Confidence Interval | Standardized Estimate | p Value | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||||

| SAT ~ PV | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.34 | 0.21 | <0.01 | Medium Effect |

| SAT ~ PR | −0.16 | 0.05 | −0.26 | −0.05 | −0.15 | <0.01 | Small Effect |

| SAT ~ PC | −0.11 | 0.06 | −0.22 | 0.01 | −0.10 | 0.06 | Small Effect |

| SAT ~ GS | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.34 | 0.20 | <0.01 | Medium Effect |

| SAT ~ PT | 0.53 | 0.06 | 0.42 | 0.64 | 0.50 | <0.01 | Large Effect |

| COU ~ SAT | 0.74 | 0.05 | 0.65 | 0.83 | 0.70 | <0.01 | Large Effect |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rizvee, M.B.; Siddik, M.N.A.; Kabiraj, S. Exploring Antecedents of Rural Users’ Continuance of Use Intention Toward Mobile Financial Services in Bangladesh: Deployment of Expectation Confirmation Model. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050236

Rizvee MB, Siddik MNA, Kabiraj S. Exploring Antecedents of Rural Users’ Continuance of Use Intention Toward Mobile Financial Services in Bangladesh: Deployment of Expectation Confirmation Model. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(5):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050236

Chicago/Turabian StyleRizvee, Md. Benzeer, Md. Nur Alam Siddik, and Sajal Kabiraj. 2025. "Exploring Antecedents of Rural Users’ Continuance of Use Intention Toward Mobile Financial Services in Bangladesh: Deployment of Expectation Confirmation Model" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 5: 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050236

APA StyleRizvee, M. B., Siddik, M. N. A., & Kabiraj, S. (2025). Exploring Antecedents of Rural Users’ Continuance of Use Intention Toward Mobile Financial Services in Bangladesh: Deployment of Expectation Confirmation Model. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(5), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050236