Abstract

Sustainable property development in developing economies requires a careful balance between attracting foreign capital and maintaining housing affordability for local residents. While foreign direct investment (FDI) serves as a crucial engine for economic growth by enhancing productive capacity and international competitiveness, its effects on local housing markets remain inadequately understood in policy frameworks. This study examines how economic development strategies can be designed to harness FDI benefits while preventing residential market distortions in rapidly industrializing regions. Using Malaysia’s Kulim Hi-Tech Park and Batu Kawan Industrial Park as empirical cases, we analyze the relationship between foreign capital inflows and residential property prices from 2000 to 2022 through time-series regression analysis supplemented by stakeholder consultations. Our findings reveal that FDI significantly influences housing price dynamics in industrial zones, with both positive economic spillovers and challenges for housing affordability. The results demonstrate that targeted policy interventions—including affordable housing mandates, developer incentives, and strategic land use planning—can effectively moderate price appreciation while maintaining investment attractiveness. This research contributes to evidence-based policymaking by identifying integrated mechanisms that promote sustainable and inclusive growth in emerging economies seeking to balance industrial advancement with equitable housing access. The Malaysian experience offers valuable practical insights for policymakers in developing nations navigating the complex relationship between international investment, housing markets, and social welfare.

1. Introduction

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has emerged as a critical driver of economic development in emerging economies. While its contributions to economic growth, technological advancement, and job creation are well documented, the spillover effects of foreign capital on residential property markets remain underexplored, particularly in rapidly industrializing regions. This relationship between investment flows and housing affordability presents a significant policy challenge for developing nations seeking to balance economic advancement with sustainable urban development.

The conventional wisdom that FDI stimulates economic growth is supported by substantial empirical evidence (Durham, 2004; Greenaway et al., 2004; Z. Liu, 2008; Sinani & Meyer, 2004). Foreign capital inflows, when effectively integrated into a host country’s development strategy, enhance productive capacity and international competitiveness (UNCTAD, 2015, 2016). However, as industrial development accelerates and urban populations expand in response to economic opportunities, housing markets often experience significant price pressures that can undermine affordability and social welfare.

Historically, FDI has concentrated in manufacturing sectors, but recent decades have witnessed a shift toward service sectors, including significant investments in real estate development (Ahmad & Malawat, 2010; Hui & Chan, 2014; Masron & Md Nor, 2016). This evolving pattern of investment carries important implications for housing markets in developing economies. Residential property not only provides shelter but also represents a primary source of household wealth and investment. The real estate sector’s contribution to employment and economic activity is substantial, with construction activities generating significant labor demand. Consequently, fluctuations in housing construction can significantly impact unemployment rates, affordability levels, and overall economic stability (Masron & Md Nor, 2016; Harris & Arku, 2006).

While FDI can stimulate property development in host countries, studies by Richards (2005), Mihaljek (2005), and Prasad et al. (2007) suggest that capital inflows may also drive housing price appreciation, potentially compromising affordability. However, the recommendation to restrict foreign investment flows oversimplifies a complex market dynamic. Property prices and housing affordability are influenced by multiple factors beyond foreign investment, including interest rates, land availability, development costs, state policies, planning regulations, taxation structures, and labor costs (Capozza et al., 2002; Fan et al., 2006; Zietz et al., 2008).

The Malaysian context provides a particularly instructive case for examining these dynamics. According to the Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021) reports from 2015–2021, FDI in Malaysia has increased dramatically in recent years, rising from RM36.1 billion in 2015 to RM85.38 billion in 2019. This surge reflects Malaysia’s strategic positioning within global supply chains and the relocation of businesses amid international trade tensions. The country experienced a significant milestone in 2021 when foreign investment net inflows exceeded USD$20 billion. The Asian region has consistently been the largest contributor to Malaysia’s FDI flows over the past decade, followed by Europe and America. Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan represent the major Asian investors, while the Netherlands and Switzerland lead European investment. Kulim Hi-Tech Park (KHTP) and Batu Kawan Industrial Park (BKIP) have emerged as premier destinations for foreign investment, particularly in semiconductors and electronics manufacturing (MIDA, 2022).

Despite this investment-driven growth, Malaysia’s real estate market faces persistent challenges, including an oversupply of residential units, property overhang, declining housing affordability, and concerns about market bubbles (Ab Majid et al., 2017; Ling et al., 2017; Yin et al., 2019). The National Property Information Centre (NAPIC) reported that unsold completed residential units increased by 281 percent between 2014 and 2018, while the value of residential overhang surged by 635 percent. This dramatic rise reflects rapidly increasing property prices and softening demand for higher-priced properties. As of 2022, residential unsold units still exceeded 25,000, presenting significant concerns for investors, developers, and prospective homebuyers (NAPIC, 2022).

Previous research has extensively examined housing affordability in Malaysia (Olanrewaju & Tan, 2018; Soon & Tan, 2020; Yap & Ng, 2018) and the challenges facing the housing sector (Khazanah Research Institute, 2019; Ong, 2013; Osmadi et al., 2015). However, studies specifically addressing the impact of FDI on Malaysia’s residential property markets remain scarce (Masron & Md Nor, 2016), and virtually none have focused on the distinctive dynamics of housing markets adjacent to major industrial zones. This research gap is particularly significant for policy development in Malaysia and other emerging economies where industrial parks serve as magnets for foreign investment. Understanding how housing markets respond to these capital inflows is essential for designing policies that maximize economic benefits while preserving housing affordability and social welfare. Therefore, this study investigates the relationship between FDI and residential property markets in the vicinity of Kulim Hi-Tech Park and Batu Kawan Industrial Park, examining both price dynamics and market stability from 2000 to 2022.

By analyzing how industrial development and foreign investment influence residential property markets, this research aims to inform policy frameworks that can effectively balance economic growth objectives with housing affordability concerns. The findings contribute to the broader understanding of sustainable development in emerging economies facing the dual challenges of attracting international investment and ensuring equitable access to housing for local populations.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the theoretical background on demand–supply theory. Section 3 highlights the previous studies’ analyses related to foreign investment impacts on property markets globally, as well as the Malaysian housing context. Section 4 details the methodology, including the empirical model specification, data sources, and analytical approach. Section 5 presents the results and findings, examining trends in property markets near industrial zones and the relationship between housing prices, FDI, and macroeconomic variables. Section 6 outlines the discussions and policy recommendations for sustainable property development in industrial zones. Finally, Section 7 concludes with lessons applicable to other developing economies and suggestions for future research directions.

2. Theoretical Background

Economists, like Adam Smith, understood supply and demand through observable monetary values: the buyer’s maximum willingness to pay (WTP) and the seller’s minimum willingness to accept (WTA), defining supply and demand through reservation prices. This approach contrasts with neoclassical models that emphasize utility functions and continuous economic variables. Notably, economist Alfred Marshall (1890) attempted to reconcile classical views with marginalist ideas, using the ‘pairs of scissors’ metaphor to highlight the dual importance of utility and cost in determining value. Classical demand theory is grounded in a hierarchy of needs ranging from necessities to luxuries, influencing consumer choices and willingness to pay. On the supply side, classical economists considered production costs, including labor, materials, and capital depreciation, as the basis for minimum acceptable prices, ensuring producers’ willingness to supply goods profitably.

The demand for housing is indicated by price, household income, household composition, job choice, and housing consumption. As the price of a particular quality of housing unit increases, households demand less of that quality housing. For that reason, as the housing cost burden of a household increases, the household must either find less costly housing or reduce consumption of other goods. The location of a unit is important when considering commute times and if the household includes children. Capital markets should also be considered when examining the demand for housing. As mortgage rates decrease, households may have a greater incentive to invest in purchasing a home as home ownership becomes more affordable and will, therefore, demand fewer rental units (Arnott, 1987).

The supply of housing responds only partially to cyclical movements in demand because of lags in construction. As a result, rent or home prices move pro-cyclically. According to Arnott (1987), the supply of housing is fixed in the short run, driving up the price of housing as demand increases during times of economic growth. Measuring the change in housing units over time provides an assessment of the supply of housing. Governments require building permits as a method to ensure that proposed construction complies with health and safety codes. Building permits also provide a means of examining the increase in the supply of new units and the rehabilitation of existing housing. Examining vacancy rates provides a third measure of the housing supply. High vacancy rates suggest the demand for housing is low, and thus, fewer housing units will be constructed.

From the macroeconomic perspective, house prices are derived from the disequilibrium of housing demand and supply (DiPasquale & Wheaton, 1992). Fundamental economic principles of supply and demand theory are central to housing market dynamics. House prices are determined by the interaction between the supply of available housing and the demand for it, where the demand-side factors are influenced by population growth, employment, income levels, and interest rates. For example, a significant shift affecting population and labor market opportunities in one location affects housing demand in a wider range of areas, where the buyers are more willing to substitute across residential options to take advantage of lower housing prices in other places, which allows areas with more flexible housing supply to accommodate demand (Baum-Snow & Han, 2024).

A rise in demand, without a corresponding increase in supply, could lead to higher house prices. By way of example, in cities where housing supply is constrained, the increase in labor demand is mainly reflected in higher housing prices (Accetturo et al., 2021). However, higher housing supply elasticity, in turn, has reduced the effect on house prices. Kuang and Liu (2015) pointed out that to curb soaring housing prices, the balance between supply and demand should be maintained, while a few economic factors should be controlled. House prices, in particular, indicate price stickiness. The rationale was that property would not respond to the economic news immediately. For instance, housing demand drops when the economy busts, but price drops on a smaller magnitude when sellers become reluctant to sell at a lower price. The international macroeconomic impact has been highlighted by Sutton (2002) and Terrones and Otrok (2004). They have concluded that house prices strongly correspond to changes in the global economy. On the other hand, the feedback effect from the housing market on economic activity is equally important, as housing can also be treated as an asset.

There are many studies that have been performed on the property market. However, studies that focus on FDI in the property/real estate sector are scarce. First, we review past studies that have been performed worldwide. Then, we focus on studies in Malaysia.

3. Literature Reviews

3.1. International Evidence

Many studies that look at real estate value show that property price movements are influenced by several economic indicators, such as real income growth, interest rate, stock prices, and population growth (Hashim, 2010; Otrok & Terrones, 2004; Xu, 2017; Sutton et al., 2017). For example, real income growth affects a household’s purchasing power and borrowing amount, interest rate affects the cost of borrowing and payback ability, stock prices relate to a household’s wealth and investment options, and population growth is a proxy for the growth rate of a household. Additionally, supply conditions and economic activities are also considered as factors influencing property price movements, where supply condition is associated with availability and choice of housing and economic activities, particularly consumption related to the housing market. Generally, those studies show that economic indicators help to stimulate the local housing market to be more dynamic (Hashim, 2010; Otrok & Terrones, 2004).

Issues pertaining to housing supply in the real estate market have been a major concern among researchers over the years. OECD (2011) and Lee (2016) suggested that a slow response of housing supply to a sudden increase in housing demand, housing policies, and lower purchase transactions can affect the residential property market. Similarly, Capozza et al. (2002) and Jing (2014) found that a crisis of unbalance between demand–supply houses and a limited number of affordable houses in the real estate market could be due to other factors, such as income, land supply, user cost, developer’s profit margin, and the real cost of construction.

Stepanyan et al. (2010) are among the earlier researchers who studied the role of external financing in the property market. They found a significant impact of foreign capital in both dimensions, the short- and long-run, on residential property price. Likewise, Tumbarello and Wang (2010) also studied the effect of private capital inflows on property price changes and highlighted that large capital inflows were associated with an increase in property prices in some countries, such as Denmark, New Zealand, Norway, and Sweden. Conversely, Mihaljek (2005) indicates that foreign capital inflows are found to correlate negatively with property price in Australia.

There are numerous previous studies investigating FREI (foreign real estate investment) in different countries. The studies indicate either the factors affecting foreign direct investment (FDI) in the real estate market or the impact of FDI on the real estate market itself. According to the Dart (2023), the relatively simple taxation system has led to a reduction in UK businesses’ tax bills, making it an appealing destination for investment. The improvement in the UK’s property market, with new-build properties experiencing a significant price increase, has further encouraged real estate investors. The rise in demand coupled with limited new property supply, especially in London, has contributed to the increasing property values (Regency Invest, 2024). The Foreign Real Estate Investment (FREI) in the UK shows statistically significant correlations with gross domestic product (GDP), wages, property prices, land prices, and interest rates, with a positive relationship observed for all explanatory variables except interest rates (Poon, 2017).

Studies by Salem and Baum (2016) highlight the importance of political stability as the most significant driver in attracting real estate investments in the examined Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries. The findings emphasize that political stability is crucial for attracting FDI in the real estate sector, and instability acts as a major obstacle. The study suggests that policymakers in the MENA region need to recognize and address political risks, which are identified as the greatest hindrance to the development of their real estate markets. This consideration becomes particularly relevant in the context of events in the region post-2009, highlighting the importance of incorporating these findings into future policymaking efforts.

Additionally, Joghee et al. (2020) conclude that Dubai is a relatively low-risk destination for investment, supported by a consistent flow of FDI in recent years. Investors from various countries, including Saudi Arabia, Japan, the UK, the USA, and globally, have experienced high dividend-yielding returns in Dubai’s real estate sector. The study notes an exception during the global financial crisis when the real estate market faced challenges. Overall, the findings suggest Dubai’s real estate sector is perceived as favorable for investors, offering attractive returns with a stable investment environment.

The economic literature indicates that FDI, similar to foreign investment in other service sectors, is expected to contribute to a host country’s economic development. This contribution is anticipated through the injection of financial resources; the provision of services in terms of supply, cost, quality, and variety; the introduction of additional competition; the generation of employment opportunities; and the transfer of technology (Arnold et al., 2006), UNCTAD (2004), and Golub (2009). Contrary to the notion that FDI is the leading cause of decreasing affordability in real estate, the study by Anderson et al., 2020 indicates that FDI in real estate often contributes to the rising income of the country. This increased income, in turn, stimulates demand, potentially leading to higher property prices. However, the study reveals no evidence of cointegration and an absence of Granger causality between FDI and the Housing Affordability Index (HAI). Ultimately, the results suggest that FDI is not the cause of decreasing housing affordability in Malaysia. Hui and Chan (2014) identify GDP per capita and the number of foreign real estate enterprises as the most significant factors influencing foreign investment in China’s real estate market. This indicates that China’s economic growth and its increasingly open market play a crucial role in the growing trend of foreign investment in its real estate sector.

Not all previous research shows the positive impact of FDI. For example, Nguyen (2011) addresses the potential risks associated with a surge in FDI in Vietnam’s real estate and construction sectors. While large FDI inflows may suggest an outwardly oriented economy, the paper argues that such investments may not be stable and could pose challenges to sustainable economic growth. The identified risks include instability in the balance of payments and foreign reserves, a widening trade deficit due to increasing intermediate import demand and declining competitiveness of manufacturing exports, and the creation of a real estate bubble that leads to rising bad debts and insolvency in the banking sector.

3.2. Evidence from Malaysia

The real estate market has been viewed as a key point of interest for economists and researchers in Malaysia, where the residential housing market is important and always plays a role in affecting the development of Malaysia’s economy. It is a supply-driven market where property prices are determined by top-to-bottom approaches, such as government, banks, and suppliers (InterNations, 2013). The growth of industrialization and urbanization, especially in urban areas, often faces a serious shortage of land space for development and has caused the property value to appreciate (Y. Liu et al., 2022). In fact, the high level of price has made it unaffordable for low- and middle-income households to purchase a house (Soon & Tan, 2020). Issues on home ownership in towns and cities have also raised concern among Malaysians. Owning a house is considered essential among family members where housing affordability or ‘rumah mampu milik’ is needed by homeowners to secure their life-long investment (Hashim, 2010).

FDI has been a key driver underlying the strong growth performance experienced by the Malaysian economy (MIDA, 2018). Policy reforms, including the introduction of the Investment Incentives Act 1968, the establishment of free trade zones in the early 1970s, and the provision of export incentives alongside the acceleration of open policy in the 1980s, led to a surge of foreign direct investment in the late 1980s. Apart from these policy factors, it is generally believed that sound macroeconomic management, sustained economic growth, and the presence of a well-functioning financial system have made Malaysia an attractive prospect for foreign capital (Ang, 2008). The strategy of developing property policy to allow higher foreign capital inflows, which can stimulate the economy, raised several issues regarding its effectiveness (Masron & Md Nor, 2016).

In Malaysia, many existing studies have been performed on real property issues and problems, but these studies do not focus on the impact of foreign direct investment on Malaysia’s real estate market development. Additionally, these existing studies in Malaysia do not focus specifically on Kulim Hi-Tech Park and Batu Kawan Industrial Park. In addition, we include both industrial parks in this study since they recorded higher foreign direct investment value compared to other industrial parks in Malaysia in 2021. To our knowledge, there are limited studies on the property market (property price and demand) with respect to FDI in Malaysia. Therefore, it is relevant to study how FDI affects property price and demand and the impacts of FDI on the local real estate market in Kulim Hi-Tech Park and Batu Kawan Industrial Park.

4. Methodology

4.1. Empirical Model

This study aims to identify the relationship between foreign direct investment (FDI) and the residential property price (for single-story and double-story terrace residential house schemes) in Kulim Hi-Tech Park and Batu Kawan Industrial Park. The sample in this study consists of two industrial areas in northern Malaysia: Kulim Hi-Tech Park (KHTP) in Kedah and Batu Kawan Industrial Park (BKIP) in Penang. This study uses both industrial areas as the unit of analysis.

This study employs two different measures of property price as dependent variables: the house price and house price index. The house price reflects localized, transaction-specific data, offering a detailed view of the housing market and enabling the analysis of property values and the factors that influence prices at the transaction level. In contrast, the house price index captures broader state-wide trends, including economic conditions and policy impacts, providing insights into variations in housing demand (Bourassa et al., 2006; Ismail & Nayan, 2021; Malpezzi, 1999).

The main focus variables are FDI and property demand; this study used two measures of property demand, which are the number of property sub-sales and property overhang. According to the National Property Information Centre (NAPIC) Malaysia, sub-sales, or secondary market transactions, reflect the actual demand and liquidity in the property market. This measure captures the willingness of buyers to invest in existing properties, providing insight into overall market confidence and buyer sentiment. Meanwhile, property overhang effectively highlights a gap between supply and demand, making it a crucial measure for understanding demand-side issues. Both measurements help assess real-time property market dynamics and trends.

Macroeconomic drivers such as housing policy, gross domestic product (GDP) at the state level, and inflation rates are used as control variables. According to Noman and Khudri (2015) and Tan et al. (2020), the government’s monetary and fiscal policies have a significant impact on the country’s growth; thus, such variables should be regarded as control variables.

Most estimated house price equations are best viewed as inverted demand equations. Following Muellbauer and Murphy (1997) and most other researchers, the demand for housing services is specified in Equation (1).

where PD is the demand for property, y is average income, PP is the price of property, and Z represents other factors that shift the demand curve. This study utilizes two different measurements of property price, namely house price and house price index.

PD = f(y, PP, Z)

Inverting the demand function to obtain an equation for P yield is shown in Equation (2).

PP = g(PD, y, INF)

Other factors include the inflation rate (INF) as a control variable. Since we are interested in looking at the effect of FDI and housing policy on housing price, we include both of them as independent variables.

Thus, the empirical model of property prices uses the following specification in Equation (3):

where FDI is foreign direct investment, DPolicy is housing policy, and INF is inflation rate. GDP is gross domestic product per capita, used as a measure of average income, y.

PP = g(PD, GDP, FDI, DPolicy, INF)

Lagged variables are used in this model to capture the effect that past values of a variable may have on its current or future values. This can happen when the explanatory variable has a causal effect on the response variable, but the effect unfolds gradually and leads to changes in the response over time. In other words, lagged variables capture these delayed effects over time.

Therefore, the final models are as in Equations (4) and (5).

where

PPjt = β0 + β1PDSjt−1 + β2FDIjt−1 + β3DPolicyt + β4GDPjt−1 + β5INFt + εt

PPjt = β0 + β1PDOjt−1 + β2FDIjt−1 + β3DPolicyt + β4GDPjt−1 + β5INFt + εt

- PPjt = Property price in industrial area j at time t

- PDSjt = Sub-sale of property in industrial area j at time t

- PDOjt = Property overhang in industrial area j at time t

- FDIjt = Foreign direct investment in industrial area j at time t

- DPolicyt = Housing policy at time t (DPolicy = 1 if after affordable housing policy

- implementation; DPolicy = 0 if before affordable housing policy implementation)

- GDPjt = Gross domestic product at state level of industrial area j at time t

- INFt = Inflation rate at time t

- εt = error terms

4.2. Selection of Macroeconomics Variables

The housing policy variable is used to capture the effect of affordable housing policy on residential property price. By doing so, the result of the analysis will indicate whether the affordable housing program is able to influence housing price. The performance of the affordable housing policy involves societal demands on affordable houses, leading to political interaction with government (Chowdhury & Panday, 2018). A high-performance democratic institution must be responsive, effective, and sensitive to the demands of its constituents and effective in using limited resources to address those demands (Putnam, 1993).

Real gross domestic product (GDP) is widely recognized as an important economic factor determinant of residential property price movements (Case et al., 2000; De Wit & Van Dijk, 2003; Ong, 2013; Xu, 2017). According to Tsatsaronis and Zhu (2014), real GDP growth has information that contains direct measures of household income and housing price. Englund and Ioannides (1997) and Valadez (2015) indicate that a change in the Property Price Index (HPI) will lead to a change in GDP. For example, Englund and Ioannides (1997) reported that an increase in income is expected to have a positive effect on housing demand and, consequently, on residential property prices. Similarly, Hii et al. (1999) also found that real GDP is significantly related to the residential property price where the property prices increase with real GDP. However, Tsatsaronis and Zhu (2014) and Ganeson and Abdul Muin (2015) found a contradictory result. The authors found that GDP does not have a significant relation with residential property price.

Inflation is also considered a factor that affects property prices in the real estate market (Cho, 2005; Korkmaz, 2019). According to Tsatsaronis and Zhu (2014), the importance of inflation in determining property prices suggests that higher inflation would harm residential property prices for a certain period. The author further described that high inflation could cause a reduction in residential property price growth, especially in the shorter-term period. Nevertheless, inflation and property prices can also have a positive relationship whereby they move in the same direction as residential property prices (Calza et al., 2013). Williams (2015) also found that a reduction in residential property prices is a significant reduction in inflation.

4.3. Data Collection

This study utilizes yearly data from 2010 to 2022 for all variables (house price, house demand, foreign direct investment, housing affordability, gross domestic product, and inflation rate). The secondary data used in the analysis were obtained from the Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA), Department of Statistic Malaysia (DOSM), Municipal Council, National Property Information Centre (NAPIC) Malaysia, the Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) database, and the World Bank database. The residential price data utilized in this investigation were sourced from the Malaysia Property Market Report. The area chosen was similar over the years. In the case of data unavailability for that particular year, the nearby area was chosen, and the data were obtained from the Valuation and Property Services Department (JPPH) and property developers. The data retrieved pertain specifically to single-story terrace and double-story terrace residential house schemes. This selection is based on NAPIC’s statistics, indicating that single-story terrace and double-story terrace properties are the most constructed and sold types compared to other property categories in Malaysia.

In addition to residential property data, this study incorporates other control variables, such as housing policy, gross domestic product, and inflation rates. This comprehensive approach ensures a better understanding, with the macroeconomic variables indirectly revealing the specific impact of FDI on property prices. Time-series data regression is employed to analyze the data in this study, with the sample used being approximately identical, maintaining consistency for robust analysis and interpretation. To obtain insightful information on property price movement near KHTP and BKIP, data regarding developer prices from 2000 to 2022 that were not recorded in the official property stock market report and data regarding the performance of residential property sales were obtained from JPPH Kulim Branch, JPPH Seberang Perai Branch, and property developers.

Based on the discussion above, the sources and measurement units of the variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variables, sources of data, and measurement units.

Additionally, this study also employed expert panel survey analysis with stakeholders and panel experts from relevant organizations, such as the Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA), the Valuation and Property Services Department (JPPH), Penang Development Corporation (PDC), and property developers related to real estate to obtain the insightful impact of FDI on the local real estate market in Kulim Hi-Tech Park and Batu Kawan Industrial Park to support the findings. The list of respondents is as in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of respondents.

5. Results and Findings

5.1. Trends of Kulim Hi-Tech Park (KHTP) and Batu Kawan Industrial Park (BKIP) Property Market

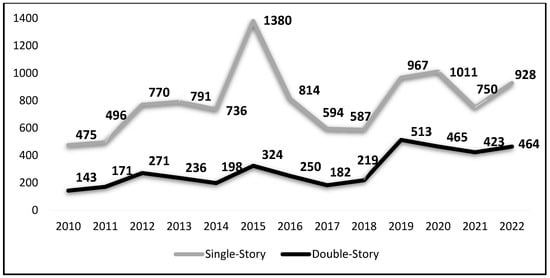

Figure 1 and Figure 2 illustrate the housing demand trends within KHTP and BKIP, revealing distinct preferences. The residential property number of transactions recorded in the NAPIC property market report represents the housing demand for single- and double-story houses. The volume of transactions reflects the level of interest and activity within the real estate market, thus providing a clear gauge of demand. Figure 1 indicates a noteworthy phenomenon: a higher demand for single-story houses in KHTP compared to their double-story counterparts. According to the expert panel of the Director of Valuation and Property Services, Kulim Branch (R2), this trend is significantly influenced by local market preferences and cultural factors. Similarly, the expert panel, including a representative of the Valuation and Property Services Department, Seberang Jaya Branch (R5), stated that in certain areas, the popularity of single-story dwellings is underpinned by cultural preference and their appeal as budget-friendly options for construction and maintenance.

Figure 1.

Trends in housing demand for single-story and double-story properties in KHTP from 2010 to 2022.

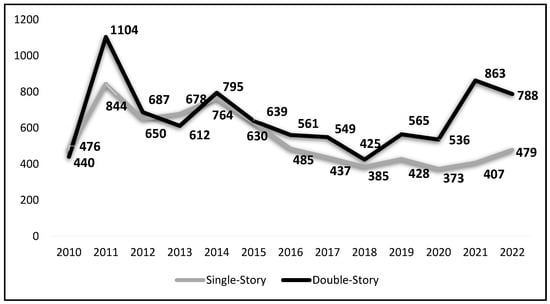

Figure 2.

Trends in housing demand for single-story and double-story properties in BKIP from 2010 to 2022.

However, the landscape shifts in BKIP, as revealed by Figure 2, where the demand for double-story houses surpasses that for single-story residences. As stated by the expert panel of the Manager of Penang Development Corporation (R6), this preference can be attributed to a confluence of factors, including the efficient utilization of space, economic considerations, and localized preferences that hinge on specific geographic and market dynamics. In accordance with the expert panel, including the Director of Valuation and Property Services Department, Seberang Jaya Branch (R4), these contrasting trends emphasize the impact of regional and market-specific dynamics on housing demand, highlighting the nuanced nature of the real estate landscape.

The property market near KHTP and BKIP is thriving and poised for growth. As reported by the expert panel of the Director of Valuation and Property Services Department, Seberang Jaya Branch (R4), this positive outlook results from a combination of factors: its strategic location near industrial hubs, sustained economic expansion, ongoing infrastructure improvements, increasing job opportunities, and modern housing options. These factors make the area attractive to both real estate investors and homebuyers. Additionally, property values have seen substantial appreciation, making it a lucrative investment opportunity. It is important to note that the high-tech park’s economic development significantly influences property values by attracting tech companies and investors, increasing demand for local houses.

Furthermore, referring to the expert panel from the property developer, the Director of Oriental Kedah (R7), it is essential to recognize that housing preferences are inherently localized and can evolve over time. These preferences are strongly shaped by the interplay of local market conditions and individual lifestyle choices, ultimately influencing the demand for specific types of houses in a given area. Developers, having knowledge of these factors, take them into careful consideration when planning and constructing houses, aligning their designs with the unique needs and preferences of their target market.

5.2. Relationship Between Property Price, Foreign Investment, and Macroeconomic Variables

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of variables. KHTP has lower average property prices than BKIP for both single-story and double-story houses. The house price index also reflects this trend, with KHTP showing a slightly lower mean compared to BKIP. Generally, property prices in Kulim are more affordable than in Batu Kawan. As mentioned by the expert panel, including the Director and a representative of the Valuation and Property Services Department, Kulim Branch (R2 and R3), single-story houses, being more cost-effective than double-story homes, may be particularly attractive to workers in KHTP who seek medium- to lower-cost housing options.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

Despite this affordability, KHTP experiences a significantly higher overhang for single-story houses compared to BKIP, indicating lower demand in the area. The overhang for double-story houses in KHTP is also higher than in BKIP, suggesting a potential mismatch between supply and demand. Since double-story houses are generally more expensive, they may appeal to a narrower market segment. If buyers in KHTP are more price-sensitive or prefer single-story homes, the demand for double-story properties remains weaker, leading to an oversupply. In terms of sub-sales, KHTP records higher activity for single-story houses than BKIP, whereas the trend reverses for double-story houses, with BKIP experiencing a greater number of sub-sales. According to the expert panel of the Manager of Penang Development Corporation (R6), a high sub-sale rate can indicate strong market interest or demand in a particular area. Additionally, it may reflect speculative activity, where investors purchase properties with the intention of reselling them for profit.

KHTP also attracts significantly higher levels of foreign direct investment (FDI) compared to BKIP, driven by its sectoral focus and well-established infrastructure. As stated by the expert panel of the Director of Malaysian Investment Development Authority (R1), as a hub for high-tech industries such as electronics and IT, KHTP appeals to investors seeking opportunities in these advanced sectors. Furthermore, the industrial park may benefit from government policies and incentives designed to support high-tech industries and foreign investment, further reinforcing its attractiveness as an investment destination.

The Breusch–Godfrey (BG) test was conducted to test the heteroscedasticity between FDI and housing prices. Based on Table 4 below, the overall explanatory power of the model, evaluated using either F-tests or Chi-square tests, is found to be insignificant. Furthermore, the calculated p-values exceed reasonable thresholds. Therefore, there is no evidence to suggest the presence of heteroscedasticity according to the BG test, indicating that the error term does not significantly change in response to the values of the independent variables.

Table 4.

Breusch–Godfrey (BG) test for Kulim Hi-Tech Park (KHTP) and Batu Kawan Industrial Park (BKIP).

Additionally, the Durbin–Watson (DW) test was conducted to determine the presence of serial correlation in the dataset. Serial correlation can bias the estimated variances of regression coefficients, thereby compromising the reliability of hypothesis testing. A rule of thumb is that DW test statistic values in the range of 1.5 to 2.5 are relatively normal. Lewis-Beck et al. (2004) suggests that values under 1 or more than 3 are a definite cause for concern.

A DW statistic value of 2.0 for both Model 1 and 2 for Kulim and Batu Kawan in Table 5 indicates no autocorrelation, suggesting that the model is unaffected by serial correlation issues. However, the DW test values of 2.1 for both Model 3 and 4 in Kulim and Batu Kawan suggest slight positive autocorrelation in the residuals, although it is not severe.

Table 5.

Durbin–Watson (DW) test for Kulim Hi-Tech Park (KHTP) and Batu Kawan Industrial Park (BKIP).

Additionally, the endogeneity and exogeneity tests were conducted to detect whether there are endogenous regressors in the regression model. If endogenous regressors are present in the model (p-value is less than 0.05), this indicates that the independent variables are correlated with the error term, causing the estimated coefficients to be biased and the standard errors to be incorrect.

Table 6(a) and (b) show that the independent variables are strictly exogenous (p-value is greater than 0.05). Exogenous variables are independent variables that are not influenced by other variables within the model. This also indicates that, on average, the error term does not have any systematic effect on the dependent variable.

Table 6.

(a) Endogeneity and exogeneity test for Kulim Hi-Tech Park. (b) Endogeneity and exogeneity test for Batu Kawan Industrial Park.

Building on the Muellbauer and Murphy (1997) model, this study examines the relationship between house prices, property demand, and FDI in KHTP and BKIP, considering the influence of other key macroeconomic variables. This study utilizes two different measures of property price as dependent variables, namely house price and house price index. This study also used two measures of property demand, which are property sub-sale and property overhang. The analysis results using the two dependent variables are presented in Table 7 and Table 8. Based on the two dependent variables, only the case where house price is the dependent variable shows interesting results, whereas most of the independent variables show significant results, whether using property sub-sale or property overhang as the measurement for property demand.

Table 7.

The relationship between house prices and property demand, foreign investment, and macroeconomic variables for single-story and double-story houses in Kulim Hi-Tech Park and Batu Kawan Industrial Park.

Table 8.

The relationship between house price index, property demand, foreign investment, and macroeconomic variables for single-story and double-story houses in Kulim Hi-Tech Park and Batu Kawan Industrial Park.

6. Discussions and Policy Recommendations

Table 7 and Table 8 show the mixed results of the relationship between property demand (either sub-sale or property overhang) and property prices for both single- and double-story houses. For instance, a negative and significant coefficient, as shown in Models 3 and 16, indicates that an increase in property overhang is associated with a decrease in house prices. This may occur when property overhang leads to oversupply, causing property developers or sellers to reduce prices. It could also reflect market perceptions of oversupply leading to buyer caution and lower willingness to pay. Conversely, a positive and significant coefficient, as shown in Model 7, contradicts the theory. This indicates that an increase in property overhang is associated with an increase in house prices. In accordance with the expert panel, including the Director of the Valuation and Property Services Department, Seberang Jaya Branch (R4), this could occur if the presence of property overhang is interpreted by the market as a signal of future scarcity or as an indicator of preferred housing attributes that are still in demand despite the overhang.

On the other hand, a positive and significant coefficient, as shown in Models 1, 2, and 10, indicates that an increase in property sub-sales is associated with an increase in house prices. Higher demand for properties can drive up prices as buyers compete for limited available units, leading to higher offers in competitive markets. Additionally, in line with the expert panel, including the Director of the Valuation and Property Services Department, Kulim Branch (R2), government intervention through affordable housing policies can impact property prices by either slowing down price increases or changing demand patterns.

The further effect of housing policy is evident in the coefficient results, where the negative relationship between housing policy and property prices in the above tables suggests that the implementation of an affordable housing policy is associated with a decrease in house prices. This means that the implementation of affordable housing programs, schemes, and incentives tends to lower house prices compared to periods without such programs. Based on the findings, the housing policy has proven effective in lowering the price of single-story homes in Batu Kawan, as shown in Table 7, where housing prices are notably high. Therefore, increasing the supply of more affordable housing options is expected to have a significant influence on single-story home prices in this area. In contrast, Kulim recorded lower prices for double-story houses, as shown in Models 2 and 4, as a result of the implementation of a housing policy aimed at reducing housing prices.

Affordable housing programs in Malaysia typically aim to increase the supply of housing that is affordable to middle- and lower-income households. For instance, as of 30 September 2023, a total of 274,258 units of affordable homes were completed or were under construction, representing 54.8 percent of the targeted 500,000 units under the 12th Malaysia Plan (12MP). This increase in supply, if not matched by a proportional increase in demand, can put downward pressure on house prices. However, according to the expert panels of the Manager of Penang Development Corporation (R6) and the Director of Oriental Kedah (R7), in some cases, the implementation of an affordable housing program may signal to the market that there is an intention to stabilize or reduce housing costs. This expectation could influence buyers and sellers, leading to lower price levels.

There is a positive and significant relationship between property prices, foreign investment (FDI), and gross domestic product (GDP) for most of the results. From the aspect of FDI, this relationship is evident in the increasing foreign investment in Kulim Hi-Tech Park (KHTP) and Batu Kawan Industrial Park (BKIP), which, in turn, attracts more property development to these areas. Over the long term, this surge in development contributes to a rise in property prices. In other words, the presence of foreign investor-owned companies in industrial areas increases the demand for properties, particularly single- and double-story houses. This effect is further increased by the rise in economic activities in industrial areas, resulting from greater employment opportunities, which, in turn, raises households’ labor income and industrial production, ultimately boosting the demand for housing. For example, the launch of Industrial Zone Phase 4 in Kulim Hi-Tech has spurred a remarkable 69% surge in double-story housing transactions within the surrounding area over the past two decades, accumulating a total transaction value of RM341.16 million (NAPIC, 2022). According to the Valuation and Property Services Department (JPPH), the average property prices continue to rise annually, whereby between 2010 and 2020, the average property price in Malaysia increased by 45 percent. These fluctuations in property prices have a significant impact on the economic conditions of the population and society in KHTP and BKIP. This result is consistent with a study done by Chow and Xie (2016) and Liao et al. (2014), which reported that FDI significantly influences housing prices in Singapore. Likewise, Kim and Lee (2022) also found a positive relationship between FDI and house prices in South Korea from 2011 to 2016.

In addition to GDP, an increase in economic activities in KHTP and BKIP will drive the demand for property, which will increase property prices. When the GDP is increasing, it signals that a state’s economy is growing well. The expansion of KHTP and BKIP will create more job opportunities for the citizens and generate income level rises, which promote a better standard of living. According to the Department of Statistics Malaysia, as the mean salary of households in Kulim has increased by 37 percent from 2010 to 2018, the consumer spending patterns for goods and services have also increased (DOSM, 2019). In general, salary increments have increased the purchasing power on consumption. Income increases are expected to have a positive effect on property demand. This might have caused property developers near KHTP and BKIP to develop more single- and double-story properties as the demand for property increases, consequently increasing property prices. This result is consistent with a study done by Solak and Kabadayi (2016), which revealed that income level is the most critical factor in determining the demand for housing. In the same way, Bergin and Garcia-Rodriguez (2020) indicate that actual housing demand depends on income distribution. The study highlights a positive elasticity between disposable income and house prices, suggesting that an increase in income leads to an even greater rise in house prices.

There is some evidence that the relationship between property prices and inflation is negatively significant, as shown in Model 4, which contradicts the theory. Generally, inflation is a sustained increase in the general price levels, which leads to a reduction in purchasing power. Lending rates tend to go up with inflation (Cho, 2005). According to Khazanah Research Institute (2019), construction costs, including labor, materials, machinery, and equipment, have increased slightly over the past 10 years. The median land price in Kulim and Seberang Jaya Selatan (RM per sq. feet) has also risen in a decade. When the property cost increases, the financing cost will also increase, leading to a rise in the lending rate. If the interest rates increase, the cost of borrowing becomes more expensive, and the demand for lending will decline as demand for property falls. This might have caused the property prices to drop. For example, although the inflation rate in Malaysia was recorded as 3.8 percent in 2017, the highest since 2010, the market value of residential property in 2017 decreased by 12.79% between Quarter 1 and Quarter 4 (NAPIC, 2017). Furthermore, during a high-inflation period, an oversupply of residential property may also affect property prices and reduce demand. This result is consistent with a study done by Korkmaz (2019), where the housing price index in Istanbul and Izmir, Turkiye, started to decrease after 2016, while the increase in the consumer price index continued.

Following the significant findings on the relationship between property prices and property demand, FDI, and macroeconomic variables in this study, we make the following policy recommendations:

- First, attracting more FDI to Malaysia is imperative. Increased FDI introduces new businesses and expands existing ones, generating more job opportunities for local workers and the potential for higher wages and leading to improved income levels for local workers. As employment and incomes increase, the demand for property also rises.

- Second, balancing the supply of affordable housing is imperative to prevent housing market imbalances through affordable housing policy. To increase the supply of affordable housing and manage rising property prices, several strategies and mechanisms can be implemented, including offering tax incentives to developers who build affordable housing and converting unsold or overhanging properties into affordable housing.

- Third, in order to address the need for affordable housing programs effectively, it is essential to strengthen affordable housing policies and implement robust monitoring and evaluation frameworks. These mechanisms can help mitigate the upward pressure on housing prices caused by industrial growth and ensure that rising demand does not compromise housing accessibility for local residents.

7. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

As foreign direct investment (FDI) increases, property prices will also rise. Although this increase in property prices might create difficulties for buyers looking to purchase property, it simultaneously enhances the value of property investments. This study examines the relationship between FDI and the residential property price in Kulim Hi-Tech Park and Batu Kawan Industrial Park. The analyses in Table 7 and Table 8 show that FDI has a positive and significant relationship with property prices; as FDI increases, property prices are likely to rise as well due to an upsurge in property demand. Consequently, this increased demand can elevate property prices, making it challenging for many, especially those with lower incomes, to afford homes. Therefore, the disparities in the housing market in Malaysia can be addressed through effective affordable housing policies by balancing the supply of affordable housing.

The study related to housing price and FDI is not only an important focus in Malaysia but also in other countries. In recent years, house prices have surged in numerous OECD and Asian countries, along with increased foreign direct investment inflows; hence, this reduces affordability. Nevertheless, changes in the FDI inflow patterns to some countries could negatively affect their property markets. Thus, the diversification strategy for foreign investments by investing in other continents might help mitigate potential risks.

Despite that, this study has several limitations. First, the data employed in this study are compiled annually, with findings derived from models suitable for this frequency, and this dataset extends only to 2022. Should the data be subject to updates and become accessible in the future, they may be utilized to augment the study. Second, this study does not focus on other market factors, such as socio-economic factors, demographic variables, credit policy, tax regulation, and welfare outcomes of the lower-income groups due to the limited availability of data within the specified period at the district level. Once the data become available and accessible, future research could explore this area further. Third, this study does not incorporate other relevant explanatory variables, such as the real estate price volatility index and green building policies or ESG-compliant land use planning, which could provide deeper insights due to the unavailability of data at the district level. However, by addressing these considerations, future research can explore these new dimensions and significantly contribute to the existing literature. Fourth, this study does not consider the role of modern technologies in foreign investments, the digitization of the real estate sector, the impact of proptech platforms on FDI, and the risk of investing in technology and innovation within the real estate sector due to the limited availability of data at the district level. It is suggested that future research includes these factors to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Author Contributions

N.H.I.: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Data collection; Writing—original draft. M.Z.A.K.: Conceptualization; Methodology; Formal analysis; Visualization; Writing—review and editing. H.X.H.B. (corresponding author): Funding acquisition; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Institut Penilaian Negara (INSPEN), Valuation and Property Services Department, Ministry of Finance Malaysia under NAPREC Research Grant 2023/2024 (NAPREC 07/2023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are owned by the fund provider and are available upon request. Data sources are provided in the paper to access data.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to Rosliza Ramli from the Valuation and Property Services Department (JPPH) and Mohd Rushdan Mohd Ghazali from the Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA) for providing data and invaluable support throughout the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BKIP | Batu Kawan Industrial Park |

| FDI | Foreign direct investment |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| KHTP | Kulim Hi-Tech Park |

References

- Ab Majid, R., Said, R., & Chong, J. T. S. (2017). Assessment of bubbles in the Malaysian housing market. Journal of the Malaysian Institute of Planners, 15(3), 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accetturo, A., Lamorgese, A. R., Mocetti, S., & Pellegrino, D. (2021). Housing supply elasticity and growth: Evidence from Italian cities. Journal of Economic Geography, 21(3), 367–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T., & Malawat, T. (2010). Foreign direct investment in real estate in India: Challenges and implications. The IUP Law Review, 1(1), 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, J. B. (2008). Determinants of foreign direct investment in Malaysia. Journal of Policy Modeling, 30(1), 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J., Javorcik, B., & Mattoo, A. (2006). The productivity effects of services liberalization: Evidence from the Czech Republic. World Bank Working Paper. Available online: https://www.etsg.org/ETSG2006/papers/Javorcik.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Arnott, R. (1987). Economic theory and housing. In E. S. Mills (Ed.), Handbook of regional and urban economics (Vol. 2, pp. 959–988). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum-Snow, N., & Han, L. (2024). The microgeography of housing supply. Journal of Political Economy, 132(6), 1793–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergin, A., & Garcia-Rodriguez, A. (2020). Regional demographics and structural housing demand at a county Level. Research Series. Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI). Available online: https://www.esri.ie/system/files/publications/RS111.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Bourassa, S. C., Hoesli, M., & Sun, J. (2006). A simple alternative house price index method. Journal of Housing Economics, 15(1), 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calza, A., Monacelli, T., & Stracca, L. (2013). Housing finance and monetary policy. Journal of the European Economic Association, 11, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozza, D. R., Hendershott, P. H., Mack, C., & Mayer, C. J. (2002). Determinants of real property price dynamics. National Bureau of Economic Research, United States. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w9262 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Case, K. E., Glaeser, E. L., & Parker, J. A. (2000). Real estate and the macroeconomy. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, 119–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D. (2005). Interest rate, inflation, and housing price: With an emphasis on chonsei price in Korea. NBER Working Paper Series No. 11054. NBER. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w11054 (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Chow, H. K., & Xie, T. (2016). Are house prices driven by capital flows? Evidence from Singapore. Journal of International Commerce, Economics and Policy, 7(01), 1650006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S., & Panday, P. K. (2018). Policy impact study: A conceptual framework. In Strengthening local governance in Bangladesh. Public administration, governance and globalization (Vol. 8, pp. 17–34). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dart, C. (2023). Simplification of the UK Tax System, is it a good idea? Available online: https://www.alliotts.com/articles/simplification-of-the-uk-tax-system-is-it-a-good-idea/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM). (2019). Household income and basic amenities report Kedah. DOSM. [Google Scholar]

- De Wit, I., & Van Dijk, R. (2003). The global determinants of direct office real estate return. Journal of Real Estate Finance & Economics, 26(1), 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPasquale, D., & Wheaton, W. C. (1992). The markets for real estate assets and space: A conceptual framework. Real Estate Economics, 20(2), 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, J. B. (2004). Absorptive capacity and the effects of foreign direct investment and equity foreign portfolio investment on economic growth. European Economic Review, 48(2), 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englund, P., & Ioannides, Y. M. (1997). House price dynamics: An international empirical perspective. Journal of Housing Economics, 6(2), 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G., Ong, S. E., & Koh, H. C. (2006). Determinants of property price: A decision tree approach. Urban Studies, 43(12), 2301–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeson, C., & Abdul Muin, I. M. (2015, November 12). An analysis of the factors affecting house prices in Malaysia—An econometric approach. Conference Proceedings of Social Sciences Postgraduate International Seminar (SSPIS), School of Social Sciences, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia. [Google Scholar]

- Golub, S. S. (2009). Openness to foreign direct investment in services: An international comparative analysis. The World Economy, 32(8), 1245–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenaway, D., Sousa, N., & Wakelin, K. (2004). Do domestic firms learn to export from multinationals? European Journal of Political Economy, 20(4), 1027–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R., & Arku, G. (2006). Housing and economic development: The evolution of an idea since 1945. Habitat International, 30(4), 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, Z. A. (2010). Property price and affordability in housing in Malaysia. Akademika, 78, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hii, J. H. W., Latif, L. A., & Nasir, M. A. (1999, July 29–30). Lead-lag relationship between housing and gross domestic product in Sarawak. The International Real Estate Society Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, E. C. M., & Chan, K. K. K. (2014). Foreign direct investment in China’s real estate market. Habitat International, 43, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InterNations. (2013). Malaysian property market: Economic issues. Available online: www.internations.org/kuala-lumpur-expats/forum/malaysian-property-market-1-economicissues-809849 (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Ismail, N., & Nayan, S. (2021). A dynamic relationship between consumer confidence and residential property price: Empirical evidence for Malaysia. International Journal of Property Sciences, 11(1), 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L. (2014). Recent trends on housing affordability research: Where are we up to? Cities Working Paper Series, WP No.5/2014. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2555439 (accessed on 15 December 2024). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Joghee, S., Alzoubi, H. M., & Dubey, A. R. (2020). Decisions effectiveness of FDI investment biases at real estate industry: Empirical evidence from Dubai Smart City Projects. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research, 9, 3499–3503. [Google Scholar]

- Khazanah Research Institute. (2019). Rethinking housing: Between state, market and society: A special report for the formulation of the national housing policy (2018–2025), Malaysia. Khazanah Research Institute. Available online: https://www.krinstitute.org/Publications-@-Rethinking_Housing-;_Between_State,_Market_and_Society.aspx (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Kim, J., & Lee, S. (2022). Foreign direct investment and housing prices: Evidence from South Korea. International Economic Journal, 36(2), 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, Ö. (2019). The relationship between housing prices and inflation rate in Turkey. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 13(3), 427–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, W., & Liu, P. (2015). Inflation and house prices: Theory and evidence from 35 major cities in China. International Real Estate Review, 18(1), 217–240. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. (2016). Getting serious about affordable housing. Canadian center for Policy Alternatives BC Office, Vancouver. Available online: https://policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/BC%20Office/2016/05/CCPA-BC-Affordable-Housing.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Lewis-Beck, M. S., Bryman, A., & Liao, T. F. (2004). Durbin-Watson Statistic. In The SAGE encyclopedia of social science research methods (p. 291). Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W. C., Zhao, D., Lim, L. P., & Wong, G. K. M. (2014). Foreign liquidity to real estate market: Ripple effect and housing price dynamics. Urban Studies, 52(1), 138–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C. S., Almeida, S. J., & Wei, H. S. (2017). Affordable housing: Challenges and the way forward. Bank Negara Malaysia Quarterly Bulletin. Available online: http://www.bnm.gov.my (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Liu, Y., Gao, H., Cai, J., Lu, Y., & Fan, Z. (2022). Urbanization path, housing price and land finance: International experience and China’s facts. Land Use Policy, 113, 105866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. (2008). Foreign direct investment and technology spillovers: Theory and evidence. Journal of Development Economics 85, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaysia Investment Development Authority (MIDA). (2015). Malaysia investment performance report 2015. MIDA. Available online: https://www.mida.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/20160301100315_MIPR2015-2.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Malaysia Investment Development Authority (MIDA). (2016). Malaysia investment performance report 2016. MIDA. Available online: https://www.mida.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/20171101140914_MIDA-FINAL20MIPR2016.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Malaysia Investment Development Authority (MIDA). (2017). Malaysia investment performance report 2017. MIDA. Available online: https://www.mida.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/20190315122020_MIDA20IPR2017.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Malaysia Investment Development Authority (MIDA). (2018). Malaysia investment performance report 2018. MIDA. Available online: https://www.mida.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/20190315105335_MIDA20IPR202018.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Malaysia Investment Development Authority (MIDA). (2019). Malaysia investment performance report 2019. MIDA. Available online: https://www.mida.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/20200421151258_MIDA20IPR20201920fullbook_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Malaysia Investment Development Authority (MIDA). (2020). Malaysia investment performance report 2020. MIDA. Available online: https://www.mida.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/MIDA-IPR-2020_FINAL_March4.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Malaysia Investment Development Authority (MIDA). (2021). Malaysia investment performance report 2021. MIDA. Available online: https://www.mida.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/MIDA-IPR-2021-1.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Malaysia Investment Development Authority (MIDA). (2022). Malaysia investment performance report 2022. MIDA. Available online: https://www.mida.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/MIPR-2022.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Malpezzi, S. (1999). A simple error correction model of house prices. Journal of Housing Economics, 8(1), 27–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A. (1890). Principles of Economics. MacMillan & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Masron, T. A., & Md Nor, A. H. S. (2016). Foreign investment in real estate and housing affordability. Jurnal Ekonomi Malaysia, 50(1), 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaljek, D. (2005). Free movement of capital, the real estate market and tourism: A blessing or a curse for Croatia on its way to the European Union? In K. Ott (Ed.), Croatian accession to the European Union: Facing the challenges of negotiations (pp. 185–228). Institute of Public Finance. [Google Scholar]

- Muellbauer, J., & Murphy, A. (1997). Booms and busts in the UK Housing Market. Economic Journal, 107(445), 1701–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Property Information Center (NAPIC). (2017). Property market report 2017. NAPIC. [Google Scholar]

- National Property Information Center (NAPIC). (2022). Data visualization: Property status. NAPIC. Available online: https://napic2.jpph.gov.my/en/data-visualization?category=17&id=293 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Nguyen, T. N. (2011). Foreign direct investment in real estate projects and macroeconomic instability. ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 28(1), 74–96. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41317194 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Noman, S. M. S., & Khudri, M. M. (2015). The effects of monetary and fiscal policies on economic growth in Bangladesh. ELK Asia Pacific Journal of Finance and Risk Management, 6(3), 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Olanrewaju, A., & Tan, S. Y. (2018). An exploration into design criteria for affordable housing in Malaysia. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology, 16(3), 360–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, T. Z. (2013). Factors affecting the price of housing in Malaysia. Journal of Emerging Issues in Economics, Finance and Banking, 1(5), 414–442. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2011). Housing and the economy: Policies for renovation. In Economic policy reforms 2011: Growing for growth. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Osmadi, A., Kamal, E. M., Hassan, H., & Fattah, H. A. (2015). Exploring the Elements of Housing Price in Malaysia. Asian Social Science, 11(24), 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otrok, C., & Terrones, M. (2004). The global property price boom. IMF World Economic Outlook. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, J. (2017). Foreign direct investment in the UK real estate market. Pacific Rim Property Research Journal, 23(3), 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, E. S., Rajan, R. G., & Subramanian, A. (2007). Foreign capital and economic growth. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 38(1), 153–209. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R. D. (1993). What makes democracy work? National Civic Review, 82(2), 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Regency Invest. (2024). New build property price growth more than double older homes—UK property investment news. Available online: https://www.regencyinvest.co.uk/property-investment-news/new-build-property-price-growth-more-than-double-older-homes?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Richards, A. (2005). Big fish in small ponds: The trading behavior and price impact of foreign investors in Asian emerging equity markets. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 40(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, M., & Baum, A. (2016). Determinants of foreign direct real estate investment in selected MENA countries. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 34(2), 116–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinani, E., & Meyer, K. E. (2004). Spillovers of technology transfer from FDI: The case of Estonia. Journal of Comparative Economics, 32(3), 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solak, A. O., & Kabadayi, B. (2016). An econometric analysis of housing demand in Turkey. Advances in Management and Applied Economics, 6, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Soon, A., & Tan, C. (2020). An analysis on housing affordability in Malaysian housing markets and the home buyers’ preference. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 13(3), 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanyan, V., Poghosyan, T., & Bibolov, A. (2010). Property price determinants in selected countries of the former Soviet Union. IMF Working Paper 2010-104. IMF. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2010/wp10104.pdf#:~:text=As%20determinants%20of%20house%20prices,%20they%20employ%20real%20per%20capita (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Sutton, G. D. (2002). Explaining changes in house prices. BIS Quarterly Review. Bank for International Settlements. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/r_qt0209f.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Sutton, G. D., Mihaljek, D., & Subelyte, A. (2017). Interest rates and property prices in the United States and around the world. BIS Working Papers, No 665. Bank for International and Settlements. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/work665.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Tan, C., Mohamed, A., Habibullah, M. S., & Chin, L. (2020). The impacts of monetary and fiscal policies on economic growth in Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. South Asian Journal of Macroeconomics and Public Finance, 9(1), 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrones, M., & Otrok, C. (2004). The global house price boom. In International Monetary Fund (Ed.), World economic outlook (pp. 77–136). International Monetary Fund. . Available online: https://www.imf.org/~/media/Websites/IMF/imported-flagship-issues/external/pubs/ft/weo/2004/02/pdf/_chapter2pdf.ashx (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Tsatsaronis, K., & Zhu, H. (2014). What drives housing price dynamics: Cross-country evidence. BIS Quarterly Review March. Bank for International and Settlements. [Google Scholar]

- Tumbarello, P., & Wang, S. (2010). What drives property prices in Australia? A cross-country approach. IMF Working Paper Series WP/10/291. IMF. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2010/wp10291.pdf#:~:text=This%20paper%20analyzes%20the%20factors%20driving%20house%20prices%20in%20Australia (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- United Nations Trade & Development (UNCTAD). (2004). World investment report 2004. UNCTAD. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2004_en.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- United Nations Trade & Development (UNCTAD). (2015). World investment report 2015. UNCTAD. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2015_en.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- United Nations Trade & Development (UNCTAD). (2016). World investment report 2016. UNCTAD. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2016_en.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Valadez, R. M. (2015). The housing bubble and the GDP: A correlation perspective. Journal of Case Research in Business and Economics, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J. C. (2015). Measuring monetary policy’s effect on house prices. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRBSF) Economic Letter. Available online: https://www.frbsf.org/wp-content/uploads/el2015-28.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Xu, T. (2017). The relationship between interest rates, income, GDP growth and house prices. Research in Economics and Management, 2, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J. B. H., & Ng, X. H. (2018). Housing affordability in Malaysia: Perception, price range, influencing factors and policies. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 11(3), 476–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y. C., Hui Nee, A. Y., & Senadjki, A. (2019). The nexus between housing glut, economic growth, housing affordability and property price in Malaysia. Journal of the Malaysian Institute of Planners, 17(1), 267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Zietz, J., Zietz, E. N., & Sirmans, G. S. (2008). Determinants of property prices: A quantile regression approach. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 37, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).