Determinants of Financial Performance in Advertising and Marketing Companies: Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cross-Country Analysis

2.2. Determinants of Financial Performance

2.3. Advertising and Marketing Companies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling

3.2. Variables

- -

- Liquidity ratio—Current Ratio;

- -

- Turnover ratio—Debt to Equity;

- -

- Solvency ratio—Total Asset Turnover.

3.3. Equation

4. Results

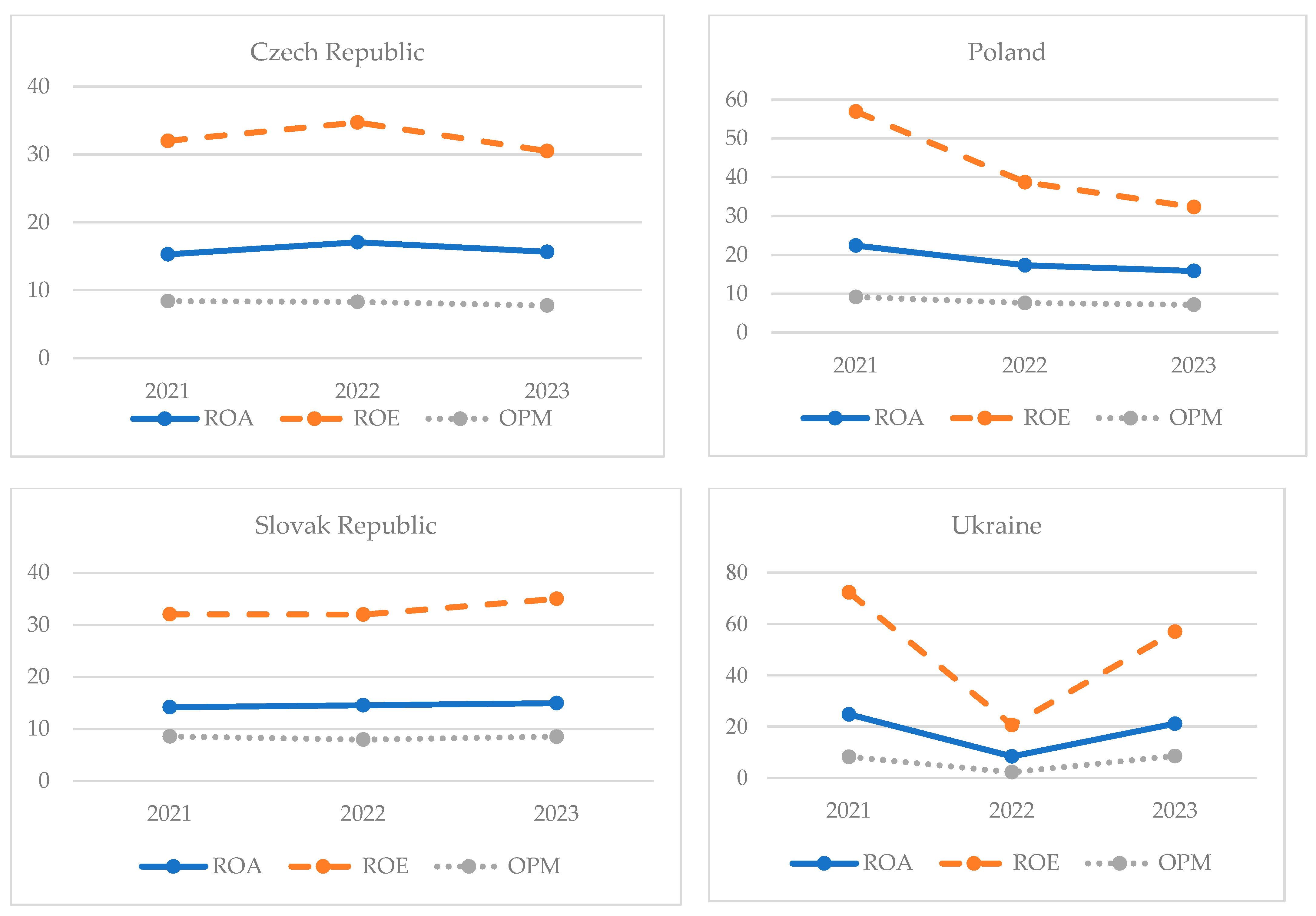

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

- -

- Poland is the leader in average ROA values (mean = 18.5);

- -

- Ukraine is the leader in average ROE values (mean = 50.0), although it demonstrates the maximum volatility, from min −862.3 to max 840.61, compared to other countries;

- -

- The Slovak Republic is the leader in average OPM values (mean = 8.3), i.e., USD 8.3 of operating profit is generated from every dollar of sales before interest and taxes.

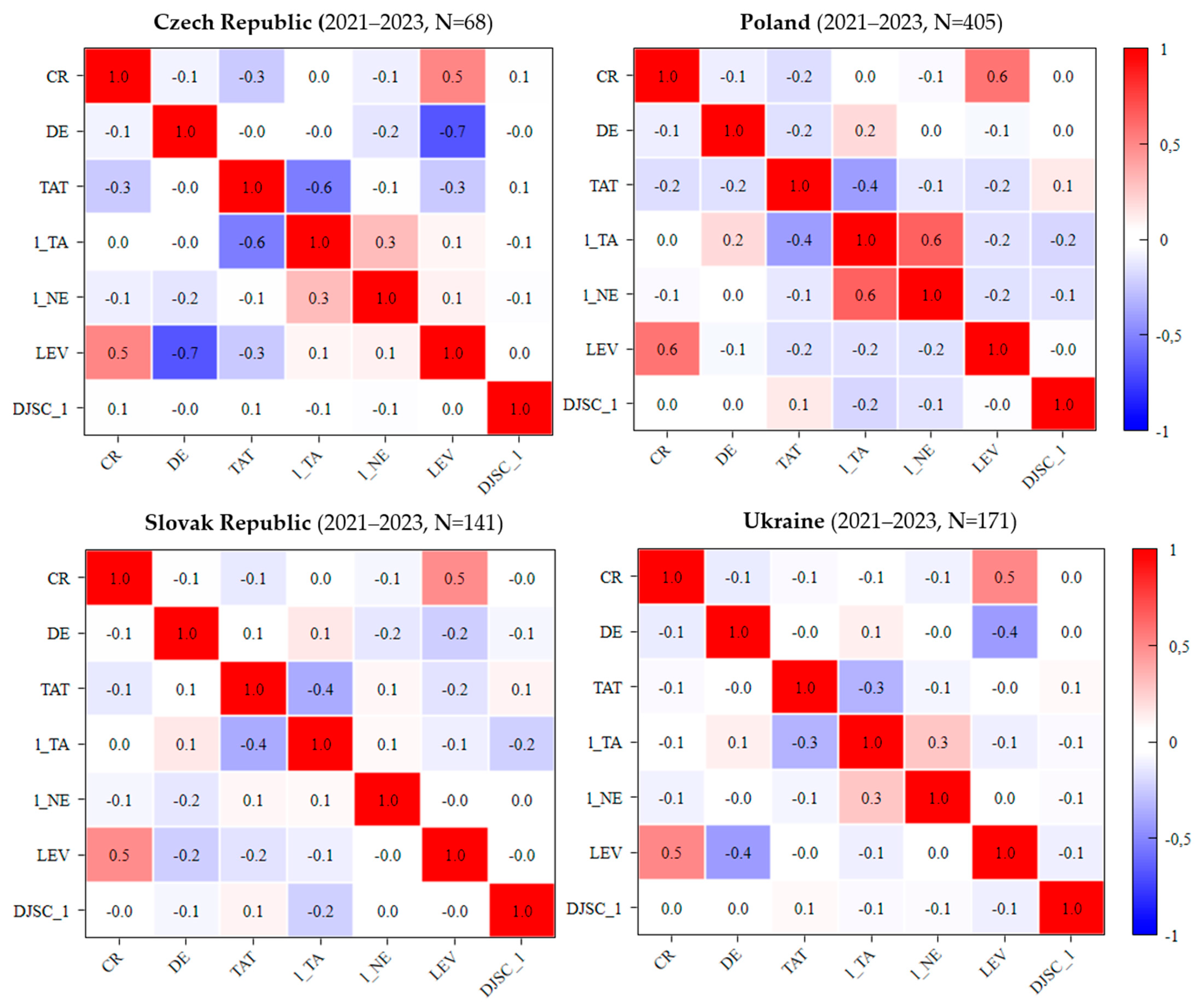

4.2. Multicollinearity Assessment

4.3. Model Selection

4.4. Empirical Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CEE | Central and Eastern Europe |

| CCA | Cross-country analysis |

| ROA | Return on Assets |

| ROE | Return on Equity |

| OPM | Operating Profit Margin |

| CR | Current Ratio |

| DE | Debt to Equity |

| TAT | Total Asset Turnover |

| 1_TA | Logarithm of total assets |

| 1_NE | Logarithm of the number of employees |

| LEV | Leverage |

| DJSC_1 | Dummy variable for joint-stock company |

| WLS | Weighted Least Squares |

| REM | Random Effect Model |

| FEM | Fixed Effect Model |

| LAD | Least Absolute Deviations |

| IDX | Indonesia Stock Exchange |

References

- Abraham, R., Chaarani, H. E., & Tao, Z. (2024). The Impact of audit oversight quality on the financial performance of U.S. firms: A Subjective assessment. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(4), 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikawa, Y., Inoue, K., & Saito, T. (2019). Corporate Governance, employment, and Financial Performance of Japanese Firms: A Cross-Country Analysis. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S., & Srivastava, A. (2016). Working capital management and firm performance in emerging economies: Evidence from india. Management and Labour Studies, 41(2), 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinal, L. B. (2001). Technological innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: The use of organizational control in managing research and development. Organization Science, 12(1), 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., Ngniatedema, T., & Li, S. (2018). A cross-country comparison of green initiatives, green performance and financial performance. Management Decision, 56(5), 1008–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, Y., Kim, K., & Combs, J. (2013). Advertising agency operating efficiency. Journal of Marketing Communications, 22(1), 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślik, A., Michałek, A., Michałek, J., & Mycielski, J. (2015). Determinants of export performance: Comparison of Central European and Baltic firms. Finance a Uver-czech Journal of Economics and Finance, 64(3), 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, P. M., Ewing, M. T., & Cooper, H. B. (2020). Balancing creativity and organisational performance in an advertising agency network: A case study. Journal of Marketing Communications, 27(8), 840–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delen, D., Kuzey, C., & Uyar, A. (2013). Measuring firm performance using financial ratios: A decision tree approach. Expert Systems With Applications, 40(10), 3970–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dencic-Mihajlov, K. (2015). Profitability during the financial crisis: Evidence from the regulated capital market in Serbia. SEEJE, 12(1), 7–33. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Fernandez, M., Bornay-Barrachina, M., & Lopez-Cabrales, A. (2015). Innovation and firm performance: The role of human resource management practices. Evidence-based HRM a Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 3(1), 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrah, O., Rahman, A. a. A., Jamil, S. A., & Ghafeer, N. A. (2016). Exploring the Relationship between Liquidity Ratios and Indicators of Financial Performance: An Analytical Study on Food Industrial Companies Listed in Amman Bursa. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 6(2), 435–441. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, G. C., Zhang, Y., Hu, Q., & Cheng, H. (2018). Performance of China’s advertising agencies: A time series cross-sectional analysis. Asia Pacific Business Review, 24(5), 656–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharios, R., Awad, A. B., Khalaf, B. A., & Seissian, L. A. (2024). The impact of board gender diversity on European firms’ performance: The moderating role of liquidity. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(8), 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, V. M. (2012). Leverage and corporate performance: International evidence. International Review of Economics & Finance, 25, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantono, H. (2018). The effect of current ratio, debt to equity ratio, toward return on assets (case study on consumer goods company). Accountability, 7(02), 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, I., Kobeissi, N., Liu, L., & Wang, H. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance: The mediating role of productivity. Journal of Business Ethics, 149(3), 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, S. D., Gulzar, S., Ghafoor, Z., & Naz, I. (2020). Sensitivity of firm size measures to practices of corporate finance: Evidence from BRICS. Future Business Journal, 6(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irman, M., & Purwati, A. A. (2020). Analysis on the influence of current ratio, debt to equity ratio and total asset turnover toward return on assets on the otomotive and component company that has been registered in Indonesia Stock Exchange within 2011–2017. International Journal of Economics Development Research (IJEDR), 1(1), 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jati, D., Setiawan, H., Purnomo, S. D., Muntahanah, S., Zuhaena, F., & Arinastuti, A. (2023). Determinants of profitability: Evidence from construction companies listed on indonesian securities market. JAMPE (Journal of Asset Management and Public Economy), 2(2), 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliani, D. I., Karyatun, S., & Digdowiseiso, K. (2023). The effect of current ratio, total asset turnover and debt to equity ratio on the financial performance of manufacturing companies listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange for the 2016–2020 period. Jurnal Syntax Admiration, 4(4), 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangari, R., Farid, F., & Elgharib, H. M. (1992). Financial Performance Analysis for construction industry. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 118(2), 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiymaz, H., Haque, S., & Choudhury, A. A. (2024). Working capital management and firm performance: A comparative analysis of developed and emerging economies. Borsa Istanbul Review, 24(3), 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehenchuk, S., Chyzhevska, L., Meluchová, J., Zdyrko, N., & Voskalo, V. (2023). Determinants of agricultural companies’ financial performance: The experience of Poland, Slovakia and Ukraine. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 20(1), 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehenchuk, S., Serpeninova, Y., Zavalii, T., Juhaszova, Z., & Kordošová, A. (2022). The impact of financial performance on the profitability of advertising agencies in the Slovak Republic. Strategic Management, 28(1), 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, E., Quach, T. N., & Thaichon, P. (2018). Enhancing client-agency relationship quality in the advertising industry—An application of project management. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 34(2), 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, E., Thaichon, P., Quach, S., & Lobo, A. (2017). The role of creativity and project management in enhancing service quality of Advertising Agencies: A Qualitative approach. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 26(1), 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. L., & Hwang, N. R. (2011). Effects of firm size, financial leverage and R&D expenditures on firm earnings: An analysis using quantile regression approach. Abacus, 47(2), 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listiyono, A., Lau, E. A., & Dewi, C. K. (2022). Pengaruh current ratio, debt to equity ratio, total assets turnover terhadap pertumbuhan laba rumah sakit yang terdaftar di bursa efek Indonesia pada masa COVID 19. Exchall Economic Challenge, 4(1), 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Valeiras, E., Gomez-Conde, J., & Fernandez-Rodriguez, T. (2016). Firm size and financial performance: Intermediate effects of indebtedness. Agribusiness, 32(4), 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J. (2019). Advertising industry evolution: Agency creativity, fluid teams and diversity. An exploratory investigation. Journal of Marketing Management, 35(9–10), 845–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madushanka, K. H. I., & Jathurika, M. (2018). The Impact of Liquidity Ratios on Profitability (With special reference to Listed Manufacturing Companies in Sri Lanka). International Research Journal of Advanced Engineering and Science, 3(4), 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, S. B., Corvino, A., & Rigolini, A. (2012). Board diversity and structure: What implications for investments in innovation? Empirical evidence from Italian context. Corporate Ownership and Control, 10(1), 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazanec, J. (2023). Capital structure and corporate performance: An empirical analysis from central Europe. Mathematics, 11(9), 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassim, I., & Benraïss, B. (2024). Capital structure and financial performance of Moroccan Agricultural Small-and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Moderating effects of Government subsidies. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(7), 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. T. C., Le, A. T. H., & Van Nguyen, C. (2024). The impact of liquidity and corporate efficiency on profitability. Emerging Science Journal, 8(1), 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyilasy, G., Canniford, R., & Kreshel, P. J. (2013). Ad agency professionals’ mental models of advertising creativity. European Journal of Marketing, 47(10), 1691–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, H., Kilgour, M., Koslow, S., & Sasser, S. (2017). Drivers of creativity within advertising agencies. Journal of Advertising Research, 58(2), 202–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odhiambo, A., Koske, N., & Limo, P. (2022). Debt-Equity ratio, CEO power and financial performance of listed companies at the Nairobi Securities Exchange, Kenya. European Journal of Business Management and Research, 7(2), 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patin, J., Rahman, M., & Mustafa, M. (2020). Impact of total asset turnover ratios on equity returns: Dynamic panel data analyses. Journal of Accounting Business and Management (JABM), 27(2), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachman, S., Karyatun, S., & Digdowiseiso, K. (2023). The effect of current ratio, debt to equity ratio, debt to asset ratio, and total asset turnover on the financial performance of property and real estate companies listed in the IDX for the 2016–2020 period. Jurnal Syntax Admiration, 4(2), 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramnoher, L., & Seetah, K. (2020). The link between profitability and financial leverage, evidence from a small island economy. Asian Journal of Finance & Accounting, 12(1), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnaningtyas, H., & Nurbaeti, N. (2023). The effect of current ratio and total assets turnover on stock prices and return on assets as intervening variables. At-Tadbir Jurnal Ilmiah Manajemen, 7(1), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizqullah, R., & Siregar, J. K. (2021). The determinant of financial performance based on good corporate governance and company size in the basic industrial and chemical sectors 2015–2019. In First international conference on science, technology, engineering and industrial revolution (ICSTEIR 2020). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabati, A.-A. A., Ali, A. A. A., Allahham, M. I., Hussein, A. A., Alheet, A. F., & Mohammad, A. S. (2024). The impact of digital marketing on the performance of SMEs: An analytical study in light of modern digital transformations. Sustainability, 16(19), 8667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siminica, M., Ionașcu, C., & Sichigea, M. (2018). Corporate social performance versus financial performance of the romanian firms. Prague Economic Papers, 28(1), 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supardi, H., Suratno, H. S. H., & Suyanto, S. (2018). Pengaruh current ratio, debt to asset ratio, total asset turnover dan inflasi terhadap return on asset. JIAFE (Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi Fakultas Ekonomi), 2(2), 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, R. Z., Herceg, I. V., Hanák, R., Hortovanyi, L., Romanová, A., Mocan, M., & Djuričin, D. (2020). Industry 4.0 implementation in B2B companies: Cross-country empirical evidence on digital transformation in the CEE region. Sustainability, 12(22), 9538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuraisingam, R. (2015). The Effects of liquidity management on firm profitability: Evidence from Sri Lankan listed companies. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 6(5), 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, V. H., Van Nguyen, D., Tran, M. M., & Duong, K. D. (2023). Capital structure and profitability of listed firms in a transition market, Does debt maturity matter? Montenegrin Journal of Economics, 19(1), 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniamikogbo, E., Wogu, I. a. P., Aigienohuwa, O. O., Misra, S., & Kaushik, M. (2023). Corporate social responsibility and the financial performance of oil and gas entrepreneurial marketing firms. In futuristic technology perspectives on entrepreneurship and sustainable innovation (pp. 52–73). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Nordenflycht, A. (2010). Firm Size and Industry Structure Under Human Capital Intensity: Insights from the Evolution of the Global Advertising Industry. Organization Science, 22(1), 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S., & Graves, S. (1997). The corporate social performance—Financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrad, N. L., & Omari, N. R. A. (2015). The impact of turnover ratios on Jordanian services sectors’ performance. Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing, 11(2), 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weill, L. (2007). Leverage and corporate performance: Does institutional environment matter? Small Business Economics, 30(3), 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek-Kosmala, M., Błach, J., & Gorzeń-Mitka, I. (2021). Does capital structure drive profitability in the energy sector? Energies, 14(16), 4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q., Neill, M. S., & Schauster, E. (2018). Paid, earned, shared and owned media from the perspective of advertising and public relations agencies: Comparing China and the United States. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(2), 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavalii, T., Lehenchuk, S., Poyda-Nosyk, N., Ishchenko, Y., & Hrabchuk, O. (2024). Nexus between risk factors and financial performance: The case of Ukrainian advertising and marketing companies. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 21(4), 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Calculation Method | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | ||

| Return on Assets | Profit before tax/Total assets × 100% | ROA |

| Return on Equity | Profit before tax/Shareholder funds × 100% | ROE |

| Operating Profit Margin | EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes)/Sales × 100% | OPM |

| Independent Variables | ||

| Current Ratio | Current assets/Current liabilities | CR |

| Debt to Equity | Total liabilities/Total equity | DE |

| Total Asset Turnover | Sales/Total assets | TAT |

| Control Variables | ||

| Company Size (1) | Logarithm of total assets | 1_TA |

| Company Size (2) | Logarithm of number of employees | 1_NE |

| Leverage | Total debt/Total assets | LEV |

| Dummy Variable for Joint-Stock Company | 0 for joint-stock company, 1 for non-joint-stock company | DJSC_1 |

| Variables | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CZ | PL | SK | UK | CZ | PL | SK | UK | CZ | PL | SK | UK | |

| ROA | 16.0 | 18.5 | 14.6 | 18.0 | −14.9 | −79.6 | −36.5 | −200.6 | 75.99 | 389.36 | 77.7 | 547.60 |

| ROE | 32.4 | 42.6 | 33.0 | 50.0 | −82.4 | −781.6 | −770.4 | −862.3 | 116.57 | 737.09 | 171.7 | 840.61 |

| OPM | 8.2 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 6.3 | −25.8 | −94.8 | −53.3 | −100.0 | 63.32 | 82.53 | 90.8 | 91.22 |

| CR | 3.6 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 25.06 | 37.97 | 38.4 | 90.95 |

| DE | 1.4 | 4.1 | 6.6 | 4.9 | 0.0 | −37.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 22.09 | 302.32 | 563.3 | 161.88 |

| TAT | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.74 | 28.58 | 20.0 | 25.59 |

| 1_TA | 7.5 | 7.6 | 7.2 | 6.6 | 3.8 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 1.7 | 10.42 | 13.77 | 10.5 | 12.97 |

| 1_NE | 2.57 | 2.87 | 2.01 | 3.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.69 | 5.06 | 7.26 | 4.44 | 6.50 |

| LEV | 58.1 | 48.5 | 42.4 | 43.1 | 4.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 99.71 | 99.72 | 97.8 | 99.88 |

| DJSC_1 | 0.85 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Czech Republic | Poland | |||||

| ROA | ROE | OPM | ROA | ROE | OPM | |

| p-value | 5.04085 × 10−25 | 1.26437 × 10−18 | 4.34511 × 10−27 | 3.93484 × 10−40 | 1.2328 × 10−16 | 1.78502 × 10−55 |

| REM/FEM | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| WLS | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Slovak Republic | Ukraine | |||||

| ROA | ROE | OPM | ROA | ROE | OPM | |

| p-value | 1.71764 × 10−37 | 5.24513 × 10−5 | 1.77955 × 10−28 | 2.02385 × 10−30 | 7.62612 × 10−19 | 1.86687 × 10−24 |

| REM/FEM | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| WLS | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Czech Republic | Poland | |||||

| ROA | ROE | OPM | ROA | ROE | OPM | |

| p-value | 0.141 | 0.185 | 0.039 | 6.88317 × 10−10 | 0.0007 | 4.62999 × 10−14 |

| REM | + | + | – | – | – | – |

| FEM | – | – | + | + | + | + |

| Slovak Republic | Ukraine | |||||

| ROA | ROE | OPM | ROA | ROE | OPM | |

| p-value | 0.0013 | 2.16466 × 10−11 | 1.34824 × 10−7 | 5.24264 × 10−8 | 3.64252 × 10−7 | 7.35781 × 10−10 |

| REM | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| FEM | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Czech Republic | Poland | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | ROE | OPM | ROA | ROE | OPM | |

| p-value | 0.288 | 0.728 | 0.166 | 7.02787 × 10−5 | 4.12124 × 10−5 | 0.001 |

| Slovak Republic | Ukraine | |||||

| ROA | ROE | OPM | ROA | ROE | OPM | |

| p-value | 0.153 | 4.92128 × 10−11 | 0.789 | 0.139 | 0.667 | 0.274 |

| REM/FEM * | LAD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akaike Information Criterion | Schwarz Information Criterion | Hannan–Quinn Information Criterion | Akaike Information Criterion | Schwarz Information Criterion | Hannan–Quinn Information Criterion | |

| M1CROA | 1643 | 1669 | 1653 | 1597 | 1623 | 1608 |

| M2CROE | 1946 | 1972 | 1956 | 1881 | 1908 | 1892 |

| M3COPM | 1182 | 1428 | 1282 | 1358 | 1384 | 1368 |

| M1PROA | 10,709 | 12,806 | 11,498 | 10,194 | 10,235 | 10,209 |

| M2PROE | 13,453 | 15,550 | 14,242 | 12,394 | 12,435 | 12,410 |

| M3POPM | 8507 | 10,604 | 9296 | 7412 | 7453 | 7427 |

| M1SROA | 3183 | 3777 | 3418 | 3488 | 3520 | 3500 |

| M2SROE | 4638 | 5233 | 4873 | 4405 | 4437 | 4418 |

| M3SOPM | 3045 | 3640 | 3280 | 3142 | 3175 | 3155 |

| M1UROA | 4977 | 5728 | 5271 | 4740 | 4774 | 4754 |

| M2UROE | 6106 | 6857 | 6400 | 5849 | 5883 | 5862 |

| M3UOPM | 4203 | 4953 | 4497 | 4058 | 4092 | 4071 |

| Const | CR | DE | TAT | 1_TA | 1_NE | LEV | DJSC_1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | ||||||||

| M1CROA | 0.212 | 0.672 | 0.056 * | 0.0005 *** | 0.685 | 0.171 | 0.407 | 0.880 |

| M2CROE | 0.005 *** | 0.582 | 0.026 ** | 0.052 * | 0.320 | 0.051 * | 0.0009 *** | 0.814 |

| M3COPM | 0.091 * | 0.680 | 0.776 | 0.002 *** | 0.319 | 0.065 * | 0.658 | 0.729 |

| M1PRO | 0.013 ** | 0.007 *** | 1.17 × 10−6 *** | 1.49 × 10−11 *** | 0.359 | 0.985 | 9.25 × 10−9 *** | 0.133 |

| M2PROE | 0.093 * | 2.63 × 10−6 *** | 1.18 × 10−7 *** | 7.39 × 10−9 *** | 0.012 ** | 0.101 | 1.12 × 10−8 *** | 0.106 |

| M3POPM | 5.17 × 10−8 *** | 8.27 × 10−11 *** | 1.47 × 10−59 *** | 0.848 | 0.956 | 0.505 | 0.002 *** | 0.366 |

| M1SROA | 0.080 * | 0.816 | 0.748 | 0.010 *** | 0.337 | 0.103 | 7.67 × 10−6 *** | 0.004 *** |

| M2SROE | 0.324 | 0.464 | 0.994 | 0.010 *** | 0.074 * | 0.023 ** | 0.216 | 0.003 *** |

| M3SOPM | 0.008 *** | 0.097 * | 0.836 | 0.463 | 0.0005 *** | 0.044 ** | 0.061 * | 0.158 |

| M1UROA | 0.073 * | 0.67 | 0.229 | 0.0013 *** | 0.693 | 0.093 * | 0.0003 *** | 0.0008 *** |

| M2UROE | 0.049 ** | 0.419 | 0.619 | 0.019 ** | 0.282 | 0.182 | 0.002 *** | 0.135 |

| M3UOPM | 0.435 | 0.549 | 0.684 | 0.002 *** | 0.014 ** | 0.016 ** | 0.009 *** | 0.289 |

| Country | Quantity | Period | Sector | CR | DE | TAT | 1_TA | 1_NE | LEV | DJSC_1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Czech Republic | 68 | 2021–2023 | Advertising and market research | Insign. | Sign. * Neg. | Sign. *** Pos. | Insign. | Insign. | Insign. | Insign. |

| Poland | 405 | Sign. *** Pos. | Sign. *** Pos. | Sign. *** Pos. | Insign. | Insign. | Sign. *** Pos. | Insign. | ||

| Slovak Republic | 141 | Insign. | Insign. | Sign. *** Pos. | Insign. | Insign. | Sign. *** Pos. | Sign. *** Pos. | ||

| Ukraine | 171 | Insign. | Insign. | Sign. *** Pos. | Insign. | Sign. * Neg. | Sign. *** Pos. | Sign. *** Pos. |

| Country | Quantity | Period | Sector | CR | DE | TAT | 1_TA | 1_NE | LEV | DJSC_1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Czech Republic | 68 | 2021–2023 | Advertising and market research | Insign. | Sign. ** Neg. | Sign. ** Pos. | Insign. | Sign. ** Neg. | Sign. *** Neg. | Insign. |

| Poland | 405 | Sign. *** Pos. | Sign. *** Pos. | Sign. *** Pos. | Sign. ** Neg. | Insign. | Sign. *** Neg. | Insign. | ||

| Slovak Republic | 141 | Insign. | Insign. | Sign. *** Pos. | Sign. * Pos. | Sign. ** Neg. | Insign. | Sign. *** Pos. | ||

| Ukraine | 171 | Insign. | Insign. | Sign. ** Pos. | Insign. | Insign. | Sign. *** Neg. | Insign. |

| Country | Quantity | Period | Sector | CR | DE | TAT | 1_TA | 1_NE | LEV | DJSC_1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Czech Republic | 68 | 2021–2023 | Advertising and market research | Insign. | Insign. | Sign. *** Neg. | Insign. | Sign. * Neg. | Insign. | Insign. |

| Poland | 405 | Sign. *** Pos. | Sign. *** Pos. | Insign. | Insign. | Insign. | Sign. *** Pos. | Insign. | ||

| Slovak Republic | 141 | Sign. * Pos. | Insign. | Insign. | Sign. *** Pos. | Sign. ** Neg. | Sign. * Pos. | Insign. | ||

| Ukraine | 171 | Insign. | Insign. | Sign. *** Neg. | Sign. ** Pos. | Sign. ** Neg. | Sign. *** Pos. | Insign. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zavalii, T.; Lehenchuk, S.; Chyzhevska, L.; Hrabchuk, I. Determinants of Financial Performance in Advertising and Marketing Companies: Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18030141

Zavalii T, Lehenchuk S, Chyzhevska L, Hrabchuk I. Determinants of Financial Performance in Advertising and Marketing Companies: Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(3):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18030141

Chicago/Turabian StyleZavalii, Tetiana, Serhii Lehenchuk, Lyudmyla Chyzhevska, and Iryna Hrabchuk. 2025. "Determinants of Financial Performance in Advertising and Marketing Companies: Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 3: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18030141

APA StyleZavalii, T., Lehenchuk, S., Chyzhevska, L., & Hrabchuk, I. (2025). Determinants of Financial Performance in Advertising and Marketing Companies: Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(3), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18030141