An Empirical Evaluation of the Technology Acceptance Model for Peer-to-Peer Insurance Adoption: Does Income Really Matter?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Traditional Insurance Model

2.2. Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Insurance Model

2.3. Factors That Influence the Adoption of Peer-to-Peer Insurance

2.3.1. Perceived Usefulness

2.3.2. Perceived Ease of Use

2.3.3. Perceived Risk

2.3.4. Subjective Norms

2.3.5. Perceived Trust

2.4. Other User-Related Factors

2.5. Purpose and Hypotheses

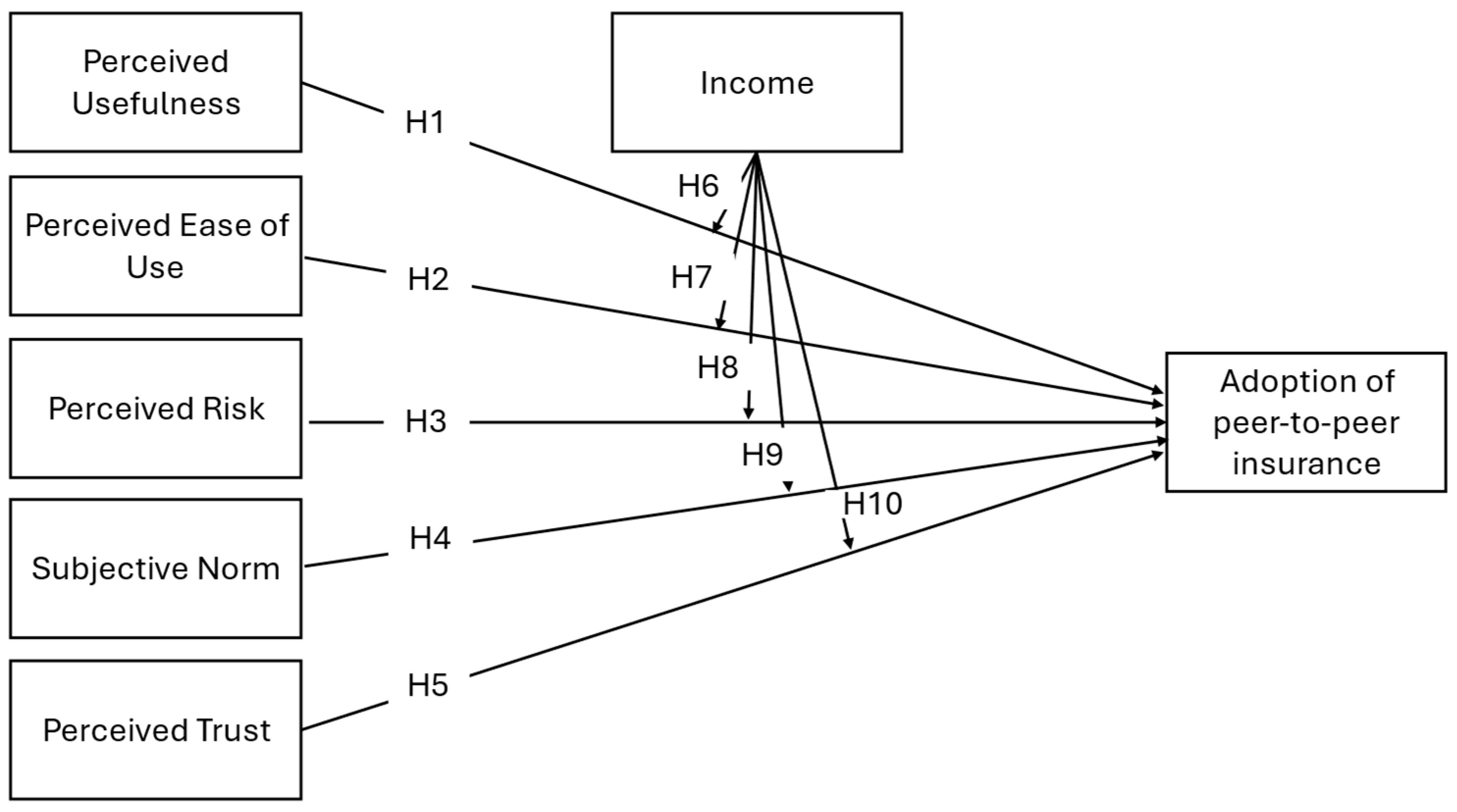

2.6. Conceptual Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sampling

3.2. Profile of Respondents

3.3. Measures

3.4. Analyses

4. Results and Interpretations

4.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

4.2. Discriminant Validity

4.3. Assessment of the Structural Model

4.4. SEM Results (Direct and Moderation Effects)

5. Discussion

5.1. Perceived Usefulness and Intention to Adopt Peer-to-Peer Insurance

5.2. Perceived Ease of Use and Intention to Adopt Peer-to-Peer Insurance

5.3. Perceived Risk and Intention to Adopt Peer-to-Peer Insurance

5.4. Subjective Norms and Intention to Adopt Peer-to-Peer Insurance

5.5. Perceived Trust and Intention to Adopt Peer-to-Peer Insurance

5.6. The Moderating Role of Income on the Nexus Between Perceived Usefulness and the Intention to Adopt P2P Insurance

5.7. The Moderating Role of Income on the Nexus Between Perceived Ease of Use and the Intention to Adopt P2P Insurance

5.8. The Moderating Role of Income on the Nexus Between Perceived Risk and the Intention to Adopt P2P Insurance

5.9. The Moderating Role of Income on the Nexus Between Subjective Norms and the Intention to Adopt P2P Insurance

5.10. The Moderating Role of Income on the Nexus Between Perceived Trust and the Intention to Adopt P2P Insurance

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Due to compliance with the regulatory policy of British motor vehicle insurance, Guevara announced the temporary suspension of operations in November 2017 “www.heyguevara.com (accessed on 17 November 2024).” |

References

- Abdikerimova, S., & Feng, R. (2022). Peer-to-peer multi-risk insurance and mutual aid. European Journal of Operational Research, 299(2), 735–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D. A., Nelson, R. R., & Todd, P. A. (1992). Perceived usefulness, ease of use, and usage of information technology: A replication. MIS Quarterly, 16(2), 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyei, J., Sun, S., Abrokwah, E., Penney, E. K., & Ofori-Boafo, R. (2020). Influence of trust on customer engagement: Empirical evidence from the insurance industry in Ghana. Sage Open, 10(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S., Saxena, C., Islam, S., & Karim, R. (2024). Impact of insur-tech on the premium performance of insurance business. SN Computer Science, 5(1), 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organisational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(4), 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldammagh, Z., Abdeljawad, R., & Obaid, T. (2021). Predicting mobile banking adoption: An integration of TAM and TPB with trust and perceived risk. Financial Internet Quarterly, 17(3), 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gahtani, S. S. (2011). Modeling the electronic transactions acceptance using an extended technology acceptance model. Applied Computing and Informatics, 9(1), 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kurdi, B., Alshurideh, M., Nuseir, M., Aburayya, A., & Salloum, S. A. (2021, March 22–24). The effects of subjective norm on the intention to use social media networks: An exploratory study using PLS-SEM and machine learning approach. International Conference on Advanced Machine Learning Technologies and Applications, Cairo, Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- Alrawad, M., Lutfi, A., Almaiah, M. A., & Elshaer, I. A. (2023). Examining the influence of trust and perceived risk on customers’ intention to use NFC mobile payment system. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(2), 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, R., Beck, R., & Smits, M. T. (2018). FinTech and the transformation of the financial industry. Electronic Markets, 28(2), 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, M., & Cusick, K. (2008). General insurance 2020: Insurance for the individual. Institute of Actuaries of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednarczyk, T. H., & Pasierbowicz, T. (2018). Peer-to-peer insurance: Innovation, revolution, or return to the roots? Przedsiębiorczość i Zarządzanie, 19(3), 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Blankertz, D. F. (1969). Risk-taking and information handling in consumer behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 6(1), 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, A., & Schreiber, F. (2017). The current InsurTech landscape: Business models and disruptive potential (No. 62). I. VW HSG Schriftenreihe. [Google Scholar]

- Carlin, B. I. (2009). Strategic price complexity in retail financial markets. Journal of Financial Economics, 91(3), 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlin, B. I., Longstaff, F. A., & Matoba, K. (2014). Disagreement and asset prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 114(2), 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catacutan, Z. M., & Mabesa, J. J. O. (2024). The mediating roles of trust on intentions toward mobile wallet adoption in social health insurance: A deep learning–based SEM-ANN analysis. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, J., Jiang, B. C., Mufidah, I., Persada, S. F., & Noer, B. A. (2018). The investigation of consumers’ behavior intention in using green skincare products: A pro-environmental behavior model approach. Sustainability, 10(11), 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, I. H. (2016). FinTech and disruptive business models in financial products, intermediation, and markets: Policy implications for financial regulators. Journal of Technology Law & Policy, 21, 55–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, D. (2002). Expanding individual health insurance coverage: Are high-risk pools the answer? Health Affairs, 21(Suppl. S1), W349–W352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, G. P., & Marano, P. (2020). The broker model for peer-to-peer insurance: An analysis of its value. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice, 45(3), 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosma, S., & Rimo, G. (2024). Redefining Insurance through Technology: Achievements and perspectives in Insurtech. Research in International Business and Finance, 70, 102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S., & Saji, K. B. (2008). The role of consumer self-efficacy and website social-presence in customers’ adoption of B2C online shopping: An empirical study in the Indian context. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 20(2), 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gregorio, F., & Sung, Y. (2010). Understanding attitudes toward and behaviors in response to product placement. Journal of Advertising, 39(1), 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denuit, M., Dhaene, J., & Robert, C. Y. (2022). Risk-sharing rules and their properties, with applications to peer-to-peer insurance. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 89(3), 615–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, C., Guillén, M., & Nielsen, J. P. (2014). Bringing cost transparency to the life annuity market. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 56, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörfling, D. F., & Godspower-Akpomiemie, E. (2024). Investigating factors that affect the willingness to adopt peer-to-peer short-term insurance in South Africa. Digital Transformation and Society, 3(2), 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIOPA. (2019). Report on best practices on licencing requirements, peer-to-peer insurance and the principle of proportionality in an InsurTech context. Available online: https://register.eiopa.europa.eu/Publications/EIOPA%20Best%20practices%20on%20licencing%20March%202019.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Emerson, R. W. (2021). Convenience sampling revisited: Embracing its limitations through thoughtful study design. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 115(1), 76–77. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, R., Liu, M., & Zhang, N. (2024). A unified theory of decentralised insurance. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 119, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Beliefs, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebert-Persson, S., Gidhagen, M., Sallis, J. E., & Lundberg, H. (2019). Online insurance claims: When more than trust matters. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(2), 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003). Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Quarterly, 27(1), 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomber, P., Koch, J.-A., & Siering, M. (2017). Digital finance and FinTech: Current research and future research directions. Journal of Business Economics, 87, 537–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhue, D. L., & Thompson, R. L. (1995). Task-technology fit and individual performance. MIS Quarterly, 19, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, I. S. (2024). Insurtech: Disrupting the Insurance Industry. In The Emerald Handbook of Fintech (pp. 343–362). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Guiso, L. (2021). Trust and insurance. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance–Issues and Practice, 46(3), 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Gabriel, M. L., & Patel, V. K. (2014). AMOS covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. REMark: Revista Brasileira de Marketing, 13(2), 44. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamideh, O. S. A., Yousif, A., Alhmeidiyeen, M. S., & Alnsor, N. S. (2018). E-loyalty in marketing: Implications for e-customer focus. International Journal of Business Economics and Management Research, 9(2), 2229–4848. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson, A. R., Massey, P. D., & Cronan, T. P. (1993). On the test-retest reliability of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use scales. MIS Quarterly, 17(2), 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, C. P., & Kavuri, A. S. (2024). Insurtech strategies: A comparison of incumbent insurance firms with new entrants. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice, 50, 78–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvey, S. S., & Odei-Mensah, J. (2024). Factors influencing underwriting performance of the life and non-life insurance markets in South Africa: Exploring for complementarities, nonlinearities, and thresholds. Journal of African Business, 26, 164–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvey, S. S., & Odei-Mensah, J. (2025a). Innovative Pathways in Africa: Navigating the Relationship Between Innovation and Insurance Market Development Through Linear and Non-linear Lenses. Journal of the Knowledge Economy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvey, S. S., & Odei-Mensah, J. (2025b). Towards economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: Is there a synergy between insurance market development and ICT diffusion? Information Technology for Development, 31(1), 178–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inder, S. (2022). Crowdsourcing, insurance and analytics: The trio of insurance future. In Big data: A game changer for insurance industry (pp. 101–115). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishengoma, F. (2024). Revisiting the TAM: Adapting the model to advanced technologies and evolving user behaviours. The Electronic Library, 42(6), 1055–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E., & Kim, Y. (2024). Determinants of user acceptance of digital insurance platform service on InsurTech: An empirical study in South Korea. Asian Journal of Technology Innovation, 33, 45–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiwanuka, A., & Sibindi, A. B. (2024). Digital literacy, Insurtech adoption and Insurance inclusion in Uganda. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(3), 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S., Toker, A., & Brulez, P. (2011). Extending the technology acceptance model with perceived community characteristics. Information Research, 16(2), 16–12. [Google Scholar]

- Leshem, S., & Trafford, V. (2007). Overlooking the conceptual framework. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 44(1), 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levantesi, S., & Piscopo, G. (2022). Mutual peer-to-peer insurance: The allocation of risk. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, 10(1), 100154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W. M., & Weissmann, M. A. (2023). Toward a theory of behavioral control. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 31, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. S. C., & Hsieh, P. L. (2006). The role of technology readiness in customers’ perception and adoption of self-service technologies. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 17(5), 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Tang, L., Kim, E., & Wang, X. (2022). Hierarchal formation of trust on peer-to-peer lodging platforms. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 46(7), 1384–1410. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y. L., & Ren, Y. (2023). InsurTech—Promise, threat or hype? Insights from stock market reaction to InsurTech innovation. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 80, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, T. J., Ellen, P. S., & Ajzen, I. (1992). A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(1), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A. A., Rahman, M. K., Munikrishnan, U. T., & Permarupan, P. Y. (2021). Predicting the intention and purchase of health insurance among Malaysian working adults. Sage Open, 11(4), 21582440211061373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M. M., Ismail, N. A., & Rahman, M. (2020). A conceptual framework for purchase intention of sustainable life insurance: A comprehensive review. International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development, 14(3), 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Husin, M., Ismail, N., & Ab Rahman, A. (2016). The roles of mass media, word of mouth and subjective norm in family takaful purchase intention. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 7(1), 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanović, N., Milosavljević, M., Benković, S., Starčević, D., & Spasenić, Ž. (2020). An acceptance approach for novel technologies in car insurance. Sustainability, 12(24), 10331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moenninghoff, S. C., & Wieandt, A. (2013). The future of peer-to-peer finance. Schmalenbachs Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung, 65, 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Weiss, M. M., & Calantone, R. (1994). Determinants of new product performance: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 11(5), 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naicker, V., & Van Der Merwe, D. B. (2018). Managers’ perception of mobile technology adoption in the Life Insurance industry. Information Technology & People, 31(2), 507–526. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). An overview of psychological measurement. In Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders: A handbook (pp. 97–146). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowska, M., & Ziemiak, M. P. (2020). The concept of P2P insurance: A review of literature and EIOPA report. Insurance Law, 1(102), 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poan, R., Merizka, V. E., & Komalasari, F. (2022). The importance of trust factor in the intentions to purchase Islamic insurance (takaful) in Indonesia. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 13(12), 2630–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S. A., Ahmed, R., Ali, M., & Qureshi, M. A. (2020). Influential factors of Islamic insurance adoption: An extension of theory of planned behavior. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 11(6), 1497–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, M. L., & Carvalho, J. C. (2020). Insurance in today’s sharing economy: New challenges ahead or a return to the origins of insurance? In InsurTech: A legal and regulatory view (pp. 27–47). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichheld, F. F., & Schefter, P. (2000). E-loyalty: Your secret weapon on the web. Harvard Business Review, 78(4), 105–113. Available online: https://www.pearsoned.ca/highered/divisions/text/cyr/readings/Reichheld_SchefterT2P1R1.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Schiopu, I. (2015). Technology adoption, human capital formation and income differences. Journal of Macroeconomics, 45, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segars, A. H., & Grover, V. (1993). Re-examining perceived ease of use and usefulness: A confirmatory factor analysis. MIS Quarterly, 17(4), 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y. Y., & Fang, K. (2004). The use of a decomposed theory of planned behavior to study Internet banking in Taiwan. Internet Research, 14(3), 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidani, Y., Zbib, I., Rawwas, M., & Moussawer, T. (2009). Gender, age, and ethical sensitivity: The case of Lebanese workers. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 24(3), 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, I., & Montes, Ó. (2022). Understanding the InsurTech dynamics in the transformation of the insurance sector. Risk Management and Insurance Review, 25(1), 35–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, A. T., & Toubia, O. (2010). Deriving value from social commerce networks. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(2), 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, G. H. (1994). A replication of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use measurement. Decision Sciences, 25(5–6), 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szajna, B. (1994). Software evaluation and choice: Predictive validation of the technology acceptance instrument. MIS Quarterly, 18(3), 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q., Tong, Z., & Xun, L. (2022). Insurance risk analysis of financial networks vulnerable to a shock. European Journal of Operational Research, 301(2), 756–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, A. C., Tan, G. W. H., Cheah, C. M., Ooi, K. B., & Yew, K. T. (2012). Can the demographic and subjective norms influence the adoption of mobile banking? International Journal of Mobile Communications, 10(6), 578–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, M., & Ilankadhir, M. (2024). Determinants of Digital Insurance Adoption among Micro-Entrepreneurs in Uganda. Financial Engineering, 2, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uche, D. B., Osuagwu, O. B., Nwosu, S. N., & Otika, U. S. (2021). Integrating trust into technology acceptance model (TAM): The conceptual framework for e-payment platform acceptance. British Journal of Management and Marketing Studies, 4(4), 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varpio, L., Paradis, E., Uijtdehaage, S., & Young, M. (2020). The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. Academic Medicine, 95(7), 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., & Bala, H. (2008). Technology acceptance model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decision Sciences, 39(2), 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., & Zhang, X. (2010). Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: US vs. China. Journal of Global Information Technology Management, 13(1), 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. (2023). Discussion on the value-added space of digital transformation of insurance industry. Academic Journal of Business & Management, 5(6), 51–56. [Google Scholar]

| Constructs | Items | Loadings | Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Risk (Dash & Saji, 2008) | 0.853 | 0.868 | 0.696 | ||

| PR1 | 0.831 | ||||

| PR2 | 0.898 | ||||

| PR3 | 0.746 | ||||

| PR4 | 0.854 | ||||

| Perceived Usefulness (Davis, 1989) | 0.942 | 0.951 | 0.852 | ||

| PU1 | 0.866 | ||||

| PU2 | 0.953 | ||||

| PU3 | 0.939 | ||||

| PU4 | 0.932 | ||||

| Perceived Ease of Use (Davis, 1989) | 0.937 | 0.943 | 0.841 | ||

| PEOU1 | 0.914 | ||||

| PEOU2 | 0.867 | ||||

| PEOU3 | 0.959 | ||||

| PEOU4 | 0.926 | ||||

| Subjective Norms (Venkatesh & Davis, 2000; Shih & Fang, 2004) | 0.867 | 0.917 | 0.880 | ||

| SN1 | 0.920 | ||||

| SN2 | 0.956 | ||||

| Perceived Trust (Dash & Saji, 2008) | 0.812 | 0.934 | 0.789 | ||

| TRU1 | 0.923 | ||||

| TRU2 | 0.910 | ||||

| TRU3 | 0.921 | ||||

| TRU4 | 0.901 | ||||

| TRU5 | 0.899 | ||||

| PU | PEOU | SN | PR | TRU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU | 0.93 | ||||

| PEOU | 0.8 *** | 0.92 | |||

| SN | 0.37 *** | 0.4 *** | 0.94 | ||

| PR | 0.57 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.85 | |

| TRU | 0.73 *** | 0.75 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.77 *** | 0.89 |

| H | Path | β Estimate | t-Value | p-Value | Interpretation | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Relationship | ||||||

| H1 | PU → BI | 0.413 | 3.153 | 0.002 | Significant | Accepted |

| H2 | PEOU → BI | 0.167 | 4.913 | 0.000 | Significant | Accepted |

| H3 | PR → BI | 0.230 | 1.756 | 0.079 | Not Significant | rejected |

| H4 | SN → BI | 0.220 | 2.716 | 0.034 | Significant | Accepted |

| H5 | TRU → BI | 0.066 | 0.455 | 0.618 | Not Significant | Rejected |

| Moderation Effects | ||||||

| H6 | PU*Income → BI | 0.272 | 3.106 | 0.002 | Significant | Accepted |

| H7 | PEOU*Income → BI | 0.287 | 3.102 | 0.002 | Significant | Accepted |

| H8 | PR*Income → BI | 0.356 | 1.020 | 0.308 | Not Significant | Rejected |

| H9 | SN*Income → BI | 0.848 | 2.382 | 0.017 | Significant | Accepted |

| H10 | TRU*Income → BI | 0.310 | 0.851 | 0.394 | Not Significant | Rejected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Horvey, S.S.; Godspower-Akpomiemie, E.; Asare Boateng, R. An Empirical Evaluation of the Technology Acceptance Model for Peer-to-Peer Insurance Adoption: Does Income Really Matter? J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040209

Horvey SS, Godspower-Akpomiemie E, Asare Boateng R. An Empirical Evaluation of the Technology Acceptance Model for Peer-to-Peer Insurance Adoption: Does Income Really Matter? Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(4):209. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040209

Chicago/Turabian StyleHorvey, Sylvester Senyo, Euphemia Godspower-Akpomiemie, and Richard Asare Boateng. 2025. "An Empirical Evaluation of the Technology Acceptance Model for Peer-to-Peer Insurance Adoption: Does Income Really Matter?" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 4: 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040209

APA StyleHorvey, S. S., Godspower-Akpomiemie, E., & Asare Boateng, R. (2025). An Empirical Evaluation of the Technology Acceptance Model for Peer-to-Peer Insurance Adoption: Does Income Really Matter? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(4), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18040209